Abstract

Background and Aims

Knowledge of pollen dispersal patterns and variation of fecundity is essential to understanding plant evolutionary processes and to formulating strategies to conserve forest genetic resources. Nevertheless, the pollen dispersal pattern of dipterocarp, main canopy tree species in palaeo-tropical forest remains unclear, and flowering intensity variation in the field suggests heterogeneity of fecundity.

Methods

Pollen dispersal patterns and male fecundity variation of Shorea leprosula and Shorea parvifolia ssp. parvifolia on Peninsular Malaysian were investigated during two general flowering seasons (2001 and 2002), using a neighbourhood model modified by including terms accounting for variation in male fecundity among individual trees to express heterogeneity in flowering.

Key Results

The pollen dispersal patterns of the two dipterocarp species were affected by differences in conspecific tree flowering density, and reductions in conspecific tree flowering density led to an increased selfing rate. Active pollen dispersal and a larger number of effective paternal parents were observed for both species in the season of greater magnitude of general flowering (2002).

Conclusions

The magnitude of general flowering, male fecundity variation, and distance between pollen donors and mother trees should be taken into account when attempting to predict the effects of management practices on the self-fertilization and genetic structure of key tree species in tropical forest, and also the sustainability of possible management strategies, especially selective logging regimes.

Keywords: Dipterocarp, general flowering, male fecundity variation, microsatellite marker, paternity analysis, pollen dispersal, Shorea, tropical forest

INTRODUCTION

Identifying pollen dispersal patterns is important because they play key roles in determining the rates of successful outcrossing and shaping the genetic diversity and structuring of natural plant populations (e.g. Wright, 1946; Crawford, 1984; Ennos, 1994). Therefore, pollen dispersal patterns have profound implications for forest succession, evolutionary plant biology and conservation strategies. Most tropical tree species depend on insects for pollination (Bawa et al., 1985), and in species-rich tropical forests low population densities of conspecific adult trees have led biologists to predict that tropical trees are likely to be highly dependent on self-fertilization, and thus to have high inbreeding coefficients (e.g. Corner, 1954; Fedorov, 1966). However, control pollination studies and recent mating system studies with genetic markers have revealed that insect-pollination can yield unexpectedly high rates of outcrossing and long-distance pollen dispersal (e.g. Bawa, 1974; Murawski and Hamrick, 1991; Ward et al., 2005). In addition, a wide variety of pollination symbioses have evolved in tropical forests, which are likely to lead to differences in pollen dispersal patterns between plant species, especially as the population dynamics of pollinator species may show considerable spatial and temporal variation. Variability in other factors, notably conspecific flowering tree densities, flowering phenology and its synchronicity, may also lead to major between-species differences in pollen dispersal patterns, effective pollination distances and, possibly, degrees of genetic isolation.

Estimations of ecological parameters relative to reproductive success and gene flow in dense tropical forests have been hindered by difficulties in observing reproductive phenomena in high canopies. However, by modelling pollen dispersal and reproductive parameters it is possible to circumvent these problems, and thus: to quantify inter-population patterns of pollen and seed movements in a spatially explicit manner; to obtain insight into contemporary patterns of gene flow in a landscape context; and to consider various factors affecting reproductive success (Burczyk et al., 1996, 2002; Burczyk and Prat, 1997; Bacles et al., 2005). Many authors have also attempted to estimate the fecundities of individual males within populations directly using genetic information (e.g. Meagher, 1991; Devlin et al., 1992; Burczyk and Prat, 1997). In addition, the heterogeneity of male fecundity has been incorporated into models by including appropriate ecological and physiological variables in order to obtain more reasonable parameter estimates and to account for factors influencing male fecundity variation within populations (Burczyk et al., 2002; Oddou-Muratorio et al., 2005; Burczyk and Prat, 1997). Klein et al. (2008) estimated parameters for male reproduction fecundity of all potential pollen donors in the neighbourhood based on paternity assignments and detected wide variability in individual male fecundity. This approach should be very valuable especially in tropical forests because difficulty of accessibility to the tall canopy makes it difficult to conduct direct observation of mating processes.

