Abstract

While the consequences of aggression and violence in family settings have been extensively documented, the intergenerational processes by which such behaviors are modeled, learned, and practiced have not been firmly established. This research was derived from a larger ethnographic study of crack sellers and their family systems and provides a case study of one kin network in Harlem where many adults were actively involved in alcohol and hard drug use and sales. “Illuminating episodes” suggest the various processes by which aggression and violence were directly modeled by adults and observed and learned by children.

Aggression and violent behavior were entrenched in the Jones and Smith family, as was drug consumption and sales. Adults often fought over drugs or money and feuded while under the influence of crack and alcohol. They used aggression and violence against family members as retribution or punishment for previous aggressive and violent acts. Aggressive language and excessive profanity were routine adult behaviors and a major means of communication; jokes and insults led to arguments, often followed by fights. Most adults who were abused physically or sexually as children did the same to their own as when one mother was knifed by her daughter. Children rarely obtained special attention and support and had almost no opportunity to learn nonaggressive patterns. Rather, youths learned to model adult behaviors, such that the intergenerational transmission of aggression and violence was well established in this kin network.

PURPOSE

This paper suggests several processes by which violence and aggression regularly occur within African-American inner-city families where several substance-abusing/crack-selling adults reside. We examine how aggression and violence may be learned and transmitted inter- and intragenerationally by describing how members of various generations interact with each other within a specific family/kin network. In so doing, we expect to gain some understanding of the blatant and subtle ways in which violence is modeled or practiced by adults and internalized by children and youths in the household.

While this paper reports a case study of a particular family/kin system—the Jones and Smith family1—the manifestation and transmission of aggression and violence are common behavioral patterns that permeate many other substance-abusing households. Children born into or raised in such households routinely learn aggressive and violent behaviors through observation and interaction with their parents and other kin. Indeed, such youth have few, if any, opportunities to learn nonviolent or nonaggressive behavior patterns.

This paper intends to show how children raised in households or family settings where drug-abusing adults are present are often deprived of the opportunity to learn conventional behaviors that prepare them for life in conventional society. This sets up a self-perpetuating situation. Adults who participate in conventional life and have gained decent education and employment are few and far between, and are often unavailable as mentors and resources for children. In the meantime, children learn destructive and abusive behaviors during the limited interaction that they have with nonconventional adults. This is consistent with other studies which have demonstrated how violence and drug abuse may be transmitted across generations from parents to offspring (Widom, 1990; Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; Gabarino & Platz, 1986).

In addition to gaining some understanding of the social processes that underlie the inter- and intragenerational transmission of drugs and violence, a second issue informs this paper: namely, why drug addiction and violence—once they take hold in a population—are so difficult to root out. Why are nonconventional behaviors (e.g., aggression and violence) entrenched within a certain population segment? While economic, historical, and cultural forces play a role in this entrenchment (see Lemann,, 1991; Butterfield, 1995), the focus of this paper is on the extent to which the interpersonal transmission of aggressive and violent behaviors operate at the microlevel, within the larger social context.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Theories of Family Violence

Family violence is a special case of violence with its own body of theory (Gelles, 1987). Gelles and Strauss (1979) identified unique characteristics of the family as a social group which contributed to making the family a violent-prone interaction setting. Upon closer examination, Straus and Hotaling (1980) noted that certain characteristics may serve to make the family violence-prone or conflict-prone, but these may be the same characteristics that also have the potential for making the family a warm, supportive, and intimate environment.2 This double-edged phenomenon often occurs when family members know and understand each other almost too well. The main factor, though, that may make the family conflict-prone is its existence within a cultural or subcultural context where violence is tolerated and accepted—and even mandated in some situations (See Lewis, 1966).

Moreover, it has been well-documented that the African-American family structure, with its linkages to extended family and kin, has given blacks the ability and flexibility to adapt to changing conditions from the time of slavery through the present. (See Herskovits, 1941 [1990]; Stack, 1974; Aschenbrenner, 1975). Accordingly, this same extended family structure, which is a traditional strength among African-Americans, may facilitate the transmission of aggression and violence from one generation to the next, because it brings a considerable number of individuals from different generations into interpersonal contact with one another.

Social learning theory (Bandura, Ross & Ross, 1961; Bandura, 1973) suggests that the intergenerational transmission of family violence results from considerable experience with and exposure to aggression and violence as a child or adolescent. Regular experience with episodic and repeated acts of aggression and violence provides children and adolescents with learning experiences that are difficult to alter. Through observation of adult behavior, children informally learn which people may be appropriate victims for family violence, when family violence is appropriate, and how to justify acts of family violence (Gelles & Straus, 1979).

Modeling is a form of social referencing (Campos & Steinberg, 1981) which helps children evaluate the safety and consequences of their own actions; it provides new meanings to an assortment of environmental episodes (Schreiber, 1992). Children observe aggression, imitate others in the family, and learn to survive by adopting aggressive and violent behaviors.3 They witness how violence is often used as a form of punishment or retaliation (Wolfgang & Weiner, 1981) and how beliefs about right and wrong and assignment of blame are used to excuse or justify aggressive behavior (Felson & Tedeschi, 1993). When violence and aggression are common features of family life, children conclude that aggression and violence are expected and acceptable behaviors (Straus, Gelles, Steinmetz, 1980; Bandura, 1973; Feshback, 1980)—which are not only normal but inevitable, desirable, and good (Staub, 1996).

The thesis of this paper, then, stems mainly from this body of research. We expect that modeling—which is conveyed by what adults say, but even more by what they do—has a major role in the transmission of violence and aggression both inter- and intra-generationally. Moreover, we anticipate that after violent and aggressive behaviors are modeled, the situation is intensified when hostile behaviors are evoked in return (Dodge & Frame, 1982; Staub & Feinberg, 1980). Exchange theory suggests that individuals use violence toward family members if they have learned that this is an appropriate and normative means of dealing with other people and if the costs of being violent are lower than the rewards. Even when the costs of involvement in violence in some families are high (e.g., being hit back, being arrested and/or imprisoned, and/or losing social status), these costs are rarely sufficient to deter or prevent violent behavior by those who have learned and practiced violence from an early age (See Goode, 1971).

Substance Abuse and Family Violence

The illegality of some drugs (especially heroin, cocaine, and crack) and the development of illegal drug markets and subcultures of drug use and abuse brings another important dimension to the issue of violence in family life. A wealth of information supports the notion that substance abuse is related to violence in general and family violence in particular. Substantial associations have been found between alcohol use and family violence and abuse (Gelles, 1987; Straus, Gelles & Steinmetz, 1980; Wolfgang & Weiner, 1981). Likewise strong associations are shown between the use, and especially the illegal sale, of heroin, cocaine, and crack with high levels of violence in both community and family settings (Goldstein, 1985; Goldstein et al., 1988; Fagan, 1994a, 1994b; Fagan & Chin, 1990). Persons who routinely engage in illegal sales of heroin, cocaine, and crack are disproportionately recruited from among those who are most violent. Most sellers were raised in household/family systems that were plagued by violence, and these people currently reside in violent households as well. Moreover, the interactions among sellers further increase levels of violence (Johnson, Golub & Fagan, 1995), especially when aggression and hostility move with them from the street and into their households—and toward other family members.

Previous research has documented changes in the drug subculture with the advent of crack (Dunlap, 1991, 1992, 1995; Bourgois & Dunlap, 1993; Inciardi, Lockwood & Pottieger, 1993). Many crack-abusing parents were unable to provide a residence for themselves and their children. This inability to provide housing was a critical element distinguishing crack users from earlier generations of drug abusers (Dunlap, 1992). In addition, when crack was involved, violence and abuse were an intricate part of all key relationships, both male/female and parent/child. A principal reason for violence was that many economic resources and much income, often earned from illegal activities, were disproportionately expended on drugs. Very little money, if any, was left for expenditures to support family and household responsibilities. Drugs come first; other responsibilities come later—if they are thought about at all.

