Abstract

Drugs that affect microtubule dynamics, including the taxanes and vinca alkaloids, have been a mainstay in the treatment of leukemias and solid tumors for decades. New, more effective microtubule-targeting agents continue to enter into clinical trials and some, including the epothilone ixapebilone, have been approved for use. In contrast, several other drugs of this class with promising preclinical data were later shown to be ineffective or intolerable in animal models or clinical trials. In this review we discuss the molecular mechanisms as well as preclinical and clinical results for a variety of microtubule-targeting agents in various stages of development. We also offer a frank discussion of which microtubule-targeting agents are amenable to further development based on their availability, efficacy and toxic profile.

Keywords: Microtubule, Microtubule-Targeting Agent, Taxane, Vinca Alkyloid, Colchicine, Epothilone, Taccalonolide, Discodermolide, 2-Methoxyestradiol, Halichondrin B

Microtubule Structure & Dynamics

Microtubules are dynamic structures that are required for a variety of cellular processes. Microtubules, along with actin microfilaments and intermediate filaments, form the cytoskeleton. The highly organized arrangement of microtubules is required for intracellular trafficking of vesicles and organelles, cellular motility and mitotic chromosome segregation. Actin microfilaments also play an important role in mitosis, as they are required for cellular cleavage during cytokinesis.

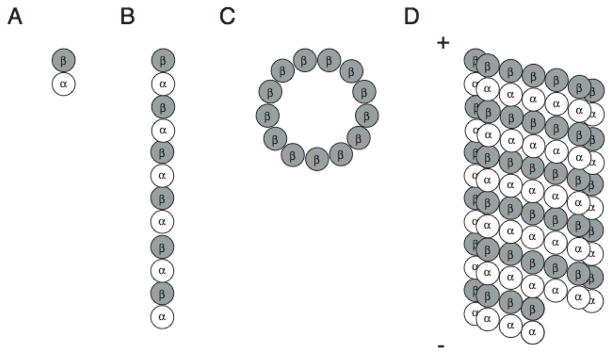

Microtubules are formed by the association of α and β-tubulin heterodimers that are folded and unfolded by chaperones as a heterodimer complex 1. These heterodimers assemble head-to-tail into linear protofilaments that further polymerize to give rise to the characteristic hollow microtubule cylinder with internal and external diameters of 12nm and 25nm respectively 2 (Figure 1). This final structure is organized in a polar manner such that the α-tubulin subunit is exposed at one end (the minus end) while the β-tubulin subunit is exposed at the other (the plus end). GTP binding and hydrolysis on β-tubulin largely dictates the stability of the microtubule polymer at the more dynamic plus end. There are two GTP binding sites on tubulin, a hydrolyzable site on the β subunit and a non-hydrolyzable site on the α-subunit. The β-tubulin subunit must be bound to GTP at the hydrolyzable site for assembly into microtubules, shortly after which the GTP is irreversibly hydrolyzed to GDP. Thus, the majority of β-tubulin in the microtubule fiber is in the GDP-bound form and “capped” with GTP-bound β-tubulin at the plus end. When the GTP on a β-tubulin molecule is hydrolyzed to GDP before another GTP-bound β-tubulin is added, the exposed GDP-β-tubulin leads to a conformational change that results in rapid depolymerization of the microtubule in an event known as microtubule catastrophe. The relatively rapid lengthening and shortening at the microtubule plus end is referred to as dynamic instability. In contrast, a more controlled loss of tubulin subunits from the minus end and gain of tubulin subunits to the plus end with no net change in microtubule mass is termed treadmilling. Microtubule associated proteins (MAPs) and microtubule-interacting drugs can promote or inhibit microtubule catastrophe as well as affect the rate of microtubule growth and shortening 3.

Figure 1.

Microtubule structure. (A) Tubulin heterodimers are composed of α and β subunits that polymerize head-to-tail to form protofilaments (B). Thirteen protofilaments form lateral contacts to create the hollow cylindrical structure of the microtubule (C and D) with β-tubulin exposed at the microtubule plus end (+) and α-tubulin exposed at the microtubule minus end (−).

Microtubule dynamics play a large role in the process of mitosis. During the majority of the cell cycle, microtubules form an intracellular lattice-like structure. However, when cells enter mitosis, this microtubule network is reorganized into the mitotic spindle. The processes of depolymerizing the interphase microtubule structure and forming the mitotic spindle, as well as finding, attaching and separating chromosomes, require highly coordinated microtubule dynamics 4. Therefore, agents that interfere with microtubule dynamics inhibit the ability of cells to successfully complete mitosis thus limiting proliferation.

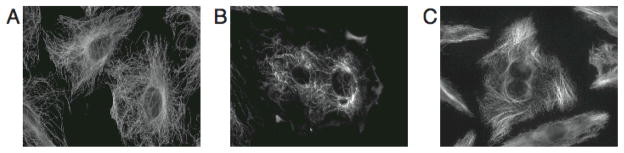

Drugs that inhibit microtubule dynamics have been used in the clinic as anti-cancer drugs for over twenty years. These drugs bind to tubulin and at high concentrations cause an increase or decrease in the interphase microtubule mass. These compounds are classified as microtubule stabilizers or destabilizers respectively (Figure 2). However, it has been shown that at lower, clinically relevant concentrations, both classes of drugs inhibit mitosis through a similar mechanism of slowing microtubule dynamics, resulting in mitotic arrest and apoptosis 5, 6. Although microtubule-targeting agents have enjoyed great clinical success as chemotherapeutics, there remain significant downfalls to their use including innate and acquired drug resistance. As a result, new agents that target microtubule dynamics are continually being sought out.

Figure 2.

