Abstract

Background

Participation rates in cardiac rehabilitation following myocardial infarction (MI) remain low. Studies investigating the predictive value of psychosocial variables are sparse and often qualitative. We aimed to examine the demographic, clinical, and psychosocial predictors of participation in cardiac rehabilitation after MI in the community.

Methods

Olmsted County, Minnesota residents hospitalized with MI between June 2004 and May 2006 were prospectively recruited, and a 46-item questionnaire was administered prior to hospital dismissal. Associations between variables and cardiac rehabilitation participation were examined using logistic regression.

Results

Among 179 survey respondents (mean age 64.8 years, 65.9% male), 115 (64.2%) attended cardiac rehabilitation. The median (25th–75th percentile) number of sessions attended within 90 days of MI was 13 (5–20). Clinical characteristics associated with rehabilitation participation included younger age (odds ratio [OR] 0.95 per 1-year increase), male sex (OR 1.93), lack of diabetes (OR 2.50), ST elevation MI (OR 2.63), receipt of reperfusion therapy (OR 7.96), in-hospital cardiologist provider (OR 18.82), no prior MI (OR 4.17), no prior cardiac rehabilitation attendance (OR 3.85), and referral to rehabilitation in the hospital (OR 12.16). Psychosocial predictors of participation included placing a high importance on rehabilitation (OR 2.35), feeling that rehabilitation was necessary (OR 10.11), better perceived health prior to MI (excellent vs. poor OR 7.33), the ability to drive (OR 6.25), and post-secondary education (OR 3.32).

Conclusions

Several clinical and psychosocial factors are associated with decreased participation in cardiac rehabilitation programs after MI in the community. As many are modifiable, addressing them may improve participation and outcomes.

Introduction

Participation in cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction (MI) has been shown to improve survival, decrease the risk of recurrent MI, and improve exercise capacity1–5. In addition to the physical benefits of cardiac rehabilitation, participants have also been shown to experience psychosocial benefits including improved self-reported physical function5, less depression and anxiety6, and an improved sense of control over their disease7. These benefits have been found among both sexes and all ages8–11. Despite these benefits, cardiac rehabilitation participation rates are low in the United States, ranging from 14–55% after MI2, 12, with even lower participation by women and the elderly2, 11–15.

Many potential barriers to participation in cardiac rehabilitation have been proposed including lack of physician recommendation8, 16, lack of insurance16, and lower education15. Predictors of participation include revascularization14, 17, left ventricular dysfunction18 and regular physical activity prior to MI17. Psychosocial barriers have also been identified including depression8, 19, social deprivation and lower socioeconomic status17, 19, dependent spouse at home8, 20, lack of transportation20–23, lack of motivation16, 18, 20, 21, reduced self-efficacy 13, 24, 25, and perception that rehabilitation is inconvenient18, 23, 24 or unnecessary20, 21. However, many of these studies do not reflect contemporary practice, were narrative or provided information from focus group discussions or free-form interviews. Additionally, many were conducted among women only without a male group for comparison, or among rehabilitation participants without a non-participant group for comparison. Furthermore, few prospective studies exist to examine potential barriers to participation in rehabilitation. Consequently, predictive information is limited to factors that are routinely recorded in the medical record.

This prospective study was conducted to examine demographic, social, and psychosocial barriers to participation in and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation among a contemporary community cohort of persons presenting with acute MI.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Recruitment

We conducted a prospective study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, which has an estimated 2006 population of 137,521, 90% of whom are Caucasian. All Olmsted County residents with suspected acute MI and hospitalized at Mayo Clinic hospitals from June 18, 2004 to May 10, 2006 were identified using a two-step process. First, patients with elevated cardiac biomarkers were identified through the electronic medical record. The hospital charts of these patients were then reviewed by an investigator (BJW), or a trained study coordinator. Prior to hospital dismissal, English-speaking adults with a clinician-suspected diagnosis of acute MI or clinical history or electrocardiographic changes consistent with acute MI were asked to participate in the study by an investigator (BJW) or a study coordinator and research authorization and consent forms were signed. Persons were excluded if they had a physical impairment such as debilitating stroke, or medical condition that would limit their ability to fill out the survey instrument or participate in cardiac rehabilitation. Diagnosis of MI was subsequently confirmed using standard review of dismissal diagnoses following hospital discharge on patients who agreed to participate. Patients consenting to the study, but subsequently found not to have a clinical diagnosis of MI or did not complete the survey, were excluded from analysis.

