Abstract

Problem being addressed In a medically under-served rural Canadian community where overburdened family physicians provide most of the cae for patients with mental illness and substance use problems, providing access to timely and effective help for all citizens is a challenge. The care burden of unmet mental health needs is experienced throughout the larger community by diverse community service providers.

Supporting a shared understanding of the needs and challenges, and ensuring effective connection and clear communication between diverse disciplines in primary care, community services and the formal mental health system requires models of service organisation and delivery that go beyond traditional clinical roles.

In cancer care a navigator model has previously been used to address information and service gaps and improve patient experience. We wished to evaluate whether a community-supported navigator model could help solve some of the challenges for clients and service providers in our community, while at the same time allowing data collection that offers a clearer understanding of actual service needs.

Pre-programme activities Community members formed an interdisciplinary community steering committee which met monthly for two years to develop and adapt a service and collaborative research model, generate support, secure ethical approval and raise funds.

Programme description The navigator service was embedded in a local family service organisation, the steering committee met monthly, and along with the researchers met regularly with programme staff and provided support, oversight and development of ethical data collection.

Navigators provided low barrier access, comprehensive assessment, collaborative service planning, and linkage and referral facilitation for any individual or family who requested assistance with a mental health or substance use concern. Navigators also serve as an information resource for any community service provider or family physician needing to assist a client, and collected data on local service needs.

Conclusions Analysis of quantitative administrative data, consented research data, and qualitative interview and survey data demonstrated that this community supported navigator service model was effective in improving service access, assessment and linkage for citizens with mental health and addictions concerns, and connecting a range of community services into a more effective network of care. Connecting unattached clients with a primary care provider and supporting needs assessment and service planning for patients of local family physicians were key navigator functions.

Keywords: community based participator research, mental health navigation, navigator model, primary mental health care

Problem being addressed

The rural community of Sooke, BC in Western Canada, has local access only to primary health care, and local providers are over-burdened as the population grows. In Canada, primary care is the principal resource for most people who seek help for depression, anxiety, and alcohol or other substance misuse, as well as more serious and persistent mental illnesses.1,2 Family physicians struggle to meet the demands of the increasing volume and complexity of the patients with mental health and addictions diagnosis and treatment needs they see every day. Meeting the needs of citizens with mental health and addictions problems requires a network of services that operate seamlessly across primary care, mental health services, emergency services, schools, law enforcement, and numerous community services and organisations involved in provision of health and social services.3,4

Seamless care for mental health and addiction (MHA) issues is challenging to organise, requiring co-operation across disciplines and traditionally compartmentalised silos of care.4 Family physicians are often ill-equipped and inadequately compensated to conduct the full psychosocial needs assessment necessary to help patients plan for and cope with complex MHA needs.5 If the patient's need is known, primary care providers (and other community agencies) may not have the time to maintain an updated understanding of the complex ever-changing array of services available. Many formal MHA services require a family physician's referral, but MHA clients are less likely to have an identified family physician.5 Problems in communication and connection between multiple components of the service system leave patients experiencing fragmented care and providers feeling frustrated.4,5 Geography, lack of transportation, and other barriers can prevent patients from accessing needed service.6 When planning for formal mental health services is based on past utilisation, only those patients who actually managed to receive service get counted as needing service. This utilisation-based planning environment (in contrast to planning service based on population-based needs) led to underestimation of the number of people needing help and insufficient service allocation in our community. To offer effective care, family physicians and other community service providers need support for patients with complex MHA issues. To advocate for local services we required better data on service needs and gaps in care.

The impact of these issues was experienced firsthand by local physicians and other community service providers in our region.7 Family physicians and local service providers indicated that they needed support to: (a) determine what services were available for patients with complex mental health issues, (b) assess and refer these patients for help, (c) find ways to help patients past barriers to accessing referred services, and (d) act as a communication hub between primary care, other providers and the patient, ensuring clarity of roles and responsibilities.7 The Navigator project was designed to meet these needs in our community.

Pre-programme activities

Over a two-year period, interested community members formed a steering committee to direct and guide an innovative mixed-method research project.8,9 We researched Navigator models that had been successfully used in cancer care to improve service co-ordination, integration, education and support, including assistance with barriers.6,10 The committee chose this model for the development of a service to support patients and service providers in ‘navigating’ through the maze of available mental health and addiction services.

The need for local data to inform community members and health authority service planners, coupled with the opportunity for Navigators to acquire relevant data on local service demand and gaps in care at the community level, led to the community-based action research model. Ethical approval was secured through the University of British Columbia, the Vancouver Island Health Authority, the University of Victoria, and Simon Fraser University. Funding was secured through a variety of foundation, government and health authority granting sources.