The effect of microtubule-targeting agents on interphase microtubules. A10 cells were treated with vehicle (A), 250 nM vinblastine (B) or 2μM paclitaxel (C) for 18 hours. Microtubules were visualized by indirect immunofluorescence.

Microtubule Destabilizers

Vinca site-binding agents

The vinca alkaloids, isolated from the periwinkle plant, Catharanthus roseus, are potent microtubule destabilizing agents that were first recognized for their myelosuppressive effects 7. The original members of this family to undergo clinical development, vinblastine (Velban®) and vincristine (Oncovin®), were introduced into the clinic in the late 1950’s. Second-generation semi-synthetic vinca analogs, including vindesine (Eldisine®), vinorelbine (Navelbine®) and vinflunine, have been developed and are used in the treatment of a variety of cancers.

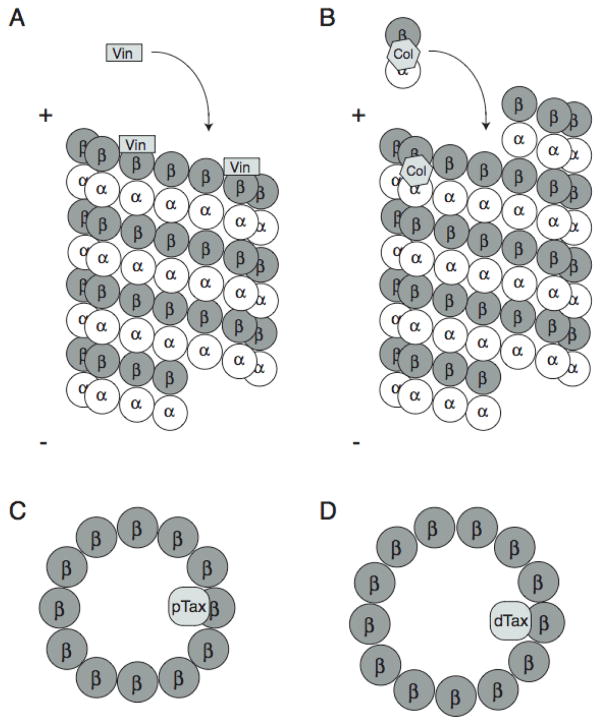

The vinca alkaloids bind to β-tubulin near the GTP binding site 8, 9. At low, clinically relevant concentrations, this binding occurs at the exposed microtubule plus end, resulting in decreased dynamics and mitotic arrest 10 (Figure 3). Thus, the vincas are sometimes referred to as “end poisons”. In contrast, the gross effect of microtubule destabilization is observed when sufficient drug is present to bind and disrupt tubulin interactions along the surface of the microtubule (Figure 2). The vincas also have affinity to free tubulin heterodimers and can give rise to tubulin paracrystals at high concentrations 11. While tubulin binding and suppression of microtubule dynamics are credited for the antineoplastic properties of the vinca alkaloids, these properties also lead to many of the observed side effects of these agents.

Figure 3.

Binding sites for microtubule-targeting agents. (A) Vinblastine (Vin) binds toβ-tubulin near the GTP-binding site at the plus end of microtubules. (B) Colchicine (Col) binds unpolymerized tubulin at the α/β-tubulin interface near the α-tubulin GTP-binding site and is then incorporated into microtubules. The binding of either vinblastine or colchicine to microtubule plus-end decreases microtubule dynamicity. At higher concentrations, binding of these drugs along the length of microtubules disrupts lateral contacts between protofilaments, resulting in gross microtubule depolymerization. (C and D) Paclitaxel (pTax) and docetaxel (dTax) bind to the interior lumen of microtubules, resulting in decreased dynamicity at low concentrations and microtubule bundling at higher concentrations. Paclitaxel and docetaxel catalyze formation of microtubules containing 12 and 13 protofilaments respectively.

Although the structures of the various vinca alkaloids vary only slightly, they have distinct niches as chemotherapeutic agents. Vincristine is most effective in the curative treatment in leukemias, lymphomas and sarcomas. A liposomal sphingosomal vincristine sulfate formulation (Marqibo®; Tekmira), which may offer more favorable pharmacokinetic properties and result in increased antitumor activity, is currently in clinical trials and has shown activity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia 12, 13. Vinblastine, which differs from vincristine only by substitution of a formyl for a methyl group, is effective in advanced testicular cancer, Hodgkin’s disease and lymphoma. Vinorelbine is currently used to treat non-small cell lung cancer as a single agent or in combination with cisplatin. In addition, clinical trials for vinorelbine are currently being conducted for metastatic breast cancer, advanced ovarian carcinoma and lymphoma 13. A sphingosomal vinorelbine formulation (Alocrest®; Tekmira), developed to increase stability and efficacy, is currently undergoing analysis in the clinic 14. Vindesine is undergoing clinical trials, primarily for treatment of acute lymphocytic leukemia 13. Vinfluine, the newest member of the vinca alkaloid family, has shown better efficacy than vinblastine in a variety of tumors and is currently in clinical trials to test for activity against solid tumors 15. The dose limiting toxicities of this class of drugs also varies with structure; neurotoxicity is the common dose-limiting toxicity associated with vincristine treatment, while neutropenia is often the most serious side effect of treatment with the other vinca alkaloids.

