Abstract

The cross-sectional and longitudinal relations between reasons for abstaining or limiting drinking (RALD) and abstention and alcohol consumption were examined in a sixteen-year longitudinal study (N = 489) of college students with and without a family history of alcohol problems. Results indicated that RALD based upon upbringing or religiosity were associated with increased rates of abstention, whereas RALD based upon perceived or experienced negative consequences of drinking were associated with lower rates of abstention and increased alcohol consumption among drinkers. In addition, changes in RALD over time coincided with alcohol consumption transitions. For example, abstainers who began drinking after turning 21 reported a decrease in the importance of RALD associated with loss of control and upbringing or religiosity compared to abstainers who continued to abstain after turning 21. Conversely, drinkers who began abstaining after leaving college reported an increase in the importance of RALD associated with loss of control and upbringing or religiosity compared to drinkers who continued to drink after leaving college. Examining the reciprocal influences of RALD on drinking outcomes extends previous research and may inform prevention and intervention programs among college drinkers.

Keywords: alcohol drinking attitudes, alcohol drinking patterns, cognitions, motivation, longitudinal studies

The Reciprocal Influences of Reasons for Abstaining or Limiting Drinking and Abstention Status in Adults

Addictive behavior can be conceptualized in terms of the relative strength of both impelling and inhibiting forces (Goldman, Del Boca, & Darkes, 1999; Jones, Corbin, & Fromme, 2001; Orford, 2001), though the majority of research has focused on the former (Adams & McNeil, 1991; Jones et al., 2001). Within the literature on impelling forces, both drinking motives (i.e. reasons for drinking) and positive alcohol outcome expectancies (beliefs about the positive consequences of drinking) have been shown to predict alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems (see reviews by Baer, 2002; Goldman et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2001), with drinking motives being more proximal indicators of consumption (Baer, 2002; Cooper, 1994). Parallel lines of research on inhibiting forces have examined abstention motives (i.e. reasons for not drinking) and negative outcome expectancies (beliefs about the negative consequences of drinking). While the empirical findings are mixed with regard to the association of negative alcohol expectancies and alcohol consumption (Adams & McNeil, 1991; Jones et al, 2001), relatively less is known about the association between abstention motives and alcohol consumption. Given that drinking motives have been found to be more proximal and potent predictors of drinking behavior (relative to positive outcome expectancies; Baer, 2002; Cooper, 1994), research on abstention motives may be an important complement to investigations of negative expectancies in the study of drinking-related inhibitory forces.

Beliefs about why people choose to limit their drinking or abstain from alcohol altogether have been assessed using a wide range of self-report measures that may be generically termed reasons for abstaining or limiting drinking (RALD). The intent in measuring RALD is to capture important facets of avoidance motivation with regard to drinking. Current measures of self-reported inhibitory motives are quite diverse with regard to length, item format, and content of the domains assessed. Some investigators have used a single open-ended question (Amodeo & Kurtz, 1998; Cotner, 2002; Feldman, Harvey, Holowaty, & Shortt, 1999; Knupfer & Room, 1970; Ludwig, 1972), while others have used multifactor, fixed-response questionnaires with numerous items (Adams & Nagoshi, 1999; Greenfield, Guydish, & Temple, 1989; Johnson & Cohen, 2004; Klein, 1990; Stritzke & Butt, 2001). Measures have been tailored to be appropriate for use in diverse populations (adolescents, Barnes, 1981; young adults, Adams & Nagoshi, 1999; Greenfield et al., 1989; adults, Graham, 1998; abstainers, Johnson, Schwitters, Wilson, Nagoshi, & McClearn, 1985; Klein, 1990; alcoholics, Amodeo, Kurtz, & Cutter, 1992). Investigators have used a variety of techniques, including factor analytic methods, to identify between 1 and 6 candidate domains of RALD (Barnes, 1981; Greenfield et al., 1989; Hilton, 1986; Johnson & Cohen, 2004; Klein, 1990; Knupfer & Room, 1970; Maggs & Schulenberg, 1998; Stritzke & Butt, 2001; Wood, Nagoshi, & Dennis, 1992). To date, no measure of RALD has emerged as a standard in the field. A failure to achieve consensus regarding the measurement of RALD may have contributed to the underdevelopment of RALD research, relative to the more mature literatures on motives for drinking and alcohol outcome expectancies.

Despite variability in measurement, existing evidence suggests self-reported RALD are meaningfully related to drinking behavior. However, this relation is complex. In general, studies using measures comprising one or two RALD factors find negative associations with alcohol use (Barnes, 1981; Maggs & Schulenberg, 1998; Nagoshi, Nakata, Sasano, & Wood, 1994; Wood et al., 1992). In these studies, endorsement of more or stronger RALD was associated with less drinking (Chassin & Barrera, 1993; Maggs & Schulenberg, 1998; Nagoshi et al., 1994; Reeves & Draper, 1984; Stritzke & Butt, 2001). However, studies that differentiate individual RALD into three or more factors find both positive and negative relations with alcohol outcomes. The distinguishing “extra” factor(s) in these studies typically reflects negative consequences of drinking that may be especially relevant to persons with extensive drinking experience. RALD domains such as religious/moral considerations, a desire to maintain personal control, and upbringing are negatively associated with drinking while concerns regarding expense and desire to avoid adverse consequences are positively associated with drinking rates (Collins, Koutsky, & Izzo, 2000; Greenfield et al., 1989; Slicker, 1997).

The distinct positive and negative associations between RALD factors and alcohol consumption measures may reflect distinct pathways of formation and development of RALD domains. For example, people who strongly endorse RALD such as, “it’s against my religion,” and “I was brought up not to drink,” are likely to have acquired these motives at an early age. Thus, they may experience delayed exposure to alcohol consumption or no exposure at all, leading to a negative relation between these particular RALD (high endorsement) and current alcohol consumption (low). In contrast, problem drinkers may initiate drinking early or at a normative age, and through experimentation, experience first-hand the negative consequences of drinking. Thus, they may be especially likely to endorse RALD items tapping negative drinking consequences. This would result in positive associations between negative consequences RALD and alcohol consumption. Empirical evidence indirectly supports this developmental hypothesis: the associations between RALD and drinking are simpler among adolescents who are in the early stages of alcohol initiation as compared to samples of young adults for whom drinking is normative and experience with alcohol consumption is more extensive (compare Chassin & Barrera, 1993; Maggs & Schulenberg, 1998 to Collins, Koutsky, Morsheimer, & MacLean, 2001; Greenfield et al., 1989). It is unclear whether endorsement of negative consequences RALD reflects a causal process whereby consequences are punishing and reduce future drinking or merely serves as a marker or proxy for alcohol-related problems (for example, as an indicator of unsuccessful attempts at cutting back).

Alcohol abstainers are an important subpopulation for research on RALD because the avoidance of alcohol should influence the development of some RALD and reflect some RALD domains. Existing evidence, although limited, does suggest that abstainers report different RALD than do drinkers (Slicker, 1997). In addition to being a potentially formative influence on RALD, abstention status is clearly an important outcome that should be a focus of study in RALD research. To date, abstainers have not been consistently included in RALD investigations (cf. Adams & Nagoshi, 1999; Collins et al., 2000; Collins et al., 2001; Greenfield et al., 1989; Wood et al., 1992).