Clearly, in substance-abusing families, the adults’ preoccupation with the acquisition and consumption of drugs and alcohol leaves them little time to attend to, address, and incorporate the needs and interests of children into their activities. The socialization of children is further influenced by the routine threat and reality of violence (Dunlap, 1991, 1995). Parents and other kin bring these violent and aggressive behavioral patterns into their relationships with children, such that the children at an early age learned violent and aggressive behaviors that may enable them to survive in these households and on the streets of the inner-city. These adults, at the same time, failed to teach children conventional behaviors, because they were either unwilling to do so or incapable of setting a good example (Johnson, Dunlap & Maher, in press). Children therefore have little or no opportunity or exposure to the cultural values, behavioral patterns, and skills necessary for conventional roles, which would enable them to function in the larger society—that is, in social circles where drug abuse was not a critical activity and where expectations of nonviolence existed.

METHODOLOGY

The data emerge from an in-depth ethnographic/ethnomethodological study of the Jones and Smith family, collected during two larger, on-going projects funded by the National Institutes for Drug Abuse (NIDA). The Natural History of Crack Distribution/Abuse project collects ethnographic data on the structure, functioning, and economics of cocaine and crack distribution in New York City by gaining access to crack sellers and distributors (Dunlap, Johnson, Sanabria, Holliday, Lipsey, Barnett, Hopkins, Sobel, Randolf & Chin, 1990; Williams, Dunlap, Johnson & Hamid, 1992; Fagan, 1992) and to their households and family life (Dunlap & Johnson, 1994). Since 1989, ethnographers have developed close relations with numerous crack sellers and, in some cases, their families. In 1992, the senior author began to focus on the interaction patterns within households.

Dealers and family members, both male and female, were recruited, and one-on-one in-depth interviews were conducted. For many subjects, the in-depth interview was clearly the only time in their lives when they had talked fully and openly about their personal histories, drug-dealing behaviors, hopes, dreams, problems, and crises. Close relations and rapport were established and maintained with many of the dealers and their families over a period of three years. Males have been overrepresented in this study simply because men dominated drug distribution.

The Violence in Crack User/Seller Households: An Ethnography was specifically designed to examine the intergenerational processes of the transmission of violence. Over fifteen families and their households have been interviewed and their behavior patterns observed. The volume of data collected so far for these studies is one of the richest in this field: thousands of pages of transcribed recorded material and fieldnotes have been compiled which can be analyzed with powerful, new hypertext programs (Manwar, Dunlap & Johnson, 1994).

Even more essential for this paper, however, were direct ethnographic observations conducted in the households of the Jones and Smith families. Rarely did studies examine the family and kin context in which aggression or violence took place or the cultural context within which such families function, and few studies have demonstrated how the unique background and experiences of family and kin might influence the dynamics of family violence. In this research, however, the intensive study of one kin network can tell us not only about their family life, but also can point up distinctions between these families—engaged in drugs and violence—and others with more conventional behaviors.

The ethnographer thus had to establish some deep personal ties in order to collect intimate data: she observed and recorded what people did (or did not do) towards each other, how they spoke to each other, what they said (or did not say) to each other, and how they expressed themselves through actions and body language. Interaction patterns at family/kin gatherings and during illnesses and other times of crisis were also recorded and studied. All of these things were critically important for understanding the processes related to violence and aggression.

Through the use of observations, interviews, and fieldnotes, this research has provided an in-depth look at the interaction processes by which aggression and violence in family life were modeled and learned. What it was like growing up in a household with adults who abuse and sell drugs? Detailed aspects of these people’s lives and their complex interaction patterns could not have been adequately measured through a solely quantitative approach—not even by their self-reported behaviors during an interview.

A key focus of this paper will be upon illuminating episodes, which may be considered to be “social snapshots in time.” Direct ethnographic observations of interactions among two or more persons provided flashes of understanding about several major social processes associated with the intergenerational transmission of aggression and violence which have not yet been well understood or documented.

Thus, this rich ethnographic material contained numerous illuminating episodes which revealed how several social processes were involved in the intergenerational transmission of aggression and violence and how the drug and violence subcultures affected one particular family/kin network, the Jones and Smith extended family. After an introduction to some of the people in this kin network, this paper was organized with respect to the sites within which violent and aggressive behaviors and abuse take place. These occur with respect to: (a) child rearing, (b) sexual relationships, (c) consumption of drugs, money, and economic resources, (d) routine verbal interaction, and (e) nonroutine events, such as wakes and funerals.

It should be noted, however, that the current research is exploratory and fundamentally inductive. The illuminating episodes can provide the reader with many important leads and hypotheses about how to study larger social processes which may be involved in child abuse and neglect, sexual abuse, and partner violence, but they do not define or flesh out the more subtle, abstract, and long-term socialization processes of the persons who are depicted—in much the same way that a snapshot does not explain much about the lives of the persons over time. The exact mechanism by which these social processes operate was left to interpretation, although the data analysis can suggest directions for future work in this important area.

THE JONES AND SMITH FAMILY/KIN NETWORK

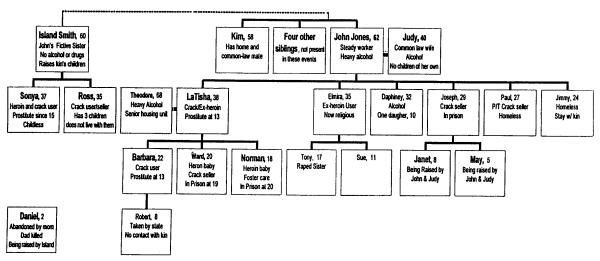

The Jones and Smith families may not be representative of most inner-city minority families or even those families with substance-abusing members. But these families are not dramatically different than many other inner-city families with one or more drug-using or drug-selling adults (Dunlap, 1992, 1995; Dunlap & Johnson, 1992). Rather, this family/kin system provided us with a genealogy, and therefore a conceptual apparatus, by which to begin documenting the intergenerational processes associated with aggression and violence (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Jones and Smith Kin Network

Most of the family and kin network had a long and intricate history of substance abuse. John Jones (age 67, in 1995) and Island Smith (age 63) were brother and sister.4 Island had two children. Her son, Ross, was a freelance crack seller who was dying of AIDS at age 38. Island’s daughter, Sonya, was a ex-heroin user, now a crack-abusing prostitute at age 40 (Dunlap & Johnson, 1992; Dunlap, 1995; Johnson, Dunlap & Maher, in press). While Sonya had no children, Island was extensively involved in raising several children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of her siblings. Island was the only person in the kin network who did not indulge heavily in either drugs or alcohol.

John Jones had full-time employment as a school cook; he is the only person in the kin system to have steady legal employment. John had six children from three different relations. When talking about growing up in Harlem, John joked that he was a “bad little boy” who was “expelled from school at five years old.” While likely an embellishment, this claim suggests the extent to which being a “bad ass” was valorized and reflects John’s self-image within the family context. Both John and his first wife Lillian were heavy alcohol consumers, and John remained so at the time of this study. By this time (1989-1994), John lived with his common law wife Judy (age 44), who also indulged heavily in alcohol. His first three children, LaTisha, Elmira, and Daphiney were by Lillian, who died when the children were very young. The eldest daughter, LaTisha, was a crack prostitute during the study period. Elmira was an ex-heroin user who had renounced street life in favor of religion and confined her interactions with the family to times of crisis. Daphiney, the youngest daughter, was a heavy alcohol consumer who occasionally smoked marijuana. John’s other three children, Joseph, Paul, and Jimmy, are from two different relations. In 1990, Joseph was in prison for selling crack. Two of Joseph’s children, May and Janet (John’s grandchildren), lived with John and Judy. Paul was a part-time drug seller and unemployed. Jimmy used drugs on and off, was unemployed and homeless, and continued to move between family members during the study period.

