Abstract

We have reported some type II restriction-modification (RM) gene complexes on plasmids resist displacement by an incompatible plasmid through postsegregational host killing. Such selfish behavior may have contributed to the spread and maintenance of RM systems. Here we analyze the role of regulatory genes (C), often found linked to RM gene complexes, in their interaction with the host and the other RM gene complexes. We identified the C gene of EcoRV as a positive regulator of restriction. A C mutation eliminated postsegregational killing by EcoRV. The C system has been proposed to allow establishment of RM systems in new hosts by delaying the appearance of restriction activity. Consistent with this proposal, bacteria preexpressing ecoRVC were transformed at a reduced efficiency by plasmids carrying the EcoRV RM gene complex. Cells carrying the BamHI RM gene complex were transformed at a reduced efficiency by a plasmid carrying a PvuII RM gene complex, which shares the same C specificity. The reduction most likely was caused by chromosome cleavage at unmodified PvuII sites by prematurely expressed PvuII restriction enzyme. Therefore, association of the C genes of the same specificity with RM gene complexes of different sequence specificities can confer on a resident RM gene complex the capacity to abort establishment of a second, incoming RM gene complex. This phenomenon, termed “apoptotic mutual exclusion,” is reminiscent of suicidal defense against virus infection programmed by other selfish elements. pvuIIC and bamHIC genes define one incompatibility group of exclusion whereas ecoRVC gene defines another.

Keywords: programmed cell death, epigenetics, intragenomic conflicts, phage exclusion, plasmid

A type II restriction-modification (RM) gene complex, such as EcoRI, codes for an endonuclease that cleaves DNA at a specific sequence and a cognate modification enzyme that methylates the same sequence to protect it from restriction. A bacterial cell can contain multiple RM gene complexes either on the chromosome or on plasmids. It is widely held that bacteria have evolved these RM systems and maintain them to protect themselves from invasion by foreign DNA such as bacteriophage DNA and plasmids. However, there are several issues that cannot be explained readily by this cellular defense hypothesis (1).

We found that a plasmid carrying an RM gene complex could not be displaced readily by a second, incompatible plasmid, even when the incoming plasmid was resistant to restriction by the resident RM system (2, 3). Similarly, we found it very difficult to replace an RM gene complex placed on the chromosome by a homologous stretch of DNA through homologous recombination (Y.N. and I.K., unpublished results).

This apparent stability of RM gene complexes turned out to result from death of cells that have lost them (2, 3). Our experimental analysis suggested the following course of events. After a cell has lost its RM gene complex, its descendants will contain fewer and fewer molecules of the modification enzyme. Eventually, their capacity to modify the many sites needed to protect the newly replicated chromosomes from the remaining pool of restriction enzyme may become inadequate. Chromosomal DNA will then be cleaved at the unmodified sites, and the cells will be killed (refs. 2–4; N. Handa, A. Ichige, K. Kusano, and I.K., unpublished results). This result is similar to the postsegregational host killing mechanisms for maintenance of several plasmids (5). These RM gene complexes were able to increase the apparent stability of a plasmid that carry them by postsegregational host killing in a pure culture (2, 4, 6). (Although we are aware that host killing in pure cultures is rather artificial, it nonetheless provides a convenient experimental system for analysis.)

We suggest that the host killing mediated by an RM complex gives it (and any DNA linked to it) an advantage in its competition with other genetic elements. After host killing, copies of the RM gene complex would survive in the neighboring clonal cells, enjoying resources that would be otherwise unavailable if the cells carrying the competitor genetic element had not died. The phenomenon we observe is also similar to the altruistic suicide (apoptosis in mammalian terminology) of cells infected with viruses, which serves to counteract secondary infection of neighboring cells. In prokaryotes, this type of cell deaths is called phage exclusion and is programmed by resident genetic elements such as prophages, plasmids, or prophage-like polymorphic units (7).

The conflict between the host and the RM gene system may have contributed to the spread and maintenance of the RM gene complexes. In this way, they resemble proviruses and other genetic elements that are often called selfish genes or selfish genetic elements (8). In general, two homologous alleles in diploid eukaryotic cells segregate in a one-to-one ratio at meiosis. This Mendelian law of segregation is violated by some genes in a process called “meiotic drive.” These selfish genes are preferentially transmitted over the other, nonself alleles (8). In particular, the action of maternal-effect selfish genes, which cause postfertilization killing (9), appears to be quite similar to the action of the RM gene complexes, i.e., the loss of the selfish gene leads to killing of the progeny by the residual gene product. Thus, the RM gene complexes warrant the term “selfish genes” in the genetic sense of the term.

Properties of the RM systems have been explained by the cellular defense hypothesis. However, some features of their organization and behavior can be explained by the selfish gene concept (1, 2, 4).

(i) A gene that behaves selfishly by killing the host would benefit from moving from one genome to another. Thus, the movement of the RM gene complexes, suggested by various lines of evidence (10–14), makes sense under the selfish gene hypothesis. The ability to be mobile as a unit requires the R and M genes to be linked tightly.