Abstention status is not static; individuals may move in and out of abstention over the course of their drinking careers. Examining changes in abstention status during developmentally important transitions may speak to the construct validity of RALD. One such developmental transition occurs when young adults attain legal drinking status at age 21. Examining changes in RALD among young adults who begin drinking only after turning 21 may provide information about the sensitivity of RALD to changes in drinking experience (from abstainer to drinker) and drinking context (e.g., from illegal to legal). Another important transition in which abstention status is known to change is the transition from college to more adult roles such as career employment, marriage, and childbirth (Gotham, Sher, & Wood, 1997). Examining changes in RALD among young adults who stop drinking after leaving college may provide further information about the construct validity of RALD and responsiveness to change in drinking status in the other direction (from drinker to abstainer). Although there are several longitudinal studies of RALD in the literature, only one study has demonstrated prospective prediction of drinking behavior from RALD (in adolescents; Chassin & Barrera, 1993), and no studies have examined the association of RALD and drinking status across noteworthy developmental transitions in young adulthood. If RALD do not influence future drinking or fail to respond to important changes in drinking status, this would question the value of RALD assessment.

The majority of studies that have examined sex differences in RALD endorsement have reported no significant differences (Feldman et al., 1999; Klein, 1990; Nagoshi et al., 1994; Stritzke & Butt, 2001; Wood et al., 1992). However, several studies have found some differences between males and females (Greenfield et al, 1989; Moore & Weiss, 1995) and these exceptions may prove informative for understanding the strong sex differences in problem drinking outcomes (Muthen & Muthen, 2000). Therefore we have included analyses examining possible sex differences among RALD in this study.

RALD have been shown to be related to familial alcohol problems (Hesselbrock, O’Brien, Weinstein, & Carter-Menendez, 1987; Klein, 1990). Evidence suggests that participants with a family history of alcohol problems endorse some RALD items (e.g. “not wanting to lose control” and “I am afraid that I might develop an alcohol problem if I drink”) more frequently than participants without a family history (Chassin & Barrera, 1993; Klein, 1990). Different RALD profiles among children of alcoholics (COAs) may arise from experiences with alcoholism in the home or increased personal rates of heavy drinking arising from inherited or learned risk processes. COAs are known to be at elevated risk for alcohol-related problems (Sher, 1991), therefore exploring RALD among those with a family history of alcohol problems may be informative for understanding mechanisms or correlates of this risk and for probing influences on RALD formation.

Using data from a 16-year, prospective study of early adult drinking (N = 489) that oversampled participants with a family history of alcohol problems (51%), we sought to extend the current body of literature on RALD. Because recent studies lack consistency in the measurement of RALD and the number of RALD factors examined may impact the direction of relations between RALD and alcohol consumption, we hypothesized that a factor structure with three or more factors would result in bidirectional relations to alcohol consumption.

The present study examines the factor structure of 10 RALD items assessed at seven different times, beginning at age 18 and continuing through age 34. Using the resulting factor structure, a series of analyses were conducted to explore the relations between RALD and abstention status, including specific analyses focused on informative developmental transitions (turning 21 and leaving college) and the influence of sex and family history of alcohol problems. We hypothesized that changes in drinking status would result in corresponding changes in RALD. Finally, no study to date has examined whether changes in RALD actually influence future abstention status among adults. Therefore, the present study explored the reciprocal influences between RALD and abstention status. We expected that RALD would prospectively influence future abstention status. In addition, we hypothesized that abstention status might also prospectively influence RALD as reciprocal influence has been demonstrated in studies of alcohol outcome expectancies (see Smith, Goldman, Greenbaum, & Christiansen, 1995; Sher, Wood, Wood, & Raskin, 1996).

Methods

Participants

Data were collected as part of a longitudinal study of alcohol use and health behaviors among college students. Participants were recruited during their freshmen year at a large Midwestern university, and students with a paternal history of alcoholism were oversampled. The final sample included 489 college freshmen of whom 51% were family history positive (see Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991, for more detail on procedure, sampling scheme, and a description of our two-stage assessment of family history). The sample had an average age of 18.5 (SD = 0.97) at the time of recruitment, was 46% male and 90% Caucasian. Six subsequent self-report assessments were administered 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 6 years, 10 years, and 16 years after baseline. Retention across all 7 waves was high, with 341 (70%) participants completing all 7 assessments. Analyses examining whether attrition from the study (116 of the wave 1 participants did not participate in wave 7) was related to any of the variables of interest in our manuscript suggested that males were more likely than females to be lost at follow-up (OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.08, 2.51); all other variables were not significant.

Measures

Demographic variables including sex and family history of alcohol problems were assessed at baseline. For all analyses, sex was coded 0 for men and 1 for women and family history of alcohol problems was coded 0 if absent and 1 if present.

A 10-item self-report measure of RALD was administered at all seven waves of data collection (instructions and items are reproduced in the Appendix). Participants rated their level of agreement that the reason was important for limiting drinking or not drinking on a four-point Likert scale with 0 indicating strongly disagree and 3 indicating strongly agree. Based on the resulting factor structure, composite variables of each factor of RALD were computed by averaging across items. These mean composite variables were used in all analyses with the exception of the cross-lagged panel model which utilized latent variables for each factor (as described below).

Frequency and typical quantity of alcohol consumption was assessed at each time point using standard alcohol frequency and quantity items asking about the number of drinking occasions and the typical number of drinks consumed per occasion in the past 12 months. Heavy episodic drinking, or binge drinking, was assessed using a measure of the frequency of drinking 5 or more drinks on one occasion in the past 12 months. When this study began in 1987 these items were considered standard despite not being part of a formalized measure. The items are now part of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993).

Abstention was defined as reporting less than 6 drinking occasions in the past 12 months and reporting never drinking 5 or more drinks on one occasion in the past 12 months. This definition of abstention was chosen because of the relatively low rates of absolute abstention in this sample (7%, 7%, 5%, 6%, 6%, 9%, 10% for waves 1–7 respectively1). Thus, we attempted to capture those participants who might only be drinking on special occasions and who otherwise abstain and may be more similar to abstainers on our measure of RALD, which includes both abstention and limiting drinking, than to regular drinkers. Further, we felt it was important to exclude those infrequent drinkers who reported “binge-like” episodes involving more than 5 drinks on an occasion. We will refer to the resulting group as “virtual abstainers” to distinguish them from other reports examining absolute abstainers in the literature (rates of virtual abstention: 13%, 13%, 14%, 12%, 14%, 20%, 23% for waves 1–7 respectively).

Analysis

Exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were conducted on the 10 reasons for not drinking at each wave of assessment using iterated principal factors method with Promax rotation. To test the fit of the factor structure in later waves, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA; specifying the structure obtained using Wave 1 data) were conducted on waves 2–7. EFAs were conducted at each wave within subgroups of interest to determine whether the factor structure was invariant across sex and family history of alcohol problems status. In addition, factor loading invariance was across waves was tested using Mplus software (Muthen, B. & Muthen, 1998–2007). For all latent variable analyses, we used the RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error Approximation) as an index of model fit (see MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996). To assess the significance of change in model fit across nested models we used χ2 change tests or an adaptation of the χ2 change test when our models contained categorical variables (Muthen, L. & Muthen, 1998–2007).

To describe the bivariate cross-sectional relations among RALD and abstention status, a series of logistic regression analyses were conducted. For each year of the study, individual RALD factors were used to predict virtual abstention. To describe the cross-sectional relations among RALD and alcohol consumption among drinkers, correlations between RALD and the average number of drinks consumed per week were calculated for each year of the study (excluding virtual abstainers).

