Traditionally, the diagnosis of schizophrenia has been viewed as having a generally unfavorable outcome.1, 2 In recent years this view has been challenged, and symptom remission is being discussed as a legitimate outcome for patients with schizophrenia. There is a growing consensus that the complete absence of symptoms should not be a requirement for remission.3–7 These definitions of remission have typically included a severity criterion as well as a time criterion, e.g., mild or no symptoms for six months or more.3–7

In 2005, an expert group of researchers, the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group,3 defined symptom remission based on the core features of schizophrenia, i.e., reality distortion, negative symptoms, and symptoms of disorganization. Although they used a focused, diagnostic based definition of remission, the authors recognized that other clinical domains and factors may also affect outcome. There have been no studies applying the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group’s remission criteria to older adults with schizophrenia. In planning for the anticipated increase in older adults with schizophrenia over the next two decades, it is critical to gauge their clinical needs as well as to understand those factors that contribute to improving remission. To address this concern, in this paper we use an adaptation of the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group’s criteria to examine the prevalence of symptomatic remission in a multiracial sample of persons aged 55 years and over with early-onset schizophrenia. We also used George’s Social Antecedent Model of Psychopathology8 as the scaffolding for the inclusion of variables that may be associated with symptomatic remission in this population.

Methodology

We recruited subjects aged 55 years and over living in the community who developed schizophrenia before the age of 45 years using a stratified sampling method in which we attempted to interview approximately half the subjects from outpatient clinics and day programs, and the other half from supported community residences in New York City. The latter consisted of sites with varying degrees of on-site supervision. Inclusion was based on a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder that was conducted by clinical agency staff (generally psychiatrists) and by a lifetime illness review adapted from Jeste and associates.9 For inclusion in the study respondents were required to have one or more of the following: (a) symptoms such as social withdrawal, loss of interest in school or work, deterioration in hygiene and grooming, unusual behaviors, outbursts of anger prior to age 45 years; (b) evidence of hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking or behavior prior to age 45 years; (c) hospitalization for schizophrenia prior to age 45 years; and (d) treatment for schizophrenia prior to age 45 years.

Subjects were excluded if they had medical conditions or a history of trauma, seizures, dementia, head injury with unconsciousness of 30 minutes or more, mental retardation, substance abuse, or evidence of bipolar illness that could better account for the subject’s psychotic symptoms prior to age 45 years. Persons with cognitive impairment too severe to complete the questionnaire were excluded from the study, i.e., defined as scores of <5 on the Mental Status Questionnaire.10 This is a 10-item screening examination for cognitive dysfunction that assesses orientation, autobiographical memory, general fund of knowledge, and concentration. According to Zarit and coauthors, 11 scores of 5 to 10 and 0–4 indicate no/mild and moderate/severe cognitive impairment, respectively.

Subjects were offered $75 for completing the 2½-hour interview. The rejection rate was 7%. The monetary incentive of $75 probably increased the response rate in this sample and accounted for the low rejection rate. The final sample consisted of 198 persons. Among these, 39% were living independently in the community and 61% in supported community residences. The mean age was 61.5 years and 49% were female; 57% were Caucasians, 35% were African Americans, 7% were Latinos, and 2% were in other categories. Median income for the group was $7000 – $12,999.

The study was approved by the institutional review board at SUNY Downstate Medical Center and each participant gave written informed consent.

Defining Remission

We established criteria for symptomatic remission using an adaptation of the criteria established by the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group.3 Subjects had to score 3 or below on eight symptom domains derived from the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS)12 and to have no history of hospitalization within the previous year. The latter is a slight modification from the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group criteria in which symptoms had to be stable for six months. Because our data were cross-sectional we could not assess symptom stability more accurately. The PANSS domains used in this study were P1 (delusions), P2 (conceptual disorganization), P3 (hallucinatory behavior), N1 (blunted affect), N4 (passive/apathetic social withdrawal), N6 (lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation), G5 (mannerisms and posturing), and G9 (unusual thought content). The sample was dichotomized into persons who met criteria for remission and those who did not.

