Abstract

Translational pausing can lead to cleavage of the A-site codon and facilitate recruitment of the tmRNA (SsrA) quality control system to distressed ribosomes. We asked whether A-site mRNA cleavage occurs during regulatory translational pausing using the Escherichia coli SecM-mediated ribosome arrest as a model. We find the SecM ribosome arrest does not elicit efficient A-site cleavage, but instead allows degradation of downstream mRNA to the 3 ´ edge of the arrested ribosome . Characterization of SecM-arrested ribosomes shows the nascent peptide is covalently linked via glycine-165 to tRNA3 Gly in the P site, and prolyl-tRNA2 Pro is bound to the A site. Although A-site cleaved mRNAs were not detected, tmRNA-mediated ssrA-tagging after SecM glycine-165 was observed. This tmRNA activity results from sequestration of prolyl-tRNA2Pro on over-expressed SecM-arrested ribosomes, which produces a second population of stalled ribosomes with unoccupied A sites. Indeed, compensatory over-expression of tRNA2 Pro readily inhibits ssrA-tagging after glycine-165, but has no effect on the duration of SecM ribosome arrest. We conclude that, under physiological conditions, the architecture of SecM-arrested ribosomes allows regulated translational pausing without interference from A-site cleavage or tmRNA activities. Moreover, it seems likely that A-site mRNA cleavage is generally avoided or inhibited during regulated ribosome pauses.

A-site1 mRNA cleavage is a novel RNase activity that acts on A-site codons within paused ribosomes. Ehrenberg, Gerdes and their colleagues first demonstrated that Escherichia coli RelE protein causes cleavage of A-site mRNA in vitro (1). Subsequently, A-site cleavage was also shown to occur at stop codons during inefficient translation termination in cells that lack RelE and related proteins (2,3). The latter finding indicates that another unknown A-site nuclease also exists in E. coli. Indeed, it is possible the ribosome itself catalyzes A-site cleavage. The molecular requirements for A-site cleavage are incompletely understood, but an unoccupied ribosome A site appears to be important for both RelE-dependent and RelE-independent nuclease activity (1,2).

A-site nuclease activity truncates mRNAs and produces stalled ribosomes that are unable to continue standard translation. In bacteria, ribosomes stalled at the 3´ termini of such truncated messages are “rescued” by the tmRNA quality control system. tmRNA is a specialized RNA that acts first as a tRNA to bind the A site of stalled ribosomes, and then as an mRNA to direct the addition of the ssrA peptide degradation tag to the C terminus of the nascent polypeptide (4,5). As a result of tmRNA activity, incompletely synthesized proteins are targeted for proteolysis and stalled ribosomes undergo normal translation termination and recycling (5). In this manner, A-site mRNA cleavage and tmRNA work together as a translational quality control system that responds to paused and stalled ribosomes.

Although a paused ribosome can be a manifestation of translational difficulty, translational pausing is also used to control and regulate protein synthesis. In many instances, the newly synthesized nascent peptide inhibits either translation elongation or termination (6,7). A recently described example is the SecM-mediated ribosome arrest, which controls expression of SecA protein from the secM-secA mRNA in E. coli (8). The SecM nascent peptide interacts with the ribosome exit channel to elicit a site-specific ribosome arrest (9). The SecM-stalled ribosome is postulated to disrupt a downstream mRNA secondary structure that sequesters the secA ribosome binding site (9,10). Thus, efficient initiation of secA translation depends upon ribosome pausing at the upstream secM open reading frame (11). SecM-mediated ribosome pausing is regulated in turn by the activity of SecA protein. SecM is secreted co-translationally by the general Sec machinery, which is powered in part by the SecA ATPase (12). It is thought that the mechanical pulling force exerted by SecA on the SecM nascent chain during secretion alleviates the ribosome arrest and allows translation to continue (13,14). This intriguing regulatory circuit allows the cell to monitor protein secretion activity via ribosome pausing and adjust SecA synthesis accordingly.

One outstanding question is how A-site cleavage and tmRNA activities affect regulatory translational pauses such as the SecM-mediated ribosome arrest. If all paused ribosomes are subject to A-site cleavage, then this nuclease activity would be expected to interfere with SecA regulation. The experiments presented in this paper demonstrate that A-site mRNA cleavage and the tmRNA quality control system do not significantly affect SecM-mediated ribosome arrest. Two recent reports have demonstrated that the A site of SecM-arrested ribosomes is filled with tRNA (15,16). The cryo-EM structure from Frank and colleagues shows that ~40% of SecM-arrested ribosomes contain a fully accommodated A-site tRNA (15). Ito and colleagues have recently analyzed SecM-arrested ribosomes prepared by in vitro translation and concluded that the A-site tRNA is a prolyl-tRNAPro (16). In our analysis of SecM-arrested ribosomes in vivo, we also find that the P and A sites of the SecM-arrested ribosome are occupied with peptidyl- and aminoacyl-tRNAs, respectively. Additionally, we show that the occupied A site prevents tmRNA recruitment during ribosome arrest and may also inhibit A-site mRNA cleavage. Thus, regulation by SecM ribosome arrest is able to operate efficiently in the presence of quality control systems that alleviate ribosome stalling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

Table I lists the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study. All bacterial strains were derivatives of E. coli strain X90 (17). Strain CH12 [X90 (DE3)] was generated using the Novagen (DE3) λ lysogen kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. Strain CH2198 [X90 ssrA(his6) (DE3)] was obtained by introducing the ssrA(His6) allele (18) of tmRNA into the ssrA chromosomal locus using the phage λ Red recombination method with minor modifications (17,19). The same method was used to delete the rna (encoding RNase I), rnb (encoding RNase II) and pnp (encoding PNPase) genes. The rnr∷kan disruption and the strain expressing truncated RNase E have been described previously (2,20). All gene disruptions and deletions were introduced into strain CH113 by phage P1-mediated transduction. The kanamycin resistance cassette was removed from strain CH113 Δrnb∷kan using FLP recombinase as described (19), allowing construction of the Δrnb rnr∷kan double mutant. Lac− strains of X90 and X90 ssrA∷cat were obtained by curing the strain of the F´ episome as described (17). The details of all strain constructions are available upon request.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| X90 | F´ lacIq lac´ pro´/ara Δ[lac-pro] nalA argE[am] rifr thi-1 | (17) |

| CH1924 | X90 F− | This study |

| CH1925 | X90 F− ssrA∷cat, Cmr | This study |

| CH113 | X90 ssrA∷cat (DE3), Cmr | This study |

| CH12 | X90 (DE3) | This study |

| CH2198 | X90 ssrA(his6) (DE3), Kanr | This study |

| CH988 | CH113 rnr∷kan, Cmr , Kanr | (20) |

| CH1002 | CH113 rne515∷kan, Cmr , Kanr | (2) |

| CH1207 | CH113 Δrnb∷kan, Cmr , Kanr | This study |

| CH1208 | CH113 Δpnp∷kan, Cmr , Kanr | This study |

| CH1227 | CH113 Δrnb rnr∷kan, Cmr,Kanr | This study |

| CH1915 | CH12 Δrna∷kan,Kanr | This study |

| CH1916 | CH113 Δrna∷kan, Cmr, Kanr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pFG21b | derivative of pET21b with FLAG epitope-encoding sequence, Ampr |

This study |

| pSecMA´ | pFG21b∷secMA´, Amprr | This study |

| p(Δss)SecMA´ | pFG21b∷(Δss)secMA´, Ampr | This study |

| p(Δss-P166A)SecMA´ | pFG21b∷(Δss-P166A)secMA´, Ampr | This study |

| pTrx-SecM´-Trx | pFG21b∷trxA-secM´-trxA, Ampr | This study |

| pSecM´ | pFG21b∷secM´, Ampr | This study |

| pTrc3 | derivative of pTrc99a containing 5´ NdeI restriction site, Ampr | This study |

