Abstract

In this article we review the chemistry and nanoemulsion formulation of perfluorocarbons used for in vivo 19F MRI cell tracking. In this application, cells of interest are labeled in culture using a perfluorocarbon nanoemulsion. Labeled cells are introduced into a subject and tracked using 19F MRI or NMR spectroscopy. In the same imaging session, a high-resolution, conventional (1H) image can be used to place the 19F-labeled cells into anatomical context. Perfluorocarbon-based 19F cell tracking is a useful technology because of the high specificity for labeled cells, ability to quantify cell accumulations, and biocompatibility. This technology can be widely applied to studies of inflammation, cellular regenerative medicine, and immunotherapy.

IN VIVO CELL TRACKING USING MRI

Clinical Need

The persistence of complex, medical conditions, such as autoimmune diseases, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases, has prompted the development of cellular therapies. Cellular therapy is the treatment of disease using therapeutic cells that have been derived from the patient, a matched donor, other organisms, or immortalized cell lines. Often these cells are sorted, multiplied, pharmacologically treated and/or genetically transformed in culture prior to infusion or transplantation into a patient. Therapeutic cells have the potential to accomplish complex tasks such as the regeneration of tissues, for example replacing cartilage1,2 or brain cells,3 or to re-program a patient’s immune system, for example, to elicit an anti-tumor response.4,5 A common need for emerging cellular therapies is a non-invasive way to image the behavior and movement of cells following injection or transplantation into the subject. The ability to non-invasively monitor movement and accumulation of therapeutic cells would enable clinicians to determine whether cell delivery has occurred in the appropriate location, and whether—and to what degree—transplanted cells have reached their therapeutic location for each patient. In vivo cell tracking is potentially a powerful tool, providing critical feedback regarding the optimal routes of delivery and therapeutic doses for individuals. This feedback may come in the form of observed cell trafficking patterns and may also provide improved management of serious cell transplant side-effects, such as graft-versus- host disease.

Cell Tracking by MRI

MRI is a widely used clinical diagnostic tool because it is non-invasive, has no tissue depth penetration limitations, and provides contrast among soft tissues at reasonably high spatial resolution. Many laboratories have investigated the feasibility of using conventional 1H MRI to visualize immune cells, stem cells, and other cell types. In certain studies, cultured cells are rendered magnetically distinct ex vivo via the internalization of paramagnetic contrast agents, for example, using nanometer- or micron-sized superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) particles.6–11 There are also numerous studies where iron oxide particles have been used to label macrophages in vivo (i.e., in situ) upon direct injection (e.g., see reviews12–16). On a more limited basis, perfluorocarbon (PFC) nanoemulsion formulations have also been used for 19F MRI cell tracking17–20 as an alternative to SPIO agents. PFC nanoemulsions have been shown to label monocytes and macrophages in situ when injected intravenously and provide positive signals at sites of inflammation in animal models.20,21

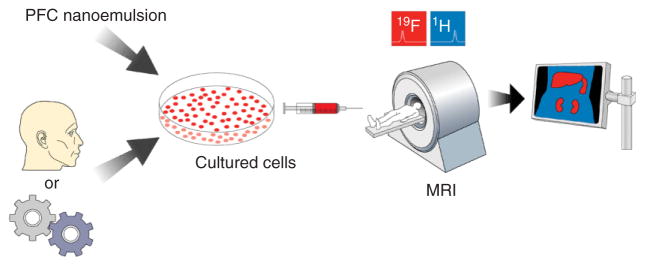

Recently, 19F cell tracking methodologies have been developed that rely on ex vivo cell labeling with PFC. In this approach, cells of interest are labeled with a PFC nanoemulsion, injected or transplanted into a subject and the cell migration is monitored in vivo using spin-density weighted 19F MRI. Figure 1 shows the overall scheme of this methodology. The key advantage of this platform is that the 19F images are extremely selective for the labeled cells i.e., there is negligible background signal from the host’s tissues.19 Furthermore, ex vivo labeling allows for tracking of phenotypically-defined cell types of interest.

FIGURE 1.

Cellular MRI using PFC nanoemulsion technology. PFC nanoemulsion is added to cultured cells that have been harvested from a subject or an engineered line. The labeled cells are transplanted into the subject and imaged using 19F and 1H MRI in the same imaging session. The registered images are overlaid, yielding an image of the labeled cells in their anatomical context.

The detection of PFC labeled cells using 19F MRI (or MRS) is fundamentally different from prior methods for labeling cells with paramagnetic agents. In the case of the latter, one detects the presence of the paramagnetic agent indirectly via its effect on T1, T2, and/or T2* of surrounding protons in mobile water. In contrast, the PFC reagent acts like a ‘tracer’, and 19F magnetic resonance directly detects the density of 19F spins contained in the PFC droplets inside the cells.

The first proof-of-principle demonstration of in vivo 19F cell tracking using ex vivo cell labeling was published in 2005;19 in these studies PFC labeled mouse dendritic cells (DCs) were imaged. In follow-up studies, our laboratory has focused on labeling and tracking T cells in the context of following early inflammatory events in the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse model.22 Other laboratories have also used 19F MRI methodologies to visualize ex vivo labeled stem/progenitor cells in vivo.17 These examples demonstrate the breadth of possible applications of 19F MRI cell tracking.

