Abstract

We sought to determine the relationship between lung size and airway size in men and women of varying stature. We also asked if men and women matched for lung size would still have differences in airway size and if so where along the pulmonary airway tree would these differences exist. We used computed tomography to measure airway luminal areas of the large and central airways. We determined airway luminal areas in men (n = 25) and women (n = 25) who were matched for age, body mass index, smoking history, and pulmonary function and in a separate set of men (n = 10) and women (n = 11) who were matched for lung size. Men had greater values for the larger airways and many of the central airways. When male and female subjects were pooled there were significant associations between lung size and airway size. Within the male and female groups the magnitudes of these associations were decreased or nonsignificant. In males and females matched for lung size women had significantly smaller airway luminal areas. The larger conducting airways in females are significantly smaller than those of males even after controlling for lung size.

Keywords: airway luminal area, airway-parenchymal dysanapsis, three-dimensional computed tomography

the concept that airway size is not necessarily related to lung size was first proposed by Green et al. (12). The wide variation in maximal expiratory flow rates between individuals with similar lung size was interpreted to mean that there is no consistent association between lung and airway size. Subsequent to this, the term “dysanapsis” has been used to reflect unequal growth and express the physiological variation in the geometry of the tracheobronchial tree and lung parenchyma due to different patterns of growth. Mead (27) determined the association between airway size (estimated using maximal expiratory flow/static recoil pressure at 50% vital capacity) and lung size (estimated using vital capacity) in adult women and men. It was found that healthy adult men have airways that are 17% larger in diameter than are the airways of women. Moreover, it was concluded that women and boys have airways that are smaller relative to lung size compared with men; therefore, the apparent sex-based differences occur late in the growth period. Additional support for the concept of dysanapsis comes from studies that have made acoustic reflectance estimates of tracheal area in young healthy men and women (23). In a subset of subjects matched for total lung capacity, Martin et al. (23) found that the tracheal cross-sectional area was 29% less in women compared with men. As such, there are significant male-female differences in tracheal size that do not appear to be explained by lung size.

While previous studies have provided insight into potential sex-based differences in the relationship between airway size and lung size, they have been limited either by the use of indirect estimates of airway size (12, 27) or by the use of an examination of the airways above the tracheal carina (13, 14, 19, 23). In addition, the majority of these studies have not made comparisons between men and women of equal size, making interpretation of potential airway differences difficult. As such, the purpose of this study was twofold. First, we sought to determine the relationship between lung size and airway size in men and women of varying stature. Second, we asked if men and women matched for lung size would still have differences in airway size and if so where along the pulmonary airway tree would these differences exist. To this end, we used computed tomography (CT) in men and women to provide quantitative measures of airway luminal areas. The larger conducting airways are defined as generations 0 through 16 (18). In this study we reported data for airways up to segmental bronchi (generation 3), which we have defined as the large and central airways.

METHODS

Subjects.

A total of 57 (28 male, 27 female) subjects for this study were selected from the British Columbia Cancer Agency “Lung Health Cohort” (26). The clinical ethics review boards of the British Columbia Cancer Agency and the University of British Columbia approved the study. All subjects provided informed consent to allow their spirometry and CT images to be used for research. This is a cohort of heavy smokers who have been screened for the presence of lung nodules using CT scans. All subjects were former smokers at the time of the study.

Spirometry.

Spirometry was conducted according to American Thoracic Society recommendations. The forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were recorded in liters and expressed according to predicted values (9).

Study overview.

The relationships between airway size, biological sex, and lung size were assessed in two ways. First, we measured airway luminal area (Ai) in men (n = 25) and women (n = 25) who were matched for age, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, percent predicted FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and CT measured total lung volume [expressed as % of predicted total lung capacity (TLC)]. The purpose of this approach was to examine subjects of a broad range of body heights to extend the range of lung volumes in each group. Second, we examined a separate set of men (n = 10) and women (n = 11) who were matched for lung size (estimated from FVC). The purpose of this analysis was to compare airway luminal areas in males and females with similar lung volumes to remove the independent effect from lung size and therefore reveal any sex-based difference in the relationship of airway size to lung parenchyma size.

CT scans.

All CT scans were acquired in the volume scan mode at suspended full inspiration with subjects in the supine position. No intravenous contrast media was used. These CT scans were acquired using a Siemens scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany, Siemens Sensation 16 multislice scanner, 120 kVp, 215 mA, 1.0-mm slice thickness, and a low spatial frequency reconstruction kernel, i.e., B35f) The effective radiation dose for this protocol was <1.5 mSv, providing minimal risk in this cohort of men and women aged 50–75 yr.

