Abstract

Research indicates that developing public health programs to modify parenting behaviors could lead to multiple beneficial health outcomes for children. Developing feasible effective parenting programs requires an approach that applies a theory-based model of parenting to a specific domain of child health and engages participant representatives in intervention development. This article describes this approach to intervention development in detail. Our presentation emphasizes three points that provide key insights into the goals and procedures of parenting program development. These are a generalized theoretical model of parenting derived from the child development literature, an established eight-step parenting intervention development process and an approach to integrating experiential learning methods into interventions for parents and children. By disseminating this framework for a systematic theory-based approach to developing parenting programs, we aim to support the program development efforts of public health researchers and practitioners who recognize the potential of parenting programs to achieve primary prevention of health risk behaviors in children.

Introduction

In public health research, there is broad interest in understanding the role of parenting behaviors as determinants of child health risk behaviors, including tobacco use [1, 2], alcohol use [3], drug abuse [4], violence [5], diet [6, 7], physical activity [8] and unsafe driving [9, 10]. This body of work makes clear that developing public health programs to modify parenting behaviors could lead to multiple beneficial health outcomes for children. This article presents a framework for developing parenting interventions that is derived from our studies of parenting and child smoking prevention [11–17].

Parenting interventions to prevent initiation of smoking by children

The Smoke-free Kids intervention [16, 17] is the only child smoking prevention program that engages parents in a comprehensive home-based program of anti-smoking socialization with elementary school-aged children. The first version of this program, tailored for parents who smoke, was effective in modifying smoking-specific parenting practices [16] and in lowering the odds that children would initiate smoking [17]. The second version of the program, tailored for non-smoking parents, is being evaluated in an ongoing randomized trial (RO1CA106316).

As part of our 10-year program of research to develop and test the Smoke-free Kids parenting program, we have produced an increasingly well-articulated and structured process of developing parenting interventions to promote health-protective behaviors in children. The process we formulated in our initial randomized trial has been refined and improved in the ongoing trial, and we have continued to refine this process in projects targeting other domains of parenting as it relates to children's alcohol consumption, media use, physical activity and diet. This intervention development process has become a vital asset in our overall program of research on parenting, child socialization and child health outcomes.

We regularly receive requests to provide access to our parenting program materials. Just as often, however, we are asked to explain how we go about developing a parenting intervention. In the interest of disseminating this information, we have prepared this article in which we explain our parenting intervention development process in detail. We give particular emphasis to three aspects of our approach that, based on feedback from other investigators, provide the most insight into the goals and procedures of parenting program development. These are (i) the theoretical model that underlies our approach to intervening to modify parenting variables, (ii) the eight-step intervention development process we follow and (iii) methods for integrating parent–child experiential learning methods into intervention design. Although this article uses the Smoke-free Kids intervention as the exemplar, the process we describe can be applied to develop interventions targeting other domains of parenting and child health.

Theoretical basis of parenting interventions

As children develop, they become increasingly aware of and responsive to social norms. Specifically, children learn to modulate their behaviors based on the standards of thought and action that are accepted or rejected by members of their primary social groups [18–22]. Children's normative socialization occurs via everyday processes of influence and learning, principally interpersonal communication and observation of and direct experience with others. Children internalize social norms gradually and cumulatively as they are exposed to myriad inputs from multiple sources, including parents, siblings, friends, teachers and mass media. Although social norms develop from interactions with others, norms that are internalized (i.e. accepted privately) can influence thoughts and actions even when personal referents for specific norms are absent [23, 24].

During early and middle childhood, children are socialized primarily by their parents [20, 25]. To the extent that parents can be guided to socialize children in ways that prevent development of health risk behaviors, parents have the potential to play a lead role in public health interventions that promote child well-being. Engaging parents in public health interventions not only creates the opportunity to modify child socialization processes within the family but also has the potential, via program-guided parenting activities, to modify children's exposure to and interpretation of social influences originating beyond the home environment (e.g. mass media, peers). Involving parents also creates the opportunity to provide children with sustained exposure to pro-health socialization; ongoing exposure is key to child internalization of social norms that protect health.

