Hurricane Katrina displaced approximately 650,000 people and destroyed or severely damaged 217,000 homes along the Gulf Coast. Damage was especially severe in New Orleans, and the return of displaced residents to this city has been slow. The fraction of households receiving mail (which, in the absence of reliable population estimates, is a good indicator for returns) was 49.5 percent in August 2006, and 66.0 percent in June 2007 (Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, 2007). Low-income minority families appear to have been slower than others to return (William H. Frey and Audrey Singer, 2006).

In this paper, we examine the determinants of returning to New Orleans in the 18 months after the hurricane. The data come from a study of low-income parents—mainly African American women—who were enrolled in a community college intervention prior to the hurricane. Although the sample is not representative of the pre-Katrina population of the city, it nonetheless is of great interest. The relatively slow return of low income, primarily African American, residents is a politically charged issue. One (extreme) view is that the redevelopment plans are designed to discourage low-income minority residents from returning. A quite different view is that members of this group have found better opportunities outside of New Orleans, and do not want to return. Because few data sets trace individuals from before to after the hurricane, this debate has taken place largely without the benefit of evidence.

I. Theoretical Framework

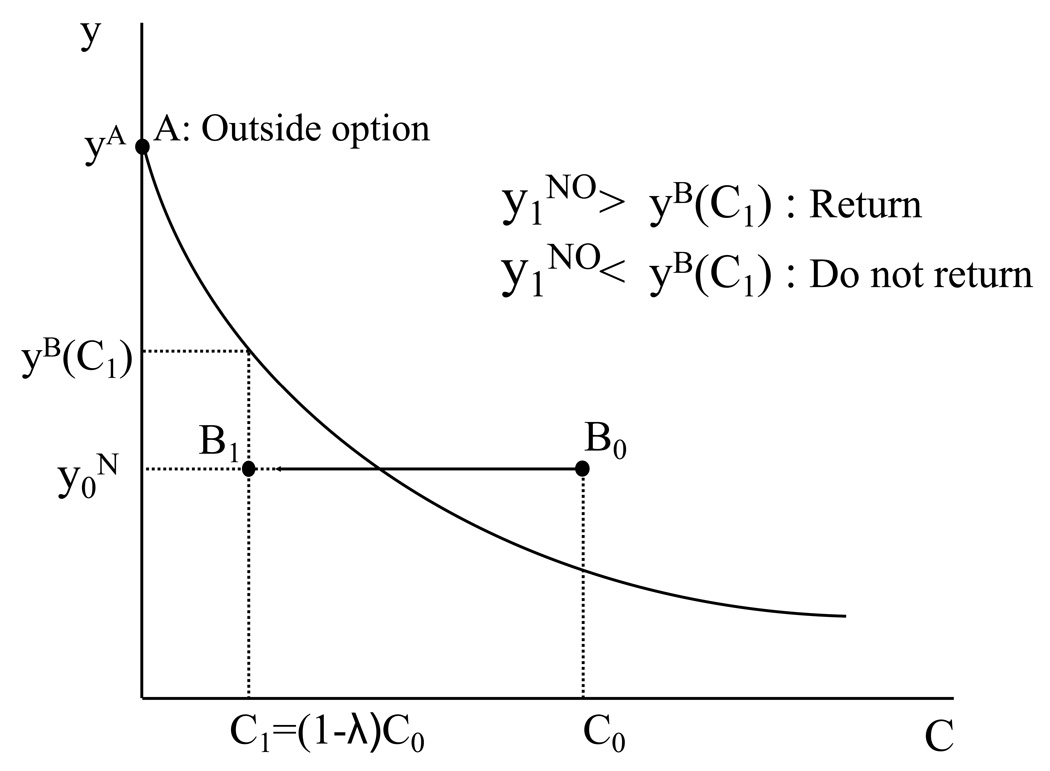

We present a simple model of the return decision that is used to motivate the empirical work that follows. Individuals’ utility is assumed to be a function of their level of income, y, and their stock of location-specific capital, C. Location-specific capital is defined as aspects of homes, communities, and networks of friends that are not easily replaced in other cities, at least in the short run. Note that location-specific capital does not include financial assets or easily-replaced personal property. Losses in these assets produced by the hurricane are sunk costs that should not affect the location decision. Location-specific capital (and losses of this type of capital) can, in contrast, affect the value of living in one location relative to another.