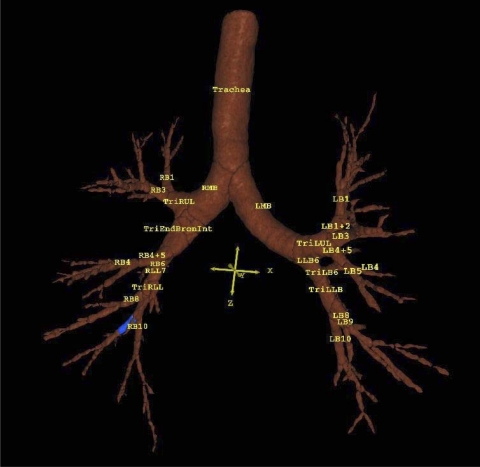

All CT scans were analyzed using Pulmonary Workstation 2.0 software (Vida Diagnostics, Iowa City, IA), and the airway tree was reformatted into three-dimensional images (Fig. 1). Briefly, lungs were segmented from the thorax wall, the heart, and main pulmonary vessels. The airways were segmented using a region-growing algorithm starting in the trachea and projecting to the smallest airway visible on the CT scan as previously described (8, 32). The lumen of the airway (Ai, in mm2), was measured for all identified airway segments at the midpoint between airway branches.

Fig. 1.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of an airway tree in a 56-yr-old ex-smoking male. Blue region represents the segment that was measured. LMB, left main bronchus; LUL, left upper lobe; LB, left bronchus; LLB, left lower lobe; RMB, right main bronchus; RUL, right upper lobe; RB, right bronchus; BRONINT, intermediate bronchus; RLL, right lower lobe; Tri, trifurcation of an airway into 3 segments.

Quantitative densitometric analysis was performed, and areas of CT emphysema were defined as low attenuation areas (LAA) less than −950 Hounsfield units (6). The percentage of LAA was used to estimate the amount of emphysema.

Statistical analyses.

Descriptive characteristics were compared between sexes using unpaired t-tests. Analysis of variance procedures were used to compare Ai values. To test for associations between selected airways and pulmonary function parameters, simple linear regression analysis using Pearson correlations were performed. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values are presented as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Subjects.

Subject characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Female and male subjects were matched for age, BMI, smoking history, and spirometry measurements. Males were significantly taller, heavier, and had larger lung volumes. Table 2 summarizes descriptive characteristics for those subjects matched for lung size. Males were slightly, but significantly, older than females. However, indexes of lung size showed that men and women were well matched. Males had a significantly lower FEV1 %predicted as we purposely selected males who were on average smaller in stature and therefore lung size.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of subjects of varying body size

| Men (n = 25) | Women (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 56.6±4.9 | 58.3±3.4 |

| Height, cm | 178.4±5.0* | 164.2±6.3 |

| Weight, kg | 88.3±11.4* | 72.3±8.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.8±3.6 | 26.9±3.3 |

| Smoking, pack-yr | 51.8±18.8 | 45.8±12.8 |

| FEV1.0, liters | 3.92±0.77* | 2.48±0.45 |

| FEV1.0, %predicted | 102.1±14.7 | 96.8±12.6 |

| FEV1.0/FVC | 78.4±3.4 | 78.0±4.5 |

| FVC, liters | 4.99±1.00* | 3.16±0.46 |

| Lung volume at CT scan, %predicted TLC | 72.7±10.3 | 75.4±12.0 |

| Lung volume at CT scan, ml | 6008±938* | 4549±692 |

| LAA% | 2.7±2.0 | 3.0±1.6 |

Values are means ± SD. BMI, body mass index; FEV1.0, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; TLC, total lung capacity; LAA%, percent low attenuation areas.

Significantly different from female (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of subjects matched for lung size

| Men (n = 10) | Women (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 69.2±2.2* | 67.0±1.8 |

| Height, cm | 175.6±5.7* | 170.1±4.6 |

| Weight, kg | 88.8±16.5* | 69.3±9.2 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.7±4.7* | 24.1±3.2 |

| Smoking, pack-yr | 54.6±22.7 | 42.7±13.2 |

| FEV1.0, liters | 3.13±0.22 | 2.98±0.31 |

| FEV1.0, %predicted | 88.4±9.0* | 107.4±9.2 |

| FEV1.0/FVC | 77.0±3.6 | 77.0±5.6 |

| FVC, liters | 4.08±0.20 | 3.88±0.35 |

| Lung volume at CT scan, ml | 5351±273 | 5116±922 |

| LAA% | 3.9±2.7 | 3.1±1.9 |

Values are means ± SD.

Significantly different from female (P < 0.05).