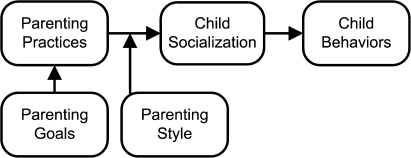

To introduce key parenting variables, we utilize Darling and Steinberg's integrative model [26], which incorporates the empirically informed perspectives on parenting and child socialization put forth by leading developmental theorists, including Baumrind [27, 28], Maccoby [20, 25] and Dornbusch [29, 30]. This model incorporates variables from two previously distinct areas of socialization research: studies of specific parenting practices and studies of global parenting characteristics (Fig. 1). In our judgment, this model is comprehensive enough to guide development of universal interventions that have primary prevention goals (e.g. child smoking prevention or child obesity prevention). That is, the integrative model provides a theory-based map of the general categories of parenting variables that can be targeted by parenting programs for child health promotion. Three principal categories of parenting variables—parenting practices, parenting goals and parenting style—are shown to influence children's socialization and, ultimately, their behaviors.

Fig. 1.

Model of parenting variables, adapted from Darling and Steinberg's integrative model.

Parenting practices refers to the content of parental communication, rule setting, guided experience, modeling, monitoring and other everyday processes of child socialization. Parenting practices are the most observable aspect of parenting behavior: what parents say and do, what rules they set, what norms they reinforce—all are parenting practices. Parenting practices are domain specific; common domains of parenting practice aim to socialize children about moral issues (e.g. telling the truth), conventional issues (e.g. cleaning one's room) and education (e.g. doing homework) [31]. The primary aim of parenting interventions is to engender or strengthen parenting practices within domains associated with specific child health outcomes. The Smoke-free Kids program aims to modify parenting practices that influence how children are socialized about cigarette smoking. Other health promotion interventions might aim to modify parenting practices that influence how children are socialized specific to alcohol use, diet, physical activity, aggression or sexual behaviors.

Parenting goals indicate why parents undertake certain parenting practices. Parenting goals pertain to children's development of specific skills or attributes (e.g. social skills, academic success) or to their development of more global qualities (e.g. self-esteem, independence, physical health) [26]. Parenting goals motivate parents to utilize practices they believe will increase the likelihood that children will develop desired attributes or decrease the likelihood of undesired attributes. Thus, the effect of parenting goals on child socialization is indirect (i.e. mediated by parenting practices; Fig. 1). Parenting interventions like Smoke-free Kids are theoretically more likely to engage parents if they increase the salience and relevance of goals that specifically support the targeted domain of smoking-specific parenting practices. For example, most parents who smoke are highly motivated to prevent their children from experiencing nicotine addiction in the short term and smoking-related diseases in the long term. Anchoring program recommended child socialization activities to these goals is another aspect of intervention design in Smoke-free Kids.

Parenting style is a global attribute of parenting behavior; it indicates how parents interact with their children across multiple domains of influence. Parenting style is generally operationalized using two dimensions of general parenting behavior [20, 32, 33]: one, labeled ‘demandingness’ or ‘control’, refers to the confidence and skill with which parents set disciplinary standards and provide supervision, monitoring and regulation of children's behavior. The other, labeled ‘responsiveness’ or ‘support’, refers to parental capacity to be affectionate and to maintain awareness of children's psychosocial states and needs. This two-dimensional model has been widely used by developmental psychologists to define four parenting styles: authoritative (highly demanding and highly responsive), permissive (responsive but relatively undemanding), authoritarian (demanding but relatively unresponsive) and indifferent (relatively undemanding and unresponsive) [20, 29, 32–36]. Of these, authoritative parenting, which balances firm discipline with strong parent–child connectedness, has been found to reduce children's risk of smoking and other health risk behaviors [2, 27, 37, 38].