Our project combined consented research data collection on client service need with the provision of a clinical Navigator service, over a 21-month period from July 2005 to February 2007. Ongoing Navigator service and administrative data collection continued to May 2009.

Prior to the start of the Navigator service, a survey (validated courtesy of Dr N Kates, McMaster University) was mailed to 35 regional family physicians in the local health area. Eleven responses (31%) were received. Table 1 is an extract of a larger dataset that clearly demonstrates physicians’ concerns regarding information about, communication with, and availability of MHA services.5 Pre-project interviews with community service providers confirmed that they experienced similar frustrations.5

Table 1.

Physician ratings of overall MHA services in local region in 2005 (n = 11)

| Rating | Satisfaction with availability of services | Quality of services | Communication with MHA services | Availability of information about MHA services |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good to very good | 0 | 7 | 0 | 2 |

| Fair | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Poor to very poor | 8 | 3 | 6 | 7 |

All of the local Sooke physicians (excluding the principal investigator) and six nearby physicians who see patients from the Sooke region responded to the survey

Project goals

The two primary goals of the Sooke Navigator Project were to:

connect any person with mental health and/or addictions needs to timely, accessible and appropriate service

gather relevant data on local service needs in order to inform future service planning.

In order to optimise the network of existing services in meeting clients' needs, the Navigator role supported clients to engage with the network of services, and increased the efficiency of existing services by providing client needs assessment, communication, linkage and co-ordination of care.

Programme description

From July 2005 to May 2007, referrals and self-referrals were welcomed from anyone in the community, provided the client was willing to meet with a Navigator and wished to access service for mental health or substance use issues. The youth and adult Navigators were clinicians with a background in counselling, social work and psychiatric rehabilitation, and each had over five years of related experience.

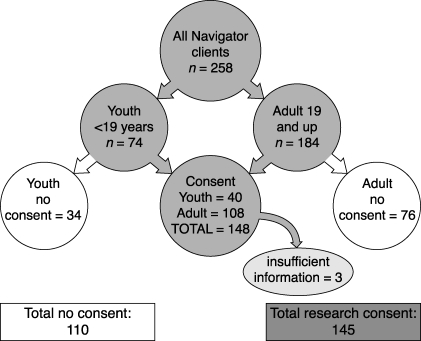

Navigators were mobile, and met with clients at a variety of appropriate locations within the community, including family physician offices, school settings, the employment centre, and their own offices. Administrative data were collected on all clients, and a more detailed research dataset was collected from the clinical files of those who gave consent (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of Navigator clients by age and choice of research consent

Age and/or sex did not affect the likelihood of Navigator clients offering research consent. When it was unclear who, within a family unit, the identified client was, we did not seek research consent. Thirty-six families worked with the youth Navigator over the course of the Navigator programme.

The key elements of the Navigator model of service facilitation were:

timely, simple access for any person: youth, adult or family; using an advanced-access service model,11 the Navigator service did not carry a waitlist, and all clients were contacted within 24–48 working hours after referral

non-judgemental respect and acceptance of clients

comprehensive, structured psychosocial assessment of needs and strengths was offered to all clients

collaborative service planning with the client and others as necessary, including identification of pre-existing barriers for clients

routine assessment of service gaps, potential barriers, and planning to ‘span’ the gaps or plan around obstacles

clear consistent communication, including a written needs assessment report controlled by the client, containing a service plan, offered to family physicians and other care providers with client consent

sharing up-to-date knowledge about MHA, available services, referral pathways and requirements with both clients and service providers

tracking referrals for individual clients

providing an informal point of connection for marginalised clients

follow-up with clients to determine reasons for successful or unsuccessful connections.

Programme evaluation

The Navigator service saw 258 discrete clients over a 21-month period. Navigators made 168 referrals to MHA services on behalf of the 145 clients who gave consent for research data acquisition and have sufficient data available for analysis. Seventy percent of these clients had been connected to referral services by the time of follow-up. Although accurate quantitative pre-Navigator baseline data for comparison were unavailable, systematic qualitative enquiry with community service providers indicated that Navigation appeared to result in more appropriate and effective referrals to existing services, and resulted in fewer clients experiencing gaps in service availability.

In this community action research model, we used multiple sources of information and iterative enquiry to evaluate and modify the service on an ongoing basis. We collected data from consented, structured client assessments, semi-structured interviews with community service providers and local physicians, client feedback forms, and regularly documented informal communications with service providers and members of the steering committee.