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, and was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study; all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents.

Survey Instrument

All subjects agreeing to participate and providing consent were asked to complete a 46-item questionnaire prior to hospital dismissal for the index MI. Sixteen of these items consisted of the Health Self-Determinism Index (HSDI)26, a validated instrument used to measure health motivation. Each item on the HSDI was scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Total scores range from 16 to 80, with lower scores indicating extrinsic motivation for health behaviors and higher scores indicating intrinsic motivation. Another 13 of the survey items consisted of a modified version of the Cardiac Self-efficacy Questionnaire (CSE)27, a validated measure of a person’s judgment of their own capabilities as related to controlling their heart disease. Each item on the CSE was scored on a 4-point Likert scale, with lower scores indicating less confidence in ability to control one’s heart disease. The remaining items evaluated self-assessment of health status, importance of cardiac rehabilitation to the patient, motivating factors, education, living situation, transportation availability, insurance, and fears and concerns about rehabilitation such as cost, time commitment, and safety.

Patient Baseline Characteristics

Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure >140mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure >90mm Hg. Diabetes, hyperlipidemia, depression, family history of coronary artery disease (CAD), and smoking status (‘current’ or ‘former/never’) were defined according to diagnoses documented in the medical record. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the height and weight at the time of MI. Patients were classified as either being cared for by a cardiologist as the primary physician while in the hospital or another type of provider. ST segment elevation MI was defined using the Minnesota Code28. Reperfusion therapy was defined as percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, or receipt of thrombolytic therapy.

Clinical Endpoints

A single cardiac rehabilitation program exists in Olmsted County, and serves all residents. Outcome measures included cardiac rehabilitation participation, defined as appearance at the first outpatient visit to an organized cardiac rehabilitation program and adherence, defined as the total number of sessions attended in the three months following the first visit. Outcome data were obtained through passive surveillance of the electronic medical record as well as hospital billing records.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics are reported as frequency (%) for categorical variables or mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables. Differences in baseline characteristics and survey results by cardiac rehabilitation attendance were examined using χ2 for categorical variables and two sample t tests for continuous variables. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation attendance were determined using logistic regression analysis. Sex and age-specific interactions were tested. Multivariable analysis was performed by including all variables which were significantly associated with cardiac rehabilitation attendance in the model at once, and proceeding stepwise by backwards elimination until all remaining variables were significantly associated with cardiac rehabilitation attendance. Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (Cary, NC). A p value of <0.05 was used as the level of significance for all analyses.

Results

Patient Population

Among 363 patients approached, 279 patients consented to participate in the study (76.9%), and 245 of these met diagnostic criteria for MI present making them eligible for inclusion. Among those individuals, 179 completed the survey (73.1%) and constitute the final study population. The 179 participants completing the study were younger than non-participants (184 approached who did not consent or complete the study, 64.8 vs. 69.9 years, respectively, p<0.001) and more frequently male (65.9% vs. 55.7%, respectively, p=0.047).

Overall, 135 (74.6%) patients in the final study population had a non-ST segment elevation MI and 127 (71.0%) received reperfusion therapy for their MI. A large proportion of patients had comorbidities including diabetes (23.5%), hypertension (66.5%), hyperlipidemia (69.3%), and depression (20.1%). Approximately one-fifth (20.1%) were current smokers and the average BMI was 29.9 (SD 7.0 kg/m2).

Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation and Adherence

Among 179 study participants, 132 (73.7%) were referred to cardiac rehabilitation, and 115 (64.2%) participated. The mean number of cardiac rehabilitation sessions attended within 90 days of MI among participants was 13.5 (SD 8.2). The median number of sessions attended was 13, while 25% of patients attended 20 or more sessions, and 25% of patients attended 5 or fewer sessions. The number of sessions attended did not differ by sex (p=0.60) or age (p=0.19).

