Abstract

This study examined the interrelations between parental relationships, romantic relationships, and antisocial behavior among female and male juvenile delinquents. Participants from a diverse sample of 1,354 adolescents (14–17 years) adjudicated of a serious (i.e. felony) offense were matched based on age, race, and committing offense, yielding a sample of 184 girls matched with 170 boys. Results indicate that while female offenders are more likely to date boys 2 years their senior, age difference alone is not directly related to self-reported offending. Instead, findings suggest that girls who engage in self-reported delinquent behavior are more likely to experience a high degree of antisocial encouragement exerted on them by their current romantic partner. Interestingly, this relation varies with the quality (warmth) of parental relationships and the romantic partner's level of antisocial encouragement, with the association between partner encouragement and self-reported offending being strongest among youths reporting warm relationships with their opposite-sex parent.

It is well established that males engage in more delinquent and criminal acts than females (for a review, see Dodge, Coie, & Lynam 2006). While the gender gap in offending has shrunk considerably, with females becoming more frequent and possibly more aggressive in their offenses (Snyder, 2004), the etiology of delinquency for girls is still uncertain. There is reason to believe, for example, that the causes of delinquency may be more relationship-oriented for girls than for boys (Odgers & Moretti, 2002), and research has found that female delinquency is often associated with adversarial relationships with parents and romantic partners (National Mental Health Association, 2005). Unfortunately, little is known about the interrelations between romantic relationships, parental relationships, and antisocial behavior among juvenile delinquents, particularly females. The goal of the present study is to examine these associations.

The average adolescent begins to date around 13 or 14 years of age (Feiring, 1993), and these relationships are less transitory than commonly perceived: 35% of 15–16-year-olds and almost 60% of 17–18-year-olds say that their relationships have lasted 11 months or more. In fact, romantic relationships are a normative part of adolescent development (Collins, 2003) and are especially salient for girls' psychological development from childhood through adolescence (Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003). Research suggests that females are more likely than males to derive their sense of self as well as other psychologically relevant information from these interpersonal relationships (Maccoby, 1990). Typically, adolescent females are more likely than their male counterparts to date older partners, whereas males date same-age or younger partners (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003). Adolescence is also a normative period for the development of sexuality (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2004) with more than half of all teenagers engaging in sexual intercourse before graduating from high school (Sonenstein, Ku, Lindberg, Turner, & Pleck, 1998). However, among sexually active adolescents, casual sex is not uniformly preferred (Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1994) and fidelity is viewed as an important element of a sexual relationship (Arnett, 2002).

While romantic relationships during adolescence have the potential to affect development positively (Furman & Shaffer, 2003), dating has also been linked to negative outcomes. For example, greater dating experience (i.e., romantic involvement with one or more partners continuously or intermittently; Meeus, Branje, & Overbeek, 2004) and more romantic partners (Zimmer-Gembeck, Siebenbruner, & Collins, 2001) were significantly associated with increased delinquent behaviors during adolescence. Early and intensive dating (i.e., becoming seriously involved before age 15) has been linked with increased alcohol use and delinquency (Davies & Windle, 2000). Moreover, girls, more so than boys, are strongly influenced by their romantic partners. For example, a romantic partner's serious delinquency (e.g., stealing, burglary, fighting) influences girls more than boys to engage in minor deviance (Haynie, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2005). There is also evidence suggesting possible risks associated with girls' romantic involvement with older boyfriends. For example, Mezzich et al. (1997) report that girls' affiliation with an older boyfriend is associated with increased substance use. Other studies show that girls with older boyfriends are more likely to engage in all forms of sexual intimacy, to have sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and to experience sexual coercion (Gowen, Feldman, Diaz, & Yisrael, 2004; Marín, Coyle, Gómez, Carvajal, & Kirby, 2000).

Interestingly, juvenile offenders approach dating somewhat differently than do their prosocial counterparts. In longitudinal studies, antisocial girls and boys typically sought out romantic partners who were also involved in criminal behavior (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997; Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter, & Silva, 2001) and sanctioned antisocial behavior by a partner (Moffitt et al., 2001). The persistence of antisocial behavior and poor psychosocial adjustment into young adulthood (age 21) occurred only among girls with antisocial boyfriends (Moffitt et al., 2001).