Shorea leprosula and Shorea parvifolia ssp. parvifolia are ecologically and economically important members of the Dipterocarpaceae, the dominant timber family in south-east Asia. Generally, Shorea species produce small, hermaphroditic flowers and are pollinated by small insects, such as thrips and small beetles (Appanah and Chan, 1981; Momose et al., 1998; Sakai et al., 1999). Previous studies have examined aspects of pollen dispersal patterns, effective pollination and gene flow in various members of the Dipterocarpaceae. These studies have identified a hermaphrodite flower-adopted mixed-mating system (Murawski et al., 1994a; Lee et al., 2000) and have demonstrated tendencies for their selfing rates to increase with reductions in population density (Murawski et al., 1994b; Nagamitsu et al., 2001; Obayashi et al., 2002; Fukue et al., 2007). Direct estimates of Dipterocarpaceae pollen dispersal patterns have revealed that a high proportion of pollen originates from outside study plots and that pollen dispersal frequency rapidly declines with increasing distance from the pollen source (Konuma et al., 2000; Fukue et al., 2007; Naito et al., 2008). However, pollen dispersal curves and male fecundity variation in this important family have not been discussed in detail and remained to be elucidated. In particular, it was reported that a reduction of population density, such as by selective logging activity, increased selfing in Shorea species (Murawski et al., 1994b; Obayashi et al., 2002), and therefore estimates of these parameters will be valuable for developing effective conservation strategies and improving the sustainability of management practices in tropical forests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research plot, sampling strategy and DNA extraction

The Pasoh Forest Reserve (Pasoh FR) located at Negri, Sembilan State, in the centre of the southern Malaysian Peninsula (2°58′N, 102°18′E) is a designated conservation area of lowland dipterocarp forest (details are described in, for example, Manokaran and LaFrankie, 1990; Condit et al., 1996, 1999; He et al., 1997). A 40-ha (500 × 800 m) plot in the Reserve has been established since 1998 that is located at the edge of a 50-ha long-term demographic research plot and includes a 6-ha International Biological Plot (IBP), used for molecular ecological research (Konuma et al., 2000; Takeuchi et al., 2004; Naito et al., 2005, 2008). All trees of two important dipterocarp species, Shorea leprosula Miq. and Shorea parvifolia Dyer. ssp. parvifolia, in the 40-ha plot with a diameter at breast height (dbh) exceeding 30 cm were mapped (Figs 1 and 2). Inner bark or leaf samples of all mapped individuals of both species (n = 61 and 70, respectively) were collected. In 2001 and 2002, sporadic and mass general flowering events were observed in the Malaysian Peninsula (Numata et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2007). All individuals that flowered in the plot during the two events were carefully monitored by monthly direct observations from 4 September, 2001 to 14 February 2002 during the 2001 flowering event, and once every 2 weeks from 2 April, 2002 to the 26 September, 2002 during the 2002 flowering event. Seeds were collected from under the canopies of five and eight S. leprosula trees and four and five S. parvifolia trees (assumed to be the respective seeds' maternal trees), in 2001 and 2002, respectively. Part of the seeds in 2002 were collected under the canopy of mother trees and sown in a nursery at the Pasoh FR research station; therefore, DNA was extracted from the embryos or leaves of the germinated seedlings of 9–112 offspring per tree in each year (mean = 40·0, SD = 29·4; see Table 3 below). Genomic DNA was extracted from leaves, inner bark and embryo tissues using a method described by Murray and Thompson (1980). The extracted DNA was further purified using a High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche).

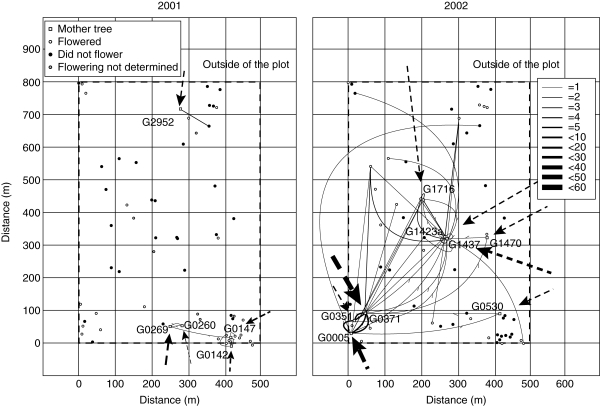

Fig. 1.