CHILD REARING

Psychological and Emotional Neglect of Children

The home environment was a critical element in the transmission of violence and aggression intergenerationally. Children who grew up in households where a large portion of monetary resources were spent on drugs and alcohol often experienced poor family relationships and rarely received any expressions of physical closeness, kindness, and affection. Often parents or caregivers were too deeply immersed in the drug subculture to pay attention to children (Egeland & Scoufe, 1981; Emde 1985).

Children were generally ignored and left unattended much of the time. Toddlers were left to crawl around on a dirty floor which contained many dangerous objects, so often they injured themselves. Children were left to watch television or entertain themselves. Adults did not expect to pay attention to their children and consistently demonstrated a lack of awareness that children had special emotional and psychological needs. Parents, relatives, and caregivers did not spend any time trying to assess a child’s feelings or emotional state at any given moment. Harsh and crude interactions confronted children, with emotional neglect starting at an early age and continuing throughout childhood.

In the Jones family, cuddling and other forms of demonstrative affection took place, but often adult attention alternated rapidly between cuddling and whipping. An episode of this type of adult-child interaction occurred as the Jones family gathered on the eve of LaTisha’s death (See more below). Quoting from fieldnotes:

Family members came to the apartment of John’s sister, Kim. John’s two grandchildren, May (age five) and Janet (age eight), were present. During the early part of the evening, adults were attentive to and played with the children. As the evening drew on and adults indulged in their alcohol/drug of choice, the adults became tired of the children. The eight-year old, Janet, knew to leave the adults alone. She pulled back and only interacted with them when adults initiated contact with her. The youngest one, May, had not learned this lesson yet. She continued to run about and attempted to engage adults even though the adults had turned their attention to one another. Eventually May was given a whipping, for which she cried too long, was subsequently given another whipping, and placed in the bedroom with the lights out.

It is clear from this example that the child’s desire to share feelings and communicate with adults or parents was sometimes destructive emotionally, and physically involved spanking and hitting (“whipping”).

Very seldom did the children in this family receive the support of parents and care-givers; they were rarely encouraged and accepted just for being who they are. The “comfort zone” (Biringen & Robinson, 1991) that children learned in such households was to stay out of the reach of adults in order to reduce the risk of exposure to adult abuse and violence. Children quickly learned to watch adults to determine when it was safe to interact with them and when it was not. Janet had learned this lesson by eight years of age. May was being taught this lesson with the whipping she received. Children thus began to limit their interaction with adults and caregivers and were not encouraged to explore and expand their boundaries of interpersonal interaction. The ensuing limitations on the nature and degree of interaction with adults may stunt the child’s psychological development and were critical in constructing and reshaping children’s psychological functioning and behavior (Schreiber, 1992; Frodi & Smetana, 1984).

May and Janet’s father, Joseph, was in prison for selling crack. Their mother had gone South to kick her crack habit, met another man, and was attempting to start a new life for herself. The grandfather (John) and his current girlfriend (Judy) reluctantly agreed to rear the two girls. But these children were not free to display a broad range of expressions. Although they were given attention, the whims of the grandparents and other family/kin dictated the timing. When adults became tired of dealing with them, the children learned—in an abusive and abrupt manner—that adults were not to be interacted with. Failure by children to abide by such unclear adult rules resulted in physical punishment.

Children were expected to respond passively to what was meted out. They were expected not to fight their parents, even in the face of violence or threats against themselves. Children were also punished for disobeying foolish, trivial, or inappropriate commands by adults. The following fieldnote demonstrates what children must endure:

She [Island] related that Sonya beats Daniel [age two] because he runs and jumps and plays. Sonya does not want him to get toys to play with, She wants him to keep quiet and be still. Island says that Sonya treats him like he is in a jail house, that she tells Sonya that he is not in prison not to treat him like he is in jail. When Daniel asks Sonya for a ball she is mean to him, tells him to shut up that he doesn’t need a damn ball. She is meanest to him when she is high; the higher she gets, the meaner she gets.

There were many instances when a parent or adult may buy a toy (e.g., a ball) and then demanded that the child not play with the toy. Such commands are generally issued using aggressive language. If children disobeyed and played with the ball, they were punished for not obeying the commands. The discipline might involve more violence and aggression.

Such punishments, however, would be one of the rare occasions in which the child directly related to the adult, by obtaining his or her direct attention. Thus, children learned that by disobeying adults, they would receive attention which was otherwise withheld. Thus, disobeying adults or authority figures was reinforced as an appropriate behavior by which to gain adult attention.

Child Abuse—Physical and Sexual

Persons growing up in families such as the Jones or Smith family were often likely to have been physically, sexually, and emotionally abused. Many studies record frequent incidents of sexual abuse and physical abuse among women substance abusers (Wood & Duffy, 1966; Singer, Petchers & Hussey, 1989; Dembo et al., 1987; Downs, Miller & Gondoli, 1987; Finkelhor, 1979). Much emotional rage from childhood was acted out in aggressive and violent ways by young adults in substance-abusing households. Their intractability can be seen as a response to the pain that they suffered.

LaTisha’s son, Norman, illustrated the degree of sexual and physical abuse to which some children were subject. As a child, Norman was subjected to extremely damaging punishments. LaTisha punished him many times by abusing his sexual organs, such as pulling back his foreskin. By the time Norman was six years old, he was frequently involved in fights at school and had begun to run away from home. At age seven, he attempted to stab someone and was placed in a psychiatric ward. At eight, Norman, who was born with heroin in his system, was being given hydrothorazine. His behavior can be seen as the outward manifestation of his continued sexual and physical abuse. A caseworker who had worked with Norman since childhood substantiated the abusive and neglectful treatment he received from his mother:

I met [Norman] in 1979… He was eight and he was there on a placement, because he was found wandering around in the Bronx, after having been beaten by his mother… The court had decided he had to be in a sheltered situation away from his mother. Then his mother never visited him. From there, he went to a place called The National Villa. And he was in a residential treatment center up by 118th Street and Phyllis Avenue.

Norman’s case is indicative of the kinds of poor family relationships that often include physical and sexual abuse. Discipline was either nonexistent, lax, too strict, or clearly abusive. Love, affection, and appropriate emotional responsiveness were effectively absent. In Norman’s case, disciplinary practices also constituted sexual abuse. When Norman aged out of foster care at age nineteen, he was homeless and was committing robberies and selling drugs. By the mid-1990s, he was already serving a long prison sentence (also see Butterfield, 1995).

Deviant Role Models

The process of learning aggression and violence began at a very early age in Island’s household, as parents and other relatives provided deviant role models for their children in the context of their drug and alcohol consumption. Excerpts from fieldnotes taken at Sonya’s 40th birthday party demonstrate how two-year-old Daniel was being socialized into the drug subculture:

During this time most of the people have gone into the hall again. Daniel is in the middle of the floor shooting red dice. He is doing this with another female (who looks like a crack user). She is playing with him and he is showing off that he knows how to shoot dice. Ross comes in and makes them stop. He fusses at the woman for shooting dice with Daniel and she leaves. I ask Ross why he fuss at the woman, I say “You know Daniel is always showing people he knows how to shoot dice.” Ross relates, “Yea but he don’t need to be shooting it with her.”