To examine longitudinal patterns of abstention, a dichotomous variable was created based on our definition of virtual abstention, described above, for each participant at each wave of data. Participants were assigned a score of (1) if they met our criteria for virtual abstention and all other participants were considered drinkers and assigned a score of (0). Each participant was categorized into logical groups2 based on their pattern of zeros and ones across the study waves, ignoring missing values. Participants who reported drinking at every wave in which they participated were categorized as drinkers (n = 313, 76%); participants who reported drinking at the first wave of data collection and reported virtual abstention at a subsequent wave in which they participated (and all others following that transition) were categorized as drink to abstain (n = 56, 14%); participants who reported virtual abstention at Wave 1 and drinking at a subsequent wave in which they participated (but not necessarily at Waves 6 or 7) were categorized as abstain to drink (n = 18, 4%); and finally participants who reported virtual abstention at every wave in which they participated were categorized as abstainers (n = 25, 6%). In order to describe general differences between abstainers, abstain to drink, drink to abstain, and drinkers over time, mean levels of RALD were computed for each group. In addition, between-subject and within-subject results from repeated-measures ANOVAs are reported. Within the ANOVA, three orthogonal contrasts were conducted: Abstain vs. Abstain to Drink, Drink vs. Drink to Abstain, and Abstain and Abstain to Drink vs. Drink and Drink to Abstain (note that this last contrast groups together those whose initial status was the same).

In order to examine potential mean-level and moderating effects of sex and family history on RALD, between-subject and within-subject results from repeated measures ANOVAs are reported separately for sex and family history. Sex and family history variables are also included in the specific transition analyses and prospective influence models described below.

In order to describe changes in RALD during two important developmental transitions, turning 21 and leaving college, a series of repeated measures ANOVA were conducted. Participants were divided according to the pattern of abstention and drinking prior to and immediately following their 21st birthday into four groups: those who abstained both pre and post-age 21 (n = 38, 9%), those who drank both pre and post-age 21 (n = 372, 83%), those who abstained pre-age 21 and drank post-age 21 (n = 24, 5%), and those who drank pre-age 21 and abstained post-age 21 (n = 12, 3%). Mean change in RALD factors were compared among the groups across this transition. A similar technique was used to examine changes in RALD across the transition out of college. Participants were divided based on their abstention and drinking status at Wave 4 (senior year of college) and Wave 5 (3 years post-college) into four groups: those who abstained during their last year of college and reported abstaining three years later (n = 34, 8%), those who reported drinking during their last year of college and again three years later (n = 364, 82%), those who reported abstaining during their last year of college and reported drinking three years later (n = 19, 4%), and those who reported drinking during their last year of college and reported abstaining three years later (n = 29, 7%). Again mean change in RALD factors were compared among the groups across this transition.

Finally, in order to more fully examine the potential influence of RALD on future changes in abstention status and vice versa, an auto-regressive, cross-lagged path analysis was conducted using Mplus (Muthen, B. & Muthen, 1998–2007). This analysis allows for interpretation of the prospective directional influences of RALD and abstention status upon one another in addition to estimates of the stability of RALD and abstention. In order to create relatively equal spacing between measurements, Waves 2 and 3 were dropped from this analysis, resulting in four transition periods: first year of college to fourth year of college, fourth year of college to three years post-college, three years post-college to seven years post-college, and seven years post-college to 12 years post-college (descriptions of transition periods correspond to normative patterns for traditional four-year graduates, however it should be noted that not all participants stayed in college for four years and some stayed longer).

Missing Data

For cross-sectional analyses conducted using Mplus software (CFAs and measurement invariance testing by sex and family history) and all analyses conducted using SAS software (EFAs, regression and correlation analyses, and ANOVAs), listwise deletion was used, thus the number of participants included in a particular analysis varies depending on which waves the variables were from. For longitudinal analyses conducted using Mplus (measurement invariance testing over time and the cross-lagged panel model), all available data were modeled. Mplus allows for the estimation of models with missing data that is either missing completely at random (MCAR) or missing at random (MAR) using maximum likelihood estimation (Muthen, L. & Muthen, 1998–2007). Attrition analyses examining differences between participants with incomplete data at Wave 7 from those with complete data on variables of interest in this study suggested that only sex was significantly associated with attrition from the study. There were no significant differences on RALD factors, virtual abstention status, or family history status. The number of participants included in each analysis is provided in text and/or in tables and figures.

Results

Factor Structure

Based on the pattern of eigenvalues for each factor and interpretability of resulting factors, we determined that a three-factor model was appropriate for 9 of the 10 RALD items. Results from exploratory factor analyses at each wave resulted in a consistent pattern of factor loadings across 9 of the 10 RALD (Table 1), the “unhealthy” item was dropped due to cross-loading on multiple factors. Specifically, beliefs that one would become rude or obnoxious, lose control, become alcoholic, and get into trouble were consistently identified as factor 1, which we labeled Loss of Control. Expense, become ill (also significantly loading on factor 1 at year 4 only), and interfere with responsibilities consistently loaded on factor 2, labeled Adverse Consequences; and against religion and friends against drinking composed factor 3, labeled Convictions. Inter-factor correlations across seven waves ranged from .50 to .57 between factors 1 and 2, from .33 to .51 between factors 1 and 3, and from .16 to .35 between factors 2 and 3. Confirmatory factor analyses conducted on waves 2–7 resulted in adequate fit of this factor structure (RMSEA ranged from .035 to .068; ns for CFAs are the same as those for EFAs presented in Table 1).

Table 1.

Factor Loadings from Exploratory Factor Analyses at Each Study Year

| Loss of Control | Adverse Consequences | Convictions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Be obnoxious |

Lose control |

Become alcoholic |

Get into trouble |

Expen- sive |

Become ill |

Interfere with Respons- ibilities |

Friends against |

Religion against |

|

| Year 1 (n = 484) | |||||||||

| Factor 1 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

| Factor 2 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.18 | −0.06 |

| Factor 3 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.20 | 0.59 | 0.50 |

| Year 2 (n = 480) | |||||||||

| Factor 1 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.32 |

| Factor 2 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.25 | −0.04 |

| Factor 3 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.46 |

| Year 3 (n = 469) | |||||||||

| Factor 1 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| Factor 2 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 0.18 | −0.04 |

| Factor 3 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.61 |

| Year 4 (n = 465) | |||||||||

| Factor 1 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.23 |

| Factor 2 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.21 | −0.01 |

| Factor 3 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.75 | 0.49 |

| Year 7 (n = 451) | |||||||||

| Factor 1 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| Factor 2 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.18 | −0.05 |

| Factor 3 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.59 | 0.63 |

| Year 11 (n = 396) | |||||||||

| Factor 1 | 0.60 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.12 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| Factor 2 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.20 | 0.02 |

| Factor 3 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.72 | 0.59 |

| Year 16 (n = 373) | |||||||||

| Factor 1 | 0.60 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Factor 2 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.84 | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| Factor 3 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.52 |

Note. Bolded values indicate the highest loading for each item at each study year. Factor loadings were taken from the first three factors extracted.

Based on the resulting three-factor structure, we expected that Convictions and Loss of Control RALD would be positively associated with virtual abstention and negatively associated with alcohol consumption as found in the literature when one or two factors are identified (Chassin & Barrera, 1993; Maggs & Schulenberg, 1998; Nagoshi et al., 1994; Reeves & Draper, 1984; Stritzke & Butt, 2001). With the third factor, Adverse Consequences, we expected to find a negative association with virtual abstention and positive associations with alcohol consumption. This pattern of results would reflect the bi-directional associations between RALD and alcohol consumption measures as found in the literature when three or more factors are identified (Collins et al., 2001; Greenfield et al., 1989).

