Abstract

A distinct gene family of widely distributed and well-modulated two-pore-domain background potassium (K2P) channels establish resting membrane potential and cell excitability. By using new mouse models in which K2P-channel genes are deleted, the contributions of these channels to important physiological functions are now being revealed. Here, we highlight results of recent studies using mice deleted for K2P-channel subunits that uncover physiological functions of these channels, mostly those of the TASK and TREK subgroup. Consistent with activation of these K2P channels by volatile anesthetics, TASK-1, TASK-3 and TREK-1 contribute to anesthetic-induced hypnosis and immobilization. The acid-sensitive TASK channels are not required for brainstem control of breathing by CO2 or pH, despite widespread expression in respiratory-related neurons. TASK channels are necessary, however, for homeostatic regulation of adrenal aldosterone secretion. The heat-, stretch- and lipid-activated TREK-1 channels contribute to temperature and mechanical pain sensation, neuroprotection by polyunsaturated fatty acids and, unexpectedly, mood regulation. The alkaline-activated TASK-2 channel is necessary for HCO3- reabsorption and osmotic volume regulation in kidney proximal tubule cells. Development of compounds that selectively modulate K2P channels is crucial for verifying these results and assessing the efficacy of therapies targeting these interesting channels.

Introduction

The existence of prominent background, or ‘leak’, potassium conductances that generate the negative membrane potential in excitable and non-excitable cells has long been recognized (Box 1). The discovery of the KCNK gene family of two-pore-domain potassium (K2P) channels in the mid-to-late 1990s provided a molecular basis for characterizing functional properties of leak K+-channel subunits and localizing native sites of expression [1-6]. These studies have prompted several hypotheses regarding potential physiological roles of K2P channels [1-6], which have recently been evaluated using mouse genetic models.

Box 1. K2P channels, background K+ conductance and resting membrane potential.

Excitable and non-excitable cells maintain a negative resting membrane potential, the magnitude of which is determined by a weighted average of the equilibrium (Nernst) potentials for all permeant ions; the weighting factor is provided by the relative resting permeability (conductance) to each ion. In most cells, the dominant background (or leak) conductance is for potassium, which drives the resting membrane potential toward the K+ equilibrium potential (E K); the influence of other permeant ions (e.g. Cl-, Na+ and Ca2+) keeps the resting membrane potential from reaching EK. Thus, the ionic basis for the resting membrane potential is well understood; however, until recently, the molecular basis for the prominent resting K+ conductance has been more enigmatic. Theoretically, any K+ channel that retains activity around the resting membrane potential can contribute to the background K+ conductance, and persistent activity of both voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) and inwardly rectifying (Kir) channels probably plays a part in some cell contexts. However, the K2P channels, which are structurally distinct from the Kv or Kir channels, seem to be uniquely positioned to provide a leak K+ conductance. These channels display little voltage dependence and, thus, they carry K+ currents over a wide range of membrane potentials. Despite their contribution to leak K+ conductance, the activity of K2P channels is not invariant; they are strongly modulated by physicochemical factors, endogenous neurochemicals and clinically relevant drugs. This modulation can have a strong influence on electrical properties of cells. For example, inhibiting K2P channels causes membrane depolarization; this increases electrical activity in excitable cells and enhances calcium entry to provoke hormone and/or transmitter release from secretory cells or contraction in smooth muscle cells. In addition, by decreasing membrane conductance, inhibiting leak K+ channels enhances responsiveness to other inputs. Opposite effects would follow from activating K2P channels; cells hyperpolarize, leading to decreased activity and responsiveness. Thus, background K+ currents have a key role in regulating membrane potential and cellular activity and K2P channels are major contributors to those background currents.

Here, we highlight insights gleaned from study of available K2P knockout mice and emphasize where targeting these channels might be used to therapeutic advantage. Before describing these results, a brief overview of K2P-channel characteristics is provided; readers are referred to recent reviews for more exhaustive coverage of the properties of these channels [1-6]. We also discuss salient physiological and pharmacological features of the channels, with emphasis on properties relevant to functions identified in mouse models. We do not provide a compendium of available (and mostly nonspecific) channel-modulating agents, which has been ably presented elsewhere [7].

K2P channels generate well-modulated background K+ currents

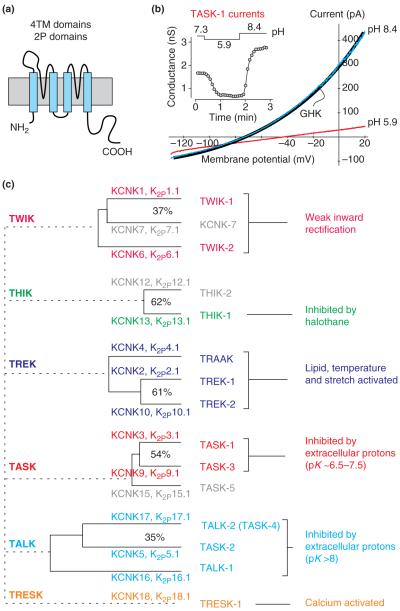

As reflected in their name, K2P subunits each contain two pore-forming loops (Figure 1a) and they form channels as dimers; this is in contrast to other types of K+-channel subunits, which have one P loop and assemble as tetramers. The established nomenclature for KCNK genes and the cognate K2P channels follows chronologically the order in which the channels were cloned [8]. Another classification system in popular use assigns K2P subunits into groups based on sequence homology and functional characteristics, with channel names representing acronyms that describe a key defining property (Figure 1c). As expected for background K+ channels, functional expression in heterologous systems reveals persistent activity of K2P channels at negative membrane potentials and weakly rectifying current-voltage (I-V) relationships (Figure 1b) distinct from those of voltage-dependent (Kv) or inwardly-rectifying (Kir) K+ channels. An additional, and particularly noteworthy, feature of K2P channels is their regulation by a variety of physicochemical factors, endogenous neurochemicals, signaling pathways and clinically relevant drugs [1-6]. Thus, these channels provide constitutive, but not invariant, background K+ conductances, and differential expression of K2P subunits can endow cells with a rich modulatory potential.