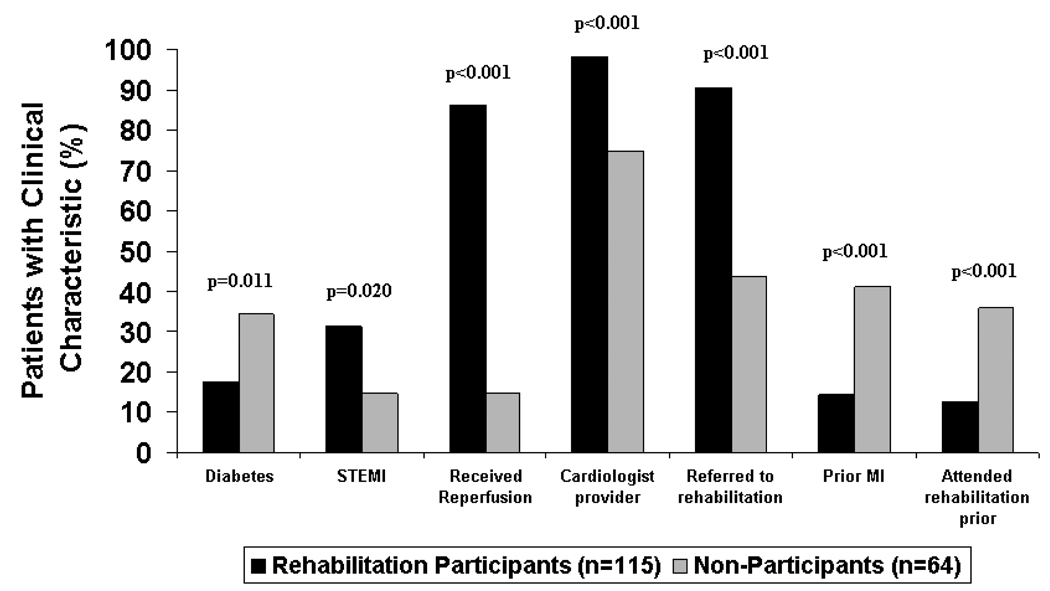

Several patient clinical characteristics were associated with cardiac rehabilitation participation (Figure 1, Table I). Cardiac rehabilitation participants were younger than non-participants (mean age 62.0 vs. 71.1 years, respectively, p<0.001) and more frequently male (71.3% vs. 56.3%, respectively, p=0.043). Diabetics were less likely to participate in rehabilitation. An ST elevation MI, receipt of reperfusion therapy in the hospital, in-hospital care by a cardiologist, and being referred to cardiac rehabilitation in the hospital were associated with increased participation. Patients with a prior MI and those who attended cardiac rehabilitation previously were less likely to participate. There were no differences between rehabilitation participants and non-participants in the frequency of hypertension (64.3% vs. 70.3%, respectively, p=0.418), hyperlipidemia (67.8% vs. 71.9%, p=0.574), depression (18.3% vs. 23.4%, p=0.409), and current smoking (21.7% vs. 17.2%, p=0.468). BMI was similar among rehabilitation participants and non-participants (mean 29.7 vs. 30.1, respectively, p=0.713).

Figure 1. Clinical Characteristics of Cardiac Rehabilitation Participants and Non-Participants.

Caption: Selected patient clinical characteristics by cardiac rehabilitation participation status are shown. STEMI= ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; MI= myocardial infarction

Table I.

Univariate Predictors of Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation

| Predictor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Age (per year increase) | 0.95 | 0.93, 0.98 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1.93 | 1.02, 3.66 | 0.043 |

| Diabetes | 0.40 | 0.20, 0.81 | 0.011 |

| MI Characteristics | |||

| ST elevation MI | 2.63 | 1.17, 5.92 | 0.020 |

| Received reperfusion therapy | 7.96 | 3.86, 16.39 | <0.001 |

| Cardiologist as primary provider in hospital | 18.82 | 4.17, 85.02 | <0.001 |

| Referred to cardiac rehabilitation in hospital | 12.16 | 5.50, 26.89 | <0.001 |

| Prior MI | 0.24 | 0.12, 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Attended cardiac rehabilitation previously | 0.26 | 0.12, 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Survey Results | |||

| High importance of rehabilitation | 2.35 | 1.20, 4.60 | 0.013 |

| Felt they needed rehabilitation | 10.11 | 4.75, 21.53 | <0.001 |

| Health prior to MI | <0.001 | ||

| Poor | 1.0 (referent) | -- | |

| Fair | 2.20 | 0.66, 7.39 | |

| Good | 5.57 | 1.66, 18.77 | |

| Very good | 8.14 | 2.29, 28.90 | |

| Excellent | 7.33 | 1.38, 38.88 | |

| Can’t drive | 0.16 | 0.06, 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Post high school education | 3.32 | 1.73, 6.34 | <0.001 |

