Abstract

Peer victimization experiences represent developmentally salient stressors among adolescents and are associated with the development of internalizing symptoms. However, the mechanisms linking peer victimization to adolescent psychopathology remain inadequately understood. This study examined emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer stress to changes in internalizing symptoms among adolescents in a longitudinal design. Peer victimization was assessed in a large (N = 1,065) racially diverse (86.6% non-White) sample of adolescents ages 11 to 14 using the Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire. Emotion dysregulation and symptoms of depression and anxiety were also assessed. Structural equation modeling was used to create a latent construct of emotion dysregulation from measures of discrete emotion processes and of peer victimization and internalizing symptoms. Peer victimization was associated with increased emotion dysregulation over a 4-month period. Increases in emotion dysregulation mediated the relationship between relational and reputational, but not overt, victimization and changes in internalizing symptoms over a 7-month period. Evidence for a reciprocal relationship between internalizing symptoms and relational victimization was found, but emotion dysregulation did not mediate this relationship. The implications for preventive interventions are discussed.

Keywords: peer victimization, emotion regulation, depression, anxiety, internalizing symptoms

The deleterious effects of stress on physical and mental health have been consistently documented (Brown, 1993; Dohrenwend, 1998; Kessler, 1997). A well-developed literature has identified the negative physiological effects of stress, particularly dysregulation in the neuroendocrine and immune systems, that represent biological mechanisms linking stress to disease (Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004). The psychological mechanisms underlying the association between stress and poor mental health outcomes are less well understood. In the current study, we examine the role of emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking stress to internalizing symptoms among adolescents.

Adolescence represents an important period in which to examine mechanisms linking stress to the development of psychopathology. Changes in social systems (Collins, 1990, 2003; Larson & Richards, 1991) along with the biological and cognitive changes of adolescence present innumerable affectively-laden situations in which stress must be successfully managed to ensure adaptive functioning. Given the myriad of changes occurring during this time period, it is not surprising that adolescence is associated with greater amounts of negative affect and perceived stress than late childhood (Larson & Ham, 1993; Larson & Lampman-Petraitis, 1989) and is characterized by high risk for the development of psychopathology (Hankin et al., 1998; Lewinsohn, Striegel-Moore, & Seeley, 2000). Stressful events become more closely linked to the emergence of negative affect during this period, rendering adolescents more emotionally vulnerable to the effects of stress (Larson & Ham, 1993; Larson, Moneta, Richards, & Wilson, 2002).

Peer victimization, or being the target of aggression by peers, represents a developmentally salient stressor for adolescents. Peer victimization occurs frequently in adolescent peer relationships and has damaging effects on social and psychological adjustment (Olweus, 1993; Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001). Peer victimization has been associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression in both cross-sectional (Hawker & Boulton, 2000) and longitudinal studies (Storch, Masia-Warner, Crisp, & Klein, 2005; Vernberg, Abwender, Ewell, & Beery, 1992) and predicts increased incidence of internalizing and externalizing disorders (Coie, Lochman, Terry, & Hyman, 1992). Childhood peer victimization is also associated with anxiety and depression in adulthood (Gladstone, Parker, & Malhi, 2006; Olweus, 1993), rendering these stress experiences particularly damaging. Two separate, but related, types of peer victimization have been identified in the literature. Both overt victimization, or being the target of physical aggression, threats, or verbal aggression (Prinstein et al., 2001; Vernberg, 1990), and relational victimization, in which relationship status is used as the mechanism of aggression through social exclusion, gossip, or other means (Crick & Bigbee, 1998; LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; Prinstein et al., 2001), have been demonstrated to predict internalizing symptoms and psychological distress among youth.

Identifying mechanisms linking stress and peer victimization to negative mental health outcomes among adolescents is essential in order to develop effective, theory-based preventive interventions targeting those processes that lead from stress to psychopathology. One influential model has proposed that chronic stress leads to negative health outcomes through psychological pathways involving poor social competence and emotion dysregulation (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002). Attempts to identify mechanisms linking peer victimization to psychopathology outcomes have largely focused on social-cognitive processes (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990), consistent with the social competence mechanism in Repetti and colleagues’ (2002) model. Disruptions in social information processing, such as increased attention to hostile cues, have been found to mediate the relationship between peer victimization and aggressive behavior (Dodge et al., 2003). In contrast, peer victimization leads to increased depressive symptoms primarily among youth with a depressogenic and self-critical attributional style (Prinstein & Aikins, 2004; Prinstein, Cheah, & Guyer, 2005), suggesting a role for a negative information-processing style as a moderator, not a mediator, of the association between victimization and internalizing symptoms. Indeed, social competence has not been found to mediate the association between peer victimization and adolescent depressive symptoms (LaGreca & Harrison, 2005).

Emotion dysregulation, the second putative mediator in the Repetti and colleagues’ (2002) model, represents a potential mechanism responsible for the association between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms. Emotion regulation deficits are increasingly understood as important predictors of internalizing psychopathology among adolescents. Deficits in emotional understanding and ability to manage negative affect have been reported in youth with symptoms of both anxiety and depression (Abela, Brozina, & Haigh, 2002; Garber, Braafladt, & Weiss, 1995; Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000; Suveg & Zeman, 2004). For example, depressed youth are more likely to engage in ruminative responses to distress (Abela et al., 2002; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003) that are likely to prolong negative affect and reduce effective problem-solving (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson, 1993). Deficits in the ability to manage other negative emotions, such as anger, have also been documented in youth with internalizing symptomatology (Zeman, Shipman, & Suveg, 2002).

Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that emotion regulation may account for the relationship between peer victimization and adolescent psychopathology. Chronic stress during childhood and adolescence leads to deficits in emotion regulation (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; Repetti et al., 2002). In addition, both social exclusion (Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Twenge, 2005) and stigma (Inzlicht, McKay, & Aronson, 2006)—two constructs that are conceptually similar to peer victimization—have been shown to be ego depleting, whereby exerting self-control in one domain consumes regulatory resources that are needed for future tasks in other domains (Inzlicht et al., 2006), providing support for the link between specific stressors and subsequent deficits in emotion regulation. Similarly, peer victimization experiences elicit negative emotions including anger, sadness, and contempt (Mahady Wilton, Craig, & Pepler, 2000), and youth who are the victims of peer aggression exhibit high levels of emotional arousal and reactivity (Schwartz, Dodge, & Coie, 1993). Over time, the effort required to manage the increased arousal and negative affect associated with victimization experiences may eventually diminish individuals’ coping resources and therefore their ability to understand and adaptively manage their emotions, leaving them more vulnerable to adverse mental health outcomes. Although there is theoretical support for emotion dysregulation as a mediator of the association between peer victimization and psychopathology, to our knowledge no empirical studies have examined this association directly.