Instruments

In order to examine factors that might be associated with remission, we used an adaptation of George’s Social Antecedent Model of Psychopathology8 so as to rationally select variables that had been found previously to be associated with better symptom outcomes. The model, which was developed for geriatric populations, includes six stages of risk factors: Demographic; Early Events and Achievements; Later Events and Achievements; Social Integration and Support; Vulnerability Factors; and Provoking Agents and Coping Strategies. The variables used for each of these categories are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bivariate Comparison of Remission and Non-Remission Groups on Variables in Model

| Remission N=96 |

Non-Remission N=100 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | t/χ2 | df | p | ||||

| Mean/ Percent |

SD | Mean/ Percent |

SD | ||||

| Demographic Factors | |||||||

| Age (mean) | 62.0 | 5.7 | 61.0 | 5.4 | 1.25 | 191 | 0.213 |

| Female (%) | 46 | ----- | 50 | ----- | 0.09 | 1 | 0.771 |

| Caucasian (%) | 60 | ----- | 52 | ----- | 2.21 | 1 | 0.138 |

| Non-Supported | 51 | ------ | 27 | ------ | 13.95 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Housing (%) | |||||||

|

Lifetime Events and Achievements |

|||||||

| Education (mean) | 12.2 | 3.3 | 13.5 | 11.8 | −1.05 | 188 | 0.293 |

|

§Lifetime Trauma (mean) |

2.8 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 4.4 | −2.41 | 173* | 0.017 |

|

Social Integration and Support |

|||||||

|

§Total Network Size (mean) |

14.3 | 3.1 | 19.5 | 6.0 | −7.66 | 151* | 0.001 |

|

†Proportion of Intimate Contacts (mean) |

0.3 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 5.21 | 179* | 0.001 |

|

†Psychiatric Services (mean) |

11.8 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 2.01 | 194 | 0.045 |

| Vulnerability Factors | |||||||

| Physical Illness (mean) | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.5 | −0.24 | 194 | 0.809 |

| §CES-D(mean) | 11.1 | 8.8 | 14.4 | 10.7 | −2.39 | 190 | 0.018 |

| †IADL (mean) | 23.0 | 3.3 | 21.4 | 4.3 | 2.86 | 185* | 0.005 |

| †QLI (mean) | 22.6 | 4.8 | 20.7 | 5.6 | 2.61 | 187* | 0.010 |

| †DRS (mean) | 131.0 | 10.7 | 124.3 | 14.3 | 3.69 | 183* | 0.001 |

| §Side Effects (mean) | 5.7 | 4.0 | 9.4 | 9.0 | −3.69 | 137* | 0.001 |

| Provoking Agents | |||||||

|

†Financial Strain (mean) |

7.7 | 3.0 | 6.8 | 3.3 | 2.19 | 194 | 0.030 |

| Coping Strategies | |||||||

| Psychotropic Medication (%) |

87 | ------ | 85 | ------ | 1.44 | 1 | 0.230 |

|

†Coping by Acceptance (mean) |

3.6 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 3.63 | 157* | 0.001 |

higher scores indicate better functioning

lower scores indicate better functioning

CES-D: left for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

QLI: Quality of Life Index

DRS: Dementia Rating Scale

Unequal variance t-test was used because the Levene test was significant.