Airway area.

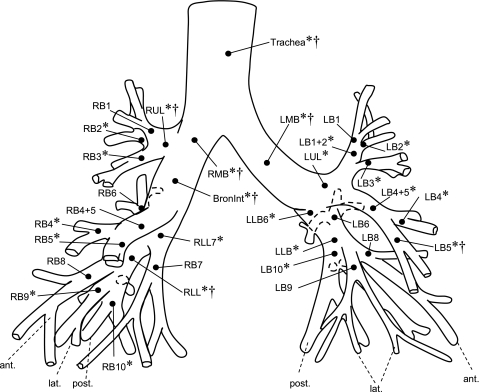

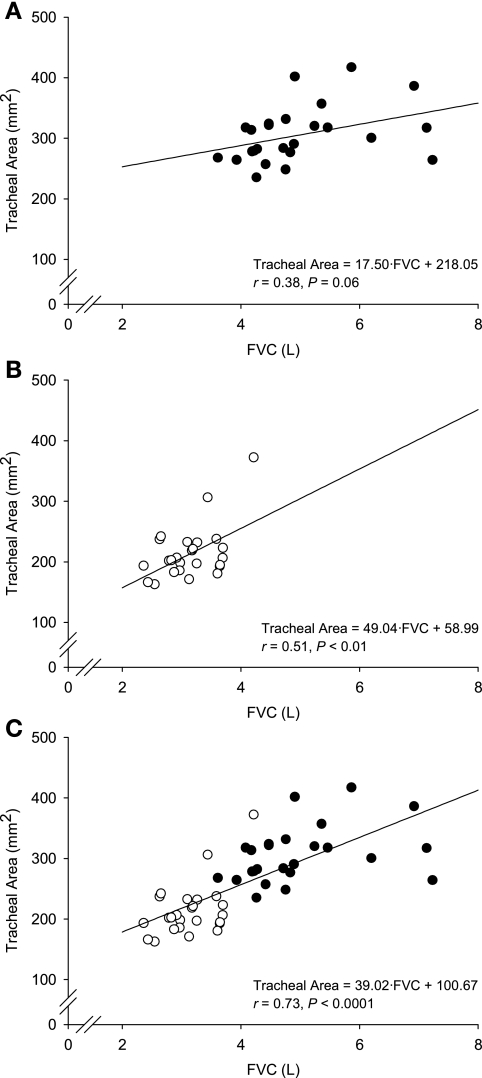

Figure 2 shows an airway tree diagram with assigned labels of airway segments. Significant differences were observed between men and women matched for age, BMI, smoking history, and %predicted values for spirometry. The mean values for Ai are shown in Table 3. These data show that men had significantly larger lumen areas compared with women for the larger central airways (trachea, generation 0 through lobar, generation 2) and many of the segmental (generation 3) airways. The association between tracheal lumen area and FVC, as an index of lung size, is shown in Fig. 3, while the remaining correlation coefficients for all the airways measured are summarized in Table 4. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.53 to 0.76 for the largest of the airways when male and female subjects were pooled together. However, within the male and female groups the magnitudes of these associations were decreased. The more distal airways had less (or no) association with lung size. There were significant associations between Ai and lung size (FVC) for some airways for men and women, but the strength of these relationships can be considered weak to modest. We performed correlational analyses using FVC as an index of lung size to facilitate comparisons with other investigations. We also performed these analyses using lung volume obtained during the CT scan. The relationships we observed were the same regardless of which measure of lung volume was used. Mean lung volumes during supine CT imaging are shown in Tables 1 and 2. These values were in excellent agreement with values obtained during pulmonary function testing, and no systematic changes due to posture were observed between men and women.

Fig. 2.

Airway tree with assigned labels. Labels refer to segments but are assigned to terminating branchpoint of respective segment. Drawing based on Boyden (3). post, posterior; lat, lateral; ant, anterior. *Significant differences between men and women of varying body size (P < 0.05). †Significant differences between subjects matched for lung size (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Airway luminal cross-sectional area (mm2) for subjects of varying body size

| Airway: | Men | Women | %Difference | Airway: | Men | Women | %Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trachea | 305.3±46.5 | 213.7±44.8 | 30.0* | RMB | 196.5±27.3 | 141.5±26.0 | 28.0* |

