Abstract

Female rats exhibit a conditioned place preference (CPP) for a context paired with mating. The present experiment tested the hypothesis that the activation of the pelvic nerve mediates the reinforcing effects of mating for female rats. Rats underwent bilateral pelvic nerve or sham transection and then received paced mating, nonpaced mating or the control treatment during a CPP procedure. Pelvic nerve transection did not affect the CPP for paced or nonpaced mating. In tests of paced mating behavior, contact-return latencies following intromissions were significantly shorter in rats with pelvic nerve transection than rats with sham transections. These results show that the pathway conveying the reinforcing effects of mating stimulation does not depend on the integrity of the pelvic nerve, but that activation of the pelvic nerve contributes to the display of paced mating behavior.

Keywords: pelvic nerve, sexual behavior, reinforcement, aversion, paced mating behavior

The reinforcing effects of sexual behavior in female rats have been demonstrated using the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm, a form of classical conditioning in which rats exhibit a preference for a distinctive context that has been associated with a drug or behavior, such as mating (Meerts & Clark, 2007; Paredes & Alonso, 1997; Gans & Erskine, 2003). The characteristics of the mating stimuli that contribute to the CPP have been the topic of recent investigation. Several studies have assessed the rewarding aspects of paced mating behavior, in which the female controls the timing of sexual stimulations, and nonpaced mating behavior, in which the timing of sexual stimulations is largely dependent on the male’s behavior. Paredes and Vasquez (1999) and others (Gans & Erskine, 2003; Paredes & Alonso, 1997; Martinez & Paredes, 2001) have shown that paced mating behavior is reinforcing to female rats whereas work from our laboratory has demonstrated that female rats also display a conditioned place preference for nonpaced mating behavior (Meerts & Clark, 2007). The finding of Walker and colleagues (2002) that female rats express a CPP for a context paired with a single application of vaginal lavage prompted our laboratory to explore the contribution of sensory input to the reinforcing effects of mating. Recently we reported that female rats express a CPP for a context paired with artificial vaginocervical stimulation (aVCS) administered at the rate experienced during mating (Meerts & Clark, in press). Collectively, these data indicate that vaginal and or cervical stimulation is an important component of the reinforcing effect of mating.

The pelvic region is innervated by multiple genitosensory nerves including the pelvic, hypogastric, pudendal and vagal nerves (reviewed in McKenna, 2002). The specific genitosensory pathway(s) that convey the stimulus properties of mating and aVCS that are reinforcing to female rats have not been identified; the pelvic nerve is a strong candidate because the sensory fields it innervates include the vagina and cervix (McKenna, 2002). A number of studies have examined the role of the pelvic nerve in reproductive functioning in female rats. Electrical or mechanical stimulation of the vagina or cervix activates the pelvic nerve (Berkley, Robbins, & Sato, 1993) which, in turn, relays information to brain regions including the medial preoptic area and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Chadha & Hubscher, 2008; Hubscher, 2006). In addition, pelvic neurectomy alters the expression of mating- or aVCS-induced Fos in the medial preoptic area as well as other brain regions (Pfaus, Manitt, & Coopersmith, 2006; Rowe & Erskine, 1993; Wersinger, Baum, & Erskine, 1993). Recent data also implicate the medial preoptic area in the reinforcing effects of mating in female rats (Garcia Horsman, Agmo & Paredes, 2008: Meerts and Clark, unpublished). Assessment of mating behavior has shown that the time spent with a sexually active male rat was greater in female rats with pelvic neurectomy (Emery & Whitney, 1985) and that the ability to discriminate between mounts and intromissions was impaired in rats with pelvic neurectomy compared to sham neurectomy (Erskine, 1992). Together these behavioral and anatomical data support the view that the pelvic nerve conveys information about mating stimulation to brain regions involved in mediating the reinforcing effects of mating in female rats. The present experiment tests the hypothesis that activation of the pelvic nerve is essential for the reinforcing effects of mating in female rats. As mentioned earlier, female rats exhibit a CPP for a context paired with either paced or nonpaced mating behavior (Meerts & Clark, 2007). Given that stimulus parameters such as ejaculation duration and interintromission interval can vary during different mating conditions (e.g., paced vs. nonpaced mating; Coopersmith, Candurra, & Erskine, 1996; Erskine, Kornberg, & Cherry, 1989; Meerts & Clark, 2007), the expression of a CPP for mating was examined in independent cohorts of rats receiving paced mating or nonpaced mating.

General Method

Subjects

One hundred and one virgin female Long-Evans rats weighing approximately 200 g were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). Rats were housed individually in hanging metal cages in a light (12:12-hr light/dark cycle, lights off at 1000) and temperature-controlled vivarium. Commercial rat food pellets and water were available ad lib. Experimental and control rats received 10 μg estradiol benzoate (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 48 hr and 1 mg progesterone (Sigma) 4 hr prior to each reinforced conditioning session. Hormones were administered s.c. in a sesame oil vehicle. Sexually experienced male Long-Evans rats, aged 3-4 months, served as stimulus rats. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Dartmouth College approved the use of rats in these studies and all procedures were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines. Mating tests and conditioning occurred during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle under dim red illumination and were conducted in the same room.

