Abstract

Purpose

To identify the disease-causing genes in families with autosomal recessive RP (ARRP).

Methods

Families were screened for homozygosity at candidate gene loci followed by screening of the selected gene for pathogenic mutations if homozygosity was present at a given locus. A total of 34 families were included, of which 24 were consanguineous. Twenty-three genes were selected for screening. The presence of homozygosity was assessed by genotyping flanking microsatellite markers at each locus in affected individuals. Mutations were detected by sequencing of coding regions of genes. Sequence changes were tested for presence in 100 or more unrelated normal control subjects and for cosegregation in family members.

Results

Homozygosity was detected at one or more loci in affected individuals of 10 of 34 families. Homozygous disease cosegregating sequence changes (two frame-shift, two missense, and one nonsense; four novel) were found in the TULP1, RLBP1, ABCA4, RPE65, and RP1 genes in 5 of 10 families. These changes were absent in 100 normal control subjects. In addition, several polymorphisms and novel variants were found. All the putative pathogenic changes were associated with severe forms of RP with onset in childhood. Associated macular degeneration was found in three families with mutations in TULP1, ABCA4, and RP1 genes.

Conclusions

Novel mutations were found in different ARRP genes. Mutations were detected in approximately 15% (5/34) of ARRP families tested, suggesting involvement of other genes in the remaining families.

Retinal dystrophies are a group of genetically and clinically heterogeneous disorders involving degeneration of the photoreceptors and resulting in partial or complete blindness. Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the most common clinical expression, but this condition represents a clinical manifestation of diverse genetic errors that are inherited as autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, digenic, or mitochondrial disorders. The manifestation and course of RP can show considerable variation between individuals, and onset of the disease can vary from childhood to adolescence or early adulthood. Initial symptoms include night blindness in the early stages coupled with decreased visual acuity and progressive loss of visual fields. Clinically, changes in the retina include pallor of the optic disc, attenuated vasculature, pigmentary deposits appearing as bony spicules, atrophy of retinal tissue and diminished electroretinographic responses. The prevalence of RP ranges from 1 in 5000 to 1 in 1000 in different parts of the world.1–3 ARRP appears to be relatively more common than dominant or X-inked forms in patient populations.4,5 Approximately 50 genes are known for RP (RetNet-http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet; provided in the public domain by the University of Texas Houston Health Science Center, Houston, TX). Mutations in known genes are detectable in only a subset of patients with RP, suggesting that more genes are yet to be identified.6 Functionally, RP genes are diverse, and encoded proteins are involved in a variety of cellular processes that are retina-specific as well as ubiquitous.

This study was designed to identify genes underlying ARRP in affected families. We screened 34 ARRP families for homozygosity at 23 loci for possible involvement in disease. The 23 loci belong to a subset of loci commonly involved in RP and related disorders or were candidates based on expression and function. Screening was done in two stages. First, we performed genotyping of microsatellite markers flanking each of the 23 genes to test for homozygosity at any of these loci among affected individuals. In the second stage, we sequenced coding regions of genes present at homozygous regions for pathogenic mutations.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Probands with a family history suggestive of recessive RP were included in the study and available family members were enrolled. All subjects, both affected and unaffected, were clinically evaluated and informed consent was obtained. A total of 34 families with 2 or more affected individuals were recruited; 24 families were consanguineous and 10 were non-consanguineous. Essential diagnostic criteria for inclusion included bilateral, diffuse, and widespread retinal pigment epithelial degeneration, arterial narrowing, commensurate visual field loss, and reduced amplitudes on electroretinogram (ERG) reduced to less than 25% of the maximum retinal response in normal individuals (normal amplitude of b-wave >350 μV and a-wave >110 μV) with evidence of rod and cone involvement. Other clinical signs that were supportive but not essential for diagnosis of RP included pigment migration including bone–corpuscular pigmentation, vitreous opacities and vitreous pigments, associated retinal pigment epithelium atrophic changes in the macular area, and diffuse disc pallor. Excluded were patients who had unilateral disease, nystagmus, and eye-poking behavior in childhood; exudative retinal detachment; retinal vasculitis; chorioretinitis; or any other secondary cause of pigmentary retinal changes. Clinical features of patients were reviewed and confirmed independently by two ophthalmologists.

Blood samples were collected from the affected and unaffected members of the families by venipuncture. The DNA was extracted from this blood by the phenol-chloroform method.