Results from EFAs at each wave in males (n ranged from 229 at year 1 to 166 at year 17), females (n ranged from 255 at year 1 to 207 at year 17), family history positive (n ranged from 247 at year 1 to 190 at year 17) and family history negative (n ranged from 235 at year 1 to 181 at year 17) participants suggest that the factor structure is generally invariant across sex and family history of alcohol problems status (data not shown). Factor structure invariance across sex and family history status is necessary in order to examine and interpret mean level differences among subgroups. A test of factor loading invariance across time suggested that factor loadings could be held constant for each factor across the waves without a significant decrement in fit (χ2 change = 45.02, 36 df; not significant, p = .144; n = 489). Factor loading invariance across time is necessary in order to examine the reciprocal influences of RALD and abstention status in a prospective, latent variable framework.

Cross-sectional Relations

Loss of Control RALD were associated with increased odds of abstaining at years 1 through 7, while Adverse Consequences RALD were not associated with abstaining at any year (Table 2). Convictions RALD were associated with increased odds of abstaining at all study years (Table 2). Ancillary analyses examining differences between absolute and virtual abstainers on RALD suggested that there were significant differences on two of the three resulting RALD factors. These results suggest that our findings may not be directly comparable to those on absolute abstainers, as absolute abstainers had higher levels of both Loss of Control and Convictions RALD compared to virtual abstainers (data not shown). Among drinkers, Loss of Control RALD were associated with increased consumption at years 4 and 11, while Convictions RALD were associated with decreased consumption only at year 7 (Table 2). Results suggest that Convictions RALD may be critical in determining whether or not someone chooses to drink alcohol, however, among those who drink Loss of Control RALD seems to have the highest association with the amount consumed.

Table 2.

Bivariate, Cross-Sectional Relations between RALD Factors and Virtual Abstention Status and Typical Weekly Alcohol Consumption Among Drinkers†

| Loss of Control RALD | Adverse Consequences RALD | Convictions RALD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Abstention Status | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Year 1 (n = 486) | 2.0 (1.5, 2.9)* | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 3.0 (2.2, 4.1)* |

| Year 2 (n = 480–481) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4)* | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 2.4 (1.8, 3.3)* |

| Year 3 (n = 469) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4)* | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | 3.0 (2.2, 4.2)* |

| Year 4 (n = 466–468) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.6)* | 1.0 (0.7, 1.3) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.6)* |

| Year 7 (n = 451) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3)* | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 2.8 (1.9, 3.9)* |

| Year 11 (n = 396) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 2.7 (1.9, 3.8)* |

| Year 16 (n = 373) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 2.4 (1.7, 3.4)* |

| Weekly Alcohol Consumption† | r (p) | ||

| Year 1 (n = 423) | .00 (.922) | .05 (.271) | −.08 (.098) |

| Year 2 (n = 419–420) | .02 (.561) | .09 (.080) | −.06 (.249) |

| Year 3 (n = 405) | .07 (.147) | .01 (.884) | −.08 (.094) |

| Year 4 (n = 410–412) | .15 (.002)* | .09 (.053) | −.03 (.587) |

| Year 7 (n = 387) | .05 (.342) | −.04 (.413) | −.10 (.041)* |

| Year 11 (n = 315) | .24 (.000)* | .06 (.271) | .05 (.332) |

| Year 16 (n = 287) | .11 (.052) | .00 (.956) | −.06 (.352) |

Note. Virtual Abstainers were omitted from the correlation analyses on typical weekly alcohol consumption.

p < .05.

Mean Levels of RALD by Abstention Groups

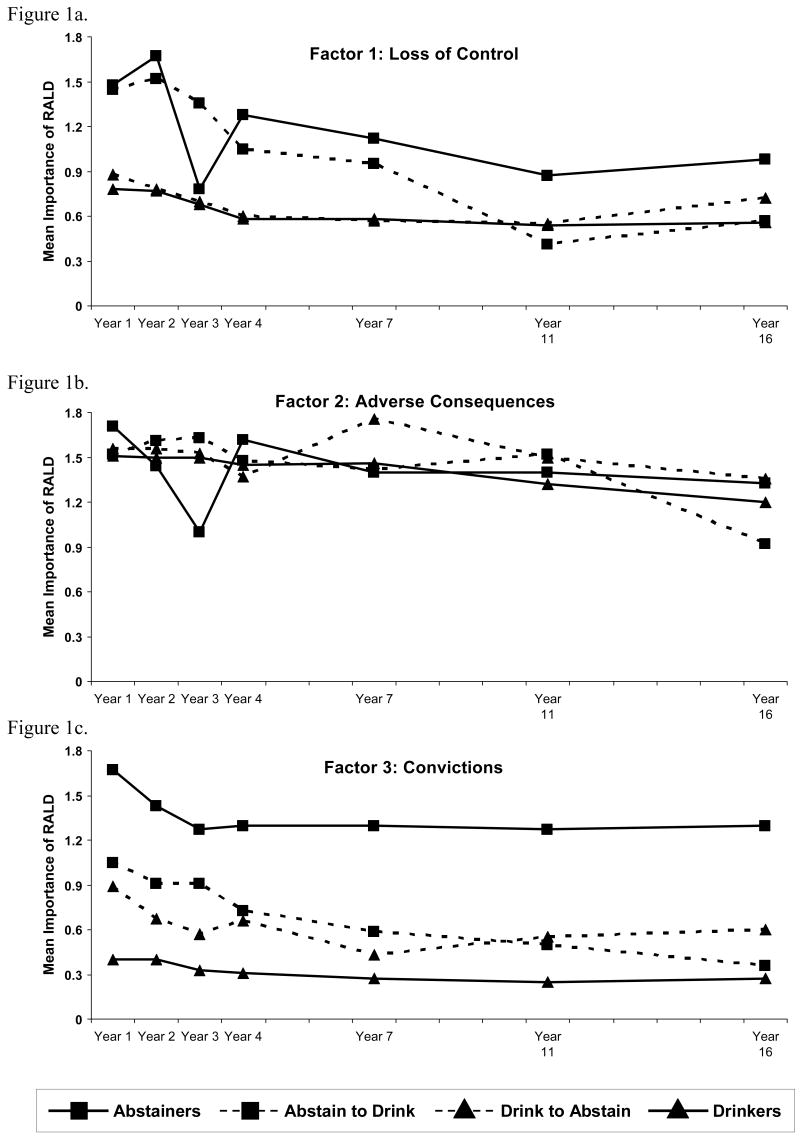

For Loss of Control RALD, a significant time by abstention group interaction was found (F(18, 1656) = 2.15, p = .003). Follow-up contrasts suggest that time effects are significant for Abstain vs. Abstain to Drink (F(6, 1656) = 3.04, p = .006) and for Abstain and Abstain to Drink vs. Drink and Drink to Abstain (F(6, 1656) = 3.21, p = .004). Profile contrasts indicated that for Abstain vs. Abstain to Drink, change from year 3 to year 4 was significantly different (F(1, 276) = 6.66, p = .010; see Figure 1a). This is consistent with the hypothesis that students who start out abstaining, but later begin drinking, are likely to do so at age 21, resulting in a contemporaneous change in RALD. Thus, as abstainers begin drinking, we see a change in the importance of Loss of Control RALD, specifically these reasons become less important (for more focused analyses on this transition see below). Profile contrasts indicated that for Abstain and Abstain to Drink vs. Drink and Drink to Abstain, change from year 7 to year 11 was significantly different (F(1, 276) = 7.24, p = .008). It appears that this effect is driven by the Abstain to Drink group that reports a decrease in importance of Loss of Control RALD over this period compared to the groups who started out drinking and have fairly constant levels of these reasons after year 4 (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a, b, and c. Mean levels of RALD by abstention group (n = 279–280).

For Adverse Consequences RALD, no significant between-subject or within-subject effects were found for abstention groups (Figure 1b).