Based on our literature review of remission in schizophrenia,5–7, 13–15 we were able to identify 18 independent variables to insert into the model. The independent variables were derived from the following scales: the Quality of Life Index (QLI),16 a multidimensional self-appraisal instrument that assesses both satisfaction and importance of 32 likert-type items; Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D);17 Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL), in which lower scores indicate more impairment;18 a “Physical Illness” score that represented the sum of 7 healthcare items and 13 illness categories derived from the Multilevel Assessment Inventory and the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale;18 the Network Analysis Profile,19 was used to derive two variables: the total number of social network contacts and the mean proportion of persons who were considered intimates; the Financial Strain Scale,20 in which lower scores denote more strain; “Acceptance of the Situation” Subscale, a 4-item subscale derived by principal components analysis of the Pearlin Coping Scale20 (higher scores indicate greater use of this coping style); the Dementia Rating Scale,21 which assesses five areas of cognitive functioning: attention, initiation and perseveration, construction, conceptualization, and memory (higher scores indicate better functioning); Lifetime Trauma Scale,22 a 12-item scale based on the number of times persons experience trauma or victimization such as crime victim, assault, physical or sexual abuse, incarceration; Medication Side Effects Scale based on neurological and autonomic side effects; and the mean frequency of mental health treatment that was derived from the mean sum of the frequencies of receiving services for medication treatment, group therapy, individual talk or behavioral therapy, psychiatric day treatment, and family treatment, then multiplied by 100 (e.g., score of 100 = average of once per week; score of 25 = average of once per month; 6 = average of 4 times per year). The data gathered from the study group did not include a breakdown of the type of psychotropic medications the individuals were taking. As noted in table 1, nearly nine of ten respondents were taking a psychotropic medication (almost always an antipsychotic agent), so there was not sufficient variation in the use of medication to be included as a variable.

The internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) scores of the scales were: QLI (0.97), CES-D (0.88), PANSS positive scale (0.83), PANSS negative scales (0.78), Acute Stressors Scale (0.88), Financial Strain Scale (0.79), IADL scale (0.77), Dementia Rating Scale (0.89), Lifetime Trauma Scale (0.71), Medication Side Effects (0.63), and Acceptance of the Situation Subscale (0.61). All scales attained recommended alphas of 0.60 or higher.23

Interviewers were trained with the assistance of audio- and videotapes. Interviewers were psychology students or persons with backgrounds in mental health care and they were generally matched to respondents from similar ethnic backgrounds. Interviewers were periodically monitored using audiotapes of their interviews. The intra-class correlations (ICC) ranged from 0.79 to 0.99 on the various scales (n=7 to 10 ratings). Raters had a mean of 99% and 94% agreement with expert ratings (author CIC) on the dichotomous items of the physical illness score and the Network Analysis Profile scores, respectively.

Data Analysis

Initially, we examined the 18 independent variables in our model associated with remission using bivariate analysis and t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. For t-tests, the unequal variance t-test was used when findings of the Levine test were significant. We then conducted logistic regression analysis to determine the independent effects of these variables and to examine the utility of the overall model. Using the methods suggested by Hsieh,24 with an alpha of 0.05, a power level of 80%, an event proportion value of 0.49, and an average correlation coefficient of 0.20 between the independent variables, a sample size of 198 allowed us to detect odds ratios of 1.46 or higher ( i.e., a medium effect). There was no evidence of collinearity among the variables entered into the logistic regression analysis.

Results

We found that 58% of the sample met the PANSS criteria of ≤3 on the 8 PANSS domains and 83% had no history of hospitalization in the past year. Overall, 49 % of the sample met our criteria for remission based on symptom remission and no hospitalizations in the past year. The remission rate for those <65years was 47 % (n=144), and for those ≥65years it was 53 % (n=49). The differences between the 2 groups was not significant (χ2 =0.50; df=1; p=0.48).

Using bivariate analysis (Table 1), we found that remission was associated with 12 of 18 variables in the model: higher QLI, lower CESD, higher IADL, lower lifetime trauma scores, higher DRS scores, fewer medication side effects, more mental health services, increased ability to cope by acceptance of the situation, independent living, less financial strain, fewer network contacts, and a higher mean proportion of intimates among their social contacts. Using a more conservative cut-off in the bivariate analysis of 0.01 would reduce the number of significant variables from 12 to 8. We also further examined the relationship between components of network size and remission, and found that remission positively correlated with the size of the kin network (r = 0.17, df = 194, p = 0.02), number of formal contacts (r = 0.19, df = 194, p = 0.008), but inversely with non-kin network size (r = −0.55, df = 194, p <0.001).