(ii) Although the cognate restriction enzyme and modification enzyme recognize the same sequence, they are physically separated. The linkage of their genes will allow simultaneous loss of R and M genes, which is a condition for postsegregational killing. The physical separation of their gene products, on the other hand, will allow execution of host killing by the restriction enzyme.

(iii) The host killing by an RM system will not work when the second RM system in the cell shares the same sequence specificity. Methylation of the recognition site by the modification enzyme of one RM system will protect it from cleavage by the restriction enzyme of the other RM system. Thus, two RM systems of the same sequence specificity cannot be stabilized simultaneously. These predictions were confirmed in experiments (4). Because this type of incompatibility implies exclusive competition for specific sequences on genomes by RM systems, it would result in the specialization of each of these selfish gene units in only one of many diverse sequences. This result would explain why RM gene products display, individually, high sequence specificity but, collectively, wide diversity in their recognition sites. The apparently independent evolution of numerous restriction enzymes, as inferred from the virtual absence of sequence homology among them (15), can be explained, at least in part, by “adaptive radiation,” i.e., specialization to specific recognition sequences by the above diversifying selection, at very early periods.

(iv) The attack of RM systems on invading DNA, such as bacteriophage and plasmid DNA, is consistent with the selfish gene hypothesis (as well as the cellular defense hypothesis). The RM system within a bacterial cell will benefit from such an attack. In this case, there is no conflict between the RM system and the host.

(v) The various features of bacterial homologous recombination may be understood as being the result of an ambivalent strategy of the host toward RM gene complexes. If the restriction enzymes attack invading DNAs without a specific 8-mer sequence called χ, the host RecBCD enzyme will degrade them completely (16). If the restriction enzymes attack the bacterial chromosome marked by χ, the RecBCD/RecA machinery will repair the chromosome through homologous recombination (ref. 17; N. Handa, A. Ichige, K. Kusano, and I.K., unpublished data).

The organization of RM gene complexes is often similar to that of prophages, which are another sort of self-perpetuating genetic elements (10). An example is a family of genes, called C, whose member is tightly linked to some RM gene complexes and regulates expression of these RM genes (18–21). They carry a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif and display weak homology with the cI regulatory gene of bacteriophage λ. Some heterologous pairs of C genes are interchangeable (22).

In this work, we present evidence for the roles of C genes in the following social interactions of RM systems: (i) their resistance to displacement through postsegregational host killing; (ii) their establishment in a new host; and (iii) their capacity to exclude another RM system of the same C specificity but of different restriction/modification specificity through apparent cell suicide. These findings are in accord with the selfish gene hypothesis for the spread and maintenance of RM gene complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Escherichia coli strains JC8679 (recB21 recC22 rac sbcA23), and DH5 (recA1 endA1 hsdR17) have been described (23). DH5 was used for plasmid construction, propagation of plasmids, and measurement of restriction activity. ER1562 (= mcrA1272∷Tn10 hsdR2 mcrB1, an MM294 derivative; ref 24) was provided by New England Biolabs. E. coli strains were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium or SOB medium (25). When appropriate, antibiotics were supplemented at the following concentrations: 50 mg/liter ampicillin (Ap) (with 200 mg/liter methicillin), 25 mg/liter chloramphenicol (Cm), or 50 mg/liter Kanamycin (Km).

Bacillus subtilis strain RM125 from M. Itaya (Mitsubishi Kagaku Institute of Life Science) (26) was used for propagation of pBamHIRM22 (described below). The B. subtilis strain was grown in LB with 20 mg/l tetracycline (Tc).

Bacteriophages.

LIK351 (= λ cI-71) was from Frank Stahl (University of Oregon).

Plasmids.

Plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Plasmids

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Prototype plasmid | Drug resistance | Source and/or reference* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pYNEC106 | ecoRVRMC | Unknown | none | This work, (27) |

| pYNEC107 | ecoRVRMC | pBR322 | Ap | This work, (27) |

| pYNEC111 | ecoRVRMC | pBR322 | Ap | This work |

| pYNEC112 | ecoRVRMC | pUC19 | Ap | This work |

| pYNEC113 | ecoRVRMC | pBR322 | Ap | This work |

| pYNEC114 | ecoRVRMC | pHSG415 | Ap, Cm | This work |

| pYNEC115 | ecoRVR−MC | pUC19 | Ap | This work |

| pYNEC116 | ecoRVRMC− | pUC19 | Ap | This work |

| pYNEC117 | ecoRVR−MC | pBR322 | Ap | This work |

| pYNEC118 | ecoRVRMC− | pBR322 | Ap | This work |

| pYNEC119 | ecoRVR−MC | pHSG415 | Ap, Cm | This work |

| pYNEC120 | ecoRVRMC− | pHSG415 | Ap, Cm | This work |

| pYNEC126 | ecoRVC | plK153 | Cm | This work |

| pYNEC130 | ecoRVC− | plK153 | Cm | This work |

| pPvuRM3.4 | pvullRMC | pBR322 | Ap | R. M. Blumenthal (Medical College of Ohio) (28) |