The distribution of adult trees (dbh > 30 cm), pollen dispersal routes and flowering events according to field observations in Shorea leprosula. Open squares represent the locations of the mother trees from which seeds were collected (shown with tree IDs); circles represent the locations where adult trees flowered, did not flower and flowering was not determined, as indicated. The lines and arrows show pollen routes within the plot and cryptic pollen dispersal, respectively (from the paternity analysis). The widths of the lines and arrows correspond to the number of pollen dispersal events detected, as indicated in the scale on the right-hand side of the figure.

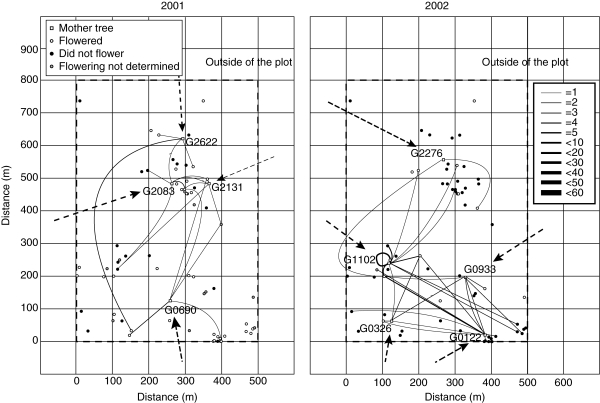

Fig. 2.

The distribution of adult trees (dbh > 30 cm), pollen dispersal routes, and flowering events according to field observations and pollen production estimates derived from the parameter α̂j in Shorea parvifolia. Open squares represent the locations of the mother trees from which seeds were collected (shown with tree IDs); circles represent the locations where adult trees flowered, did not flower and flowering was not determined, as indicated. The lines and arrows show pollen routes within the plot and cryptic pollen dispersal, respectively (from the paternity analysis). The widths of the lines and arrows correspond to the number of pollen dispersal events detected, as indicated in the scale on the right-hand side of the figure.

Table 3.

Number of offspring analysed in the parentage analysis, selfing and outcrossing rates, and rates of crossing mediated by pollen from outside the plot

| Maternal tree | Masting year | Number of offspring analysed* |

No. of paternal donors† | Rate of pollen dispersal from outside the plot |

Selfing rate estimated from paternity analysis |

Rate of allogamous offspring sired by paternal donor inside the plot | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed | Seedling | Total | Seed | Seedling | Total (mi) | Seed | Seedling | Total (si) | ai | |||

| S. leprosula | ||||||||||||

| G0142 | 2001 | 40 | – | 40 | 3 | 0·300 | – | 0·300 | 0·625 | – | 0·625 | 0·075 |

| G0147 | 2001 | 20 | – | 20 | 2 | 0·850 | – | 0·850 | 0·000 | – | 0·000 | 0·150 |

| G0260 | 2001 | 9 | – | 9 | 2 | 0·556 | – | 0·556 | 0·333 | – | 0·333 | 0·111 |

| G0269 | 2001 | 32 | – | 32 | 4 | 0·781 | – | 0·781 | 0·094 | – | 0·094 | 0·125 |

| G2952 | 2001 | 28 | – | 28 | 2 | 0·786 | – | 0·786 | 0·179 | – | 0·179 | 0·036 |

| Population estimate | 2001 | 129 | – | 129 | 3·000 | 0·628 | – | 0·628 | 0·279 | – | 0·279 | 0·093 |

| G0005 | 2002 | 62 | 38 | 100 | 7 | 0·452 | 0·632 | 0·520 | 0·194 | 0·026 | 0·130 | 0·350 |

| G0351 | 2002 | 5 | 18 | 23 | 1 | 0·200 | 0·778 | 0·652 | 0·000 | 0·000 | 0·000 | 0·348 |

| G0371 | 2002 | 64 | 48 | 112 | 10 | 0·484 | 0·563 | 0·518 | 0·219 | 0·250 | 0·232 | 0·250 |

| G0530 | 2002 | 11 | 27 | 38 | 2 | 0·455 | 0·259 | 0·316 | 0·545 | 0·667 | 0·632 | 0·053 |

| G1423a | 2002 | 15 | 31 | 46 | 9 | 0·467 | 0·613 | 0·565 | 0·200 | 0·097 | 0·130 | 0·304 |