Relationships with romantic partners and with parents can influence the likelihood of delinquent behavior, but these effects are not entirely independent, since there is ample reason to expect that the quality of parent–adolescent relationships influences the stability and quality of the adolescent's romantic relationships (Collins & Sroufe, 1999; Conger, Cui, Bryant, & Elder, 2000). Other research indicates that negative emotionality (e.g., anger, ambivalence) in parent–adolescent dyads is predictive of poor quality interactions with romantic partners in late adolescence (Kim & Capaldi, 2004). According to Meeus et al. (2004) parental influence on adolescent offending is strongest when the adolescent has no intimate partners; for youth who consistently had a romantic partner over their 6-year longitudinal study, parental support was not associated with delinquency. The available data, however, are insufficient to determine with any precision whether romantic partner characteristics mediate the link between the parent–adolescent relationship and delinquent behavior or whether the roles of paternal and maternal support differ. Collins (2003) calls for researchers to investigate interconnections between these significant social influences on adolescents' developmental outcomes.

Clearly, it is important to examine female delinquency within the context of significant interpersonal relationships. Given that the majority of literature to date has focused on understanding the male delinquent, the present study investigates the associations between parent and partner relationships and delinquency for females and compares them with males. Specifically, we examine (a) the general characteristics and qualities of romantic partner relationships, (b) the partner characteristics and qualities that are associated with antisocial behavior, and finally (c) the interrelations between maternal and paternal relationship characteristics, partners' antisocial encouragement, and antisocial behavior. We hypothesize that the type of partner one dates (particularly the partner's level of antisocial encouragement) will be more strongly related to antisocial behavior than the general characteristics of the partner (e.g., age difference). We further expect that adolescents with “good” (more connected and less hostile) relationships with their parents will tend to be involved in “good” (less antisocially encouraging) romantic relationships, and that good parental relationships will moderate the relation between partner antisocial encouragement and offending behavior.

METHOD

Participants were enrolled in the Pathways to Desistance study (see Mulvey et al., 2004). Complete details of the study methodology and recruitment procedures are provided in Schubert et al. (2004). The following is a summary of that description as it pertains to the present analysis.

Participants

Data for the present analyses were obtained from a sample of 1,354 adolescents (1,170 males and 184 females) participating in a prospective study of serious juvenile offenders in two major metropolitan areas. The enrolled adolescents were between 14 and 17 years of age and had all been adjudicated of a serious criminal offense. Because we are interested in comparing females with males, we selected a matched group of males to compare with the smaller number of females enrolled in the study. Matching was based on age, race, and committing offense, and resulted in 170 boys matched with the girls, for a total sample of 354 (all of the girls remain in the analyses as they are the focus of this paper). The subsample is similar to the overall sample, in that subjects are predominantly lower-class, with fewer than 5% of the participants from households headed by a 4-year college graduate and 51% of the households headed by a parent with less than a high-school education. Thirty-seven percent of the participants were African American, 31% Hispanic American, 27% non-Hispanic Caucasian, and 5% other.

Procedures

The juvenile court provided the names of eligible youths for enrollment in the study based on their age and adjudicated charge. Interviewers attempted to contact each eligible juvenile and his or her parent or guardian to ascertain the juvenile's interest in participating in the study and to obtain parental consent. Once the appropriate consents had been obtained, interviews were conducted in a facility (if the juvenile was confined), at the juvenile's home, or at a mutually agreed-upon location in the community.

The initial interview was administered over 2 days in two 2-hour sessions. Interviewers and participants sat side-by-side facing a computer, and questions were read aloud to avoid any problems caused by reading difficulties. Respondents would generally answer the interview questions out loud, although for questions concerning sensitive material (e.g., criminal behavior, drug use), respondents were encouraged to use a portable keypad to input their answers privately. When interviews were conducted in participants' homes or in community settings, attempts were made to conduct them out of the earshot of other individuals. Participants were informed that we had a requirement for confidentiality placed upon us by the U.S. Department of Justice that prohibited our disclosure of any personally identifiable information to anyone outside the research staff, except in cases of suspected child abuse or where an individual was believed to be in imminent danger.