| pYNEC300 | pvullRMC | pUC19 | Ap | This work, (28) |

| pYNEC302 | pvullR−MC | pUC19 | Ap | This work, (19) |

| pYNEC303 | pvullRMC− | pUC19 | Ap | This work, (18) |

| pYNEC304 | pvullR−MC− | pUC19 | Ap | This work, (19) |

| pYNEC311 | pvullC | plK153 | Cm | This work, (19) |

| pYNEC323 | pvullRMC | plK153 | Cm | This work, (28) |

| pYNEC324 | pvullR−MC | plK153 | Cm | This work, (19) |

| pYNEC325 | pvullRMC− | plK153 | Cm | This work, (18) |

| pBamHIRM22 | bamHlRMC | pTB53 | Tc, Km | B. Kawakami (Toyobo) (29) |

| pYNEC401 | bamHlC | plK158 | Cm | This work |

| pYNEC403 | bamHlRMC | pUC19 | Ap | This work |

| pYNEC404 | bamHlRMC− | pUC19 | Ap | This work |

| pBR322 | Ap, Tc | Laboratory stock | ||

| pHSG415 | Temperature-sensitive for replication | Ap, Km, Cm | J. Kato (University of Tokyo) (30) | |

| pKC31 | λ phage replication origin | Bacteriophage λ | Km | (31) |

| plK153 | pACYC184 | Cm | K. Kusano (our laboratory) | |

| plK158 | pACYC184 | Cm | K. Kusano (our laboratory) | |

| pYNEC332 | No BamHI site | pKC31 | Km | This work, (31) |

| pYNEC333 | No BamHI site | plK153 | Cm | This work |

Reference for DNA inserted to generate the listed plasmid.

The NdeI digests of pYNEC106, which was isolated from J62 (pGL74) [provided by M. Watahiki (Nippon Gene); ref. 27] and which carries the EcoRV RM gene complex, was further cut with BglII and PvuII. The resulting BglII/PvuII fragment was inserted between the BamHI site and PvuII site of pBR322 (pYNEC107). pYNEC107 was cut with NdeI, treated with Klenow fragment ,and ligated with a BamHI linker (5′-CCGGATCCGG) (pYNEC111). The BamHI/HindIII fragment of pYNEC111 was inserted between the BamHI site and HindIII site of pUC19 (pYNEC112). This BamHI/HindIII fragment also was inserted into pBR322 and pHSG415 to generate pYNEC113 and pYNEC114, respectively.

The ecoRVR disruptant was made by cleaving pYNEC112 at a PstI site present within the ecoRVR gene, followed by treatment with T4 DNA polymerase (which has exonuclease activity) and self-ligation (pYNEC115). This process results in a 4-bp deletion of the ecoRVR gene. The ecoRVC disruptant was generated by replacing the 6 bp between the HincII sites with an 8-bp long ClaI linker (5′-CATCGATG) (pYNEC116). BamHI/HindIII fragments of pYNEC115 and pYNEC116 were introduced between the BamHI site and HindIII site of pBR322 and pHSG415. Plasmids carrying ecoRVC were generated by inserting the fragment between the PstI site and EcoT22I site of pYNEC112 or pYNEC116 (ecoRVC disruption mutant) into the PstI site of pIK153. pIK153 is a derivative of pACYC184, which has deletion of the largest HaeII fragment and has replacement of the shorter HindIII/EcoRV fragment by a HindIII/PvuII fragment (with multiple cloning sites) from pUC119. It was constructed and provided by Kohji Kusano (our laboratory).

pYNEC300 was derived from pUC19 and possesses the EcoRI/BamHI fragment from pPvuRM3.4 (provided by R. M. Blumenthal, ref. 28). The plasmid was altered at the EcoT14I site (= StyI site) and/or ClaI site to generate pvuIIR and/or pvuIIC disruption mutants as described (18, 19). pYNEC311 possesses a XhoI/SpeI fragment containing both the pvuIIR and pvuIIC mutations from pYNEC304 (19). pYNEC401 is a pIK158 derivative with the Sau3AI/BalI fragment containing the bamHIC gene from pBamHIRM22 (provided by B. Kawakami; ref. 29) inserted between its BamHI site and SmaI site. At the BalI site in the bamHIR gene of pYNEC403, an XhoI linker (5′-CCTCGAGG) was inserted (pYNEC404).

Assay of Transformation Efficiency.

Plasmids were purified by banding in cesium chloride-ethidium bromide. They were used to transform E. coli strains by electroporation with a Gene Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad) as described (32). The number of transformants was normalized by the number of transformants of an internal control plasmid as described in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Identification of a C Gene in the EcoRV RM Gene Complex.