Surgery

Rats were randomly assigned to five treatment groups before surgery: Pelvic nerve transection (Pex) + paced mating (n = 24), Sham transection (Shx) + paced mating (n = 22), Pex+ nonpaced mating (n = 13), Shx+ nonpaced mating (n = 10), and Control (n = 32). Female rats were gonadectomized at the same time as the pelvic nerve or sham transection. The paced mating behavior groups were assigned more rats than the nonpaced mating groups because preliminary and published studies suggested the possibility of added variability in the display of paced mating following Pex (Erskine, 1992). The procedure for pelvic nerve transection is as described previously (Cunningham, Steinman, Whipple, Mayer, & Komisaruk, 1991; Erskine, 1992; Rowe & Erskine, 1993). Rats were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine mixture (50 mg/kg, Schein, Port Washington, NY). A 4-5 cm long midline incision was made in the lower abdomen. Following removal of the ovaries, the bifurcation of the vena cava into the common iliac veins was located by gentle retraction of the surrounding muscle. The pelvic nerve lies perpendicular to the internal iliac vein approximately 5 mm from its origin. Once the pelvic nerve was visualized it was lifted away from the surrounding muscle with a microsurgical hook and a 2-4 mm portion of the nerve was removed using microdissection scissors. The procedure was repeated on the contralateral side. In sham neurectomies, the nerve was visualized but not manipulated. Upon completion of neurectomy the abdominal wall and skin were closed. As recommended by the veterinary staff, all rats received daily antibiotic treatment (Baytril, 2.5 mg/kg s.c., Schein). Because pelvic nerve transection interferes with bladder emptying, urine was manually expelled twice daily by gently depressing the lower abdomen (Carlson & De Feo, 1965; Cunningham et al., 1991; Erskine, 1992; Kollar, 1953). Conditioning procedures were initiated two weeks after surgery.

Behavioral procedures

Place preference conditioning and mating tests followed procedures established in our laboratory (Meerts & Clark, 2007). The apparatus (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) consisted of three distinct compartments; the two outer compartments (28 × 21 × 21 cm high) were connected by a middle gray compartment (12 × 21 × 21 cm high) via manually-controlled sliding guillotine doors. One side compartment had white walls, was illuminated and had a metal bar floor with aspen bedding in a waste pan beneath the floor. The other side compartment had black walls, metal grid flooring and was scented with a 2% glacial acetic acid solution. Photobeams spaced at 5-cm intervals were used to record the time spent in each compartment.

During the initial 10-min baseline (pre-conditioning) place preference test, rats began in the middle compartment and freely explored the entire apparatus; the compartment in which the rat spent the majority of time on the baseline test was designated the preferred compartment. Although group assignments were made prior to surgery no treatment group differences in the preference or difference scores were present on the baseline place preference test, in addition, rats did not exhibit a significant preference for either side compartment on the baseline test.

The paced mating treatment was delivered in a clear Plexiglas arena (75 × 37.5 × 32 cm high) divided into two equally sized compartments using a clear partition (36.5 × 31.7 cm) with two 5.0-cm holes, one in each bottom corner; the holes allowed the female to travel between compartments but were too small for the male to fit through. An opaque Plexiglas partition (36.5 × 31.7 cm) adjacent to the clear partition separated the experimental female rat from the male rat prior to the start of behavioral testing. The nonpaced mating treatment was delivered in the standard Plexiglas arenas used for tests of nonpaced mating behavior in our laboratory (39.4 × 22.9 × 31.1 cm high). Aspen bedding covered the floor of each mating arena. Rats were habituated to the appropriate arena for 5 min immediately prior to the behavioral treatment.

Paced mating treatment began when the opaque partition was removed allowing the female rat access to the male compartment and concluded once the female rat received 15 intromissions, including ejaculations. If an ejaculation occurred before the 15th intromission, then the male rat was replaced after the female returned to the male compartment following the ejaculation and the test continued until the female rat received 15 cumulative intromissions. Each rat received at least one ejaculation during the tests for paced mating behavior. Experimenters recorded the number and timing of mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations as well as lordosis responses (lordosis quotient, number of lordosis responses divided by the number of mounts × 100), and frequencies of proceptive (hops, darts and ear wiggling) and rejection (kicks and defensive postures) behaviors (Beach, 1976; Erskine, 1989; Hardy & Debold, 1971; Madlafousek & Hlinak, 1977). The following measures were calculated for tests of paced mating behavior: (1) contact-return latencies, the length of time the female withdraws from the male compartment following each type of sexual stimulation, (2) percentage of exits, the rate of withdrawal from the male following each type of sexual stimulation, (3) percentage of total test time the female spent in the compartment with the male rat, (4) rate of proceptive behaviors (number/sec × 100), (5) rate of rejection behaviors (number/sec × 100), and (6) interintromission interval, defined as the mean length of time between intromissions, not including ejaculations. In addition, the difference in percentage of exits after mounts versus intromissions (% exit intromission − % exit mount) was calculated to facilitate comparison with published findings (Erskine, 1992).

In the nonpaced mating groups, treatment began when the female rat was placed into the arena with the male rat and concluded once the female rat received 15 intromissions, including ejaculations. If an ejaculation occurred before the 15th intromission, then the male rat was immediately replaced with a new male and the test continued until the female rat received 15 cumulative intromissions. The test length, number and timing of mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations as well as sexual receptivity (lordosis quotient) and the frequencies of proceptive and rejection behaviors were recorded. Four measures were calculated for tests of nonpaced mating behavior: (1) interintromission interval, (2) post-ejaculatory interval, defined as the mean length of time between an ejaculation and the next intromission, (3) rate of proceptive behaviors (number/sec × 100) and (4) rejection behaviors (number/sec × 100).