| G1437 | 2002 | 15 | 48 | 63 | 12 | 0·467 | 0·563 | 0·540 | 0·267 | 0·125 | 0·159 | 0·302 |

| G1470 | 2002 | 5 | 18 | 23 | 2 | 0·800 | 0·722 | 0·739 | 0·200 | 0·222 | 0·217 | 0·043 |

| G1716 | 2002 | 39 | – | 39 | 3 | 0·179 | – | 0·179 | 0·744 | – | 0·744 | 0·077 |

| Population estimate | 2002 | 216 | 228 | 444 | 6·375 | 0·417 | 0·575 | 0·498 | 0·319 | 0·193 | 0·255 | 0·248 |

| Total or mean of S. leprosula | 345 | 228 | 573 | 5·077 | 0·496 | 0·575 | 0·527 | 0·304 | 0·193 | 0·260 | 0·213 | |

| S. parvifolia | ||||||||||||

| G0690 | 2001 | 35 | – | 35 | 6 | 0·229 | – | 0·229 | 0·629 | – | 0·629 | 0·143 |

| G2083 | 2001 | 37 | – | 37 | 5 | 0·486 | – | 0·486 | 0·378 | – | 0·378 | 0·135 |

| G2131 | 2001 | 11 | – | 11 | 6 | 0·273 | – | 0·273 | 0·091 | – | 0·091 | 0·636 |

| G2622 | 2001 | 23 | – | 23 | 5 | 0·217 | – | 0·217 | 0·609 | – | 0·609 | 0·174 |

| Population estimate | 2001 | 106 | – | 106 | 4·250 | 0·321 | – | 0·321 | 0·481 | – | 0·481 | 0·198 |

| G0122 | 2002 | 7 | 41 | 48 | 8 | 0·286 | 0·488 | 0·458 | 0·429 | 0·317 | 0·333 | 0·208 |

| G0326 | 2002 | 41 | 48 | 89 | 4 | 0·171 | 0·063 | 0·112 | 0·805 | 0·875 | 0·843 | 0·045 |

| G0933 | 2002 | – | 15 | 15 | 5 | – | 0·333 | 0·333 | – | 0·400 | 0·400 | 0·267 |

| G1102 | 2002 | 24 | 25 | 49 | 11 | 0·417 | 0·360 | 0·388 | 0·042 | 0·000 | 0·020 | 0·592 |

| G2276 | 2002 | 15 | – | 15 | 3 | 0·400 | – | 0·400 | 0·467 | – | 0·467 | 0·133 |

| Population estimate | 2002 | 87 | 129 | 216 | 5·000 | 0·287 | 0·287 | 0·287 | 0·506 | 0·473 | 0·509 | 0·204 |

| Total or mean of S. parvifolia | 193 | 129 | 322 | 4·667 | 0·306 | 0·287 | 0·298 | 0·492 | 0·473 | 0·495 | 0·207 | |

| Total or mean of all mother trees | 538 | 357 | 895 | 4·909 | 0·428 | 0·471 | 0·445 | 0·372 | 0·294 | 0·353 | 0·202 | |

*The numbers in the columns represent the mean values for the total number of samples analysed in the paternity analysis.

†The paternal donor was detected within the plot, but the paternal donors outside the plot were not identified.

Molecular analysis

All samples were genotyped at ten microsatellite loci, using primers developed by Ujino et al. (1998) and Lee et al. (2004). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications were carried out in total reaction volumes of 10 µL using a GeneAmp 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) instrument. The PCR mixture contained 0·2 µm of each primer, 0·2 mm of each dNTP, 20 mm Tris–HCl (pH 8·4), 50 mm KCl, 1·5 mm MgCl2, 0·25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and 0·5–3 ng of template DNA. The temperature programme was as follows: 3 min at 94 °C, then 30–35 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 50–57 °C and 45 s at 72 °C, followed by a 5-min extension step at 72 °C. Amplified PCR fragments were electrophoretically separated by using an ABI3100 genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems) with a calibrating internal size standard (GeneScan ROX 400HD). The genotype of each individual was determined from the resulting electrophoregrams by GENOTYPER ver. 3.7 software (Applied Biosystems).