MI= myocardial infarction

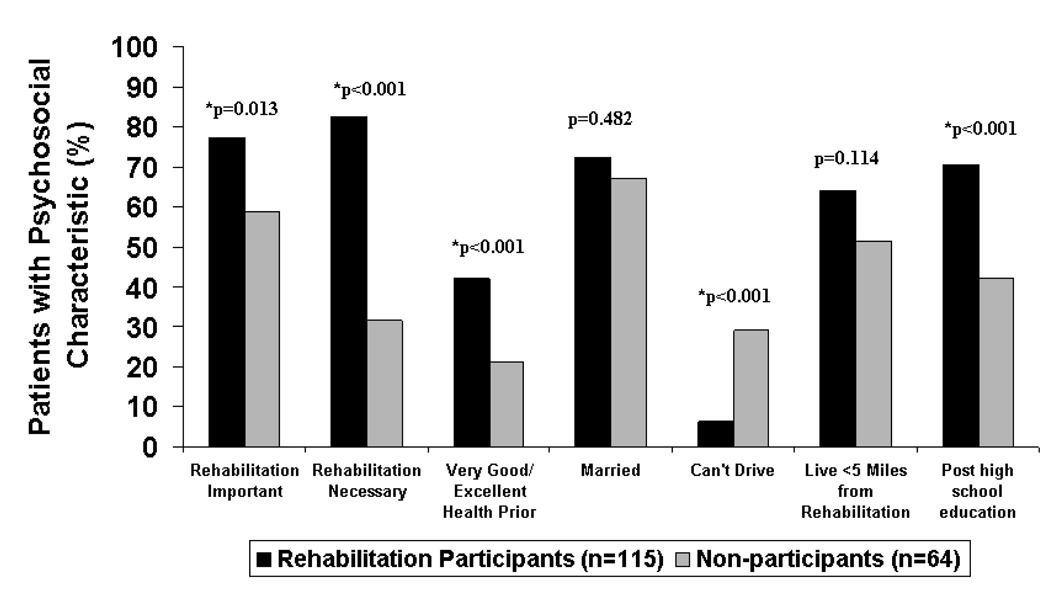

Several psychosocial factors were associated with cardiac rehabilitation participation (Figure 2, Table I). Recognition of the importance or necessity of cardiac rehabilitation, better perceived health prior to MI, the ability to drive, and a post-high school education were associated with increased likelihood of attending cardiac rehabilitation. Marital status and distance from a rehabilitation facility were not associated with differences in cardiac rehabilitation participation. There was no difference in health self-determinism by cardiac rehabilitation attendance (HDSI mean score 47.0 in those who attended vs. 47.3 in those who did not attend rehabilitation, p=0.742), or self-efficacy (CSE mean score 34.6 in those who attended vs. 32.8 in those who did not attend rehabilitation, p=0.338). Very few patients in this sample had no insurance (n=8), and cardiac rehabilitation participation rates were similar for those with Medicare (52.0%), Medicaid (53.3%), and only slightly higher for those with private insurance (68.9%).

Figure 2. Psychosocial Characteristics of Cardiac Rehabilitation Participants and Non-Participants.

Caption: Patient-reported psychosocial characteristics by cardiac rehabilitation participation status are shown.

Given the observed differences in cardiac rehabilitation participation by age and sex, age and sex-specific interactions were explored. In females, diabetes status had no impact on cardiac rehabilitation participation (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.36–3.29), while in males diabetes was associated with decreased participation (OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.09–0.56, p value for diabetes*sex=0.030). In males, higher BMI was associated with a trend toward decreased participation (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90–1.01 per 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI), while in females higher BMI was associated with a trend toward increased participation (1.05, 0.98–1.13 per 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI, p value for BMI*sex=0.028), though overall there was no association between BMI and rehabilitation participation (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.95–1.04 per 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI, p=0.713). There were no other significant interactions in cardiac rehabilitation participation by sex or age, indicating that the predictors of cardiac rehabilitation are similar among males and females, and younger and older individuals. It should be noted that a large number of interactions were explored, thus the significant interactions observed could have occurred by chance.