Figure 1.

Properties and organization of the K2P channel family. (a) The presumed topology for a subunit of the two-pore-domain family of background K+ channels; each subunit has two pore-forming (P) loops and four transmembrane (TM) domains. The functional channel forms as a dimer. (b) Whole-cell currents obtained from heterologous expression of TASK-1, a K2P channel sensitive to extracellular pH. As illustrated in the inset, acidifying the bath pH (from 7.3 to 5.9) inhibited TASK-1 current, whereas alkalizing the bath (from 5.9 to 8.4) increased current. The I-V curves for TASK-1 obtained at different bath pH reverse near the K+ equilibrium potential (EK) and are well-fitted by the GHK current equation, as expected for a potassium ‘leak’ current. (c) The 15 known human two-pore-domain K+-channel genes are presented in a phylogenetic tree and placed into six subgroups as described here; genes that have not produced functional channels are shown in gray. The more distant relationships between the subgroups have been omitted. Multiple naming schemes for these channels are in current use. The Human Genome Organization (http://www.hugo-international.org) uses KCNK preceding a number that reflects the order of discovery of each of the genes; the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (www.iuphar.org) adopted a very similar scheme for naming the cognate channels, replacing the KCNK with a K2P prefix. A third naming scheme that is in popular use employs a set of acronyms based on salient physiological or pharmacological properties (provided here). The acronyms are as follows: TWIK, tandem of P domains in a weak inwardly rectifying K+ channel; THIK, tandem-pore-domain halothane-inhibited K+ channel; TREK, TWIK-related K+-channel gene; TRAAK, TWIK-related arachidonic-acid-stimulated K+ channel; TASK, TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ channel; TALK, TWIK-related alkaline-pH-activated K+ channel; and TRESK, TWIK-related spinal-cord K+ channel. Here, we focus on the TASK- and TREK-channel groups.

Here, we focus on TASK (tandem of P domains in a weak inwardly rectifying K+ channel [TWIK]-related acid-sensitive K+ channel) and TREK (TWIK-related K+-channel gene) subgroups because most of the work with mouse knockout models involves these channels. The TASK subgroup of the KCNK gene family includes TASK-1 (also known as K2P3.1), TASK-3 (K2P9.1) and TASK-5 (K2P15.1). As homodimers or heterodimers, TASK-1 and TASK-3 generate archetypal K+-selective leak currents, with whole-cell I-V relationships well-described by the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) constant field equation (Figure 1b). By contrast, TASK-5 subunits seem to be nonfunctional when expressed alone or together with the other TASK subunits [9]. The TREK subgroup comprises TREK-1 (also known as K2P2.1), TREK-2 (K2P10.1) and TWIK-related arachidonic-acid-stimulated K+ channel (TRAAK; K2P4.1), all of which are functional in heterologous expression systems; whole-cell TREK-channel currents are outwardly rectifying, whereas TRAAK channels generate GHK-rectifying (see Glossary) currents [1,5,10].

At this time, there are no pharmacological agents available that are selective for TASK or TREK channels [7]. However, they are modulated by various nonspecific agents. TASK channels are inhibited by extracellular acidification and local anesthetics and activated by inhalational anesthetics [1-4]. TREK channels are renowned for their activation by stretch, intracellular acidification, raised temperature and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) [1-6]; TRAAK channels are also activated by stretch, heat and PUFAs, but they are activated by intracellular alkalization rather than acidification [4]. In the absence of selective blockers, identification of correlates for K2P channels in native tissues based on these pharmacological properties has been an imprecise exercise, and verification using knockout mice has, so far, been obtained in only a few settings.

Physiological roles and therapeutic potential of TASK and TREK channels

The availability of TASK and TREK-1 knockout mice has enabled direct evaluation of the contribution of these channels to native currents; more importantly, these mouse models have been used to examine proposed roles for TASK and TREK channels in physiological functions or drug action. As discussed here, some ideas have been borne out, whereas others have not. In other cases, unanticipated new functions for the channels have been discovered.

TASK channels regulate aldosterone secretion from the adrenal gland

The adrenal cortex is a primary site of TASK-channel expression outside of the central nervous system, with especially high levels of both TASK-1 and TASK-3 in aldosterone-synthesizing cells of the outermost zona glomerulosa (ZG) layer [11]. Aldosterone is a steroid hormone that is synthesized by the action of the Cyp11β2 (aldosterone synthase), the expression of which is localized to ZG cells. Aldosterone secretion is enhanced by increased activity of the renin-angiotensin system, elevated K+ or acidosis. It stimulates Na+ reabsorption and K+ secretion from the kidney, thereby contributing to whole-animal volume regulation and blood-pressure control. Heterologous expression of adrenocortical mRNA yields TASK-like currents, and TASK channels are inhibited by angiotensin II (AngII) and extracellular acidosis, two aldosterone secretagogues that cause K+-channel inhibition and membrane depolarization of ZG cells [12]. Together, these observations led to the hypothesis that TASK channels account for a background K+ conductance in ZG cells [12,13]. Indeed, as described here, TASK knockout mice present with dysregulated aldosterone production consistent with a primary hyperaldosteronism phenotype [14,15].