…[Island] also said, “when Mick [an unrelated adult living in Island’s house] be high and nodding on the couch, Daniel see him nod and say, ‘Mick fucked up, mama, Mick fucked up!’” She laughed at this and I laughed also. I said (while laughing), “Well, sounds like Daniel is a bad little guy already.” This seems to make everyone feel good. Perhaps they feel that he will survive if he cultivates particular behaviors. Island related that Daniel run with Ross [the crack seller] and them [his associates who are crack users and sellers] out in the hall and he tries to do like they do.

In this household, Ross was Daniel’s father-figure. He provided child care while conducting his drug selling business. Daniel was learning and imitating the behaviors of that subculture. Already Daniel had learned gambling—by shooting dice—a favorite pasttime of many sellers. He was also learning how to interact with drug users. When Ross made the woman stop shooting dice with Daniel, his concern was with her setting a bad example. Daniel thus learned how to treat specific people, in this case, a crack-using female.

Significantly, Daniel has a very limited vocabulary at age two. Among the first words Daniel learned was “fucked up” to describe someone who was high on drugs. At an early age, Daniel had learned how to use adult curse words, be aggressive and threatening towards others, and behave as a “bad ass.” Moreover, by interacting with and observing adults (especially Ross), Daniel was internalizing key values and patterns of the drug subculture. He had no other conventional adults to learn from and limited exposure to other children his own age.

Another illustration is LaTisha and her daughter Barbara. Although LaTisha’s father John gave much rhetorical emphasis to the value of education, she received almost no support or encouragement to stay in school or do well. There was no help with homework or parental participation in school activities.

In the same way that LaTisha recalled the impact of her father’s heavy alcohol consumption on her own childhood, Barbara reconstruced home life in the shadow of her parent’s heroin use. Barbara remembered seeing her parents “shoot-up” and examining their “works” when they were not at home. Recalling the effects of heroin on her parents, Barbara hated the way drugs affected their appearance: they looked “very ugly,” and “did not look nice.” Nevertheless, by ten years old, Barbara was indulging in cigarettes and alcohol. Her teenage years saw marijuana, angel dust, cocaine, and finally, crack added to her consumption repertoire. Although Barbara made a conscious choice to avoid heroin, she had been socialized into illicit drug use behaviors at an early age. Her mother and other family members modeled heavy involvement in drugs and alcohol and in the illegal sale of drugs. Barbara was also sexually and physically abused, and at thirteen years old she was already exchanging sex for money and learning the trade from her own mother. She became a high school dropout and had a son at age fourteen by a thirty-five-year-old customer.5 Like her mother, Barbara was not provided with the encouragement or the necessary resources to enable her to stay in or complete high school. Rather, LaTisha provided Barbara with an effective model for drug consumption and prostitution.

SEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS

Sexual Abuse Among Men and Women

Virtually every female in the Jones and Smith family related episodes of forced sex well before age sixteen and often with an adult man. Males often reported early forced sex in this kin network also. The expectation of early onset of sexual experience was often evinced in language, for example, when one male family member in the Jones/Smith kin network commented that Janet, at age eight, was going to grow up to be “one fine bitch.”6 These and other observations by adult males often reflect their sexual interest in a prepubescent girl and may result in early intercourse if the man was left alone with her.

Another form of sexual abuse took place when deviant acts were minimized or hidden by the family. One example occurred when Elmira’s son Tony raped her daughter, Sue. Elmira did not know what to do. She did not want to turn her son over to the police and bring charges against him, but she could not let him stay in the house with Sue any longer. Seeking a safe place for Tony until she could straighten things out, Elmira asked her sister LaTisha for help. At the time, LaTisha (age 38) was living with an older man, Theodore (age 68), in an apartment in a senior citizens building (Also see Hamid, 1992; Maher, Dunlap & Johnson, 1996). Elmira convinced LaTisha to let Tony stay with her and Theodore. Theodore did not want Tony to stay, but LaTisha insisted. Tony’s presence and that of his male friends created additional stress in LaTisha and Theodore’s relationship. After a few weeks, Theodore wanted Tony out of the apartment and asked LaTisha to do something about the situation. LaTisha told Elmira—who became angry because she did not have enough time to find Tony somewhere else to live.7

In this incident, aggression and violence which started in one family member’s household was transferred to the household of another family member. But perhaps more importantly, this illustrated the perpetuation of sexual abuse and exploitation. Both Tony and Sue clearly needed professional help, and the family was making matters worse through their inaction and reliance on a “geographic cure.” By its failure to take appropriate action, the family often permitted the abuse to go unresolved and unpunished, which may also lead to further abuse.

Sex Work

Within this family/kin system, a reasonably accurate prediction of almost any girl’s future occupation would include prostitution. LaTisha, for example, began to exchange sex for money in junior high school and dropped out of school at sixteen to have her first child Barbara. After Barbara was born, LaTisha made small attempts to return to school but eventually began to hang out in the street and “party.” LaTisha eventually became a heroin addict in the 1960s, and subsequently became a crack abuser in the mid-1980s.

Although violence and abuse were significant features of LaTisha’s relationship with her children while she was using heroin, her use of crack was coterminous with a subsequent escalation in abusive family relationships. The crack and violence relationship was most graphically illustrated by mother and daughter prostituting together for crack.

LaTisha taught her daughter how to be a prostitute. Although she may not have done so intentionally, she, in effect, became Barbara’s teacher and mentor in her role as an older, more experienced prostitute. LaTisha taught Barbara how to defend herself, when and how to use violence, how to take abuse, how to rip off tricks, and how to survive on the streets, in addition to sexual techniques, such as intercourse and oral sex. In 1989, Barbara and LaTisha were prostituting at the same park in the study site. Often they ripped off customers together, pooled their money to buy drugs, and shared drugs and money with each other. They smoked crack together, sold their bodies together, and fought with each other. They routinely engaged in loud verbal arguments over customers, money, and drugs.

The use of crack not only contributed to LaTisha’s and Barbara’s aggression and violence among themselves, but both understood that the life of a prostitute exposed them to violence by customers, pimps, and drug dealers. According to fieldnotes:

…LaTisha begins to talk about young women and how they give blow jobs for a dollar… in hallways or anywhere… [T]his is the reason a lot of violence takes place; the young women take chances which open them up to violence.

The violence committed by men against female drug users was frequently in the context of intimate relationships (Maher & Curtis, 1992; Maher, 1995) as well as on the street (Bourgois & Dunlap, 1993; Reed, 1981; Mondanaro, 1989; Stevens et al., 1989; Vandor, Julian & Leone, 1991).

Drugs and Violence within Relationships

The ability of men and women to relate to each other respectfully was further undermined when drugs became a central element of the relationship (Rosenbaum, 1981; Spunt et al., 1990; Goldstein et al., 1988). In short, the potential for violence was compounded in all situations where one or both parties used drugs.

Barbara’s relationship with her boyfriend Howard illustrates the potential for violence in male-female relationships and how this violence may be acted out in the next generation. When her mother died, Barbara did not have anything to wear to the funeral. Her new boyfriend bought her a dress and a pair of shoes. Howard tried to stay with her and comfort her. But Barbara was extremely aggressive and violent in her language and actions toward him. At the wake, while walking down the street, and later during the family gathering after the funeral, Barbara used aggressive language and behavior towards him, as demonstrated in the following fieldnote:

Barbara curses out her boyfriend. She tells him he left her last night at the party. She tells him to “get the fuck out of [her] life… carry your ass motherfucker!” She talks as mean and as nasty to him as she possibly can. He accepts this verbal abuse. He does not say anything. When a slow record come on they hug, kiss, and dance with each other. Off and on she curses and ridicules him. She called him “mother-fucker” in several different ways. She asks him why was he hanging around. She then relates to him that he knows she had some “good pussy” and how she could make his “dick cry.”