| pSecMA´-LacZ | pTrc3∷secMA´∷lacZ, Ampr | This study |

| p(Δss)SecMA´-LacZ | pTrc3∷(Δss)secMA´∷lacZ, Ampr | This study |

| p(Δss-P166A) SecMA´-LacZ |

pTrc3∷(Δss-P166A)secMA´∷lacZ, Ampr | This study |

| pCH405Δ | derivative of pACYC containing multi-cloning site, Tetr | (2) |

| ptRNA2Pro | pCH405Δ∷proL, over-expresses tRNA2 Pro, Tetr | This study |

Plasmid pFG21b is a modified version of plasmid pET21d (Novagen), which encodes a FLAG peptide epitope between NcoI and NdeI restriction sites. Plasmid pFG21b allows the production of N-terminal FLAG-tagged proteins, provided the initiation Met codon is engineered into an NdeI restriction site. All expression plasmids were derived from plasmid pFG21b, with the exception of the LacZ translational fusions, which were constructed using a derivative of pTrc99a (Pharmacia). Fragments containing secMA´ were obtained by PCR using oligonucleotide primers containing restriction endonuclease sites (underlined residues). The secMA´ fragment was amplified from E. coli genomic DNA with oligonucleotides secM-Nde (5´- GGA TGG CAA TCA TAT GAG TGG AAT ACT GAC GCG CTG G), and secA-Bam (5´-CCG GGA TCC GAT TTT CCA GCA CTT CGC C ) . The (Δ ss)secMA´ fragment was generated with the secA-Bam primer and secM-A38 (5´-CCT GCG CTC AGC CAT ATG GCC GAA CCA AAC GCG CCC GC). The PCR products were digested with NdeI and BamHI and ligated to plasmid pFG21b. The mutation changing SecM residue proline-166 to alanine was made using primer secM-P166A (5´ -CCG TGC TGG CGC TCA ACG CCT CAC C) in combination with primers secA-Bam and secM-A38 by the PCR megaprimer method (21). LacZ translational fusions were made in two steps: i) ligation of the various secMA´ NdeI/BamHI fragments into plasmid pTrc3 followed by, ii) ligation of a BamHI/HindIII fragment containing the E. coli lacZ gene. The lacZ fragment was produced by PCR using primers, lacZ-Bam (5´- AGG GAT CCA AAT GAT TAC GGA TTC ACT GGC CGT CG) and lacZ-Hind (5´- GGA TAA GCT TAC GCG AAA TAC GGG CAG ACA TGG C).

Plasmid pTrxA-SecM´-TrxA was constructed from pFG21b in three steps. Two distinct trxA-containing PCR products were generated: the first from primers trxA-Nde (5´- GTG GAG TTA CAT ATG AGC GAT AAA ATT ATT CAC C) and trxA-Bam (5´- AAA TGG ATC CCC GCC AGG TTA GCG TCG AGG AAC TC); and the second from primers trxA-Eco (5´- ATA GAA TTC CGA TAA AAT TCA CCT GAC TGA CGA C) and trxA-Xho (5´- GAA CTC GAG ATT CCC TTA CGC CAG GTT AGC GTC G). The two trxA PCR fragments were sequentially ligated into pFG21b using NdeI/BamHI and EcoRI/XhoI digestions to generate plasmid pTrx-Trx. The oligonucleotides ts´t-top (5´- GAT CCA ATT CAG CAC GCC CGT CTG GAT AAG CCA GGC GCA AGG CAT CCG TGC TGG CCC TCA G) and ts´t-bottom (5´- AAT TCT GAG GGC CAG CAC GGA TGC CTT GCG CCT GGC TTA TCC AGA CGG GCG TGC TGA ATT G) were annealed to one another and ligated to BamHI/EcoRI-digested plasmid pTrx-Trx to generate pTrx-SecM´-Trx. Similarly, pSecM´ was generated by annealing secM´-top (5´- TAT GCA ATT CAG CAC GCC GGT CTG GAT AAG CCA GGC GCA AGG AAT CCG TGC TGG CCC TCA AAA G) and secM´-bottom (5´- AAT TCT TTT GAG GGC CAG CAC GGA TTC CTT GCG CCT GGC TTA TCC AGA CCG GCG TGC TGA ATT GCA) followed by ligation to NdeI/EcoRI-digested pFG21b. The ptRNA2 Pro over-expression plasmid was constructed by amplifying the proL gene and its promoter with primers proL-Sac (5´- CTG GAG CTC AAC AAT AAC GGT AAA TAC C), and proL-Kpn (5´- AGC GGT ACC TTG TCA GTC AGC TAT GG) followed by ligation of the resulting PCR product into SacI/KpnI-digested plasmid pCH405Δ (2,17).

mRNA Expression and RNA Analysis

E. coli strains were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (150 µg/ml of ampicillin, 25 µg/ml of tetracycline, or 50 µg/ml of kanamycin). The next day, cells were resuspended at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 in 15 ml of fresh medium and grown at 37°C with aeration. Once cultures reached an OD600 of ~0.3, mRNA expression was induced with IPTG (1.5 mM). After further incubation for 30 min, 15 ml of ice-cold methanol was added to the cultures, the cells collected by centrifugation, and the cell pellets frozen at −80°C. Total RNA was extracted from cell pellets using 1.0 mL of a solution containing 0.6 M ammonium isothiocyanate – 2 M guanidinium isothiocyanate – 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.0) – 5% glycerol – 40% phenol. The disrupted cell suspension was extracted with 0.2 ml of chloroform, the aqueous phase removed and added to an equal volume of isopropanol to precipitate total RNA. RNA pellets were washed once with ice-cold 75% ethanol and dissolved in either 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) – 1 mM EDTA or 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2) – 1 mM EDTA.

Northern blot and S1 nuclease protection analyses of all mRNAs were performed as described (2). Northern blot analysis to identify the nascent peptidyl-tRNA species was performed using acid urea gels as described (22) with modifications. Total RNA (10 µg) was separated on 50% urea – 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2) – 1 mM EDTA – 6% polyacrylamide gels run at 4°C. Gels were briefly soaked in 0.5 × Tris-borate- EDTA (TBE) buffer before electroblotting (250 mA) to positively charged nylon membrane in 0.5 × TBE for 1 hour at 4 °C. All subsequent Northern hybridization conditions were as described (2). The following radiolabeled DNA oligonucleotide probes were used in hybridizations: proL for tRNA2 Pro (5´-CAC CCC ATG ACG GTG CG); proK for tRNA1 Pro (5´-CTT CGT CCC GAA CGA AGT G); glyV for tRNA3 Gly (5´- CTT GGC AAG GTC GTG CT); argQ for RNA2 Arg (5´- CCT CCG ACC GCT CGG TTC G); and RBS for pET-derived ribosome binding site (5´- GTA TAT CTC CTT CTT AAA GTT AAA C). The following radiolabeled DNA oligonucleotides were used as probes for S1 nuclease protection experiments: secM S1 probe (5´- TTA ATA AAA TGA AGT AAA GGT TTA TTG TTG TTA GGT GAG GCG TTG AGG GCC AGC ACG GAT GCC TTG CGC CTG GCT TAT CC); and secM´-trxA S1 probe (5´- CTG TCG TCA GTC AGG TGA ATT TTA TCG GAA TTC TGA GGG CCA GCA CGG ATG CCT TGC GCC TGG CTT ATC CAG).

SecM Expression and Protein Analysis

Strains were cultured as described above for RNA analysis. Protein extraction and Western blot analyses were conducted as described (17). Anti-His6 polyclonal antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biochemical. Monoclonal antibodies specific for E. coli β-galactosidase and the FLAG M2 epitope were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. SsrA(His6)-tagged SecM proteins were purified by Ni2+-NTA agarose (Qiagen) affinity chromatography as described (17,18). Ni2+-NTA purified protein was further purified by reverse phase-HPLC. N-terminal gas-phase sequencing was performed on a Porton 2020 protein sequencer (Beckman-Coulter) with a dedicated in-line HPLC (model 2090) for separation of phenylthiohydantoin derivatives. Molecular masses were determined by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Samples were applied to a Zorbax 300SB-C18 reverse phase column in aqueous 0.1% formic acid and proteins eluted using a linear gradient of acetonitrile using an Agilent 1100 LC nano-system. Eluted proteins were infused into a Waters Q-Tof II™ mass spectrometer for ionization.

β-Galactosidase assays were conducted essentially as described (23). Strains expressing secA´∷lacZ translational fusions were inoculated at OD600 of 0.05 in LB medium and grown at 37°C with aeration to OD600 of 0.3 – 0.6. β-Galactosidase activity for each construct was measured from 5 to 8 independent cultures and reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Cell Extract Fractionation

Strains CH12 Δ rna∷kan and CH113 Δ rna∷kan containing plasmid pSecM´ or pSecM´ (P166A) were grown in 1 liter of LB media at 37°C with aeration in Fernbach flasks. At OD600 ~ 0.6, SecM´ expression was induced by the addition of IPTG to 1.5 mM and cultures incubated for one hr at 37°C with aeration. Cultures were harvested over ice, the cells collected by centrifugation and washed once with cold, high-Mg2+ S30 buffer [60 mM potassium acetate – 30 mM magnesium acetate – 0.2 mM EDTA – 10 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.0)]. Washed bacterial pellets were resuspended in 10 mL of cold high-Mg2+ S30 buffer and the cells broken by one passage through a French press at 12,000 psi. Cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatants layered onto cushions of cold high-Mg2+ S30 buffer containing 1.1 M sucrose in ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman #344057). Samples were centrifuged in a Beckman-Coulter Optima™ ultracentrifuge at 45,000 rpm for one hr at 4°C using an MLS-50 rotor. Total RNA was extracted from the high-speed supernatants and pellets for analysis as described above.