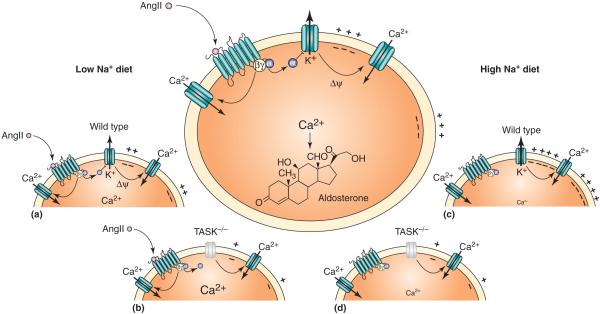

In male mice deleted for both TASK-1 and TASK-3 subunits (TASK-1-/-:TASK-3-/-; hereafter called TASK-/-), adrenal glands displayed normal histological features and typical zonal distributions of steroid-synthesizing enzymes (e.g. Cyp11β2 was localized to the ZG layer) [14]. A prominent TASK-like outward current recorded from ZG cells in wild-type mice was absent in TASK-/- animals and, consequently, the membrane potential of ZG cells from TASK-/- mice was substantially depolarized [14] (Figure 2). Importantly, compared with wild-type animals, aldosterone production in knockout mice was: (i) elevated despite low-plasma renin; (ii) substantially increased on a low-salt diet, yet not normalized to wild-type levels by AngII-receptor blockade (with candesartan); and (iii) not suppressed on a high-salt diet [14]. Overall, these characteristics of TASK-/- mice are remarkably similar to those of patients with idiopathic primary hyperaldosteronism [16-18]. These data indicate that TASK channels have an important role in regulating ZG cell-membrane potential and constraining aldosterone production (Figure 2). Drugs that increase TASK-channel activity might represent a new therapeutic avenue for lowering aldosterone levels that, together with currently available mineralocorticoid-receptor blockers, could ameliorate target-organ damage produced by aldosterone excess in treatment-resistant hypertension and heart disease [16,19,20].

Figure 2.

TASK channels regulate aldosterone production. Schematic illustrating role of TASK channels in aldosterone production from adrenal ZG cells, with proposed mechanisms for channel modulation and effects of channel deletion. Main panel: In ZG cells, TASK channels provide a background K+ current that maintains a negative membrane potential (Ψ), limiting the Ca2+ entry via T-type Ca2+ channels that drives aldosterone production and secretion. AngII-mediated inhibition of TASK channels by a Gαq-linked angiotensin AT1 receptor causes membrane depolarization, which, along with an independent calmodulin-dependent-protein-kinase-II-mediated activation of Ca2+ channels, promotes increased Ca2+ entry and aldosterone release [13]. Low Na+ diet: (a) in a wild-type mouse on a low-salt diet, elevated levels of AngII enhance ZG cell-membrane depolarization and Ca2+-channel activation, increasing aldosterone production. (b) In TASK-/- mice, the absence of the background K+ conductance leads to a persistent strong depolarization of ZG cells; in this context, AngII-mediated Ca2+-channel activation greatly increases aldosterone production [14]. High Na+ diet: (c) on a high-salt diet, circulating AngII levels are low and constitutive TASK activity is high, driving the ZG cell-membrane potential to hyperpolarized levels that minimize Ca2+-channel activity and aldosterone production. (d) In TASK-/- mice, the persistent membrane depolarization maintains Ca2+-channel activity and aldosterone production even in the absence of AngII [14].

The results from male double TASK-/- mice can be contrasted with a different form of hyperaldosteronism obtained in adult female single-subunit TASK-1-/- mice [15]. In TASK-1-/- animals, a striking mis-expression of Cyp11β2 was observed in young male and female knockout mice; the aldosterone-synthesizing enzyme was excluded from ZG cells and appeared instead in the glucocorticoid-synthesizing cells of the zona fasciculata (ZF) [15]. Ectopic expression of Cyp11β2 was corrected by testosterone in adult male TASK-/- mice. However, high levels of Cyp11β2 mis-expression persisted in the ZF of adult female mice, producing elevated aldosterone despite low renin and low serum K+ (i.e. primary hyperaldosteronism) and aldosterone-dependent hypertension [15]. Inasmuch as the elevated aldosterone and hypertension were corrected by treatment with dexamethasone, these female TASK-1-/- mice represent a model of glucocorticoid-remediable hyperaldosteronism [15]. In humans, this disorder is commonly caused by a gene-crossover event involving Cyp11β1 and Cyp11β2 [21] and, thus, is mechanistically distinct from this TASK-1-/- model. However, TASK-1-channel dysfunction might contribute to other cases in which the genetic cause has not been determined.

TASK channels are not necessary for central respiratory chemosensitivity

In a homeostatic process, blood and tissue levels of O2 and CO2 and/or pH are regulated by the rate and depth of breathing, and those same factors act, in turn, on peripheral and central chemoreceptors to modulate output of the brainstem system that controls ventilation. The intrinsic pH and O2 sensitivity of TASK channels, combined with demonstrated functional expression of TASK-like currents in various elements of the respiratory control system, led to the suggestion that TASK channels participate in chemical control of breathing [2,22].

Two neuronal groups are considered to be strong candidates for mediating central respiratory chemoreception: serotonin-containing raphe neurons [23] and paired-like homeobox 2b (Phox2b)-expressing neurons of the medullary retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) [24]. Previous work identified a TASK-like background K+ current in raphe neurons [25] and, accordingly, pH sensitivity was abolished in raphe cells from TASK knockout mice. By contrast, there was no difference in pH sensitivity of RTN chemoreceptor cells in TASK knockout mice, which retained a pH-sensitive background K+ current identical to that seen in wild-type RTN neurons [26]. Importantly, CO2-evoked ventilatory responses were fully preserved in awake TASK knockout mice [26]. These data indicate that the extensive expression of TASK channels in respiratory-related brainstem neurons is not necessary for ventilatory responses to CO2, and they effectively dissociate pH sensitivity of raphe neurons from central respiratory chemosensitivity. These results also indicate that another background K+ channel underlies the pH sensitivity of RTN chemoreceptors [26].