In all, each experimental rat underwent a total of 6 conditioning sessions: three reinforced and three nonreinforced sessions. All conditioning sessions lasted 30 min. On the first, third and fifth conditioning day rats received nonreinforced conditioning sessions and on the second, fourth and sixth conditioning day rats received reinforced conditioning sessions. For reinforced conditioning sessions rats were placed into the nonpreferred compartment of the CPP apparatus for 30 min immediately following the designated treatment (paced mating or nonpaced mating). For nonreinforced conditioning sessions rats were placed directly from their home cages into the preferred compartment of the CPP apparatus for 30 min. Rats in the Control group received the hormone priming according to the schedule described above for rats in the paced and nonpaced mating groups and were placed directly from their home cages into the preferred or nonpreferred compartment on nonreinforced or reinforced conditioning sessions, respectively. The walls and waste pans were wiped with distilled water after each conditioning session. Twenty-four hr after the final conditioning session the experimental rats were given a post-conditioning preference test following the same procedures outlined above for the baseline test.

At the conclusion of behavioral testing, rats received an overdose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and bladders were removed and measured: bladder distention occurs following pelvic nerve transection and is used as an index of the efficacy of pelvic nerve transection (Emery & Whitney, 1985; Erskine, 1992).

Rats were excluded from the analysis if they exhibited a preference or difference score more than 2 standard deviations from the mean on the baseline CPP test (n = 4), resulting in the final group assignments of Pex + paced mating (n = 22), Shx + paced mating (n = 22), Pex + nonpaced mating (n = 12), Shx + nonpaced mating (n = 10), and Control (n = 31).

Data analysis

The present study was designed to test the effect of pelvic nerve transection on the induction of a CPP for paced mating behavior and for nonpaced mating behavior in independent cohorts of rats. Preference for paced relative to nonpaced mating behavior was not assessed. To assess the induction of a CPP the following measures were calculated: (1) a preference score, defined as time in reinforced compartment / (time in reinforced compartment + time in nonreinforced compartment), and (2) a difference score, defined as the time in the nonreinforced compartment – time in reinforced compartment (Coria-Avila, Ouimet, Pacheco, Manzo, & Pfaus, 2005; Frye, Bayon, Pursnani, & Purdy, 1998; Meerts & Clark, 2007; Paredes & Alonso, 1997; Paredes & Vazquez, 1999). The analysis of these transformed measures, instead of the raw data, is useful because the transformed measures eliminate the potential confound of time spent in the middle gray compartment. In addition, the convention is to consider these measures in parallel because an increase in the preference score could occur because of a decrease in the time spent in the gray compartment; a corresponding decrease in the difference score ameliorates that concern (Paredes & Alonso, 1997). Paired t-tests were used to evaluate the change in preference score and difference score from the baseline to the test (Dominguez-Salazar, Camacho, & Paredes, 2008; Kohlert & Olexa, 2005; Meerts & Clark, 2007; Meisel & Joppa, 1994). The criteria for the induction of a CPP were a significant increase in the preference score in tandem with a significant decrease in the difference score (Meerts & Clark, 2007; Paredes & Alonso, 1997). The alpha level was set at 0.05.

Mating behavior data collected on the three conditioning tests were averaged for each treatment (paced mating or nonpaced mating), and the average of these measures was subjected to statistical analysis (Dominguez-Salazar et al., 2008; Garcia Horsman & Paredes, 2004). The behavioral measures from tests of paced mating behavior were analyzed using a 3 (type of sexual stimulation) × 2 (nerve transection) analysis of variance (ANOVA); these analyses were conducted only on the data from the two groups in the paced mating condition because the groups in the nonpaced mating condition did not have the opportunity to leave the compartment housing the male rat. Contact-return latencies and percentage of exits were analyzed separately to determine each measure varied as a function of type of sexual stimulation. One-way ANOVAs were conducted on measures of paced mating behavior (contact-return latencies, and percentage of exits), interintromission intervals, the numbers of stimulations (mounts, intromissions and ejaculations) received, sexual receptivity, percentage of test time with male, rate of proceptive behaviors, rate of rejection behaviors, test duration and difference in percentage of exits after intromissions versus mounts. The measures of interintromission interval, post-ejaculatory latency and rates of proceptive and rejection behaviors collected during tests of nonpaced mating behavior were also subject to one-way ANOVA. The effect of nerve transection on bladder size was assessed with ANOVA followed by post-hoc comparisons using Tukey’s test. The alpha level was set at 0.05.

Results

Place preference

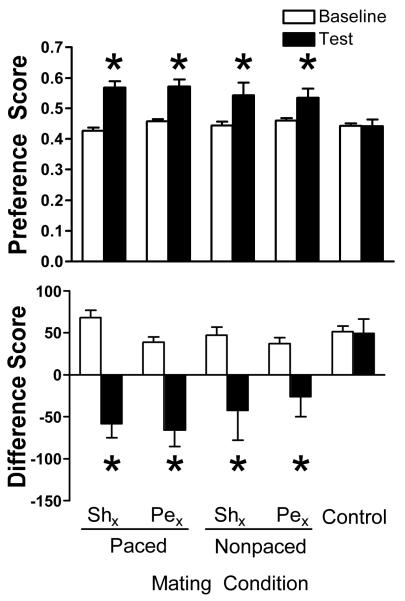

Female rats with pelvic neurectomy, like sham-operated females, showed a significant CPP for the context associated with either paced or nonpaced mating (Figure 1). Specifically, from the baseline to the test, Pex + paced mating, Shx + paced mating, Pex + nonpaced mating and Shx + nonpaced mating exhibited a significant increase in the preference score coincident with a significant reduction in the difference score (all t’s > 2.3, p < 0.05). The preference and difference scores of the rats that received the Control treatment did not change from the baseline to the test.