RESULTS

SecM ribosome arrest leads to mRNA cleavage

To determine whether SecM-mediated ribosome arrest leads to A-site cleavage, we generated plasmids to express mRNA encoding SecM and the first 62 residues of SecA (Figure 1A). Three SecM variants were used throughout this work: i) Flag-SecM, which is the wild-type protein fused to a n N-terminal FLAG epitope tag; ii) Flag- (Δss)SecM, which lacks the secretion signal sequence (Δss = deleted signal sequence; residues 1 – 37); and iii) Flag-(Δss-P166A)SecM, which lacks the signal sequence and has alanine in place of proline-166. Deletion of the SecM signal sequence prevents its secretion and leads to a profound ribosome arrest, whereas the P166A variant completely abrogates arrest (9,14). The FLAG sequence was added to facilitate analysis of SecM proteins by Western blot. However, secretion of Flag-SecM protein resulted in the removal of the FLAG epitope along with the signal sequence (see below).

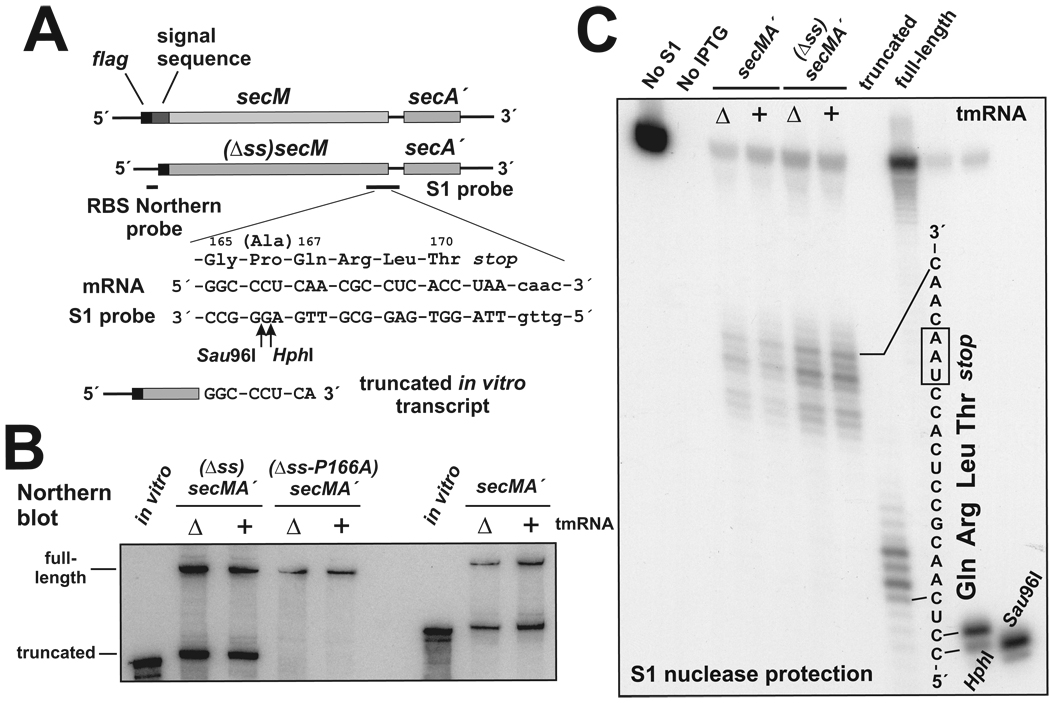

Figure 1. SecM ribosome arrest leads to mRNA cleavage.

(A) secMA´ mRNA variants are shown with the FLAG epitope, signal sequence and oligonucleotide probe binding sites indicated. SecM residues glycine-165 to threonine-170 and the encoding mRNA sequence are shown, as is the complementary sequence of the S1 nuclease probe and the 3´ terminus of the truncated in vitro transcripts used. The position of the P166A alteration is indicated by (Ala). Arrows indicate the positions of HphI and Sau96I restriction endonuclease cleavages in the S1 probe used to generate gel migration standards. (B) Northern blot of secMA´ mRNAs purified from tmRNA+ and ΔtmRNA cells. The positions of full-length and truncated flag-(Δss)secMA´ mRNA are indicated. Both in vitro transcripts were truncated after the second nucleotide of the glutamine-167 codon. (C) S1 nuclease protection map of truncated secMA´ mRNAs. Cleavages were detected in the secM stop codon and at positions one to four nucleotides downstream. No S1 protection was detected with RNA purified from a strain that had not been induced with IPTG. Truncated and full-length transcripts were produced by in vitro transcription and analyzed by S1 nuclease protection. The HphI and Sau96I oligonucleotide standards were generated by annealing the 3´-labeled S1 probe to a complementary DNA oligonucleotide followed by digestion with the appropriate endonucleases.

Each SecM protein was expressed in wild-type cells (tmRNA+) and cells that lack tmRNA (ΔtmRNA), and the corresponding messages examined by Northern blot analysis using a probe specific for the ribosome binding site upstream of secM. In addition to the full-length mRNAs, truncated flag-secMA´ and flag-(Δss)secMA´ messages were also detected (Figure 1B). The truncated mRNAs did not hybridize to a probe specific for downstream secA sequence (data not shown). No truncated flag-(Δss-P166A)secMA´ mRNA was apparent, suggesting that ribosome arrest was required for mRNA cleavage. Interestingly, steady state levels of truncated flag-secMA ´ and flag-(Δss)secMA´ mRNAs were similar in wild-type and ΔtmRNA cells (Figure 1B). This finding was noteworthy because tmRNA activity usually promotes rapid degradation of truncated mRNAs, including those produced by A-site mRNA cleavage (2,3,24). Moreover, the truncated mRNAs appeared to be somewhat larger than in vitro transcripts that terminate in the codon for glutamine-167, a position that is adjacent to the A site of the arrested ribosome (Figures 1A & B) (16).

The 3´ ends of the truncated messages were mapped more precisely using S1 nuclease protection analysis. The termini were somewhat heterogeneous but strong cleavage was detected inside and adjacent to the secM stop codon (Figure 1C). No cleavages were detected in the codon for glutamine-167, which would have produced an S1 protection pattern similar to that observed with the truncated control in vitro transcript (Figure 1C, truncated lane). As suggested by the Northern analysis described above, mRNA cleavage occurred approximately 13 to 19 nucleotides downstream of the predicted A-site codon during SecM ribosome arrest.

3´→5´ exonucleases generate truncated secM mRNA during ribosome arrest

Two models account for ribosome arrest-dependent cleavage at the secM stop codon: i) A-site cleavage due to inefficient translation termination as originally described in (2,3), or ii) exonucleolytic trimming of downstream mRNA to the 3´ margin of the arrested ribosome. To differentiate between these possibilities, we fused secM codons 150 – 166 in-frame between two thioredoxin genes (trxA). The encoded Flag-TrxA-SecM´-TrxA fusion protein contained the minimal SecM peptide motif (F150STPVWISQAQGIRAGP166) sufficient for ribosome arrest (9). However, in contrast to the wild-type secM gene, the flag-trxA-secM´-trxA stop codon is positioned several hundred nucleotides downstream of the predicted ribosome arrest site. (21)

Northern analysis of flag-trxA-secM´-trxA mRNA also showed ribosome arrest-dependent truncated messages (data not shown), and S1 nuclease protection analysis detected two prominent cleavage sites at 13 and 19 nucleotides downstream of the proline-166 codon (wild-type SecM numbering) (Figure 2B, wild-type lane). The cleavages were the same distance from the proline-166 codon as was observed with flag-secMA ´ and flag-(Δss)secMA´ mRNAs (Figure 2A and Figure 1C). Although the cleavage patterns were not strictly identical between truncated messages, the secM stop codon was clearly not required for mRNA cleavage.