Halichondrin B, a macrolide lactone polyether, was isolated as a microtubule depolymerizer from several species of marine sponges. Although unique in structure from the vinca alkaloids, halichondrin B noncompetitively inhibits vinca-alkaloid binding to tubulin through an allosteric interaction 16. Therefore, the “vinca domain” is made up of both the vinca-binding site and the peptide-binding site 17. Clinically useful quantities of halichondrin B have notoriously been very difficult to isolate or synthesize. However, Eisai has developed several structurally simplified synthetic derivatives. One halichondrin derivative, E7389 (Eribulin®; Eisai), is currently in phase I trials as single agent or in combination with carboplatin, cisplatin or gemcitabine (Gemzar®; Lilly) against solid tumors 13. Phase II trials for E7389 are also underway for indications including sarcomas, gynecological tumors, head and neck tumors, non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer and prostate cancer. A phase III trial is in progress comparing E7389 to capecitabine (Xeloda®) in breast cancer 13.

There are a number of naturally occurring microtubule depolymerizing peptides, including hemiasterlin and dolastatins 10 and 15, which have been found to exert microtubule-destabilizing effects by binding at or near the vinca-binding site on tubulin. One synthetic hemiasterlin derivative from Eisai, E7974, is undergoing phase I trials against solid tumors while another, HTI-286, has shown preclinical activity against bladder cancer 13, 18. Dolstatin 10 as single agent was dropped from clinical trials due to lack of efficacy in multiple clinical trials 19–22. A synthetic analog of dolastatin 15, cemadotin, failed to advance through clinical trials due to severe cardiac toxicity 21, 23. A water soluble and metabolically stable cemadotin derivative, tasidotin (TZT-1027; Genzyme), has shown limited success in solid tumors when administered intravenously 24. However, the low toxicity profile of tasidotin combined with its water solubility has made it a candidate for additional testing as an oral formulation. Recent in vitro studies suggest that tasidotin may also have activity against childhood sarcomas 25. Cryptophycin, a depsipeptide of fresh water origin, is a very potent (pM) microtubule depolymerizer that competes with vinca binding and retains efficacy in multidrug resistant tumors 26, 27. A synthetic cryptophycin derivative, cryptophycin 52 (LY355703), entered and failed in clinical trials due to the absence of measurable responses and unacceptable toxicity 28.

Colchicine site-binding agents

Colchicine, another microtubule depolymerizing agent isolated from nature, binds to a different site on tubulin at the interface of the α/β-tubulin heterodimer, adjacent to the GTP-binding site of α-tubulin 29. Colchicine preferentially binds to unpolymerized tubulin heterodimers in solution, forming a stable complex that effectively inhibits microtubule dynamics upon binding to microtubule ends 30 (Figure 3). Colchicine causes microtubule depolymerization by inhibiting lateral contacts between protofilaments 31. Although colchicine is a potent microtubule depolymerizer with antimitotic properties, its severe toxicities at the doses required for antitumor effects have curtailed any therapeutic development as an anti-cancer agent. However, the immunomodulating properties of lower doses of colchicine are useful in the treatment of gout 32.

In spite of the severe toxicity associated with colchicines, several colchicines site-binding agents are in clinical development. One of these agents is combretastatin in the form of the disodium phosphate prodrug combretastatin A-4-phosphate (CA4P) 33. One marked advantage of CA4P is its demonstrated ability to selectively target and disrupt tumor vasculature within six hours of treatment 34. This is hypothesized to occur through depolymerization of interphase microtubules in tumor vascular endothelial cells with little effect on established normal vasculature 35, 36. Although vascular disrupting agents effectively eliminate the core of the tumor, their inability to eliminate the outer shell of the tumor requires that they be used in combination with other agents 37. Combinations of CA4P with paclitaxel, carboplatin or bevacizumab (Avastin®; Genentech) are currently being evaluated in clinical trials against solid tumors 13, 38, 39. Although the issue of toxicity remains paramount 40, the multifactoral anticancer properties of the combretastatins have prompted their further clinical evaluation.

An orally bioavailable microtubule depolymerizer that binds to the colchicine site and circumvents Pgp mediated drug resistance is ABT-751 (Abbott). Xenograft studies have shown that ABT-751 is effective against solid tumors through antimitotic and vascular disrupting activities and that it has additive effects when used in combination with other cytotoxic therapies 41, 42. ABT-751 has also been shown to have activity in a distinct subset of pediatric tumor models that are refractory to treatment with the vinca alkaloids, including neuroblastoma and Wilms tumor 43. Clinical trials looking at the effects of ABT-751 in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and solid tumors, including neuroblastoma, are in progress 13, 44, 45.

Two other colchicines site-binding drugs that breakdown tumor vasculature are NPI-2358 (Nereus) and SSR97225 (Sanofi-Aventis). The results of a phase I study for NPI-2358, presented at AACR in April 2008, indicated good tolerability in patients with solid tumors or lymphoma. Mechanistic studies suggested that tumor blood flow was inhibited 46. Additional phase I studies are underway to determine optimal dosing of NPI-2358 both as a single agent and in combination with docetaxel. SSR97225 is also undergoing early clinical development 13.

2-Methoxyestradiol (2ME2; Panzem®; Entremed) is another colchicine site-binding microtubule depolymerizing agent. Although 2ME2 is an estrogen metabolite, it does not effectively bind estrogen receptors and its antimitotic properties are independent of cellular estrogen receptor status 47. 2ME2 has been evaluated in clinical trials for multiple myloma, glioblastoma, prostate, breast and ovarian cancers. Attractive and unique properties of 2ME2 include inhibition of angiogenesis and the existence of an orally available formulation 48, 49. However, pharmakodynamic studies in phase I clinical trials have demonstrated that the bioavailability of 2ME2 is low, presumably due to metabolism to another estrogenic agent, 2-methoxyestrone (2ME1) 50, 51. ENMD-1198 (Entremed), a 2ME2 analog with improved metabolic stability, is undergoing phase I studies in advanced solid tumors 52, 53. Preclinical studies looking at the effect of 2ME2 in rheumatoid arthritis are ongoing 54. Locus pharmaceuticals is currently developing a drug candidate, LP-261, that binds competitively at the colchicine binding site 55. Like 2ME2, LP-261 is an orally bioavailable agent with both antimitotic and antiangiogenic properties. The efficacy and low toxicity in preclinical studies have advanced the development of LP-261 in phase I studies of solid tumors.