What Barbara has learned about sex was evident. Her inability to accept comfort and aid was especially evident. Her boyfriend attempted to provide kindness and compassion. Aware that Barbara’s mother had just passed away, that the family was rejecting her, and that she needed someone for emotional support, Howard bought Barbara clothes to wear and tried to console her in her grief. But Barbara responded to his efforts in the only way that she knew. She had grown up in a cold and hostile parent/child relationship and was prepared for a cold and hostile world. Her relations with family and kin trained her to be aggressive, violent, and abusive in her dealings with others. When someone attempted to relate to her in a manner suggestive of unconditional love and respect, she was unable to accept it. Given the continued absence of kindness and compassion in her life, Barbara brought her relationship with Howard into a realm with which she was familiar. Both Barbara and LaTisha were unable to relate emotionally and affectively to significant males. Relationships with men were, for the most part, defined by their sexual content and calculations of material advantage and access to drugs.

CONSUMPTION OF DRUGS, MONEY, AND ECONOMIC RESOURCES

Much of the violence and aggression occurred when marginal resources, especially cash, were often expended on drugs. While love was oftentimes shown by sharing drugs or alcohol, at the same time, a couple might have frequent fights over money and everything else associated with them.

LaTisha’s relationship with Theodore illustrated some of the economic problems faced by drug-using men and women (Also see Hamid, 1992). Theodore provided her with a place to stay and his social security check as a source of income.8 LaTisha systematically conned him, so that she and her family could take advantage of the situation. Among other things, LaTisha stole his food and money, so that she and Barbara could purchase crack.

The violence inherent in their relationship exploded into a crisis. During a crack binge, Barbara turned up at Theodore’s apartment and demanded money from LaTisha. LaTisha replied that she did not have any money. Barbara then demanded that she get it from Theodore. When LaTisha related that he did not have money either, Barbara responded in the way she knew, that is, becoming verbally aggressive and threatening. Their argument quickly escalated into a fight between the two women. When Theodore attempted to intervene, Barbara produced a knife and was physically violent towards Theodore and LaTisha. First she stabbed Theodore in the legs; then she cut LaTisha, and left. Both Theodore and LaTisha were hospitalized.

Although the fight with Barbara may have contributed to her condition, LaTisha’s poor health was largely attributable to years of drug and alcohol abuse. After being hospitalized for a few weeks, LaTisha died. (The medical cause of death was not provided to the family.)

Generally the estate of the deceased person was accessed and distributed among family members. LaTisha had few possessions. Theodore told Island at the hospital that she could have LaTisha’s coat and some clothes that she kept at his apartment. Barbara received the few meager possessions LaTisha had when she entered the hospital.

Drug and alcohol consumption not only depleted LaTisha economic resources, but placed a severe strain on family members emotionally and instrumentally. She was abusive and neglectful to her children and could not provide for them. Her children were later taken and raised by her relatives and the foster care system. LaTisha’s violence and aggression was learned by her children, eventually leading to the final fight between mother and daughter, and to LaTisha’s hospitalization and subsequent death.

ROUTINE VERBAL INTERACTION

Verbal Aggression and Profane Language

Among the Jones and Smith kin, aggressive and profane language was part of everyday vocabulary. Adults used aggressive language as a way to impress themselves with their importance in the world and as an attempt to dominate others. Their normal everyday vocabulary included profanity, reflecting the way they thought. Profanity was a fundamental and normative part of their personality and socialization: it was not merely used for emphasis.

For example, as the Jones family gathered for LaTisha’s wake, the implication was that everyone had to buy his/her own choice of substance. John went to the liquor store and brought back a bottle of vodka. Kim and her boyfriend were offended. They did not drink vodka; they knew that John knew this. In a kidding way, Kim said to John, “Motherfucker, you know we don’t drink that shit.” She then sent her boyfriend out to buy their brand of alcohol. Later in the evening, while serving food to everyone, Kim commented that she was giving out food when no one was giving anything in return.

Both the form and content of verbal interaction were important elements in the modeling process. Children witnessed how adults communicate with one another and patterned themselves after them. In conventional society, adult-child communication is structured differently from that used exclusively among adults. This was not the case within the Jones and Smith family, where little distinction existed between the form and content of verbal interactions among adults as compared with adult interactions with their children, as the following fieldnote demonstrates:

…(Sonya) offers some [food] to Daniel and he drops some of it on the floor and attempts to pick it up and eat it. It had fallen in a puddle of water that was dog urine by the couch. Sonya took it out of his hand and said to him it had fallen in “piss” and not to eat it. Something like “don’t eat that shit out of the piss. Ma! he took that out of the piss.” Sonya walked back into the bedroom and Island continued to feed Daniel from the food from the bag.

Jokes and Put-Downs

Aggressive language was also used both as humor and as a put down. Speakers often flip-flopped between the two. Many statements had a double edge, such that both children and adults would be uncertain whether the speaker was joking or serious. A joke or comment could be easily taken the wrong way by the listener. Frequently, a joke was heard as an insult; this often escalated into an argument entailing more cursing, verbal aggression, and the potential for physical violence. Arguments often began with small jibes at the person that initially appeared trivial and unimportant in terms of the content being discussed; these may or may not be responded to immediately. When the person to whom the insult was directed inevitably got upset, however, the speaker proclaimed to be only joking, but an argument might ensue regardless, sometimes leading to fights among the parties. According to fieldnotes:

At the wake, Kim remarked that Judy was feeding the children “left over food” and riding around most of the day with hungry children in the car. She continued to joke about Judy and the apparent deficiencies with her cooking. The joking escalated, providing a thin veneer for Kim’s grievances about how Judy cared for May and Janet, and in particular, for not feeding them properly. As the joking escalated, family members took sides. The joke/argument began to dominate the conversation; some family members made “off the wall” remarks and others talked seriously and with extensive profanity. In frustration, Judy retaliated, “I will bring them to you bitch every day; then you can feed them, shit.” Kim then drew the children into the joke/argument, claiming, “they [the children] will be glad to come to my house to eat—seeing that they don’t get shit anywhere else.” Eight-year old Janet became uncomfortable, as if she had been involved in many similar scenes. She was clearly apprehensive about the outcome. Kim wanted Janet to agree that she liked Kim’s food better than Judy’s. Kim also wanted Janet to imply that she was hungry much of the time. Janet was placed in the middle of an argument between adults that began as a joke. The expression of fear and uncertainty on Janet’s face suggested she did not know with which adult to agree. Judy was smiling and still somewhat “joking,” but Kim’s expression had changed; her expression was somber and angry.

Janet was sitting in a chair behind the table where she had been given a plate of food and told to sit down and eat. She alternated eating the food with a fork and her fingers. She was picking at the food. Most of the time she was looking into the plate, but listening very carefully at what was being said by the adults. When Kim remarked about Janet liking her food better than Judy, Janet became fearful. She stood up but kept eating her food and looking in her plate. Her body was rigid as she listened to the adults argue and joke.

The key element as to whether the scenario might become violent was when such jokes, jibes, and arguments were really veiled attempts to dominate the other person. Family members were particularly well-acquainted with and insightful about the weaknesses and sensitivities of one another. In fact, the pattern that emerged was that when these jokes led to aggressive arguments and then to fights, it was frequently the perceived “loser” of the verbal contest who threw the first punch, because he or she felt disrespected (“dissed”) or put down.

Parents, kin, and other adults rarely communicated with children in a manner calculated to teach or demonstrate age-appropriate conventional behaviors. Rather, the process by which jokes become arguments sent children confused messages and drew them into adult conflicts. Children consequently were forced to watch what happened and had to “pay attention” (Johnson, Dunlap & Maher, in press). As with Judy and Kim, jokes and arguments between adults often reflected unresolved anger resulting from previous arguments and ongoing family conflicts. When these conflicts inevitably resurfaced as jokes, adversaries systematically attempted to gain allies and support for their position by co-opting or drawing others into their conflict. Such perceived allies were adults or children like Janet.