Figure 1.

Mean ± SEM preference (top) and difference (bottom) scores on the baseline (pre-conditioning, open bars) and test (post-conditioning, black bars) are shown for female rats that received pelvic nerve transection (Pex) or sham neurectomy (Shx) before receiving paced mating, nonpaced mating or the Control treatment. Pex + paced mating, n = 22; Shx + paced mating, n = 22; Pex + nonpaced mating, n = 12; Shx + nonpaced mating, n = 10; Control, n = 31. Rats that received paced or nonpaced mating as a treatment (with or without an intact pelvic nerve) displayed a CPP for the compartment associated with the treatment: a significant increase in preference score coincident with a significant decrease in difference score, *p < 0.05 vs. Baseline.

Paced Mating Behavior

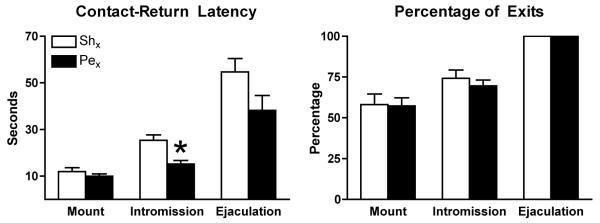

Rats displayed high levels of sexual receptivity; there were no effects of nerve transection on the lordosis quotients (Mean ± SEM lordosis quotient: Pex+ paced mating = 100 ± 0; Shx+ paced mating = 100 ± 0). Rats with sham transections displayed the normal “stair-step” pattern of responses to mating stimuli such that more intense stimuli (mount < intromission < ejaculation) elicited longer delays in approach behavior and more frequent exits from the male’s compartment (Figure 2). Pelvic nerve transection did not alter the stair-step nature of the response for either contact-return latency or percentage of exits (Figure 2), nor the number of mounts, intromissions and ejaculations received during the paced mating behavior test (data not shown). There was a significant main effect of type of sexual stimulation on contact-return latencies (F(2,125) = 46.8, p < 0.01) and a main effect of group (F(1,125) = 9.4, p < 0.01) but no interaction between type of sexual stimulation and group. Posthoc analyses revealed that following intromissions rats with pelvic neurectomy exhibited significantly shorter contact-return latencies than rats with sham transection (F(1,42) = 13.6, p < 0.01). Contact-return latencies following ejaculation were also shorter for rats with Pex versus Shx, but this difference did not attain statistical significance (F(1,42) = 2.8, p = 0.062) (Figure 2). The interintromission interval in tests of paced mating behavior did not differ significantly between rats with Pex versus Shx (Mean ± SEM secs: Pex, 34.9 ± 3.6; Shx, 41 ± 4.8). For percentage of exits, there was also a significant main effect of type of sexual stimulation (F(2,126) = 52.3, p < 0.01) but no main effect of group or interaction between type of sexual stimulation and group. Thus, rats with pelvic neurectomy and sham neurectomy withdrew from the male’s compartment with comparable frequency following the receipt of each type of sexual stimulation (Figure 2). Nerve transection did not affect the difference between percentage of exits following intromissions and the percentage of exits following mounts (Mean ± SEM % exit intromission − % exit mount: Pex, 10.4 ± 4.9; Shx, 12.9 ± 6.2).

Figure 2.

Mean ± SEM contact-return latencies (left: Shx, n = 22; Pex, n = 21-22) and percentage of exits (right: Shx, n = 22; Pex, n = 22) are shown for rats with Pex (black bars) or Shx (open bars). Both contact-return latency and percentage of exits varied as a function of the type of sexual stimulation for Shx and Pex. Contact-return latencies were significantly shorter following intromissions for rats with Pex compared to rats with Shx, *p < 0.01 vs. Shx.

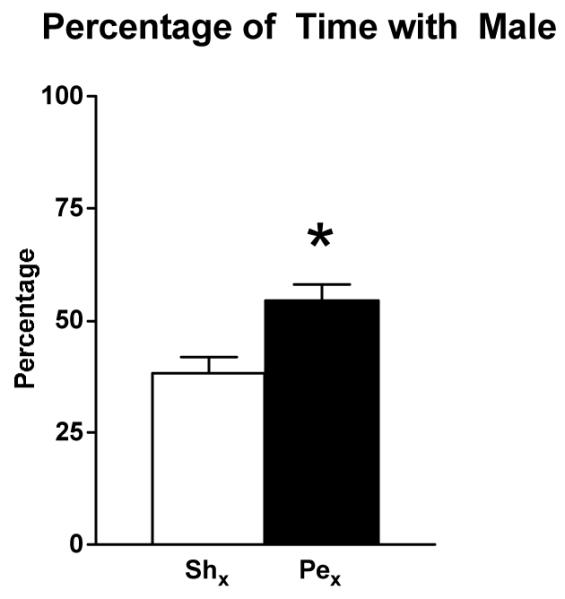

There was a significant effect of nerve transection on where the female rat spent her time during paced mating behavior tests. The percentage of test time spent with the male rat was significantly greater in rats with Pex than Shx rats (F(1,42) = 9.9, p < 0.01) (Figure 3). Nerve transection also resulted in a change in the rate at which proceptive and rejection behaviors were displayed. A higher rate of proceptive behaviors and lower rate of rejection behaviors were exhibited by Pex than Shx rats (both F’s >4.4, p <0.05) (Mean ± SEM proceptive behaviors/sec × 100: Pex, 5.2 ± 0.5; Shx, 3.3 ± 0.5; Mean ± SEM rejection behaviors/sec × 100: Pex, 0.05 ± 0.02; Shx, 0.2 ± 0.08).