Microtubule Stabilizers

Taxane site-binding agents

The third of the well-characterized drug-binding sites on tubulin/microtubules is the taxane-binding site. The taxanes are microtubule-targeting agents that bind to polymerized microtubules within the lumen of the polymer (Figure 3). They stabilize GDP-bound β-tubulin protofilaments by straightening them into a conformation resembling the more stable GTP-bound structure 56. Interestingly, one taxane, paclitaxel (Taxol®, Bristol-Myers Squibb), has been shown to induce the formation of microtubules containing 12 protofilaments as opposed to the typical 13 57 (Figure 3). Taxane binding results in a shift of in equilibrium of tubulin heterodimers from the soluble to the polymerized form, resulting in bundling of interphase microtubules 58 (Figure 2). At lower, clinically relevant concentrations, the taxanes share a similar mechanism with vinca and colchicine site-binding agents in that they decrease microtubule dynamicity, resulting in aberrant mitotic spindle formation, mitotic arrest and initiation of apoptosis 5, 6.

Paclitaxel and its semi-synthetic analog docetaxel (Taxotere®, Sanofi-Aventis) have become a mainstay in the treatment of solid tumors, including breast and ovarian cancer 59. Although the taxanes have shared clinical success for many years, serious limitations of these drugs include the dose-limiting toxicities of immunosupression and peripheral neuropathy as well as inherent and acquired drug resistance. The most well established, clinically relevant form of taxane resistance is overexpression of the P-glycoprotein ATP-binding cassette (ABC) drug transporter (Pgp). Intrinsic overexpression of Pgp in the liver, kidney and intestinal tract has limited the use of the taxanes and other Pgp substrates in tumors derived from those tissues 60. Additionally, elevated Pgp levels have been correlated with poor clinical response in breast and non-small cell lung cancer 61, 62. Taxane treatment has been associated with increased in Pgp expression, leading to acquired resistance in both the preclinical and clinical setting 60, 63. Although there have been significant efforts to increase the efficacy of Pgp substrates through combination therapy with Pgp inhibitors, this approach has yet to yield clinical success. Another clinically relevant mechanism of taxane resistance is overexpression of the βIII isotype of tubulin, which is normally found specifically expressed in neuronal tissues 64. Studies with otherwise isogenic cell lines show that elevated levels of βIII-tubulin cause resistance to both taxane- and vinca-site binding agents 65. Although it has been suggested that mutations in the tubulin-binding site are correlated with taxane resistance, this original observation has not been reproduced in further studies, suggesting that it may not be clinically relevant 66. Several taxane-based formulations and novel taxane-binding agents that have decreased toxicity, increased tumor delivery or decreased sensitivity to Pgp-mediated resistance are currently progressing through the clinic.

One serious problem in the development of the taxanes is their poor solubility. This property necessitated their formulation in cremophor, an agent that causes hypersensitivity reactions and requires patient pretreatment. Abraxane® (Abraxis) is a paclitaxel derivative that has an increased intrinsic solubility conferred by the conjugation of albumin to paclitaxel, eliminating the requirement for cremophor. The increased solubility of Abraxane® dramatically decreases the time required for drug administration from 3 hours to 30 minutes 67. Abraxane® is currently approved for use in metastatic breast cancer after failure with anthracyclines and is undergoing further clinical trials against a myriad of other solid tumors 13. ANG1005 (Angiochem) is another modified form of paclitaxel that circumvents the use of cremophor. The unique feature of ANG1005 is that it consists of paclitaxel molecules conjugated to a receptor-targeting peptide that allows selective transport across the blood-brain barrier 68. Upon entry into cells, ANG1005 undergoes esterase cleavage to release three paclitaxel molecules from each receptor peptide. ANG1005 has shown efficacy against intracerebral tumors in mice and is currently in early stage clinical trials in recurrent glioblastoma and brain metastasis 13, 69.

XRP9881 (Larotaxel®; Sanofi-Aventis) and TPI287 (Tapestry) are semi-synthetic paclitaxel derivatives that are poor substrates for the Pgp multidrug transporter, circumventing this common mechanism of taxane resistance 70, 71. Larotaxel® is currently in phase II trials in Her2+ breast cancer as a single agent or in combination with trastuzumab (Herceptin®) 13. Separate studies are in progress looking at the effects of Larotaxel® with capecitabine (Xeloda®) in metastatic breast cancer. The effect of Larotaxel® used in combination therapy with cisplatin in non-small cell lung cancer is also being investigated 72. TPI287, an orally active agent, is in the early stages of phase II trials as a single agent in prostate and pancreatic cancer 13. Studies in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s disease are also underway.

Epothilones

The epothilones are microtubule stabilizers of myxo-bacterial origin, making them conducive to large-scale culture and isolation. Although the epothilones compete with paclitaxel binding, they appear to have a unique pharmacophore that binds at or near the taxane binding site, resulting in a similar but slightly distinct mechanism of action 73. Studies demonstrating the ability of epothilone B, but not paclitaxel, to promote assembly of purified yeast tubulin further suggests a novel mechanism of action for the epothilones 74. In addition to ease of production, an attractive feature of the epothilones is the fact that they are poor substrates for Pgp-mediated export, resulting in efficacy in a significant subset of taxane resistant tumors 75. Several epothilone derivatives are in clinical development with over 100 separate trials in progress against solid tumors and lymphoma both as single agent therapy and in combination with other agents. A semi-synthetic epothilone derivative, ixabepilone (Ixempra®; Bristol-Meyers Squibb), was approved in the fall of 2007 for metastatic or locally advanced taxane- and anthracycline-resistant breast cancer 76. Phase II studies examining the effect of Ixabepilone in chemotherapy-resistant lymphoma are also ongoing 13. Other epothilones progressing through clinical development include epothilone B (Patupilone®), ZK-EPO (Sagopilone®; Bayer) and KOS-1584 (Kosan Biosciences) 13, 77–80. In spite of the efficacy of ixabepilone in previously unresponsive tumors, peripheral neuropathy remains a significant dose-limiting toxicity in approximately 65% of treated patients 81.