Review and analysis of multiple data sources determined that Navigator service improved communication between primary care physicians and community-based service providers about shared patients and availability of local services. Providing family physicians (where clients consented and when they actually had a family physician) with a brief written summary and action plan kept them informed and involved. This activity was rated as very important in interviews with local family physicians and other service providers.

Narrative data collected over the project demonstrated numerous collateral benefits from performing this action research within our community. These benefits included:

stronger connection and improved communication and understanding were experienced by the agencies who participated in the Navigator steering committee. This was evidenced by their increased capacity to work collaboratively to solve challenging problems and advocate for themselves, their agencies and their community

a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of available services and access pathways developed over time and continues to evolve

steering committee members now have an awareness of the community-based participatory action research model as a useful tool to better understand their community's needs and advocate for enhanced service

sustainability and generalisability of a pilot programme may be considered evaluative hallmarks. The Navigator project has now become an ongoing programme. The mental health and addictions Navigator model is currently under development in three other settings in BC, suggesting that the model has face validity.

Limitations of this service

A Navigator service model is predicated on the existence of a network of some services for MHA. Where there are gaps in service or lengthy delays in accessing that network, a Navigator's ability to plan with a client is challenged. Maintaining an effective Navigator programme requires sufficient community support and advocacy, clinician engagement, a commitment to local data collection, analysis and dissemination, and ongoing funding.

Conclusions

In the absence of an ideal constellation of accessible mental health and addiction services, a Navigator service model can introduce some of the responsiveness, flexibility and client support missing from the current fragmented mental health system. In a pilot project in the Sooke region, the Navigator role benefited patients, physicians and other community service providers by providing enhanced connection, information, and support and service linkage. Flexible models based on similar principles may be useful in other settings and communities.

Contributor Information

J Ellen Anderson, Sooke Community Health Initiative, Sooke BC and University of British Columbia, Department of Family Practice, Canada.

Susan C Larke, Sooke Community Health Initiative, Sooke BC, Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Health Council of Canada Health Care Renewal in Canada: accelerating change Toronto: Health Council of Canada, 2005. www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/docs/rpts/2005/Accelerating_Change_HCC_2005.pdf(accessed 10 July 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Canada. About Primary Health Care. www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/prim/about-apropos-eng.php (accessed 10 July 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vancouver Island Health Authority (VIHA) Youth and Family Addiction Services: community consultation survey Victoria BC: Esquimalt Health Unit, 2007. Unpublished report to community, Victoria, BC [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummings NA. Resolving the dilemmas in mental healthcare delivery: access, stigma, fragmentation, conflicting research, politics and more. : Cummings NA, O'Donohue WT, Cucciare MA.(eds)Universal Healthcare: readings for mental health professionals Reno, NV: Context Press, 2005, pp. 47–74 [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology Mental Health Mental Illness and Addiction: an overview of policies and programs in Canada Interim Report of The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, 2004, pp. 25–8 www.parl.gc.ca/38/1/parlbus/commbus/senate/com-e/soci-e/rep-e/report1/repintnov04vol1-e.pdf(accessed 10 July 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using Navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer 2004;104(4):848–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JEA, Larke SC. The Sooke Navigator Project: final report (2007) www.sookefamily resource.ca/Navigato-final-Report-JULY-15-2007-FINAL.pdf (accessed 10 July 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macaulay AC, Freeman WL, Gibson N, et al. Responsible Research with Communities: participatory research in primary care Leawood: National Association of Primary Care Research Group, 1998. www.napcrg.org/responsibleresearch.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stange KC, Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Publishing multimethod research. Annals of Family Medicine 2006;4:292–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farber JM, Deschamps M, Cameron R. Investigation and Assessment of the Navigator Role in Meeting the Information, Decisional and Educational Needs of Women with Breast Cancer in Canada Ottawa Canadian Breast Cancer Initiative, Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Control, Health Canada, 2002. www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ccdpc-cpcmc/cancer/publications/navigator_e.html [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray M, Bodenheimer T, Rittenhouse D, Grumbach K. Improving timely access to primary care. Case studies of the Advanced Access Model. Journal of the American Medical Association 2003;289:1042–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FUNDING

The study was supported by BC College of Family Physicians, CFPC Research and Education Foundation, the Vancouver Foundation, the University of British Columbia Department of Family Practice, the Victoria Foundation, the Ministry of Children and Family Development, The Sutherland Foundation, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, the Center for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addictions at Simon Fraser University, Vancouver Island Health Authority.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.