Figure 3.

Mean ± SEM percentage of test time spent in the compartment with the male rat is shown for rats with Pex (black bars; n = 22) or Shx (open bars; n = 22). The percentage of time spent with the male was significantly greater in the Pex group compared to the Shx group, *p < 0.05 vs. Shx.

Nonpaced Mating Behavior

Rats exhibited high levels of sexual receptivity and there were no effects of nerve transection on lordosis quotients (Mean ± SEM lordosis quotient: Pex+ nonpaced mating, 99.75 ± .03; Shx+ nonpaced mating, 99.6 ± 0.03).

As observed for paced mating behavior, the rate of rejection behaviors exhibited during nonpaced mating was reduced in rats with Pex vs. Shx rats (F(1,20) = 6.6, p < 0.05) (Mean ± SEM rejection behaviors/sec × 100: Pex, 0.5 ± 0.2; Shx, 2.1 ± 0.6). In contrast to the findings for paced mating, pelvic neurectomy had no effect on the rate of proceptive behaviors displayed during nonpaced mating (Mean ± SEM proceptive behaviors/sec × 100: Pex, 5.9 ± 0.5; Shx, 5.8 ± 0.7). The interintromission interval in tests of nonpaced mating did not differ as a function of neurectomy (Mean ± SEM secs: Pex, 23.2 ± 2.9; Shx, 19.6 ± 1.5). Test length and the post-ejaculatory interval did not differ between Pex and Shx rats (data not shown).

Bladder length

As predicted, the bladders of rats with pelvic nerve transection were significantly distended compared with bladders from rats with sham transection or Controls (F(2,94) = 35.8, p < 0.01) (Mean ± SEM bladder length, Pex, 16 ± 0.7 mm; Shx, 11.3 ± 0.3 mm; Control, 11.2 ± 0.2 mm).

Discussion

The present study tested the hypothesis that activation of the pelvic nerve during mating is integral to the reinforcing effects of both paced and nonpaced mating. Contrary to predictions, female rats with pelvic nerve transection showed a significant CPP for the context paired with mating. Our hypothesis was based on the findings that transection of the pelvic nerve alters the expression of mating-induced c-fos expression in discrete brain areas (Pfaus et al., 2006; Rowe & Erskine, 1993; Wersinger et al., 1993) and modifies specific aspects of mating behavior (Emery & Whitney, 1985; Erskine, 1992). It is noteworthy that information about vaginocervical stimulation is communicated via the pelvic nerve (Pfaus et al., 2006; Rowe & Erskine, 1993; Wersinger et al., 1993), and it has recently been demonstrated that the delivery of vaginocervical stimulation induces a CPP in rats (Meerts & Clark, in press; Walker et al., 2002). Collectively, these data suggest that the pelvic nerve is a key relay conveying information to the central nervous system about vaginal and cervical stimulation received during a mating encounter. Even with this clear role of the pelvic nerve in transmitting vaginal and cervical stimulation to the central nervous system, it does not carry information essential for the reinforcing effects of mating.

Pelvic Nerve Transection Alters Mating Behavior

A new finding in the present study was that contact-return latencies to intromissions were significantly shorter in the Pex group versus the Shx group. Some researchers have proposed that contact-return latency is an indicator of the motivational aspects of mating, including aversive components (Blaustein & Erskine, 2002; Erskine, 1992; Johnson, 1977; Pfaff & Agmo, 2002). Peirce and Nutall (1961) were among the first to suggest that the longer contact-return latencies exhibited following intromissions and ejaculations, as opposed to mounts, indicate that sexual contacts that include vaginocervical stimulation have an aversive dimension for female rats. Considered in this context the shortened contact-return latencies to intromissions observed in rats with Pex could be viewed as evidence of diminished aversion due to dampened vaginal sensitivity (Lodder & Zeilmaker, 1976). In contrast, one study reported that the escape response elicited by vaginal distension was not moderated by pelvic neurectomy (Berkley, 1990).

Under some circumstances the receipt of vaginocervical stimulation suppresses the expression of proceptive behaviors and increases the display of rejection responses (Pfaus, Smith, Byrne, & Stephens, 2000). The observation that rats without an intact pelvic nerve spend a greater proportion of the test with the male rat, exhibit a higher rate of proceptive behaviors and a lower rate of rejection behaviors indicate that an intact pelvic nerve plays a role in the modulation of these behavioral responses. Additional research is needed to clarify the role of vaginal and cervical sensitivity in the display of the different components of mating behavior, as well as the modulation of these components by specific inputs.

Our finding that rats with pelvic nerve transection spend a greater percentage of the test time with the male reaffirms the original observations of Emery and Whitney (1985) as determined in a paradigm consisting of multiple compartments and multiple stimulus animals. Previously, Erskine (1992) reported that an intact pelvic nerve is required for the expression of differential behavioral responses to mating stimuli (mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations). To the contrary, we did not find evidence that the discrimination between mounts and intromissions was altered by pelvic nerve transection; in the present study rats with pelvic neurectomy and sham neurectomy exhibited differential contact-return latencies and percentage of exits between mounts, intromissions and ejaculations, as evidenced by the main effect of stimulation on both measures of paced mating behavior independent of nerve transection condition.