| LMB | 131.8±24.8 | 93.7±22.8 | 28.9* | RUL | 87.8±20.2 | 60.6±13.4 | 30.9* |

| LUL | 92.0±51.1 | 64.5±11.5 | 29.9* | RB1 | 28.1±13.2 | 23.1±13.9 | 17.7 |

| LB1 + 2 | 29.8±7.0 | 23.1±6.8 | 22.4* | RB2 | 26.9±8.6 | 19.9±6.2 | 26.2* |

| LB1 | 15.8±5.6 | 12.8±4.8 | 19.0* | RB3 | 31.7±10.0 | 24.9±7.4 | 21.5* |

| LB2 | 13.6±4.2 | 10.6±5.3 | 21.4* | BRONINT | 119.9±25.5 | 82.8±12.8 | 31.0* |

| LB3 | 31.8±12.7 | 24.6±7.7 | 22.9* | RB4 + 5 | 33.7±8.2 | 30.1±7.5 | 10.8 |

| LB4 + 5 | 39.9±13.3 | 26.9±6.5 | 32.5* | RB4 | 15.8±4.5 | 13.3±3.3 | 15.9* |

| LB4 | 17.1±6.3 | 11.8±3.8 | 31.0* | RB5 | 21.5±6.6 | 17.3±6.5 | 19.3* |

| LB5 | 17.0±5.2 | 11.4±3.6 | 33.0* | RLL | 40.2±10.8 | 38.5±15.2 | 4.1 |

| LLB6 | 80.2±20.3 | 67.8±22.6 | 15.5* | RLL7 | 61.7±19.3 | 49.8±15.7 | 19.2* |

| LLB | 49.2±14.9 | 40.0±7.7 | 18.8* | RB6 | 27.6±9.1 | 31.5±20.8 | −14.1 |

| LB6 | 31.3±9.2 | 26.6±8.6 | 14.9 (P = 0.08) | RB7 | 23.2±19.7 | 15.2±4.8 | 34.5 (P = 0.06) |

| LB8 | 25.1±10.1 | 21.8±5.0 | 13.2 | RB8 | 19.6±5.4 | 18.0±5.8 | 8.4 |

| LB9 | 21.6±6.1 | 20.4±14.2 | 5.7 | RB9 | 20.3±6.3 | 15.5±4.3 | 23.4* |

| LB10 | 24.8±5.8 | 20.9±4.5 | 15.8* | RB10 | 24.8±7.9 | 18.4±5.0 | 25.6* |

Values are means ± SD. LMB, left main bronchus; LUL, left upper lobe; LB, left bronchus; LLB, left lower lobe; RMB, right main bronchus; RUL, right upper lobe; RB, right bronchus; BRONINT, intermediate bronchus; RLL, right lower lobe.

Significant difference between men and women (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Tracheal area vs. forced vital capacity (FVC) in men (A), women (B), and with all subjects pooled together (C). Men are shown in solid circles and women in open circles.

Table 4.

Relationship between airway luminal cross-sectional area and forced vital capacity for subjects of varying body size

| Airway: | All Subjects | Men | Women | Airway: | All Subjects | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trachea | r = 0.73* | 0.38 | 0.51* | RMB | r = 0.76* | 0.48* | 0.49* |

| LMB | r = 0.67* | 0.30 | 0.59* | RUL | r = 0.64* | 0.34 | 0.26 |

| LUL | r = 0.53* | 0.43* | 0.44* | RB1 | r = 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.35 |

| LB1 + 2 | r = 0.57* | 0.33 | 0.54* | RB2 | r = 0.42* | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| LB1 | r = 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.05 | RB3 | r = 0.51* | 0.47* | 0.16 |

| LB2 | r = 0.28 | −0.06 | 0.32 | BRONINT | r = 0.66* | 0.27 | 0.42* |

| LB3 | r = 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.63* | RB4 + 5 | r = 0.36* | 0.22 | 0.52* |

| LB4 + 5 | r = 0.59* | 0.46* | −0.29 | RB4 | r = 0.50* | 0.45* | 0.38 |

| LB4 | r = 0.39* | 0.06 | 0.03 | RB5 | r = 0.50* | 0.47* | 0.47* |

| LB5 | r = 0.66* | 0.65* | −0.16 | RLL | r = 0.36* | 0.44* | 0.73* |

| LLB6 | r = 0.39* | 0.31 | 0.32 | RLL7 | r = 0.24 | −0.21 | 0.47* |

| LLB | r = 0.51* | 0.33 | 0.57* | RB6 | r = −0.02 | 0.28 | 0.01 |

| LB6 | r = 0.45* | 0.42* | 0.48* | RB7 | r = 0.45* | 0.40 | 0.30 |

| LB8 | r = 0.24 | 0.25 | −0.38 | RB8 | r = 0.29* | 0.26 | 0.34 |

| LB9 | r = 0.24 | 0.57* | 0.21 | RB9 | r = 0.48* | 0.33 | 0.17 |

| LB10 | r = 0.46* | 0.27 | 0.48* | RB10 | r = 0.46* | 0.18 | 0.34 |

Values are means ± SD.

