Abstract

AIM: To study the growth inhibitory and apoptotic effects of Scutellaria barbata D.Don (S. barbata) and to determine the underlying mechanism of its antitumor activity in mouse liver cancer cell line H22.

METHODS: Proliferation of H22 cells was examined by MTT assay. Cellular morphology of PC-2 cells was observed under fluorescence microscope and transmission electron microscope (EM). Mitochondrial transmembrane potential was determined under laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM) with rhodamine 123 staining. Flow cytometry was performed to analyze the cell cycle of H22 cells with propidium iodide staining. Protein level of cytochrome C and caspase-3 was measured by semi-quantitive RT-PCR and Western blot analysis. Activity of caspase-3 enzyme was measured by spectrofluorometry.

RESULTS: MTT assay showed that extracts from S. barbata (ESB) could inhibit the proliferation of H22 cells in a time-dependent manner. Among the various phases of cell cycle, the percentage of cells in S phase was significantly decreased, while the percentage of cells in G1 phase was increased. Flow cytometry assay also showed that ESB had a positive effect on apoptosis. Typical apoptotic morphologies such as condensation and fragmentation of nuclei and blebbing membrane of apoptotic cells could be observed under transmission electron microscope and fluorescence microscope. To further investige the molecular mechanism behind ESB-induced apoptosis, ESB-treated cells rapidly lost their mitochondrial transmembrane potential, released mitochondrial cytochrome C into cytosol, and induced caspase-3 activity in a dose-dependent manner.

CONCLUSION: ESB can effectively inhibit the proliferation and induce apoptosis of H22 cells involving loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, release of cytochrome C, and activation of caspase-3.

Keywords: Scutellaria barbate, Hepatoma, Apoptosis, Mitochondrial transmembrane potential, Serum pharmacology

INTRODUCTION

Scutellaria barbata D.Don (S. barbata) is a perennial herb, also known as Ban-Zhi-Lian (barbat sskullcap) in traditional Chinese medicine. It is mainly distributed in southern China and has been used as an antitumor agent for lung cancer, digestive system cancer, hepatoma, breast cancer, and chorioepithelioma as well as an anti-inflammatory agent and a diuretic in China and Korea[1-9]. Extracts from S. barbata (ESB) have in vitro growth inhibitory effects on a number of human cancers including leukemia, colon cancer, hepatoma and skin cancer[4-10]. However, its antitumor mechanism still remains unclear.

It was reported that many Chinese herbs have anticancer properties and induce apoptosis[11]. Three apoptotic pathways have been addressed, including the mitochondrial pathway[12,13], death receptor pathway[14], and endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis pathway[15]. The mitochondrial pathway initiates apoptosis in most physiological and pathological situations. Permeabilization outside mitochondrial membrane plays the most important role in mitochondrial apoptosis. In the mitochondria-initiated pathway, mitochondria undergoing permeability transition release apoptogenic proteins such as cytochrome C or apoptosis-inducing factor from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol[16]. Released cytochrome C can activate caspase-9, and activated caspase-9 in turn cleaves and activates executioner caspase-3. After caspase-3 activation, some specific substrates for caspase-3 such as poly (ADP-ribose) and polymerase (PARP) are cleaved, and eventually lead to apoptosis[17].

In this study, S. barbata extract showed anti-tumor activity in vitro and could inhibit the growth of mouse H22 hepatoma cells by inhibiting cell apoptosis and cytotoxic effects, demonstrating that the extract from S. barbata can strongly inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis of H22 cells through the mitochondrial dysfunction pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and animals

New bovine serum (Gibco, USA), RPMI-1640 medium(Gibco, USA), propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma, USA), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ribonuclease (RNase A), rhodanmin123 (Rh123), and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenytetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against caspase-3 and cytochrome C were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, USA). Apoptotic cell Hoechst 33258 detection kit was purchased from Nanjing Kai-ji Biotechnology Development Ltd (China), and fluorescence probes Rhodamine 123 was purchased from Sigma (USA). Male SD rats weighing 220-250 g were purchased from the Experiment Animal Center, Medical School of Xi’an Jiaotong University (China).

Preparation of S. barbata extract and drug containing serum

S. barbata crude extract (ESB) was purchased from Xi’an Zhongxin Biotechnology Development Ltd (China). One kilogram of S. barbata was extracted three times with water as previously described[18]. Final qualification was 10:1. More specifically, stems of SB were cut into small pieces, boiled in water for 2 h, put into a filtrate, and concentrated by spray drying until the specific density reached 1.15-1.18.