Importantly, the relationships between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms are likely reciprocal in nature. Although victimization experiences lead to increases in symptomatology over time, adolescents who are depressed or anxious are also more likely to be victimized by their peers than youth who do not have internalizing symptoms (Hodges & Perry, 1999; Vernberg, 1990). Adolescents with internalizing symptoms may be less able to assert or defend themselves in interactions with aggressive peers, thus reinforcing aggressive behavior (Hodges & Perry, 1999), or may lack friendships that could deter aggressive behavior from peers. Given that emotion dysregulation has been linked to poor social functioning and peer rejection among youth (Eisenberg et al., 1995; Losoya, Eisenberg, & Fabes, 1998), it may also play a role in explaining the association between internalizing symptoms and subsequent victimization. To date, however, the role of emotion dysregulation in explaining the reciprocal relationships between internalizing symptoms and peer victimization has yet to be examined in the literature.

The purpose of the current investigation was therefore to address these gaps in the literature using prospective data from a large, diverse community-based sample of adolescents. We first examined the role of emotion dysregulation as a mediator of the association between peer victimization and changes in internalizing symptoms over time. We hypothesized that peer victimization would lead to subsequent increases in emotion dysregulation and in symptoms of depression and anxiety. Further, we predicted that emotion dysregulation would mediate the association between peer victimization and changes in symptomatology over time. To test this hypothesis, we examined baseline peer victimization as a predictor of increased emotion dysregulation over 4 months, a standard time interval in which to examine changes in psychological traits as a result of stressors (Brown & Harris, 1989). Changes in emotion dysregulation were then examined as mediators of the association between peer victimization and internalizing symptom development over 7 months following the baseline assessment. A similar length of follow-up has been used in prior research examining the effects of peer victimization on internalizing symptoms among adolescents (Vernberg, 1990; Vernberg et al., 1992). We also hypothesized that youth with internalizing symptoms would be more likely to be victimized by their peers, suggesting reciprocal relationships between peer victimization and symptoms of depression and anxiety. We examined emotion dysregulation as a mediator of this longitudinal association using the mediation approach described above. Importantly, we were able to apply a powerful test of mediation in this study using a longitudinal design with three separate assessments (Maxwell & Cole, 2007).

Method

Participants

The sample for this study was recruited from the total enrollment of two middle schools (Grades 6–8) in central Connecticut that agreed to participate in the study (students in self-contained special education classrooms and technical programs who did not attend school for the majority of the school day were excluded). The community in which the schools are located is a small urban community (metropolitan population of 71,538). Schools were chosen for the study based on the demographic characteristics of the school district and their willingness to participate.

The parents of all eligible children (N = 1567) in the participating middle schools were asked to provide active consent for their children to participate in the study. Parents who did not return written consent forms to the school were contacted by telephone. Twenty-two percent of parents did not return consent forms and could not be reached to obtain consent, and 6% of parents declined to provide consent. The overall participation rate in the study at baseline was 72%. Of participants who were present at baseline, 221 (20.8%) did not participate at the Time 2 assessment, and 217 (20.4%) did not participate at the Time 3 assessment, largely due to transient student enrollment in this district. Data from the school district indicate that over the 4-year period from 2000–2004, 22.7% of students had left the district (Connecticut Department of Education, 2006). Analyses were conducted using the sample of 1,065 participants who were present at the baseline assessment, excluding participants who were present at Time 2 and/or Time 3 but not at Time 1.

The baseline sample included 51.2% (N = 545) boys and 48.8% (N = 520) girls. Participants were evenly distributed across grade level. The race/ethnicity composition of the sample was as follows: 13.2% (N = 141) non-Hispanic White, 11.8% (N = 126) non-Hispanic Black, 56.9% (N = 610) Hispanic/Latino, 2.2% (N = 24) Asian/Pacific Islander, 0.2% (N = 2) Native American, 0.8% (N = 9) Middle Eastern, 9.3% (N = 100) Biracial/Multiracial and 4.2% (N = 45) Other racial/ethnic groups. Twenty-seven percent (N = 293) of participants reported living in single-parent households. The community in which the participating middle schools reside is uniformly lower SES, with a per capita income of $18,404 (Connecticut State Department of Education, 2005 based on data from 2001). School records indicated that 62.3% of students qualified for free or reduced lunch in the 2004–2005 school year. There were no differences across the two schools in demographic variables.

Measures

Internalizing symptoms and emotion dysregulation were each assessed with multiple measures. Internalizing symptoms were assessed using measures of both depression and anxiety. Poor emotional understanding, dysregulated expression of anger and sadness, and rumination were assessed as indicators of emotion dysregulation.

Peer Victimization

The Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (RPEQ; Prinstein et al., 2001) was used to assess participants’ peer victimization experiences. The RPEQ was developed from the Peer Experiences Questionnaire (Vernberg, Jacobs, & Hershberger, 1999) and assesses overt, relational, and reputational victimization by peers. The questionnaire includes 18 items that ask participants to rate how often an aggressive behavior was directed towards them in the past year on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never (1) to a few times a week (5). The original and revised measure has demonstrated good test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and convergent validity (Prinstein et al., 2001; Vernberg, Fonagy, & Twemlow, 2000). The RPEQ assesses each of the following forms of victimization: overt (e.g., “A kid threatened to hurt or beat me up”); relational (“To get back at me, another kid told me that he or she would not be my friend”); and reputational (“A kid gossiped about me so that others would not like me.”). Scores are obtained by summing the items within each subscale. The overt victimization subscale includes 4 items for scores ranging from 4 to 20, the relational victimization subscale includes 5 items for scores ranging from 5 to 25, and the reputational victimization subscale includes 3 items for scores ranging from 3 to 15. Each of the RPEQ victimization subscales demonstrated adequate internal consistency in this sample: overt (α = 0.78); relational (α = 0.79); reputational (α = 0.79).