In this article we describe the challenges and solutions for the design and synthesis of effective 19F MRI reagents for ex vivo cell labeling using PFC. We will also briefly discuss recent examples where these 19F cell tracking methodologies have been applied to animal models.

PERFLUOROCARBONS IN 19F MRI

Physicochemical Properties

PFCs have been studied for more than 40 years and are among the most chemically and biologically inert organic synthetic molecules ever produced.23 The exceptionally strong carbon–fluorine covalent bond and the strong electron withdrawing effects of fluorine are responsible for the unusual physicochemical properties of PFCs. These molecules are highly hydrophobic, and in most cases significantly lipophobic. Due to the low polarizability of the fluorine atom, PFCs exhibit very low Van der Waals forces resulting in very low intermolecular cohesion, low surface tension, and high vapor pressure. These unusual physicochemical properties explain the ability of PFCs to dissolve oxygen, carbon-dioxide and nitrogen. Sharts and Reese24 have shown that in emulsified linear perfluorocarbons, the number of fluorines directly correlates to its ability to solubilize oxygen. The first biological applications of PFCs exploited the high oxygen solubility. In 1966, Clark and co-workers demonstrated that mice could survive for 24 h while submersed in fluorocarbon liquid saturated with oxygen.25 High hydrophobicity and substantial lipophobicity of PFCs, and the consequent high tendency to segregate from the surrounding environment, are partially responsible for PFCs being biological inert and the absence of toxicity in vivo even at very high doses.

Perfluorocarbons as 19F MRI Tracers

PFCs are a class of molecules that are potentially highly useful for intracellular MRI tracer applications. Fluorine has very low background biological abundance and is a sensitive atom for nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy or imaging. Compared to 1H, the gyromagnetic ratio of 19F differs by only about 6% and the relative sensitivity is 0.83. PFCs have a highly stable carbon–fluorine bond. There are no known enzymes that metabolize fluorocarbons in vivo,26 and they do not degrade at typical lysosomal pH values.27,28 The 19F NMR line shape and chemical shift of PFC is not altered within cells.19 PFCs are both lipophobic and hydrophobic and do not incorporate into cell membranes.27,28 Clearance of PFC agents from the body occurs via the reticuloendothelial system and exhalation through the lungs.29

The utility of PFCs as MRI reagents is highly dependent on the chemical structure. Overall, optimal reagents for 19F MRI applications should satisfy several design criteria, including: (i) chemical stability, (ii) a simple 19F NMR spectrum, ideally having a single, narrow resonance to maximize sensitivity and prevent chemical shift imaging artifacts, (iii) a short 19F T1 and long T2 to minimize data acquisition time.

A structural survey of PFCs used for MRI is shown in Figure 2. These structures can be classified into five groups: (a) aromatic and unsaturated PFCs (hexafluorobenzene, trans-1,2-bis(perfluorbutyl)-ethylene), (b) saturated linear PFCs (PFOB, PFOA, perfluorononane), (c) saturated ring system PFCs (perfluorodecalin, perfluoroperhydrophenanthrene), (d) perfluoroamines (FC-43) and (e) perfluoroethers and polyethers [PTBD, perfluoro-15-crown-5 ether (PCE), PFPE, FBPA]. From the structures shown in Fig. 2, only a few PFCs have been used for MRI cell tracking (PFPE, PCE, perfluorodecalin, PFOB), and of these, two have a large number of NMR-equivalent fluorine atoms (PCE and PFPE). Specific PFC examples and their properties as MRI tracers are discussed in detail bellow.

FIGURE 2.

Perfluorooctyl bromide [(PFOB) perfluorobron, Figure 2(b)], a linear PFC, was one of the earliest applied as a 19F MRI tracer.35 It has been used for oxygen sensing,36,37 imaging tumors,38 atherosclerotic plaques,39 and cell tracking.17 PFOB is hydrophobic and, unlike most PFCs, shows a small but finite lipophilicity due to the covalently-bound bromine. The limited membrane solubility localizes PFOB to the center of lipid bilayers.40 The PFOB 19F NMR spectrum consists of eight peaks, one for each CFn moiety; its use for cell tracking is non-ideal in terms of sensitivity and requires the use of a frequency selective MRI pulse sequence to limit chemical shift artifacts, for example, by incorporating presaturation RF pulses on undesired resonance peaks prior to imaging.

Perfluorotributylamine [(FC-43), Figure 2(d)], has been used for in vivo oxygen sensing in porcine models.41 FC-43 also shows multiple 19F peaks, and thus its use for imaging is as challenging as in the case of PFOB. Perfluorinated ether PTBD (Figure 2(e)) was introduced as an improvement for oxygen sensing by 19F MRI. It has a 19F spectrum less complex than PFOB or perfluorotributylamine, with 12 equivalent fluorines from the CF3 groups. PTBD can be imaged without the use of MRI pulse sequences that suppress chemical shift artifacts. Overall, PTBD shows an increase in sensitivity of 17% over PFOB at the same molar concentration.42