TASK channels have been implicated in other chemosensory functions relevant to breathing and gas exchange, although these have yet to be verified in mouse knockout models. Glomus (Type I) cells of the carotid bodies sense arterial O2 and CO2. In these cells, an O2-sensitive K+ current with properties expected from TASK channels was identified [27,28]. Based on this, it was proposed that inhibition of TASK channels by hypoxia and acidosis causes glomus cell depolarization and activation of peripheral chemosensory afferents [27,28]. In apparent contradiction of this hypothesis, no decrement in hypoxic ventilatory response was observed in double TASK knockout mice [26]. However, because compensatory mechanisms that might account for maintained hypoxia responses in TASK-/- mice were not ruled out, it remains a possibility that TASK channels contribute to O2 sensing in wild-type mice.

Hypoxia also depolarizes pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), causing vasoconstriction; this serves to re-direct blood flow away from poorly oxygenated regions of the lung, limiting ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatches [29]. The biophysical and pharmacological properties of the hypoxia-sensitive background K+ current in PASMCs match those of TASK channels [29] and RNA-interference-mediated knockdown of TASK-1 reduced that current in human PASMCs [30]. It remains to be determined if hypoxic ventilatory V/Q mismatches are exacerbated in TASK-1 knockout mice, as expected from these results on isolated PASMCs.

In summary, these results indicate that neither TASK-1 nor TASK-3 is necessary for central respiratory chemoreception; however, TASK channels might be important for maintenance of blood gases by curtailing V/Q mismatches and they could contribute to carotid body stimulation by O2 and CO2.

TASK and TREK-1 channels are targets for immobilizing effects of general anesthetics

Early explorations of the ionic basis for anesthetic actions in neuronal preparations identified background K+ currents activated by inhalational anesthetics, causing membrane hyperpolarization and decreased excitability [31]. It is now recognized that various K2P channels are likely substrates for these anesthetic-activated neuronal background K+ currents, including TREK-1, TREK-2, TASK-1, TASK-2, TASK-3, TWIK-related alkaline-pH-activated K+ channel (TALK)-2 and TWIK-related spinal-cord K+ channel (TRESK) [32-34]. Among these, the TASK and TREK subgroups have received the most attention because of their widespread neuronal expression [35]. In these animals, substantial decreases in sensitivity were observed for the immobilization and hypnosis produced by various inhalational anesthetics [36]. Behavioral effects of inhaled anesthetics were unperturbed in mice deleted for either TASK-2 or the apparently nonfunctional K2P7.1 subunit [37,38]. In both TASK-1 and TASK-3 knockouts, however, immobilization required significantly higher concentrations of halothane (but not isoflurane), whereas a slight, but significant, shift in hypnotic sensitivity was reported only for isoflurane in TASK-1-/- mice [39,40]. The neural substrates for these actions remain to be determined. For immobilization, a spinally mediated effect, it is possible that TASK channels in motoneurons [41] and TREK-1 channels in sensory neurons could be the relevant targets [42]. Hypnotic actions might involve actions on these channels in noradrenaline- or serotonin-synthesizing neurons and/or thalamocortical neurons, cell groups that express TASK and TREK channels and contribute to altered states of arousal [25,41,43,44].

Further exploration of the roles of these and other anesthetic-activated K2P channels could yield a better understanding of the enigmatic behavioral effects of anesthetics. In addition, compounds that selectively activate individual K2P channels might ultimately permit achievement of desirable anesthetic outcomes while minimizing unwanted side effects.

TREK-1 channels mediate neuroprotection by PUFAs

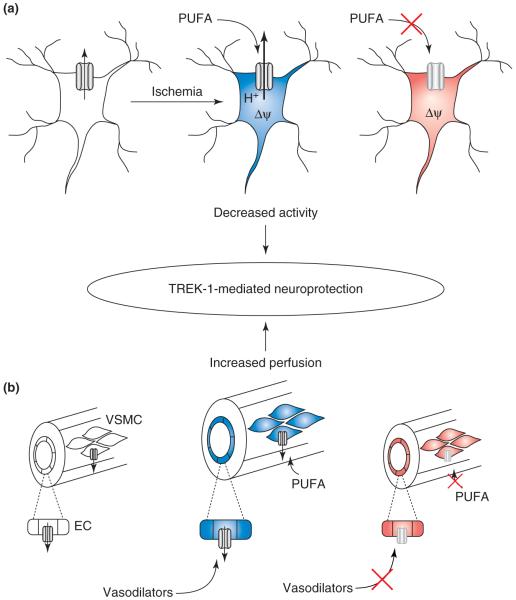

TREK-1 channels are activated by intracellular acidification and by PUFAs known to provide neuroprotection from cerebral ischemic insult [5]. Based on this, a role for TREK-1 was sought in a bilateral carotid artery occlusion model of cerebral ischemia; compared with control mice, TREK-1-/- mice were significantly less likely to survive the ischemic insult [36]. Moreover, the protection from ischemia typically afforded by linolenic acid (LIN) or lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) was absent in TREK-1-/- mice [36]. Two mechanisms could account for neuroprotection by TREK-1 channels (Figure 3). First, activation of TREK-1 channels during ischemia (perhaps secondary to intracellular acidification) would limit neuronal activity and, thereby, decrease metabolic requirements. Additional TREK-1 activation in neurons by LIN or LPC would provide further protection [36]. A second potential mechanism follows the discovery that TREK-1 is expressed in endothelial and smooth muscle cells of cerebral arteries and the realization that TREK-1 channels (i) are necessary for receptor-mediated generation of nitric oxide (NO) by vasodilators in endothelial cells and (ii) contribute directly to hyperpolarizing and relaxing effects of PUFAs on vascular smooth muscle [45]. Indeed, in TREK-1 knockout mice, the endogenous vasodilator substance acetylcholine was unable to relax basilar arteries in vitro and LIN was unable to cause basilar artery vasodilation in vitro or enhance cerebral blood flow in vivo [45]. These data indicate that activation of TREK-1 channels decreases neuronal activity and enhances collateral blood flow during cerebral ischemia, both effects serving to minimize neuronal damage.

