Abstract

Excess substrate has been identified as an unintended spectator ligand affecting enantioselectivity in the [2+2+2] cycloaddition of alkenyl isocyanates with tolanes. Replacement of excess substrate with an exogenous additive affords products with consistent and higher ee’s. The increase in enantioselectivity is the result of a change in composition of a proposed rhodium(III) intermediate on the catalytic cycle. The net result is a rational probe of a short-lived rhodium(III) intermediate, and gives insight that may have applications in many rhodium catalyzed reactions.

The efficacy of transition-metal catalyzed transformations relies ultimately on the ability to finetune the chemical environment of a metal catalyst in different ways. One can alter catalyst activity both electronically and sterically by manipulating the ligand environment, which can lead to changes in product, chemo-, regio- and enantioselectivity. Understanding the mechanistic details of these observed changes can lead to synthetically useful solutions resulting from manipulation of unobserved reaction intermediates. Additives have been recognized as indispensible tools in an effort “towards perfect asymmetric catalysis”.1 A handful of reports describe changes in selectivity with the introduction of spectator (chiral or achiral) ligands, but the source of these effects remains unaddressed.2,3 Herein we describe an extraordinary example of substrate-dependent enantioselectivity in the [2+2+2] cycloaddition of tolanes and alkenyl isocyanates. Investigation of this substrate dependence implicated participation of excess alkyne as a spectator ligand, a possibility that has not been recognized. This insight inspired us to introduce an exogenous spectator ligand to standardize enantioselectivity across a range of substrates. The role of rhodium(III) coordination chemistry in the enantioselectivity of this reaction suggests that manipulation of these intermediates may improve other rhodium catalyzed reactions.4

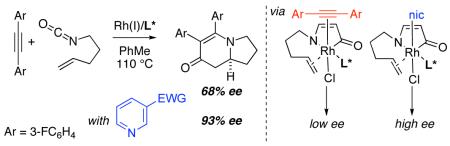

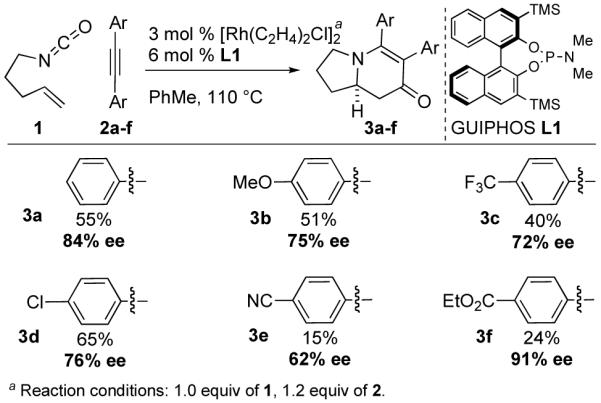

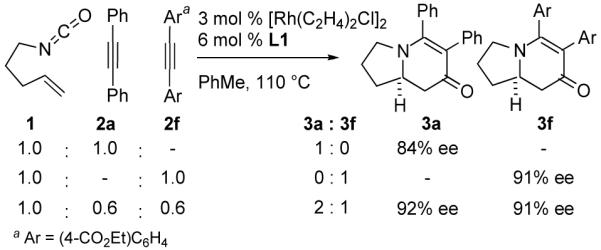

In the context of our recent studies on asymmetric rhodium-catalyzed [2+2+2] cycloadditions involving alkenyl isocyanates,5,6 we had occasion to study diaryl acetylenes (tolanes). The advent of GUIPHOS (L1) proved crucial for obtaining high enantioselectivities with product selectivity favoring vinylogous amide adduct 3 (Fig. 1).7

Figure 1.