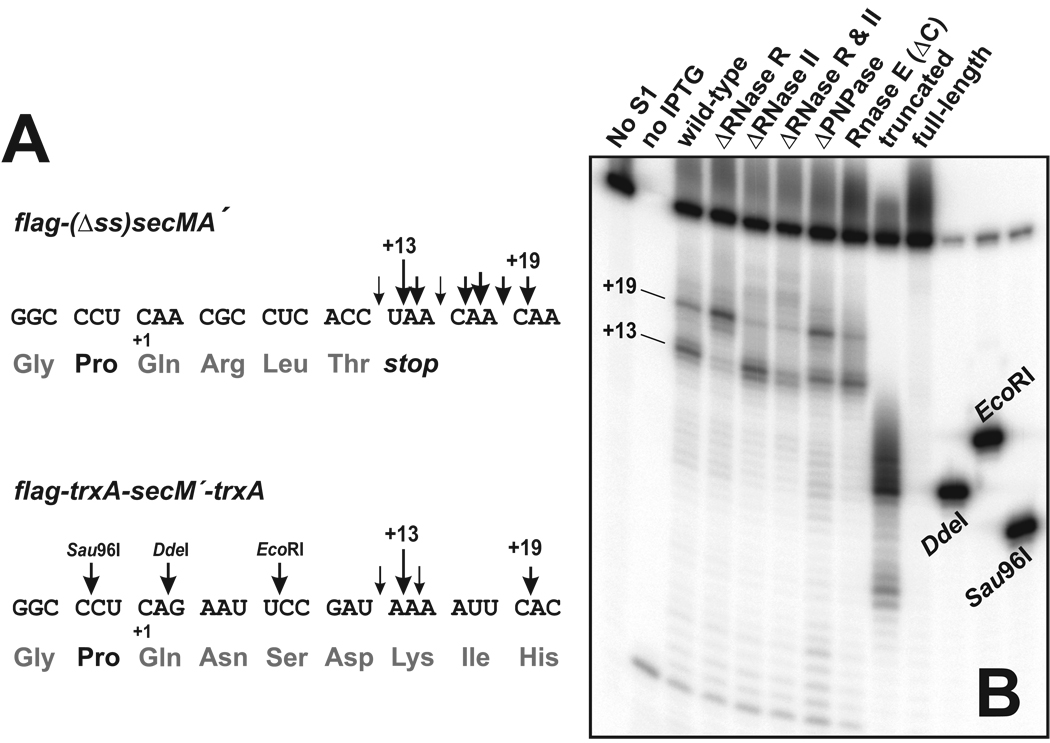

Figure 2. mRNA cleavage is modified in cells lacking 3´→5´ exoribonucleases.

(A) RNA sequences of flag-(Δss)secMA´ and flag-trxA-secM´-trxA messages near the observed cleavage sites are shown along with the encoded protein sequences. Downward arrows indicate the position and relative intensity of mRNA cleavage as determined by S1 nuclease protection analyses shown in panel B and Figure 1C. Numerical position is reported with respect to the codon corresponding to SecM proline-166, where position +1 is the first nucleotide of the codon corresponding to SecM glutamine-167. Downward arrows labeled DdeI, EcoRI and Sau96I indicate mRNA cleavage sites corresponding to the migration positions of S1 oligonucleotide probe standards. (B) S1 nuclease protection analysis of flag-trxA-secM´-trxA mRNA purified from cells lacking 3´→5´ exoribonucleases. Gene deletions and disruptions were constructed as described in Experimental Procedures. Positions +13 and +19 downstream of the codon corresponding to SecM proline-166 are indicated. The DdeI, EcoRI and Sau96I oligonucleotide standards were generated by annealing the labeled S1 probe to a complementary DNA oligonucleotide followed by digestion with the appropriate endonucleases.

We reasoned that if ribosome arrest-dependent mRNA cleavage was due to exonuclease activity, then cleavage could be modulated by deletion of known 3´→5´ exoribonucleases. Figure 2B shows the effects of specific exoribonuclease deletions on mRNA cleavage using the flag-trxA-secM´-trxA message. Deletion of RNase R lead to an increase in the +19 cleavage product and a decrease in the +13 cleavage product compared to wild-type (Figure 2B). Similarly, removing polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) activity also lead to increased levels of the +19 product (Figure 2B). In contrast, there was a slight decrease in the +19 product in ΔRNase II cells (Figure 2B). The RNase R/RNase II double deletion strain exhibited less cleavage at both sites, whereas deletion of the C-terminal domain of RNase E had little effect on cleavage (Figure 2B). Although RNase E is an endoribonuclease, the C-terminal domain is required for the organization of the degradosome, a multi-enzyme complex that contains PNPase and is important for the degradation of many mRNAs in E. coli (25,26). In general, the accumulation of specific cleavage products was dependent upon exoribonuclease activities.

The SecM nascent peptide is linked to tRNAGly during ribosome arrest

The accumulation of truncated secM messages in tmRNA+ cells and the involvement of exoribonucleases in mRNA cleavage are inconsistent with what is known about A-site cleavage. Moreover, the SecM-induced ribosome arrest occurs at the codon for proline-166 (9,16), a position that is 13 – 15 nucleotides upstream of the stop codon (Figure 1A). We sought to confirm the position of SecM-stalled ribosomes using a mini-gene that encodes SecM residues glutamine-149 to glutamine-167 directly downstream of the FLAG epitope. Additionally, the flag-secM´ mini-gene was synonymously recoded to change the codon for proline-153 from CCC to CCG, and the codon for glycine-161 from GGC to GGA.

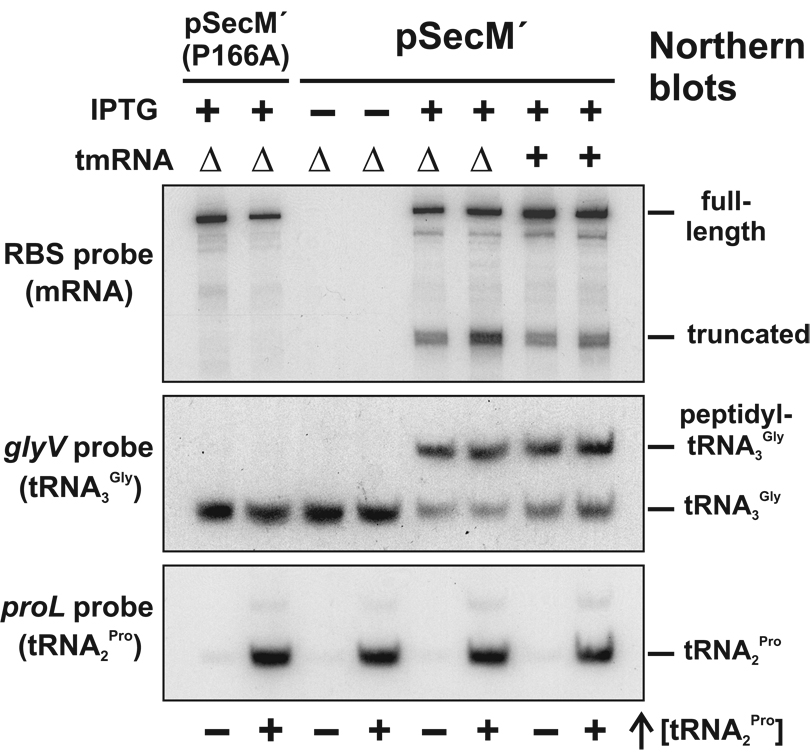

Northern analysis using a probe specific for the ribosome binding site of flag-secM´ detected truncated mRNA, and this cleavage appeared to depend upon ribosome stalling because truncated mRNA was not observed with the P166A variant (Figure 3, RBS probe blot). The position of the arrested ribosome was determined by identifying the nascent peptidyl-tRNA by Northern blot analysis. Induction of Flag-SecM´ synthesis led to a shift in the electrophoretic mobility of tRNA3 Gly but not that of tRNA2 Pro (Figure 3, glyV and proL probe blots). The tRNA3 Gly mobility shift was not observed when the Flag-(P166A)SecM´ variant was expressed (Figure 3, glyV probe blot). The tRNA3 Gly mobility shift was not seen when RNA samples were incubated at pH 8.9 for 1 hr at 37°C to deacylate tRNAs (data not shown) (22). The arrested ribosome could be positioned unambiguously because the recoded mini-gene contained only one codon (GGC of glycine-165) that is decoded by tRNA3 Gly. Therefore, during SecM-mediated ribosome arrest, the nascent peptide is covalently linked to tRNA3 Gly via glycine-165 and the codon for proline-166 is positioned in the A site.

Figure 3. The SecM nascent peptide is covalently linked to tRNA3 Gly.

RNA from strains expressing flag-secM´ [pSecM´] and flag-(P166A)secM´ [pSecM´ (P166A)] mini-genes was analyzed by Northern blot to identify ribosome arrest-dependent peptidyl-tRNA. The RBS, glyV and proL oligonucleotide probes were specific for the ribosome binding site of mRNA, tRNA3 Gly and tRNA2 Pro, respectively. The migration positions of full-length mRNA, truncated mRNA, tRNA3 Gly, peptidyl-tRNA3 Gly, and tRNA2 Pro are indicated. Samples containing over-expressed tRNA2 Pro are indicated by ↑[tRNA2 Pro]. The slower migrating species detected in the proL probe blot is probably incompletely processed tRNA2 Pro, as it is present in all over-expressed tRNA2 Pro samples, regardless of SecM expression.