Paternity assignment and mating system

Before assigning paternal parents, offspring genotypes that conflicted with the assumed maternal tree genotypes were excluded from the offspring genotype array. Such conflicts can arise because seed dispersal and canopy overlaps of individuals of the same species sometimes cause the misallocation of maternal parents when seeds are collected from under the canopy of presumed maternal trees. The numbers of excluded offspring were 67 (10 %) and 84 (17 %) for S. leprosula and S. parvifolia, respectively [not included in the number of offsprings analysed (see Table 3 below)]. After the exclusion of erroneous maternal offspring, the paternity of each offspring was determined by a combination of likelihood and simple exclusion procedures implemented in Cervus ver. 2.0 (Marshall et al., 1998). The likelihood ratios and their confidence levels (>95 %) were used for paternity assignment. However, if the significant paternal candidates identified from the likelihood procedure had more than two loci mismatches in the simple exclusion procedure, the paternal tree of the offspring was assumed to be located outside of the plot and the offspring was not assigned to any paternal candidates. The electrophorograms were double checked to confirm mismatch between the offspring and paternal candidate in these cases to minimize genotyping error. Selfing rate was estimated by dividing the number of self-fertilized offspring by the total number of analysed offspring per mother tree, supported by the paternity analysis. In this procedure, the selfing rate was presumably over-estimated if erroneous assignment of selfing had occurred, which was mainly caused by cryptic pollen dispersal.

Estimation of pollen dispersal parameters

Pollen dispersal parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method described below, which is similar to that used in several previous studies (Burczyk et al., 1996; Burczyk and Koralewski, 2005; Klein et al., 2008). It is necessary to take account of the accuracy of parentage assignments when the resolution of parentage analyses is low, i.e. when the genotypes of offspring frequently match more than one candidate father in a plot, or there is a significant possibility that the true fathers of the offspring are located outside the plot. Burczyk et al. (1996, 2002) proposed the use of ML methods for considering the effects of parentage accuracy and cryptic gene flow. However, if parentage accuracy is very high, simpler likelihood functions can be validly applied, as in the present study. Therefore, the probability of paternal contribution for each mother tree was estimated using a simpler model, rather than the neighbourhood model, to estimate the genetic transition probabilities between the offspring and unknown local fathers or a local pollen donor.

The pollen sources of offspring from a particular mother tree, i, were categorized as ni (the number of allogamous offspring whose paternal donor was detected in the plot),  (the number of offspring whose paternal donor was not detected in the plot, i.e. the number of offspring resulting from pollen originating from outside of the plot) and nij(s) [the number of offspring of the ith mother tree whose assigned paternal donor (jth) was the same adult tree as the mother tree (synonym of selfing, ignoring possible cryptic pollen dispersal)]. The model used to describe pollen movement within the plot was ni. The categorical relationships for number and rate of offspring were ni +

(the number of offspring whose paternal donor was not detected in the plot, i.e. the number of offspring resulting from pollen originating from outside of the plot) and nij(s) [the number of offspring of the ith mother tree whose assigned paternal donor (jth) was the same adult tree as the mother tree (synonym of selfing, ignoring possible cryptic pollen dispersal)]. The model used to describe pollen movement within the plot was ni. The categorical relationships for number and rate of offspring were ni +  + nij(s), equivalent to the total number of offspring analysed, and ai = 1 – mi – si, respectively, where ai is the rate of allogamous offspring of the ith mother tree sired by a pollen donor inside of the plot, mi is the rate of pollen dispersal from outside the plot to the ith mother tree (migration rate from outside of the plot) and si is the direct rate of selfing of the ith mother tree without considering the occurrence of the same adult tree genotype outside the plot (Table 1).