These arguments, which frequently occurred in front of children, were integrated into everyday patterns of familial interaction. The children learned not only the language content, but also how to provide compliments with a twist, small jab, or small insult. Children were likewise taught the spoken and unspoken norms associated with aggression and violence in conflict situations. They learned that verbal aggression, in conjunction with substance abuse and physical violence, was normal and normative; they also understood that they needed to protect themselves from verbal assault, physical punishment, abuse, neglect, or serious injury by adults. Often adults were oblivious to the linguistic modeling function perceived by children as they joked and argued. Likewise, they were unaware that their actions provided a direct model for interpersonal interaction.

Lies and Stories Told to Children

Finally, children were told lies or stories and watched to see how long they took to understand the lie. An example occurred when Ross told Norman as a child that the roaches in the South were different from those in New York; the former had knee caps. Norman believed this to be true. As an adult, Norman mentioned this in a conversation, and everyone laughed at him. The tragedy was that Norman had been told this, and many other stories as a child and had believed them for many years. Often adults misled children in jest to see how long before they figured the story out. But adults also routinely forgot that they had given the misinformation and never communicated the truth. So children grew up believing ridiculous things or learning at an early age to distrust adults or to be cautious in accepting what adults told them.

Sometimes the adults accepted certain lies or superstitions as fact. Their own parents or relatives had believed in these things and passed along this information to them; likewise the present generation of adults imparted this information to their children and others. For example, an adult respondent in a related study (Rath, 1992) honestly believed that opening an umbrella inside the house would bring her bad luck. Her friend, who was part of the conversation, said, “Where did you learn that? How else are you going to dry out an umbrella?”

NONROUTINE EVENTS

A funeral is typically a time when family/kin come together to mourn their loss and reaffirm their ties. But major life events also illustrate when and to whom it is acceptable to use some forms of violence.

LaTisha’s funeral and wake demonstrated the process by which children observed adults’ expressions of anger and extreme aggression. Although family members firmly disapproved of Barbara’s fighting LaTisha when she was alive, little was said or done about it at the time. News of their continuing argument passed very rapidly among family/kin and friends. Although family members continued to interact with Barbara, they talked about her in a derogatory manner when she was not present. While the family knew that LaTisha was in poor health, nevertheless, key family members blamed Barbara for “causing” her mother’s death. Their disapprobation of Barbara can be seen as a belated attempt to let other family members—particularly children and adolescents—know that there were limits on negative behaviors they would tolerate and to affirm respect for one’s parents as a basic value. Breaching this value required special sanctions.

At the wake, John told Barbara that when she died, he would insist upon an autopsy in order to see what “you got in your head for a brain.” He also stated, “I will not do anything for you,” and “Never come to me for anything.” When Barbara addressed him as “grandfather,” he replied, “Do not call me grandfather”—displaying his strong disapproval of Barbara fighting with LaTisha. Other family members also demonstrated their disapproval of Barbara’s fighting with her mother.

The family responded to Barbara’s transgression at the wake when Barbara was “punished” by Sonya. The following fieldnote illustrates the aggressive way that key family members conveyed their collective disapproval of Barbara’s fighting her mother, by further aggression and near violence:

This gathering after the funeral grew into a very tense situation. Sonya was with one of her boyfriends whom she continued to hug and kiss excessively. He was extremely skinny and had needle marks on his arms. He had a smile that seemed to be plastered on his face. When he first came in, Sonya went in the back and changed into a red two-piece suit, white blouse and red shoes. They disappeared together and Sonya came back smiling. She changed clothes a few times. As a record played, Sonya and the boyfriend fell out of the chair and on to the floor from her dancing in his lap and grinding his thigh. Sonya related to me that he made sure she was all right. I am sure this meant that he was her drug man because she said that he had taken care of her (as she said this she began to smile) and that she felt better ….

Sonya had been crying because LaTisha was her close friend and same-age cousins. They had taken various drugs together, they had used heroin together. LaTisha was the one who had shown Sonya how to use drugs and they had shared an apartment together at one point in time.

After a while Sonya screamed and cursed at Barbara, “You killed my buddy, motherfucker.” Sonya pulled up her dress and turned her buttocks and stuck them in Barbara’s face and told her, “Kick my ass, yea, you a bad bitch. Slide [fight] me now. Jump bad motherfucker and kick my ass. You so bad, jump my way, stomp on me, get a fucking broom and beat me.” She called Barbara every (curse) name she could think of. “You fucked up whore, kiss this ass, kick this ass Do anything you feel you big enough to do to this ass right now and right here.” Sonya continued to pace the floor in front of Barbara, threw up her dress and smacked her behind inviting Barbara to kiss it, kick it, or touch it in any way. Sonya jumped up and down, screamed obscenities and walked the floor, ran close in Barbara’s face, threw her hands close to Barbara, screamed and cursed, and invited Barbara to hit her.

Sonya wanted to beat Barbara for LaTisha. The family and close friends talked about Barbara fighting LaTisha; now Sonya acted out how everyone felt. Everyone sat and watched this episode. No one said anything to either Sonya or Barbara but showed no sympathy for Barbara. Barbara did not say anything. She permitted Sonya to say and do what she wanted. Everyone was pleased that Sonya let Barbara know how they felt. Everyone silently agreed with every word and action Sonya acted out. The family and friends agreed that Barbara needed this public humiliation. Once Sonya finished, she left with her boyfriend.

Sonya used aggressive behavior, ritual insults, and threats of violence toward Barbara to emphasize family values and to punish Barbara for her violent conduct towards her mother. Such aggressive behavior was sanctioned by the family as a form of retribution. Verbal threats did not escalate into physical aggression until family members mixed alcohol and drugs. In other words, when adults were relatively sober, verbal aggression—just short of physical violence—took place at an event where some amount of respectful behavior was thought to be warranted. When adults became “high,” however, fights and arguments broke out among family and friends.

For example, much of the conversation at the gathering after LaTisha’s funeral was about “the fight” on the previous night at the wake. Those attending the funeral related that the wake had turned into an intense event lasting until 6 a.m. and that the fight occurred late in the evening when most of the adults were high from consuming some substance. Family members, friends, and acquaintances of LaTisha had been present. The wake ended early in the morning with the house in shambles. So much fighting had occurred that mirrors in the hallway of the apartment were broken. Friends of the family, who had came by to show their respect, were extremely cautious at the gathering after the funeral because of the extent of violence at the wake. Chevis, a friend of the family, would not leave the kitchen at the gathering after the funeral because so much fighting had occurred at the wake, and he did not want to get caught in between disturbances that might arise. During this event, children had been present and had observed heavy substance use, profanity, arguments, dancing, and fights among family members, but the adults had been so caught up in all of this that they did not notice where children were located when they fought.

The funeral and wake illustrate how violence is sanctioned and normalized in times of crisis within this particular subculture. The adults modeled aggressive language and violent behaviors which they made no attempt to hide, suggesting to the children present that these were acceptable and normal.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This case study of the Jones and Smith family used illuminating episodes to provide snapshots of the kinds of environments that existed when drug abuse was a major activity among adults in family life. While the African-American family and extended kin network has provided exceptional flexibility and adapted to changing conditions (Herskovits, 1941 [1990]; Stack, 1974), this research noted the difficulties where heavy drug and alcohol abuse by significant household adults was present.