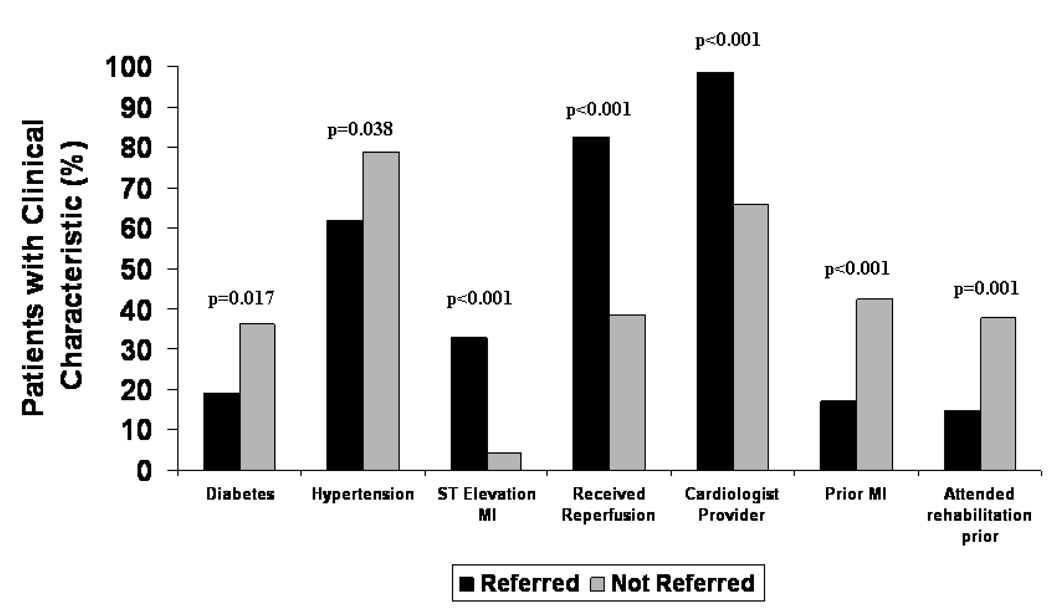

When all factors significantly associated with cardiac rehabilitation participation on univariate analysis were entered jointly into a model, while using stepwise backward elimination, four factors emerged as independent predictors of cardiac rehabilitation participation (Table II). The c statistic for the reduced model was 0.898, indicating that these 4 factors combined provided excellent prediction of cardiac rehabilitation attendance. Importantly, being referred to cardiac rehabilitation while in the hospital, which is an ACC/AHA performance measure29, was an important determinant of participation. Patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation were younger (mean 63.0 vs. 70.2 years, p=0.002) and more frequently male (72.7% vs. 46.8%, p=0.001) than those who were not referred. Additional differences in baseline characteristics between patients who were referred and not referred to cardiac rehabilitation are shown in Figure 3.

Table II.

Independent Predictors of Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation*

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per year increase) | 0.96 | 0.92–0.99 | 0.010 |

| Received reperfusion | 7.62 | 2.51–23.13 | <0.001 |

| Referred to rehabilitation while in the hospital | 6.14 | 2.12–17.74 | <0.001 |

| Felt they needed rehabilitation | 13.30 | 4.73–37.41 | <0.001 |

Factors associated with cardiac rehabilitation participation shown in Table I were entered into the logistic regression model, and independent predictors were determined using stepwise backward elimination C statistic= 0.898

Figure 3. Clinical Characteristics of Patients Referred and Not Referred to Cardiac Rehabilitation.

Caption: Differences in patient characteristics according to whether they received an in-hospital referral to cardiac rehabilitation are shown.