Significant correlation (P < 0.05).

Also indicated in Fig. 3 are the specific airway comparisons between men and women matched for lung size. The mean values for Ai are shown in Table 5. These data show that women had significantly smaller lumen areas than men in only the largest airways (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

Airway luminal cross-sectional area (mm2) of subjects matched for lung size

| Airway: | Men | Women | %Difference | Airway: | Men | Women | %Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trachea | 296.1±44.2 | 238.3±58.1 | 19.5* | RMB | 193.2±28.1 | 147.3±26.7 | 23.8* |

| LMB | 124.7±22.7 | 102.1±27.8 | 18.1* | RUL | 76.6±18.3 | 65.3±8.7 | 14.75* |

| LUL | 79.4±18.1 | 71.4±14.2 | 10.1 | RB1 | 24.9±11.3 | 29.2±18.4 | −17.3 |

| LB1 + 2 | 19.2±13.7 | 21.3±13.1 | −10.9 | RB2 | 24.9±6.6 | 21.5±6.7 | 13.65 |

| LB1 | 14.2±5.8 | 13.6±3.5 | 4.2 | RB3 | 21.4±12.3 | 18.7±13.2 | 12.6 |

| LB2 | 14.4±5.2 | 13.4±5.3 | 6.9 | BRONINT | 115.6±14.0 | 86.2±12.0 | 25.4* |

| LB3 | 34.3±19.1 | 33.1±19.5 | 3.5 | RB4 + 5 | 34.5±9.2 | 33.3±5.7 | 3.5 |

| LB4 + 5 | 35.7±13.0 | 29.3±7.9 | 17.9 | RB4 | 15.3±4.0 | 15.0±3.9 | 2.0 |

| LB4 | 16.9±7.5 | 13.0±5.2 | 23.1 | RB5 | 22.0±6.5 | 21.4±7.3 | 2.7 |

| LB5 | 16.6±4.9 | 11.4±4.2 | 31.3* | RLL | 36.2±9.7 | 35.0±13.1 | 3.3 |

| LLB6 | 73.1±19.4 | 71.4±22.9 | 2.3 | RLL7 | 59.7±18.6 | 57.8±13.0 | 3.2 |

| LLB | 44.7±9.4 | 46.0±12.2 | −2.9 | RB6 | 24.0±11.1 | 27.8±7.2 | −15.8 |

| LB6 | 29.8±8.7 | 29.9±9.8 | −10.0 | RB7 | 18.9±4.6 | 16.7±3.4 | 11.6 |

| LB8 | 25.7±13.9 | 21.3±4.4 | 17.1 | RB8 | 18.9±5.6 | 20.1±7.1 | −6.4 |

| LB9 | 18.1±5.8 | 17.7±4.1 | 2.2 | RB9 | 18.2±5.7 | 17.1±2.6 | 6.0 |

| LB10 | 24.9±5.3 | 22.9±4.4 | 8.0 | RB10 | 21.8±7.5 | 21.1±5.9 | 3.2 |

Values are means ± SD.

Significant difference between men and women (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study we used CT scans of the lungs of men and women to determine if there were differences in the airway size between the sexes. The most important finding of this study is that there are significant male-female differences in the luminal areas of the larger and central airways (trachea generation 0 through lobar generation 2 and many of the segmental airways) that are not accounted for by differences in lung size. When matched for lung size, men and women have similar luminal areas of the more distal airways. Our collective findings provide new evidence for sex-based dysanapsis.

Our findings build on previous studies in several important ways. There have been very few published values for Ai beyond the trachea, and even fewer providing a direct comparison in lumen area between men and women. Those studies that have sought to directly compare airways between the sexes have principally used acoustic reflectance. Acoustic reflectance permits assessment only of the trachea rather than any of the other airways (4, 5, 7, 21, 23). In addition, acoustic reflectance estimates are made of a tracheal “region” rather than a single anatomic point. With the advancement of high-resolution CT scanning methods we have been able to overcome these limitations and appreciably expand on earlier observations and demonstrate the Ai of the larger and central airways are significantly smaller in women compared with men even when matched for lung volume.

Correlational analyses showed that there were statistically significant but moderate associations between lung size and Ai for the trachea and for the largest airways when male and female subjects were pooled together. However, when subjects were partitioned into separate groups the strength of these associations was reduced or was nonsignificant. We interpret these observations to mean that there is a modest-to-weak relationship between airways and lung parenchymal size. Collectively, our findings are in agreement with the concept of airway-parenchymal dysanapsis (19, 27). Our experimental approach does not provide insight into the potential mechanism(s) of dysanapsis, but there is evidence that there are sex differences in the maturation and physiological function of the lungs in early childhood that persist throughout adolescence and into adulthood (for review see, see Ref. 2).