An individual who lives in New Orleans receives income yNO and has a location-specific capital level of C. If she were to leave New Orleans, she would receive an income of yA and have a location-specific capital level of zero. Figure 1 depicts an indifference curve that traces the set of points at which an individual is just indifferent between staying in New Orleans and leaving. This indifference curve specifies a set of “break even” income levels for each value of C, denoted as yB (C). Given a value of C, an individual with yNO that exceeds yB (C) remains in New Orleans. If not, she leaves the city, moving to Point A with income equal to yA and C equal to zero. The figure emphasizes the idea that elements in C—such as networks of family a friends, and attachment to neighborhood communities—influence location decisions. For example, an individual at point B0 would receive a higher income outside of New Orleans, but chooses to stay because of her high level of location-specific capital.

Figure 1.

Hurricane Katrina is modeled as having two effects. First, individuals experience losses to their location-specific capital based on the degree of destruction from the hurricane. Let λ denote the fraction of capital that is destroyed, so that the new value of location-specific capital is C1 = (1 − λ)C0. Second, the hurricane disrupts employment, so that individuals receive a new draw from the distribution of earnings that prevails in the city after the hurricane. Individuals receive this new draw because jobs are destroyed, wages within jobs change, or individuals who return have the opportunity to take jobs that are left vacant by those who have not returned. (In our sample, only 48 percent of those who return to New Orleans work for a former employer.) For simplicity, we assume that y A is unaffected by the hurricane. An individual returns if the new draw on income in New Orleans offsets the destruction in location-specific capital produce by the storm. In the example shown in the graph, the individual returns to New Orleans only if the income she would receive in New Orleans after the hurricane exceeds yB ((1−λ)C0).

Several comparative statics results are evident from the figure: (1) the probability of returning is decreasing in outside income yA, conditional on the level of post-hurricane location-specific capital; (2) the probability of returning decreases with the level of destruction of the location-specific capital (λ), holding C0 fixed; and (3) the probability of returning increases with C0, holding λ fixed. There may also be interactions between λ and C0. For example, initial location-specific capital may have little effect on return decisions for those with very high values of λ In the extreme, if λ is equal to 1, location-specific capital after the hurricane will equal 0 and location decisions will be made solely on the basis of relative incomes.

II. Empirical Analyses

Sample members were participants in an on-going study of low-income parents who had enrolled in two community colleges in the City of New Orleans in 2004–2005. The purpose of this randomized study was to examine how incentive-based scholarships influence academic achievement and wellbeing. Baseline information was collected for the 1,014 participants in the study. When Hurricane Katrina struck, 492 participants had completed a 12-month follow-up survey, which collected information on participants’ economic status, social support and health.

After Hurricane Katrina, we attempted to re-interview these 492 participants via a telephone survey conducted between May 2006 and March 2007. We located and surveyed 402 participants for a final response rate of 81.7%. We also geocoded the addresses at which they lived at the time of the 12-month interview, and matched addresses to water depth data from September 2, 2005, the day on which standing water levels in the city are estimated to have peaked.1 (We use self-reported water depths for the 15 respondents whose addresses were P.O. boxes.) Water depths indicate whether respondents lived in hard-hit areas. Our analyses are based on 355 participants, 96 percent of whom are women, who lived in the New Orleans MSA before the hurricane. Although the sample is small, it is unique as we have pre-Katrina data four sample (See Craig Landry et al (2007) for studies based on samples without baseline data.)

Table 1 shows sample means and standard deviations (in parentheses), for the full sample and for those who had and had not returned to the New Orleans MSA by the time of the follow-up survey (Only 8 sample members said they did not evacuate from their homes because of the hurricane; we do not have evacuation information for an additional 5.) All variables except water depth were measured prior to the hurricane. Those who had returned (49.6 percent of the sample) were significantly less likely than others to be black, and more likely to have lived in the homes of friends or relatives or to have owned their own homes than to have been renters. There is a striking difference in the amount of flooding experienced between those who did and did not return: 23.9 percent of those who returned had positive levels of flooding four days after the hurricane struck, compared to 58.7 percent of those who did not return.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Full sample | Returned | Not returned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race is black | 0.820 | 0.733 | 0.905* |