Figure 3.

Neuroprotection mediated by TREK-1 channels. In cerebral ischemia models, TREK-1-/- mice have reduced survival rates and are insensitive to the neuroprotective actions of PUFAs [36]. Two mechanisms conspire to account for this neuroprotection. (a) During ischemia in neurons, TREK-1 activation by intracellular acidification and by PUFAs leads to membrane hyperpolarization, decreasing activity and lowering metabolic demand. In TREK-1 knockouts, the neurons would be more depolarized and unresponsive to PUFAs. Blue indicates a more negative membrane potential and less activity; red indicates a depolarized state with more activity. (b) In cerebral blood vessels, TREK-1 is necessary for actions of endogenous vasodilators (e.g. acetylcholine) in endothelial cells (EC) and is activated directly by PUFAs in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), leading to vasodilation and enhanced collateral blood flow [45].

Deletion of TREK-1 yields depression-resistant phenotype

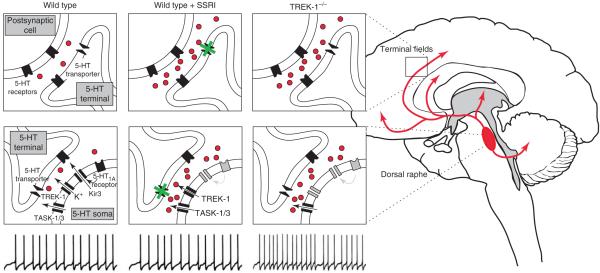

In TREK-1 knockout mice, a remarkable depression-resistant phenotype was discovered [43]. This phenotype was demonstrated across several well-established assays in which TREK-1-/- mice displayed a lower incidence of behaviors representative of helplessness and despair. In addition, these depression-resistant animals were insensitive to actions of antidepressant drugs, including serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), indicating that mechanisms targeted by those drugs were already engaged [43]. Indeed, this depression-resistant phenotype was attributed to increased activity of serotonin neuronal systems (Figure 4) because (i) TREK-1 channels were immunolocalized to dorsal raphe neurons in control animals, (ii) firing activity of dorsal raphe neurons was elevated in TREK-1-/- mice and (iii) serotonin tone was increased in the hippocampus of TREK-1-/- mice [43]. These data indicate that TREK-1 channels normally limit firing activity in dorsal raphe neurons; this could be a direct consequence of TREK-1 expression in raphe neurons [43], although a TREK-1-like current has not been directly demonstrated in those cells. In this respect, TASK-like currents have been identified in serotonin-synthesizing raphe neurons [25], suggesting by analogy that inhibition of those channels might also have antidepressant effects. Development of compounds that inhibit TREK-1 (and perhaps TASK channels) might, thus, provide a new therapeutic avenue for treating depression. Interestingly, several SSRIs inhibit TREK-1 channels directly, raising the possibility that TREK-1-channel modulation could account for some therapeutic actions of existing antidepressant drugs [7,43,46].

Figure 4.

Depression-resistant phenotype in TREK-1 knockout mice. Serotonin-synthesizing neurons of the dorsal raphe nucleus have widespread ascending projections to terminal fields in the forebrain (red in brain schematic). In wild-type mice, firing activity in dorsal raphe neurons yields basal levels of serotonin in the raphe nucleus and in terminal fields (indicated by red dots). It is possible to evoke behavioral correlates of despair and helplessness in these wild-type animals that can be ameliorated by treatment with antidepressants (e.g. SSRIs) [43] by virtue of their ability to inhibit the 5-HT transporter and increase serotonin tone in terminal fields [61]. Note that chronic treatment with SSRIs leads to a functional desensitization of 5-HT1A-receptor-dependent, Kir-channel-mediated autoinhibition of dorsal raphe neurons, enabling those cells to maintain normal discharge rates despite increased local serotonin levels [61]. In TREK-1-/- mice, action-potential discharge rate is doubled in dorsal raphe neurons and this leads to increased serotonin levels in terminal fields that yield a depression-resistant phenotype and occlude further effects of SSRI treatment [43]. In these animals, chronically high levels of serotonin presumably desensitize 5-HT1A-receptor-dependent autoinhibition of raphe neurons to permit high basal firing rates [61]. The increase in excitability of serotonin neurons in TREK-1-/- mice and accompanying depression-resistant phenotype could reflect loss of the channel directly from dorsal raphe neurons [43]. Inhibition of TREK channels might, thus, provide an alternative approach to antidepressant therapy. Note that both TASK-1 and TASK-3 are also expressed in dorsal raphe neurons [25], indicating that inhibition of those channels might represent an additional therapeutic mechanism to enhance serotonin neuron activity.