The integrative model [26] conceptualizes parenting style as a contextual variable with implications for the effectiveness of parenting practices in specific domains. For example, several parents might attempt to teach children to resist peer influences to try smoking, but, due to differences in parenting style, they will likely differ with regard to the effectiveness of these practices. This component of the integrative model indicates that intervention programs should incorporate known attributes of an effective parenting style (e.g. communication skills, openness to child input on family decisions) in order to optimize the effectiveness of targeted parenting practices. For example, the intervention should teach parents to communicate specific expectations for their children that are reinforced by fair and logical consequence as well as supportive parenting behaviors (e.g. praise).

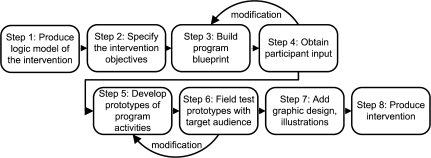

A stepped approach to developing parenting interventions

The principal challenge in developing any public health intervention is figuring out how to proceed from a purely theoretical position (e.g. understanding the integrative model or other theoretical model) to having an intervention that is ready to be delivered and evaluated. In our research, we have developed an eight-step process that enables us to address this challenge (Fig. 2). Key features of this eight-step process are expected to enhance both the efficacy and the dissemination potential of an intervention. Specifically, by using theory to inform practice, relying on the research literature to specify program objectives, engaging members of the target audience in intervention content development and allocating resources to enhance the visual and production qualities of intervention materials, we aim to optimize the appeal, perceived relevance, usability and, ultimately, utilization of the intervention. These attributes contribute to program efficacy in the short term and to the potential for program dissemination in the long term. The sections that follow describe this eight-step process in detail, with the Smoke-free Kids program as the exemplar.

Fig. 2.

Eight-step parenting intervention development process.

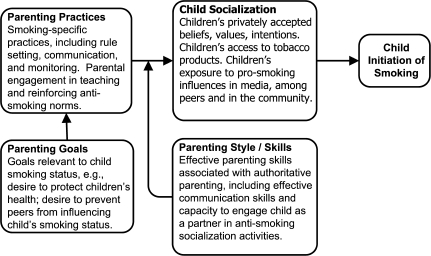

Step 1: produce a logic model of the intervention

Logic models synthesize theory and research to produce a framework for intervention design. The logic model developed for the Smoke-free Kids intervention (Fig. 3) synthesizes our theory-based model [26] with extant research that identifies parenting variables and child variables associated with the target health outcome—initiation of smoking by children. Because this is a logic model for intervention development, only modifiable variables are shown in the model; other factors known to explain variance in child smoking behavior (e.g. socioeconomic status) are excluded.

Fig. 3.

Step 1: logic model for the Smoke-free Kids intervention.

The Smoke-free Kids program logic model (Fig. 3) indicates that smoking-specific parenting practices are a primary target of the intervention. That is, the principal aim of the intervention materials and activities is to modify parenting practices that are hypothesized to influence child attributes that predict initiation of smoking. The model also identifies parenting goals that motivate parenting practices specific to smoking prevention. Some intervention materials and activities are needed that focus on parenting goals in order to strengthen parental motivation for implementing the recommended parenting practices. The logic model also identifies general parenting skills, known to be characteristic of an effective parenting style [27], that, per our theoretical model [26], moderate the effect of parenting practices on children's smoking-specific socialization. Known effective parenting skills, such as communication and monitoring skills, are incorporated into the content of the intervention materials and the structure of intervention activities in order to enhance the effectiveness of the recommended parenting practices.