Further improvement in MRI sensitivity is possible with perfluorinated ether PCE (Figure 2(e)), a chemically and biologically inert macrocycle with 20 equivalent fluorine nuclei having a single resonance at −92.5 ppm. This molecule satisfies most of the theoretical 19F MRI reagent design criteria (i and ii). Oxygen tightly coordinates with PCE, forming a complex that is detectable by mass spectrometry43 and significantly shortens the 19F T1. This effect has been exploited in local oxygen sensing studies in tumors44–46 and in the brain.47 PCE was also used for MRI detection of atherosclerosis in animal models39 and for in vivo cell tracking.17,34,48

Recently, PFPE (Figure 1(d)), a linear perfluoropolyether polymer, was introduced to meet all of the above design criteria (i–iii) for a 19F MRI cell tracking reagent.22,49 The linear PFPE has a simple 19F NMR spectrum22,34,50 with >40 equivalent fluorines from CF2CF2O monomer repeats and the major resonance is close to that of PCE (−91.5 ppm). Linear PFPEs, as well as PCE, are synthesized from analogue hydrocarbons by direct fluorination.50,51. Recently, linear PFPE was first used for 19F cell tracking and quantification in vivo in a mouse diabetes model.22

Fluorous phase synthetic approaches47,52 take advantage of linear PFCs tendency to behave as their own liquid phase when mixed with water, lipids or organic solvents.26 Recently, fluorous phase synthetic strategies were used for chemical modification of linear PFPEs resulting in fluorescent ‘blended’ PFPE amides34 (FBPAs, Figure 2(e)). The conjugation approach exploits the high reactivity of PFPE alkyl esters (Figure 2(d), where R = C(O)OMe) to nucleophilic addition of primary or secondary amines.53 Fluorescent dye is directly conjugated to PFPE via aliphatic amino linker, and unconjugated dye is removed by fluorous phase liquid-liquid extraction.34 FBPAs behave as a unique fluorous oil phase during nanoemulsion formulation and retain their fluorescent properties in vivo.34 Application of FBPAs to cell tracking and 19F MRI is discussed in Section 4.

PFC NANOEMULSION FORMULATION FOR CELL LABELING

PFCs do not mix with cell membranes and would not enter cells unless formulated into a biocompatible nanoemulsion or microemulsion. A significant body of work on formulating stable nanoemulsions has been reported in the context of developing vascular imaging agents or artificial blood substitutes.23,26,54 In these applications, nanoemulsions have to be highly stable in vascular circulation for many hours. The surfactants used in these types of formulations should promote stability in the blood stream and possibly passive or active targeting to macrophages in situ. However, these are not necessarily desirable design features for PFC nanoemulsions used in ex vivo cell labeling.

A PFC nanoemulsion for cell tracking must efficiently and safely label target cells ex vivo before administering to the subject by injection. Empirically, safe loading levels of PFC are found to be on the order of 1011–1012 fluorine atoms per cell without overt toxicity.22,34,48,49 Ideally, a nanoemulsion for 19F MRI cell tracking using ex vivo labeling should satisfy the following design criteria: (1) small droplet size, ideally <200 nm, (2) low polydispersity index (PDI), ideally less than 0.2, (3) maximum fluorine-to-surfactant ratio in order to minimize the amount of MRI-inactive material delivered inside the cell, (4) a surface that promotes cell membrane interaction and/or cellular uptake, (5) long-term intracellular retention for longitudinal MRI tracking, (6) long shelf-life, ideally >1 year, (7) low toxicity to cells and tissues, (8) does not modify phenotype, morphology or biological function of the labeled cells, and (9) PFC nanoemulsions should be able to label a wide range of cell types.

PFC Nanoemulsions

Nanoemulsions are kinetically stable emulsions with a droplet size typically between 20 and 500 nm. Unlike microemulsions, which can form spontaneously, nanoemulsions require high energy processing, such as high pressure, high shear homogenization (e.g., microfluidization)55 or sonication. Nanoemulsion formation usually does not require high amounts of surfactant and can be stabilized by steric effects.56 The most common degradation mechanism for nanoemulsions is Ostwald ripening, a molecular diffusion phenomena that results in a gradual growth of the larger particles at the expense of smaller ones.56,57 Nanoemulsion degradation via Ostwald ripening represents a major problem in formulating stable PFC nanoemulsions.58–60 The choice of surfactant, emulsification technique and PFC structure can significantly slow down but cannot fully prevent Ostwald ripening. PFC structure significantly affects the Ostwald ripening rate.58,60 A recent study has shown that perfluorodecalin (Figure 2(c)) forms smaller nanoemulsion droplets and exhibits a lower droplet growth rate due to Ostwald ripening then n-perfluorohexane.58 Molecular diffusion is more likely to occur in n-perfluorohexane then in perfluorodecaline emulsions and can be associated with the larger solubility and diffusion coefficients of n-perfluorohexane in external phase. These findings are directly relevant to hydrocarbon nanoemulsion degradation studies, where the molar volume of the hydrocarbon inversely correlates to the nanoemulsion degradation rate.61 Branched and longer chain PFCs give more stable emulsions under the same conditions compared to short chain PFCs. Kabalnov60 suggests that the emulsion stability depends, to a larger extent, on the perfluorocarbon structure rather than the emulsifier. However, this is far from being a rule and surfactants can play a significant role in emulsion stability. Possible methods to decrease Ostwald ripening, for example, include the addition of water-insoluble oils such as a long triglyceride to the nanoemulsion62 or the use of longer chain perfluorocarbons.63