Twenty-three candidate genes were selected for screening, which included 14 known genes for ARRP: phosphodiesterase 6A (PDE6A), phosphodiesterase 6B (PDE6B), rhodopsin (RHO), cyclic nucleotide gated channel alpha 1 (CNGA1), cyclic nucleotide gated channel beta 1 (CNGB1), crumbs homolog 1 (CRB1), retinitis pigmentosa 1 (RP1), neural retina leucine zipper (NRL), ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 4 (ABCA4), cellular retinaldehyde binding protein 1(RLBP1), retinal pigment epithelium protein 65 kDa (RPE65), retinal G-protein coupled receptor (RGR), tubby-like protein 1 (TULP1), and prominin 1 (PROM1); 7 genes for related disorders such as Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), cone-rod dystrophy (CRD), and dominant/digenic RP: guanylate cyclase 2D, membrane (retina-specific) (GUCY2D), guanylate cyclase activator 1A (GUCA1A), rod outer segment membrane protein 1 (ROM1), retinal degeneration slow (RDS), cone-rod homeobox (CRX), aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein-like 1 (AIPL1), and RPGR interacting protein 1 (RPGRIP1); and 2 genes that are candidates for retinal dystrophy but have not yet been shown to have mutations in humans: phosphodiesterase 6G (PDE6G) and cellular retinol binding protein 1 (RBP1). Each locus was screened for homozygosity by genotyping 2 or more microsatellite markers (total of 57 markers). Microsatellite markers were selected based on reported high heterozygosity (0.7 or more) and were generally located within an interval of ~5 to 10 Mb of the candidate gene. Information on the primers for amplification of microsatellite markers, marker heterozygosity, and location was obtained from the UniSTS (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=unists) Human Genome Database and NCBI Mapview, (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/) databases (both provided in the public domain by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD). The detection of homozygosity at a given locus shared only by affected members but not by unaffected family members was investigated further by typing additional markers at the locus for confirming homozygosity and subsequent screening of the relevant gene for mutations. Uninformative loci in which affected as well as one or more unaffected members were homozygous, were genotyped with additional markers. Genotyping was performed for 76 affected and 88 unaffected individuals from 34 families. Genotyping was performed in multiplex PCR reactions followed by electrophoresis (model 310 genetic analyzer; ABI). Alleles were determined by using genotyping software (GeneScan; Applied Biosystems Inc, Foster City, CA). Screening of coding regions of genes was performed by PCR amplification of exons and adjacent intronic regions, followed by direct automated sequencing. The sequence changes observed were checked for cosegregation in the family and for presence or absence in at least 100 healthy control individuals by RFLP or direct sequencing. For RFLP, restriction enzyme-digested products were resolved on 8% or 10% acrylamide gels and visualized after ethidium bromide staining.

Multiple sequence alignment of protein sequences was performed using ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html; European Bioinformatics Institute, Cambridge, UK). Sorting intolerant from tolerant (SIFT) analysis (http://blocks.fhcrc.org/sift/ provided in the public domain by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) was used to predict the potential impact of a missense substitution on protein function. A SIFT score below the cutoff of 0.05 for a given substitution is classified as not tolerated while those with scores higher than this value are considered tolerated.

Results

Based on genotypes obtained at markers flanking the 23-gene loci, homozygosity specific for affected members was detected at 12 loci in 10 of 34 families (details in Table 1). Screening of the relevant candidate genes in these cases showed putative pathogenic changes in five genes (listed in Table 2). Several polymorphisms and other variants of uncertain significance were also detected, of which the novel polymorphisms are listed in Table 3. A summary of findings in families with mutations is given in the following sections.

Table 1.