We compared men and women with overlapping lung volumes to remove the effect of size per se and determine the relationship between airway size and lung parenchyma size. The larger airways were significantly larger in men relative to lung volume-matched women. The magnitude of difference (14–25%) we observed is consistent with previous reports that have shown that the tracheal areas of males are significantly larger than those of females after controlling for lung size (23). Our results confirm those previous findings and further extend their observations by showing that some, but not all, of the airways distal to the trachea are still smaller in women who have the same sized lungs as men. These are important observations if we consider the principles of airflow. Flow through the airway tree depends on the driving pressure and airway resistance. Airway resistance to airflow is affected by several factors: viscosity of the gas, length of the airway, gas density, and radius of the airway. Whether airflow is laminar or turbulent it is strongly dependent on the radius of a given airway as resistance to flow is inversely proportional to airway radius to the fourth power. This relationship, also called Poiseuille's equation, emphasizes that the radius of the airway is the major determinant of airway resistance when airflow is laminar and is typical in airways < 2 mm. In most of the bronchial tree airflow is either transitional or turbulent and is also dependent on the Reynolds number (Re) and is given by:

where d is density, v is average velocity, r is radius, and n is viscosity. Turbulence is most likely to occur when flow is high and airway diameter is relatively large. Importantly, when turbulent airflow occurs, the driving pressure is not proportional to flow and for a given flow the driving pressure must be much greater than that in laminar flow. As described by West (33), turbulence and the Re are higher in the trachea and other larger airways especially during conditions when airflow velocities are high. The main sites of airway resistance (∼80%) are the larger airways (up to 7th generation) whereas the smaller (<2 mm) airways contribute <20%. Within this context of the findings of the present study and the principles that govern airflow, we would predict that a woman with the same sized lungs as a man would have higher airway resistance and more turbulent airflow. This may be important under physiological conditions where ventilation is high such as dynamic exercise.

The findings of this study yield important insight into sex-based differences in pulmonary structure. The purpose of this study was not to relate airway dimensions to lung function under physiological or pathological conditions, but our observations do merit brief comment. For example, how might smaller airway areas influence the integrated pulmonary response to dynamic exercise? We postulate that smaller airway areas may be related to increased sensations of breathlessness, expiratory flow limitation, and higher work of breathing in women. Indeed these have all been reported in women and may negatively influence exercise capacity. This argument is supported by three separate sets of evidence. First, ratings of breathlessness and exercise intolerance are more pronounced in women with pulmonary disease (10, 22). This also appears to be the case in healthy older women (60–80 yr) (28). It is well known that ratings of breathlessness are multifactorial but may be related to mechanical constraints or a high work of breathing, among others. Second, there is now sufficient reason to suggest that healthy young women develop significant expiratory flow limitation during dynamic whole body exercise because of their smaller lungs and lower maximal expiratory flow rates, and therefore they may have a higher propensity for developing expiratory flow limitation compared with men (16, 25). Last, with increasing exercise intensity the work of breathing in women significantly increases out of proportion to men (15, 16). A high work of breathing is associated with significant neural and cardiovascular consequences (17, 30, 31) that can limit the ability to perform dynamic exercise (1, 29). Our observations were obtained in ex-smokers undergoing CT scans for clinical diagnostic purposes, and no measures of exercise capacity were made. As such, we are cognizant that the generalizability of our findings is narrow. However, our anatomic observations support the growing list of physiological evidence that points to a female pulmonary system that may be at mechanical disadvantage compared with their male counterparts during exercise.

To this point we have emphasized the differences in airway structure between men and women. It is important to note that many of the airways were indeed similar between men and women matched for lung size (see Table 5). The largest and most central airways were smaller in women, but the more distal airways were not different between men and women. Why would the more distal airways be similar between men and women with the most proximal airways being smaller in women? Moreover, do these similarities in the more distal airways somehow compensate for the differences we observed in the larger airways? Our cross-sectional approach does not provide an explanation for this apparent dissociation, and our observations may be complicated by both genetic and exogenous factors such as prolonged exposure to tobacco smoke or neonatal passive exposure. It is possible that the measurements of the more distal airways have less precision due to the resolution of the CT scanner than do the measurements of the central airways. However, while this size-dependent measurement bias could explain the similarities in the more distally measured airways, we view this as an unlikely explanation (see below).