For Convictions RALD, a significant between-subject effect was found for abstention group (F(3, 275) = 36.46, p < .001), however abstention group did not interact with time (F(18, 1650) = 1.07, p = .381). This suggests that although there are overall mean differences in Convictions RALD across abstention groups, the groups are changing similarly over time (see Figure 1c). Specific abstention group contrasts of the between-subject effect indicate significant overall differences between Abstain vs. Abstain to Drink (F(1, 275) = 15.86, p < .001), Drink vs. Drink to Abstain (F(1, 275) = 19.12, p < .001), and Abstain and Abstain to Drink vs. Drink and Drink to Abstain (F(1, 275) = 42.16, p < .001).

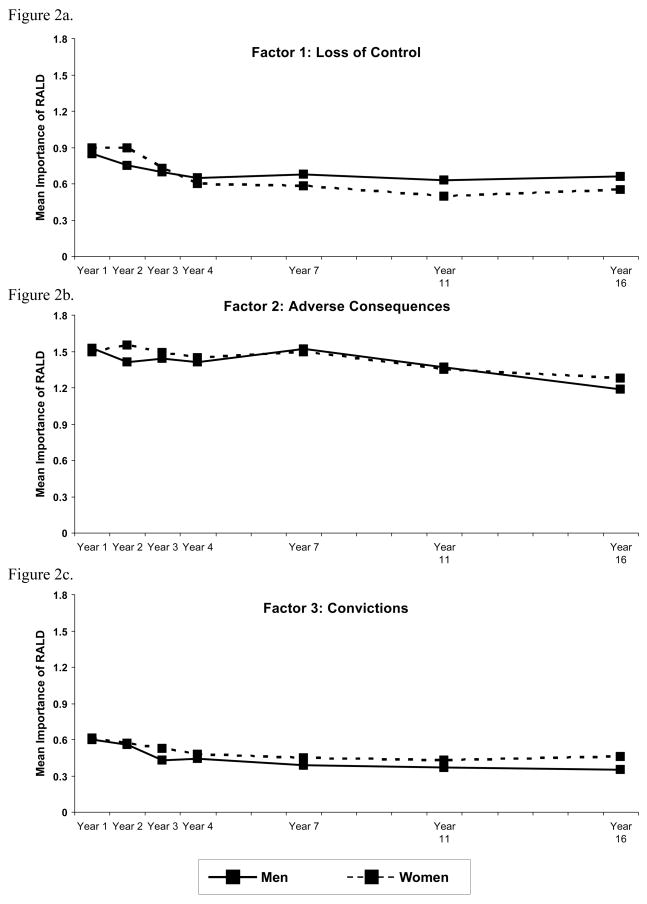

Mean Levels of RALD by Sex

For Loss of Control RALD, a significant time by sex interaction was found (F(6, 2034) = 2.88, p = .009; see Figure 2a), with women starting out slightly higher than males at years 1 and 2, decreasing more over time, and ending up slightly lower than males at year 16 (when participants were 34 years old on average). There were no significant differences between subject effects or interactions between sex and time for Adverse Consequences and Convictions RALD (see Figures 2b and 2c). Due to the significant effects for Loss of Control RALD, sex should not be ignored when examining RALD in this age group. For this reason, we have included sex as a covariate in both of the transition analyses and the final reciprocal-influence models reported below.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a, b, and c. Mean levels of RALD by sex (n = 339–341).

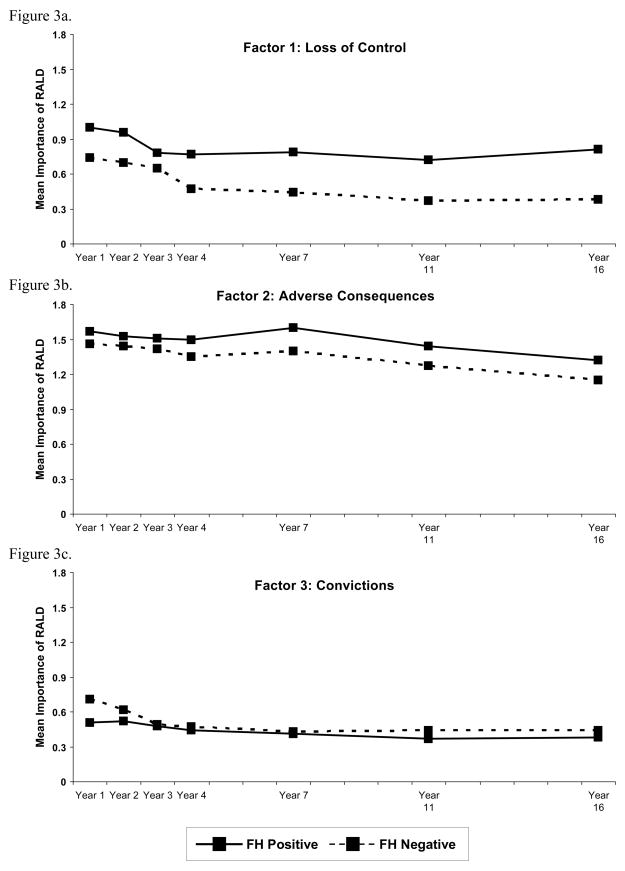

Mean Levels of RALD by Family History

For Loss of Control RALD, a significant time by family history interaction was found (F(6, 2028) = 2.56, p = .012; see Figure 3a). This suggests that change in Loss of Control RALD over time is different for participants who report a family history of alcohol problems compared to those who do not. Specifically, participants with a family history of alcohol problems do not show a decrease in Loss of Control RALD after year 3, while those without a family history of alcohol problems do. Individuals with a family history of alcohol problems endorse higher levels of importance for Adverse Consequences RALD compared to those without a family history (F(1, 338) = 5.47, p = .020; see Figure 3b). There were no significant between subject effects or interactions between family history and time for Convictions RALD (Figure 3c). Overall, these findings suggest that family history of alcohol problems may be an important moderator of RALD and should not be ignored when examining RALD in this age group. For this reason, we have included family history status as a covariate in both of the transition analyses and the final reciprocal-influence models reported below.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a, b, and c. Mean levels of RALD by family history of alcohol problems (n = 338–340).

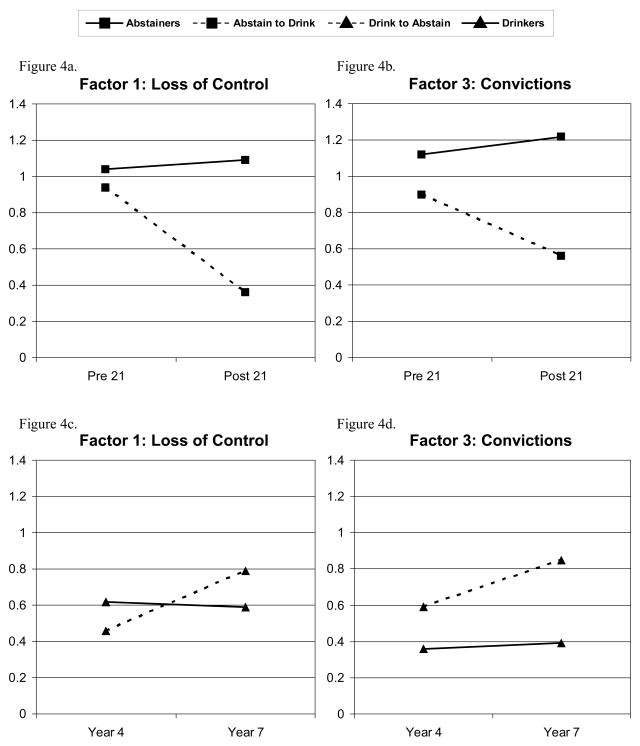

Transition to Age 21

A significant within-subject interaction between time and the contrast comparing Abstain vs. Abstain to Drink was found for both Loss of Control (F(1, 438) = 9.82, p = .002; n = 444) and Convictions RALD (F(1, 437) = 6.01, p = .025; n = 443) with participants who begin drinking after their 21st birthday showing a corresponding reduction in both Loss of Control (Figure 4a) and Convictions (Figure 4b) RALD when compared to participants who continue to abstain after turning 21. There were no significant effects associated with Adverse Consequences RALD. Sex and family history status were not significant moderators in these analyses.