In logistic regression (Table 2), only four of the 12 variables retained significance: fewer network contacts, greater proportion of intimates, fewer lifetime traumatic events, and higher DRS scores. The theoretical model attained statistical significance (χ2 = 88.22, df = 18, p <0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of Remission and Non-Remission Groups on Variables in Model Using Logistic Regression Analysis

| Variable | Odds | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | Lower | Upper | ||

| Demographic Factors | ||||

| Age | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.14 | 0.207 |

| Female | 1.30 | 0.56 | 3.03 | 0.542 |

| Caucasian | 1.74 | 0.74 | 4.10 | 0.204 |

| Non-Supported Housing | 0.71 | 0.30 | 1.65 | 0.420 |

| Events and Achievements | ||||

| Education | 0.94 | 0.83 | 1.07 | 0.343 |

| Lifetime Trauma | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.95 | 0.006 |

| Social Integration and Support | ||||

| Total Network Size | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.000 |

| Proportion of Intimate Contacts | 9.83 | 1.44 | 67.31 | 0.020 |

| Psychiatric Services | 1.04 | 0.99 | 1.81 | 0.126 |

| Vulnerability Factors | ||||

| Physical Illness | 1.03 | 0.75 | 1.42 | 0.870 |

| Center for Epidemiological | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.04 | 0.620 |

| Studies Depression Scale | ||||

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

1.08 | 0.95 | 1.22 | 0.253 |

| Quality of Life Index | 0.98 | 0.88 | 1.08 | 0.653 |

| Dementia Rating Scale | 1.04 | 1.003 | 1.09 | 0.037 |

| Side Effects | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.06 | 0.489 |

| Provoking Agents | ||||

| Financial Strain | 1.00 | 0.87 | 1.15 | 0.979 |

| Coping Strategies | ||||

| Psychotropic Medication | 0.37 | 0.08 | 1.64 | 0.189 |

| Coping by Acceptance | 1.55 | 0.94 | 2.55 | 0.087 |

Note: ORs >1 & ORs <1 indicate independent variable is higher or lower in remission group, respectively.