Step 2: specify precise unambiguous intervention objectives

Intervention objectives are extracted from a detailed review of the relevant current research literature; objectives specify what variables (including knowledge, beliefs, values, intentions and behaviors) the intervention aims to modify. By articulating exactly what the intervention will try to change, the development of unambiguous intervention objectives adds an important level of precision to the information collected in Step 1. This precision is essential because each objective statement identifies something the intervention must accomplish, and precisely worded statements provide the benchmarks needed to complete subsequent steps. Examples of 10 (of 26 total) objectives specified for the Smoke-free Kids intervention are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Sample objectives for the Smoke-free Kids parenting program

| • Parents will use basic effective parent–child communication skills (e.g. reflective listening). |

| • Parents will gain confidence that they can reduce their children's risk of smoking. |

| • Parents and children will discuss smoking-specific family values and expectations. |

| • Parents and children will establish a social contract that specifies that the children will avoid any contact with or use of cigarettes and that parents will value children's smoke-free status. |

| • Parents and children will counter the pro-smoking images and messages in movies, print ads and other media. |

| • Children will practice managing pro-smoking influences from peers. |

| • Parents will monitor situations in which children will have access to cigarettes and experience social pressures to try cigarette smoking. |

| • Children will practice what they can say/do so that they can avoid exposure to secondhand smoke in cars, homes and elsewhere. |

| • Parents will reinforce/reward children for articulating or complying with family norms specific to cigarette smoking. |

| • Parents will establish household rules to restrict or ban indoor smoking in the family home. |

When measured over time, attainment of discrete objectives can be used to evaluate the immediate effects of an intervention. Indeed, a useful test of whether an intervention objective is stated with sufficient precision is whether it is clear how to measure whether the objective has been achieved.

Step 3: build an intervention blueprint

During Step 3, the research team brainstorms ideas for program activities so that each intervention objective is paired with one or more potential program activities for meeting that objective. The end product of Step 3—an intervention blueprint—marries the set of intervention objectives with a set of potential program activities intended to engage participants in reading, communicating, observing or behaving in ways that facilitate achievement of the objectives.

Take, for example, the last objective listed in Table I: ‘Establish household rules to restrict or ban indoor smoking in the family home’. A potential program activity the team might identify is one that involves parents and children in working together to decide where to maintain smoke-free zones in the home and involving children in designating the agreed-upon zones (by, e.g., using kits to create colorful posters that designate smoke-free rooms or areas). A full matrix of ideas like these, each of which marries an objective with potential program activities, forms the intervention blueprint. As activity ideas are vetted in focus groups with parents (Step 4), the blueprint is gradually refined by eliminating activities that do not pass muster in focus group testing.

The completed Smoke-free Kids intervention blueprint includes roughly twice as many program activities as specific objectives. This ratio of activities to objectives was intentional because it allowed us to develop activities that gradually develop key skills (by, e.g., breaking one objective into two or three requisite parts or by involving participants in increasingly challenging activities each focused on a single objective). With this ratio of activities to objectives, interventions can also incorporate repetition and therefore improved learning specific to certain intervention objectives.

Step 4: obtain participant input before developing intervention materials

After identifying potential program activities, the research team uses focus groups of parents who have children in the target age range to critique and then improve (or reject) the activities identified in Step 3. During focus groups, a planned activity is explained, displayed in draft form and/or demonstrated; parents are asked to provide feedback regarding clarity of purpose, appeal, perceived feasibility, barriers to implementation, likely utility and so forth. For example, after seeing some sample materials, parents would be asked if they and their children would be comfortable role-playing peer refusal strategies together and if the demonstrated board game approach would be appealing for the activity. We would also solicit ideas for specific scenarios to use with the role-play cards. If parents perceive significant barriers to implementing a proposed activity, they are asked to suggest alternative means of achieving the same objective. Some activity ideas are rejected outright at this step, requiring the research team to revise the blueprint from Step 3 by identifying new ideas for intervention activities for the relevant objective. Other activity ideas will be retained but modified substantially based on feedback from parents (Fig. 2). For the more challenging objectives, multiple rounds of focus groups can be required before a feasible appealing activity is identified for that objective. The end product of Step 4 is a more detailed intervention blueprint that includes activities that have been vetted by parents from the target population.