Figure 4.

Figure 4a, b, c, and d. Adjusted Mean Levels of RALD Across the Transition to Age 21 (n = 443–444) for Abstainers and Abstainers who Begin Drinking After Their 21st Birthday and Across the Transition from College to Post-College (n = 443–445) for Drinkers and Drinkers who Begin Abstaining After Leaving College.

Transition Out of College

A significant within-subject interaction between time and the contrast comparing Drink vs. Drink to Abstain was found for Loss of Control RALD (F(1, 439) = 6.03, p = .015; n = 445) and a marginally significant interaction was found for Convictions RALD (F(1, 437) = 3.77, p = .053; n = 443). These interactions indicate that participants who begin abstaining after leaving college show a corresponding increase in both Loss of Control (Figure 4c) and Convictions (Figure 4d) RALD when compared to participants who continue to drink after college. There were no significant effects associated with Adverse Consequences RALD. Sex and family history status were not significant moderators in these analyses.

Model Building

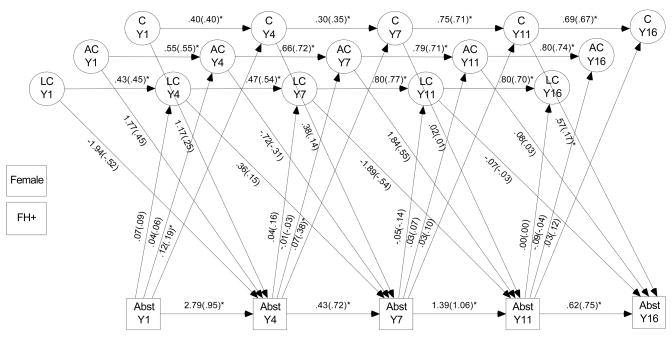

In order to test the reciprocal influences of RALD and abstention status over time, we began by testing our factor structure. The longitudinal measurement model included intra-wave correlations among RALD factors and correlations between individual item errors over time. The time-invariant longitudinal measurement model with five waves (Years 1, 4, 7, 11, and 16) fit the data well (RMSEA = .044; n = 489). Next we incorporated abstention status into the model. Recent research suggests that latent variable modeling with dichotomous outcomes can be problematic because of restrictions on the form of the assumed latent response variable (Cho, Wood, & Heath, 2009; Millsap & Yun-Tein, 2004). Therefore, we used a three-level ordinal variable to indicate abstention status (0 = drinker, 1 = virtual abstainer, 2 = absolute abstainer; n for drinkers = 423, 412, 387, 315, and 287 at years 1, 4, 7, 11, and 16 respectively; n for virtual abstainers = 28, 30, 35, 52, and 50 at years 1, 4, 7, 11, and 16 respectively; n for absolute abstainers = 35, 26, 29, 36, and 36 at years 1, 4, 7, 11, and 16 respectively). Abstention status was incorporated into the measurement model by specifying cross-sectional correlations between abstention and RALD at each wave. In addition, this model also included autoregressive paths for RALD and abstention status to assess stability over time. The autoregressive model with cross-sectional correlations had adequate fit (RMSEA = .054; n = 489). Next we included the crosslagged paths from RALD to abstention and vice versa to assess reciprocal prospective influences. The crosslagged model fit significantly better than the autoregressive, cross-sectional model (χ2 change = 24.68, 11 df, p = .010) and had adequate fit to the data (RMSEA = .054; n = 489). Finally, we included sex and family history as covariates in the crosslagged model by including paths from sex and family history to each RALD factor at each wave and abstention status at each wave. This final model had adequate fit to the data (RMSEA = .057; n = 487). A simplified diagram of the final model is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Simplified SEM model with auto-regressive and cross-lagged paths between RALD factors and abstention status (n = 487). A number of variables and paths that are included in this model are NOT shown for presentation purposes. Variables omitted from this figure include each of the individual RALD items at each time point and their error latent variables. Paths omitted from the figure include: correlations among individual item errors over time; correlations among RALD factors within wave; correlations among RALD and abstention within wave; and regression paths from the covariates (sex and family history status) to each RALD factor and each indicator of abstention status. LC = Loss of Control RALD; AC = Adverse Consequences RALD; C = Convictions RALD; Abst = Abstention Status (0 = drinker; 1 = virtual abstainer; 2 = absolute abstainer); FH+ = family history status is positive for history of alcohol problems. * p < .05.

Reciprocal Influences

Results from the final model indicate that above and beyond the auto-regressive and cross-sectional relations, there appear to be very few cross-lagged influences of RALD factors and abstention status in this high-risk sample (Figure 5). There were no significant cross-lagged relations between Loss of Control or Adverse Consequences RALD and abstention status across the study period. For Convictions RALD, abstention status at years 1 and 4 predicted increased importance of Convictions RALD at years 4 and 7 respectively (standardized path coefficient year 1 to year 4 = .19, p = .020; year 4 to year 7 = .38, p = .020; Figure 5). Year 11 importance of Convictions RALD significantly predicted an increase in abstention at year 16 (standardized path coefficient = .17, p = .039; Figure 5).

We found significant cross-sectional correlations between Loss of Control RALD and abstention status at years 1 and 7 (standardized path coefficients = .33 and .33, respectively, ps < .05), and between Convictions RALD and abstention status at year 1 (standardized path coefficient = .46, p < .001; cross-sectional correlations are not shown in Figure 5). As expected all auto-regressive paths were significant among the factors and abstention status (ps < .05; Figure 5). In addition, all of the RALD factors were significantly correlated within year (ranging from .57 to .90 between Loss of Control and Adverse Consequences RALD, from .24 to .56 between Loss of Control and Convictions RALD, and from .24 to .49 between Adverse Consequences and Convictions RALD; all ps < .05; inter-factor correlations are not shown in Figure 5).

Potential Effects of Sex and Family History

With regard to sex and family history in our final model, sex was not a significant predictor of RALD or abstention status at any wave (results not provided; paths not shown in Figure 5). Family history significantly predicted Loss of Control RALD at years 1, 4, and 7 (standardized path coefficients = .20, .11, and .18 respectively, all ps < .05; paths not shown in Figure 5), consistent with results from the repeated measures ANOVA presented above. Family history also significantly predicted Adverse Consequences RALD, but only at year 5 (standardized path coefficient = .14, p = .031). Family history was not related to Convictions RALD or abstention status at any wave of data in the final path model (results not provided; paths not shown in Figure 5).

Discussion

Given the previous focus in the literature on RALD as a means of gaining insight for prevention and intervention strategies, it seems critical to establish that RALD do in fact influence future alcohol consumption patterns. Consistent with prior research, Convictions RALD were positively related to abstention status; Loss of Control RALD was also positively related to abstention status (as reported in cross-sectional analyses, Table 2). Surprisingly there were very few significant associations between RALD factors and average weekly alcohol consumption among drinkers and these correlations were modest in magnitude (Table 2). These cross-sectional results are somewhat inconsistent with the literature in terms of associations with alcohol consumption and, to some degree, abstention status. This is most likely due to the differences between our factor structure and those of other measures of RALD (i.e., Greenfield et al, 1989).