“Serum pharmacology” was used to study the in vitro pharmacological activity of herb medicine as previously described[19]. ESB-containing serum was prepared as previously described[18,20]. Twenty male SD rats were randomly divided into control group, high ESB dose group, medium ESB dose group, and low ESB dose group (n = 5). Rats in the high, medium and low ESB dose groups received intragastric ESB of 6, 3 and 1.5 g/d per kg of body weight. Rats in the control group received normal saline, twice a day for 3 d. Two hours after the last administration, blood was immediately obtained from the heart and kept at room temperature for 4 h. The serum was separated by centrifugation at 2400 r/min for 10 min, collected following twice of filtration with a 0.22 μm cellulose acetate membrane, calefied in 56°C water for 30 min, and stored at -20°C for use.

Cell lines and culture

Mouse H22 hepatoma cells, purchased from Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China), were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA), 1 × 105 U/L penicillin and 100 mg/L streptomycin in an incubator containing a humidified atmosphere with 50 mL CO2 at 37°C. The cells were subcultured until reaching logarithmic growth phase. The viability of H22 cells, stained with trypan blue, was above 97%.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) dye reduction assay (Sigma, USA). H22 cells were seeded at a concentration of 5 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well plate, and grown at 37°C until adherence. At end of the treatment, 50 μg/10 μL of MTT was added and the cells were incubated for another 4 h. Two hundred μL of DMSO was added to each well after the supernatant was removed. After the plate was shaken for 10 min, cell viability was detected by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm wavelength using an enzyme-labeling instrument (EX-800 type) in quintuplicate.

Cell viability (%) = the absorbance of experimental group/the absorbance of blank control group × 100%.

Detection of morphological apoptosis

Staining of cells with uranyl acetate and lead citrate was performed to detect morphological changes. Briefly, adherent H22 cells were treated with ESB at a high dose for 48 h. The treated cells were digested with pancreatin and fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde precooled at 4°C for 2 h. To make ultra-thin sections of copper, cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 1% osmic acid for an additional hour, dehydrated in acetone and embedded in epoxide resin. After stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, the sections were examined under a Hitachi-800 transmission electron microscope as previously described[21].

Nuclear staining

H22 cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with PBS and fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde for 1 h at room temperature. The fixed cells were washed with PBS, stained with 200 μmol/L Hoechst 33258 for 10 min. Changes in nuclei after stained with Hoechst 33258 were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, BX-60, Japan).

Cell cycle analysis

H22 cells were incubated at 5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates, treated with a homologous drug for 48 h. The detached and attached cells were harvested and fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol at -20°C overnight. After fixation, cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in 1 mL PBS containing 1 mg/mL RNase (Sigma) and 50 μg/mL PI (Sigma), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Samples of 10 000 cells were then analyzed for DNA content by FACScan flow cytometry (Beckman, USA), and cell cycle phase distributions were analyzed with the CellQuest acquisition software(BD Biosciences).

Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondria transmembrane potential (∆ψm) was detected under laser scanning confocal microscope(LSCM) with Rhodamine 123 (Rh123) staining as previously described[22]. About 1 × 106 cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with PBS, and incubated with Rh123 at the final concentration of 1 μL/mL for 20 min at 37°C in the dark, centrifuged at 1000 r/min for 5 min, washed twice with a medium, resuspended in the medium, cultured at 37°C in an incubator containing 50 mL CO2 for 60 min. Fluorescence intensity was determined at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm, emission wavelength of 530 nm under a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, FluoView™ FV300, Japan). The fluorescence intensity of Rhodamine 123 in cells represents the mitochondrial membrane potential[23].

Western blot analysis

H22 cells (2.5 × 107) were collected by centrifugation at 2000 r/min for 10 min at 4°C, washed twice with cold PBS (pH 7.2), centrifuged at 2000 r/min for 10 min. Protein content was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay reagent with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Total proteins (30 μg/lane) were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a 0.45 μm PVDF membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The blots were incubated with the desired primary antibody overnight at the following dilutions: caspase 3 (1:1000), cytochrome C (1:1500), and β-actin (1:1500). Primary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The immunoblots were analyzed by densitometry on a GelDoc 2000 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. USA) as previously described[17,24].