SecM-arrested ribosomes contain prolyl-tRNAPro in the A site

Elegant studies have shown that SecM ribosome arrest is prevented if proline residues are replaced with the imino acid analog, azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (14). Based on this finding, it has been reasonably assumed that proline-166 is incorporated into the SecM nascent peptide during ribosome arrest (8,9,14). However, recent work from Ito and colleagues, as well as our analysis, indicates that ribosome arrest occurs prior to proline-166 addition (16). One model that is consistent with all available data postulates that prolyl-tRNAPro occupies the A site of the SecM arrested ribosome. If this model is correct, tRNAPro should be stably associated with arrested ribosomes.

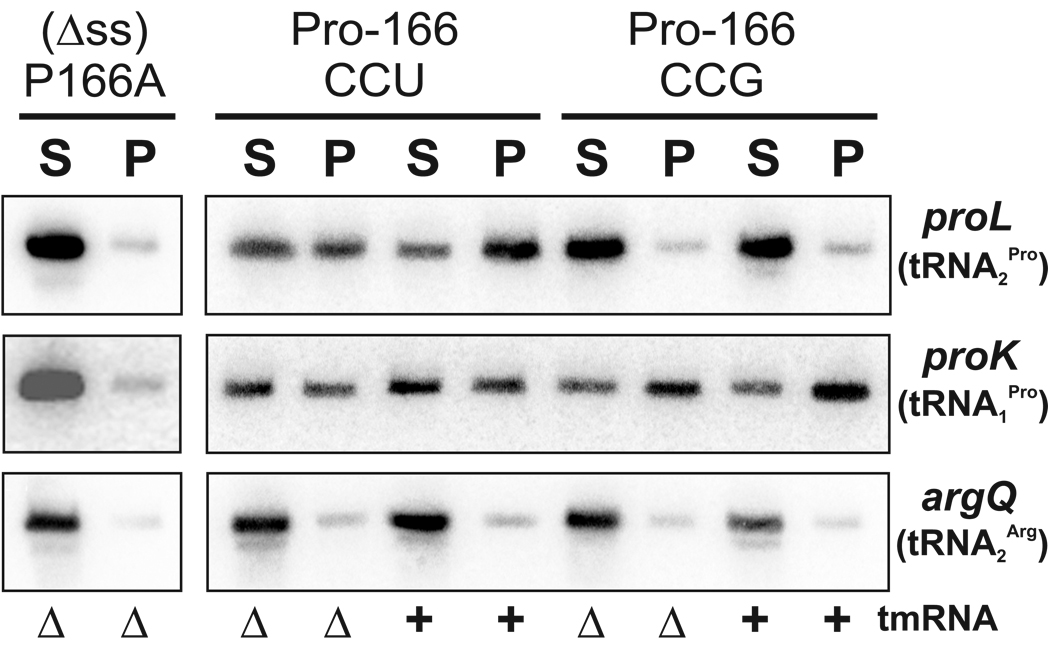

Extracts from cells expressing Flag-(Δss)SecM were separated into high-speed pellet and supernatant fractions by ultracentrifugation through sucrose cushions. Polyacrylamide gel analysis of RNA extracted from these fractions showed that the rRNA (i.e. ribosomes) was present in the pellet fraction, whereas the majority of tRNA was in the supernatant fraction (data not shown). Partitioning of tRNA to the supernatant fraction was confirmed by Northern analysis for tRNA2 Arg (Figure 4, argQ probe blot), which was not predicted to associate with SecM-arrested ribosomes. In contrast, a higher proportion of tRNA2 Pro was found in the pellet fractions from cells expressing Flag-(Δss)SecM, but not Flag-(Δss-P166A)SecM (Figure 4, proL probe blot). Enrichment of tRNAPro in pellet fractions was dependent upon cognate tRNA/codon interactions. tRNA2 Pro, the cognate tRNA for CCU and CCC codons, was not enriched in high-speed pellets if SecM proline-166 was encoded by CCG (Figure 4, proL probe blot), even though the CCG codon fully supports ribosome arrest (9). Moreover, although tRNA1 Pro partitioned to the pellet fractions when the CCU construct was expressed, significantly more tRNA1 Pro was found in the pellet fraction when its cognate CCG codon was used to code for proline-166 (Figure 4, proK probe blot). The partitioning of tRNA1 Pro to the ribosome fraction with the CCU construct may be due to association with trailing ribosomes within the SecM-stalled polysome, because tRNA1 Pro is not known to decode CCU and is found in the high-speed supernatant in the absence of ribosome arrest (Figure 4, (Δss)P166A lanes). Finally, the association of tRNAPro with pellet fractions was not inhibited by the tmRNA quality control system (Figure 4, ΔtmRNA vs. tmRNA+).

Figure 4. tRNAPro is associated with SecM-arrested ribosomes.

Northern blot analysis of RNA purified from supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions obtained by ultracentrifugation of cell lysates through sucrose cushions. Cells expressed Flag-(Δss)SecM in which proline-166 was encoded by CCU, CCG, or changed to alanine (P166A). The proL, proK and argQ oligonucleotide probes were specific for tRNA2 Pro (cognate for CCU and CCC), tRNA1 Pro (cognate for CCG), and tRNA2 Arg (cognate for CGU, CGC, and CGA), respectively. Samples from tmRNA+ and ΔtmRNA strains are indicated.

tmRNA activity at SecM-arrested ribosomes

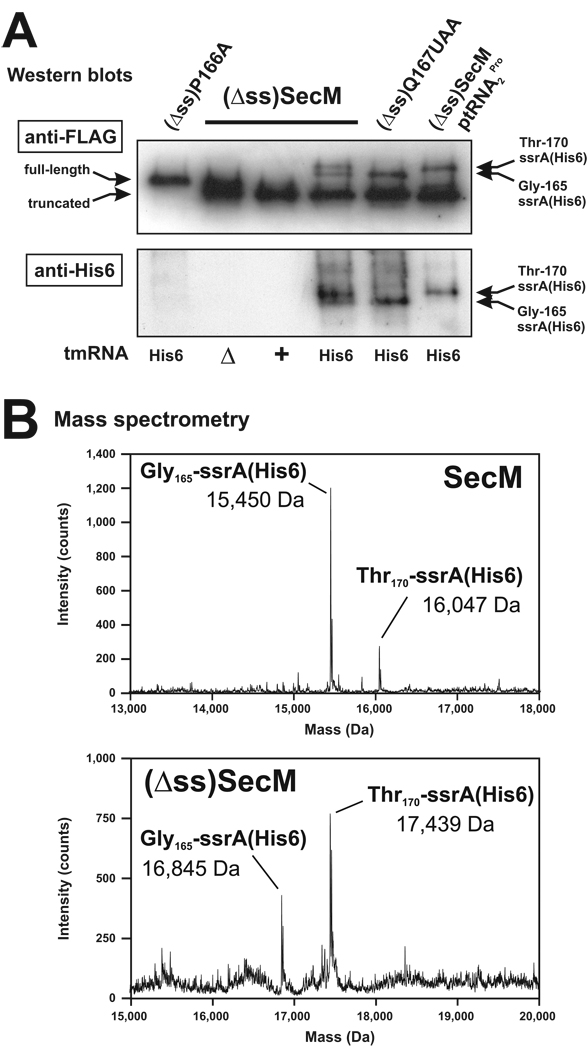

The data presented thus far indicate that tmRNA does not play a significant role in rescuing SecM-arrested ribosomes. However, published reports show SecM and SecM variants are ssrA-tagged by tmRNA as a consequence of ribosome arrest (27,28). We examined tmRNA-mediated peptide tagging of SecM proteins in cells that express tmRNA(His6), which encodes a hexahistidine-containing ssrA peptide that is resistant to proteolysis (18). Western blot analysis using antibodies specific for His6 detected two ssrA(His6)-tagged species of (Δss)SecM (Figure 5A, (Δss)SecM His6 lane). A similar ssrA(His6)-tagged doublet was observed with signal sequence-containing Flag-SecM (data not shown), but not with the Flag-(Δss-P166A)SecM protein, which does not cause ribosome arrest (Figure 5A, (Δss)P166A). All ssrA(His6)-tagged species were also detected by Western analysis using antibody specific for the N-terminal FLAG epitope (Figure 5A, anti-FLAG panel).

Figure 5. tmRNA activity at SecM-arrested ribosomes.