Depressive Symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) is a widely used self-report measure of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. The CDI includes 27 items consisting of three statements (e.g., I am sad once in a while, I am sad many times, I am sad all the time) representing different levels of severity of a specific symptom of depression. The CDI has sound psychometric properties, including internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and discriminant validity (Kovacs, 1992; Reynolds, 1994). The item pertaining to suicidal ideation was removed from the measure at the request of school officials and the human subjects committee. The 26 remaining items were summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 52. The CDI demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .82).

Anxiety Symptoms

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) is a 39-item widely used measure of anxiety in children. The MASC assesses physical symptoms of anxiety, harm avoidance, social anxiety, and separation anxiety and is appropriate for children ages 8 to 19. Each item presents a symptom of anxiety, and participants indicate how true each item is for them on a four-point Likert scale ranging from never true (0) to very true (3). A total score, ranging from 0 to 117, is generated by summing all items. The MASC has high internal consistency and test-retest reliability across 3-month intervals, and established convergent and divergent validity (Muris, Merckelbach, Ollendick, King, & Bogie, 2002). The MASC demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = 0.88).

Poor Emotional Understanding

Emotional understanding was assessed using an 8-item subscale from the Emotion Expression Scale for Children (EESC; Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002) that provides statements involving lack of emotional awareness and understanding. Children respond to items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from not at all true (1) to extremely true (5). The 8 items are summed to generate a total score ranging from 8 to 40. Higher scores on this subscale reflect lack of emotional understanding. Representative items from this scale are, “I have feelings that I can’t figure out” and “I often do not know how I am feeling.” The EESC has high internal consistency and moderate test-retest reliability, and the construct validity of the measure has been established (Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). This scale has been used with early adolescents (Sim & Zeman, 2005, 2006). This subscale demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .82).

Dysregulated Emotion Expression

The Children’s Sadness Management Scale (CSMS) and Anger Management Scale (CAMS) assess both adaptive and maladaptive aspects of emotion expression and regulation for the specific emotions of sadness and anger (Zeman, Shipman, & Penza-Clyve, 2001). We used the Dysregulation subscale of each of these measures, which assesses the extent to which children engage in maladaptive or inappropriate expressions of emotion, such as excessive crying. Higher scores on this scale reflect higher levels of emotion dysregulation. The CSMS contains 12 items, and the CAMS contains 11 items. Children respond on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from hardly ever (1) to often (3). The Dysregulation scale for each measure contains 3 items that are summed to create scores ranging from 3 to 9. The scales have demonstrated adequate reliability, and their construct validity has been established (Zeman et al., 2001). These scales have been used in prior research with early adolescents (Sim & Zeman, 2005, 2006). Representative items from the dysregulation scale are, “I attack whatever it is that is making me angry,” (CAMS) and “I cry and carry on when I’m sad” (CSMS). The Dysregulation subscale of the CSMS (α =0.60) and CAMS (α =0.66) each demonstrated adequate reliability.

Rumination

The Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela et al., 2002) is a 25-item scale that assesses the extent to which children respond to sad feelings with rumination, defined as self-focused thought concerning the causes and consequences of depressed mood, distraction, or problem-solving. The measure is modeled after the Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) that was developed for adults. For each item, youth are asked to rate how often they respond in that way when they feel sad on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from almost never (1) to almost always (4). The rumination subscale includes 13 items that are summed to generate a score ranging from 13 to 42. Sample items include: “Think about a recent situation wishing it had gone better” and “Think why can’t I handle things better?” The reliability and validity of the CRSQ have been demonstrated in samples of early adolescents (Abela et al., 2002). The CRSQ rumination scale demonstrated good reliability in this study (α = 0.86).

Procedure

Participants completed study questionnaires during their homeroom period. All questionnaires used in the present analyses were administered at Time 1 and Time 3, and the emotion dysregulation measures were additionally administered at Time 2. Four months elapsed between the Time 1 (November 2005) and Time 2 (March 2006) assessments, and three months elapsed between Time 2 and Time 3 (June 2006) assessments. This time frame was chosen to allow the maximum time between assessments to observe changes in internalizing symptoms while also ensuring that all assessments occurred within the same academic year to avoid high attrition. Given time constraints imposed by the school, we were only able to assess potential mediators at Time 2 whereas all study measures were administered at Times 1 and 3. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of their participation.

Data Analytic Plan

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to perform the mediation analyses using AMOS 6.0 software (Arbuckle, 2005). Analyses were conducted using the full information maximum likelihood estimation method, which estimates means and intercepts to handle missing data. A latent variable representing emotion dysregulation was created using the observed variables of poor emotional awareness, dysregulated expression of anger and of sadness, and rumination. Multiply indicated latent variables were created for both peer victimization and internalizing symptoms using parcels of items from the relevant scales. Parcels were created using the domain representative approach, which accounts for the multidimensionality of these outcomes (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002), such that each parcel included items from each of the subscales of the relevant measures. In SEM, the use of parcels to model constructs as latent factors, as opposed to an observed variable representing a total scale score, confers a number of psychometric advantages including greater reliability, reduction of error variance, and increased efficiency (Kishton & Wadaman, 1994; Little et al., 2002).

After testing the measurement models for all constructs, the mediation analyses proceeded as follows: Time 1 peer victimization was examined as a predictor of emotion regulation deficits at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 emotion dysregulation. Emotion regulation deficits at Time 2 were then evaluated as predictors of internalizing symptoms at Time 3, controlling for Time 1 symptoms. The full mediation model was examined using the product of coefficients method to evaluate the hypothesis that emotion regulation deficits mediate the longitudinal relationship between peer victimization and internalizing symptomatology. Sobel’s standard error approximation was used to test the significance of the intervening variable effect (Sobel, 1982). The product of coefficients approach is associated with low bias and Type 1 error rate, accurate standard errors, and adequate power to detect small effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). The mediation model was then examined for overt, relational, and reputational victimization separately to determine whether mediation effects were consistent across subtypes of victimization. Only participants who were present at baseline (N = 1,065) were included in mediation analyses.

An alternative model of directionality was then examined in which the longitudinal association between Time 1 internalizing symptoms and Time 3 peer victimization was mediated by emotion regulation deficits. Analyses proceeded in the same manner as the previous mediation analyses. Finally, we examined the role of gender as a moderating variable. Multi-group analyses were conducted to examine whether the process of mediation was moderated by gender. Each of the mediation paths was constrained to be equal for males and females, and the difference in model fit was examined using a chi-square test.