+ nij(s), equivalent to the total number of offspring analysed, and ai = 1 – mi – si, respectively, where ai is the rate of allogamous offspring of the ith mother tree sired by a pollen donor inside of the plot, mi is the rate of pollen dispersal from outside the plot to the ith mother tree (migration rate from outside of the plot) and si is the direct rate of selfing of the ith mother tree without considering the occurrence of the same adult tree genotype outside the plot (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the parameters, data and estimates used in this study

| Parameter | Datum | Rate | Derivation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Pollen attenuation parameter for the dispersal curve | |||

| X | Shape parameter of the dispersal curve | |||

| αj | Parameter from the magnitude of male fecundity for the jth adult tree in the plot | |||

| ni | Number of allogamous offspring produced by the ith mother tree | |||

|

Number of the ith mother's offspring whose paternal donors were not detected in the plot | |||

| nij(t) | Number of the ith mother's allogamous offspring sired by jth pollen donor in the plot | |||

| nij(s) | Number of offspring of the ith mother tree whose assigned paternal tree was the jth adult tree when the ith mother tree was located at the same position as the jth paternal donor (self-fertilization) | |||

| dij | Horizontal distance in metres between the ith mother tree and the jth adult tree in the plot | |||

| ai | 1 – mi – si | Rate of allogamous offspring sired by a pollen donor inside the plot | ||

| mi |

/oi /oi

|

Rate of pollen dispersal from outside the plot to the ith mother tree (migration rate from outside the plot) | ||

| si | nij(s)/oi | Direct rate of selfing of the ith mother tree without considering the occurrence of the same adult tree genotype outside the plot |

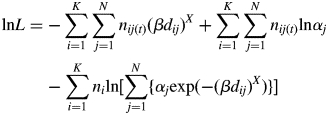

In modelling of pollen dispersal with male fecundity variation (MPM), a pollen dispersal kernel of  was assumed, where β and x were defined as the pollen dispersal parameter and the shape parameter of the dispersal curve, respectively, similar to their counterparts in the neighbourhood model (Burczyk et al., 1996; Adams, 1992). The fixed parameter (X) was then added to the kernel to modify the shape of the dispersal curve (four values of X were assumed: 0·5, 1, 1·5 and 2·0). To investigate possible improvements to the fit of the model by considering the heterogeneity of pollen production by different adult trees, a term describing the amount of pollen produced by each adult tree (αi) was included. αi was constrained by its distribution (polynomial). As for the neighbourhood model, these parameters were estimated only from pollen exchange events within the plot in the absence of selfing. The notations of the model parameters and data are summarized in Table 1. In these models the relative pollen contribution of the jth pollen donor throughout N pollen donors to the ith mother tree was expressed as

was assumed, where β and x were defined as the pollen dispersal parameter and the shape parameter of the dispersal curve, respectively, similar to their counterparts in the neighbourhood model (Burczyk et al., 1996; Adams, 1992). The fixed parameter (X) was then added to the kernel to modify the shape of the dispersal curve (four values of X were assumed: 0·5, 1, 1·5 and 2·0). To investigate possible improvements to the fit of the model by considering the heterogeneity of pollen production by different adult trees, a term describing the amount of pollen produced by each adult tree (αi) was included. αi was constrained by its distribution (polynomial). As for the neighbourhood model, these parameters were estimated only from pollen exchange events within the plot in the absence of selfing. The notations of the model parameters and data are summarized in Table 1. In these models the relative pollen contribution of the jth pollen donor throughout N pollen donors to the ith mother tree was expressed as

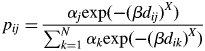

|

1 |

where pij is the expected rate of allogamous ith mother tree's offspring sired by the jth pollen donor [self-fertilization (ith tree was same tree as jth tree) was excluded]. Given the high accuracy of the parentage assignments, any candidate tree in the plot meeting the paternal criteria described above was assumed to be the true paternal tree of the offspring. Note that only one or no candidate fathers were assigned for each offspring. The likelihood function for K mother trees was expressed as

|

2 |

where nij(t) was the number of the ith mother's allogamous offspring sired by the jth pollen donor in the plot. The log-likelihood function for K mother trees was expressed as