A number of microtubule stabilizers of marine origin have been identified that bind at or near the taxane-binding site, including discodermolide, dictyostatin, eleutherobin and the sarcodictyins. Discodermolide (XAA296) entered phase I trials as a result of promising preclinical data, including efficacy in taxane-resistant Pgp-expressing tumors. Synergistic effects between paclitaxel and discodermolide were also observed both in vitro and in vivo 82, 83. Optimal dosing conditions with favorable pharmacokinetics were found in phase I clinical studies. However, an unanticipated side effect of severe pulmonary toxicity was observed and further clinical development was suspended 84. The limited natural supply and difficult synthesis has preempted in vivo analysis of dictyostatin, which appears to be a cyclic analog of and share microtubule contacts with discodermolide 85, 86. Eleutherobin and the sarcodictyins have not been pursued clinically likely due to their susceptibility to Pgp mediated transport 87.

Laulimalide & Peloruside A

Laulimalide (fijianolide) is a microtubule stabilizer of marine origin that has a novel microtubule-binding site on tubulin, allowing for synergism with the taxanes 88, 89. Additional advantages of laulimalide include efficacy in Pgp-expressing cell lines and potential anti-angiogenic activity 90, 91. Although notoriously difficult to synthesize, sufficient quantities of laulimalide were recently synthesized for in vivo studies. In contrast to efficacy in cancer cell lines, laulimalide demonstrated minimal tumor inhibition and severe toxicity in vivo, limiting its potential clinical usefulness 92. However, another study demonstrated the efficacy of laulimalide in the human colon model HCT-116 both in vitro and in vivo 93. A number of simplified laulimalide analogs have been synthesized that retain the antimitotic activity of laulimalide while offering increased stability 94.

Peloruside A shares many of the same properties of laulimalide, including its binding-site and synergistic effects with the taxanes 95, 96. The tolerability and in vivo efficacy of peloruside A in xenograft models of non-small cell lung cancer and Pgp-expressing breast cancer was presented at the Molecular Targets meeting in 2004 97. Reata Pharmaceuticals licensed the rights to peloruside A (RTA 301) in 2005 as a member of their preclinical development program 98.

Taccalonolides

The taccalonolides, plant-derived natural steroids, are novel microtubule stabilizers that fail to bind to or enhance polymerization of purified tubulin, suggesting a distinct mechanism of action compared with all other microtubule-targeting agents 99. The taccalonolides have many of the same effects on cells as the taxanes, including bundling of interphase microtubules and mitotic arrest with multiple aberrant spindles 100. Recent studies have demonstrated efficacy of the taccalonolides in Pgp-expressing, taxane resistant cell lines and tumors 65. Additionally, unlike paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinblastine and epothilone B, the taccalonolides are effective in βIII tubulin expressing cell lines 65. The unique structural and mechanistic properties of the taccalonolides, along with their ability to circumvent multiple modes of clinically relevant taxane resistance, support continued efforts to explore this group of compounds.

Conclusions

Microtubule targeting agents are actively used in the clinic against a wide variety of solid tumors and hematological malignancies. However, many obstacles to effective treatment with currently approved agents are present. These include inherited and acquired resistance, side effects of peripheral neuropathy and neutropenia, and poor solubility, necessitating the use of toxic solvents. The many microtubule stabilizers and depolymerizers in preclinical and clinical development will likely yield a subset of agents that will have advantages over the current standard of care in defined settings. The demonstrated synergistic effects of these novel agents with current therapies may also allow for their use at more tolerated doses.

Acknowledgments

Grant support was provided by National Cancer Institute CA121138 (SLM), the NCI P30 CA054174 and the Institute for Drug Development AT&T Endowed Chair.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no financial or personal relationships to disclose.

References

- 1.Lopez-Fanarraga M, Avila J, Guasch A, Coll M, Zabala JC. Review: postchaperonin tubulin folding cofactors and their role in microtubule dynamics. J Struct Biol. 2001;135(2):219–29. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nogales E, Wang HW. Structural mechanisms underlying nucleotide-dependent self-assembly of tubulin and its relatives. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16(2):221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan MA, Kamath K. How do microtubule-targeted drugs work? An overview. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7(8):730–42. doi: 10.2174/156800907783220417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rusan NM, Fagerstrom CJ, Yvon AM, Wadsworth P. Cell cycle-dependent changes in microtubule dynamics in living cells expressing green fluorescent protein-alpha tubulin. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(4):971–80. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okouneva T, Hill BT, Wilson L, Jordan MA. The effects of vinflunine, vinorelbine, and vinblastine on centromere dynamics. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2(5):427–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelling J, Sullivan K, Wilson L, Jordan MA. Suppression of centromere dynamics by Taxol in living osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63(11):2794–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutts JH, Beer CT, Noble RL. Biological properties of Vincaleukoblastine, an alkaloid in Vinca rosea Linn, with reference to its antitumor action. Cancer Res. 1960;20:1023–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gigant B, Wang C, Ravelli RB, et al. Structural basis for the regulation of tubulin by vinblastine. Nature. 2005;435(7041):519–22. doi: 10.1038/nature03566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin CM, Hamel E. Effects of inhibitors of tubulin polymerization on GTP hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1981;256(17):9242–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toso RJ, Jordan MA, Farrell KW, Matsumoto B, Wilson L. Kinetic stabilization of microtubule dynamic instability in vitro by vinblastine. Biochemistry. 1993;32(5):1285–93. doi: 10.1021/bi00056a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takanari H, Yosida T, Morita J, Izutsu K, Ito T. Instability of pleomorphic tubulin paracrystals artificially induced by Vinca alkaloids in tissue-cultured cells. Biol Cell. 1990;70(1–2):83–90. doi: 10.1016/0248-4900(90)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas DA. American Society of Hemotology. Atlanta, GA: 2007. Safety and Efficacy of Marquibo (Vincristine Sulfate Liopsomes Injection, OPISOME (TM)) for the Treatment of Audults with Relapsed or Refractory Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical Trials.gov. National Institutes of Health. 2008 http://clinicaltrials.gov.