Mating Behavior and Reward

There are conflicting reports about the extent to which nonpaced mating induces a conditioned place preference (see Meerts & Clark, 2007; Paredes & Alonso, 1997; Paredes & Vasquez, 1999). Although our laboratory and others have found that female rats exhibit a conditioned place preference for a variety of mating stimuli not limited to paced mating (Jenkins & Becker, 2003; Meerts & Clark, 2007; Meerts & Clark, in press; Parada, Tecamachaltzi-Silvaran, Chamas, Coria-Avila, & Pfaus, 2008), other researchers report a conditioned place preference only in rats allowed to pace their mating contacts (Gans & Erskine, 2003; Paredes & Alonso, 1997; Martinez & Paredes, 2001). Possible reasons for these discrepancies have been suggested and await further study (Meerts & Clark, 2007). It is informative to consider that Coria-Avilla et al. (2008) comment that little more than half (60%) of the rats in their 2005 study (Coria-Avilla et al., 2005) expressed a CPP for the chamber paired with paced versus nonpaced mating. This observation is consistent with the view that there may be a continuum of reinforcing elements associated with mating encounters. The opportunity for social contact, the exposure to olfactory stimuli and the receipt of mating stimuli that occur during nonpaced mating provide reinforcement to a female rat but perhaps not as much reinforcment as the additional opportunities for solicitation behavior, the lengthened intervals between stimulations and other elements afforded during a paced mating encounter (Coria-Avilla et al., 2008; Meerts & Clark, in press). Although the present set of experiments was not designed to assess the contribution of the pelvic nerve to the relative reward value of paced vs. nonpaced mating it will be important to address this question in future studies.

The pattern of mating differs between paced and nonpaced mating conditions (Erskine, Kornberg, & Cherry, 1989) and with this in mind the present study examined whether the conditioned place preference elicited in each mating condition was dependent on the integrity of the pelvic nerve. Specifically, we hypothesized that transection of the pelvic nerve would abolish the display of a CPP to mating on the basis of studies showing an important role for the pelvic nerve in reproduction, including evidence that the pelvic nerve relays information about vaginocervical stimulation to the brain (Chadha & Hubscher, 2008; Hubscher, 2006; Pfaus et al., 2006; Rowe & Erskine, 1993; Wersinger et al., 1993) and influences the display of paced mating behavior (Emery & Whitney, 1985; Erskine, 1992). The finding that female rats with pelvic nerve transection showed a CPP for mating is consistent with the mating behaviors exhibited in rats with pelvic neurectomy. The pattern of shorter contact-return latencies, a higher percentage of the test time spent with the male rat and an increase in proceptive and a decrease in rejection behaviors following transection of the pelvic nerve signal a sexual reward circuit that is intact, not compromised.

Other Candidate Genitosensory Nerves

During a mating encounter leading to ejaculation, female rats receive flank, perineal, clitoral, vaginal and cervical contact (O’Hanlon, Meisel, & Sachs, 1981; Peters, Kristal, & Komisaruk, 1987; Pfaff & Lewis, 1974). The perigenital regions stimulated during copulation are innervated by the pelvic, hypogastric and pudendal nerves that, to some extent, have overlapping sensory regions (McKenna, 2002). The outcome of the present study indicates that the contribution(s) of the hypogastric and pudendal nerves to the reinforcing effects of mating warrant further investigation.

Long-lasting muscular contractions of the uterus are elicited within 5 min of a mating encounter (Toner & Adler, 1986). The hypogastric nerve innervates areas including the cervix and uterus (Peters et al., 1987) and is involved in the regulation of uterine contractions (Dmitrieva, Johnson, & Berkley, 2001: Sato, Hotta, Nakayama, & Suzuki, 1996). The potential co-incidence of the onset of mating-induced uterine contractions with the period of conditioning in the CPP apparatus in the present study raises the possibility that this response, which is mediated by the hypogastric nerve, is a factor in the formation of a place preference. Data showing that hypogastric neurectomy interferes with the display of an escape response to uterine distension in female rats shows that the hypogastric nerve is important for the transmission of uterine sensations (Temple, Bradshaw, Wood, & Berkley, 1999). Neuroanatomical evidence demonstrating that the expression of aVCS-induced Fos-immunoreactivity in the medial preoptic area is modified by hypogastric neurectomy also supports the view that the hypogastric nerve may relay information necessary for the display of a mating induced CPP (Pfaus et al., 2006).

The pudendal nerve that innervates the clitoris, the cutaneous areas of the flanks, and the perineum is activated by palpation of the flanks and contact with the clitoris that occurs during mating (Pacheco, Martinez-Gomez, Whipple, Beyer, & Komisaruk, 1989; Peters et al., 1987). Experiments in anesthetized rats have demonstrated that neurons in the medial preoptic area and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis respond to electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve (Chadha & Hubscher, 2008). Moreover, a recent report found that direct stimulation of the clitoris evokes a conditioned place preference in rats (Parada, Tecamachaltzi-Silvaran, Chamas, Coria-Avila, & Pfaus, 2008). These data suggest that activation of the pudendal nerve, potentially via clitoral stimulation, is involved in the generation of a CPP for mating in female rats.

The vagus nerve is also a candidate for mediating the reinforcing effects of vaginocervical stimulation because it conveys information from the uterus and cervix to the brain and mediates vaginocervical stimulation-induced analgesia (Cueva-Rolon et al., 1996; Komisaruk et al., 1996). Although combined bilateral pelvic, pudendal and hypogastric neurectomy dramatically reduced vaginocervical stimulation-induced analgesia, residual analgesic effects remained (Cueva-Rolon et al., 1996). Combining vagus nerve transection with transection of the other genitosensory nerves completely abolished vaginocervical stimulation-induced analgesia, demonstrating that brain-mediated responses to vaginocervical stimulation involve the vagus nerve (Cueva-Rolon et al., 1996). Additional experiments are required to determine the role of these nerves on the reinforcing effects of mating in female rats.