Details of Families with ARRP and Loci Showing Homozygosity

| Chromosomal Location | Gene | Family | Informative Markers | Distance of the Farthest Marker from the Gene (Mb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p31 | RPE65 | RP205 | D1S2829, D1S1162 | 0.6 |

| 1q31-q32.1 | CRB1 | RP126, RP160 | D1S1726, D1S373, D1S1181, D1S2853, D1S2622 | 2.8 |

| 1p22.1-p21 | ABCA4 | RP213 | D1S236, D1S1170, D1S188 | 1.9 |

| 4p16.3 | PDE6B | RP119 | D4S3038, D4S412, D4S432, D4S2936, D4S3023, D4S2285 | 4.5 |

| 4p12-cen | CNCG1 | RP200 | D4S405, D4S174, D4S2996, D4S2971 | 7.5 |

| 6p21.3 | TULP1 | RP126 | D6S1568, D6S1629, D6S1583, D6S273 | 3.7 |

| 8q11-q13 | RP1 | RP170 | D8S285, D8S1718, D8S1696 | 8.3 |

| 10q23 | RGR | RP160, RP184 | D10S1753, D10S1744, D10S1755, D10S1765 | 6.3 |

| 14q11.1-q11.2 | NRL | RP153 | D14S1042, D14S990 | 4.7 |

| 15q26 | RLBP1 | RP169 | D15S972, D15S1046, D15S111, D15S963, D15S202 | 3.8 |

Families and the gene loci are shown with corresponding markers at which homozygosity was identified, with the distance of the marker farthest from the gene.

Table 2.

Putative Pathogenic Changes Found in ARRP

| Family | Gene | Location | Mutation cDNA,Protein | Consequence | Reported/Novel | Restriction Site Change, if Any |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP205 | RPE65 | Exon 10 | c.1060delA, p.Asn356fs | Frame shift | Reported7 | None |

| RP170 | RP1 | Exon 4 | c.2847delT, p.Asn949fs | Frame shift | Novel | None |

| RP126 | TULP1 | Exon 12 | c.1199G>A, p.Arg400Gln | Missense | Novel | Eco57I+ |

| RP169 | RLBP1 | Exon 6 | c.451C>T, p.Arg151Trp | Missense | Novel | Hpy188III− |

| RP213 | ABCA4 | Exon 14 | c.1995C>A, p.T665X | Nonsense | Novel | None |

Pathogenic sequence changes identified.+, denotes gain of restriction site; −, denotes loss of restriction site. Numbering is with respect to first base of ATG. Sequences referred to above have the following Ensembl Transcript Ids: RPE65, ENST00000262340; RP1, ENST00000220676; TULP1, ENST00000229771; RLBP1, ENST00000268125; and ABCA4, ENST00000370225.

Table 3.