Emulsifiers and Surfactants for PFC Nanoemulsions

In addition to the PFC structure, the choice of appropriate emulsifier is of great importance to stabilize the nanoemulsion and to render it biocompatible. Suitable emulsifiers for preparing nanoemulsions for cell labeling must be non-toxic, chemically stable, and help to reduce the characteristically large interfacial tension of perfluorocarbons in the aqueous phase. Only a few surfactants and emulsifiers have been proven successful in stabilizing PFC colloid dispersions in water. Below, we discuss the most commonly employed emulsifiers for preparing PFC nanoemulsions suitable for MRI. Phospholipids (e.g., egg yolk phospholipids, EYP) and pluronics (e.g., poloxamer 188 or F68) are the most common emulsifiers.23 The addition of a fluorinated surfactant to stabilize the nanoemulsion has also been suggested.60 However, this approach is not suitable for stabilizing 19F MRI reagents, due to the potential for chemical shift artifacts caused by the fluorine in the surfactant molecules.

Lipids

One approach to formulate stable PFC nanoemulsions utilizes lipids and organic oils. Researchers have developed a PFOB nanoemulsions that were found to be useful in both ultrasound and MRI.17,18,64,65 These PFOB nanoemulsions used safflower oil and a lecithin-containing surfactant co-mixture. The nanoemulsion satisfied two requirements for stability: first, the emulsifiers were lipids, and based on Kabalnov,60 the PFC nanoemulsions prepared with lipids are more stable, and second, the added safflower oil decreases the Ostwald ripening, as a hydrophobic additive. The resulting nanoemulsion had a low droplet size (224 nm) and a high PDI of 0.350, which is consistent with earlier findings58,62 that lipid based perfluorocarbon nanoemulsions contain heterogeneous droplet diameters. The same emulsification method was used to prepare PCE nanoemulsion, which resulted in similar droplet size (233 nm) and a significantly lower PDI (0.170). This shows that PFC structure does not have substantial effect on droplet size, but affects the nanoemulsion droplet PDI.

Non-ionic surfactants

One of earliest reported PFC nanoemulsion surfactants was Pluronic F68™(BASF).24 This molecule is a poly(ethylene oxide)–poly(propylene oxide)–poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO–PPO–PEO) tri-block non-ionic copolymer that is FDA approved for human use. F68 stabilizes the PFC oil droplets in aqueous phase mostly by steric effects.66 Previous structural studies have shown that block polymers adsorb onto the interface between the colloid PFC and the aqueous phase and that this adsorption is dependent on the electrolyte concentration in the solution.67–69

Recent studies describe the development of a novel, highly stable nanoemulsion prepared with linear PFPE, pluronic F68 and linear short chain polyethylenimine (PEI).34 Figure 3(b) shows 125 day stability data by dynamic light scattering (DLS) at three different temperatures, and no change in nanoemulsion droplet size or PDI was observed. Further testing showed no signs of Ostwald ripening up to 14 months of follow up (data not shown). In this example we speculate that the high molecular weight linear PFPE is responsible for high nanoemulsion stability from Ostwald ripening degradation, aided by steric stabilization from the F68.

FIGURE 3.

DLS analysis of a linear PFPE nanoemulsion emulsified with F68 and PEI. Panel A displays the diameter distribution by light intensity, and B shows the diameter and PDI (error bars) followed over time at three different storage temperatures: 4 (■), 25 (●), and 37 (▼) °C. (Adapted from Ref 34).

IN VIVO 19F MRI AND CELL TRACKING

Cell tracking by 19F MRI has the potential to accelerate studies of inflammation and regenerative medicine because it is non-invasive and has high specificity. Previously, 19F MRI of PFCs has been used for several, mostly extracellular applications.35,70–71 Various types of PFCs have long been contemplated25 as oxygen carriers during surgery and as artificial blood substitutes,71 and thus a large volume of data exists on the toxicity profile and clearance pathways of these materials. In the above examples large doses of PFC are delivered intravenously. In contrast, 19F cell tracking applications using ex vivo cell labeling uses only a comparatively miniscule mass of the PFC agents (i.e., contained within the transferred cells).

PFC acts like a ‘tracer’ agent, and 19F magnetic resonance directly detects the density of 19F spins (nuclei) contained in the PFC droplets located inside the cells, which is generally of low concentration compared to the 1H nuclei contained in the ~50 M mobile water. Thus, the signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR) of the 19F images will be significantly lower than that commonly observed for 1H MRI. Paramount, however, is that one does not demand a high 19F SNR. Because there is negligible 19F background, any 19F signal detected is from labeled cells. Unlike 1H anatomical imaging, where one relies on a high SNR to resolve detailed anatomy and organ definition, the 19F image only needs to detect localized pools of cells at arbitrarily low SNR; the 1H image overlay provides the detailed anatomical context.