Measures

Offending behavior

Antisocial and illegal activities were measured by an adaptation of the Self-Report of Offending Scale (SRO; Huizinga, Esbensen, & Weihar, 1991). The SRO consists of 22 yes-or-no items which elicit subject involvement in different types of crime in the past 6 months, with higher scores indicating participation in more types of delinquent behavior (α = .88).

Romantic relationships

Participants were asked eight general questions about their dating history (e.g., number of romantic partners, age of first sexual intercourse) and six specific questions about their current relationship in the past 6 months (e.g., age of current romantic partner, length of time in relationship, etc.). To assess delinquent pressure within the relationship, questions about the amount of antisocial encouragement exerted by the partner were included (seven items, e.g., “Has [Name] suggested that you should steal something?”; α = .68). Higher scores indicate more antisocial encouragement.

Parent–adolescent relationships

The Quality of Parental Relationships Inventory (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994) was adapted for this study to assess the affective tone of the parent–adolescent relationship. The 42 items from the measure tap maternal warmth (9 items, e.g., “How often does your mother let you know she really cares about you?”, α = .92), maternal hostility (12 items, e.g., “How often does your mother get angry at you?”, α = .85), paternal warmth (9 items, e.g., “How often does your father tell you he loves you?”, α = .95), and paternal hostility (12 items, e.g., “How often does your father throw things at you?”, α = .88). Participants respond on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “Never” to “Always,” with higher scores on each scale indicating more warmth or more hostility, respectively.

RESULTS

Characteristics and Qualities of Romantic Relationships

In order to understand the profile of romantic relationships among juvenile offenders, we compared male and female subjects on their overall dating characteristics. Boys reported more romantic partners (15.4 vs. 8.0) and girls reported a greater length of time in relationships (4.8 vs. 4.4 months), p<.001. In addition, boys reported more “risky” dating behaviors than girls, including earlier age of first intercourse (12.7 vs. 13.7 years), increased likelihood that the first sexual experience was casual (40% vs. 17%), greater number of sexual partners (10.9 vs. 4.6), increased likelihood that they had been unfaithful to a partner (66% vs. 44%), greater number of one-night stands (4.8 vs. 1.1), and greater likelihood of having multiple concurrent sexual partners (51% vs. 17%), all ps<.001.

Boys and girls were also compared on specific characteristics of their current relationships. Girls reported greater age differences with their partner (2.4 vs. 0.3 years), with girls tending to date older boys (18.5 vs. 16.3 years old), p<.001. Boys and girls did not differ in the likelihood of having a current romantic partner, the length of time in their current relationship, or, surprisingly, in their reports of antisocial encouragement exerted by their partner, p>.05.

The Relation Between Romantic Relationship Characteristics and Self-Reported Offending

To examine the relation between romantic relationships and self-reported offending behavior, regression analyses were performed separately for boys and girls. The independent variables were standardized and, due to the nonlinearity of self-reported offending, this variable was recalculated using a square-root transformation. The age difference between the participant and his or her partner and the antisocial encouragement exerted by the partner were entered into the model first, and the interaction between the two was entered second. For girls, only the main effect of antisocial encouragement was significant (β = .43, p<.05), with girls whose boyfriends encourage them to engage in antisocial behavior reporting higher levels of such behavior during the same time period. No significant findings emerged for boys.

Interrelations Among Parental Relations, Romantic Partner Pressure, and Self-Reported Offending

We hypothesized that parental relationship quality would be associated with the likelihood of having an antisocially encouraging romantic partner, and that parental relationship quality would, in addition, moderate the relation between such negative pressures and self-reported offending behavior.

Examination of the correlations between parental relationships and romantic partner antisocial encouragement revealed that the relationship with the opposite-sex parent was most critical. Specifically, for girls, higher levels of romantic partner antisocial encouragement were associated with lower levels of paternal warmth and higher levels of paternal hostility (r = −.21, p = .08; r = .26, p<.05), while for boys, higher levels of romantic partner antisocial encouragement were associated with lower levels of maternal warmth and higher levels of maternal hostility (r = −.33, p<.001; r = .20, p<.05). None of the correlations between romantic partner antisocial encouragement and indicators of parental relationship with same-sex parent were significant, for either boys or girls.