Additional Survey Results

When asked about the anticipated components of cardiac rehabilitation programs, the majority of patients reported they would receive information on diet (79.9%), heart disease (81.0%), risk factors (78.2%), related diseases (67.0%), and stress management (74.3%). Approximately 60% of patients reported they anticipated receiving physical therapy, reassurance regarding symptoms, and medication information. Just 72.2% of current smokers expected to receive help to quit smoking. Overall, 16.8% of patients did not know any of the components of cardiac rehabilitation. The majority of patients (63.7%) had some concerns regarding attending cardiac rehabilitation. The most common concerns cited included the associated costs and lack of insurance coverage (27.9%), perceived inconvenience (20.1%), lacking sufficient time to attend (14.0%), and a lack of transportation (14.0%). Overall, concerns were expressed more commonly among those who did not attend rehabilitation (78.1%) than those who attended (55.7%). Factors cited as most likely to increase a patient’s desire to attend cardiac rehabilitation included supportive staff (75.0%), provision of information regarding heart disease (73.5%), knowing it was paid for by insurance (75.5%), close monitoring while at rehabilitation (70.3%), and the ability to customize the program to their own needs (75.5%). While the majority of patients overall felt that separation of activities by sex would not influence their decision to attend (71.3%), women more frequently reported this would increase their desire to attend than men (39.6% vs. 17.3%, respectively). Most patients noted that separation of activities by age (62.6%) would not influence their decision to attend. While most patients felt that group activities would have no impact on their decision to attend (60.6%), many patients noted a decreased desire to attend for this reason (23.2%).

Discussion

Among this contemporary community cohort of MI survivors, 64% attended cardiac rehabilitation, though 25% attended 5 or fewer sessions in the 90 days following infarction. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation participation included younger age, male sex, lack of diabetes, ST elevation MI, receipt of reperfusion therapy, having a cardiologist as primary provider in the hospital, lack of prior MI, no prior cardiac rehabilitation attendance, and receiving a referral to cardiac rehabilitation while in the hospital. Psychosocial predictors of cardiac rehabilitation participation include placing a high importance and feeling a need for rehabilitation, better perceived health prior to MI, the ability to drive, and higher education level.

Cardiac rehabilitation participation rates are suboptimal in the United States12. Among this cohort, the rates of cardiac rehabilitation participation observed are similar to those reported previously in this community2, but higher than other populations. Participation rates among Medicare beneficiaries are known to vary widely by state in the U.S., though the reasons for these geographic variations are unclear. The Midwest has the highest rates, and Minnesota has the 4th highest in the country at 42.7%, as much as 6-fold higher than some other states12. Herein, 64% of participants attended cardiac rehabilitation, which is markedly higher than the nationwide average, and substantially higher than Minnesota. Several factors may play a role in the increased participation observed in this community relative to others. First, 73.7% of participants were referred to rehabilitation while in the hospital compared with a 53% referral rate reported by large registries after MI30. The increased referral to cardiac rehabilitation likely plays a key role in improved participation. Second, the close association between the cardiac rehabilitation program and the Mayo Clinic hospitals may increase participation rates. For example, electronic referral to cardiac rehabilitation is available in the hospital at the time of MI. After receiving a referral, a representative from the cardiac rehabilitation program visits each patient in the hospital to answer questions and provide an appointment for the first rehabilitation session. The day before the scheduled appointment, potential participants receive a phone call reminder. However, though a large proportion of patients attended cardiac rehabilitation in this cohort compared with other populations, cardiac rehabilitation was substantially underutilized. Only one-quarter of patients attended 20 or more sessions in the 90 days following MI, while one-quarter attended 5 or fewer sessions, despite the fact that Medicare and most other insurance companies in the U.S. reimburse up to three sessions per week for 12 weeks (36 total) following MI31. These data demonstrate that although higher levels of participation can be obtained in a community setting, adherence and completion of an appropriate number of sessions may be more difficult to attain.

Despite relatively high cardiac rehabilitation participation rates observed herein, many patients demonstrated a lack of sufficient knowledge of the components of cardiac rehabilitation programs and expressed concerns about attending cardiac rehabilitation. Approximately 1 in 6 patients reported a lack of knowledge of the components of cardiac rehabilitation, while two-thirds had concerns such as cost or inconvenience regarding rehabilitation with higher rates of concern expressed among those who subsequently did not participate. Further patient education and addressing expressed and elicited concerns regarding cardiac rehabilitation during hospitalization at the time of referral is a performance measure and may increase subsequent participation29.