Results

Attrition

Analyses were first conducted to determine whether participants who did not complete all three assessments differed from those who completed the baseline and two follow-up assessments. Univariate ANOVAs were conducted for continuous outcomes with attrition as a between-subjects factor. Chi-square analyses were performed for dichotomous outcomes. These analyses revealed that participants who completed the baseline but not both follow-up assessments were more likely to be female, χ2(1) = 6.85, p < 0.01, but did not differ in grade level, race/ethnicity, or being from a single parent household (p-values > 0.10). Participants who did not complete at least one of the follow-up assessments did not differ from participants who completed all three assessments on baseline depression or anxiety symptoms, levels of peer victimization, emotional awareness, dysregulated sadness, dysregulated anger, or rumination (all p-values > 0.10).

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays the mean and standard deviation of all measures at each time point by gender. The means in this sample are similar to values obtained in other samples of early adolescents (i.e., within 1 standard deviation). Means for dysregulated negative emotion, depression, and anxiety in the present sample are consistent with those reported in other samples (Muris et al., 2002; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002; Zeman et al., 2001). Means for overt and relational victimization, as well as poor emotional awareness, are slightly higher but within the average range reported in other samples (LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). Rumination scores in the present sample are slightly lower but within the average range reported in a sample of 7th graders (Abela et al., 2002). Table 2 provides the zero-order correlations among all study measures. As expected, peer victimization was positively associated with emotion dysregulation and internalizing symptoms, which were positively associated with one another.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of peer victimization, emotion regulation, and symptom measures by gender.

| Measure | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | |||

| RPEQ – Overt Victimization | 7.43(3.30) | 6.73(3.14) | 7.07(3.24) |

| RPEQ – Relational Victimization | 9.14(3.31) | 9.24(3.57) | 9.21(3.56) |

| RPEQ – Reputational Victimization | 5.69(2.84) | 5.66(2.80) | 5.73(2.84) |

| EESC – Poor Emotional Awareness | 17.98(6.51) | 19.13(7.17) | 18.67(7.02) |

| CSMS – Dysregulated Sadness | 4.35(1.38) | 4.96(1.54) | 4.71(1.50) |

| CAMS – Dysregulated Anger | 5.51(1.74) | 5.28(1.60) | 5.43(1.63) |

| CRSQ – Rumination | 9.33(7.40) | 12.31(8.05) | 10.94(7.65) |

| CDI – Depression | 8.50(5.99) | 9.62(6.40) | 9.67(6.44) |

| MASC – Anxiety | 35.90(14.56) | 43.03(14.70) | 40.19(15.39) |

| Time 2 | |||

| EESC – Poor Emotional Awareness | 19.17(6.43) | 20.88(7.35) | 19.81(6.79) |

| CSMS – Dysregulated Sadness | 4.31(1.33) | 4.95(1.40) | 4.66(1.65) |

| CAMS – Dysregulated Anger | 5.44(1.63) | 5.55(1.55) | 5.53(1.64) |

| CRSQ – Rumination | 8.67(6.27) | 12.16(8.43) | 10.84(7.65) |

| Time 3 | |||

| RPEQ – Overt Victimization | 7.22(3.49) | 6.87(2.98) | 7.07(3.28) |

| RPEQ – Relational Victimization | 8.83(4.06) | 9.55(3.67) | 9.17(3.82) |

| RPEQ – Reputational Victimization | 5.44(2.83) | 6.05(2.68) | 5.77(2.79) |

| EESC – Poor Emotional Awareness | 17.41(7.49) | 18.84(7.19) | 18.40(7.47) |

| CSMS – Dysregulated Sadness | 4.50(1.50) | 5.03(1.50) | 4.79(1.53) |

| CAMS – Dysregulated Anger | 5.29(1.81) | 5.66(1.71) | 5.52(1.73) |

| CRSQ – Rumination | 7.55(6.73) | 11.57(8.57) | 10.18(8.07) |

| CDI – Depression | 9.70(8.18) | 10.73(7.74) | 10.63(8.15) |

| MASC – Anxiety | 30.32(16.70) | 37.28(17.16) | 34.80(18.05) |

Note: Higher scores on emotion regulation measures indicate higher levels of emotion dysregulation; RPEQ = Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire; EESC = Emotion Expression Scale for Children; CSMS = Children’s Sadness Management Scale; CAMS = Children’s Anger Management Scale; CRSQ = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children.

Table 2.

Correlations between peer victimization, symptoms, and emotion regulation characteristics.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RPEQ Overt Victimization T1 |

— | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. RPEQ Relational Victimization T1 |

.67** | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. RPEQ Reputational Victimization T1 |

.66** | .63** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 4. CDI Depression T1 |

.31** | .32** | .27** | — | ||||||||||||||

| 5. MASC Anxiety T1 |

.30** | .34** | .26** | .28** | — | |||||||||||||

| 6. EESC — Poor Emotional Awareness T1 |

.31** | .38** | .32** | .40** | .42** | — | ||||||||||||

| 7. CSMS Dysregulated Sadness T1 |

.19** | .25** | .19** | .21** | .31** | .30** | — | |||||||||||

| 8. CAMS Dysregulated Anger T1 |

.11** | .13** | .10** | .25** | .01 | .19** | .20** | — | ||||||||||

| 9. CRSQ Rumination T1 |

.28** | .37** | .29** | .42** | .55** | .56** | .35** | .16** | — | |||||||||

| 10. EESC — Poor Emotional Awareness T2 |

.18** | .29** | .22** | .35** | .33** | .48** | .20** | .16** | .36** | — | ||||||||

| 11. CSMS Dysregulated Sadness T2 |

.12** | .17** | .11** | .15** | .17** | .18** | .29** | .07 | .21** | .30** | — | |||||||

| 12. CAMS Dysregulated Anger T2 |

.13** | .14** | .16** | .19** | .09* | .18** | .14** | .38** | .17** | .23** | .19** | — | ||||||

| 13. CRSQ Rumination T2 |

.23** | .29** | .29** | .39** | .43** | .43** | .29** | .08* | .57** | .51** | .34** | .24** | — | |||||

| 14. RPEQ Overt Victimization T3 |

.41** | .34** | .32** | .18** | .16** | .19** | .11** | .14** | .21** | .25** | .17** | .17** | .24** | — | ||||

| 15. RPEQ Relational Victimization T3 |

.28** | .39** | .29** | .19** | .26** | .20** | .14** | .09* | .29** | .29** | .21** | .18** | .30** | .71** | — | |||

| 16. RPEQ Reputational Victimization T3 |

.25** | .31** | .35** | .20** | .16** | .18** | .13** | .13** | .25** | .26** | .18** | .15** | .28** | .72** | .72** | — | ||

| 17. CDI Depression T3 |

.25** | .32** | .21** | .54** | .13** | .23** | .17** | .24** | .23** | .30** | .17** | .24** | .33** | .23** | .22** | .21** | — | |

| 18. MASC Anxiety T3 |

.25** | .34** | .25** | .24** | .53** | .31* | .25** | .02 | .35** | .36** | .28** | .10** | .44** | .29** | .37** | .28** | .33** | — |