Substrate Dependent Enantioselectivity

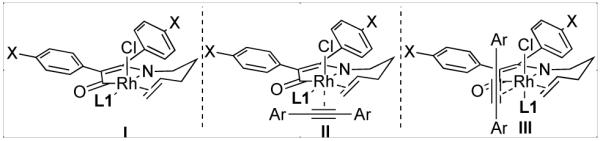

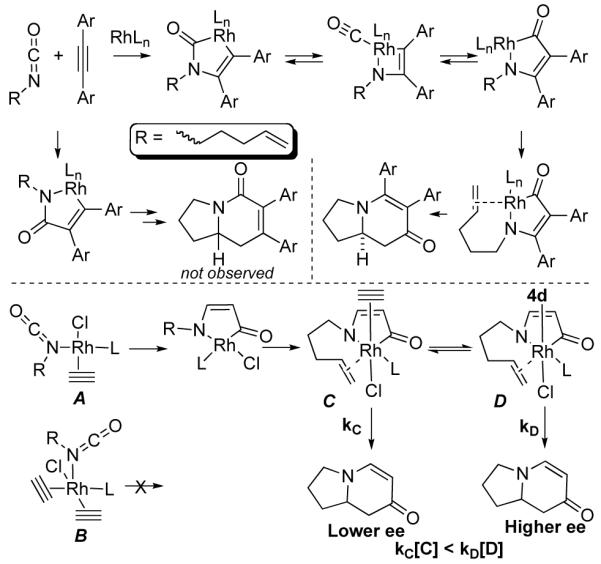

An initial substrate screen revealed extreme variation in enantioselectivity (Fig. 1). No linear trend was reconcilable on the basis of either sterics or electronics. Sterically, the para-substituent is much too distant to undergo through-space interactions with either the ligand or the olefin-metal bond, while electronic communication through π bonds is restricted since the arene rings are likely bent out of coplanarity due to strong A1,3 strain (I in Fig. 2). Alternately, this variation may be explained by coordination of a second alkyne on an octahedral rhodium(III) intermediate (II or III) rather than a 5-coordinate intermediate (I) (Fig. 2).8

Figure 2.

Potential Diastereomeric Olefin Insertion Precursors

Olefin insertion into the rhodacycle thus occurs through several possible diastereomers, via transition states whose relative energy is affected by the close electronic and steric communication with the spectator alkyne, leading to product with variant ee’s.9

As a test of this hypothesis, we designed a competition experiment between two different alkynes, which alone give products of different ee (Fig. 3). In this experiment, the ee of 3a was affected by the presence of 2f in the reaction mixture. This result is consistent with a second alkyne present during the enantiodetermining step (Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

Alkyne Competition Experiment

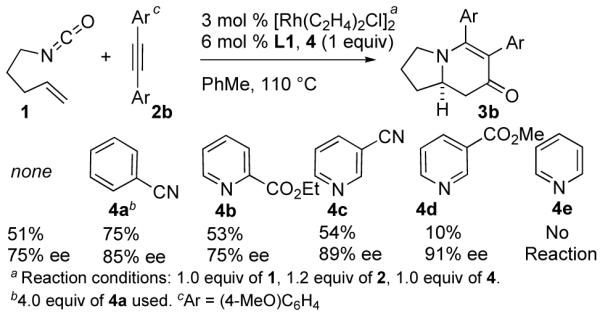

During the course of these studies, we noted that electronically similar substrates 2e and 2f gave disparate enantioselectivities presumably due to the Lewis basicity of the nitrile and its ability to coordinate to rhodium. In an effort to identify an exogenous additive that would not participate in the cycloaddition, we hypothesized that weak Lewis bases might be appropriate surrogates for alkynes in this reaction. Indeed, both nitriles and pyridines affect enantioselectivity (Fig. 4). The more Lewis basic pyridine-type additives provide a larger increase in ee than nitriles, presumably a reflection of their ability to out-compete alkynes for coordination, with nicotinate 4d proving optimal. Furthermore this competition between additive vs. alkyne as spectator ligand is illustrated by the effect of the amount of additive on enantioselectivity. At stoichiometric levels of additive high ees are obtained at the expense of yield. At substoichiometric levels of additive changes in ee are noticeable but are not optimal.10 Pyridine inhibits the reaction completely. At this point methyl nicotinate 4d was chosen as the additive to optimize in the reaction, as it gave the highest levels of enantioselectivity. To combat the decrease in yields using methyl nicotinate, excess isocyanate was used. Although nicotinate 4d is not consumed,11 it may lead to unwanted side products (dialkyl ureas, carbamates, etc.) either by slowing the reaction (vide infra), bringing in excess water (due to its hygroscopic nature), or catalyzing potentially unwanted side reactions.

Figure 4.