When consumption of drugs by adults was all encompassing, the bulk of family resources—emotional, financial, investment of time, and material—went towards the acquisition and consumption of substances. This appropriation of resources represented an insidious form of violence against the entire family and resulted in varied forms of neglect and abuse of children. A number of examples can be found in this kin network (see Johnson, Dunlap & Maher, in press). When Island was not available to supervise him, Daniel (at age two) “hung around” with “uncle” Ross and his selling associates as they sold drugs. Likewise, “Aunt” Sonya would “whup” him when he behaved like a two-year old; she would spank, hit, or aggressively curse at him (as she would her adult associates). Likewise, Norman had been sexually abused and severely neglected by his mother, LaTisha while growing up. May and Janet were expected not to bother adults who were drinking or using drugs; they were ignored by or whipped for bothering adults while using drugs or alcohol.

The resulting family environment was typically one having marginal connection with any part of conventional society, and having an overall lack of positive role models and mentors. Only Grandfather John had legal employment and connections to conventional society. Yet none of his children as adults were employed, most were prostitutes, addicts, criminals, as were the children reaching young adulthood. Responsibility for rearing grandchildren (and fourth generation children, like Daniel) fell upon the grandparents (like Island or John) or a relatively noncriminal middle aged adult (like Judy or Kim) who may not be related to the child(ren) they were rearing or by the foster care system.

Thus, the Jones and Smith families can be viewed as a training ground for violence and aggression (Straus, Gelles & Steinmetz, 1980) through the modeling, teaching, and reinforcement of such behaviors. Indeed, routine social modeling of behavior by adults (Campos & Steinberg, 1981; Schreiber, 1992) provided critical social learning experiences (Bandura, 1973) for children in these households. What they observed were numerous and varied forms of aggression and violence which took place on a regular basis within these households and kin networks. Violence, the threat of violence, verbal aggression, and drug use routinely provided the negative context in which developing children learned to interact with others. Since adults often acted out aggressive and violent behaviors in the presence of children or while interacting with them, children learned these behaviors primarily through modeling. Often, Daniel’s direct caregivers were Ross, a crack seller, and Sonya, a crack prostitute. Daniel was learning from Ross and Sonya how to be (and was becoming) a “bad ass” at age two; his early words included many curse words, how to yell loudly, be aggressive, hit to resolve conflicts, and to recognize drug induced states.

Moreover, when children were ignored, treated in negative and violent ways, or otherwise treated with limited respect, this distorted the ways that they learned to handle simple interactions, such as meeting people and establishing relationships with others. Rather, children (like Janet and May) learned to “stay out of the way” of adults. But children also learned to defy adult commands to gain adult attention and substitutes for true affection; but they risked being cursed at or whipped by their caregiver (see Johnson, Dunlap & Maher, in press).

Moreover, this pattern of mother-child violence sometimes continued and often intensified when the child reached adulthood. On many occasions prior to her death, LaTisha (mother) was observed prostituting together with her daughter, Barbara. At no time was either woman observed to verbally express [conventional forms of] affection (e.g., saying “I love you, mom” or hugging the other). While working (prostituting), they were routinely observed arguing, fighting, hitting, and even “cutting” each other over money or crack—but both women actually equated such behaviors as expressions of affection to and from the other. Thus, in their thinking, a “fight” was equal to “loving” the other. Likewise, in their twenties, Sonya and LaTisha lived together, prostituted together, used drugs together, and fought together. In short, they had considerable affection for each other—but direct verbal expressions of affection were not expressed directly and unconditionally. Overall, the complex nature of these inter-generational patterns of aggression and violence became evident when LaTisha’s history of violence toward her daughter in childhood and young adulthood culminated in Barbara’s eventual use of violence towards her mother, ending with the mother’s death.

Since violence and aggressive languaging were a part of everyday interaction, individuals were not comfortable interacting with other persons in any other manner. Barbara demonstrated this in her relationship with her boyfriend when she could not accept love and compassion. In turn, the kin network used aggression as punishment (e.g., Sonya after the funeral) to teach Barbara a “lesson” of not using violence toward a parent.

These familial patterns of expressing affection via aggressive languaging and fighting were also carried into interactions with others outside the kin network. This was most evident in how both Sonya and Barbara related to the boyfriends with them at the wake. The women swore at, cursed, and belittled the boyfriends; all verbal expressions to the boyfriends were explicitly sexual or about sharing drugs, as were their behaviors (lap dancing and grinding of thighs).

These families also exhibited tow cohesion and high intra-familial conflict as evidenced in their testing and insults. This low cohesion was constantly exhibited during LaTisha’s wake as when Kim made jokes and double edged jibs at how poorly Judy was feeding Janet and May, and then tried to gain allies among other adults, and by involving Janet in the dispute. Another example was when John bought alcohol which he knew that Kim (the hostess) and others did not like. Kim also commented how no one else was paying for any food (all families were very poor). Ironically, the greatest sense of family cohesion emerged during the “near violent event” when Sonya publicly humiliated Barbara at the wake. Sonya expressed the family’s collective disapproval of Barbara’s “fighting” with her mother—something all family members had observed mother and daughter doing many times before.

The interaction patterns of this family, as illustrated by episodes occurring around LaTisha’s death, were dominated by abuse, aggression, and violence. Family members demonstrated a lack of compassion, harsh treatment during vulnerable moments, and aggressive language during sensitive episodes. Such incidents reveal the values, expectations, and patterns of aggression of the family and illustrate the ordinary context in which the social learning and modeling of violence takes place.

Moreover, the lengthy history of alcohol and drug abuse in the Jones and Smith family placed the entire kin network under considerable economic and emotional stress for generations. John and his fictive wife Judy, were heavy alcohol consumers. All of John’s children abuse and/or sell some type of illicit drug. John’s siblings and their offspring were also heavily involved in alcohol/drug consumption. LaTisha’s relations with her children clearly illustrated the destructive role of drugs in promoting violence and aggression in family life. LaTisha introduced her children to the drug culture and in so doing (especially with other family/kin involved) immersed them in an environment where drug consumption was seen as routine and normal. And children were often present when violence and drug use among adults took place; often children were the object of such violence.

Many times, violence and aggression spawned in one household infiltrated the kin network, drawing other households into the confusion—as demonstrated when Elmira removed Tony after he raped his sister and then imposed Tony on LaTisha and Theodore’s household. Furthermore, children were often moved between households and among caregivers, prompted by neglect, aggression, and violence in parent-child relations. In fact, all the children in the Jones and Smith family who were born in LaTisha’s generation and especially in Barbara’s generation, were moved back and forth between relatives and/or to strangers in the foster care system. This lack of household and caregiver stability provided an early introduction to what often became lifelong uncertainties and insecurities.9 LaTisha’s son, Norman, represented ah extreme case of parental abuse and continuing neglect in childhood, shifting guardianship during adolescence (including the foster care system), homelessness as a young adult, and long term imprisonment for a violent crime in his early 20s. Through constant movement among caregivers, children sometimes ended up residing with the same family members that earlier perpetrated neglect and possibly abuse against their parents (Dunlap, 1992; Johnson, Dunlap & Maher, in press).

In addition, the family lived in an inner-city neighborhood where there was a high level of drug abuse and violence in many other families and households. Thus, within both the family unit and outside of it, children were not routinely exposed to the nonviolent and nonaggressive behavioral patterns by which conventional society usually operates.

In short, the illuminating episodes here suggested some of the mechanisms by which violence and aggressive behaviors had become institutionalized within families. Aggression and violent behavior, along with drug consumption and sale, was entrenched in the Jones and Smith family (and many other similar inner-city family units). Family members expressed their values, beliefs, and expectations about aggression and violence during special occasions and events in everyday life. Within this context, children learned that such behavior was normal and expected. They likewise accepted drug use as a normal activity, thus facilitating their later participation in the drug subculture. Moreover, these aggressive/violent patterns had often worsened among successive generations (Butterfield, 1995) such that by the 1990s, aggression and violence had become so deeply entrenched within families with adult drug abusers that entire kin networks could not comprehend the existence of nonviolent alternatives.