Model: χ2 = 88.22, df =18, P <0.001

Discussion

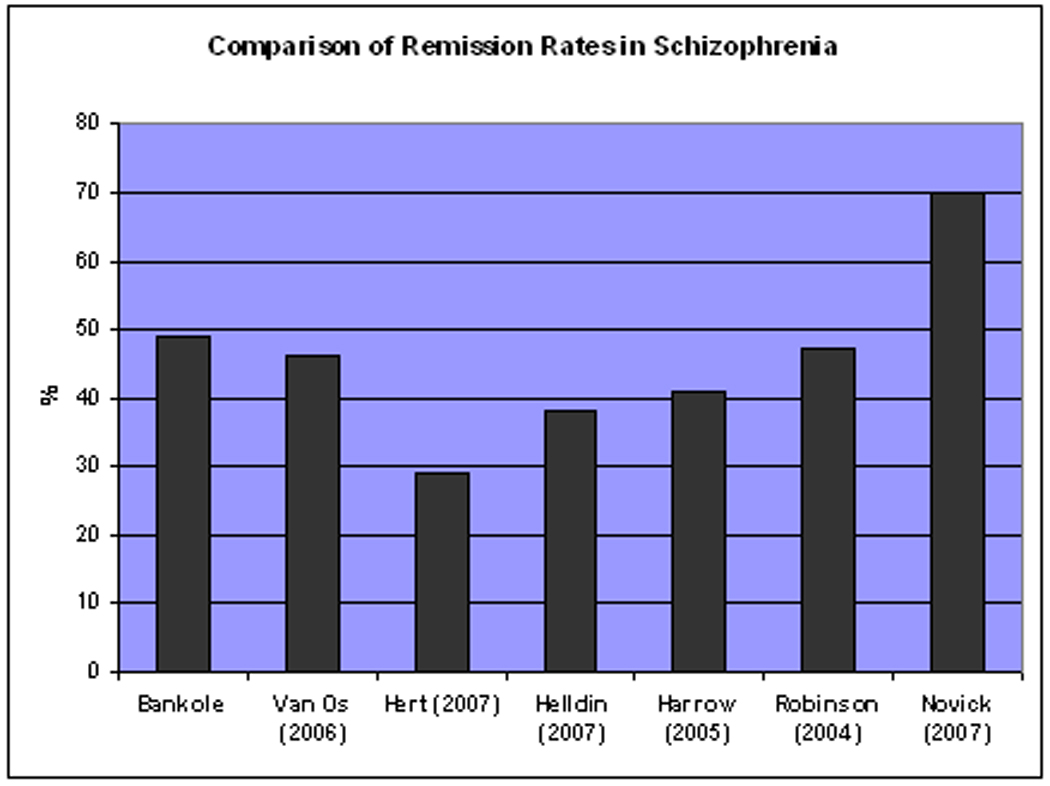

Our findings suggest that symptomatic remission is an attainable goal in many older adults with schizophrenia. The remission rate of 49% in our study was within the range of rates reported for younger persons;5, 6, 25, 26, 33–35 the latter ranged from 29% to 70% (Figure 1). Novick et al34 found higher rates of symptomatic remission (70%) in a longitudinal multi-country European study of 701 individuals with schizophrenia who had never been treated prior to the study. Leucht and associates35 used the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group’s criteria on several clinical trials and found symptomatic remission rates varied from 29% to 50% (last observation carried forward) or 31% to 59% (completers only).

Figure 1.

Our results are also consistent with earlier catamnestic studies of previously hospitalized patients in which about half showed symptom improvement (mostly positive symptoms) on long-term follow-up into later life.15, 27–31 Our findings add to the accumulating evidence that the prevailing view of the course of schizophrenia-- one of early deterioration followed by a lifetime of chronicity and residual symptoms32—requires a more nuanced picture, especially in later life.

Importantly, remission is not recovery, and remission is not necessarily a stable state. The fact that 15% of persons in our study who had attained symptom remission reported being hospitalized in the previous year suggests some flux in symptoms. In a younger sample, van Os and coauthors5 found 35% moved out of remission and 31% moved into remission over a period of several years. Several writers have noted that “recovery” must include symptom, functioning, and hospitalization criteria.4, 33 Thus, one study by Auslander and colleagues7 of middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia based on symptom and functional criteria found only 8% met such criteria. Thus, remission can be viewed as part of a continuum that may lead to recovery in a smaller proportion of older persons with schizophrenia.

Although the model used in this study attained statistical significance, its utility is not entirely clear. In bivariate analysis, 12 of the 18 variables attained significance, and each of the six model categories had at least one significant variable. However, when the variables were entered concurrently in the logistic regression analysis, only 4 variables retained significance, and only three of the categories contained significant variables. The odds ratios for three of the four significant variables were very modest. We are uncertain as to why only 4 of the 18 variables that had been cited in the literature as being associated with outcome in schizophrenia attained significance in our study. This may reflect the greater age of our sample or our use of a more comprehensive multivariate model that took into account the interaction of the predictor variables. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that while the model has some utility—e.g., even in its present form it achieved statistical significance--it will most likely require further modifications.

With respect to specific variables in our model, we found that higher scores on the Dementia Rating Scale were associated with remission. This was consistent with studies of younger adults in which higher neurocognitive functioning was found to correlate with remission.13, 26 An interesting question is whether those with higher cognitive functioning develop better adaptive strategies, and that this in turn results in lower positive and negative symptom scores, or whether there is an underlying pathology that affects cognition, negative, and positive symptoms. However, as we reported elsewhere,36 in our study population, the Dementia Rating Scale has a shared variance of about 8% with both the negative and positive symptoms scales of the PANSS, whereas the shared variance between the latter two was 25%. This suggests that there is probably not a single underlying biological factor among these three variables, and that different biological factors and/or psychosocial factors may play a role in the associations among them.