Novel Changes of Unknown Significance Identified in Families with ARRP

| Family | Gene | Location | Change in cDNA, Protein |

|---|---|---|---|

| RP126 | CRB1 | Exon 8 | c.2715G>A, p.Arg905Arg |

| RP213 | ABCA4 | Exon 29 | c.4256T>C, p.Met1419Thr |

| RP119 | PDE6B | Intron 10 | c.1401+31C>A |

| RP119 | PDE6B | Intron 17 | c.2130−15G>A |

| RP160 | RGR | Exon 2 | c.123C>T, p.Phe41Phe |

| RP184 | RGR | Intron 6 | c.760-38C>T |

RPE65

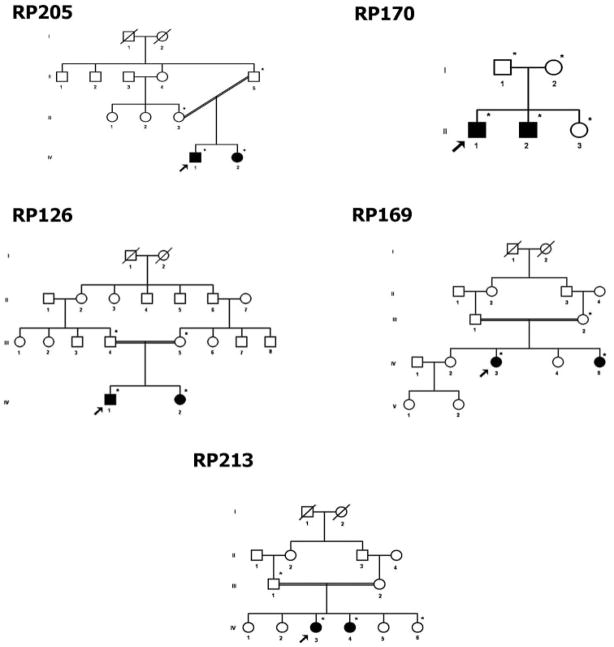

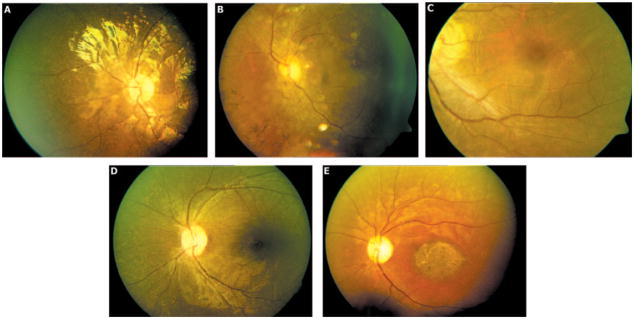

In family RP205 (pedigree shown in Fig. 1), homozygosity was detected at the RPE65 gene locus. Screening of the RPE65 gene showed a homozygous single-base deletion in exon 10 of RPE65 (cDNA change c.1060delA). This change cosegregated with the disease in the family. None of 103 control individuals tested by direct sequencing of PCR products of exon 10 showed this change. Both affected individuals had the initial symptom of night blindness reportedly by 1 year of age (Fig. 2A). The fundus showed arterial narrowing and white dots in the periphery caused by RPE atrophy. A diagnosis of early-onset RP was made in both patients in this family. Clinical features of the patients are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of families with ARRP in which pathogenic changes were identified.

Figure 2.

Representative fundus photographs of affected individuals of the following families with ARRP: (A) RP205, (B) RP170, (C) RP126, (D) RP169, (E) RP213.

Table 4.

Clinical Features of Affected Individuals from Families with ARRP

| Family/Gene Mutation | Patient* | Age at Presentation (y) | Age at Onset (y) | Initial Symptoms | Fundus Appearance | Visual Acuity | ERG | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP205/RPE65 | IV:1 | 7 | 1 | Night blindness | Arterial narrowing; widespread white dots in the periphery, due to RPE atrophy | 20/60 OD; 20/50 OS | Extinguished | Early-onset RP |

| IV:2 | 5 | 1 | Teller Acuity: 20/63 OU | ND | ||||

| RP170/RP1 | II:1 | 19 | NA, childhood | Night blindness, reduced vision | Equatorial and macular RPE degeneration, pale disc, arterial narrowing, vitreous opacities | OD 20/60; OS- counting fingers at 1 meter | ND | RP with macular degeneration |

| II:2 | 17 | 5 | 20/50 OU | ND | ||||

| RP126/TULP1 | IV:1 | 22 | NA, childhood | Night blindness, reduced vision | RPE degeneration, pigment migration, arterial narrowing with prominent macular degeneration, optic disc pallor | 20/200 OD; 20/200 OS | Extinguished | Advanced RP |

| IV:2 | 19 | NA, childhood | Night blindness, reduced vision; nystagmus | 20/400 OD; 20/600 OS | Extinguished | |||

| RP169/RLBP1 | IV:3 | 16 | NA, childhood | Night blindness, progressive loss of vision | RPE degeneration, pigment migration, arterial narrowing with macular sparing, discs normal, peripheral visual field constriction | 20/50 OU | ND | Typical RP |

| IV:5 | 12 | NA, childhood | 20/50 OU | ND | ||||

| P213/ABCA4 | IV:4 | 19 | 11 | Progressive visual loss | Equatorial RPE degeneration, pale disc, arterial narrowing, vitreous opacities, and a large patch of macular atrophy | 20/200 OU | Rod-cone pattern | RP with atrophic maculopathy |

| IV:3 | 21 | 13 | 20/200 OU | Rod-cone pattern |

NA, not available; ND, not done.

Individual ID corresponds to the ID in the pedigree.

RP1

Homozygosity was detected in two affected members of family RP170 (Fig. 1) at the RP1 gene locus. Screening of the RP1 gene showed four sequence changes: one novel single-base deletion (Table 2) and three reported SNPs. The single-base deletion c.2847delT cosegregated with the disease phenotype in the family and is predicted to result in a frame shift at codon 949, leading to a premature termination after 32 amino acid residues (p.Asn949LysfsX32). This change was not observed in any of the 202 control chromosomes screened for this deletion by direct sequencing. In the proband, three reported SNPs were identified in homozygous form (rs444772, rs414352, and rs441800 [c.5175A>G]; not shown). Affected individuals of this family had symptoms of night blindness beginning in childhood and progressively reduced visual acuity. The fundus showed equatorial RPE degeneration, pale disc, arterial narrowing, vitreous opacities, and macular RPE degeneration (Fig. 2B). Visual fields showed a central island of vision. This family had a diagnosis of RP with macular degeneration (Table 4).