The Structure of Reasons for Abstaining or Limiting Drinking

The three-factor structure (i.e., Convictions, Consequences, and Loss of Control) found in this study was time-invariant across the 7 waves of data collection, spanning 17 years. In addition, the factor structure was generally invariant across sex and family history of alcohol problems status. As suggested by previous literature, results from this study suggest that it is important to assess several domains of RALD in order to get at the full and complex relations between RALD and drinking-related outcomes. Results also suggest that RALD is not a static construct as indicated by significant changes across the study period related to abstention status, sex, and family history of alcohol problems (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Importantly, these changes and their relation to alcohol-related outcomes offer evidence for the construct validity of RALD as assessed by a brief (9-item) measure. Specifically, changes in Loss of Control and Convictions RALD over the two developmental transitions examined in this study suggest that RALD are dynamic and meaningfully related to alcohol-related outcomes (Figure 4).

The Dynamic Nature of RALD

Results from the analyses on the transition to legal drinking status suggested that as people become drinkers they report contemporaneous decreases in Loss of Control and Convictions RALD, while those who maintain their abstention status after turning 21 remain stable and high on all three RALD factors (Figures 4a and 4b). Although the reasons for these concurrent changes are unknown, there are several possible explanations for these findings. It is possible that we see a decrease in Convictions RALD during this transition due to religious proscriptions on alcohol that do not include moderate levels of consumption that are legal; it may also be that friends, who may also be turning 21, are not strongly against legal consumption. Both of these explanations assume that the instrumental change is the attainment of legal-drinking status, however it may be that this change is due to distance from the family environment that likely influenced their convictions about drinking. Thus as college students individuate from their families of origin they are less likely to maintain strong convictions about the unacceptability of drinking alcohol. One possible explanation of the concurrent decrease in Loss of Control RALD is that the threat of legal trouble is no longer as relevant to those who are of legal drinking age. Another possibility is that as first-hand experience with drinking accumulates and people discover that they can regulate their drinking, fears about losing control abate.

Results on the transition out of college suggest that as drinkers start to abstain they experience increases in Loss of Control and Convictions RALD, while those who maintain their drinking status after leaving college remain stable and low on these two RALD factors (Figures 4c and 4d). Again, there are a number of potential explanations for these changes. With regard to Convictions RALD, it may be that transitioning to adult roles, such as marriage and parenting, is related to re-investment in “family” influenced convictions and possibly religious participation. It may also be due to changes in the acceptability of drinking among one’s friendship circles. Similarly with Loss of Control RALD, if drinking and especially heavy drinking is less acceptable and incompatible with current roles, concerns about getting into trouble, losing control, or being obnoxious may take on new meaning and thus be relevant once again. Overall, results from both of these transition analyses offer some evidence for the construct validity of the RALD factors in this study.

Mean-level and Moderating Effects of Sex and Family History on RALD and its Associations with Abstention

Family history positive participants reported stably higher importance of Loss of Control RALD over time and overall higher importance of Adverse Consequences RALD than did participants who reported no family history of alcoholism. One plausible explanation of this relation could be that participants with a family history of alcoholism are more aware of the possibility that alcohol may cause them to lose control or result in adverse consequences as they may have witnessed this phenomenon in the home and that reasons associated with loss of control are therefore more salient. It is also plausible that awareness of the genetic contribution to alcohol dependence would result in children of alcoholics reporting concerns about loss of control and adverse consequences even in the absence of personal experience. These results were consistent across alternative analytic approaches as well as findings from Chassin & Berrera (1993), that Self-control RALD are more strongly correlated with reduced alcohol use among children of alcoholics compared to controls. In the present study, participants with a family history of alcohol problems exhibited both increased rates of abstention (48–61% of abstainers across waves were family history positive) and greater levels of heavy drinking (range of M = 8.4 to 45.7 compared to family history negative range of M = 6.0 to 32.9 across study waves). These two findings may help explain the inconsistent cross-sectional relations between Loss of Control RALD and abstention status and drinking as presented in Table 2.

Relative to the moderating effects of family history of alcoholism, we found little mean-level or moderating effects of sex in our study, with the exception of differential change in Loss of Control RALD over time for males and females. Women begin college with relatively less experience with heavy drinking than their male counterparts (Sher & Rutledge, 2006), perhaps resulting in elevated concerns about loss of control early in the college years that diminish over time as experience accumulates and the ability to regulate drinking behavior increases.

In addition to supporting previous findings of differential cross-sectional relations, these results provide important and novel findings regarding the reciprocal influences of RALD and abstention. The most noteworthy findings suggest that only Convictions RALD are predictive of future abstention (only at year 16; see Figure 5). Conversely, abstention was predictive of later increases in Convictions RALD (at Years 4 and 7). These findings suggest that aspects of the social-normative environment, which are difficult to modify through primary prevention campaigns (e.g., religious affiliation or friend group), may be among the most influential RALD. While attempts to sensitize individuals to the negative consequences of their consumption, though potentially more feasible, might not alter drinking. Thus these findings suggest that Adverse Consequences and Loss of Control RALD may be more appropriately thought of as indicators of problem or dependent drinking than as RALD that impact future alcohol consumption. Future replication of these findings is needed before firm conclusions can be made about the potential for awareness of negative consequences to motivate decreases in alcohol consumption.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations that should be noted. First, and consistent with the larger literature on reasons for abstention, the measure used to assess RALD has not been shown to be comprehensive. There were only 10 items that were assessed at each wave of data collection and it is arguable that this is not a sufficient number of items to assess all possible content domain areas within RALD. Specifically, the results suggest that our measure may not have adequately sampled from the content domain associated with Convictions RALD as having only two items on a factor is not psychometrically ideal. Future research should consider additional items associated with the Upbringing/Conviction domain of RALD that might improve our existing measure. Second, the study sample contains a high-risk subsample of children of male alcoholics. Given that family history was associated with RALD, the generalizability of these findings to more representative samples cannot be assumed. Our sample was also relatively homogenous with regard to ethnicity, which also limits generalizability beyond predominantly Caucasian samples. In addition, the use of virtual abstention as an outcome variable may also limit generalizability to the phenomenon of strict abstention. However, the rates of strict abstention were too low in our sample to allow us to conduct the analyses on strict abstainers. There are a number of reasons why we might expect the rate of actual abstention to be low in this sample: large public university, active fraternity/sorority segment, Division I athletic programs, and oversampling for family history of alcohol problems. Third, although results from this study are largely consistent with existing literature, no study to date has looked at the reciprocal influences of RALD and abstention status and therefore these findings will need to be replicated in future work. Additional future research should examine other alcohol variables other than abstention status as well as additional predictors of RALD such as personality traits, alcohol expectancies, and reasons for drinking. Despite these limitations, our study has a number of strengths. We included both abstainers and drinkers, used prospective data spanning 17 years with excellent retention over time, were able to examine two important developmental transitions that occur in young adulthood, and included both sex and family history of alcohol problems as potential moderators.