- 14.Product Pipeline. Tekmira Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2008. www.tekmirapharm.com/programs/pipeline.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun-san Yip A, Yuen-Yuen Ong E, Chow LW. Vinfluine: clinical perspectives of an emerging anticancer agent. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17(4):583–591. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dabydeen DA, Burnett JC, Bai R, et al. Comparison of the activities of the truncated halichondrin B analog NSC 707389 (E7389) with those of the parent compound and a proposed binding site on tubulin. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(6):1866–75. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai RL, Pettit GR, Hamel E. Binding of dolastatin 10 to tubulin at a distinct site for peptide antimitotic agents near the exchangeable nucleotide and vinca alkaloid sites. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(28):17141–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadaschik BA, Adomat H, Fazli L, et al. Intravesical chemotherapy of high-grade bladder cancer with HTI-286, a synthetic analogue of the marine sponge product hemiasterlin. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1510–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margolin K, Longmate J, Synold TW, et al. Dolastatin-10 in metastatic melanoma: a phase II and pharmokinetic trial of the California Cancer Consortium. Investigational New Drugs. 2001;19:335–340. doi: 10.1023/a:1010626230081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaishampayan U, Glode M, Du W, et al. Phase II study of dolastatin-10 in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(11):4205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman MA, Blessing JA, Lentz SS. A phase II trial of dolastatin-10 in recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89(1):95–8. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krug LM, Miller VA, Kalemkerian GP, et al. Phase II study of dolastatin-10 in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(2):227–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1008349209956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mross K, Berdel WE, Fiebig HH, et al. Clinical and pharmacologic phase I study of Cemadotin-HCl ( LU103793), a novel antimitotic peptide, given as 24-hour infusion in patients with advanced cancer. A study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO) Phase I Group and Arbeitsgruppe Pharmakologie in der Onkologie und Haematologie (APOH) Group of the German Cancer Society. Ann Oncol. 1998;9(12):1323–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1008430515881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mita AC, Hammond LA, Bonate PL, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of tasidotin hydrochloride (ILX651), a third-generation dolastatin-15 analogue, administered weekly for 3 weeks every 28 days in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(17):5207–15. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg V, Zhang W, Gidwani P, Kim M, Kolb EA. Preclinical analysis of tasidotin HCl in Ewing’s sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(18 Pt 1):5446–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CD, Zhang X, Mooberry SL, Patterson GM, Moore RE. Cryptophycin: a new antimicrotubule agent active against drug-resistant cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54(14):3779–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith CD, Zhang X. Mechanism of action cryptophycin. Interaction with the Vinca alkaloid domain of tubulin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(11):6192–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edelman MJ, Gandara DR, Hausner P, et al. Phase 2 study of cryptophycin 52 ( LY355703) in patients previously treated with platinum based chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;39(2):197–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravelli RB, Gigant B, Curmi PA, et al. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature. 2004;428(6979):198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brossi A, Yeh HJ, Chrzanowska M, et al. Colchicine and its analogues: recent findings. Med Res Rev. 1988;8(1):77–94. doi: 10.1002/med.2610080105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharyya B, Panda D, Gupta S, Banerjee M. Anti-mitotic activity of colchicine and the structural basis for its interaction with tubulin. Med Res Rev. 2008;28(1):155–83. doi: 10.1002/med.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ben-Chetrit E, Levy M. Colchicine: 1998 update. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;28(1):48–59. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(98)80028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanthou C, Tozer GM. Tumour targeting by microtubule-depolymerizing vascular disrupting agents. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11(11):1443–57. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.11.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooney MM, van Heeckeren W, Bhakta S, Ortiz J, Remick SC. Drug insight: vascular disrupting agents and angiogenesis--novel approaches for drug delivery. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3(12):682–92. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tozer GM, Prise VE, Wilson J, et al. Combretastatin A-4 phosphate as a tumor vascular-targeting agent: early effects in tumors and normal tissues. Cancer Res. 1999;59(7):1626–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanthou C, Tozer GM. The tumor vascular targeting agent combretastatin A-4-phosphate induces reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and early membrane blebbing in human endothelial cells. Blood. 2002;99(6):2060–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siemann DW, Mercer E, Lepler S, Rojiani AM. Vascular targeting agents enhance chemotherapeutic agent activities in solid tumor therapy. Int J Cancer. 2002;99(1):1–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young SL, Chaplin DJ. Combretastatin A4 phosphate: background and current clinical status. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13(9):1171–82. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.9.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West CM, Price P. Combretastatin A4 Phosphate. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15(3):179–187. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooney MM, Radivoyevitch T, Dowlati A, et al. Cardiovascular safety profile of combretastatin a4 phosphate in a single-dose phase I study in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(1 Pt 1):96–100. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segreti JA, Polakowski JS, Koch KA, et al. Tumor selective antivascular effects of the novel antimitotic compound ABT-751: an in vivo rat regional hemodynamic study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;54(3):273–81. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jorgensen TJ, Tian H, Joseph IB, Menon K, Frost D. Chemosensitization and radiosensitization of human lung and colon cancers by antimitotic agent, ABT-751, in athymic murine xenograft models of subcutaneous tumor growth. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59(6):725–32. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morton CL, Favours EG, Mercer KS, et al. Evaluation of ABT-751 against childhood cancer models in vivo. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25(4):285–95. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yee KW, Hagey A, Verstovsek S, et al. Phase 1 study of ABT-751, a novel microtubule inhibitor, in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(18):6615–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fox E, Maris JM, Widemann BC, et al. A phase I study of ABT-751, an orally bioavailable tubulin inhibitor, administered daily for 21 days every 28 days in pediatric patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(4):1111–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mita M. Phase I Dose Escalation Trial with DCE-MRI Imaging of the Novel Vascular Disrupting Agent NPI-2358. AACR; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.LaVallee TM, Zhan XH, Herbstritt CJ, et al. 2-Methoxyestradiol inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis independently of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Cancer Res. 2002;62(13):3691–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mabjeesh NJ, Escuin D, LaVallee TM, et al. 2ME2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis by disrupting microtubules and dysregulating HIF. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(4):363–75. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fotsis T, Zhang Y, Pepper MS, et al. The endogenous oestrogen metabolite 2-methoxyoestradiol inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses tumour growth. Nature. 1994;368(6468):237–9. doi: 10.1038/368237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dahut WL, Lakhani NJ, Gulley JL, et al. Phase I clinical trial of oral 2-methoxyestradiol, an antiangiogenic and apoptotic agent, in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5(1):22–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.1.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.James J, Murry DJ, Treston AM, et al. Phase I safety, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of 2-methoxyestradiol alone or in combination with docetaxel in patients with locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25(1):41–8. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-9008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ENMD-1198. Entremed. 2008 www.entremed.com/science/enmd-1198.