TULP1

In family RP126 (Fig. 1) homozygosity among affected members was detected at two gene loci, TULP1 and CRB1, and hence both the genes were selected for mutation screening.

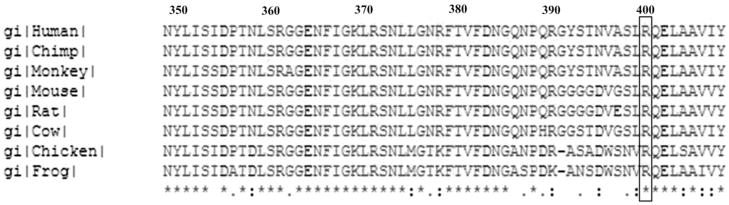

Five homozygous sequence changes were found in the TULP1 gene in the proband RP126/1, including one novel missense change and four reported SNPs. A single-base substitution of c.1199G>A was found in exon 12 of the gene, corresponding to a missense change Arg400Gln (Table 2). This change cosegregated with the disease phenotype and was absent in 109 normal control individuals screened by using restriction enzyme Eco57I. As shown in Figure 3, Arg400 is highly evolutionarily conserved, suggesting that the alteration in this residue would be pathogenic. SIFT analysis of this substitution predicts that this change may be damaging to the protein (SIFT score, 0.00). Four reported SNPs (rs7764472, rs58984224, rs2064317, and rs2064318; data not shown) identified in this gene, were also homozygous in the proband.

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of TULP1 proteins from different species. Box: arginine residue at position 400, the site of the mutation.

Two affected individuals in this family showed initial symptoms of night blindness in childhood, followed by progressively reduced vision. The fundus showed diffuse RPE degeneration, pigment migration, arterial narrowing with prominent macular degeneration, and optic disc pallor (Fig. 2C, Table 4). The affected individuals had a diagnosis of advanced RP.

RLBP1

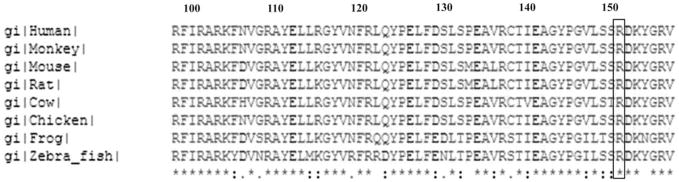

In family RP169 (Fig. 1), homozygosity was detected at the RLBP1 gene locus. Screening of the proband RP169/3 for mutations in the RLBP1 gene showed a novel homozygous substitution in exon 6 (c.451C>T; Table 2), which predicts a missense change Arg151Trp. This change cosegregated with the disease phenotype in RP169. One hundred eight control individuals were tested for the presence of this change by restriction digestion of the PCR-amplified product of exon 6 with restriction enzyme Hpy188III. None of the control chromosomes was positive for the change. The Arg151 residue is conserved among different species (Fig. 4), suggesting that it is essential for protein function. The SIFT score for this change was 0.00, predicting that it is deleterious to the protein.

Figure 4.

Multiple sequence alignment of the RLBP1 protein sequence in different species. Box: arginine residue at position 151, the site of the mutation.

The affected individuals of this family presented to us at 16 and 12 years of age (Table 4). In both individuals, night blindness began in childhood. The fundus showed diffuse RPE degeneration, pigment migration, and arterial narrowing with macular sparing (Fig. 2D). They had a visual acuity of 20/50 in both eyes. A diagnosis of RP was made in both.

ABCA4

Genotyping of the 23 candidate gene loci in family RP213 (Fig. 1) indicated homozygosity at the ABCA4 gene locus. Screening of the ABCA4 gene revealed seven homozygous sequence changes in the proband. One novel nonsense mutation Tyr665X (c.1995C>A; Table 2) cosegregated with the disease phenotype in family RP213. The Tyr665X change was absent in 101 control individuals (202 chromosomes). This change leads to premature truncation of the ABCA4 protein and is predicted to result in complete loss of two ATP binding domains: partial loss of the first and second transmembrane domains.8 Among the other variants found in ABCA4, one novel missense change Met1419Thr (c.4256T>C) was found (Table 3) that leads to abolition of one of the restriction sites for NlaIII in the 229-bp PCR product of exon 29 of ABCA4. One hundred five normal control subjects were screened for this change by digestion with NlaIII. Five (4.8%) of 105 control individuals were heterozygous for Met1419Thr, suggesting that it is a polymorphic variant. Multiple sequence alignment of the ABCA4 proteins showed that this residue is not conserved among different species (not shown). SIFT analysis yielded a score of 0.16 for this substitution, interpreting it to be tolerated. Other homozygous sequence changes identified were reported SNPs (rs4847281, rs547806, rs55860151, rs1801359, and rs17110761; data not shown).