Assay for caspase-3 activity

Caspase-3 activity was assayed using the caspase-3 activity assay kit (Nanjing Kai-ji, China) as previously described[25,26]. In brief, standard curve was plotted by detecting the absorbance of standard samples with terminal concentrations at each well, respectively. After 1 h incubation at room temperature, H22 cells were collected and lysed completely in a caspase assay buffer. The activity of caspase-3 was assayed in triplicate using a plate-reading luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA) at the wavelength of 405 nm. Nkat was used to represent the activity measured[25].

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the statistical software SPSS 11.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of ESB on proliferation of H22 cells

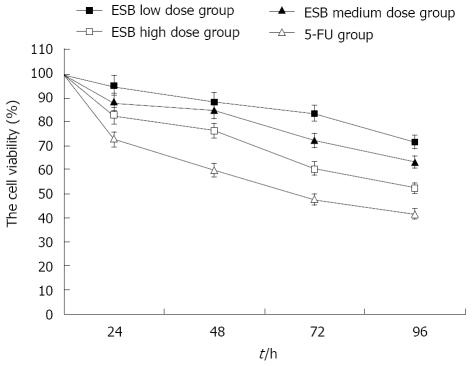

H22 cells were treated with different doses of ESB.The growth rate of H22 cells was evaluated after 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, respectively. The cell viability of H22 cells in different ESB treatment groups was significantly higher than that in 5-FU treatment group (Figure 1). High and medium dose ESB inhibited the proliferation of H22 cells (P < 0.05), while low dose ESB could not obviously inhibit the proliferation of H22 cells (P > 0.05). MTT assay showed that high and medium dose ESB inhibited the proliferation of H22 cells in vitro in a time-dependent manner.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of H22 cell proliferation by ESB. H22 cells were treated with different doses of ESB. The number of cells was determined at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, respectively. The viability of cells was detected by MTT assay. ANOVA analysis showed that the growth of H22 cells was inhibited by ESB in a dose- and time- dependent manner (P < 0.05).

Morphological observation of apoptosis of H22 cells induced by ESB

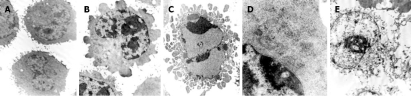

High resolution transmission electron microscopy showed that normal H22 cells were round and regular in shape with chromatin margination in few tumor cells (Figure 2A). After treatment with a high ESB dose for 48 h, a part of nuclear membrane domed outward with a sharp angle. The typical morphologies of apoptotic H22 cells such as chromatic agglutination and fragmentation of nuclei, chondriosome swelling, formation of apoptotic body, could be observed in high ESB dose group (Figure 2B-D), while in 5-FU group, cellular swelling and necrosis could be observed in many fields of vision.

Figure 2.

Morphological observation of H22 cells by EM after treatment. A: normal hepatoma H22 cells (5000 ×); B: karyopyknosis and chromatic agglutination in high ESB dose group (5000 ×); C: apoptotic body in high ESB dose group (5000 ×); D: chondriosome swelling in high ESB dose group (6000 ×); E: cellular swelling and necrosis in 5-FU group (5000 ×).

Detection of apoptosis of H22 cells by Hoechst 33258 staining

After treatment with different doses of ESB for 48 h, H22 cells were stained with Hoechst 33258 and observed under a fluorescence microscope. The condensely stained chromatin of apoptotic cells was more bright than that of normal cells. The characteristics of apoptosis, such as nuclear shrinkage, DNA condensation and fragmentation, were found in ESB treatment group (Figure 3B-D), while no apoptosis occurred in blank control group (Figure 3A). The percentage of apoptotic cells in control group and low and high ESB dose groups was 3.36% ± 2.14%, 14.57% ± 4.28%, 43.15% ± 5.33%, 72.65% ± 6.52%, respectively. Furthermore, the number of apoptotic cells gradually increased in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 3.

Cell apoptosis observed with Hoechst 33258 staining under a fluorescence microscope (× 200). After cells were treated with different doses of ESB for 48 h, Hoechst 33258 staining was used to observe apoptotic cells as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The number of apoptotic cells gradually increased in a dose-dependent manner with marked morphological changes found in cell apoptosis including condensation of chromatin and nuclear fragmentation. A: Control group; B: Low dose treated group; C: Medium dose treated group; D: High dose treated group.

Effect of ESB on cell cycle distribution by flow cytometry

The effects of ESB on cell cycles were analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells was significantly decreased at S phase and increased at G1 phase in high ESB dose group.