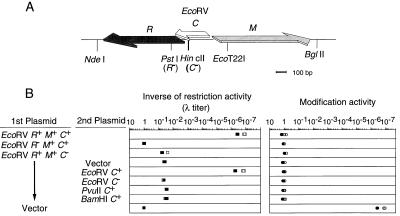

We first tried to demonstrate the presence of a C gene in the EcoRV RM gene complex. Others (18, 22) have reported that the predicted amino acid sequence of a small ORF within the EcoRV RM gene complex (Fig. 1A) shows strong similarity to the pvuIIC gene product and that this ORF fails to complement for other known C proteins. However, the functional significance of this putative ecoRVC gene has never been determined in the EcoRV system itself.

Figure 1.

(A) Genetic and restriction map of EcoRV RMC genes (modified from ref. 27). (B) Effects of the ecoRVC mutation on the restriction and modification activities. The ratio of the number of λ plaques on the test strain to that on DH5 (pBR322) is shown (Left). The λ phage grown in each strain was assayed on DH5 (pYNEC113) and DH5 (pBR322); the ratio of the number of plaques on these two strains is shown (Right). Measurements were carried out in duplicate in two separate experiments.

We introduced a frameshift mutation within this ORF but outside of the R and M genes (see Materials and Methods). This ecoRVC frameshift mutation reduced EcoRV restriction activity ≈105-fold; in comparison, the reduction was ≈107-fold when the restriction gene itself was mutated (Fig. 1B). The restriction activity in an ecoRVC mutant was restored when a compatible plasmid carrying an intact copy of ecoRVC was also present (Fig. 1B). Restoration was not observed when the second plasmid contained the frameshift mutation in ecoRVC. Fragments that expressed the homologous genes pvuIIC (18, 19) or bamHIC (20, 22) did not restore EcoRV restriction activity (Fig. 1B). In contrast to restriction, the ability to modify bacteriophage λ appeared to be unchanged in the ecoRVC mutant. It seems clear that ecoRVC specifies an active positive regulator of the EcoRV RM gene complex.

The C Mutation Eliminates the Apparent Stabilization Effect of EcoRV RM System Through Postsegregational Host Killing.

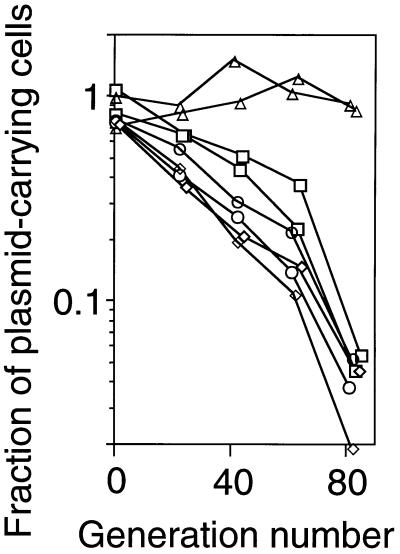

We previously reported that a plasmid is apparently stabilized in E. coli strains when it carries the PaeR7I or EcoRI RM gene complex (2, 4). Although plasmid stabilization under pure culture conditions is artificial, this experimental system provided a simple way to analyze the behavior of RM systems. We measured the stability of a series of plasmids carrying EcoRV RM gene complex or its mutant derivatives. The fraction of host cells that retained the plasmid was measured after prolonged growth in liquid medium in the absence of antibiotic selection. As we expected, the plasmid carrying the intact EcoRV RMC gene complex was apparently much more stable than the vector plasmid, pBR322 (Fig. 2). Introduction of a mutation in the C gene completely eliminated this stabilizing effect, as did a mutation in the restriction gene (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Apparent stability of plasmids with the EcoRV RM gene complex and its mutant versions. During repeated batch culture (106-fold dilution and overnight incubation) in the absence of any selective antibiotics, aliquots were assayed on LB agar plates with and without Ap. The ratio of these colony counts was taken as the fraction of cells carrying the plasmid. The generation number was estimated from the colony counts on LB agar. □, pBR322; ▵, pYNEC113 (R+ M+ C+); ○, pYNEC117 (R- M+ C+); and ◊, pYNEC118 (R+ M+ C−).

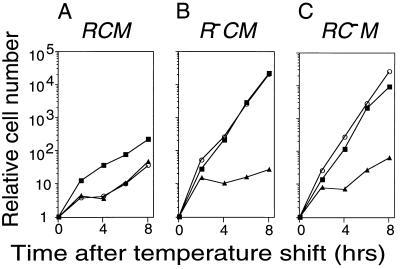

The apparent plasmid stabilization effect of EcoRV RM system likely is to be the result of postsegregational killing as indicated by previous results with the PaeR7 and EcoRI systems (2, 4). The C mutation should affect such killing because in C mutants little restriction activity is produced (18–21; Fig. 1B). To prove this, we examined for cell death after inducing the loss of an RM plasmid carrying a mutation in either the restriction gene (R) or regulatory gene (C). The EcoRV RM gene complex was placed on a temperature-sensitive replicon whose replication can be blocked by a temperature shift-up. After a lag period, the shift-up in temperature was found to stop the increase in the number of viable cells with plasmids (Fig. 3). In the case of the R+ M+ C+ plasmid, the viable cell count and plasmid-carrying viable cell count were found to stop increasing at about the same time after the shift (Fig. 3A). This indicates that postsegregational killing had occurred in these cells. On the other hand, the temperature shift had no detectable effect on the viability of cells carrying the R- M+ C+ plasmid or the R+ M+ C− plasmid (Figs. 3 B and C). Therefore, C gene function is required for plasmid stabilization.