To assess the potential interaction between the quality of the parental relationship and the presence of antisocial encouragement in the romantic relationship on self-reported offending behavior, hierarchical regression analyses were performed within each gender. Specifically, maternal warmth, maternal hostility, antisocial encouragement, and the interactions (Maternal Warmth × Antisocial Encouragement and Maternal Hostility × Antisocial Encouragement) were entered into the model for boys. An analogous model using paternal warmth and hostility was tested for girls. Due to a high occurrence of missing data for father variables (33% of boys and 45% of girls had missing data), boys and girls were compared by matching subjects based on father's presence (yes or no) to ensure that the male and female samples remained comparable. No significant differences were found. Cases without data on this variable were excluded from the analyses.

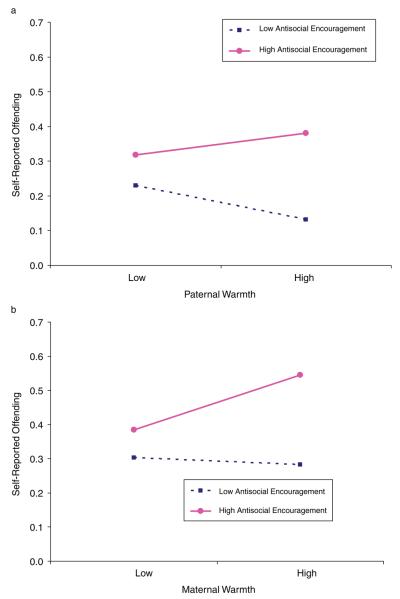

Interesting interactions between partner antisocial encouragement and parental relationships were observed for both boys and girls. Contrary to our expectation, partner antisocial encouragement appeared to have a stronger relation to self-reported offending when parental warmth was high, and a weaker relation when warmth was low. Specifically, for girls, when father warmth was high and partners exhibited more antisocial encouragement, girls were more likely to report having engaged in delinquent acts (β = .38, p = .06; R2 = .10 for Step 1, R2 = .17 for Step 2). Girls were least likely to engage in self-reported delinquency when paternal warmth was high and partner antisocial encouragement was low (see Figure 1a). A similar pattern was observed among boys. Boys in relationships with high levels of antisocial encouragement and high levels of maternal warmth were more likely to report having engaged in delinquent acts (β = −.63, p<.001; R2 = .32 for Step 1, R2 = .51 for Step 2) (see Figure 1b).1 Interactions between partner antisocial encouragement and remaining parental relationship variables were not statistically significant.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Interactive effects of paternal warmth and antisocial encouragement on offending for females. (b) Interactive effects of maternal warmth and antisocial encouragement on offending for males.

DISCUSSION

A number of studies have established links between problem behavior and both parenting style (e.g., Kurdek & Fine, 1994; Steinberg, Blatt-Eisengart, & Cauffman, 2006) and romantic involvement with an antisocial partner (e.g., Meeus et al., 2004; Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2001). The present study builds upon this knowledge base by examining a sample of serious adolescent offenders and by considering the interactions between parental and romantic relationships as correlates of problem behavior, for both male and female juvenile offenders. This study is the first to explore these interrelations in such a population.

It is important to bear in mind, when interpreting the results of this study, that this sample is drawn from a population of serious (felony-level) offenders. Accordingly, the boys and girls whom parental and partner influences may have kept out of trouble in the first place are not represented here. Because we have preselected youths with atypical offending behavior (relative to the general population), the range of the primary dependent variable (self-reported offending) is reduced, so results may not apply to broader populations, and null findings may be more likely, compared with what might be observed in a sample that includes non-offending youths.

Our observations are generally consistent with expectations based on previous studies. Girls tend to have longer relationships, fewer romantic partners, less “risky” dating behaviors, and comparatively older partners than do boys (Carver et al., 2003; Young & D'Arcy, 2005). However, girls and boys both reported similar levels of antisocial encouragement from romantic partners.

In accord with previous studies of youth (Laub, Nagin, & Sampson, 1998; Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, 2002; Sampson & Laub, 1990) we found little evidence that general partner characteristics are associated with delinquency. For example, although 23% of our female offenders were dating someone over age 20 (compared with 7% of male offenders), our results indicate that age difference is not directly related to offending. In fact, the only relationship characteristic related to self-reported offending was antisocial encouragement. So, while we did not find evidence that the presence of an older boyfriend was associated with problem behavior (as has been reported by Young & D'Arcy, 2005), we did find that the amount of antisocial encouragement a girl receives from her boyfriend is important.