The ultimate sensitivity of the 19F MRI cell detection technique is not yet known and certainly depends on many technical details, such as the cell type, subject, and the imaging system used. From basic principles, it is straightforward to perform a ‘back of the envelope’ calculation of the practical limits of the number of PFC-labeled cells per voxel that can be detected. This is very conservatively estimated to be ~105 cells per voxel using a conventional 1.5T clinical scanner.19 Empirical MRI phantom studies show that one can detect ~7,500 labeled T cells per voxel using in vivo-like acquisition parameters in a high-field MRI system.22 Overall, we believe the practical cell detection sensitivity is on the order of 104–105 cells per voxel clinically. In high field animal scanners, the sensitivity will be better than 104 cells per voxel. Recent studies from Washington University17 support this view, where they imaged PFC-labeled stem cells implanted in a rodent on a 1.5T scanner in a short scan time (~7 min). Single cell imaging is not possible with the PFC labeling, as has been reported by several groups using SPIO agents.72,73 More importantly, MRI applied to cell tracking problems will demand unambiguous identification and robust quantification of regions where thousands of cells cluster. Overall, work remains to optimize the 19F MRI acquisition schemes for cell tracking.

Ideally PFC nanoemulsions can label a wide range of cell types causing no toxicity, or changes in phenotype, morphology or function, while providing sufficient intracellular 19F signal for MRI. Recent reports utilize PCE17,19 and PFOB nanoemulsions17 for cell tracking by 19F MRI. Cellular uptake mechanisms of PFC nanoemulsions have yet to be studied in detail. Our lab originally used19 a PCE lipid based nanoemulsion with a commercially available cationic lipid transfection reagent, achieving sufficient cell loading and adequate 19F MRI signal in vivo (Figure 4). In these studies, transmission electron microscopy shows nanoemulsion droplets as low-electron density spheroids within compartments consistent with vessicles.

FIGURE 4.

In vivo MRI using PFC with dendritic cells (DCs) in mouse. Images of the labeled cells (i.e., 19F images) are displayed on a ‘hot-iron’ intensity scale, and the anatomical (1H) images are shown in grayscale. The three panels on the far left are a mouse quadriceps after intramuscular injection of DCs (asterisk indicates injection site). (a) 19F and 1H images (from left to right) and a ‘composite’ 19F/1H image. (b) The composite image of DC migration into the popliteal lymph node following a hind foot pad injection. (c) Composite image through the torso following intravenous inoculation with labeled DCs. Cells are apparent in the liver, spleen, and weakly in the lungs. (Data taken from Ref 19).

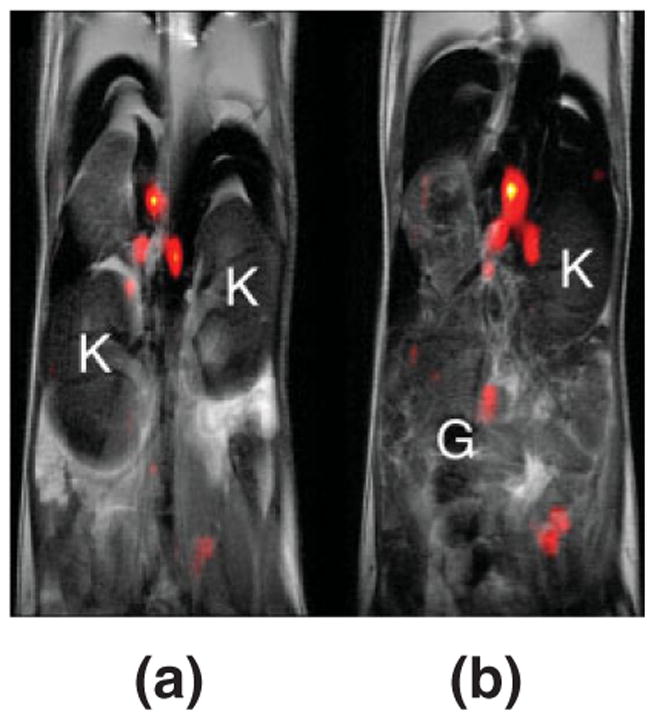

More recent studies34 report ‘self-delivering’ nanoemulsions that efficiently label non-phagocytic and phagocytic cells without the need of transfection reagents. The linear PFPE nanoemulsion labeled primary T cells while retaining their phenotype and were successfully imaged in vivo (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

In vivo MRI of labeled T cells in the mouse model. The 19F image (pseudo-color) shows a localized accumulation of T cells labeled with PFPE nanoemulsion in lymph nodes and the grayscale underlay is an anatomical 1H image. Panels (a) and (b) display two consecutive 2 mm thick slices through the torso, and for anatomical orientation the kidneys (K) and gut (G) are noted. During imaging, the mouse was anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine cocktail, connected to a mechanical ventilation apparatus, acquisitions were cardio-respiratory gated, and body temperature was regulated at 37°C. Data were collected for both 19F and 1H in a single imaging session. (Adapted from Ref 34).

In vivo 19F MRI cell tracking is often not sufficient to follow cellular fate and cellular phenotype post-transfer. A dual fluorescent-MRI cellular labeling reagent is highly desirable for recovery and further study of cells post-imaging. The fluorescent moiety facilitates unambiguous identification and recovery of labeled cells from tissues. Fluorescence-based detection techniques (e.g., microscopy and immuno-cytochemistry) can provide confirmation of the MRI cell tracking results in bioposied tissues. One such reagent was developed recently, where linear PFPEs were conjugated directly to fluorescent dyes.34 Following the in vivo imaging, fluorescence microscopy and FACS analysis were performed on the labeled T cells. Figure 6 shows confocal microscopy of labeled DCs and T cells with BODIPy-TR PFPE nanoemulsion. These new dual mode reagents open new avenues for imaging as well, including, for example, the use of live animal fluorescence imaging.