Figure 3.

Postsegregational host cell killing following induced loss of the EcoRV RM gene complex. The replication of repts plasmids carrying EcoRV RM gene complex was blocked by a temperature shift. The bacterial cells [JC8679 (pYNEC114), JC8679 (pYNEC119), and JC8679 (pYNEC120)] were incubated at 30°C in LB broth with Ap until the OD660 of the culture reached 0.3. Antibiotics were then removed, and the temperature was shifted to 42°C. The culture was diluted when the OD660 reached 0.3 (≈5 × 108 cell/ml). The number of total cells (▪) was counted under a microscope. The number of viable cells (○) and plasmid-carrying cells (▴) were measured by counting colonies on LB agar plates and LB agar plates containing Ap, respectively.

Resident C Genes Prevent Establishment of Homologous RM Systems.

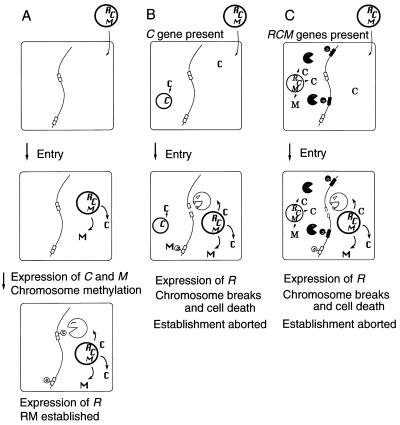

One possible role of the C gene might be to facilitate the establishment of an RM system in a new host bacterial cell (18). When an RM gene complex enters a host cell whose DNA is unmodified, it is essential for establishment that the cell DNA be methylated before restriction endonuclease expression begins. Otherwise, the DNA of the host cell would be digested. Efficient establishment would be achieved if the requirement for a critical concentration of C protein delayed synthesis of the restriction enzyme (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Hypotheses for the establishment and apoptotic mutual exclusion of RM gene complexes containing a C gene. (A) A plasmid carrying an RM gene complex enters a cell. M and C genes are expressed first. After the modification enzyme has modified almost all the chromosomal sites, the accumulation of C protein induces the restriction enzyme. (B) Entry of a plasmid carrying an RM gene complex into a cell carrying C gene from the same RM gene complex. The resident C protein induces the expression of the incoming R gene, whose product cleaves the unmodified chromosomal sites and kills the cell. (C) Entry of a plasmid carrying an RM gene complex into a cell harboring another RM gene complex with a different sequence specificity but with the same C protein specificity. The resident C protein induces the incoming R gene, whose product cleaves the unmodified chromosomal sites and kills the cell.

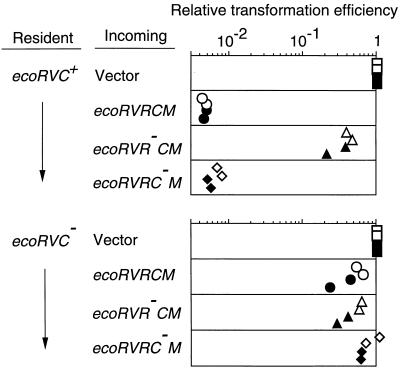

If this hypothesis is correct, an already established ecoRVC gene would be expected to promote the expression of the r gene of an invading RM gene complex and lead to cell killing through chromosome breakage (Fig. 4B). To test this prediction, cells containing an intact C gene or its mutant form were transformed by a plasmid carrying the EcoRV RM gene complex. As expected, the transformation efficiency of the plasmid with EcoRV R+ M+ C+ was much lower than that of the vector (Fig. 5 Top, 1st and 2nd rows). The huge size of the decrease in the transformation efficiency was dependent both on the incoming restriction gene (Fig. 5 Top, 3rd row) and on the resident C gene (Fig. 5 Bottom). We obtained similar results with the PvuII RM system (see Fig. 7), confirming another study (33). These results support the idea that the C-mediated differential expression of RM genes prevents the premature restriction of chromosome during RM gene establishment.

Figure 5.

Effect of a resident ecoRVC on the establishment of an incoming EcoRV RM system. Cells carrying pYNEC126 (ecoRVC+) or pYNEC130 (ecoRVC−) were transformed with 150 ng of pYNEC113 (R+ M+ C+), pYNEC117 (R− M+ C+), pYNEC118 (R+ M+ C−), or pBR322 (vector). Each DNA solution contained 100 ng of pKC31 (KmR) as an internal control of the transformation efficiency. For each assay, the number of ApR transformants was divided by the number of KmR transformants. The relative transformation efficiencies are the above ratios further divided by the ratio for pBR322. The measurements were carried out in duplicate in two separate experiments.