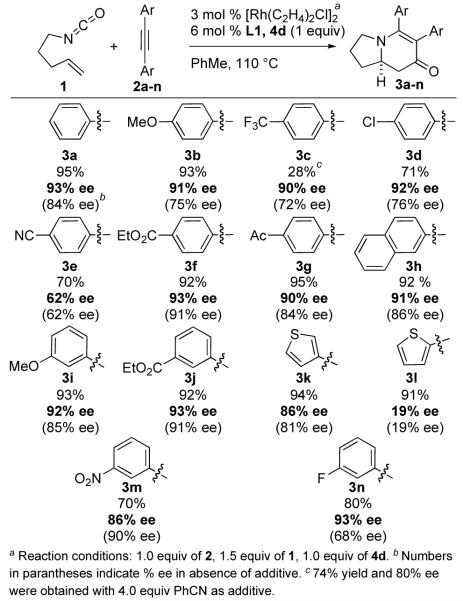

Additive Enhancement of Enantioselectivity

Products from a series of tolanes were obtained in excellent yields12 and enantioselectivities using these optimized reaction conditions (Fig. 5). The decrease in efficiency of some electron deficient substrates with a given additive can be attenuated by altering the basicity of the additive (see 3c, Fig. 5).13 With the exception of alkynes 2e and 2l, all tolanes now produce adduct within a narrow window of selectivity, suggesting that we have leveled the factors that led to spurious results. This is most consistent with the additive acting as the sixth ligand on rhodium during the olefin insertion event.

Figure 5.

Tolane Substrate Scope in Presence of Additive

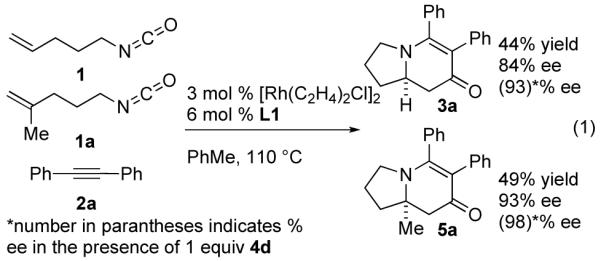

A competition experiment between two different alkenyl isocyanates yields the respective products in a 1:1 ratio (eq. 1). This result suggests that the first irreversible step does not involve the alkene and is consistent with our proposed mechanism wherein the isocyanate, alkyne and rhodium initially engage in an oxidative cycloaddition (Fig. 3).14

|

(1) |

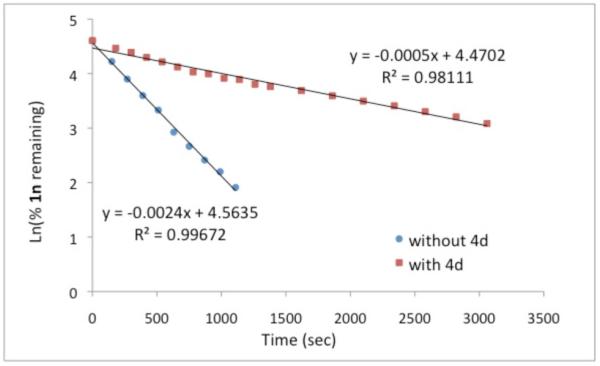

Elucidation of this first irreversible step allowed us to probe the composition of the complex undergoing oxidative cyclization. By monitoring the disappearance of substrate we were able to determine that the reaction is first order in alkyne, Graph 1.15 This data is consistent with an oxidative cyclization step occurring from a four-coordinate intermediate A rather than a five-coordinate intermediate B (Fig. 6). The order of alkyne does not change in the presence of additive.16

Graph 1.

Consumption of 1n in cycloaddition as followed by 19F NMR (presence and absence of 4d).

Figure 6.

Proposed Mechanism and Role of the Additive

In light of these observations, it is clear that the spectator ligand is affecting the enantioselectivity after the oxidative cyclization by modifying a Rh(III) intermediate, C or D, prior to or during olefin insertion.17 Importantly, we are probing the coordination environment of a metal and altering its reactivity in the kinetically invisible regime after the first irreversible step.