FIGURE 6.

Dual-mode reagents for 19F MRI and fluorescent detection. Confocal microscopy of (a) labeled mouse DCs (b) and primary T cells labeled with FBPA (red). (Adapted from Ref 34).

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In this review we have discussed the overall usefulness of PFC nanoemulsions as reagents for 19F cell tracking. We described the design and preparation of these reagents through specific examples reported to date. Introducing additional imaging and detection modalities to PFC nanoemulsions opens new avenues for MRI cell tracking and promises to vastly improve current technology. Although the biomedical application of these new technologies are still nascent, we believe that in the future it will be possible to translate 19F cell tracking into the clinical arena.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, et al. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(14):889–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterson L, Minas T, Brittberg M, Nilsson A, Sjogren-Jansson E, et al. Two- to 9-year outcome after autologous chondrocyte transplantation of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat R. 2000;374:212–223. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200005000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjorklund A, Lindvall O. Cell replacement therapies for central nervous system disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2000;6(3):537–544. doi: 10.1038/75705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashley DM, Faiola B, Nair S, Hale LP, Bigner DD, et al. Bone marrow-generated dendritic cells pulsed with tumor extracts or tumor RNA induce antitumor immunity against central nervous system tumors. J Exp Med. 1997;186(7):1177–1182. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilboa E, Nair SK, Lyerly HK. Immunotherapy of cancer with dendritic-cell-based vaccines. Cancer Immunol Immun. 1998;46(2):82–87. doi: 10.1007/s002620050465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh TC, Zhang W, Ildstad ST, Ho C. Intracellular labeling of T-cells with superparamagnetic contrast agents. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30(5):617–625. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewin M, Carlesso N, Tung CH, Tang XW, Cory D, et al. Tat peptide-derivatized magnetic nanoparticles allow in vivo tracking and recovery of progenitor cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(4):410–414. doi: 10.1038/74464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoehn M, Kustermann E, Blunk J, Wiedermann D, Trapp T, et al. Monitoring of implanted stem cell migration in vivo A highly resolved in vivo magnetic resonance imaging investigation of experimental stroke in rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(25):16267–16272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242435499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahrens ET, Feili-Hariri M, Xu H, Genove G, Morel PA. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of iron-oxide particles provides efficient labeling of dendritic cells for in vivo MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(6):1006–1013. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kircher MF, Allport JR, Graves EE, Love V, Josephson L, et al. In vivo high resolution three-dimensional imaging of antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte trafficking to tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63(20):6838–6846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulte JWM, Arbab AS, Douglas T, Frank JA. Preparation of magnetically labeled cells for cell tracking by magnetic resonance imaging. Methods Enzymol. 2004;386:275–299. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)86013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corot C, Robert P, Idée JM, Port M. Recent advances in iron oxide nanocrystal technology for medical imaging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58(14):1471–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho C, Hitchens TK. A non-invasive approach to detecting organ rejection by MRI: Monitoring the accumulation of immune cells at the transplanted organ. Curr Pharm Biotechno. 2004;5(6):551–566. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinschnitz C, Bendszus M, Frank M, Solymosi L, Toyka KV, et al. In Vivo Monitoring of macrophage infiltration in experimental ischemic brain lesions by magnetic resonance imaging. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23(11):1356–1136. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000090505.76664.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulte JWM, Frank JA, Dousset V. Imaging macrophage activity in the brain by using ultrasmall particles of iron oxide [2] (multiple letters) Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(9):1767–1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu S, Jordan EK, Brocke S, Bulte JWM, Quigley L, et al. Study of relapsing remitting experimental allergic encephalomyelitis SJL mouse model using MION-46L enhanced in vivo MRI: early histopathological correlation. J Neurosci Res. 1998;52(5):549–558. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980601)52:5<549::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Partlow KC, Chen J, Brant JA, Neubauer AM, Meyerrose TE, et al. $19$F magnetic resonance imaging for stem/progenitor cell tracking with multiple unique perfluorocarbon nanobeacons. FASEB J. 2007;21(8):1647–1654. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6505com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanza GM, Winter PM, Neubauer AM, Caruthers SD, Hockett FD, et al. 1H/19F magnetic resonance molecular imaging with perfluorocarbon nanoparticles. In: Ahrens ET, editor. In vivo cellular and molecular imaging. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 58–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahrens ET, Flores R, Xu H, Morel PA. In vivo imaging platform for tracking immunotherapeutic cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(8):983–987. doi: 10.1038/nbt1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nöth U, Morrissey SP, Deichmann R, Jung S, Adolf H, et al. Perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether labelled macrophages in adoptive transfer experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Artif Cell Blood Sub. 1997;25(3):243–254. doi: 10.3109/10731199709118914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flögel U, Ding Z, Hardung H, Jander S, Reichmann G, et al. In vivo monitoring of inflammation after cardiac and cerebral ischemia by fluorine magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2008;118(2):140–148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srinivas M, Morel PA, Ernst LA, Laidlaw DH, Ahrens ET. Fluorine-19 MRI for visualization and quantification of cell migration in a diabetes model. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(4):725–734. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riess JG. Oxygen carriers (“blood substitutes”)—raison d’etre, chemistry, and some physiology. Chem Rev. 2001;101(9):2797–2919. doi: 10.1021/cr970143c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharts CM, Reese HR. The solubility of oxygen in aqueous fluorocarbon emulsions. J Fluo Chem. 1978;11(6):637–641. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leland C, Clark J, Gollan F. Survival of mammals breathing organic liquids equilibrated with oxygen at atmospheric pressure. Science. 1966;152(3730):1755–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3730.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krafft MP, Riess JG. Perfluorocarbons: life sciences and biomedical uses dedicated to the memory of Professor Guy Ourisson, a true RENAISSANCE man. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2007;45(7):1185–1198. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krafft MP, Chittofrati A, Riess JG. Emulsions and microemulsions with a fluorocarbon phase. Curr Op Coll Inter Sci. 2003;8(3):251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krafft MP. Fluorocarbons and fluorinated amphiphiles in drug delivery and biomedical research. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47(2–3):209–228. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castro O, Nesbitt AE, Lyles D. Effect of a perfluorocarbon emulsion (Fluosol-Da) on reticuloendothelial system clearance function. Am J Hematol. 1984;16(1):15–21. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HK, Nalcioglu O, Buxton RB. Correction for chemical-shift artifacts in 19F imaging of PFOB: simultaneous multislice imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1991;21(1):21–29. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910210105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Busse LJ, Pratt RG, Thomas SR. Deconvolution of chemical shift spectra in two- or three-dimensional 19F MR imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1988;12(5):824–835. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198809010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimura A, Narazaki M, Kanazawa Y, Fujiwara H. 19F magnetic resonance imaging of perfluorooctanoic acid encapsulated in liposome for biodistribution measurement. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22(6):855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarz R, Schuurmans M, Seelig J, Künnecke B. 19F-MRI of perfluorononane as a novel contrast modality for gastrointestinal imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(1):80–86. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199901)41:1<80::aid-mrm12>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janjic JM, Srinivas M, Kadayakkara DKK, Ahrens ET. Self-delivering nanoemulsions for dual fluorine-19 MRI and fluorescence detection. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(9):2832–2841. doi: 10.1021/ja077388j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratner AV, Hurd R, Muller HH, Bradley-Simpson B, Pitts W, et al. 19F magnetic resonance imaging of the reticuloendothelial system. Magn Reson Med. 1987;5(6):548–554. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910050605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laukemper-Ostendorf S, Scholz A, Bürger K, Heussel CP, Schmittner M, et al. 19F-MRI of perflubron for measurement of oxygen partial pressure in porcine lungs during partial liquid ventilation. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(1):82–89. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shukla HP, Mason RP, Bansal N, Antich PP. Regional myocardial oxygen tension: 19F MRI of sequestered per-fluorocarbon. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35(6):827–833. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ratner AV, Muller HH, Bradley-Simpson B, Hirst D, Pitts W, et al. Detection of acute radiation damage to the spleen in mice by using fluorine-19 MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151(3):477–480. doi: 10.2214/ajr.151.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morawski AM, Winter PM, Yu X, Fuhrhop RW, Scott MJ, et al. Quantitative “magnetic resonance immuno-histochemistry” with ligand-targeted F-19 nanoparticles. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(6):1255–1262. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellena JF, Obraztsov VV, Cumbea VL, Woods CM, Cafiso DS. Perfluorooctyl bromide has limited membrane solubility and is located at the bilayer center. Locating small molecules in lipid bilayers through paramagnetic enhancements of NMR relaxation. J Med Chem. 2002;45(25):5534–5542. doi: 10.1021/jm020278x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas SR, Pratt RG, Millard RW, Samaratunga RC, Shiferaw Y, et al. In vivo pO2 imaging in the porcine model with perfluorocarbon F-19 NMR at low field. Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;14(1):103–114. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(95)02046-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sotak CH, Hees PS, Huang HN, Hung MH, Krespan CG, et al. A new perfluorocarbon for use in fluorine-19 magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29(2):188–195. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brodbelt J, Maleknia S, Liou CC, Lagow R. Selective formation of molecular oxygen/perfluoro crown ether adduct ions in the gas phase. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113(15):5913–5914. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mason RP, Hunjan S, Le D, Constantinescu A, Barker BR, et al. Regional tumor oxygen tension: fluorine echo planar imaging of hexafluorobenzene reveals heterogeneity of dynamics. Int J Radioat Oncol. 1998;42(4):747–750. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNab JA, Yung AC, Kozlowski P. Tissue oxygen tension measurements in the Shionogi model of prostate cancer using 19F MRS and MRI. Magn Reson Mat Phys Biol Med. 2004;17(3–6):288–295. doi: 10.1007/s10334-004-0083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helmer KG, Han S, Sotak CH. On the correlation between the water diffusion coefficient and oxygen tension in RIF-1 tumors. NMR Biomed. 