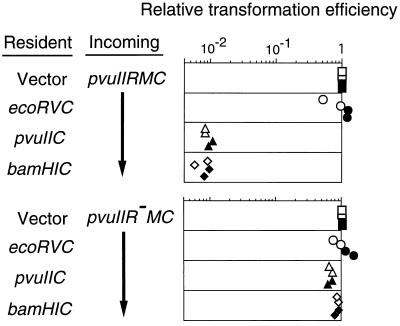

Figure 7.

Effect of various C genes on the establishment of an incoming PvuII RM system. Cells carrying pYNEC126 (ecoRVC+), pYNEC130 (ecoRVC−), pYNEC311 (pvuIIC+), pYNEC401 (bamHIC+), or pIK153 (vector) were transformed with 150 ng of pYNEC300 (PvuII R+ M+ C+) or pYNEC302 (PvuII R− M+ C+). Each DNA solution contained 100 ng of pKC31 (KmR) as an internal control of the transformation efficiency. For each assay, the number of ApR transformants was divided by the number of KmR transformants. The relative transformation efficiencies are the above ratios further divided by the ratio for pIK153. The measurements were carried out in duplicate in two separate experiments.

A Resident RM System Prevents Establishment of an RM System Having the Same C Specificity but Different Sequence Specificity.

The C genes of BamHI and PvuII are interchangeable with respect to the expression of the R gene (22). We expected that such cross complementation would cause apoptotic mutual exclusion between RM systems in the following manner. The C protein of the resident RM system would promote premature expression of the restriction enzyme gene of the incoming RM system, leading to chromosome cleavage at sites unmodified by the incoming RM system, and consequent cell killing (Fig. 4C).

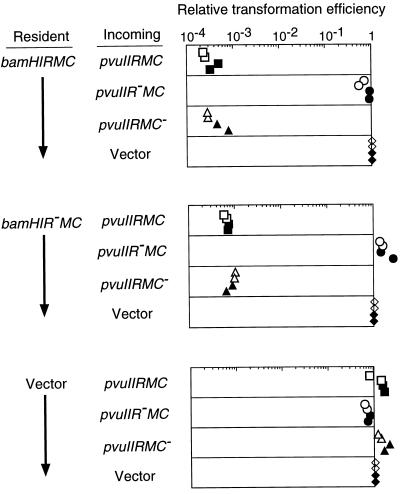

This prediction was confirmed by the results shown in Fig. 6. The presence of the BamHI RM gene complex in the recipient cell reduced the transformation efficiency of a plasmid carrying the PvuII RM gene complex more than 1,000-fold compared with the vector alone (Fig. 6 Top, 1st and 4th rows). This decrease in transformation efficiency was dependent on the restriction gene of the incoming PvuII RM system (Fig. 6 Top, 2nd row) but not on the restriction gene of the resident BamHI RM system (Fig. 6 Middle). Such a difference in the transformation efficiency was not observed when the BamHI RM gene complex was absent from the cell (Fig. 6 Bottom).

Figure 6.

Effect of a resident BamHI RM system on the establishment of an incoming PvuII RM system. Cells carrying pYNEC403 (BamHI R+ M+ C+), pYNEC404 (BamHI R− M+ C+) or pBR322 were transformed with 90 ng of pYNEC323 (PvuII R+ M+ C+), pYNEC324 (PvuII R− M+ C+), pYNEC325 (PvuII R+M+ C−), or pYNEC333 (vector). Each DNA solution contained 60 ng of pYNEC332 (KmR) as an internal control of the transformation efficiency. For each assay, the number of ApR transformants was divided by the number of KmR transformants. The relative transformation efficiencies are the above ratios further divided by the ratio for pYNEC333. The measurements were carried out in duplicate in two separate experiments.

A similar decrease in transformation efficiency also was observed when the recipient cell contained only the bamHIC gene (Fig. 7 Top, 4th row). This was again dependent on the incoming restriction gene (Fig. 7 Bottom, 4th row).

Incompatibility Groups Defined by C Specificity.

ecoRVC failed to abort the establishment of the PvuII system (Fig. 7 Top, 2nd row). This result is in agreement with the inability of the ecoRVC gene to complement the PvuII R+ M+ C− mutant for restriction (ref. 22; Fig. 1B). The efficiency of plaque formation (plating efficiency) of λ was 9 × 10−5 on a PvuII R+ M+ C+ strain but was 0.59 on a PvuII R+ M+ C− strain. Reintroducing the pvuIIC gene into cells carrying PvuII R+ M+ C− decreased this level to 7.1 × 10−4, but in the presence of the ecoRVC gene, the PvuII restriction remained nearly unchanged at 0.51. Thus, we conclude that the PvuII and BamHI RM systems form one incompatibility group defined by their C genes, whereas the EcoRV RM system belongs to another C incompatibility group.

DISCUSSION

Maintenance of RM Gene Complexes.