Remission was also associated with having a greater proportion of intimates among one’s network members. This finding was consistent with the gerontological literature on the beneficial effects of social supports on psychopathology.37 It also resembles studies among younger schizophrenia patients such as those of Harvey and coauthors38 on social connectedness and the work of Torgalsbøen and Rund39 on the favorable effects of supportive family relationships. A paradoxical finding in our study was that remission was associated with fewer overall social ties, despite being associated with a greater proportion of intimate ties. This association with fewer network contacts remained even after controlling in logistic regression analysis for the impact of other variables, especially residential status and mental health treatment. When we looked more closely, we found that the association with smaller network size was due to having disproportionately fewer non-kin members. Persons in remission had more kin and agency contacts. Thus, proportionately more non-intimate ties with non-kin members are associated with lower levels of remission. Because of the cross-sectional nature of the data, it is unclear whether fewer intimate kin and agency contacts leads to lower rates of remission, or whether persons with more clinical symptoms have difficulty establishing more ties with kin and agency contacts, both of which may be more conducive for the sharing of intimate thoughts and the receipt of emotional support.

Finally, it was noteworthy that having fewer accumulated lifetime traumatic events was associated with remission. There is a well established relationship between traumatic events and schizophrenia; although Morgan and colleagues40 point out that the assumption of a causal linkage remains “controversial and contestable.” Several authors40, 41 have found that early trauma such as child abuse is associated with worse outcome among persons with schizophrenia. Our data extend the findings about lifetime trauma into later life. Our findings suggest that a combination of early and later factors were associated with worse outcome. Further studies will be needed to clarify whether traumatic events result in worse outcome or whether persons with worse outcome are more prone to experience traumatic events, or whether there is a bidirectional effect.

In summary, this is the first study that has used the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group’s criteria with older adults with schizophrenia. It has several strengths: it has one of the largest samples of older persons with schizophrenia; our sample focuses specifically on older adults (age 55 and greater) rather than a mixed group of young, middle-aged, and older persons; it is a multiracial sample from a large urban area in the Northeast; and we employ a model that allows for the rational inclusion of 18 predictor variables that are then examined concurrently in a multivariate analysis. However, the findings must be interpreted cautiously because it is limited by the cross-sectional nature of the data, it is restricted to one geographic area, the schizophrenia respondents were not randomly selected but represent a convenience sample derived from a variety of residential and clinical sites, and consequently, persons not in treatment and in institutions were not included. Moreover, although we included a measure of stability—i.e., no hospitalizations in the past year—it differed from the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group’s criteria of six months of symptom stability. Finally, the large number of variables in the logistic regression analysis raises the possibility of a type 1 error.

Nevertheless, this study demonstrates that the remission rates based on our data are consistent with rates reported in the literature on younger adults, and more importantly, that symptomatic remission is an attainable goal in older persons with schizophrenia. The fact that the variables significantly associated with remission included clinical (cognition) and psychosocial (social networks, lifetime trauma) factors that are potentially remediable, suggests that even greater levels of remission can be realized. Because the number of older adults with schizophrenia will double over the next two decades,42 there are compelling reasons to replicate our study and to develop age-appropriate clinical techniques for strengthening those factors associated with symptomatic remission.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant numbers SO6GM54650 and SO6GM74923