TREK-1 contributes to select pain modalities

TREK-1 channels are co-expressed with the heat-activated transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) capsaicin receptor in small-to-medium-diameter nociceptor neurons of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [42]. Accordingly, an arachidonic-acid-activated TREK-1-like current recorded in nearly all capsaicin-sensitive, small-diameter DRG neurons of wild-type mice (>90%) was absent in those neurons from TREK-1-/- mice [42]. Single C-fiber recordings in skin-nerve preparations from TREK-1 knockout mice revealed heightened sensitivity to raised temperature over a range where TREK-1 channels are strongly activated (30-45 °C). This indicates that heat-induced activation of TREK-1 currents typically counterbalances inward currents carried by TRPV1 channels. Consistent with this, TREK-1-/- mice displayed a lower response threshold for noxious heat [42]. Activation of cold-sensitive C fibers and the behavioral response to cold induced by acetone were preserved in TREK-1-/- mice, indicating that a different temperature-sensitive K+ channel (e.g. perhaps TREK-2 or TRAAK) accounts for the cold-inhibited background K+ current in cold nociceptors [47]. Other sensory responses are also influenced by TREK-1 currents. For example, enhanced sensitivity to mechanical stimuli was observed in TREK-1-/- mice [42], indicating that activation of stretch-sensitive TREK-1 channels by mechanical distortion normally counters actions of excitatory mechanosensitive ion channels. In addition, increased pain sensitivity associated with inflammation was reduced in TREK-1-/- mice [42]. In this case, the effect was attributed to removal of an ion channel that normally contributes to actions of inflammatory mediators (e.g. TREK-1 inhibition by prostaglandin E2). In summary, these results indicate that drugs targeting TREK-1 channels could find use in pain treatment; channel activators might increase threshold for thermal and/or mechanical pain, whereas interfering with TREK-1 inhibition by inflammatory mediators could mitigate hyperalgesia associated with inflammation.

TASK-2 is an alkaline-activated K+ channel involved in HCO3- reabsorption

The TASK-2 channel, despite its name, is not considered part of the TASK subgroup of K2P channels; rather, it is included in the TALK subgroup of alkaline-activated channels (Figure 1). TASK-2 knockout mice were used to demonstrate the importance of channel activation by alkalization in kidney function [48]. To maintain HCO3- flux in the proximal tubule, a K+ conductance activated by local HCO3--mediated alkalization in the external basolateral space is needed to offset the depolarizing influence of the electrogenic Na+-3-HCO3- cotransporter. This alkalization-activated K+ current is dramatically reduced in TASK-2 knockout mice [48]. Likewise, activation of TASK-2 by local HCO3--mediated alkalization is necessary for cell-volume regulation in proximal tubule cells, providing protection from osmotic cell swelling that might, otherwise, accompany electrolyte reabsorption [49,50]. Consistent with the idea that TASK-2 is necessary for normal HCO3- reabsorption in vivo, the knockout mice show symptoms of metabolic acidosis under control conditions and displayed deficits in Na+ and water handling during HCO3- infusion [48]. It remains to be determined whether mutations in TASK-2 account for familial forms of human proximal renal tubular acidosis, which these mice seem to phenocopy [48], or whether compounds that activate TASK-2 might be useful in treating metabolic acidosis.

Potential roles for K2P channels that remain to be tested in vivo

Several other potential physiological roles for TASK and TREK channels (and for other K2P channels) are yet to be tested in knockout mice. For example, TASK channels have been implicated in glucosensing by hypothalamic orexin neurons, providing a link between metabolic status and behavioral arousal [28,51], and possibly accounting for the increase in nocturnal activity observed in TASK-3-/- mice [39]. Also, TASK-1 (but not TASK-3) is strongly expressed in the heart, where it might underlie a background K+ current inhibited by α1-adrenoceptors and platelet-activating factor in cardiomyocytes [52,53]. Another cardiomyocyte background K+ current, attributed to TREK-1, is inhibited by β-adrenoceptors [54]. TASK channels are expressed in lymphocytes, where they could contribute to inflammatory responses [55], and TASK-3 and TREK-1 are overexpressed in breast and prostate cancer cells, where they support cell proliferation and tumorigenesis [56,57]. The TALK channels are highly expressed in exocrine pancreas, where their activation by NO and reactive oxygen species is striking and where they could have a role in NO effects on pancreatic secretion [58]. In DRG neurons, the TRESK-channel subunit is highly expressed and might contribute to various sensory modalities and/or to anesthetic-induced immobilization [59]. This brief list is far from inclusive, but is meant to draw attention to the need for further study into the roles of this interesting group of channels.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

In conclusion, K2P channels produce background K+ currents that regulate cell excitability. These channels are distributed widely in the central nervous system and periphery, with differential, but often overlapping, expression patterns. They also possess a rich modulatory capacity that can underlie multiple distinct cell-regulatory mechanisms. The availability of mice in which K2P channels are deleted has been illuminating; despite widespread expression and contributions to crucial cell properties, K2P-gene deletion has proved remarkably benign on unstressed mice. Nevertheless, under physiological or behavioral challenge, TASK and TREK-1 knockout mice have revealed key contributions of those channels to several important functions (Figure 5). Of particular note, these studies indicate that TASK and TREK channels might represent novel drug targets for several disorders for which additional therapeutic options would be useful (e.g. hyperaldosteronism, allodynia or inflammatory pain, and depression). Although further exploration of available and new K2P-channel knockout mice is expected to yield additional insights into physiological roles of the different members of this interesting K+-channel family, our understanding of K2P-channel function would also benefit tremendously from identification of subunit-selective blockers, which are currently nonexistent.

Figure 5.

Summary of physiological roles for TASK and TREK-1 channels. (a) TASK channels are inhibited by extracellular acidification (pHe), local anesthetics and Gαq-linked G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). They are activated by phospholipids and by volatile anesthetics. In knockout mice, a role for TASK channels has been demonstrated in aldosterone production from adrenal ZG cells [14] and in immobilizing actions of inhaled anesthetics [39,40]. A marked increase in nocturnal activity has also been found in TASK-3-/- mice [39]. Other prominent ideas remain to be tested in these mice, including effects on glucosensing [28,51], immune-cell proliferation [55] and heart-rate regulation [52,53]. (b) TREK-1 channels are activated by PUFAs, phospholipids, stretch, volatile anesthetics, intracellular acidification (pHi) and raised temperature (T°C). They are inhibited by Gαs- and Gαq-linked GPCRs through protein kinase (PK)A and PKC, but activated by a PKG-mediated mechanism [5]. In knockout mice, a role for TREK-1 has been demonstrated in neuroprotection [36] and cerebral artery vasodilation [45], in hypnotic and immobilizing actions of inhaled anesthetics [36], in depression [43] and in pain sensation [42]. A role for TREK-1 in tumorigenesis has been suggested but not tested in knockout mice [57].