The EcoRV RM system was able to apparently stabilize plasmids through postsegregational host killing as did the RM systems of PaeR7I and EcoRI (2, 4). The selection for maintenance in host cells through host killing appears to be a general property of type II RM systems (see also ref. 6). Their properties can be explained if they are regarded as selfish gene entities or genomic parasites, molecular parasites that attack DNA genome (see above).

A mutation in the ecoRVC gene was found to eliminate postsegregational host killing. Therefore, the C gene is necessary for the maintenance of parasitism by the EcoRV RM gene complex. We do not know yet whether the C gene plays this role only through positive regulation of R gene expression or whether there exist multiple pathways involving the C gene.

This role of the C gene appears similar to that of the transcription regulators of temperate bacteriophages, such as the λ cI transcription regulator. The cI gene product positively regulates its own transcription and this is essential for the maintenance of its lysogenic (parasitic) state. One possible advantage procured by the presence of a regulatory gene is that it can integrate information about environmental changes into its decision about whether or not to kill the host cell.

Establishment of RM Systems.

The abortion of establishment of the EcoRV and PvuII RM systems in cells containing a homologous C gene is in agreement with the previously proposed role of the C gene system in delaying restriction (18). The proposed sequence of expression of RMC genes—expression of M gene and C gene before that of R gene—is reminiscent of the orchestrated series of events that occur during bacteriophage infection, and especially during the establishment of lysogeny. RM systems without a C regulatory gene probably possess some alternative means of ensuring that M gene expression occurs prior to R gene expression (34–37).

Apoptotic Mutual Exclusion Between RM Systems.

The presence of one RM gene complex or its C gene in a host aborted establishment of an incoming RM gene complex of the same C specificity but of different sequence specificity. Therefore, the presence of C gene of the same specificity in RM gene complexes with different sequence specificities can result in the resident RM system interfering with the spread of the second RM system.

Our results suggest that the C gene of the resident RM system forces the incoming RM system to express its restriction enzyme prematurely, and thus killing the host through the cleavage of its, yet, unmodified recognition sites on the chromosome. This process is similar to the apoptotic or host killing strategy that an RM system shows in competitive exclusion with other genetic elements (such as an incompatible plasmid). Two RM systems recognizing different sequences are potentially in competition because postsegregational host killing by one RM gene complex will result in death of the copies of the other RM gene complex in the host. After the apparently altruistic suicide of the host “infected” with the competitor RM system, copies of the resident RM gene complex would be expected to survive in the neighboring clonal cells “uninfected” with the competitor RM system. Therefore, we would like to call this phenomenon “apoptotic mutual exclusion” between RM systems.

There are examples of genes active in both postsegregational killing and in phage exclusion (38). Methyl-specific restriction enzymes have been proposed to represent a cell suicide strategy against invasion by some RM gene complexes (1). As soon as an invading RM system starts methylating the host chromosome at some sites, these methyl-specific restriction enzymes will introduce breaks there and kill the invaded cells. These altruistic cell deaths would prevent spreading of some RM systems in the bacterial cell population.

A resident EcoRV RM gene complex, the C gene of which does not act on the PvuII RM system, did not cause cell killing after invasion by the PvuII RM system. It is likely that each C gene specificity defines an incompatibility group of exclusion. In this view, pvuIIC and bamHIC define one incompatibility group and ecoRVC defines another.

The apoptotic mutual exclusion will not work if the two RM systems recognize the same sequence (see Fig. 4). We previously demonstrated that each recognition sequence of the RM systems defines a separate incompatibility group (see above) (4). Therefore, there are two complementary incompatibility relationships among RM systems: one type of incompatibility is based on the specificity of the sequence recognition, and the other type is based on the specificity of a regulatory gene. The latter type of incompatibility works only if two RM systems do not show the first type of incompatibility.

Competition for recognition sequences may underlie the collective diversity and individual specificity of sequence recognition by RM systems (see above) (4). Likewise the diversity and the specificity of the C regulator may have been the result of mutual competition between RM systems.

Apoptotic mutual exclusion was identified using one specific combination of RM systems, but there are several reasons to believe that this may be a general phenomenon.

(i) There exist other C-homologues linked to RM gene complexes (18, 20, 21). These include MunI (39) and BglII (13). Also, small ORFs have been found linked to other RM gene complexes although they share little or no homology with C (e.g., Eco57I, HgiCI, and HgiCII) (39–41). Their sequences may have diverged rapidly during evolution as a result of the diversifying selective pressure discussed above.

(ii) Some RM gene complexes are associated with a putative regulatory gene but have lost it during the cloning process (41). It is possible that some of the previously cloned RM gene pairs were likewise separated from a regulatory gene.

(iii) All of the RM systems are expected to have some mechanism to delay restriction during establishment in a host as discussed above (18, 34–37). Such a regulatory machinery would allow evolution of mutual exclusion mediated by apoptosis if the machinery were associated with RMs of different sequence specificities.

In any case, experimental demonstration of the presence of apoptotic mutual exclusion in a given pair of RM systems should be quite straightforward.