Steps 5 and 6: develop and field test prototypes of intervention activities

Prototypes are draft versions of intervention activities; prototypes are created by compiling the messages, images and supplemental materials needed to operationalize each program activity. Compared with final versions of program content, prototypes typically contain the same messages and instructional content, but draft versions of images (e.g. crude copies of smoking ads or a partial example of a game board), and no professionally printed, colored graphic design features or layout.

The key procedural goal of field testing is having people from the target population use each prototype under realistic conditions and then provide detailed feedback on their utilization experience. In our research protocols, we typically mail the same set of three activity prototypes to five parent–child dyads, give each dyad 3 weeks to use the materials and then follow with a 1-hour debriefing interview with parents. This is an extensive structured interview in which we collect detailed information about wording choices and comprehension, instructional clarity, level of interest, characterizations and colors, layout and visual clarity, time required for use, ease of use and barriers to use. Parents also return written notes that, per our request, they make on the prototype materials as they use them with their children. Information from the prototype field tests is highly specific and is used to finalize many details of the intervention materials, including wording, core messages, colors, images and flow. Some prototypes are rejected at Step 6, necessitating a return to Step 3; others require more than one field test before progressing to Step 7.

Step 7: add professional illustrations and graphic design

After all content modifications are made to the prototype materials, a professional illustrator and graphic designer are hired to create ‘production-ready’ versions of the intervention materials. All materials are branded with graphic design features that engender project recognition and coherence among program activities and support materials. Child-oriented graphic design is used to increase the visual appeal of the intervention materials and to delineate discrete activities. For example, the Smoke-free Kids intervention uses a set of Smoke-Free Friends—comic strip characters of both genders and various ethnicities—to guide children through the program.

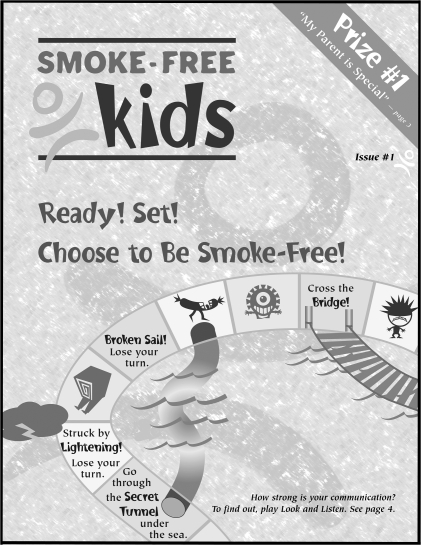

Step 8: produce intervention activity guides and supplemental materials

After Steps 1–7 are completed for all program activities, the activities are sorted into sets of six to eight, with attention to theme and logical sequencing, and then printed and bound in magazines called ‘activity guides’ (Fig. 4). The Smoke-free Kids intervention consists of five core activity guides, delivered at monthly intervals to 8- to 9-year-old children, and two booster guides, the first delivered at age 10 and the second delivered at age 11. As a series, the activity guides aim to achieve progressive development of anti-smoking socialization practices and norms. For example, activities are sequenced to gradually increase the skill and confidence of parents in communicating anti-smoking norms to children. Across all guides, repetition of activities and content is used to reinforce or broaden the application of key socialization skills. Repetition is particularly relevant to the booster guides, which engage parents and children in activities that reinforce participants’ tobacco-free skills, norms and commitments.

Fig. 4.

Smoke-free Kids activity guide cover page.

The fully produced Smoke-free Kids intervention includes the activity guides, support materials for specific activities (e.g. reporter's notebooks and press badges, Smoke-free Kids pencils, prize entry sheets, invitations for the child's ‘smoke-free celebration’, etc.) and also parent-only materials (e.g. tip sheets) used to deliver some of the parenting skills development program content. The intervention also includes small participation incentives (e.g. yo-yo's with the project logo) sent to all children who complete a specific activity in each guide.