|

3 |

This equation was solved by the quasi-Newton method (using the Solver function in MS EXCEL). To identify effects of parameters, three scenarios with variants of the models were examined by parameter fixation. Model 0 (M0) assumed a constant pollen dispersal from the source, which was expressed by assigning zero to β. M0-2 expressed male fecundity variation between the adult trees inside the plot, and was a variant of the simpler model (M0-1; constant male fecundity, αj = 1). M1 was a model to express pollen dispersal being exponentially attenuated with increasing distance (0 < β ≤ 1) and male fecundity assumed to be constant (αj = 1). M2 was a model to express pollen dispersal as exponentially attenuated with increasing distance (0 < β ≤ 1) and male fecundity variation was assumed (αj variable under polynomial distribution; see Table 4 below). We then calculated lnL for the ML estimation and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC, Akaike, 1973) for each of the models. A model with a smaller AIC value is more appropriate for explaining a given dataset than one with a larger AIC value (Sakamoto, 1991). Likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) were then applied to the combinations to evaluate the effects of pollen dispersal parameters (see Table 4). Descriptions of the parameters, data and estimates are summarized in Table 1. The confidence intervals of the parameters were estimated by bootstrapping based on 1000 iterations. The random re-sampling did not address the contribution of non-contributory paternal adult trees in the plot to the offspring population, pollen dispersal from outside the plot or cryptic pollen dispersal. Paternity assignments of each mother tree were re-sampled for each iteration.

Table 4.

All combinations of parameter settings, log-likelihoods and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values for MPM used in the paternity analyses, excluding selfing data, of both S. leprosula and S. parvifolia in the 2002 flowering season

| Model H1 | Species | Parameter setting |

Pollen attenuation |

Pollen amount |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | α | X | d.f. | lnL | AIC | H0 | p-value | d.f. | H0 | p-value | d.f. | ||

| M0-1 | SL | 0 | 1 | – | 0 | −456·31 | 912·61 | ||||||

| M0-2 | SL | 0 | αj | – | 60 | −248·44 | 616·87 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 64 | |||

| M1-1 | SL | β | 1 | 0·5 | 1 | −384·67 | 771·34 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 1 | |||

| M1-2 | SL | β | 1 | 1 | 1 | −371·96 | 745·91 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 1 | |||

| M1-3 | SL | β | 1 | 1·5 | 1 | −376·26 | 754·52 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 1 | |||

| M1-4 | SL | β | 1 | 2 | 1 | −383·88 | 769·77 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 1 | |||

| M2-1 | SL | β | αj | 0·5 | 61 | −241·78 | 605·55 | M0-2 | <0·1 % | 1 | M1-1 | <0·1 % | 64 |

| M2-2 | SL | β | αj | 1 | 61 | −231·75 | 585·51 | M0-2 | <0·1 % | 1 | M1-2 | <0·1 % | 64 |

| M2-3 | SL | β | αj | 1·5 | 61 | −228·98 | 579·95 | M0-2 | <0·1 % | 1 | M1-3 | <0·1 % | 64 |

| M2-4 | SL | β | αj | 2 | 61 | −229·19 | 580·38 | M0-2 | <0·1 % | 1 | M1-4 | <0·1 % | 64 |

| M0-1 | SP | 0 | 1 | – | 0 | −203·86 | 407·73 | ||||||

| M0-2 | SP | 0 | αj | – | 69 | −114·03 | 366·06 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 69 | |||

| M1-1 | SP | β | 1 | 0·5 | 1 | −177·52 | 357·04 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 1 | |||

| M1-2 | SP | β | 1 | 1 | 1 | −178·10 | 358·20 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 1 | |||

| M1-3 | SP | β | 1 | 1·5 | 1 | −180·87 | 363·74 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 1 | |||

| M1-4 | SP | β | 1 | 2 | 1 | −183·17 | 368·35 | M0-1 | <0·1 % | 1 | |||

| M2-1 | SP | β | αj | 0·5 | 70 | −109·39 | 358·79 | M0-2 | <1 % | 1 | M1-1 | <0·1 % | 69 |

| M2-2 | SP | β | αj | 1 | 70 | −109·66 | 359·31 | M0-2 | <1 % | 1 | M1-2 | <0·1 % | 69 |

| M2-3 | SP | β | αj | 1·5 | 70 | −110·18 | 360·36 | M0-2 | <1 % | 1 | M1-3 | <0·1 % | 69 |

| M2-4 | SP | β | αj | 2 | 70 | −110·57 | 361·14 | M0-2 | <1 % | 1 | M1-4 | <0·1 % | 69 |