1998;11(3):120–130. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199805)11:3<120::aid-nbm506>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duong TQ, Iadecola C, Kim SG. Effect of hyperoxia, hypercapnia, and hypoxia on cerebral interstitial oxygen tension and cerebral blood flow. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45(1):61–70. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200101)45:1<61::aid-mrm1010>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahrens ET. Cellular labeling for nuclear magnetic resonance techniques. 2005 WO2005072780. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srinivas M, Turner MS, Janjic JM, Morel PA, Laidlaw DH, Ahrens ET. In vivo cytometry of antigen specific T-cells using 19F MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22063. to appear. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerhardt GE, Lagow RJ. Synthesis of the perfluoropoly(ethylene glycol) ethers by direct fluorination. J Org Chem. 1978;43(23):4505–4509. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin TY, Lin WH, Clark WD, Lagow RJ, Larson SB, et al. Synthesis and chemistry of perfluoro macrocycles. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116(12):5172–5179. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Studer A, Hadida S, Ferritto R, Kim SY, Jeger P, et al. Fluorous synthesis: a fluorous-phase strategy for improving separation efficiency in organic synthesis. Science. 1997;275(5301):823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5301.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tonelli C, Gavezotti P, Strepparola E. Linear per-fluoropolyether difunctional oligomers: chemistry, properties and applications. J Fluor Chem. 1999;95(1–2):51–70. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lowe KC. Engineering blood: synthetic substitutes from fluorinated compounds. Tissue Eng. 2003;9(3):389–399. doi: 10.1089/107632703322066570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jafari SM, He Y, Bhandari B. Nano-emulsion production by sonication and microfluidization–a comparison. Intern J Food Prop. 2006;9(3):475–485. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tadros T, Izquierdo P, Esquena J, Solans C. Formation and stability of nano-emulsions. Adv Colloid Interfac. 2004;108–109:303–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor P. Ostwald ripening in emulsions. Adv Colloid Interfac. 1998;75(2):107–163. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8686(03)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freire MG, Dias AMA, Coelho MAZ, Coutinho JAP, Marrucho IM. Aging mechanisms of perfluorocarbon emulsions using image analysis. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2005;286(1):224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Postel M, Riess JG, Weers JG. Fluorocarbon emulsions–the stability issue. Artif Cell Blood Sub. 1994;22(4):991–1005. doi: 10.3109/10731199409138797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kabalnov AS, Shchukin ED. Ostwald ripening theory. Applications to fluorocarbon emulsion stability. Adv Colloid Interfac. 1992;38(C):69–97. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weiss J, Herrmann N, McClements DJ. Ostwald ripening of hydrocarbon emulsion droplets in surfactant solutions. Langmuir. 1999;15(20):6652–6657. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weers JG, Arlauskas RA, Tarara TE, Pelura TJ. Characterization of fluorocarbon-in-water emulsions with added triglyceride. Langmuir. 2004;20(18):7430–7435. doi: 10.1021/la049375e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.MarieBertilla S, Thomas JL, Marie P, Krafft MP. Cosurfactant effect of a semifluorinated alkane at a fluorocarbon/water interface: impact on the stabilization of fluorocarbon-in-water emulsions. Langmuir. 2004;20(10):3920–3924. doi: 10.1021/la036381m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lanza GM, Wallace KD, Scott MJ, Cacheris WP, Abendschein DR, et al. A novel site-targeted ultrasonic contrast agent with broad biomedical application. Circulation. 1996;94(12):3334–3340. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lanza GM, Yu X, Winter PM, Abendschein DR, Karukstis KK, et al. Targeted antiproliferative drug delivery to vascular smooth muscle cells with a magnetic resonance imaging nanoparticle contrast agent: Implications for rational therapy of restenosis. Circulation. 2002;106(22):2842–2847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044020.27990.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsu L-C, Creech J, Zalesky P, Kivinski M. Perfluorocarbon emulsions witt non-fluorinated surfactants. 2004 US2004057906. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Washington C, King SM. Effect of electrolytes and temperature on the structure of a poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide)-poly(ethylene oxide) block copolymer adsorbed to a perfluorocarbon emulsion. Langmuir. 1997;13(17):4545–4550. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Washington C, King SM, Attwood D, Booth C, Mai SM, et al. Polymer bristles: adsorption of low molecular weight poly(oxyethylene)-poly(oxybutylene) diblock copolymers on a perfluorocarbon emulsion. Macromolecules. 2000;33(4):1289–1297. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Washington C, King SM, Heenan RK. Structure of block copolymers adsorbed to perfluorocarbon emulsions. J Phys Chem. 1996;100(18):7603–7609. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meyer KL, Joseph PM, Mukherji B, Livolsi VA, Lin R. Measurement of vascular volume in experimental rat tumors by 19F magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 1993;28(8):710–709. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199308000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cohn SM. Oxygen therapeutics in trauma and surgery. J Trauma. 2003;54(5):193–198. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000047228.46099.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu YL, Ye Q, Foley LM, Hitchens TK, Sato K, et al. In situ labeling of immune cells with iron oxide particles: an approach to detect organ rejection by cellular MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(6):1852–1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507198103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shapiro EM, Sharer K, Skrtic S, Koretsky AP. In vivo detection of single cells by MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(2):242–249. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]