- 53.Lavallee TM, Burke PA, Swartz GM, et al. Significant antitumor activity in vivo following treatment with the microtubule agent ENMD-1198. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(6):1472–82. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panzem® (2ME2) for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Entremed. 2008 www.entremed.com/science/panzem.

- 55.LP-251. Locus Pharmaceuticals; 2008. http://www.locuspharmaceuticals.com/programs/lp-261. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elie-Caille C, Severin F, Helenius J, et al. Straight GDP-Tubulin Protofilaments Form in the Presence of Taxol. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1765–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andru JM, Bordas J, Diaz JF, et al. Low Resolution structure of microtubules in solution. Synchrotron X-ray scattering and electron microscopy of taxol-induced microtubules assembled from purified tubulin in comparison with glycerol and MAP-induced microtubules. J Mol Biol. 1992;226(1):169–184. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao S, He L, Chakravarty S, et al. Characterization of the Taxol binding site on the microtubule. Identification of Arg(282) in beta-tubulin as the site of photoincorporation of a 7-benzophenone analogue of Taxol. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(53):37990–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montero A, Fossella F, Hortobagyi G, Valero V. Docetaxel for treatment of solid tumours: a systematic review of clinical data. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(4):229–39. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leonard GD, Fojo T, Bates SE. The role of ABC transporters in clinical practice. Oncologist. 2003;8(5):411–24. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-5-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trock BJ, Leonessa F, Clarke R. Multidrug resistance in breast cancer: a meta-analysis of MDR1/gp170 expression and its possible functional significance. J Nat Cancer Inst. 1997;89:917–931. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.13.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chiou JF, Liang JA, Hsu WH, et al. Comparing the relationship of Taxol-based chemotherapy response with P-glycoprotein and lung resistance-related protein expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung. 2003;181(5):267–73. doi: 10.1007/s00408-003-1029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rottenberg S, Nygren AO, Pajic M, et al. Selective induction of chemotherapy resistance of mammary tumors in a conditional mouse model for hereditary breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(29):12117–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702955104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seve P, Dumontet C. Is class III beta-tubulin a predictive factor in patients receiving tubulin-binding agents? Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(2):168–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Risinger AL, Jackson EM, Polin LA, et al. The Taccalonolides: Microtubule Stabilizers that Circumvent Clinically Relevant Taxane Resistance Mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2008;68(21):8881–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orr GA, Verdier-Pinard P, McDaid H, Horwitz SB. Mechanisms of Taxol resistance related to microtubules. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7280–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, et al. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7794–803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Demeule M, Regina A, Che C, et al. Identification and design of peptides as a new drug delivery system for the brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324(3):1064–72. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Regina A, Demeule M, Che C, et al. Antitumour activity of ANG1005, a conjugate between paclitaxel and the new brain delivery vector Angiopep-2. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155(2):185–97. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dieras V, Limentani S, Romieu G, et al. Phase II multicenter study of larotaxel (XRP9881), a novel taxoid, in patients with metastatic breast cancer who previously received taxane-based therapy. Ann Oncol. 2008 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.TPI 287. Tapestry Pharmaceuticals; 2008. www.tapestrypharma.com/TPI287. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zatloukal P, Gervais R, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Randomized multicenter phase II study of larotaxel (XRP9881) in combination with cisplatin or gemcitabine as first-line chemotherapy in nonirradiable stage IIIB or stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(8):894–901. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31817e6669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kowalski RJ, Giannakakou P, Hamel E. Activities of the microtubule-stabilizing agents epothilones A and B with purified tubulin and in cells resistant to paclitaxel (Taxol(R)) J Biol Chem. 1997;272(4):2534–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bode CJ, Gupta ML, Jr, Reiff EA, et al. Epothilone and paclitaxel: unexpected differences in promoting the assembly and stabilization of yeast microtubules. Biochemistry. 2002;41(12):3870–4. doi: 10.1021/bi0121611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Altmann KH, Wartmann M, O’Reilly T. Epothilones and related structures--a new class of microtubule inhibitors with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1470(3):M79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(00)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pazdur R, Keegan P. FDA Approval for Ixabepilone. National Cancer Institute; 2007. www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/druginfo/fda-ixabepilone. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fumoleau P, Coudert B, Isambert N, Ferrant E. Novel Tubulin-Targeting Agents: Anticancer Activity and Pharmacologic Profile of Epothilones and Related Analogs. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(Supplement 5):v9–v15. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sagopilone shows promise in combating tumors. Bayer; 2008. www.research.bayer.com/edition-19/19_Epothilones.pdfx. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kosan Pipeline. Kosan Biosciences; 2008. www.kosan.com/pipeline.html. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trivedi M, Budihardjo I, Loureiro K, Reid TR, Ma JD. Epothilones: a novel class of microtubule-stabilizing drugs for the treatment of cancer. Future Oncology. 2008;4(4):483–500. doi: 10.2217/14796694.4.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Padzur R, Keegan P. Cancer topics. N.C. Institute; 2007. FDA approval for Ixabepilone. www.cancer.gov.cancertopics/druginfo/fda-ixbepilone. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martello LA, McDaid HM, Regl DL, et al. Taxol and discodermolide represent a synergistic drug combination in human carcinoma cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(5):1978–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang GS, Lopez-Barcons L, Freeze BS, et al. Potentiation of taxol efficacy and by discodermolide in ovarian carcinoma xenograft-bearing mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(1):298–304. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mita A, Lockhart A, Chen T-L, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic (PK) trial of XAA296A (discodermolide) administered every 3 wks to adult patients with advance solid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14S):2025. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Madiraju C, Edler MC, Hamel E, et al. Tubulin assembly, taxoid site binding, and cellular effects of the microtubule-stabilizing agent dictyostatin. Biochemistry. 2005;44(45):15053–63. doi: 10.1021/bi050685l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Canales A, Matesanz R, Gardner NM, et al. The Bound Conformation of Microtubule-Stabilizing Agents: NMR Insights into the Bioactive 3D Structure of Discodermolide and Dictyostatin. Chemistry. 2008;14(25):7557–7569. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Long B, Carboni J, Wasserman A, et al. Eleutherobin, a novel cytotoxic agent that induces tubulin polymerization, is similar to paclitaxel (Taxol) Cancer Res. 1998;58(6):1111–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hamel E, Day BW, Miller JH, et al. Synergistic effects of peloruside A and laulimalide with taxoid site drugs, but not with each other, on tubulin assembly. Mol Pharmacol. 2006 doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Clark EA, Hills PM, Davidson BS, Wender PA, Mooberry SL. Laulimalide and Synthetic Laulimalide Analogues Are Synergistic with Paclitaxel and 2-Methoxyestradiol. Mol Pharm. 2006;3(4):457–467. doi: 10.1021/mp060016h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lu H, Murtagh J, Schwartz EL. The microtubule binding drug laulimalide inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced human endothelial cell migration and is synergistic when combined with docetaxel (taxotere) Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69(4):1207–15. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mooberry SL, Tien G, Hernandez AH, Plubrukarn A, Davidson BS. Laulimalide and isolaulimalide, new paclitaxel-like microtubule-stabilizing agents. Cancer Res. 1999;59(3):653–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu J, Towle M, Cheng H, et al. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activities of synthetic (−)-laulimalide, a marine natural product microtubule stabilizing agent. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(3B):1509–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Johnson TA, Tenney K, Cichewicz RH, et al. Sponge-derived fijianolide polyketide class: further evaluation of their structural and cytotoxicity properties. J Med Chem. 2007;50(16):3795–803. doi: 10.1021/jm070410z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mooberry SL, Randall-Hlubek DA, Leal RM, et al. Microtubule-stabilizing agents based on designed laulimalide analogues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(23):8803–8808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402759101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wilmes A, Bargh K, Kelly C, Northcote PT, Miller JH. Peloruside A synergizes with other microtuule stabilizing agents in cultured cancer cell lines. Mol Pharm. 2007;4:269–280. doi: 10.1021/mp060101p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gaitanos TN, Buey RM, Diaz JF, et al. Peloruside A does not bind to the taxoid site on beta-tubulin and retains its activity in multidrug-resistant cell lines. Cancer Res. 2004;64(15):5063–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Meyer C, Ferguson D, Krauth M, Wick M, Northcote P. A novel microtubule stabilizer with potent in vivo activity against lung cancer and resistant breast cancer. Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics; Geneva, Switzerland. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Reata announces licencing of novel natural products with anticancer potential. Reata Pharmaceuticals; 2005. www.reatapharma.com/news_detail.asp?id=11. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Buey RM, Barasoain I, Jackson E, et al. Microtubule interactions with chemically diverse stabilizing agents: thermodynamics of binding to the Paclitaxel site predicts cytotoxicity. Chem Biol. 2005;12(12):1269–79. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tinley TL, Randall-Hlubek DA, Leal RM, et al. Taccalonolides E and A: Plant-derived steroids with microtubule-stabilizing activity. Cancer Res. 2003;63(12):3211–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]