| Married or cohabiting | 0.245 | 0.233 | 0.257 |

| Number of children | 1.93 (1.06) |

1.847 | 2.017 |

| Owned Own Home | 0.130 | 0.170 | 0.089* |

| Lived in home of friends or relatives | 0.146 | 0.199 | 0.095* |

| Attended church at least once/month | 0.704 | 0.676 | 0.732 |

| Social support scale (z-score) | 0.000 (1.000) |

0.020 | −0.020 |

| Indicator: Water depth>0 | 0.414 | 0.239 | 0.587* |

| Water depth (feet) | 1.66 (2.41) |

0.978 | 2.338* |

Notes: The sample contains 355 observations, of which 176 had return 179 had not. Race categories not shown include “white” (9.3 percent), “other” (4.8 percent) and “not reported” (3.9 percent).

Values for those who did and did not return are significantly different at the 5-percent level better.

We examine whether returns are positively associated with less hurricane damage and greater pre-hurricane levels of location-specific capital. Our primary measure of hurricane damage exposure (λ) is an indicator of whether the water depth was positive. We use four measures of location-specific capital, all of which were measured prior to the hurricane. The first is an indicator for whether the respondent owned her own home, and the second is whether she lived with friends or relatives. If housing markets function perfectly, homeownership per se should not be a measure of location-specific capital. However, this seems unlikely to be the case. In addition, home owners may be more likely to be attached to neighborhoods than renters. Living with friends or relatives may also indicate that the respondent has social ties in New Orleans. The third measure is an indicator of whether the respondent attended church frequently, which indicates the presence of a social network in New Orleans. The last measure is an 8-item social support scale that contains items such as “There are people I know will help me if I need it,” (C.E. Cutrona and D. Russell, 1987). Each item is coded on a 4-point scale, summed, and then converted from the final scale to a within-sample z-score.

Table 2 shows the results of OLS regressions of an indicator for having returned to the New Orleans MSA on the variables of interest and demographic controls. Results for the full sample, shown in the first two columns, indicate that those who lived in flooded areas were between 30 and 40 percentage points less likely to return. Regressions (not shown) that include dummies indicating the respondents’ parish or (if the parish is Orleans) ward, yield similar results. We also found that the return decision is based more on whether there was flooding than on the amount of flooding: in a regression that included both the indicator that water depth was positive and the water depth in feet, the coefficient on the water depth was small and insignificant. This may arise because actual water depths were imprecisely measured, or because even small amounts of standing water produced serious damage to homes and neighborhoods.

Table 2.

Dependent variable: Indicator that individual returned to the New Orleans area

| Full sample | Water depth>0 | Water depth=0 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator: Water depth>0 | −0.368*** (0.051) |

−0.320*** (0.052) |

||

| Married/cohabiting | −0.030 (0.060) |

−0.063 (0.086) |

−0.019 (0.082) |

|

| Number of children | −0.045* –(0.024) |

−0.077** (0.034) |

−0.010 (0.033) |

|

| Race is black | −0.204** (0.090) |

0.047 (0.036) |

−0.204** (0.095) |

|

| Attended church at least once/month | −0.078 (0.054) |

0.042 (0.079) |

−0.173 (0.074)** |

|

| Social support scale | −0.009 (0.025) |

0.031 (0.037) |

−0.055 (0.034) |

|

| Owned Own Home | 0.175** (0.077) |

0.163 (0.122) |

0.235** (0.103) |

|

| Lived in home of friends/relatives | 0.096 (0.072) |

−0.064 (0.132) |

0.206** (0.087) |

|

Notes: Regressions include a male dummy, the number of months between the hurricane and interview, indicators that race is “other” or “missing,” and (for column 3) water depth.

Significant at the 1-percent level

the 5-percent level

the 10-percent level.

Respondents with more children were less likely to return, possibly because schools were slow to reopen. African Americans were also less likely to return, even controlling for water depth. (Note that African Americans were more likely than others to have experienced flooding: 45.0 percent of blacks had positive flooding, relative to 25.0 percent of others.) Relative to renters, homeowners were nearly 18 percentage points more likely to return, and those living with relatives or friends were 9.6 percentage points more likely to return. However, the coefficients on “attended church frequently” and the social support scale are negative statistically significant. Nevertheless, the location-specific capital variables are jointly significant at the 3 percent level.