The most powerful association between romantic relationships and delinquent behavior for girls involved the degree of antisocial encouragement exerted by the current romantic partner. Though it is tempting to leap to the conclusion that antisocial encouragement leads to antisocial behavior, the observed finding could indicate, instead, that antisocial girls are more likely to choose partners who condone or encourage such behavior.

Particularly noteworthy is the observed relation between the quality (warmth vs. hostility) of parental relationships and the romantic partner's level of antisocial encouragement. Although research has shown that delinquent girls tend to have more negative relationships with their mothers than do delinquent boys (Rosenthal & Doherty, 1985), our study indicates that girls who have a negative relationship with their father (characterized by low warmth and high hostility) are more likely to have boyfriends who encourage antisocial behavior. Analogously, boys who have negative relationships with their mother are more likely to have girlfriends who encourage antisocial behavior. This does not necessarily imply that boys choose girlfriends who remind them of their mothers, or that girls choose boyfriends who remind them of their fathers. While it might suggest that positive opposite-sex parent relationships protect against antisocially encouraging romantic partners, it could also indicate just the opposite: that the factors that lead offenders to choose more antisocially inclined romantic partners also lead to more troubled relationships with their opposite-sex parent.

While the above findings suggest a straightforward story (in which girls [boys] with warm relationships with their fathers [mothers] tend to have boyfriends [girlfriends] who are less likely to encourage antisocial behavior, and in which partner antisocial encouragement is related to self-reported offending), our examination of the interactions between parent relationship and antisocial encouragement as predictors of self-reported offending yielded an unexpected result. Girls with warm paternal relationships tend to have less antisocially encouraging boyfriends, yet those girls with warm paternal relationships who nevertheless do have antisocially encouraging boyfriends report the highest levels of offending. Likewise, boys with warm maternal relationships who nevertheless have antisocially encouraging girlfriends also report the highest levels of offending. This result suggests that while a lack of parental warmth may be correlated with the presence of romantic partners who encourage antisocial behavior, parental warmth nevertheless does not inoculate against these negative pressures by partners. Rather, the opposite seems to be true, with the association between partner pressure and reported behavior being strongest when parental warmth is high.

One possible explanation for this surprising observation is that, because our sample consists solely of serious offenders, it is biased heavily toward those whose parents' level of monitoring and involvement was insufficient to prevent delinquent behavior (whether prompted by peers, romantic partners, or other influences). In such a sample, it may be that those with antisocially encouraging partners who describe their parents as warm are actually interpreting permissiveness as warmth.

Taken as a whole, the results of this study suggest several key conclusions. The relation between antisocial encouragement received from romantic partners and self-reported levels of offending varies with parental relationship characteristics. Antisocial encouragement is generally the most relevant aspect of a romantic relationship in this regard, while age difference, alone, is not associated with self-reported offending. It further appears that young offenders' relationships with their opposite-sex parents are stronger correlates of involvement with antisocially encouraging partners than are their relationships with same-sex parents. Yet, among offenders with antisocially encouraging partners, those with the most positive opposite-sex parent relationships report the highest levels of offending. The present study thus underscores the importance of romantic partner pressure as a correlate of delinquent behavior among serious offenders, and highlights the need to explore, in greater detail, the relations among parental relationship quality, romantic relationship quality, and offending. Ultimately, longitudinal analyses will be required to untangle the temporal relations between these interconnected and perhaps self-reinforcing factors. The present cross-sectional analysis serves as a first step toward such future work, which may lead to an improved understanding of possible mechanisms for shaping antisocial behavior and altering the paths of criminal trajectories during adolescence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Pathways to Desistance, the study on which this research is based, is supported by grants from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the National Institute of Justice, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the William Penn Foundation, the Pennsylvania Council on Crime and Delinquency, and the Arizona Juvenile Justice Commission. We are grateful to our collaborators, Robert Brame, Laurie Chassin, Sonia Cota-Robles, Jeffrey Fagan, George Knight, Sandra Losoya, Alex Piquero, Edward Mulvey, Carol Schubert, and Laurence Steinberg for their comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript, and to the many individuals responsible for the data collection and preparation.