The sub-G1 population indicated apoptotic-associated chromatin degradation. The ratio of cell apoptosis in blank control group, and low, medium, high ESB dose groups was 0.51%, 1.07%, 3.15%, 7.83%, respectively. There was significantly difference between the 4 groups (P < 0.05). These results suggest that high ESB dose can induce cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase and apoptosis in H22 cells ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of ESB on cell cycle and apoptosis of H22 cells by flow cytometry (mean ± SD)

| Groups | n | G0/G1 | S | G2/ M | Apoptosis rate |

| Control | 5 | 37.63 ± 2.12 | 32.73 ± 2.24 | 21.75 ± 1.52 | 0.51 ± 0.12 |

| ESB low dose | 5 | 39.35 ± 2.25 | 33.56 ± 3.12 | 21.20 ± 1.27 | 1.07 ± 0.15 |

| ESB medium dose | 5 | 45.91 ± 2.56a | 30.65 ± 2.64 | 17.15 ± 1.34a | 3.15 ± 0.27a |

| ESB high dose | 5 | 56.05 ± 2.37b | 21.33 ± 3.42b | 12.30 ± 1.25b | 7.83 ± 0.43b |

Cell cycle distributions in control and ESB-treated cells were determined by PI staining and flow cytometric analysis. Results presented were representative of three independent experiments.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 vs control group.

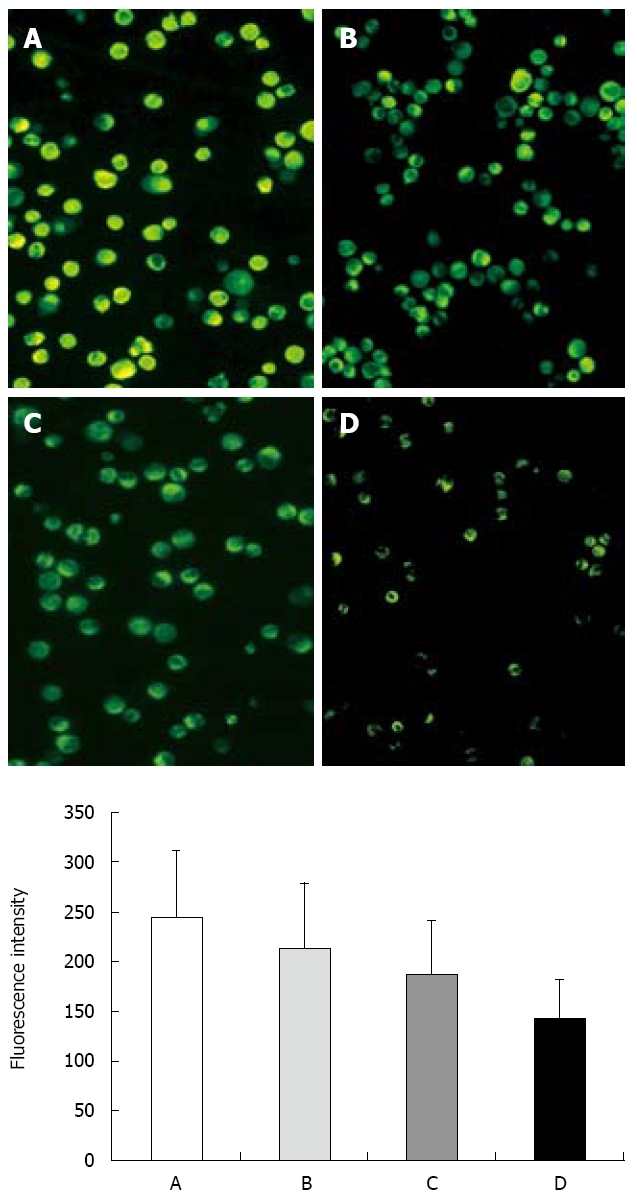

Effect of ESB on mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondria play an essential role in apoptosis. To assess whether ESB affects the function of mitochondria, mitochondrial membrane potential was detected under a laser scanning confocal microscope with Rh123 staining. The fluorescence intensity of Rhodamine123 in H22 cells of blank control group was the strongest (Figure 4). After treatment with different doses of ESB for 48 h, ANOVA analysis showed that the fluorescence intensity was decreased in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of ESB on ∆ψm measured with laser scanning confocal microscope by staining with Rhodamine 123 (200 ×). A: Control group; B: Low ESB dose group; C: Medium ESB dose group; D: High ESB dose group. Fluorescence intensity (FI) indicates membrane potential of mitochondria in the cells. FI was decreased in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.05, ANOVA analysis).