Examination of the predictors of participation in cardiac rehabilitation may aid in developing ways to improve participation by targeting selected patients at high risk of non-participation. Many of the predictors of decreased participation observed herein have been consistent with other studies including older age2, 12, 19, female sex2, 12, 19, lack of physician referral8, 16, not feeling that rehabilitation is necessary20, 21, an inability to drive20–23, and education level15. However, in contrast to prior studies we found no difference in cardiac rehabilitation participation by insurance status12, 16, or driving distance from a rehabilitation center12. Several additional factors associated with increased participation were identified including a lack of diabetes, having an ST elevation MI, being cared for by a cardiologist in the hospital, and lack of a prior MI or prior cardiac rehabilitation participation. Further, development of a multivariable model including 4 factors independently associated with cardiac rehabilitation participation extends the previous literature. This model demonstrates that knowledge of a patient’s age, whether they received reperfusion therapy for MI, whether they received referral to cardiac rehabilitation while in the hospital, and whether they felt that they needed rehabilitation does an excellent job of predicting cardiac rehabilitation participation, as measured by a c statistic of 0.90.

This study was primarily limited by a small sample size. However, the amount of patient-level and psychosocial data present allows an in-depth look at this population compared with other studies relying largely on administrative data. Second, study participants were younger and more frequently male than those who did not participate, and thus age and sex-related differences in the predictors of participation may have been underestimated. On the other hand, half of patients included were over the age of 65, and one-third were women, which represents a wider age and sex distribution than many prior studies. Further, the majority of participants had health insurance, and the results may not apply to populations where a large proportion of patients have no insurance, though large registries have shown that only 8.2% of patients eligible for cardiac rehabilitation are uninsured nationwide30, compared with 4.5% in the present study. Finally, this community population was primarily Caucasian, and the results observed may not apply to communities of differing racial and ethnic composition.

Improving participation rates in cardiac rehabilitation programs could substantially improve survival following MI. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have demonstrated a 13–27% reduction in total mortality in patients participating in a cardiac rehabilitation program3, 32. While several factors associated with cardiac rehabilitation participation are not modifiable, such as age, sex, and MI characteristics, many of the factors identified have the ability to be addressed to potentially increase rehabilitation participation rates. Most notably, referral to a cardiac rehabilitation program while in the hospital was associated with a 6-fold increase in participation, even after adjustment. This is particularly important as referral to cardiac rehabilitation after MI is a performance measure endorsed by both the ACC and AHA29. In addition, patients who were primarily cared for by a cardiologist in the hospital had much higher rates of cardiac rehabilitation participation, suggesting that in-hospital care by a cardiologist provider may result in higher participation rates. Further, as patient opinions about the importance of rehabilitation as well as their perceived health were predictors of participation, in-hospital education about the necessity of cardiac rehabilitation and its associated survival benefits for all patients may improve participation. Finally, as the inability to drive is associated with reduced participation rates, discussion with patients about anticipated transportation and discussion of potential solutions may be beneficial. In large part, the predictors of cardiac rehabilitation participation did not differ by age or sex, suggesting that similar barriers to participation exist in these underrepresented populations, and strategies to increase participation may be similarly applied.