(A) Western blot analyses of Flag-(Δss)SecM variants expressed in tmRNA+, ΔtmRNA and tmRNA(His6) cells. Anti-His6 antibodies recognized ssrA(His6) peptide tags added to the C termini of Flag-(Δss)SecM proteins. Anti-FLAG antibody detected the N-terminal FLAG epitope present on all (Δss)SecM variants. Cells expressing the following proteins were analyzed: Flag-(Δss-P166A)SecM, (Δss)P166A; Flag-(Δss)SecM, (Δss)SecM; and Flag-(Δss-Q167UAA)SecM, (Δss)Q167UAA. The positions of all untagged and ssrA(His6)-tagged proteins are indicated by labeled arrows. Plasmid ptRNA2 Pro over-expresses tRNA2 Pro. (B) Mass spectrometry of ssrA(His6)-tagged SecM and Flag-(Δss)SecM proteins. Measured masses were consistent with proteins containing C-terminal ssrA(His6) tags added after SecM residues glycine-165 and threonine-170.

To determine the sites of tagging, we purified ssrA(His6)-tagged Flag-SecM and Flag-(Δss)SecM by Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography and subjected the purified proteins to mass spectrometry and N-terminal sequence analysis. Although Flag-SecM was initially expressed as an N-terminal FLAG fusion, the N-terminal amino acid sequence (AEPNA) of the purified protein indicated that the epitope tag had been removed along with the signal sequence peptide during secretion (data not shown). The masses of tagged SecM species were consistent with the addition of ssrA(His6) tags after glycine-165 (15,450 Da; calculated mass 15,451 Da) and threonine-170 (16,047 Da; calculated mass 16,047 Da) (Figure 5B, SecM spectrum). Similarly, Flag-(Δss)SecM was also tagged after residues corresponding to glycine-165 (16,845 Da; calculated mass 16,846 Da) and threonine-170 (17,439 Da; calculated mass 17,442 Da) (Figure 5B, (Δss)SecM spectrum). We suspected that the tagged proteins detected by Western blot analysis corresponded to the two species observed by mass spectrometry. These assignments were confirmed through analysis of the Flag-(Δss-Q167UAA)SecM protein, which was synthesized from a construct containing a mutation that changes glutamine-167 codon to a stop codon (UAA) (Figure 1A). The Flag-(Δss-Q167UAA)SecM protein lacks four C-terminal amino acid residues, but still causes ribosome arrest (9). Flag-(Δss-Q167UAA)SecM protein was tagged after glycine-165, but not after threonine-170 (Figure 5A, (Δss)Q167UAA and data not shown). Presumably, the premature stop codon prevented ribosomes from translating to the 3´ end of truncated mRNA.

The effect of tmRNA activity on total SecM protein production was examined by Western blot analysis using a monoclonal antibody specific for the N-terminal FLAG epitope present on all Flag-(Δss)SecM variants. Two species of Flag-(Δss)SecM accumulated in ΔtmRNA cells (Figure 5A, anti-FLAG panel, ΔtmRNA lane). The higher molecular weight protein represented full-length polypeptide and this species co-migrated with Flag-(Δss-P166A)SecM (which does not cause ribosome arrest) on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Figure 5A, anti-FLAG panel). The lower molecular weight species seen in ΔtmRNA cells corresponded to incompletely synthesized Flag-(Δss)SecM protein (to residue glycine-165) produced during ribosome arrest (Figure 5A , and data not shown). However, analyses of cetyl trimethylammonium bromide precipitates and isolated ribosomes indicated that most of the incompletely synthesized Flag-(Δss)SecM protein was not covalently linked to tRNA and therefore did not represent ribosome-bound nascent chains (data not shown). Therefore, incompletely synthesized Flag-(Δss)SecM polypeptide chains were released from the arrested ribosome in a tmRNA-independent manner. In contrast to ΔtmRNA cells, full-length Flag-(Δss)SecM protein was not detected in tmRNA+ cells (Figure 5A, anti-FLAG panel, tmRNA+ lane). Presumably, the full-length Flag-(Δss)SecM protein was ssrA-tagged and degraded rapidly in wild-type cells. Similarly, full-length Flag-(Δss)SecM did not accumulate to very high levels in tmRNA(His6)-expressing cells, although the two ssrA(His6)-tagged species were readily detected (Figure 5A, anti-FLAG panel).

Prolyl-tRNAPro in the A site inhibits tmRNA activity

SsrA-tagging after glycine-165 appears to contradict the other data indicating that tmRNA plays no significant role in resolving SecM-arrested ribosomes. However, this work and previous studies relied upon SecM over-expression (27,28), which is predicted to deplete limiting tRNAPro species. tRNA3 Gly, which holds the SecM nascent chain during ribosome arrest, is found at ~4,400 molecules per E. coli cell, whereas tRNA2 Pro and tRNA3 Pro, which occupy the arrested ribosome A site, are present at only ~1,300 copies per cell (29). Therefore, if the number of SecM-arrested ribosomes exceeds 1,300 per cell, a second population of stalled ribosomes with unoccupied A sites will accumulate due to prolyl-tRNAPro sequestration, potentially allowing for adventitious ssrA-tagging after glycine-165.

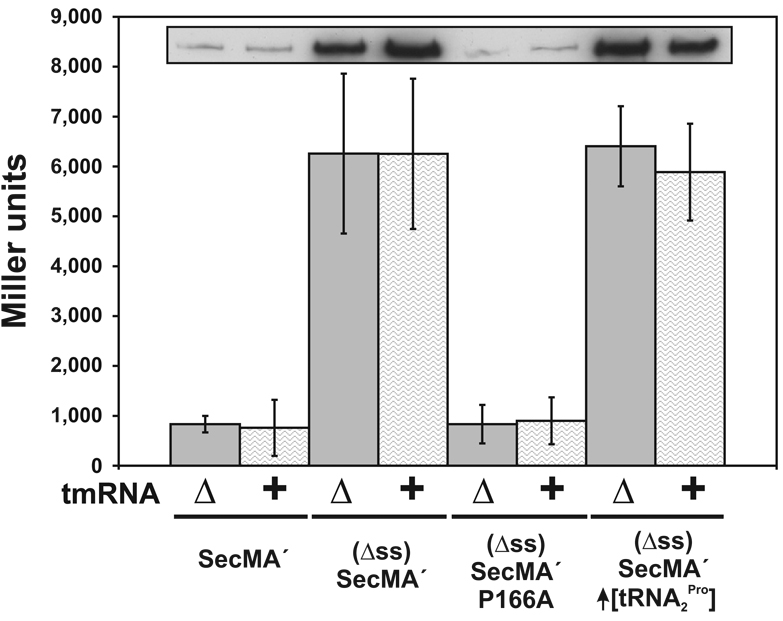

To test this model, we over-expressed tRNA2 Pro and examined the effects on ssrA peptide tagging and three other properties of SecM ribosome arrest: i) nascent peptidyl-tRNA stability, ii) cleavage of flag-secM´ mRNA, and iii) regulation of secA translation. Over-expression of tRNA2 Pro significantly suppressed ssrA(His6)-tagging after glycine-165, but increased tagging after threonine-170 (Figure 5A, (Δss)SecM – ptRNA2Pro lane). Although tmRNA activity was significantly altered, tRNA2 Pro over-expression had no effect on nascent peptidyl-tRNA3 Gly accumulation (Figure 3, glyV probe blot), and actually appeared to increase flag-secM´ mRNA cleavage (Figure 3, RBS probe blot). Finally, tRNA2 Pro over-expression had no effect on the regulation of secA translation. We made secA´∷lacZ translational fusions and confirmed that deletion of the SecM signal sequence increased SecA´-LacZ expression, whereas further introduction of the P166A mutation reduced fusion protein synthesis (Figure 6). Over-expression of tRNA2 Pro had no significant effect on the ribosome arrest-dependent increase in β-galactosidase activity (Figure 6). Moreover, deletion of tmRNA had no effect on SecA´-LacZ expression, as determined by Western blot and β-galactosidase activity analyses (Figure 6). We also attempted to examine the effects tRNA1 Pro over-expression on ribosome arrest from constructs that encoded proline-166 as CCG. Unfortunately, all plasmid clones carrying the proK gene under its own promoter also contained mutations in the tRNA1 Pro-encoding sequence (data not shown). Seven distinct mutations were found mapping to the D-arm, T-arm, anticodon loop, and the promoter (data not shown). These results suggest that high-level over-expression of tRNA1 Pro is deleterious to the cell.

Figure 6. Over-expression of tRNA2 Pro does not affect translational regulation of SecA.

SecM-dependent regulation of SecA-LacZ fusion protein expression was analyzed by β-galactosidase activity assay and Western blot analysis (inset). The SecA-LacZ translational fusion was expressed from constructs in which SecM was secreted [SecMA´], not secreted [(Δss)SecM], or failed to elicit ribosome arrest [(Δss)SecM P166A]. Western blot analysis was performed with polyclonal antibodies specific for E. coli β-galactosidase. tRNA2 Pro was over-expressed from plasmid ptRNA2 Pro.