Affected individuals in family RP213 showed onset of visual loss at 9 and 11 years of age. The fundus showed equatorial RPE degeneration, a pale disc, arterial narrowing, and a large patch of macular atrophy (Fig. 2E). The ERG was extinguished for rods and severely reduced for cones. These patients had a diagnosis of RP with atrophic maculopathy (Table 4).

Changes Identified at the Remaining Loci Selected for Homozygosity

Five additional loci listed in Table 1 at which homozygosity was found (PDE6B, CRB1, CNCG1, RGR, and NRL) showed no pathogenic changes on sequencing. Nonpathogenic variants or changes of unknown significance found in these five genes are discussed in the following sections.

Affected members of RP126 also showed homozygosity at the CRB1 locus (Table 1). Screening of the CRB1 gene in the proband RP126/1 (Fig. 1) showed three homozygous sequence changes: one novel synonymous change (Arg905Arg; c.2715G>A; Table 3), and two reported SNPs (rs58879207 and rs3902057; data not shown).

The PDE6B gene locus showed homozygosity in family RP119 (Table 1). Screening of the PDE6B gene in the proband showed three homozygous sequence changes and one heterozygous change. A novel homozygous sequence change in intron 17, c.2130-15G>A, cosegregated with the disease phenotype and was absent in 108 normal control subjects. However, the splice site prediction program (www.fruitfly.org/seq-tools/splice.html; provided in the public domain by the Drosophila Genome Center, Department of Molecular and Cell Biology and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Berkeley, CA) suggests that the change is likely to be nonpathogenic, as the introduction of the sequence variant changes the accepter site prediction score from 0.90 to 0.89. In addition, no splice site was predicted to be created as a result of the mutation by the splice site prediction tools. Other changes in PDE6B were found in the proband including two reported SNPs (rs10902758 and rs28675771; not shown), both homozygous and a novel heterozygous intronic change, c.1401+31C>A (Table 3).

Screening of the CNCG1 gene in family RP200 (Table 1) revealed three reported SNPs (rs1972883 (homozygous), rs6819506 (homozygous), rs59800634 (heterozygous). The CRB1 locus was homozygous in family RP160. Two known SNPs (rs12042179 and rs3902057) were found in homozygous form in the proband. Screening of the RGR gene was performed in two families: RP160, and RP184 (Table 1). Changes detected in the proband from RP160 included the reported SNPs (rs2279227, rs1042454, rs61730895, and rs3526) in homozygous form and 1 novel heterozygous synonymous change (c.123C>T, p.Phe41Phe; Table 3). In family RP184, a novel homozygous intronic change (c.760-38C>T, Table 3) was observed in the RGR gene, which did not cosegregate with disease in the family. In family RP153, screening of the NRL gene showed no detectable sequence changes.

Discussion

The high degree of genetic heterogeneity in ARRP makes genetic screening and gene identification rather expensive and time consuming. The use of homozygosity to detect disease gene loci for ARRP enables a relatively rapid screening of a large number of loci and is particularly useful in analysis of consanguineous families in which regions of several centimorgans adjacent to the disease gene are expected to be homozygous by descent.9 This approach is well suited to screening consanguineous ARRP families, as in this study. Gene identification in families with ARRP has been performed by homozygosity screening both in screenings of preexisting/candidate gene loci10,11 and genome-wide screening.12 Screening of 23 loci in the present study identified putative pathogenic alterations in five different genes in 5 (~15%) of 34 families. Two frame-shift, two missense, and one nonsense sequence changes were detected, of which four had not been reported.