In fact, the most important ingredient of successful (conventional) families was almost entirely absent in the Jones and Smith households where the adults did not and (for the most part) could not create a warm, supportive, and intimate environment for their children and others (Straus & Hotaling, 1980; Dunlap, 1992, 1995; Dunlap & Johnson, 1992; Johnson, Golub & Fagan, 1995; Johnson, Dunlap & Maher, in press).

In sum, this paper illustrated some of the social processes in which adults in the Jones and Smith family modeled aggressive and violent behavior while interacting with one another and with their children. Violence and aggression by adults combined with substance abuse, the neglect and abuse of children, aggressive and profane verbal communication, and destructive gender relations form a web of familial social interactions that serve to reproduce such behaviors inter- and intra-generationally. Although one or more strands of this web may be evident in nonsubstance abusing families, the destructive nature of these social interactions and their cumulative effects within substance-abusing households ensured that the transmission of violent and aggressive behaviors will continue in the future.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (1R01 DA 05126-08, 5R01 DA 09056-03, 5T32 DA07233-13) and a NIDA Minority Research Supplemental Award (1R03 DA 06413-01). The opinions expressed in this paper do not represent the official position of the U.S. Government, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., or Medical and Health Research Association of New York City, Inc.

The authors acknowledge the many contributions to this research made by Phyllis Curry, Richard Curtis, R. Terry Furst, Douglas Goldsmith, Andrew Golub, Ansley Hamid, Lisa Maher, Ali Manwar, Jennifer Milici, Doris Randolph, Stephen Sifaneck, Charles Small, and Damaris Westley.

NOTES

All of the names are pseudonyms.

Gelles (1987:15) identified eleven factors: time at risk, range of activities and interests, intensity of involvement, impinging activities, right to influence, age and sex differences, ascribed roles, privacy, involuntary membership, stress, and extensive knowledge of social biographies.

Staub (1996) writes that “The modeling of violence—by parents, in the neighborhood, and on television—increases aggression.”

Island actually had a different mother and father than John, but she was raised as a (fictive) sister by John’s mother. There were four other siblings in their family, occasionally present in the episodes described below. John and Island have also cared for other kin from their respective spouse’s children.

Barbara’s son was removed from her care by the child welfare agency at birth. She knows nothing about his whereabouts and has taken no steps to get him back. See Maher (1991) regarding efforts by the state to regulate motherhood among crack abusers.

Future papers will elaborate on how these family systems socialize girls for early sex, early childbirth, and early onset to prostitution.

Incidentally, after LaTisha’s death, Elmira took Tony back into her household.

This represents a new type of living arrangement that many crack-using women have created for themselves. See Dunlap and Johnson (1992), Hamid (1992), and Maher, Dunlap and Johnson (1996) for more examples.

Widom (1992:5) found that children who had moved three or more times had significantly higher arrest rates (almost twice) for all types of criminal behavior.

Contributor Information

ELOISE DUNLAP, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc..

BRUCE D. JOHNSON, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc.

JULIA W. RATH, Medical and Health Research Association of New York City, Inc.

REFERENCES

- Aschenbrenner J. Lifelines: Black families in Chicago. Waveland Press; Prospect Heights, IL: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Aggression: A social learning approach. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Ross D, Ross S. Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggresive models. Journal of Abnormal Sociology and Psychology. 1961;63:575–582. doi: 10.1037/h0045925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biringen Z, Robinson J. Emotional availability in mother-child interactions: A reconceptualization for research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61(2):258–271. doi: 10.1037/h0079238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Dunlap E. Exorcising sex-for-crack: An ethnographic perspective from Harlem. In: Ratner M, editor. Crack pipe as pimp: An eight-city study of the sex-for-crack phenomenon. Lexington Books; New York: 1993. pp. 97–132. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield F. All God’s children: The Bosket family and the American tradition of violence. Alfred A. Knopf; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Steinberg C. Perception, appraisal, and emotion. In: Lamb L, Sherrod J, editors. Infant social cognition. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Dertke M, LaVoie L, Borders S, Washburn M, Schmeidler J. Physical abuse sexual victimization and illicit drug use: A structural analysis among high risk adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1987;10:13–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(87)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Frame CL. Social cognitive biases and deficits in aggressive boys. Child Development. 1982;53:620–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs WR, Miller BA, Gondoli DM. Childhood experiences of parental physical violence for alcoholic women as compared with a randomly selected household sample. Violence and Victims. 1987;2(4):225–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E. Shifts and changes in drug subculture norms and interaction patterns. Paper presented at the American Society of Criminology; San Francisco, CA. Nov, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E. Impact of drugs on family life and kin networks in the inner-city African-American single-parent household. In: Harrell A, Peterson G, editors. Drugs, crime, and social isolation: Barriers to urban opportunity. Urban Institute Press; Washington, DC: 1992. pp. 181–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E. Inner-city crisis and drug dealing: Portrait of a drug dealer and his household. In: MacGregor Suzanne, Lipow Arthur., editors. The other city: People and politics in New York and London. Humanities Press; New Jersey: 1995. pp. 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E, Johnson BD. The setting for the crack era: Macro forces, micro consequences (1960-1992) Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;4(24):307–321. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E, Johnson BD. Gaining access and conducting ethnographic research among drug dealers and their families in the inner city. Presentation at the Society for Applied Anthropology; Cancun Mexico. Apr, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E, Johnson BD, Sanabria H, Holliday E, Lipsey V, Barnett M, Hopkins W, Sobel I, Randolf D, Chin K. Studying crack users and their criminal careers: The scientific and artistic aspects of locating hard-to-reach subjects and interviewing them about sensitive topics. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1990;17(1):121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Scoufe A. Developmental sequelae of maltreatment in infancy. In: Rizley R, Cicchetti D, editors. Developmental perspectives on child maltreatment: New directions for child development. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1981. pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN. The affective self: Continuities and transformation from infancy. In: Call J, Galenson E, Tyson R, editors. Frontiers of infant psychiatry. vol. 2. Basic Books; New York: 1985. pp. 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Drug selling and elicit income in distressed neighborhoods: The economic lives of street-level drug drug users and dealers. In: Harrell Adele, Peterson George., editors. Drugs, crime, and social isolation. Urban Institute Press; Washington, DC: 1992. pp. 99–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Women and drugs revisited: Female participation in the cocaine economy. Journal of Drug Issues. 1994a;24(2):179–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Do criminal sanctions deter drug crimes? In: MacKenzie Doris L., Uchida Craig., editors. Drugs and the criminal justice system: Evaluating public policy alternatives. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1994b. pp. 188–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan JA, Chin K. Violence as regulation and social control in the distribution of crack. In: De La Rosa M, Lambert E, Gropper B, editors. Drugs and violence. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1990. pp. 8–43. [Research Monograph] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson RB, Tedeschi JT. Aggression and violence: Social interactionist perspectives. American Psychological Association; Hyattsville, MD: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Feshbach S. Child abuse and the dynamics of human aggression and violence. In: Gerbner J, Ross CJ, Zigler E, editors. Child abuse: An agenda for action. Oxford University Press; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. Sexually victimized children. The Free Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Frodi A, Smetana J. Abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated preschoolers’ ability to discriminate emotions in others: The effects of IQ. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1984;8:459–465. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(84)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabarino J, Platz MC. Child abuse and juvenile delinquency: What are the links? In: Garbarino J, Schellenbach C, Sebes J, editors. Troubled youth, troubled families. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 1986. pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]