Methodological considerations.

Several aspects of our methodology and subject characteristics should be considered when interpreting our findings. A limitation of this study is that it was not originally designed to study airways in normal subjects. Rather our study was part of a lung cancer-screening cohort. Since the subjects in this study were all middle-aged or older former smokers, we emphasize that caution should be given when comparing our results with those from other subject groups or healthy individuals. Also, extensive remodeling of the small peripheral airways is commonly seen in smokers, particularly those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (20), and it is thought that there are sex difference in the extent of this remodeling (24). However, our data focused on relatively “large, central” airways, not the small peripheral airways that cause the airflow limitation in COPD. Furthermore, our study population presented with normal spirometry measurements, and thus most of them were less likely to have COPD. Therefore, we think it is unlikely that the large differences in Ai between men and women observed in the present study can be wholly explained by airway remodeling induced by COPD, or by the sex differences in this airway remodeling. However, further investigations in healthy nonsmokers are needed in this area.

In smokers, luminal area measurements can be influenced by the degree of emphysema, and the effect of tobacco on lung parenchyma and airways could contribute to the difference observed between men and women. In this study we found no difference in the degree of emphysema between groups (see Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, recent findings show that at all levels of disease severity, current and former male smokers with COPD have more extensive CT emphysema than women (6, 11) although this remains controversial. As an explanation for our findings, it possible that the female lungs in the present study had lower recoil and required less distending pressure to reach TLC, and therefore a less (negative) pressure acting on the airways outside of the lung. This would result in less expansion and smaller cross-sectional area. Our experimental design does not provide a direct avenue of discounting this as a possibility.

Last, it is possible that the measurements we have obtained have been influenced by artifacts within both the CT image acquisition/reconstruction technique and the measurement technique. However, studies that have compared airways measured using CT to the same measurements obtained using histology have consistently shown that while CT underestimates lumen area, this error is systematic and greatest in airways <3 mm in diameter. The airways measured in our study were all above this range (4–20 mm diameter), and therefore we stand by our primary conclusion that the difference in Ai between men and women is an anatomically based phenomenon.

Summary.

We used computed tomography to measure airway luminal areas of the large and central airways in men and women using two approaches. We determined the relationship between lung size and airway size in men and women of varying stature and found that the airway luminal areas of the larger and central airways of women are smaller compared with those of men. We removed the effect of biological sex by matching men and women for lung size and found that women continue to have smaller airway luminal areas of the large airways below the tracheal carina. There are previous reports of significant male-female differences in tracheal size that are not accounted for by lung size. However, there are no studies that have determined if these differences exist beyond the trachea. This is the first study to address this question, and our findings provide an important advancement in our understanding of sex-based differences in airway geometry. We conclude that the larger and central airways in females are significantly smaller than those of males even after controlling for lung size.

GRANTS

This work was partially supported by National Cancer Institute Grants N01-CN-85188, 1U01-CA-96109, and P01-96964 (S. Lam). A. W. Sheel was supported by a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) and a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). A. W. Sheel is also supported, in part, by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). J. A. Guenette was supported by graduate scholarships from NSERC, MSFHR, and the Sir James Lougheed Award of Distinction. H. O. Coxson is a CIHR/British Columbia Lung Association New Investigator. H. O. Coxson is also supported, in part, by the Univ. of Pittsburgh COPD SCCOR NIH 1P50-HL-084948 and R01-HL-085096 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to the Univ. of Pittsburgh.