DISCUSSION

Several lines of evidence indicate that the primary SecM-mediated ribosome arrest is resistant to A-site mRNA cleavage and subsequent tmRNA recruitment. First, although the secM mRNA was truncated in a ribosome arrest-dependent manner, the cleavage sites were 13 to 19 nucleotides downstream of the A site codon. Second, the steady-state number of SecM-arrested ribosomes (as determined by Northern analysis of nascent peptidyl-tRNA) was not significantly affected by tmRNA. Third, incompletely synthesized SecM protein (to residue glycine-165) accumulated in tmRNA+ and tmRNA(His6)-expressing cells. Fourth, SecM-dependent regulation of secA translation was essentially identical in ΔtmRNA and tmRNA+ cells (27). Finally, A site-bound tRNA2 Pro inhibits ssrA-tagging after SecM glycine-165. The surprising discovery of A site-bound prolyl-tRNAPro has also been recently reported by Ito and colleagues (16). That study used entirely different methods than ours to characterize arrested ribosomes produced in vitro (16), and is entirely congruent with our analysis of the in vivo SecM ribosome arrest. Altogether, our data strongly suggest that tmRNA recruitment during the primary ribosome arrest is an artifact of SecM over-expression, and that A-site mRNA cleavage and ssrA-tagging at this site do not occur under physiological conditions. We feel this conclusion makes biological sense because A-site cleavage is predicted to interfere with cis-acting SecM regulation of secA translation initiation. Moreover, co-translational secretion of the SecM nascent peptide ensures that SecA is synthesized in close proximity to the inner membrane (30), a phenomenon that presumably requires synthesis of SecM and SecA from the same mRNA molecule.

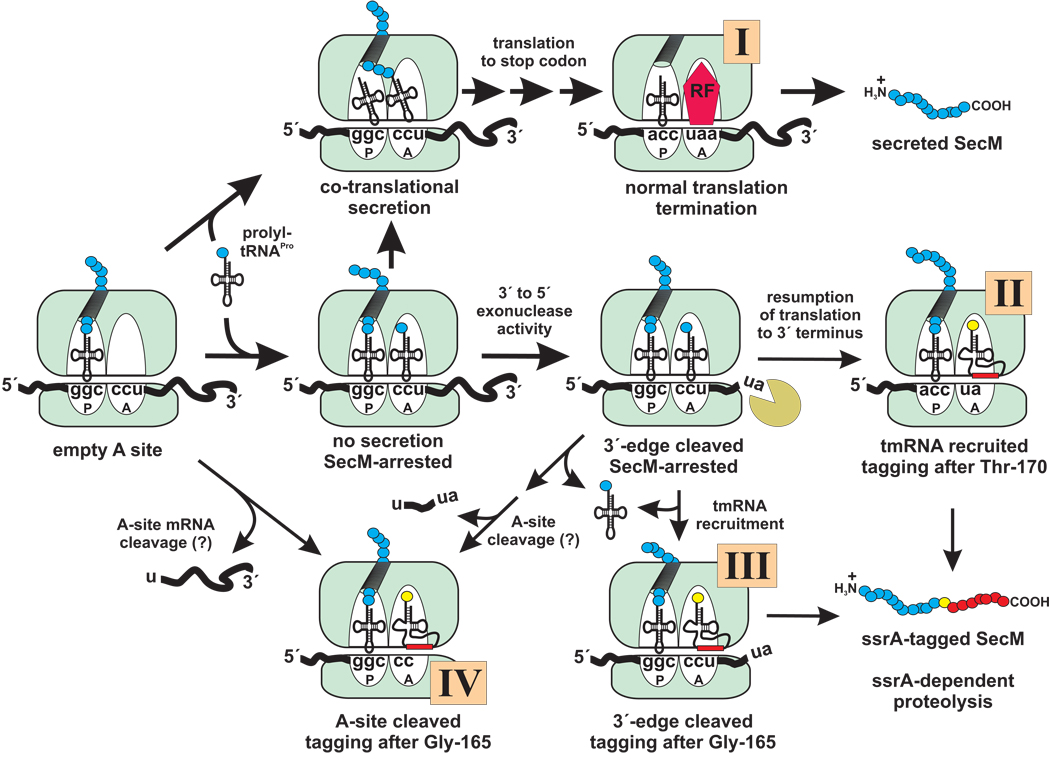

Deletion of the SecM signal sequence prevents co-translational secretion and thereby precludes the mechanism that normally alleviates ribosome arrest (14). Secreted SecM also elicited ribosome arrest in our study, presumably because the over-expressed protein saturated the secretion machinery. The (Δss)SecM-mediated ribosome arrest exhibits a t1/2 > 4 – 5 minutes in vivo (14), which exceed the half-life of bulk E. coli mRNA turnover (~2.4 min at 37°C) (31). Thus, prolonged translational pausing allows degradation of the downstream mRNA to the 3´ edge of the arrested ribosome (Figure 7). Presumably, the 5´ portion of the message is protected by ribosomes queued behind the primary SecM-arrested ribosome. The influence of SecM ribosome arrest on mRNA degradation appears to differ from other reported ribosome pauses, which tend to stabilize mRNA downstream of the arrest site (32–34). Although specific endonuclease cleavage between cistrons has been observed in E. coli operons (35), we find the same cleavages in mRNAs that lack the secM-secA intergenic region. Moreover, the cleavage appears to require ribosome arrest, arguing against a sequence specific endonuclease activity. Our observations suggest that 3´→5´ exoribonucleases generate the 3´ termini of truncated secM messages. First, cleavage occurred downstream of the A-site codon, at sites consistent with the 3´ border of a stalled E. coli ribosome (36,37). Second, the proportion of +13 and +19 cleavage products was dependent upon exoribonuclease activities present in the cell. Longer cleavage products accumulated in the absence of either RNase R or PNPase, both of which degrade secondary structure-containing RNAs more efficiently than RNase II (38,39). Although RNase R and PNPase are not known to work together, our data suggests that these enzymes may cooperate to convert the +19 cleavage product to the +13 product. Finally, RNase II can indirectly inhibit the degradation of structured mRNAs by removing 3´ single stranded regions required by PNPase to bind substrate (39,40). These biochemical properties are consistent with the accumulation of cleavage products in our exoribonuclease knock-out strains.

Figure 7. Fates of SecM-arrested ribosomes.

Ribosomes that synthesize SecM have at least four distinct fates. (I) Ribosome arrest is prevented if prolyl-tRNAPro binds the A site during co-translational secretion of the SecM nascent chain. Such ribosomes continue to the stop codon and terminate translation normally. (II) Binding of prolyl-tRNAPro in the absence of co-translational secretion results in ribosome arrest and allows degradation of downstream mRNA to the 3´ edge of the arrested ribosome by exoribonucleases. Resumption of translation on 3´-edge cleaved mRNA leads to secondary ribosome arrest at the 3´ end of the message, recruitment of tmRNA, and ssrA-tagging of SecM after threonine-170. (III) If the A site is unoccupied, tmRNA may be directly recruited to ribosomes arrested on 3´-edge cleaved mRNA, resulting in ssrA-tagging after glycine-165. (IV) Ribosomes with unoccupied A sites may undergo A-site mRNA cleavage at a low rate, also allowing ssrA-tagging after glycine-165. Exoribonuclease cleavage to the 3´ edge of the arrested ribosome could also precede A-site mRNA cleavage. Protein release factor is labeled RF, and the peptidyl-tRNA and aminoacyl-tRNA binding sites are labeled P and A, respectively.

The details of mRNA cleavage notwithstanding, it is interesting that the secM stop codon is in position to be cleaved during prolonged ribosome arrest. SecM-arrested ribosomes clearly resumed translation, and upon reaching the 3´ end of the truncated mRNA, they stalled for a second time (Figure 7). However, tmRNA is readily recruited to ribosomes stalled at the extreme 3´ termini of mRNAs, and SecM was ssrA-tagged after the C-terminal residue threonine-170 (Figure 7, ribosome fate II). Because little full-length (Δss)SecM protein accumulated in tmRNA+ or tmRNA(His6) cells, it appears that degradation of mRNA to the ribosome edge preceded the resumption of translation. It is unclear whether exoribonuclease cleavage also leads to ssrA-dependent degradation of SecM under physiological conditions. Secreted SecM was shown to be rapidly degraded in tmRNA+ cells (14), and we find the non-degradable ssrA(His6) tag stabilizes SecM in the periplasm. However, both of these studies employed SecM over-expression. At lower expression levels, co-translational secretion of SecM is expected to prevent ribosome arrest, and thereby inhibit mRNA cleavage and subsequent tmRNA recruitment/ssrA-tagging (Figure 7, ribosome fate I). In any event, prolonged ribosome arrest stimulates SecA expression, so significant protein synthesis must occur prior to degradation of the downstream secA cistron.