Note: Correlations are reported for peer victimization at Time 1 and Time 3, emotion regulation deficits at Time 1 and Time 2, and symptoms at Time 1 and Time 3; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; RPEQ = Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire; EESC = Emotion Expression Scale for Children; CSMS = Children’s Sadness Management Scale; CAMS = Children’s Anger Management Scale; CRSQ = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Measurement Models

The measurement model of emotion dysregulation was constructed using four indicator variables: poor emotional awareness, dysregulated expression of anger and of sadness, and ruminative responses to distress. For the hypothesized model, χ2(2) = 1.21, p = .299, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .01 (90% CI: .00–.06). Thus, all fit indices indicated that the measurement model of emotion dysregulation fit the data very well.

The measurement models for peer victimization and internalizing symptoms were each constructed from parcels of items created using the domain representative approach (Little et al., 2002), such that each parcel included items from each of the subscales of the relevant measures. The peer victimization model was created from three parcels, each including items reflecting overt, relational, and reputational victimization from the RPEQ, and fit the data well, χ2(1) = 22.57, p < .01, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .09 (90% CI: .06–.12). The internalizing symptoms model was created from four parcels, each of which included items from the CDI and each of the subscales of the MASC, and fit the data well, χ2(2) = 4.58, p = .01, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .05 (90% CI: .02– .08).

Mediation Analyses

Emotion dysregulation was examined as a mediator of the longitudinal relationship between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms. Time 1 peer victimization was associated with Time 2 emotion dysregulation, controlling for emotion dysregulation at Time 1, β = .11, p < .01. Time 2 emotion dysregulation was associated with Time 3 internalizing symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms, β = .36, p < .001. Time 1 internalizing symptoms were associated with nearly all Time 2 emotion dysregulation indicator variables in bivariate analyses (see Table 2). As such, a path from Time 1 internalizing symptoms to Time 2 emotion dysregulation was included in the final mediation model. The covariance between Time 1 internalizing symptoms and Time 1 emotion dysregulation was also modeled.

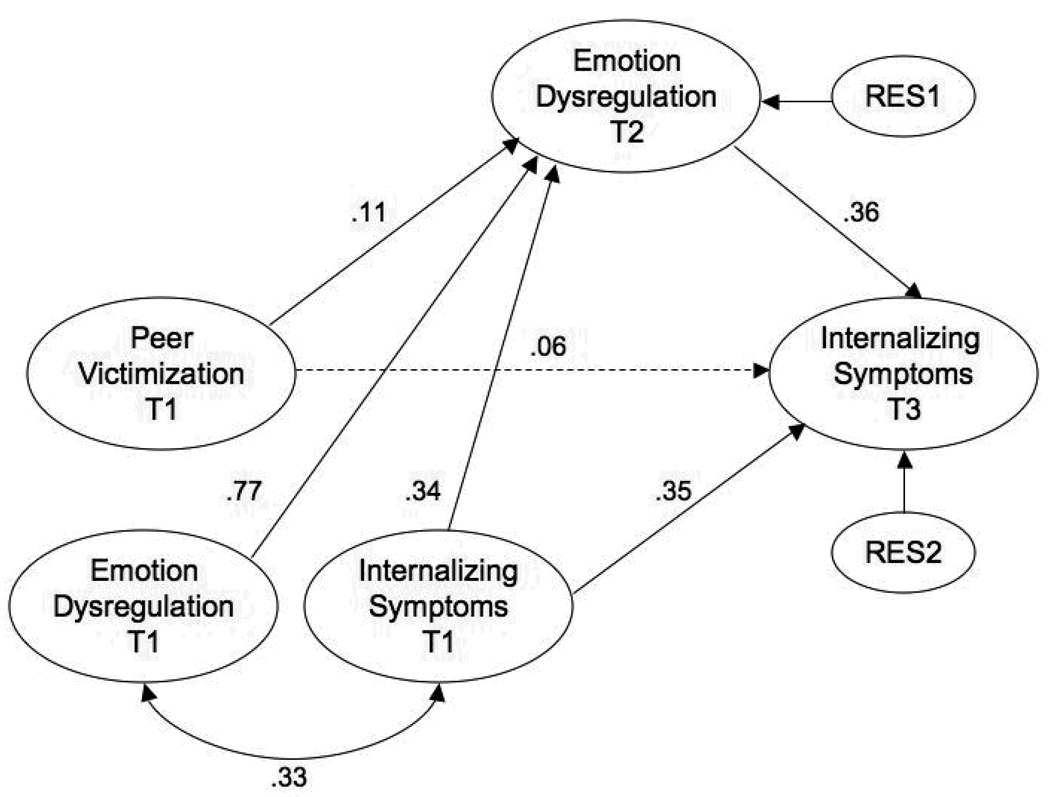

In the full mediation model, Time 1 peer victimization was no longer a significant predictor of Time 3 internalizing symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms and Time 1 emotion dysregulation, when Time 2 emotion dysregulation was added to the model, β = .06, p = .096 (see Figure 1). Sobel’s z-test revealed a significant indirect effect of peer victimization on internalizing symptoms through emotion dysregulation, z = 2.42, p = .016. All fit indices indicated that the model fit the data well: χ2(64) = 661.4, p < .001, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA = .05 (90% CI: .04–.05).

Figure 1.