Experiential learning—key to effective parenting interventions

We generally describe our approach to intervention as ‘print interactive’. This is an apt description because program participants do not simply read and ponder information provided by the intervention team nor do they receive behavioral recommendations without also receiving tools that will engage them directly in following through on those recommendations. In brief, we rely on experiential learning to make print-based materials highly interactive for parent and child participants.

This emphasis on experiential learning is a key aspect of our parenting programs, one we believe is critical to fostering parent–child capacity to gain experience with recommended anti-smoking practices. The program activities we develop using our eight-step approach involve parents and children in carefully structured experiences that, when completed, accomplish the specified program objective. Through the process of participating in the intervention itself, the learners practice the skills and have opportunities to reflect on the content. Materials are directed toward the cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains, and, because activities involve images, talking and movement/action, they are suitable for various learning styles. This experiential learning approach to intervention design is derived from the techniques and principles of dialogue education [39].

The best way to understand how to embed experiential learning in a print-based intervention is to examine some program components that provide clear examples. The following examples from the Smoke-free Kids program use various experiential methods, each targeting a specific intervention objective from Table I. Our method is contrasted with the widely used information-only approach to parenting education.

Objective: parents and children will discuss smoking-specific family values and expectations

Informational approach

Parents are given written recommendations, such as ‘state your own values clearly’ or ‘tell your child that you will be disappointed if they smoke’. Parents may be given some additional ideas of specific statements they can make to their child.

Experiential method

Why doesn't your parent want you to smoke? (Fig. 5) is an activity in which we engage children as ‘junior reporters’ (by sending them a press kit containing a reporter's notebook, a press badge and a pencil) and provide (in an activity guide that is used jointly by parent and child) scripted reporters’ interviews designed to elicit parents’ values and expectations about tobacco use. The activity does not require parents to remember text they have read and use it at some later date; instead, the activity provides parents with specific suggestions for responding to child questions about smoking, and then, the interview proper obliges both the parent and the child to enter into each discussion topic together.

Fig. 5.

Smoke-Free Kids activity: Why doesn't your parent want you to smoke?

Objective: parents and children will counter the pro-smoking images and messages in movies, print ads and other media

Informational approach

Parents are given information stating ‘Show your child how cigarette ads and images are designed to manipulate them into thinking that smoking is glamorous and cool’.

Experiential method

You'll be cool if you don't get fooled (Fig. 6) is a lift-the-flap activity that involves children and parents in debunking tobacco ads using photos of actual advertisements and specific questions about the ads and then engages them in guided discussions about techniques used by advertisers to promote tobacco.

Fig. 6.

Smoke-Free Kids activity: You'll be cool if you don't get fooled.

Objective: children will practice managing pro-smoking influences from peers

Informational approach

Parents are given written information about the reasons children experience peer pressure and the effects of peer pressure on children. They are told to get to know the child's friends and are given some scripts to share with the child about ways to say ‘no’.

Experiential method

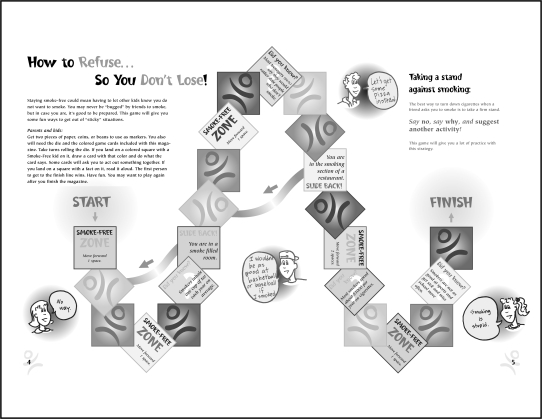

How to refuse so you don't lose (Fig. 7) is a parent–child role-play board game that teaches recognition of peer influence methods and rehearses refusal skills. In the game, parents use game cards to play various roles of peers offering puffs of cigarettes or promoting other pro-smoking actions. Children practice context-specific refusal skills, again guided by game materials; they also have opportunities to formulate their own reasons for and methods of refusing peer influence attempts. A reverse role-play component of the game facilitates parent modeling of the targeted skills.