Footnotes

These analyses were re-run including gender in the model; i.e., gender at Step 1 and two-way interactions between gender and antisocial encouragement and parental relationship variables at Step 2, and three-way interactions among gender, antisocial encouragement, and the parental relationship variables at Step 3. The three-way interaction among gender, antisocial encouragement, and paternal warmth was significant (ν = .27, p = .01; R2 = .07 for Step 2, R2 = .11 for Step 3, p = .01). The three-way interaction among gender, antisocial encouragement, and maternal hostility was not significant.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Cauffman, University of California, Irvine.

Susan P. Farruggia, The University of Auckland

Asha Goldweber, University of California, Irvine.

REFERENCES

- Alan Guttmacher Institute . Sex and America's teenagers. Wiley; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The sounds of sex: Sex in teens' music and music videos. In: Brown JD, Steele JR, editors. Sexual teens, sexual media: Investigating media's influence on adolescent sexuality. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, Udry JR. National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Sroufe LA. Capacity for intimate relationships: A developmental construction. In: Furman W, Brown BB, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Conger R, Ge X, Elder G, Jr., Lorenz F, Simons R. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Cui M, Bryant CM, Elder GHJ. Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Zahn-Waxler C. The development of psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and future challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Windle M. Middle adolescents' dating pathways and psychosocial adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46:90–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K, Coie JD, Lynam D. Aggression and antisocial behavior in youth. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 719–788. [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C. Cognitive gender differences: A developmental perspective. Sex Roles. 1993;29:91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gowen LK, Feldman SS, Diaz R, Yisrael DS. A comparison of the sexual behaviors and attitudes of adolescent girls with older vs. similar-aged boyfriends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA. Adolescent romantic relationships and delinquency involvement. Criminology. 2005;43:177–210. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Esbensen F, Weihar A. Are there multiple paths to delinquency? Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 1991;82:83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Capaldi DM. The association of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms between partners and risk for aggression in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek L, Fine M. Family acceptance and family control as predictors of adjustment in young adolescents: Linear, curvilinear, or interactive effects. Child Development. 1994;65:1137–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub JH, Nagin DS, Sampson RJ. Trajectories of change in criminal offending: Good marriages and the desistance process. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín BV, Coyle KK, Gómez CA, Carvajal SC, Kirby DB. Older boyfriends and girlfriends increase risk of sexual initiation in young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:409–418. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus W, Branje S, Overbeek GJ. Parents and partners in crime: A six-year longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1288–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzich AC, Tarter RE, Giancola PR, Lu S, Kirisci L, Parks S. Substance use and risky sexual behavior in female adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;44:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: Follow-up at age 26 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:179–207. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex differences in antisocial behaviour: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey E, Steinberg L, Fagan J, Cauffman E, Piquero A, Chassin L, et al. Theory and research on desistance from antisocial activity among adolescent serious offenders. Journal of Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2004;2:213–236. doi: 10.1177/1541204004265864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Mental Health Association . Fact sheet: Mental health and adolescent girls in the justice system. NMHA; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moretti MM. Aggressive and antisocial girls: Research update and challenges. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2002;1:103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal PA, Doherty MB. Psychodynamics of delinquent girls' rage and violence directed toward mother. Adolescent Psychiatry. 1985;12:281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime and deviance over the life course: The salience of adult social bonds. American Sociological Review. 1990;55:609–627. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams R, Diamond L. Sex. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Wiley; New York: 2004. pp. 189–231. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert C, Mulvey E, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Losoya S, Hecker T, et al. Operational lessons from the pathways to desistance project. Journal of Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2004;2:237–255. doi: 10.1177/1541204004265875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H. Juvenile arrests 2002. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sonenstein FL, Ku L, Lindberg LD, Turner CF, Pleck JH. Changes in sexual behavior and condom use among teenaged males: 1988 to 1995. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:956–959. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Blatt-Eisengart I, Cauffman E. Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful homes: A replication in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, D'Arcy H. Older boyfriends of adolescent girls: The cause or a sign of the problem? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:410–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Siebenbruner J, Collins WA. Diverse aspects of dating: Associations with psychosocial functioning from early to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. Special Issue on Adolescent Romance: From Experiences to Relationships. 2001;24:313–336. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]