Note. Figure represents final mediational model for internalizing symptoms. Numbers represent standardized path coefficients (β). All paths shown are significant (p < .05), except those drawn with broken lines. All constructs were modeled as latent variables. Due to space constraints, indicator variables are not displayed.

We next examined whether mediation effects were consistent across the three subtypes of peer victimization. In the final mediation model, a significant indirect effect for relational victimization, z = 3.08, p < .001, and reputational victimization, z = 3.06, p < .001, on internalizing symptoms was found through emotion dysregulation, but not for overt victimization, z = .95, p = .343. Both the relational, χ2(64) = 671.0, p < .001, CFI =.94, and RMSEA=.05 (90% CI: .04–.05), and reputational models, χ2(64) = 599.1, p < .001, CFI = .95, and RMSEA=.05 (90% CI: .04–.05), fit the data well.

Reciprocal Relationships

We next examined the longitudinal relationship between internalizing symptoms and peer victimization and the role of emotion dysregulation as a mediator of that relationship. Time 1 internalizing symptoms were not associated with Time 3 peer victimization, controlling for victimization at Time 1, β = .07, p = .132. When we examined the subtypes of victimization, internalizing symptoms marginally predicted relational, β = .11, p = .058, but not overt, β = −.01, p = .886, or reputational, β = .08, p = .132, victimization. Internalizing symptoms at Time 1 were not associated with Time 2 emotion dysregulation after controlling for Time 1 emotion dysregulation, β = .03, p = .720. Because internalizing symptoms did not longitudinally predict Time 2 emotion dysregulation, we did not examine the full mediation model. Thus, emotion dysregulation did not mediate the longitudinal association between internalizing symptoms and peer victimization.

Gender Effects

We examined whether the role of emotion dysregulation as a mediator of the relationship between relational and reputational victimization and subsequent internalizing symptoms was modified by gender. We did not examine overt victimization because emotion dysregulation did not mediate the association between overt victimization and internalizing symptoms. When the mediation paths of interest (See Figure 1) were constrained to equivalence across males and females, the model fit did not significantly worsen for relational, χ2(3) = 3.35, p = .34, or reputational, χ2(3) = 1.58, p = .66, victimization, indicating that the process and strength of mediation was consistent across gender.

Discussion

Given the high importance placed on peer relationships during adolescence (Larson & Richards, 1991), social rejection and victimization experiences during this period represent particularly salient stressors. The purpose of the current investigation was to examine the role of emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms among adolescents. As hypothesized, peer victimization was associated with increases in emotion dysregulation over time. This increased emotion dysregulation, in turn, accounted for the association between peer victimization and subsequent changes in symptoms in both male and female adolescents. The conceptualization of emotion dysregulation as a pathway linking peer victimization to psychopathology is consistent with prior theoretical work linking chronic stress to negative mental health outcomes (Repetti et al., 2002), as well as evidence suggesting that stressful life events and chronic stress associated with adverse rearing environments disrupt the adaptive processing of emotion (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; McLaughlin & Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

These findings extend the literature on peer victimization and psychopathology in several important ways. To our knowledge, this study is the first to document prospectively that peer victimization is associated with subsequent increases in emotion dysregulation among adolescents. These results suggest that the effort required to manage the negative emotions elicited by victimization experiences may deplete the resources necessary for self-regulation and reduce subsequent ability to effectively manage negative affect, consistent with ego depletion models of stigma and social exclusion (Baumeister et al., 2005; Inzlicht et al., 2006).

Our results also indicate that the increases in emotion dysregulation associated with peer victimization account for subsequent increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety, consistent with prior research documenting an association between emotion dysregulation and youth psychopathology (Garber et al., 1995; Suveg & Zeman, 2004). These findings make several novel contributions to the peer victimization literature. First, prior research has not clearly identified mechanisms linking victimization and internalizing symptoms. To date, the social-cognitive processes that have been found to account for the relationship between victimization and externalizing symptoms have not been found to link peer victimization and internalizing symptoms. Our findings provide novel evidence for emotion dysregulation as a mechanism in this association. Second, the few studies that have examined mechanisms accounting for the victimization-psychopathology association have utilized cross-sectional designs that cannot establish causal mechanisms (Hawker & Boulton, 2000). In contrast, this investigation tested a longitudinal mediation model with multiple assessments.

Analyses of reciprocal relations between symptomatology and subsequent victimization indicated that internalizing symptoms marginally predicted increases in relational, but not overt or reputational, victimization. On one hand, these findings are consistent with prior research linking internalizing symptoms to subsequent peer rejection (Hodges & Perry, 1999; Storch et al., 2005; Vernberg, 1990) and suggest that adolescents with symptoms of depression and anxiety may be more likely to be targets of relational but not other types of victimization by peers. These victimization experiences, in turn, place them at higher risk for the development of internalizing symptoms, perpetuating a cycle of victimization and distress. On the other hand, the longitudinal relationship between internalizing symptoms and subsequent victimization did not reach statistical significance in this study, suggesting a weak prospective relationship in our sample. Notably, a longitudinal association between adolescent internalizing symptoms and subsequent peer rejection has not been consistently identified in the literature (Vernberg et al., 1992). Prior research reporting a positive association has utilized predominantly White middle-class samples and slightly longer follow-up periods (Hodges & Perry, 1999; Storch et al., 2005), and the weaker association in our study may be related to differences in sample composition and/or follow-up.

We did not find evidence for a role of emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking internalizing symptoms to subsequent relational victimization. Internalizing symptoms were associated cross-sectionally with emotion dysregulation, but did not predict increases in emotion dysregulation over time. As such, emotion dysregulation could not serve as a mediator of the longitudinal association between internalizing symptoms and subsequent victimization. These findings point to the importance of identifying other mechanisms responsible for this association. One possible mechanism is social competence. Deficits in interpersonal skills and social competence are common among youth with internalizing symptoms (Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1994; Spence, Donovan, & Brechman-Touissant, 1999). Moreover, youth with internalizing symptoms and few friends are more likely to be victimized by peers than children who have more friendship relationships (Hodges, Malone, & Perry, 1997). As such, social competence represents a potential mechanism linking internalizing symptoms to subsequent peer victimization, pointing to an important avenue for future inquiry.