Fig. 7.

Smoke-Free Kids activity: How to refuse so you don't lose.

Objective: parents and children will establish a social contract that specifies that the children will avoid any contact with or use of cigarettes and that parents will value children's smoke-free status

Informational approach

Parents are given information that states ‘Set consequences for smoking, and follow through on them’.

Experiential method

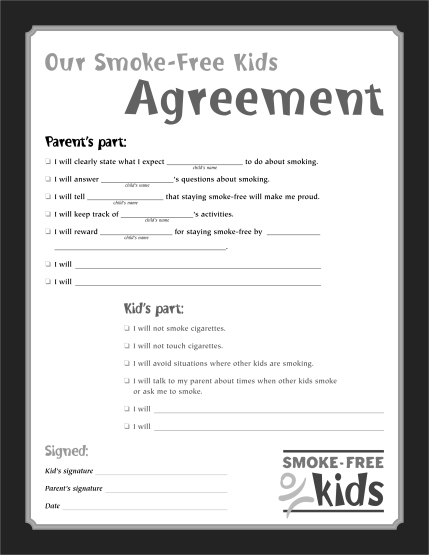

Smoke-free Kids includes a social contract tool called our Smoke-free Kids agreement (Fig. 8). The tool specifies the responsibilities of both parents and children and covers monitoring and rewarding children for staying smoke free (parents), avoidance of cigarettes and situations where other children are smoking (children) and communication (parents and children). It also allows parents and children to generate their own points of agreement.

Fig. 8.

Smoke-Free Kids activity: Our Smoke-Free Kids agreement.

Experiential learning is particularly useful for parenting programs because it provides the context most parents need to successfully engage their children in the intervention. Games, role-plays, scavenger hunts, hidden picture activities, lift-the-flap activities, poster contests and other types of activities use play, competition and curiosity to involve children easily. Post-intervention surveys with Smoke-free Kids participants indicated that these methods raised children's enthusiasm for the program. In fact, in many cases, parents reported that their children encouraged the parent to participate as each monthly activity guide was received. Successful engagement of children also means that children feel that they are partners in rather than receivers of the intervention. This partnership orientation can strengthen program effects because children will have had a role in articulating and reinforcing anti-smoking norms for their families.

Conclusions

Given the known effects of child-rearing practices on initiation of smoking and other child health risk behaviors [1–10], parenting programs ought to be a primary strategy for child health promotion in multiple areas of public health practice. This program article aims to support this recommendation by contributing a systematic theory-based approach to developing parenting programs for child health promotion.

Funding

National Cancer Institute (RO1 CA106316).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ameena Batada, Jennifer Hudman, Kristen Smith, Sarah Thach and Gambrill Hollister Wagner for their contributions to the development of the Smoke-free Kids intervention.