Cardiac rehabilitation programs after MI are associated with significant health benefits, including improved survival, but participation in the U.S. remains suboptimal. Despite the proven benefits, many patients are not referred to cardiac rehabilitation programs following MI, which represents a potential target for improvement. By addressing key modifiable risk factors for non-participation through improved patient education regarding the benefits of cardiac rehabilitation and discussion of expectations and perceived barriers to attendance, participation in cardiac rehabilitation programs following MI and associated patient outcomes may dramatically improve.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards for Dr. Dunlay(T32 HL07111-31A1), as well as an NIH Grant for Dr. Roger (RO159205), and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant #R01-AR30582 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None related to subject matter for all authors. Dr. Hayes is on an advisory board for Medtronic. Other authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Boulay P, Prud'homme D. Health-care consumption and recurrent myocardial infarction after 1 year of conventional treatment versus short- and long-term cardiac rehabilitation. Prev Med. 2004;38(5):586–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witt BJ, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Killian JM, Meverden RA, Allison TG, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(5):988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jolliffe JA, Rees K, Taylor RS, Thompson D, Oldridge N, Ebrahim S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800. CD001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ades PA. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):892–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra001529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rejeski WJ, Foy CG, Brawley LR, Brubaker PH, Focht BC, Norris JL, 3rd, et al. Older adults in cardiac rehabilitation: a new strategy for enhancing physical function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(11):1705–1713. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oldridge N, Streiner D, Hoffmann R, Guyatt G. Profile of mood states and cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(6):900–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchard CM, Rodgers WM, Courneya KS, Daub B, Black B. Self-efficacy and mood in cardiac rehabilitation: should gender be considered? Behav Med. 2002;27(4):149–160. doi: 10.1080/08964280209596040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ades PA, Waldmann ML, Polk DM, Coflesky JT. Referral patterns and exercise response in the rehabilitation of female coronary patients aged greater than or equal to 62 years. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69(17):1422–1425. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90894-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forman DE, Farquhar W. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs for elderly cardiac patients. Clin Geriatr Med. 2000;16(3):619–629. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams MA, Ades PA, Hamm LF, Keteyian SJ, LaFontaine TP, Roitman JL, et al. Clinical evidence for a health benefit from cardiac rehabilitation: an update. Am Heart J. 2006;152(5):835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suaya JA, Stason WB, Ades PA, Normand SL, Shepard DS. Cardiac Rehabilitation and Survival in Older Coronary Patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Normand SL, Ades PA, Prottas J, Stason WB. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1653–1662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper A, Lloyd G, Weinman J, Jackson G. Why patients do not attend cardiac rehabilitation: role of intentions and illness beliefs. Heart. 1999;82(2):234–236. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber K, Stommel M, Kroll J, Holmes-Rovner M, McIntosh B. Cardiac rehabilitation for community-based patients with myocardial infarction: factors predicting discharge recommendation and participation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evenson KR, Rosamond WD, Luepker RV. Predictors of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation utilization: the Minnesota Heart Surgery Registry. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1998;18(3):192–198. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199805000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evenson KR, Fleury J. Barriers to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation participation and adherence. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2000;20(4):241–246. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane D, Carroll D, Ring C, Beevers DG, Lip GY. Predictors of attendance at cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51(3):497–501. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackburn GG, Foody JM, Sprecher DL, Park E, Apperson-Hansen C, Pashkow FJ. Cardiac rehabilitation participation patterns in a large, tertiary care center: evidence for selection bias. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2000;20(3):189–195. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper AF, Jackson G, Weinman J, Horne R. Factors associated with cardiac rehabilitation attendance: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(5):541–552. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr524oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher R, McKinley S, Dracup K. Predictors of women's attendance at cardiac rehabilitation programs. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;18(3):121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2003.02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farley RL, Wade TD, Birchmore L. Factors influencing attendance at cardiac rehabilitation among coronary heart disease patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2(3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Missik E. Women and cardiac rehabilitation: accessibility issues and policy recommendations. Rehabil Nurs. 2001;26(4):141–147. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2001.tb01937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieberman L, Meana M, Stewart D. Cardiac rehabilitation: gender differences in factors influencing participation. J Womens Health. 1998;7(6):717–723. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grace SL, Abbey SE, Shnek ZM, Irvine J, Franche RL, Stewart DE. Cardiac rehabilitation I: review of psychosocial factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(3):121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Missik E. Personal perceptions and women's participation in cardiac rehabilitation. Rehabil Nurs. 1999;24(4):158–165. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1999.tb02164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox CL. The Health Self-Determinism Index. Nurs Res. 1985;34(3):177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan MD, LaCroix AZ, Russo J, Katon WJ. Self-efficacy and self-reported functional status in coronary heart disease: a six-month prospective study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(4):473–478. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199807000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blackburn H. Classification of the electrocardiogram for population studies: Minnesota Code. J Electrocardiol. 1969;2(3):305–310. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(69)80120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas RJ, King M, Lui K, Oldridge N, Pina IL, Spertus J, et al. AACVPR/ACC/AHA 2007 performance measures on cardiac rehabilitation for referral to and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention services endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Sports Medicine, American Physical Therapy Association, Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation, European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, Inter-American Heart Foundation, National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(14):1400–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown TM, Hernandez AF, Bittner V, Cannon CP, Ellrodt G, Liang L, et al. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation referral in coronary artery disease patients: findings from the American Heart Association's Get With The Guidelines Program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(6):515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenger NK. Current status of cardiac rehabilitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(17):1619–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, Jolliffe J, Noorani H, Rees K, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2004;116(10):682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]