Our findings suggest that the mechanisms linking victimization to the development of internalizing symptoms differ depending on whether victimization experiences are overt or relational in nature. We provide evidence for the role of emotion dysregulation as a mechanism underlying the association between relational and reputational victimization and subsequent internalizing symptoms, but mediators of the relationship between overt victimization and such symptoms remain unclear. Emotion regulation processes not measured in the current study may serve to explain this relationship. In particular, overt victimization experiences may be more likely to elicit fear than relational victimization. For example, individuals from stigmatized groups who confront discrimination and victimization experience hypervigilance and fear of future threat (Blascovich, Mendes, Hunter, & Lickel, 2000; Mays, Cochran, & Barnes, 2007). We did not include measures that specifically tapped fear reactivity or dysregulated fear expression in this study. As such, fear dysregulation may in fact play a role in the association between overt victimization and internalizing symptoms, a possibility that should be examined in future research.

Adolescents who are victimized by peers represent important targets for interventions aimed at preventing the negative mental health sequelae of victimization experiences. Our results have important implications for preventive interventions that seek to reduce the prevalence of psychopathology among youth confronting peer-related stressors. Most interventions targeting victimized youth have been designed as school-based prevention programs aimed at reducing the prevalence of relational and physical aggression and changing beliefs about the acceptability of aggressive behavior (Olweus, 1994; Van Schoiack-Edstrom, Frey, & Beland, 2002). Although school-based programs are important, even effective programs fail to eliminate peer aggression completely. Consequently, the development of effective preventive interventions for youth experiencing psychological distress related to peer victimization represents a critical goal for the field. Indeed, a recent group-based intervention demonstrated efficacy in improving peer acceptance, social self-efficacy, and self-esteem and in reducing social anxiety and depression among victimized and bullied third graders over a one-year period (DeRosier, 2004; DeRosier & Marcus, 2005). The intervention utilized cognitive-behavioral and social learning techniques to improve social skills, bolster prosocial attitudes and behaviors, and enhance coping skills for managing bullying and peer pressure. Empirical evaluation of the efficacy of such an intervention among adolescents represents an important avenue for future research.

The current findings suggest that techniques targeting emotion regulation skills should be an additional component of clinical interventions with victimized adolescents. We are unaware of preventive interventions targeting this population that include such techniques, pointing to the importance of drawing on emotion regulation techniques used in other psychosocial treatments to improve upon existing interventions. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) includes a combination of cognitive-behavioral techniques and mindfulness and acceptance-based strategies, with a particular focus on building emotion regulation skills (Linehan, 1993). DBT has recently been demonstrated to reduce self-harm behaviors and depressive symptoms among adolescents engaging in repeated self-harm (James, Taylor, Winmill, & Alfoadari, 2007). Adolescent participants reported the emotion regulation skills training to be a particularly helpful component of the intervention. Another relevant intervention has been developed for youth depression that targets self-regulation of distress (Kovacs et al., 2006). Regulatory difficulties during periods of stress represent the primary intervention target. The therapy focuses on identifying children’s typical responses to distressing situations, identifying the contexts that elicit maladaptive management of distress, and replacing habitual maladaptive responses to distress with alternative responses from the child’s own repertoire of emotion regulation skills that ameliorate negative mood (Kovacs et al., 2006). Finally, a recent treatment specifically aimed at reducing engagement in rumination led to significant reductions in depression and associated comorbidity among adults (Watkins et al., 2007). None of these interventions specifically targets adolescents experiencing peer victimization; however, they utilize a set of intervention techniques that could be incorporated into existing intervention protocols targeting victimized adolescents. It is likely that inclusion of techniques targeting emotion regulation specifically, in addition to social skills and self-efficacy, will have the greatest efficacy in reducing psychiatric morbidity among adolescents exposed to peer victimization.

This study had a number of important methodological strengths that expand upon the literature examining mechanisms linking peer victimization and adolescent psychopathology. In particular, the use of a longitudinal design allowed us to conduct a stringent test of mediation, and a large sample with substantial racial/ethnic diversity participated. However, limitations of the current study must be acknowledged. Significant attrition was present across the three assessment points, although participants who did not complete follow-up assessments did not differ from participants who remained in the study on any variable of primary interest. A second limitation is our use of self-reported symptomatology rather than DSM-IV diagnoses. Although administration of a structured interview to establish diagnoses would represent a methodological improvement, the validity of the self-report measures used in this study is well-established (Timbremont, Braet, & Dreessen, 2004; Wood, Piacentini, Bergman, McCracken, & Barrios, 2002).

Our use of self-report measures of emotion regulation also represents a limitation of the study because of the difficulties inherent in disentangling initial emotion activation from emotion regulation (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004), leading to increased use of psychophysiological measures to assess emotion and emotion regulation (Gross, 1998; Silk et al., 2007). Such measures are useful in experimental settings, but they are unfeasible for use with large community samples. The emotion regulation questionnaires used in the current study attempted to separate emotion activation from regulation by assessing the extent to which participants engaged in different regulation strategies once a specific emotion had already been activated. Other widely used measures of emotion regulation utilize a similar approach (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991).

A final limitation involves the use of a self-report assessment of peer victimization. Cognitive biases present in youth with depression and anxiety may have impacted the frequency of peer victimization reported by participants with higher levels of symptoms (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004). We examined whether such biases were present by creating a dichotomous variable indicating whether peer victimization was present or absent at each assessment point. When the analyses were repeated using the dichotomous variables, our findings were unchanged, indicating that such biases did not likely impact the results. Nonetheless, shared-method variance remains a limitation given that symptoms of depression and anxiety were also assessed using self-report. Future studies should aim to include teacher-report and/or peer-nomination methods for assessing peer victimization. Despite these limitations, self-report assessment can capture victimization experiences of which peers and teachers are unaware and remains the traditional method for assessing peer victimization in the literature (LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; Prinstein et al., 2001; Vernberg, 1990), given that the relationship between victimization and distress is not impacted by the use of peer- versus self-report measures of victimization (Crick & Bigbee, 1998).

In sum, the current study identified emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking relational victimization to changes in internalizing symptoms among adolescents. Relational and reputational victimization led to increases in emotion dysregulation over time, and the emotion dysregulation generated by these victimization experiences accounted for the relationship between relational and reputational victimization experiences and internalizing symptoms. We found some evidence for a reciprocal relationship between internalizing symptoms and subsequent relational victimization, but this association was not accounted for by emotion dysregulation. These results suggest important avenues for intervention research targeting rejected and victimized youth.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, Ph.D. and Noah Shamosh, Ph.D. for their invaluable guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/ccp.