Induction of a CPP for mating might involve the concurrent stimulation of multiple genitosensory nerves. Whereas pelvic neurectomy diminished aVCS-induced analgesia as measured by tail-flick latency, combined pelvic and hypogastric neurectomy abolished aVCS-induced analgesia as measured by both tail-flick latency or vocalization threshold (Cunningham et al., 1991). Similarly, vaginocervical stimulation-evoked increases in neurotransmitter release in the nucleus of the solitary tract were found to be dependent on the coordinated transmission of information via the pelvic, hypogastric and vagal nerves (Guevara-Guzmán et al., 2001). Integration of signaling from more than one genitosensory nerve in response to mating could also be necessary for the induction of a CPP for mating.

In closing, the current experiment shows that the pelvic nerve is not essential for the reinforcing effects of mating whereas it is important for the specific patterns of behavior exhibited during paced mating. Future experiments will explore the role of alternate signaling pathways from the reproductive tract in the reinforcing effects of mating in female rats.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by HD050726 to Ann S. Clark. We thank Eilish Boisvert, Ragavan Narayanan, Kimberly Quill and Kersti Spjut for invaluable technical assistance. We are especially grateful to Dr. Tiffany Cunningham Donaldson for advice on the pelvic nerve transection and Dr. Robert N. Leaton for comments on the manuscript. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Mary S. Erskine for her work that inspired the present study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/bne.

References

- Beach FA. Sexual attractivity, proceptivity, and receptivity in female mammals. Hormones and Behavior. 1976;7:105–138. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(76)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkley KJ. The role of various peripheral afferent fibers in pain sensation produced by distension of the vaginal canal in rats. Pain Suppl. 1990;5:S403. [Google Scholar]