Three of the mutations are of probable severe consequence, since they encode prematurely truncated proteins. Two are single-base deletions: c.1060delA in the RPE65 gene, expected to result in a frame shift at codon 356 with premature truncation at codon 371 (p.Asn356MetfsX16), and c.2847delT in the RP1 gene, predicting a frame shift at codon 949 and premature termination after 32 amino acids (p.Asn949LysfsX32). Mutations in RP1 known so far to cause ARRP are one missense, two insertions, and two deletions reported in two studies involving families of Pakistani origin.13, 14 The phenotype of patients in the present study is comparable with those reported in the Pakistani families, with typical fundus changes including disc pallor and vascular attenuation and an onset of disease in childhood. We also noted the presence of macular degeneration in family RP170, whereas Khaliq et al.13 described macular stippling. A third mutation encoding premature termination is a novel nonsense mutation Tyr665X in the ABCA4 gene in family RP213, which is likely to be functionally null or lead to instability of the mRNA or protein due to a premature nonsense codon. The associated phenotype of severe, early-onset disease with early signs of maculopathy is part of the spectrum of phenotypes resulting from severe mutations in ABCA4.15,16

Two missense changes that we identified in two families were Arg400Gln (c.1199G>A) in the TULP1 gene and Arg151Trp (c.451C>T) in the RLBP1 gene. The high degree of conservation of residues involved in the two cases (Figs. 3, 4), the predicted SIFT scores of 0.00, and the nature of the substitutions both of which replace a charged amino acid with a neutral one, argue in favor of their pathogenicity. Codon Arg400 is located in the highly conserved C-terminal tubby domain of the TULP1 protein17 in which mutations reported so far in TULP1 are also located. The Arg400 residue is conserved among TUB, TULP1, TULP3, Drosophila king tubby, and Caenorhabditis elegans tub-1.18 The same residue has been described to have the mutation R400W.19 The phenotype observed in this family (Table 3; Fig. 2) is one of severe, early-onset RP, with one of the affected siblings having nystagmus. These features are similar to those described earlier in patients with TULP1 mutations.20,21 A notable feature is the presence of maculopathy in the patients in our study as well as those described by Lewis et al.20 The Arg151Trp mutation in RLBP1 in our study involves the same residue as the previously reported mutation Arg151Gln,22 shown to have decreased ability to bind 11-cis retinal.

The novel intronic change in the PDE6B (c.2130-15G>A) gene in family RP119 was absent in at least 100 normal control subjects and cosegregated with disease in family RP119. Analysis of this sequence change by means of splice site prediction software did not predict any adverse effect of the change. One possibility that could still be considered is that the G>A change at this site is unfavorable due to creation of the AG dinucleotide in the vicinity of the authentic splice acceptor. It has been suggested that AG dinucleotides are not found to occur within 15 bp upstream of position −4 of the intron,23 possibly to ensure specificity of the splice site selection. Hence, further investigations are needed to confirm the pathogenic/benign nature of this change. Although the PDE6B gene locus was selected for further analysis based on homozygosity among affected members of family RP119, the presence of a heterozygous sequence change (c.1401+31C>A) suggests that this locus is unlikely to be homozygous by descent. It is also possible that the heterozygous c.1401+31C>A change arose as a more recent mutation of one of the ancestral alleles.

RP is a major cause of blindness in Southern India, with a prevalence of 1 in 1000 in the state of Andhra Pradesh.24 Few studies on the genetics of RP have been reported in this region.25–27 Investigation into the genes underlying RP is potentially useful in designing genetic testing and counseling for patients. Our study revealed novel causes of disease in Indian families with ARRP, detecting mutations in RPE65, RP1, TULP1, RLBP1, and ABCA4 genes, revealing mutations in approximately 15% (5/34) of families with ARRP in the loci tested. Furthermore, this study paves the way for the screening of larger cohorts of patients with RP or families by using the same methods in combination with genome-wide screening and/or mapping to identify disease genes in all families.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and family members who participated, the staff of the clinical laboratory service of L. V. Prasad Eye Institute for technical assistance, and Robert J. Biggar, MD, for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Supported by Grant R01 TW06231 from the Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, under the Global Health Research Initiative Program (CK); the Department of Biotechnology, New Delhi, India; and the Champalimaud Foundation, Portugal. HPS was supported by a senior research fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), India.