Caspase-3 activity in ESB-induced apoptosis of H22 cells

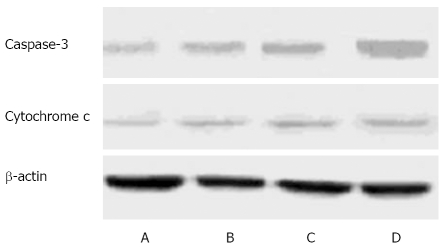

Caspase-3, acting on downstream of the mitochondrial signaling pathway, is a major mediator of apoptosis. Dysfunction of mitochondria provoked us to detect the changes of caspase-3 activity in H22 cells following ESB treatment. The expression intensities of caspase-3 protein in the control and low-high ESB dose groups were 0.21 ± 0.02, 0.33 ± 0.04, 0.59 ± 0.03, and 0.85 ± 0.05, respectively (Figure 5). Western blot analysis revealed that there was a gradual increase in caspase-3 protein in low-high ESB dose groups (P < 0.05), indicating that caspase-3 can be activated by ESB.

Figure 5.

Protein level of caspase-3 and cytochrome C in H22 cells. A: Control group; B: Low ESB dose group; C: Medium ESB dose group; D: High ESB dose group. After treatment with different doses of ESB for 48 h, cellular proteins were detected by Western blot analysis.

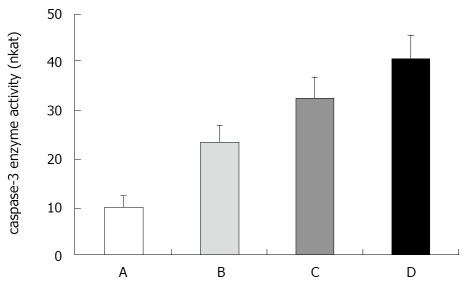

Caspase-3 activities were detected after treatment with different doses of ESB for 48 h, showing that caspase-3 activity was induced by ESB in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of ESB on caspase-3 enzyme activity in H22 cells. A: Control group; B: Low ESB dose group; C: Medium ESB dose group; D: High ESB dose group. There was a dose dependent increase in activity of caspase-3 enzyme in ESB treated cells (P < 0.05). This assay was done triplicate, independently. Nkat was used to represent activity measured.

Release of cytochrome C from mitochondria in ESB-induced apoptosis

Cytochrome C release from mitochondria into cytosol is a critical step in the apoptotic cascade. The reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential may facilitate the release of cytochrome C, which will then activate the apoptotic pathway to trigger cell death. The protein level of cytochrome C in cytosol was measured in H22 cells treated with different doses of ESB by Western blot analysis with mouse monoclonal cytochrome C antibodies. As shown in Figure 5, the amount of cytosolic cytochrome C in the cytosolic fraction after ESB treatment was significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

S. barbata, which has been traditionally used in treatment of inflammation, hepatitis, tumor and gynecological diseases in China and Korea[1-9]. Studies have shown that S. barbata contains a large number of alkaloids and flavones, alkaloid, sterides, and polysaccharides[27,28]. However, the active site of chemical structure for antitumor activity has not been fully determined[29]. Recent studies indicate that S. barbata extract (ESB) is effective against hepatoma, lung and digestive system cancers, et al[4-10], and can be used in combination with other traditional Chinese medicines in treatment of other tumors.

In pharmacology study, crude Chinese drugs or their compounds are often added directly into the culture system of cells or organs in vitro[30]. However,, experimental results in vitro are often different from those in vivo. Serum pharmacology has been extensively used to study the effects and mechanisms of Chinese drugs in vitro[30]. It is believed that serum pharmacology is more scientific and beter for Chinese drugs than traditional pharmacology in which crude drugs are directly added into the culture system of cells or organs in vitro[19-20,30,31]. In this study, we investigated the effects of ESB on inducing apoptosis of H22 cells with serum pharmacology.

H22 cells were treated with different doses of ESB containing serum, and the growth rate of H22 cells was evaluated by MTT assay after 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, respectively. High and medium ESB dose inhibited the proliferation of H22 cells, while low ESB dose could not obviously inhibit the proliferation of H22 cells. MTT assay showed high and medium ESB dose inhibited the proliferation of H22 cells in vitro in a time-dependent manner, which may provide useful information for development of anti-tumor drugs.