REFERENCES

- 1. Babcock MA, Pegelow DF, Harms CA, Dempsey JA. Effects of respiratory muscle unloading on exercise-induced diaphragm fatigue. J Appl Physiol 93: 201–206, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Becklake MR, Kauffmann F. Gender differences in airway behaviour over the human life span. Thorax 54: 1119–1138, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyden EA. Segmental Anatomy of the Lungs. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brooks LJ, Byard PJ, Helms RC, Fouke JM, Strohl KP. Relationship between lung volume and tracheal area as assessed by acoustic reflection. J Appl Physiol 64: 1050–1054, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown IG, Zamel N, Hoffstein V. Pharyngeal cross-sectional area in normal men and women. J Appl Physiol 61: 890–895, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Camp PG, Coxson HO, Levy RD, Pillai S, Anderson W, Vestbo J, Kennedy SM, Silverman EK, Lomas DA, Pare PD. Sex differences in emphysema and airway disease in smokers. Chest. Epub 17 July 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins DV, Cutillo AG, Armstrong JD, Crapo RO, Kanner RE, Tocino I, Renzetti AD., Jr Large airway size, lung size, and maximal expiratory flow in healthy nonsmokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 134: 951–955, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coxson HO, Quiney B, Sin DD, Xing L, McWilliams AM, Mayo JR, Lam S. Airway wall thickness assessed using computed tomography and optical coherence tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177: 1201–1206, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crapo RO, Morris AH, Gardner RM. Reference spirometric values using techniques and equipment that meet ATS recommendations. Am Rev Respir Dis 123: 659–664, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Torres JP, Casanova C, Hernandez C, Abreu J, Aguirre-Jaime A, Celli BR. Gender and COPD in patients attending a pulmonary clinic. Chest 128: 2012–2016, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dransfield MT, Washko GR, Foreman MG, Estepar RS, Reilly J, Bailey WC. Gender differences in the severity of CT emphysema in COPD. Chest 132: 464–470, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Green M, Mead J, Turner JM. Variability of maximum expiratory flow-volume curves. J Appl Physiol 37: 67–74, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Griscom NT, Wohl ME. Dimensions of the growing trachea related to age and gender. AJR Am J Roentgenol 146: 233–237, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Griscom NT, Wohl ME. Dimensions of the growing trachea related to body height. Length, anteroposterior and transverse diameters, cross-sectional area, and volume in subjects younger than 20 years of age. Am Rev Respir Dis 131: 840–844, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guenette JA, Querido JS, Eves ND, Chua R, Sheel AW. Sex differences in the resistive and elastic work of breathing during exercise in endurance-trained athletes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R166–R175, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guenette JA, Witt JD, McKenzie DC, Road JD, Sheel AW. Respiratory mechanics during exercise in endurance-trained men and women. J Physiol 581: 1309–1322, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harms CA, Babcock MA, McClaran SR, Pegelow DF, Nickele GA, Nelson WB, Dempsey JA. Respiratory muscle work compromises leg blood flow during maximal exercise. J Appl Physiol 82: 1573–1583, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hlastala MP, Berger AJ. Physiology of Respiration. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoffstein V. Relationship between lung volume, maximal expiratory flow, forced expiratory volume in one second, and tracheal area in normal men and women. Am Rev Respir Dis 134: 956–961, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hogg JC, Macklem PT, Thurlbeck WM. Site and nature of airway obstruction in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med 278: 1355–1360, 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang J, Shen H, Takahashi M, Fukunaga T, Toga H, Takahashi K, Ohya N. Pharyngeal cross-sectional area and pharyngeal compliance in normal males and females. Respiration 65: 458–468, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katsura H, Yamada K, Wakabayashi R, Kida K. Gender-associated differences in dyspnoea and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology 12: 427–432, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin TR, Castile RG, Fredberg JJ, Wohl ME, Mead J. Airway size is related to sex but not lung size in normal adults. J Appl Physiol 63: 2042–2047, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, Sciurba F, Mumford J, Giardino ND, Weinmann G, Kazerooni E, Murray S, Criner GJ, Sin DD, Hogg J, Ries AL, Han M, Fishman AP, Make B, Hoffman EA, Mohsenifar Z, Wise R. Sex differences in severe pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 243–252, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McClaran SR, Harms CA, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Smaller lungs in women affect exercise hyperpnea. J Appl Physiol 84: 1872–1881, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McWilliams A, Mayo J, MacDonald S, leRiche JC, Palcic B, Szabo E, Lam S. Lung cancer screening: a different paradigm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 1167–1173, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mead J. Dysanapsis in normal lungs assessed by the relationship between maximal flow, static recoil, and vital capacity. Am Rev Respir Dis 121: 339–342, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ofir D, Laveneziana P, Webb KA, Lam YM, O'Donnell DE. Sex differences in the perceived intensity of breathlessness during exercise with advancing age. J Appl Physiol 104: 1583–1593, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Romer LM, Lovering AT, Haverkamp HC, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Effect of inspiratory muscle work on peripheral fatigue of locomotor muscles in healthy humans. J Physiol 571: 425–439, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sheel AW, Derchak PA, Morgan BJ, Pegelow DF, Jacques AJ, Dempsey JA. Fatiguing inspiratory muscle work causes reflex reduction in resting leg blood flow in humans. J Physiol 537: 277–289, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. St Croix CM, Morgan BJ, Wetter TJ, Dempsey JA. Fatiguing inspiratory muscle work causes reflex sympathetic activation in humans. J Physiol 529: 493–504, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tschirren J, Hoffman EA, McLennan G, Sonka M. Intrathoracic airway trees: segmentation and airway morphology analysis from low-dose CT scans. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 24: 1529–1539, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. West JB. Respiratory Physiology—the Essentials. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2008. [Google Scholar]