Footnotes

Disclosure: H.P. Singh, None; S. Jalali, None; R. Narayanan, None; C. Kannabiran, None

References

- 1.Bundey S, Crews SJ. A study of retinitis pigmentosa in the City of Birmingham. I Prevalence. J Med Genet. 1984;21(6):417–420. doi: 10.1136/jmg.21.6.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunker CH, Berson EL, Bromley WC, Hayes RP, Roderick TH. Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in Maine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97(3):357–365. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu L, Hu L, Ma K, Li J, Jonas JB. Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in urban and rural adult Chinese: The Beijing Eye Study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16(6):865–866. doi: 10.1177/112067210601600614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayakawa M, Matsumura M, Ohba N, et al. A multicenter study of typical retinitis pigmentosa in Japan. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1993;37(2):156–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haim M. Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa and allied disorders in Denmark. III. Hereditary pattern. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1992;70(5):615–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1992.tb02142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannabiran C. Retinitis pigmentosa: overview of genetics and gene-based approaches to therapy. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2008;3(4):417–429. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marlhens F, Bareil C, Griffoin JM, et al. Mutations in RPE65 cause Leber’s congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 1997;17(2):139–141. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bungert S, Molday LL, Molday RS. Membrane topology of the ATP binding cassette transporter ABCR and its relationship to ABC1 and related ABCA transporters: identification of N-linked glycosylation sites. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(26):23539–23546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lander ES, Botstein D. Homozygosity mapping: a way to map human recessive traits with the DNA of inbred children. Science. 1987;236(4808):1567–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.2884728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lalitha K, Jalali S, Kadakia T, Kannabiran C. Screening for homozygosity by descent in families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. J Genet. 2002;81(2):59–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02715901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo H, Qin M, Mizota A, et al. A homozygosity-based search for mutations in patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa, using microsatellite markers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(12):4433–4439. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.den Hollander AI, Lopez I, Yzer S, et al. Identification of novel mutations in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis and juvenile RP by genome-wide homozygosity mapping with SNP microarrays. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(12):5690–5698. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khaliq S, Abid A, Ismail M, et al. Novel association of RP1 gene mutations with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. J Med Genet. 2005;42(5):436–438. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riazuddin SA, Zulfiqar F, Zhang Q, et al. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa is associated with mutations in RP1 in three consanguineous Pakistani families. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(7):2264–2270. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukui T, Yamamoto S, Nakano K, et al. ABCA4 gene mutations in Japanese patients with Stargardt disease and retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(9):2819–2824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh HP, Jalali S, Hejtmancik JF, Kannabiran C. Homozygous null mutations in the ABCA4 gene in two families with autosomal recessive retinal dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(5):906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boggon TJ, Shan WS, Santagata S, Myers SC, Shapiro L. Implication of tubby proteins as transcription factors by structure-based functional analysis. Science. 1999;286(5447):2119–2125. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.den Hollander AI, van Lith-Verhoeven JJ, Arends ML, Strom TM, Cremers FP, Hoyng CB. Novel compound heterozygous TULP1 mutations in a family with severe early-onset retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(7):932–935. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.7.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanein S, Perrault I, Gerber S, et al. Leber congenital amaurosis: comprehensive survey of the genetic heterogeneity, refinement of the clinical definition, and genotype-phenotype correlations as a strategy for molecular diagnosis. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(4):306–317. doi: 10.1002/humu.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis CA, Batlle IR, Batlle KG, et al. Tubby-like protein 1 homozygous splice-site mutation causes early-onset severe retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(9):2106–2114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paloma E, Hjelmqvist L, Bayes M, et al. Novel mutations in the TULP1 gene causing autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(3):656–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maw MA, Kennedy B, Knight A, et al. Mutation of the gene encoding cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 1997;17(2):198–200. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mount SM. A catalogue of splice junction sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;22 10(2):459–472. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dandona L, Dandona R, Srinivas M, et al. Blindness in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(5):908–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumaramanickavel G, Maw M, Denton MJ, et al. Missense rhodopsin mutation in a family with recessive RP. Nat Genet. 1994;8(1):10–11. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Shetty J, Kumar B, Blanton SH. Confirmation of linkage and refinement of the RP28 locus for autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa on chromosome 2p14–p15 in an Indian family. Mol Vis. 2004;10:399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gandra M, Anandula V, Authiappan V, et al. Retinitis pigmentosa: mutation analysis of RHO, PRPF31, RP1, and IMPDH1 genes in patients from India. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1105–1113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]