Implications for Prevention and Intervention

Continued effort in the area of abstention motives will inform future policies regarding alcohol consumption prevention and intervention. There are at least two possible implications for RALD research in the area of alcohol prevention and intervention. First, much like positive alcohol expectancies have led to campus intervention programs across the nation designed to challenge these expectancies (Lau-Barraco & Dunn, 2008; Musher-Eizenman & Kulick, 2003; van de Luitgaarden, Wiers, Knibbe, & Candel, 2007; Wood, Capone, Laforge, Erickson, & Brand, 2007), it has been thought that once more was known about abstention motives, additional prevention and intervention programs would follow as alternatives to current programs or to enhance existing ones. Given the findings of this study, programs that might seek to increase (or create) specific abstention motives with the intention of decreasing alcohol consumption may not be feasible for two reasons. First, it would likely be difficult to increase Convictions RALD in young adulthood and beyond. Second, it appears that the more malleable RALD (such as Loss of Control and Negative Consequences) have very little, if any, influence on future drinking. A second possible implication is that RALD research might inform motivational enhancement interventions (such as Motivational Interviewing; Miller & Rollnick, 2002) by providing information about which motives are particularly influential in decreasing consumption. Thus increasing the focus on abstention motives related to convictions may be more productive than focusing on those related to consequences. However, before interventions can be designed or modified, additional research aimed at describing and understanding the relation between alcohol-related cognitions such as abstention motives and future drinking behaviors is needed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) R01AA016392, T32AA013526, K05AA017242, and P50AA011998 (PI: Kenneth J. Sher).

Appendix

INSTRUCTIONS

The following list includes some of the reasons others have given for why they do not drink or why they limit the amount they drink. We would like to know how much importance you attach to these concerns in limiting your own drinking. For each one, mark the answer that tells how important a concern is in limiting your own drinking.

RESPONSE OPTIONS

(0) strongly disagree; (1) slightly disagree; (2) slightly agree; (3) strongly agree

ITEMS

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because it’s against my religion to drink.

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because I sometimes become rude or obnoxious when I drink.

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because I’m afraid I might become an alcoholic if I drink too much.

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because the people I hang around with are against drinking.

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because it’s not healthy to drink too much.

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because I’m scared I’ll get into trouble.

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because I worry that I might not be able to control myself.

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because I feel physically ill after drinking.

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because it could interfere with my carrying out my responsibilities (like school work, my job).

I sometimes limit my drinking (or don’t drink at all) because it’s expensive.

Footnotes

Rates of past-12-month abstention in the National Epidemiological Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) were 26.37%, SE = 1.53 and 20.39%, SE = 0.74 among 18–22 year-olds and 23–34 year-olds, who attended at least some college, respectively (NESARC, 2001–2005).

These logically derived groups were compared to four similar classes that were empirically derived from a latent class growth analysis that allowed for missing data. The Kappa statistic (.80) suggested adequate reliability between the two techniques. For the sake of simplicity and ease of replicability, all further analyses involving these categories will use the logically derived groups.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/adb

References

- Adams SL, McNeil DW. Negative Alcohol Expectancies Reconsidered. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 1991;5:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Adams CE, Nagoshi CT. Changes over one semester in drinking game playing and alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Substance Abuse. 1999;20:97–106. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo M, Kurtz NR. Coping methods and reasons for not drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:1591–1610. doi: 10.3109/10826089809058946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo M, Kurtz N, Cutter HS. Abstinence, reasons for not drinking, and life satisfaction. International Journal of the Addictions. 1992;27(6):707–716. doi: 10.3109/10826089209068762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl Mar):40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM. Drinking among adolescents: A subcultural phenomenon or a model of adult behaviors. Adolescence. 1981;16:211–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Barrera M. Substance use escalation and substance use restraint among adolescent children of alcoholics. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1993;7:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cho SB, Wood PK, Heath AC. Decomposing group differences of latent means of ordered categorical variables within a genetic factor model. Behavior Genetics. 2009;39:101–122. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Koutsky JR, Izzo CV. Temptation, restriction, and the regulation of alcohol intake: Validity and utility of the Temptation and Restraint Inventory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:766–773. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Koutsky JR, Morsheimer ET, MacLean MG. Binge drinking among underage college students: A test of a restraint-based conceptualization of risk for alcohol abuse. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:333–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cotner CL. In their own words: College students who abstain from drinking. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; Blacksburg, VA: 2002. Unpublished Master of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman L, Harvey B, Holowaty P, Shortt L. Alcohol use beliefs and behaviors among high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:48–58. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Del Boca FK, Darkes J. Alcohol expenctancy theory: The application of cognitive neuroscience. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. New York: The Guildford Press; 1999. pp. 203–246. [Google Scholar]

- Gotham HJ, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Predicting stability and change in frequency of intoxication from the college years to beyond: Individual-difference and role transition variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:619–629. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K. Alcohol abstention among older adults: Reasons for abstaining and characteristics of abstainers. Addiction Research. 1998;6:473–487. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Guydish J, Temple MT. Reasons students give for limiting drinking: A factor analysis with implications for research and practice. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:108–115. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock VM, O’Brien J, Weinstein M, Carter-Menendez N. Reasons for drinking and alcohol use in young adults at high risk and at low risk for alcoholism. British Journal of Addiction. 1987;82:1335–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton ME. Abstention in the general population of the U.S.A. British Journal of Addiction. 1986;81:95–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TJ, Cohen EA. College students’ reasons for not drinking and not playing drinking games. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:1137–1160. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Schwitters SY, Wilson JR, Nagoshi CT, McClearn GE. A cross-ethnic comparison of reasons given for using alcohol, not using alcohol or ceasing to use alcohol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1985;46:283–288. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, Corbin W, Fromme K. A review of expectancy theory and alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2001;96:57–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H. The exceptions to the rule: Why nondrinking college students do not drink. College Student Journal. 1990;24:57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Knupfer G, Room R. Abstainers in a metropolitan community. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1970;31:108–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Barraco C, Dunn ME. Evaluation of a single-session expectancy challenge intervention to reduce alcohol use among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:168–175. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig AM. On and off the wagon: Reasons for drinking and abstaining by alcoholics. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1972;33:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg J. Reasons to drink and not to drink: Altering trajectories of drinking through an alcohol misuse prevention program. Applied Developmental Science. 1998;2:48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Millsap RE, Yun-Tein J. Assessing factorial invariance in ordered-categorical measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:479–515. [Google Scholar]

- Moore M, Weiss S. Reasons for non-drinking among Israeli adolescents of four religions. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 1995;38:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musher-Eizenman DR, Kulick AD. An alcohol expectancy-challenge prevention program for at risk college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:163–166. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Muthen LK. Mplus [Computer software] Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Muthen LK. The development of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a U. S. national sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:290–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus Users Guide. 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi CT, Nakata T, Sasano K, Wood MD. Alcohol norms, expectancies, and reasons for drinking and alcohol use in a U.S. versus a Japanese college sample. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 1994;18:671–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. 2001–2005 Database available online at http://www.nesarc.niaaa.nih.gov/

- Orford J. Excessive appetites: A psychological view of addictions. 2. New York: Wiley; 2001. p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves DW, Draper TW. Abstinence or decreasing consumption among adolescents: Importance of reasons. International Journal of the Addictions. 1984;19:819–825. doi: 10.3109/10826088409057225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. Chicago, IL, US: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK, Raskin G. Alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol use: a latent variable cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:561–574. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slicker EK. University students’ reasons for not drinking: Relationship to alcohol consumption level. Journal of Alcohol & Drug Education. 1997;42:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Goldman MS, Greenbaum PE, Christiansen BA. Expectancy for social facilitation from drinking: the divergent paths of high-expectancy and low-expectancy adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:32–40. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke WGK, Butt JCM. Motives for not drinking alcohol among Australian adolescents: Development and initial validation of a five-factor scale. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:633–649. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Luitgaarden J, Wiers RW, Knibbe RA, Candel MJJM. Single-session expectancy challenge with young heavy drinkers on holiday. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2865–2878. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Capone C, Laforge R, Erickson DJ, Brand NH. Brief motivational intervention and alcohol expectancy challenge with heavy drinking college students: A randomized factorial study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2509–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Nagoshi CT, Dennis DA. Alcohol norms and expectations as predictors of alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1992;18:461–476. doi: 10.3109/00952999209051042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]