We have shown that excess substrate may act as an unintended ligand on a Rh-catalyzed cycloaddition leading to variant selectivities. In the presence of methyl nicotinate, the influence of substrate electronics is attenuated. We attribute this effect to a change in the ligand environment of a presumably short-lived rhodium(III) intermediate. We suggest these findings may have broad impact in other metal-catalyzed transformations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank NIGMS (GM080442) for support. TR thanks the Monfort Family Foundation for a Monfort Professorship. We thank Johnson Matthey for a generous loan of Rh salts. We thank Prof. Matthew Shores (CSU) for helpful discussions.

References

- (1).Vogl EM, Groger H, Shibasaki M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1570. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990601)38:11<1570::AID-ANIE1570>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Additives have been previously implicated as affecting enantioselectivity as well as product selectivity of Rh-catalyzed processes.Duursma A, Hoen R, Schuppan J, Hulst R, Minnaard AJ, Feringa BL. Org Lett. 2003;5:3111. doi: 10.1021/ol035106o.Hoen R, Boogers JAF, Bernsmann H, Minnaard AJ, Meetsma A, Tiemersma-Wegman T, de Vries AHM, de Vries JG, Feringa BL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4209. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500784.Selvakumar K, Valentini M, Pregosin PS, Albinati A. Organometallics. 1999;18:4591.Evans PA, Nelson JD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:1725.

- (3).For reviews on the use of the use of both chiral and achiral pairs of ligands, see:Reetz MT. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2556. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704327.For a supramolecular approach, see:Breit B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:6816. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501798.

- (4).Evans PA. Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Yu RT, Rovis T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2782. doi: 10.1021/ja057803c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu RT, Rovis T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12370. doi: 10.1021/ja064868m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee EE, Rovis T. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1231. doi: 10.1021/ol800086s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yu RT, Rovis T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3262. doi: 10.1021/ja710065h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yu RT, Lee EE, Malik G, Rovis T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2379. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Friedman RK, Rovis T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:10775. doi: 10.1021/ja903899c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Dalton DM, Oberg KM, Yu RT, Lee EE, Perreault S, Oinen ME, Pease ML, Malik G, Rovis T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009 doi: 10.1021/ja905065j. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).For reviews on [2+2+2] cycloadditions of alkynes see:Saito S, Yamamoto Y. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2901–2915. doi: 10.1021/cr990281x.Agenet N, Busine O, Slowinski F, Gandon V, Aubert C, Malacria M. Org. React. 2007;68:1–302.Tanaka K. Synlett. 2007:1977–1993.Galan BR, Rovis T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2830–2834. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804651.For reviews on [2+2+2] cycloadditions of alkynes and nitrogen moieties see:Varela JA, Saá C. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:3787–3801. doi: 10.1021/cr030677f.Heller B, Hapke M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1085–1094. doi: 10.1039/b607877j.Chopade PR, Louie J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006;348:2307–2327.

- (7).TADDOL-PNMe2: 57%, 9% ee. MONOPHOS: 74%, 39% ee.

- (8).A search of the Cambridge Crystallographic Database revealed 738 six-coordinate monomeric rhodium(III) complexes, while only 106 five-coordinate and 3 four-coordinate complexes.

- (9).A number of different diastereomeric intermediates may be envisioned; those in Figure 1 are presented as reasonable suggestions.

- (10).In the reaction of 1 and 2a with 3 mol % Rh dimer and 6 mol % L1, the following results were obtained: 0 equiv 4d = 55%, 84% ee; 0.05 equiv 4d = 53%, 86% ee; 0.4 equiv 4d = 52%, 91% ee; 0.8 equiv 4d = 45%, 93% ee; 1.6 equiv 4d = 32%, 93% ee.

- (11).1H NMR analysis of unpurified reaction mixtures shows good mass balance of nicotinate remaining at the end of the reaction (92%).

- (12).Excess isocyanate was used due to the increased formation of dialkyl ureas in the presence of methyl nicotinate.

- (13).Tolanes bearing pyridines or unprotected aldehydes are not tolerated.

- (14).For a discussion of the current proposed mechanism, see refs. 5b and 5g.

- (15).The disappearance of alkyne 2n over time was followed by 19F NMR. The linear shape of the graph indicates a first order dependence on alkyne (see Supporting Information).

- (16).The slowing of the rate is also consistent with inhibition of the oxidative cyclization by methyl nicotinate.

- (17).No other intermediates were observed in the 31P or 19F in the course of the reaction.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.