- Berkley KJ, Robbins A, Sato Y. Functional differences between afferent fibers in the hypogastric and pelvic nerves innervating female reproductive organs in the rat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;69:533–544. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.2.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein JD, Erskine MS. Feminine sexual behavior: cellular integration of hormonal and afferent information in the rodent forebrain. In: Pfaff DW, editor. Hormones, Brain and Behavior. Academic Press; New York: 2002. pp. 139–214. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RR, De Feo VJ. Role of the pelvic nerve vs. the abdominal sympathetic nerves in the reproductive function of the female rat. Endocrinology. 1965;77:1014–1022. doi: 10.1210/endo-77-6-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadha HK, Hubscher CH. Convergence of nociceptive information in the forebrain of female rats: Reproductive organ response variations with stage of estrus. Experimental Neurology. 2008;210:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopersmith C, Candurra C, Erskine MS. Effects of paced mating and intromissive stimulation on feminine sexual behavior and estrus termination in the cycling rat. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1996;110:176–186. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.110.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coria-Avila GA, Ouimet AJ, Pacheco P, Manzo J, Pfaus JG. Olfactory conditioned partner preference in the female rat. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119:716–725. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coria-Avila GA, Solomon CE, Vargas EB, Lemme I, Ryan R, Menard S, Gavrila A, Pfaus JG. Neurochemical basis of conditioned partner preference in the female rat: I. Disruption by naloxone. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;122:385–395. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueva-Rolon R, Sansone G, Bianca R, Gomez LE, Beyer C, Whipple B, Komisaruk BR. Vagotomy blocks responses to vaginocervical stimulation after genitospinal neurectomy in rats. Physiology and Behavior. 1996;60:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham ST, Steinman JL, Whipple B, Mayer AD, Komisaruk BR. Differential roles of hypogastric and pelvic nerves in the analgesic and motoric effects of vaginocervical stimulation in rats. Brain Research. 1991;559:337–343. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90021-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva N, Johnson OL, Berkley KJ. Bladder inflammation and hypogastric neurectomy influence uterine motility in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;313:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Salazar E, Camacho FJ, Paredes RG. Perinatal inhibition of aromatization enhances the reward value of sex. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;122:855–890. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery DE, Whitney JF. Effects of vagino-cervical stimulation upon sociosexual behaviors in female rats. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1985;43:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(85)91367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine MS. Solicitation behavior in the estrous female rat: a review. Hormones and Behavior. 1989;23:473–502. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(89)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine MS. Pelvic and pudendal nerves influence the display of paced mating behavior in response to estrogen and progesterone in the female rat. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1992;106:690–697. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.4.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine MS, Kornberg E, Cherry JA. Paced copulation in rats: effects of intromission frequency and duration on luteal activation and estrus length. Physiology and Behavior. 1989;45:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Bayon LE, Pursnani NK, Purdy RH. The neurosteroids, progesterone and 3alpha,5alpha-THP, enhance sexual motivation, receptivity, and proceptivity in female rats. Brain Research. 1998;808:72–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans S, Erskine MS. Effects of neonatal testosterone treatment on pacing behaviors and development of a conditioned place preference. Hormones and Behavior. 2003;44:354–364. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Horsman SP, Paredes RG. Dopamine antagonists do not block conditioned place preference induced by paced mating behavior in female rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118:356–364. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Horsman SP, Agmo A, Paredes RG. Infusions of naloxone into the medial preoptic area, ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, and amygdala block conditioned place preference induced by paced mating behavior. Hormones and Behavior. 2008;54:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Guzmán R, Buzo E, Larrazolo A, de la Riva C, Da Costa AP, Kendrick KM. Vaginocervical stimulation-induced release of classical neurotransmitters and nitric oxide in the nucleus of the solitary tract varies as a function of the oestrus cycle. Brain Research. 2001;898:303–313. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy DF, Debold JF. Effects of mounts without intromission upon the behavior of female rats during the onset of estrogen-induced heat. Physiology and Behavior. 1971;7:643–645. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH. Estradiol-associated variation in responses of rostral medullary neurons to somatovisceral stimulation. Experimental Neurology. 2006;200:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins WJ, Becker JB. Female rats develop conditioned place preferences for sex at their preferred interval. Hormones and Behavior. 2003;43:503–507. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WA. Female rats’ self-paced responding for artificial sexual stimulation. Behavioral Biology. 1977;21:401–411. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlert JG, Olexa N. The role of vaginal stimulation for the acquisition of conditioned place preference in female Syrian hamsters. Physiology and Behavior. 2005;84:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollar EJ. Reproduction in the female rat after pelvic nerve neurectomy. Anatomical Record. 1953;115:641–658. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komisaruk BR, Bianca R, Sansone G, Gomez LE, Cueva-Rolon R, Beyer C, Whipple B. Brain-mediated responses to vaginocervical stimulation in spinal cord-transected rats: role of the vagus nerves. Brain Research. 1996;708:128–134. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodder J, Zeilmaker GH. Role of pelvic nerves in the postcopulatory abbreviation of behavioral estrus in female rats. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1976;90:925–929. doi: 10.1037/h0077278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madlafousek J, Hlinak Z. Sexual behavior of the female laboratory rat: inventory, patterning and measurement. Behaviour. 1977;63:129–174. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez I, Paredes RG. Only self-paced mating is rewarding in rats of both sexes. Hormones and Behavior. 2001;40:510–517. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna KE. The neurophysiology of female sexual function. World Journal of Urology. 2002;20:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s00345-002-0270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerts SH, Clark AS. Female rats exhibit a conditioned place preference for nonpaced mating. Hormones and Behavior. 2007;51:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerts SH, Clark AS. Artificial vaginocervical stimulation induces a conditioned place preference in female rats. Hormones and Behavior. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.09.003. (in press) doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel RL, Joppa MA. Conditioned place preference in female hamsters following aggressive or sexual encounters. Physiology and Behavior. 1994;56:1115–1118. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hanlon JK, Meisel RL, Sachs BD. Estradiol maintains castrated male rats’ sexual reflexes in copula, but not ex copula. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1981;32:269–273. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(81)90645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco P, Martinez-Gomez M, Whipple B, Beyer C, Komisaruk BR. Somato-motor components of the pelvic and pudendal nerves of the female rat. Brain Research. 1989;490:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parada M, Tecamachaltzi-Silvaran MB, Chamas L, Coria-Avila GA, Pfaus JG. Clitoral stimulation induces conditioned place preference in the rat. Presented at the 12th Annual Meeting of the Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology; Groningen, The Netherlands. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes RG, Alonso A. Sexual behavior regulated (paced) by the female induces conditioned place preference. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1997;111:123–128. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes RG, Vazquez B. What do female rats like about sex? Paced mating. Behavioral Brain Research. 1999;105:117–127. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JT, Nuttall RL. Self-paced sexual behavior in the female rat. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1961;54:310–313. doi: 10.1037/h0040740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters LC, Kristal MB, Komisaruk BR. Sensory innervation of the external and internal genitalia of the female rat. Brain Research. 1987;408:199–204. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff DW, Lewis C. Film analyses of lordosis in female rats. Hormones and Behavior. 1974;5:317–335. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(74)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff DW, Agmo A. Reproductive motivation. In: Pashler H, Gallistel R, editors. Stevens’ handbook of experimental psychology, Learning, Motivation, and Emotion. Vol. 3. Wiley; New York: 2002. pp. 709–736. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaus JG, Manitt C, Coopersmith CB. Effects of pelvic, pudendal, or hypogastric nerve cuts on Fos induction in the rat brain following vaginocervical stimulation. Physiology and Behavior. 2006;89:627–636. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaus JG, Smith WJ, Byrne N, Stephens G. Appetitive and consumatory sexual behaviors of female rats in bilevel chambers. Hormones and Behavior. 2000;37:96–107. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DW, Erskine MS. c-Fos proto-oncogene activity induced by mating in the preoptic area, hypothalamus and amygdala in the female rat: role of afferent input via the pelvic nerve. Brain Research. 1993;621:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90294-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Hotta H, Nakayama H, Suzuki H. Sympathetic and parasympathetic regulation of the uterine blood flow and contraction in the rat. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1996;59:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(96)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JL, Bradshaw HB, Wood E, Berkley KJ. Effects of hypogastric neurectomy on escape responses to uterine distension in the rat. Pain Suppl. 1999;6:S13–S20. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toner JP, Adler NT. Influence of mating and vaginocervical stimulation on rat uterine activity. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1986;78:239–249. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0780239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker QD, Nelson CJ, Smith D, Kuhn CM. Vaginal lavage attenuates cocaine-stimulated activity and establishes place preference in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;73:743–752. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger SR, Baum MJ, Erskine MS. Mating-induced FOS-like immunoreactivity in the rat forebrain: a sex comparison and a dimorphic effect of pelvic nerve transection. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1993;5:557–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1993.tb00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]