Footnotes

No Disclosures to Report

References

- 1.Kraeplin E. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. New York: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co. Inc; 1971. [1919] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawa A, Snyder SH. Schizophrenia: diverse approaches to a complex disease. Science. 2002;296:692–695. doi: 10.1126/science.1070532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Jr, Kane JM, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:441–449. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Os J, Burns T, Cavallaro R, et al. Standardized remission criteria in schizophrenia. Acta Psychaitr Scand. 2006;113:91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Os J, Drukker M, a Campo J, et al. Validation of remission criteria for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2000–2002. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hert MD, van Winkle R, Wampers M, et al. Remission criteria for schizophrenia: Evaluation in a large naturalistic cohort. Schizophr Res. 2007;92:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auslander L, Jeste D. Sustained Remission of Schizophrenia Among Community-Dwelling Older Outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1490–1493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George LK. Social and economic factors. In: Blazer DG, Steffens DC, Busse EW, editors. Textbook of Geriatric Psychiatry. Third Edition. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeste DV, Symonds LL, Harris MJ, et al. Non-dementia non-praecox dementia praecox? Late-onset schizophrenia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997;5:302–317. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199700540-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn RL, Goldfarb AI, Pollack M, et al. Brief objective measures for the determination of mental status in the aged. Am J Psychiatry. 1960;117:326–328. doi: 10.1176/ajp.117.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarit SH, Miller NE, Kahn RL. Brain functioning, intellectual impairment and education in the aged. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1978;26:58–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1978.tb02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A. Manual. North Tonawanda N.Y: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. Positive and Negative Scale. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helldin L, Kane JM, Karilampi U, et al. Remission and cognitive ability in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeste DV, Twamley EW, Eyler Zorrilla LT, et al. Aging and outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:336–343. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrans CE, Powers MJ. Quality of life index: development and psychometric properties. Advances in Nursing Science. 1985;8:15–24. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radloff LS. The Centre for Epidemiology studies depression scale. A self-report depression for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements. 1977;3:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawton MP, Moss M, Fulcomer M, et al. A research and service-oriented Multilevel Assessment Instrument. J Gerontology. 1982;37:91–99. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sokolovsky J, Cohen CI. Toward a resolution of methodological dilemmas in network mapping. Schizophrenia Bull. 1981;7:109–116. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, et al. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattis S. Geriatric Psychiatry. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1976. Mental status examination for organic mental syndrome in the elderly patient; pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen CI, Ramirez M, Teresi J, et al. Predictors of becoming redomiciled among older homeless women. Gerontologist. 1997;37:67–74. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunally JC. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw Hill; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hseih FY. Sample size tables for logistic regression. Statistics in Medicine. 1989;8:795–802. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helldin L, Kane JM, Karilampi U, et al. Remission in prognosis of functional outcome: A new dimension in the treatment of patients with psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson D, Woerner M, McMeniman M, et al. Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:473–479. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bleuler M. A 23-year longitudinal study of 208 schizophrenics and impressions in regard to the nature of schizophrenia. New York: Pergamon Press; 1968. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harding C, Brooks G, Ashikaga T, et al. The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness II. Long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:727–735. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.6.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huber G, Gross G, Schuttler R, et al. Longitudinal studies of schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:592–605. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciompi L. Catamnestic long-term study on the course of life and aging of schizophrenics. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:606–618. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mason P, Harrison G, Glazebrook C, et al. Characteristics of outcome in schizophrenia at 13 years. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167:596–603. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieberman JA. Neurobiology and the natural history of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:e14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrow M, Grossman L, Jobe TH, et al. Do patients with schizophrenia ever show periods of recovery? A 15 year multi-follow-up study. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:723–734. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novick D, Haro JM, Suarez D, et al. Symptomatic remission in previously untreated patients with schizophrenia: 2-year results from the SOHO study. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:1015–1022. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leucht S, Beitinger R, Kissling W. On the concept of remission in schizophrenia Psychopharmacology. 2007;194:453–461. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0857-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diwan S, Cohen CI, Vahia I, et al. Correlations Among Symptom and Social Outcome Categories in Older Adults with Schizophrenia: Implications for Recovery and Treatment. AAGP. 2008 Poster Abstracts, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 37.George LK. Socioeconomic status and health across the life course: progress and prospects. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:135–139. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harvey CA, Jeffreys SE, McNaught AS, et al. The Camden Schizophrenia Surveys. III: Five-year outcome of a sample of individuals from a prevalence survey and the importance of social relationships. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2007;53:340–356. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torgalsbøen AK, Rund BR. "Full recovery" from schizophrenia in the long term: a ten-year follow-up of eight former schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry. 1998;61:20–34. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1998.11024816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgan C, Fisher H. Environment and schizophrenia: environmental factors in schizophrenia: childhood trauma--a critical review. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:3–10. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lysaker PH, Meyer PS, Evans JD, et al. Childhood sexual trauma and psychosocial functioning in adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1485–1488. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.11.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vahia I, Reyes P, Bankole AO, et al. Schizophrenia in later life. Aging Health. 2007;3:393–396. [Google Scholar]