References

- Abela JR, Brozina K, Haigh EP. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and seventh-grade children: a short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:515–527. doi: 10.1023/a:1019873015594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 6.0 User's Guide. Chicago: SPSS, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Twenge JM. Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:589–604. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich J, Mendes WB, Hunter S, Lickel B. Stigma, threat, and social interactions. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The social psychology of stigma. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW. Life events and affective disorder: Replications and limitations. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1993;55:248–259. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO. Life events and depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth TL. Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Lochman JE, Terry R, Hyman C. Predicting early adolescent disorder from childhood aggression and peer rejection. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:783–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. Parent-child relationships in the transition to adolescence: Continuity and change in interaction, affect, and cognition. In: Monetmayor R, Adams G, Gullotta T, editors. Advances in adolescent development: Vol 2. From childhood to adolescence: A transitional period? Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Prinstein MJ. Applying depression-distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:325–335. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier ME. Building relationships and combating bullying: Effectiveness of a school-based social skills group intervention. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:196–201. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier ME, Marcus SR. Building friendships and combating bullying: Effectiveness of S.S.GRIN at one-year follow-up. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:140–150. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Fontaine R, et al. Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior in children. Child Development. 2003;74:374–393. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Adversity, stress, and psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC, Maszk P, Smith M, Karbon M. The role of emotionality and regulation in children's social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1995;66:1360–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Braafladt N, Weiss B. Affect regulation in depressed and nondepressed children and young adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Malhi GS. Do bullied children become anxious and depressed adults? A cross-sectional investigation of the correlates of bullying and anxious depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:201–208. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000202491.99719.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for expression, experience, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;24:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(1):128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Malone MJ, Perry DG. Individual risk and social risk as interacting determinants of victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1032–1039. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, McKay L, Aronson J. Stigma as ego depletion: How being the target of prejudice affects self-control. Psychological Science. 2006;17:262–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AC, Taylor A, Winmill L, Alfoadari K. A preliminary community study of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) with adolescent females demonstrating persistent, deliberate self-harm (DSH) Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2007;13:148–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Psychoneuroimmunology: Psychological influences on immune function and health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:537–547. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishton JM, Wadaman KF. Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1994;54:757–765. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Sherrill J, George CJ, Pollack M, Tumuluru RV, Ho V. Contextual emotion-regulation therapy for childhood depression: Description and pilot testing of a new intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:892–903. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000222878.74162.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGreca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Ham M. Stress and “storm and stress” in early adolescence: The relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Lampman-Petraitis C. Daily emotional stress as reported by children and adolescents. Child Development. 1989;60:1250–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Moneta G, Richards MH, Wilson S. Continuity, stability, and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Development. 2002;73:1151–1165. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Richards MH. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: Changing developmental contexts. Child Development. 1991;62:284–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR. Epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(10):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Examining the question, weighing the evidence. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Losoya S, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Developmental issues in the study of coping. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1998;22:287–313. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:176–190. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahady Wilton MM, Craig WM, Pepler DJ. Emotional regulation and display in classroom victims of bullying: Characteristic expressions of affect, coping styles and relevant contextual factors. Social Development. 2000;9:226–245. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JDA, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Mechanisms linking stressful life events and mental health problems in a prospective, community-based sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T, King N, Bogie N. Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:753–772. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:20–28. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: Long-term outcomes for the victims and an effective school-based intervention program. In: Huesmann LR, editor. Aggressive behavior: Current perspectives. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Penza-Clyve S, Zeman J. Initial validation of the emotion expression scale for children (EESC) Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:540–547. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Aikins JW. Cognitive mediators of the longitudinal association between peer rejection and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:147–158. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019767.55592.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Cheah CSL, Guyer AE. Peer victimization, cue interpretation, and internalizing symptoms: Preliminary concurrent and longitudinal findings for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:11–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:330–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Assessment of depression in children and adolescents by self-report measures. In: Reynolds WM, Johnston HF, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. Interpersonal functioning and depressive symptoms in childhood: Addressing the issues of specificity and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:355–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02168079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Dodge KA, Coie JD. The emergence of chronic peer victimization in boys' play groups. Child Development. 1993;64:1755–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb04211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:601–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behaviors. Child Development. 2003;74:1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Vanderbilt-Adriance E, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Whalen DJ, Ryan ND, et al. Resilience among children and adolescents at risk for depression: Mediation and moderation across social and neurobiological context. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:841–865. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim L, Zeman J. Emotion regulation factors as mediators between body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms in early adolescent girls. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:478–496. [Google Scholar]

- Sim L, Zeman J. The contribution of emotion regulation to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in early adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation model. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological Methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Kendall PC. A preliminary study of the emotional understanding of youth referred for treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:319–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH, Donovan C, Brechman-Touissant M. Social skills, social outcomes, and cognitive features of childhood social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;102:211–221. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch E, Masia-Warner C, Crisp H, Klein RG. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescence: A prospective study. Aggressive Behavior. 2005;31:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Suveg C, Zeman J. Emotion regulation in children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:750–759. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timbremont B, Braet C, Dreessen L. Assessing depression in youth: Relation between the Children’s Depression Inventory and a structured interview. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:149–157. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort differences on the children's depression inventory: a meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):578–588. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoiack-Edstrom L, Frey KS, Beland K. Changing adolescents'attitudes about relational and physical aggression: An early evaluation of a school-based intervention. School Psychology Review. 2002;31:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM. Psychological adjustment and experiences with peers during early adolescence: Reciprocal, incidental, or unidirectional relationships? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:187–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00910730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, Abwender DA, Ewell KK, Beery SH. Social anxiety and peer relationships in early adolescence: A prospective analysis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21:189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, Fonagy P, Twemlow S. Preliminary Report of the Topeka Peaceful Schools Project. Topeka, KS: Menninger Clinic; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, Jacobs AK, Hershberger SL. Peer victimization and attitudes about violence during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:386–395. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER, Scott J, Wingrove J, Rimes K, Bathurst N, Steiner H, et al. Rumination-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for residual depression: A case series. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2144–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;31:335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K, Penza-Clyve S. Development and initial validation of the Children’s Sadness Management Scale. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2001;25:187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K, Suveg C. Anger and sadness regulation: Predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:393–398. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]