A-site mRNA cleavage and tmRNA activities were clearly not able to resolve the majority of primary SecM-arrested ribosomes. However, ssrA-tagging after glycine-165 indicates limited tmRNA recruitment during primary ribosome arrest, at least when SecM is over-expressed. Ivanova et al. showed tmRNA is recruited to ribosomes stalled on mRNAs where the 3´ terminus is 12 nucleotides downstream of the A site codon, albeit at a ~20-fold lower rate than maximum (41). Therefore, cleavage of mRNA to the 3´ edge of the arrested ribosome could allow relatively inefficient tmRNA recruitment, provided the A site is not occupied with prolyl-tRNAPro (Figure 7, ribosome fate III). Alternatively, limited A-site mRNA cleavage may have occurred under SecM over-expression conditions (Figure 7, ribosome fate IV). It appears that A-site nuclease activity is restricted to codons within unoccupied A sites (1,2), so presumably A-site cleavage in this instance would be an artifact of SecM over-expression. Based on Northern blot analysis, approximately 60% of cellular tRNA3 Gly is sequestered as SecM nascent peptidyl-tRNA during SecM over-expression. This corresponds to roughly 2,600 SecM arrested ribosomes per cell, of which only ~1,300 can simultaneously contain A-site prolyl-tRNAPro (29). Therefore, we estimate ~50% of the SecM-arrested ribosomes have unoccupied A sites in the absence of compensatory tRNA2 Pro over-expression, in accord with recent studies of SecM-arrested ribosomes (15,16). Given incomplete A-site occupancy, perhaps the lack of A-site mRNA cleavage reflects sequence specificity of the A-site nuclease. The RelE protein shows marked preference for A-site codons, cleaving CAG and UAG at the highest rate (1). However, we have observed RelE-independent A-site mRNA cleavage at several different codons, suggesting that many sequences are potential substrates2 (2).

Alternatively, the low rate of A-site mRNA cleavage may be due to the substantial structural rearrangements that occur in the ribosome during SecM-mediated arrest (15). SecM-induced structural rearrangements originate in the 50S exit channel and are propagated to the 30S subunit via inter-subunit bridges and ribosome-bound tRNAs (9,15). Although structural changes are transmitted by tRNA, SecM-arrested ribosomes adopt the same conformation independent of A-site bound prolyl-tRNAPro (15). Several elements of 16S rRNA are rearranged during ribosome arrest, including helix 44, which forms part of the 30S A site and makes contact with A-site mRNA (15). Clearly, alteration of A-site structure could significantly affect A-site nuclease activity, be it catalyzed by the ribosome or a trans-acting factor. Interestingly, Aiba and colleagues showed that expression of a fusion protein containing the SecM-derived residues G161IRAGP166 resulted in significant mRNA cleavage at sites immediately adjacent to the A-site codon, although the majority of cleavages still occurred at other positions corresponding to the 3´ and 5´ edges of the paused ribosome (28). We also observed similar cleavages near the A-site codon when expressing a fusion protein containing the longer SecM-derived Q149FSTPVWISQAQGIRAGP166 sequence (Figure 2B), but failed to detect these mRNA cleavages when expressing full-length SecM sequences. Perhaps the full-length SecM nascent peptide is required for complete structural rearrangement and inhibition of A-site mRNA cleavage.

Gene regulation by translational pausing has long been recognized in prokaryotes, although its importance is still often underestimated. Indeed, the SecM ribosome arrest is a newly characterized example of translational attenuation, which was shown to control inducible expression of erythromycin and chloramphenicol resistance genes over twenty years ago (42–45). The role of translational pausing in transcriptional attenuation of the E. coli trp operon was recognized even earlier (46,47). In each case, A-site mRNA cleavage and tmRNA activities have the potential to interfere with regulation by “rescuing” paused ribosomes. However, in our view, it makes little sense to employ regulatory strategies that are undermined by translational quality control systems, and we predict that regulatory ribosome pauses are generally immune to A-site cleavage and tmRNA activities. The mechanisms involved are likely varied, and characterization of other ribosome pauses will hopefully increase our understanding of the molecular requirements for A-site mRNA cleavage.

Footnotes

We thank Laura Holberger, Kathleen McGinness, Sean Moore, and Bob Sauer for helpful discussions, Christopher Cain and Amy Chen for conducting preliminary experiments, Jason Sagert for N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis, and Les Wilson and David Chapman for use of equipment. Mass spectrometry was performed in the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry Mass Spectrometry Facility at UC Santa Barbara with the assistance of Dr. James Pavlovich. This work was supported by start-up funds from UC Santa Barbara, and a grant from Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital and the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The abbreviations used are: A site, aminoacyl-tRNA binding site; P site, peptidyl-tRNA binding site; tmRNA, transfer-messenger RNA; IPTG, isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside; OD600, optical density at 600 nm; PNPase, polynucleotide phosphorylase; NTA, nitrilotetraacetic acid; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance

Garza-Sánchez and Hayes, unpublished results

REFERENCES

- 1.Pedersen K, Zavialov AV, Pavlov MY, Elf J, Gerdes K, Ehrenberg M. Cell. 2003;112:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes CS, Sauer RT. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:903–911. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunohara T, Jojima K, Yamamoto Y, Inada T, Aiba H. RNA. 2004;10:378–386. doi: 10.1261/rna.5169404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karzai AW, Roche ED, Sauer RT. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:449–455. doi: 10.1038/75843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keiler KC, Waller PR, Sauer RT. Science. 1996;271:990–993. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovett PS, Rogers EJ. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;60:366–385. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.366-385.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tenson T, Ehrenberg M. Cell. 2002;108:591–594. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00669-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakatogawa H, Murakami A, Ito K. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakatogawa H, Ito K. Cell. 2002;108:629–636. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNicholas P, Salavati R, Oliver D. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;265:128–141. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murakami A, Nakatogawa H, Ito K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:12330–12335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404907101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori H, Ito K. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:494–500. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butkus ME, Prundeanu LB, Oliver D. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:6719–6722. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.22.6719-6722.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakatogawa H, Ito K. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitra K, Schaffitzel C, Fabiola F, Chapman MS, Ban N, Frank J. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:533–543. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muto H, Nakatogawa H, Ito K. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes CS, Bose B, Sauer RT. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:33825–33832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes CS, Bose B, Sauer RT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:3440–3445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052707199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng ZF, Zuo Y, Li Z, Rudd KE, Deutscher MP. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14077–14080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiyar A, Leis J. Biotechniques. 1993;14:366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varshney U, Lee CP, RajBhandary UL. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:24712–24718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto Y, Sunohara T, Jojima K, Inada T, Aiba H. RNA. 2003;9:408–418. doi: 10.1261/rna.2174803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpousis AJ. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanzo NF, Li YS, Py B, Blum E, Higgins CF, Raynal LC, Krisch HM, Carpousis AJ. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2770–2781. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collier J, Bohn C, Bouloc P. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:54193–54201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sunohara T, Jojima K, Tagami H, Inada T, Aiba H. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:15368–15375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong H, Nilsson L, Kurland CG. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;260:649–663. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakatogawa H, Murakami A, Mori H, Ito K. Genes Dev. 2005;19:436–444. doi: 10.1101/gad.1259505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regnier P, Arraiano CM. Bioessays. 2000;22:235–244. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200003)22:3<235::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bechhofer DH, Zen KH. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:5803–5811. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5803-5811.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dreher J, Matzura H. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5:3025–3034. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loomis WP, Koo JT, Cheung TP, Moseley SL. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:693–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Altman S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:13213–13218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235589100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fredrick K, Noller HF. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1125–1131. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jerinic O, Joseph S. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;304:707–713. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng ZF, Deutscher MP. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21624–21629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coburn GA, Mackie GA. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:1061–1074. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hajnsdorf E, Steier O, Coscoy L, Teysset L, Regnier P. EMBO J. 1994;13:3368–3377. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ivanova N, Pavlov MY, Felden B, Ehrenberg M. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruckner R, Dick T, Matzura H. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1987;207:486–491. doi: 10.1007/BF00331619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dubnau D. EMBO J. 1985;4:533–537. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hahn J, Grandi G, Gryczan TJ, Dubnau D. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1982;186:204–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00331851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lovett PS. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:1–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.1-6.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yanofsky C. Nature. 1981;289:751–758. doi: 10.1038/289751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zurawski G, Elseviers D, Stauffer GV, Yanofsky C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1978;75:5988–5992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.12.5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]