Update

During the preparation of this article, new data appeared verifying that TASK channels are not required for central respiratory chemoreception (see also Ref. [26]) and indicating that TASK-1 (but not TASK-3) has a role in peripheral chemoreception [60]. Specifically, O2- and CO2-induced chemoafferent cell firing was strongly reduced (by ~50-70%) in nerve recordings from carotid body explants of TASK-1-/- mice, and ventilatory responses to hypoxia were blunted in TASK-1-/- mice but unchanged in TASK-3-/- mice. In double TASK-/- knockout mice, there was no additional decrement in activation of chemoafferent cell firing by O2 and CO2, in comparison with single TASK-1-/- mice [60]; effects on ventilation were not reported for the double knockouts.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Bayliss and Barrett laboratories who have contributed to work on K2P channels. We also thank Patrice Guyenet and his laboratory members for collaboration on TASK-channel contributions to central respiratory chemosensitivity. This work was supported by GM66181 and NS33583 (D.A.B.) and HL089717 (P.Q.B.) from the National Institutes of Health (www.nih.gov).

Glossary

- Central respiratory chemoreception

the homeostatic process whereby changes in CO2 and pH are sensed by neurons in the brainstem to regulate the rate and depth of ventilation and, thereby, the excretion of CO2.

- GHK-rectifying

This term refers to current-voltage relationships that adhere to assumptions as embodied in the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) current equation. For a GHK-rectifying K+ channel under physiological conditions, outward current is favored because of the asymmetrical distribution of K ions across the membrane ([K+]in > [K+]out). With symmetrical distribution of K+ ions, rectification disappears and the current-voltage relationship appears linear (ohmic).

- Hypnosis

the state in which an anesthetic causes a patient to fail to respond to verbal stimuli or an animal to fail to right itself from a supine position.

- Immobilization

to the ability of an anesthetic agent to inhibit purposeful responses to a painful stimulus.