Morphological changes of apoptosis include membrane blebbing, cell shrinkage, chromatin conden-sation, DNA fragmentation and formation of apoptotic bodies[32]. These morphological changes were also observed in our study under transmission electron microscopy and fluorescence microscope after treatment with a high ESB dose for 48 h. Typical morphologies of apoptotic H22 cells, such as chromatic agglutination and fragmentation of nuclei, chondriosome swelling, formation of apoptotic body, were observed in ESB high ESB dose group (Figure 2B-D), but no apoptosis occurred in blank control group. Furthermore, fluorescence microscopy showed that the number of apoptotic cells gradually increased in a dose-dependent manner.

Blocking of cell cycle is one of the mechanisms of ESB by which the growth and proliferation of tumor cells are inhibited[33]. Flow cytometry showed that cell apoptosis was significantly decreased at S-phase, increased at G1-phase, and reached its peak at subG1- phase. The blocking of cell cycle may be one of the mechanisms of ESB by which the growth of H22 cells is inhibited and cell apoptosis is induced.

Mitochondria play a critical role in apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents[12-14]. Many agents can induce, directly or indirectly, apoptosis by insult to the mitochondria[34,35]. Apoptosis could cause loss of Δψm and release of cytochrome C into cytosol, and induce caspase-9-dependent activation of caspase-3[13]. In this study, the effect of ESB on Δψm was examined using Rhodamine 123, a mitochondrial potential probe, showing that H22 cells lost Δψm following ESB treatment. Forty-eight hours after ESB treatment, the cells exhibited significant alterations in Δψm, and the fluorescence intensity of disruption of Δψm gradually decreased in a dose-dependent manner

One of the major apoptotic pathways is activated by the release of cytochrome C from mitochondria into cytosol[36], which is the hallmark of cells undergoing apoptosis. In this study, Western blotting analysis was performed to measure the protein level of cytochrome C in H22 cells after treatment with different doses of ESB. The amount of cytosolic cytochrome C in the cytosolic fraction after ESB treatment was increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6).

Caspases are cystein proteases that play a key role in the execution phase of apoptosis[37]. Caspase-3, a member of the family of caspases, extensively studied as “the executor of apoptosis”, plays a crucial role in cell death[38]. Apoptosis mediated by caspase-3 occurs in many cancer cells. In this study, Western blot analysis revealed that caspase-3 protein was gradually increased in the low-high ESB dose groups. At the same time, caspase-3 enzyme activity was increased in a dose-dependent manner. These results indicate that caspase-3 can be activated by ESB. ESB treatment resulted in loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, release of cytochrome C and caspase-3, demonstrating that ESB induces apoptosis and mitochondria are involved in apoptosis mediated by ESB.

In conclusion, ESB has antiproliferative activities against H22 cells by inducing apoptosis involving loss of ∆ψm, release of cytochrome C, and activation of caspase-3.

COMMENTS

Background

Medicinal plants have been used as traditional remedies for hundreds of years. Among them, Scutellaria barbata D.Don (S. barbata) has been traditionally used in treatment of hepatitis, inflammation, osteomyelitis and gynecological diseases in China. Studies indicate that extracts from S. barbata have growth inhibitory effects on a number of human cancers. Reports are available on the treatment of lung, breast and digestive system cancer, hepatoma, and chorioepithelioma with S. barbata extracts. However, the underlying mechanism of the antitumor activity of S. barbata extracts remains unclear.

Research frontiers

Studies have confirmed that many Chinese herbs have antitumor properties and induce apoptosis. In the process of signal transduction of cell apoptosis induced by drugs, mitochondria play a great role in promoting apoptosis signal and releasing caspase. Permeabilization of the outside mitochondrial membrane plays the most important role in mitochondrial apoptosis, during which loss of Δψm and release of cytochrome C into cytosol, and caspase-9- dependent activation of caspase-3 occur sequentially.

Innovations and breakthroughs

There is no evidence that the mitochondrial pathway is involved in apoptosis induced by S. barbata. The present study was undertaken by culturing mouse liver cancer H22 cells treated with serum containing different concentrations of ESB. ESB containing serum induced apoptosis of H22 cells, and apoptosis was involved in loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, release of cytochrome C, and activation of caspase-3.

Applications

This experimental study on the mechanism of the antitumor activity of S. barbata, may offer new evidence for S. barbata in the treatment of hepatoma in clinical practice.