Our theoretical framework implies that there may be interactions between the amount of damage (λ) and the location-specific capital variables. We examine this by estimating separate id and did not experience flooding shown in the last two columns. Consistent with the framework, the location-specific measures do not predict returns among those who experienced flooding (i.e. those with values of λ) Furthermore return decisions among those who did not experience flooding (i.e. those with low values of λ)are sensitive to several demographic characteristics and location-specific capital measures, although not always in the ways expected. As expected, homeowners and those who lived with relatives or friends were significantly more likely to return than renters. However frequent church attendees were 17.3 percentage points less likely than others It may be that respondents’ churches were destroyed by the hurricane, even if their homes were not making it less attractive to stay in New Orleans. It may also be that responds with ties to churches found it easier to develop social networks in new cities. This latter interpretation suggest that church involvement represents “portable” rather than location-specific capital.

We expect that those with better economic opportunities outside of New Orleans will be less likely to return. To examine whether this is the case, we used data from the 2000 Census to construct a measure of yA equal to average weekly earnings of low-skilled workers in the locations in which individuals had lived just prior to returning to New Orleans or, for those who had not returned, in their locations at the time of the survey. We estimated models that included this measure, as well as the individual’s monthly earnings in New Orleans prior to the hurricane to proxy for earnings potential in New Orleans. The coefficients on both variables were small and insignificant. However, it is possible that these variables are very inaccurate measures of economic opportunities in New Orleans and elsewhere.

III. Discussion

The results shown above indicate that flood exposure is the single most important factor in determining the decision to return. Yet, 36 percent of those who experienced no flooding had not returned to the New Orleans area by the time of the follow-up survey. Among those who did experience flooding, those who did not own homes or lived in the homes of relatives or friends were less likely to return. Those who attended church frequently were, somewhat surprisingly also less likely to return.

The framework developed above implies that the losses from the hurricane should be largest among those who experienced more hurricane damage. However, some evacuees may have been unaware, prior to the hurricane, that better economic and social opportunities were available in other locations. If so, the forced movement out of the city due to the hurricane could have resulted in welfare improvements.

We do not find evidence to support this idea. We divided individuals into four groups, defined by whether the person returned, crossed with whether the person experienced flooding, and computed mean changes in monthly earnings from before to after the hurricane for each group. Those who experienced flooding and did not return had reductions in earnings that were on average $192 larger than members of the other three groups. (Earnings changes for members of the other three groups were not significantly different from each other.) Although we do not know what members of this group would have earned had they returned to New Orleans, it is not the case that their financial circumstances improved after Hurricane Katrina.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from NIH/NICHD (R01 HD046162) and the MacArthur Foundation, and thank Emily Buchsbaum, Enkeleda Gjeci and Sahil Raina for excellent research assistance, and Sheldon Danziger for useful comments.

Footnotes

This paper was prepared for the 2008 AEA meetings in New Orleans, LA.

These data are distributed by the LSU GIS Information Clearinghouse: CADGIS Research Lab, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA. 2005/2006, http://www.katrina.lsu.edu.

Contributor Information

Christina Paxson, Center for Health and Wellbeing, Princeton University.

Cecilia Elena Rouse, Industrial Relations Section, Firestone Library.

References

- Cutrona CE, Russell D. The Provisions of Social Relationships and Adaptationto Stress. In: Jones WH, Perlman D, editors. Advances in Personal Relationships. Vol. 1. Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press; 1987. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Landry Craig E, Bim Okmyung, Hindsley Paul, Whitehead John C, Wilson Kenneth. “Going Home: Evacuation-Migration Decisions of Hurricane Katrina Survivors.”. Southern Economic Journal. 2007;74(2):326–343. [Google Scholar]

- Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. “The New Orleans Index: Tracking Recovery of New Orleans and the Metro Area.”. New Orleans: Greater New Orleans Community Center. 2007. http://www.gnocdc.org/NOLAIndex/NOLAIndex.pdf.

- Frey William H, Singer Audrey. “Katrina and Rita Impacts on Gulf Coast Populations: First Census Findings.”. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution; 2006. [Google Scholar]