- Rectifying

applied to voltage-dependent properties of a channel currents, ‘rectifying’ refers to the ability to pass current more effectively in one direction than the other. An inwardly rectifying channel moves greater current in the inward direction; an outwardly rectifying channel in the outward direction. A weakly rectifying or non-rectifying channel passes current equally well in both directions. These current-voltage properties often depend on experimental conditions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldstein SA, et al. Potassium leak channels and the KCNK family of two-P-domain subunits. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:175–184. doi: 10.1038/35058574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talley EM, et al. Two-pore-domain (KCNK) potassium channels: dynamic roles in neuronal function. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:46–56. doi: 10.1177/1073858402239590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesage F, Lazdunski M. Molecular and functional properties of two-pore-domain potassium channels. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F793–F801. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.5.F793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim D. Physiology and pharmacology of two-pore domain potassium channels. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005;11:2717–2736. doi: 10.2174/1381612054546824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honore E. The neuronal background K2P channels: focus on TREK1. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:251–261. doi: 10.1038/nrn2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel AJ, Honore E. Properties and modulation of mammalian 2P domain K+ channels. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01810-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathie A, Veale EL. Therapeutic potential of neuronal two-pore domain potassium-channel modulators. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2007;8:555–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein SA, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LV. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of two-P potassium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005;57:527–540. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karschin C, et al. Expression pattern in brain of TASK-1, TASK-3, and a tandem pore domain K+ channel subunit, TASK-5, associated with the central auditory nervous system. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2001;18:632–648. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fink M, et al. A neuronal two P domain K+ channel stimulated by arachidonic acid and polyunsaturated fatty acids. EMBO J. 1998;17:3297–3308. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayliss DA, et al. The TASK family: two-pore domain background K+ channels. Mol. Interv. 2003;3:205–219. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.4.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czirjak G, et al. TASK (TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ channel) is expressed in glomerulosa cells of rat adrenal cortex and inhibited by angiotensin II. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;14:863–874. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.6.0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spat A, Hunyady L. Control of aldosterone secretion: a model for convergence in cellular signaling pathways. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:489–539. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies LA, et al. TASK channel deletion in mice causes primary hyperaldosteronism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:2203–2208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heitzmann D, et al. Invalidation of TASK1 potassium channels disrupts adrenal gland zonation and mineralocorticoid homeostasis. EMBO J. 2008;27:179–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young WF. Primary aldosteronism: renaissance of a syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2007;66:607–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisgerhof M, et al. The plasma aldosterone response to angiotensin II infusion in aldosterone-producing adenoma and idiopathic hyperaldosteronism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1981;52:195–198. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-2-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wisgerhof M, et al. Increased adrenal sensitivity to angiotensin II in idiopathic hyperaldosteronism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1978;47:938–943. doi: 10.1210/jcem-47-5-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calhoun DA. Use of aldosterone antagonists in resistant hypertension. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2006;48:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajagopalan S, Pitt B. Aldosterone as a target in congestive heart failure. Med. Clin. North Am. 2003;87:441–457. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lifton RP, et al. Hereditary hypertension caused by chimaeric gene duplications and ectopic expression of aldosterone synthase. Nat. Genet. 1992;2:66–74. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayliss DA, et al. TASK-1 is a highly modulated pH-sensitive ‘leak’ K+ channel expressed in brainstem respiratory neurons. Respir. Physiol. 2001;129:159–174. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richerson GB. Serotonergic neurons as carbon dioxide sensors that maintain pH homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:449–461. doi: 10.1038/nrn1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyenet PG, et al. Retrotrapezoid nucleus and central chemoreception. J. Physiol. 2008;586:2043–2048. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.150870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Washburn CP, et al. Serotonergic raphe neurons express TASK channel transcripts and a TASK-like pH- and halothane-sensitive K+ conductance. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1256–1265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01256.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulkey DK, et al. TASK channels determine pH sensitivity in select respiratory neurons but do not contribute to central respiratory chemosensitivity. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14049–14058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4254-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckler KJ, et al. An oxygen-, acid- and anaesthetic-sensitive TASK-like background potassium channel in rat arterial chemoreceptor cells. J. Physiol. 2000;525:135–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duprat F, et al. The TASK background K2P channels: chemo- and nutrient sensors. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurney A, Manoury B. Two-pore potassium channels in the cardiovascular system. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00249-008-0326-8. DOI: 10.1007/s00249-008-0326-8 ( http://www.springerlink.com) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olschewski A, et al. Impact of TASK-1 in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2006;98:1072–1080. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000219677.12988.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicoll RA, Madison DV. General anesthetics hyperpolarize neurons in the vertebrate central nervous system. Science. 1982;217:1055–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.7112112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel AJ, et al. Inhalational anesthetics activate two-pore-domain background K+ channels. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:422–426. doi: 10.1038/8084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yost CS. Update on tandem pore (2P) domain K+ channels. Curr. Drug Targets. 2003;4:347–351. doi: 10.2174/1389450033491091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu C, et al. Potent activation of the human tandem pore domain K channel TRESK with clinical concentrations of volatile anesthetics. Anesth. Analg. 2004;99:1715–1722. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000136849.07384.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talley EM, et al. CNS distribution of members of the two-pore-domain (KCNK) potassium channel family. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7491–7505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07491.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heurteaux C, et al. TREK-1, a K+ channel involved in neuroprotection and general anesthesia. EMBO J. 2004;23:2684–2695. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerstin KM, et al. Mutation of KCNK5 or Kir3.2 potassium channels in mice does not change minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration. Anesth. Analg. 2003;96:1345–1349. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000056921.15974.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yost CS, et al. Knockout of the gene encoding the K2P channel KCNK7 does not alter volatile anesthetic sensitivity. Behav. Brain Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.05.010. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.05.010 ( www.sciencedirect.com) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linden AM, et al. TASK-3 knockout mice exhibit exaggerated nocturnal activity, impairments in cognitive functions, and reduced sensitivity to inhalation anesthetics. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;323:924–934. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linden AM, et al. The in vivo contributions of TASK-1-containing channels to the actions of inhalation anesthetics, the α2 adrenergic sedative dexmedetomidine, and cannabinoid agonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;317:615–626. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sirois JE, et al. The TASK-1 two-pore domain K+ channel is a molecular substrate for neuronal effects of inhalation anesthetics. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:6347–6354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06347.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alloui A, et al. TREK-1, a K+ channel involved in polymodal pain perception. EMBO J. 2006;25:2368–2376. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heurteaux C, et al. Deletion of the background potassium channel TREK-1 results in a depression-resistant phenotype. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:1134–1141. doi: 10.1038/nn1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meuth SG, et al. The contribution of TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+-containing channels to the function of dorsal lateral geniculate thalamocortical relay neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;69:1468–1476. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blondeau N, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are cerebral vasodilators via the TREK-1 potassium channel. Circ. Res. 2007;101:176–184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kennard LE, et al. Inhibition of the human two-pore domain potassium channel, TREK-1, by fluoxetine and its metabolite norfluoxetine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005;144:821–829. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viana F, et al. Specificity of cold thermotransduction is determined by differential ionic channel expression. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:254–260. doi: 10.1038/nn809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warth R, et al. Proximal renal tubular acidosis in TASK2 K+ channel-deficient mice reveals a mechanism for stabilizing bicarbonate transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:8215–8220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400081101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barriere H, et al. Role of TASK2 potassium channels regarding volume regulation in primary cultures of mouse proximal tubules. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003;122:177–190. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.L’Hoste S, et al. Extracellular pH alkalinization by Cl-/HCO3- exchanger is crucial for TASK2 activation by hypotonic shock in proximal cell lines from mouse kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F628–F638. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00132.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burdakov D, et al. Tandem-pore K+ channels mediate inhibition of orexin neurons by glucose. Neuron. 2006;50:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Putzke C, et al. The acid-sensitive potassium channel TASK-1 in rat cardiac muscle. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;75:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barbuti A, et al. Block of the background K+ channel TASK-1 contributes to arrhythmogenic effects of platelet-activating factor. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;282:H2024–H2030. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00956.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Terrenoire C, et al. A TREK-1-like potassium channel in atrial cells inhibited by β-adrenergic stimulation and activated by volatile anesthetics. Circ. Res. 2001;89:336–342. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.094979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meuth SG, et al. TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ channel 1 (TASK1) and TASK3 critically influence T lymphocyte effector functions. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:14559–14570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mu D, et al. Genomic amplification and oncogenic properties of the KCNK9 potassium channel gene. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voloshyna I, et al. TREK-1 is a novel molecular target in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1197–1203. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duprat F, et al. Pancreatic two P domain K+ channels TALK-1 and TALK-2 are activated by nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. J. Physiol. 2005;562:235–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dobler T, et al. TRESK two-pore-domain K+ channels constitute a significant component of background potassium currents in murine dorsal root ganglion neurones. J. Physiol. 2007;585:867–879. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trapp S, et al. A role for TASK-1 (KCNK3) channels in the chemosensory control of breathing. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8844–8850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1810-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pineyro G, Blier P. Autoregulation of serotonin neurons: role in antidepressant drug action. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:533–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]