Terminology

ESB is an extract from Scutellaria barbata; ∆ψm indicates mitochondrial transmembrane potential;1 nanokatal defined as the amount of enzyme required to increase the rate of reaction by 1 nmol/s under defined assay conditions.

Peer review

This study examined the anti-tumour effects of Scutellaria barbate. The authors used serum containing extract from S. Barbata (ESB) to determine its effect on proliferation of H22 hepatoma cells in vitro. ESB inhibited cell proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest at Go/G1 phase and by increasing apoptosis with a reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential, release of cytochrome C and capase-3 activation. This work is novel and improves our understanding of the mechanisms of action of ESB.

Footnotes

Supported by The Science and Technology Foundation of Shaanxi Province, China, No. 2006K16-G5(1) and Sci-tech Program of Xi’an City, China, No. YF07175

Peer reviewers: Debbie Trinder, PhD, School of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Western Australia, Fremantle Hospital, PO Box 480, Fremantle 6959, Western Australia, Australia; Dr. Katja Breitkopf, Department of Medicine II, University Hospital Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, Theodor-Kutzer-Ufer 1-3, 68167 Mannheim, Germany

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Lee TK, Lee DK, Kim DI, Lee YC, Chang YC, Kim CH. Inhibitory effects of Scutellaria barbata D. Don on human uterine leiomyomal smooth muscle cell proliferation through cell cycle analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin CC, Shieh DE. The anti-inflammatory activity of Scutellaria rivularis extracts and its active components, baicalin, baicalein and wogonin. Am J Chin Med. 1996;24:31–36. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X96000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee TK, Kim DI, Song YL, Lee YC, Kim HM, Kim CH. Differential inhibition of Scutellaria barbata D. Don (Lamiaceae) on HCG-promoted proliferation of cultured uterine leiomyomal and myometrial smooth muscle cells. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2004;26:329–342. doi: 10.1081/iph-200026841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goh D, Lee YH, Ong ES. Inhibitory effects of a chemically standardized extract from Scutellaria barbata in human colon cancer cell lines, LoVo. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:8197–8204. doi: 10.1021/jf051506+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin X, Zhou J, Jie C, Xing D, Zhang Y. Anticancer activity and mechanism of Scutellaria barbata extract on human lung cancer cell line A549. Life Sci. 2004;75:2233–2244. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cha YY, Lee EO, Lee HJ, Park YD, Ko SG, Kim DH, Kim HM, Kang IC, Kim SH. Methylene chloride fraction of Scutellaria barbata induces apoptosis in human U937 leukemia cells via the mitochondrial signaling pathway. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;348:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suh SJ, Yoon JW, Lee TK, Jin UH, Kim SL, Kim MS, Kwon DY, Lee YC, Kim CH. Chemoprevention of Scutellaria bardata on human cancer cells and tumorigenesis in skin cancer. Phytother Res. 2007;21:135–141. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai ZJ, Liu XX, Xue Q, Ji ZZ, Wang XJ, Kang HF, Guan HT, Ma XB, Ren HT. [Anti-proliferative and apoptosis-inducing activity of Scutellaria barbate containing serum on mouse’s hepatoma H22 cells] Zhongyaocai. 2008;31:550–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin JM, Liu Y, Luo RC. [Inhibition activity of Scutellariae barbata extracts against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells] Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2006;26:591–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee TK, Cho HL, Kim DI, Lee YC, Kim CH. Scutellaria barbata D. Don induces c-fos gene expression in human uterine leiomyomal cells by activating beta2-adrenergic receptors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:526–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.014315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu ZH, Wei PK, Xu L, Qin ZF, Shi J. Anticancer effect of jinlongshe granules on in situ-transplanted human MKN-45 gastric cancer in nude mice and xenografted sarcoma 180 in Kunming mice and its mechanism. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2890–2894. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i18.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohamad N, Gutierrez A, Nunez M, Cocca C, Martin G, Cricco G, Medina V, Rivera E, Bergoc R. Mitochondrial apoptotic pathways. Biocell. 2005;29:149–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delivani P, Martin SJ. Mitochondrial membrane remodeling in apoptosis: an inside story. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:2007–2010. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S. Molecular signaling in death receptor and mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis (Review) Int J Oncol. 2003;22:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakhshi J, Weinstein L, Poksay KS, Nishinaga B, Bredesen DE, Rao RV. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program in mouse melanoma cells: effect of curcumin. Apoptosis. 2008;13:904–914. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0221-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoye AT, Davoren JE, Wipf P, Fink MP, Kagan VE. Targeting mitochondria. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:87–97. doi: 10.1021/ar700135m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Wang LJ, Qiu GF, Yu JQ, Liang SC, Hu XM. Apoptosis of Hela cells induced by extract from Cremanthodium humile. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:2040–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang YH, Liu JT, Wen BY, Xiao XH. In vitro inhibition of proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells by serum of rats treated with Dahuang Zhechong pill. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miura D, Miura Y, Yagasaki K. Effect of apple polyphenol extract on hepatoma proliferation and invasion in culture and on tumor growth, metastasis, and abnormal lipoprotein profiles in hepatoma-bearing rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:2743–2750. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishida S, Satoh H. Mechanisms for the vasodilations induced by Ginkgo biloba extract and its main constituent, bilobalide, in rat aorta. Life Sci. 2003;72:2659–2667. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma G, Yang C, Qu Y, Wei H, Zhang T, Zhang N. The flavonoid component isorhamnetin in vitro inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in Eca-109 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;167:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao JX, Guo FL, Bai DC, Wang XX. [Effects of fuzheng yiliu granules on apoptotic rate and mitochondrial membrane potential of hepatocellular carcinoma cell line H22 from mice] Zhongxiyi Jiehe Xuebao. 2006;4:271–274. doi: 10.3736/jcim20060310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blattner JR, He L, Lemasters JJ. Screening assays for the mitochondrial permeability transition using a fluorescence multiwell plate reader. Anal Biochem. 2001;295:220–226. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CJ, Hsu MH, Huang LJ, Yamori T, Chung JG, Lee FY, Teng CM, Kuo SC. Anticancer mechanisms of YC-1 in human lung cancer cell line, NCI-H226. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feeney B, Pop C, Swartz P, Mattos C, Clark AC. Role of loop bundle hydrogen bonds in the maturation and activity of (Pro)caspase-3. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13249–13263. doi: 10.1021/bi0611964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng B, Chang Q, Wang L, Hu Q, Wang Y, Tang J, Liu X. Suppression of human ovarian SKOV-3 cancer cell growth by Duchesnea phenolic fraction is associated with cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang WS, Zhou YW, Ye YH, Du N. [Studies on the flavonoids in herb from Scutellaria barbata] Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2004;29:957–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai SJ, Sun JY, Ren Y, Liu K, Shen L. Bioactive ent-clerodane diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata. Planta Med. 2007;73:1217–1220. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-990215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu J, Lei J, Yu H, Cai X, Zou G. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Scutellaria barbata. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:881–884. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bochu W, Liancai Z, Qi C. Primary study on the application of Serum Pharmacology in Chinese traditional medicine. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2005;43:194–197. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Er HM, Cheng EH, Radhakrishnan AK. Anti-proliferative and mutagenic activities of aqueous and methanol extracts of leaves from Pereskia bleo (Kunth) DC (Cactaceae) J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113:448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rello S, Stockert JC, Moreno V, Gamez A, Pacheco M, Juarranz A, Canete M, Villanueva A. Morphological criteria to distinguish cell death induced by apoptotic and necrotic treatments. Apoptosis. 2005;10:201–208. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-6075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigounas G, Hooker J, Anagnostou A, Steiner M. S-allylmercaptocysteine inhibits cell proliferation and reduces the viability of erythroleukemia, breast, and prostate cancer cell lines. Nutr Cancer. 1997;27:186–191. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fulda S, Susin SA, Kroemer G, Debatin KM. Molecular ordering of apoptosis induced by anticancer drugs in neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4453–4460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim KC, Kim JS, Son JK, Kim IG. Enhanced induction of mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in human leukemia HL-60 cells by the Ganoderma lucidum and Duchesnea chrysantha extracts. Cancer Lett. 2007;246:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lalier L, Cartron PF, Juin P, Nedelkina S, Manon S, Bechinger B, Vallette FM. Bax activation and mitochondrial insertion during apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:887–896. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen YC, Shen SC, Lee WR, Hsu FL, Lin HY, Ko CH, Tseng SW. Emodin induces apoptosis in human promyeloleukemic HL-60 cells accompanied by activation of caspase 3 cascade but independent of reactive oxygen species production. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:1713–1724. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park SY, Cho SJ, Kwon HC, Lee KR, Rhee DK, Pyo S. Caspase-independent cell death by allicin in human epithelial carcinoma cells: involvement of PKA. Cancer Lett. 2005;224:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]