In summary, C genes were found to play important roles in the maintenance, establishment, and mutual exclusion of RM systems. These roles are reminiscent of the strategies of temperate bacteriophages (42), which constitute another type of self-perpetuating genetic elements. The present results are in accord with our hypothesis that the selfish behavior of the RM systems, seemingly in conflict with the host bacteria, has contributed to their spread and maintenance in bacterial populations.

Acknowledgments

Kohji Kusano (our laboratory) provided several plasmids and helpful suggestions. We thank Bob Blumenthal, Masanori Watahiki, Bunsei Kawakami, Mitsuyasu Itaya, and New England BioLabs for generous gifts of biological materials. Bob Blumenthal and Michael Yarmolinsky provided helpful comments on manuscripts. This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Sports, Science and Culture of the Japanese government, Nagase Science Foundation, and Takeda Science Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Ap

ampicillin

- Km

kanamycin

- Cm

chloramphenicol

- Tc

tetracycline

- RM

restriction modification

- LB

Luria–Bertani medium

References

- 1.Kobayashi I. In: Epigenetic Mechanisms of Gene Regulation. Russo V, Martienssen R, Riggs A, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1996. pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naito T, Kusano K, Kobayashi I. Science. 1995;267:897–899. doi: 10.1126/science.7846533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naito, Y., Naito, T. & Kobayashi, I. (1998) Biol. Chem. 379, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kusano K, Naito T, Handa N, Kobayashi I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11095–11099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen R B, Gerdes K. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulakauskas S, Lubys A, Ehrlich S D. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3451–3453. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3451-3454.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder L. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:415–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurst D, Atlan A, Bengtsson B O. Q Rev Biol. 1996;71:317–364. doi: 10.1086/419442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beeman R W, Friesen K S, Denell R E. Science. 1992;256:89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1566060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson G G, Murray N E. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:585–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeltsch A, Pingoud A. J Mol Evol. 1996;42:91–96. doi: 10.1007/BF02198833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaišvila R, Vilkaitis G, Janulaitis A. Gene. 1995;157:81–84. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00793-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anton B P, Heiter D F, Benner J S, Hess E J, Greenough L, Moran L S, Slatko B E, Brooks J E. Gene. 1997;187:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00638-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brassard S, Paquet H, Roy P H. Gene. 1995;157:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00734-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeltsch A, Kröger M, Pingoud A. Gene. 1995;160:7–16. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simmon V F, Lederberg S. J Bacteriol. 1972;112:161–166. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.1.161-169.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi N K, Sakagami K, Kusano K, Yamamoto K, Yoshikura H, Kobayashi I. Genetics. 1997;146:9–26. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tao T, Bourne J C, Blumenthal R M. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1367–1375. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.4.1367-1375.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tao T, Blumenthal R M. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3395–3398. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3395-3398.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ives C L, Nathan P D, Brooks J E. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7194–7201. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7194-7201.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimšelienė R, Vaišvila R, Janulaitis A. Gene. 1995;157:217–219. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00794-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ives C L, Sohail A, Brooks J E. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6313–6315. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6313-6315.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi N, Kusano K, Yokochi T, Kitamura Y, Yoshikura H, Kobayashi I. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5176–5185. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5176-5185.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raleigh E A, Murray N E, Revel H, Blumenthal R M, Westaway D, Reith A D, Rigby P W, Elhai J, Hanahan D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1563–1575. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.4.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanahan D. In: DNA Cloning. Glover D M, editor. Vol. 1. Oxford: IRL; 1985. pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uozumi T, Hoshino T, Miwa K, Horinouchi S, Beppu T, Arima K. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;152:65–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00264941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bougueleret L, Schwarzstein M, Tsugita A, Zabeau M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:3659–3676. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.8.3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blumenthal R M, Gregory S A, Cooperider J S. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:501–509. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.501-509.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawakami B, Katsuragi N, Maekawa Y, Imanaka T. J Ferment Bioeng. 1990;70:211–214. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashimoto-Gotoh T, Franklin F C H, Nordheim A, Timmis K N. Gene. 1981;16:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wold M S, Mallory J B, Roberts J D, LeBowitz J H, McMacken R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6176–6180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi N, Kobayashi I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2790–2794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vijeseurier R M. Ph.D. thesis. Detroit, MI: Wayne State Univ.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedman S, Som S. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6293–6298. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6293-6298.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alvarez M A, Gomez A, Gomez P, Rodicio M R. Gene. 1995;157:231–232. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00862-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvarez M A, Chater K F, Rodicio M R. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:243–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karyagina A, Shilov I, Tashlitskii V, Khodoun M, Vasil’ev S, Lau P C K, Nikolskaya I. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.11.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pecota D C, Wood T K. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2044–2050. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2044-2050.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson G G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2539–2566. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.10.2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janulaitis A, Vaisvila R, Timinskas A, Klimasauskas S, Butkus V. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6051–6056. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.22.6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kröger M, Blum E, Deppe E, Düsterhöft A, Erdmann D, Kilz S, Meyer-Rogge S, Möstl D. Gene. 1995;157:43–47. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00779-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell A. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:193–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]