References

- 1.Otten R, Engels R, van den Eijnden R. General parenting, anti-smoking socialization, and smoking onset. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:859–69. doi: 10.1093/her/cym073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chassin L, Presson CC, Rose J, et al. Parenting style and smoking-specific parenting practices as predictors of adolescent smoking onset. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:333–44. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson C, Henriksen L, Dickinson D. Alcohol-specific socialization, parenting behaviors and alcohol use by children. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:362–7. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders MR. Community-based parenting and family support interventions and the prevention of drug abuse. Addict Behav. 2000;25:929–42. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson C, Foshee VA. Violence-related behaviors among adolescents: relations with responsive and demanding parenting. J Adolesc Res. 1998;11:343–59. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes SO, Power TG, Fisher JO, et al. Revisiting a neglected construct: parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite. 2005;44:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kremers SP, Brug J, DeVries H, et al. Parenting style and adolescent fruit consumption. Appetite. 2003;41:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(03)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davison KK, Cutting TM, Birch LL. Parents’ activity-related parenting practices predict girls’ physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1589–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000084524.19408.0C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartos J, Eitel P, Simons-Morton B. Parenting practices and adolescent risky driving: a three-month prospective study. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:194–206. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartos JL, Eitel P, Haynie DL, et al. Can I take the car? Relations among parenting practices and adolescent problem-driving practices. J Adolesc Res. 2000;15:352–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson C, Bee-Gates DJ, Henriksen L. Authoritative parenting, child competencies, and initiation of cigarette smoking. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:103–16. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson C, Henriksen L. Do as I say: parent smoking, anti-smoking socialization, and smoking onset among children. Addict Behav. 1997;22:107–14. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson C, Henriksen L, Dickinson D, et al. The early use of alcohol and tobacco: its relation to children's competence and parents’ behavior. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:359–64. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The authoritative parenting index: predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25:319–37. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson C. Cognitive susceptibility to smoking and initiation of smoking during childhood: a longitudinal study. Prev Med. 1998;27:129–34. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson C, Dickinson D. Can parents who smoke socialise their children against smoking? Results from the Smoke-free Kids intervention trial. Tob Control. 2003;12:52–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson C, Dickinson D. Enabling parents who smoke to prevent their children from initiating smoking: results from a three-year intervention evaluation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:56–62. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clausen JA. Family structure, socialization, and personality. In: Hoffman LW, Hoffman ML, editors. Review of Child Development Research. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1966. pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clausen JA. Perspectives on childhood socialization. In: Clausen JA, editor. Socialization and Society. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.; 1968. pp. 131–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maccoby EE, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development. New York: John Wiley; 1983. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartup WW. Peer relations. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1983. pp. 116–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith MB. Competence and socialization. In: Clausen JA, editor. Socialization and Society. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co.; 1968. pp. 271–320. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cialdini RB, Trost MR. Social influence: social norms, conformity and compliance. In: Gilbert DT, Fisk ST, Lindzey G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 151–92. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MJ. Persuasion and Human Action: A Review and Critique of Social Influence Theories. Belmont, CA: Wadswort; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maccoby EE. The role of parents in the socialization of children: an historical overview. Dev Psychol. 1992;28:1006–17. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Child Dev. 1993;113:487–96. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J Early Adolesc. 1991;11:56–95. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumrind D. New directions in socialization research. Am Psychol. 1980;35:639–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman PH, et al. The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Dev. 1987;58:1244–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Darling N, et al. Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 1994;65:754–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smetana JG, Asquith P. Adolescents’ and parents’ conceptions of parental authority and personal autonomy. Child Dev. 1994;65:1147–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumrind D. Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children. Youth Soc. 1978;9:239–75. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg L, Elmen JD, Mounts NS. Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success among adolescents. Child Dev. 1989;60:1424–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baumrind D. Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Dev. 1966;37:887–907. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grolnick WS, Ryan RM. Parent styles associated with children's self-regulation and competence in school. J Educ Psychol. 1989;81:143–54. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumrind D. Rearing competent children. In: Damon W, editor. Child Development Today and Tomorrow. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1989. pp. 349–78. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radziszewska B, Richardson JL, Dent CW, et al. Parenting style and adolescent depressive symptoms, smoking, and academic achievement: ethnic, gender, and SES differences. J Behav Med. 1996;19:289–305. doi: 10.1007/BF01857770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Byrne KK, Haddock CK, Poston WSC. Parenting style and adolescent smoking. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:418–25. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vella J. Learning to Listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]