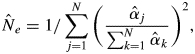

Given estimates of the paternity contribution parameters (αj) in the best-fitting model for the M2 scenario (αj assigned as a variable parameter), fertilities of individual males within the plot with respect to the mother trees can be inferred from the model, and from the estimated value of  the effective number of males in the plot siring offspring of given mother trees can be derived from

the effective number of males in the plot siring offspring of given mother trees can be derived from

|

4 |

which is modified from Burczyk et al. (1996).

RESULTS

Paternity analysis and selfing rate

The ten microsatellite markers were highly variable; 5–29 and 2–17 alleles per locus were detected in the S. leprosula and S. parvifolia samples, respectively. The observed and expected heterozygosites for S. leprosula ranged from 0·414 to 0·902 (average, 0·739) and from 0·419 to 0·895 (average, 0·797), respectively. The observed and expected heterozygosities for S. parvifolia were lower than those for S. leprosula, ranging from 0·086 to 0·814 (average, 0·637) and from 0·083 to 0·880 (average, 0·664), respectively. The high variability of the markers resulted in high theoretical exclusionary power for identifying the second parents of the offspring in the paternity analyses (0·99999 for S. leprosula and 0·99931 for S. parvifolia), which allowed paternity assignments to be performed with high resolution (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic diversity and exclusion indices for adult individuals of Shorea leprosula and S. parvifolia in the Pasoh 40-ha ecological plot

| Locus | No. of alleles | No. of adult trees surveyed | No. of heterozygotes | No. of homozygotes | Heterozygosity |

PIC* | Exclusion probability |

HWE** | Null frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | First parent | Second parent | ||||||||

| S. leprosula | |||||||||||

| sle079 | 19 | 61 | 55 | 6 | 0·902 | 0·895 | 0·878 | 0·636 | 0·778 | n.s. | −0·014 |

| sle105 | 6 | 60 | 42 | 18 | 0·700 | 0·755 | 0·714 | 0·356 | 0·537 | <0·01 | 0·034 |

| sle111 | 20 | 61 | 51 | 10 | 0·836 | 0·882 | 0·865 | 0·612 | 0·759 | n.s. | 0·024 |

| sle290 | 29 | 59 | 42 | 17 | 0·712 | 0·947 | 0·936 | 0·781 | 0·877 | <0·001 | 0·139 |

| sle294 | 8 | 61 | 35 | 26 | 0·574 | 0·647 | 0·607 | 0·245 | 0·424 | <0·001 | 0·054 |

| sle303 | 14 | 59 | 49 | 10 | 0·831 | 0·860 | 0·839 | 0·556 | 0·717 | n.s. | 0·014 |

| sle392 | 16 | 61 | 49 | 12 | 0·803 | 0·843 | 0·820 | 0·521 | 0·688 | n.s. | 0·017 |

| sle475 | 13 | 61 | 50 | 11 | 0·820 | 0·850 | 0·826 | 0·527 | 0·692 | <0·01 | 0·013 |

| shc03 | 5 | 58 | 24 | 34 | 0·414 | 0·419 | 0·391 | 0·092 | 0·237 | n.s. | −0·015 |

| shc07 | 14 | 59 | 47 | 12 | 0·797 | 0·872 | 0·852 | 0·581 | 0·737 | <0·01 | 0·043 |

| Average | 14·4 | 60 | 44·4 | 15·6 | 0·739 | 0·797 | 0·773 | 0·491 | 0·645 | 0·031 | |

| Total exclusionary power (first parent): 0·999425 | |||||||||||

| Total exclusionary power (second parent): 0·99999 | |||||||||||

| S. parvifolia | |||||||||||

| sle079 | 7 | 68 | 41 | 27 | 0·603 | 0·539 | 0·511 | 0·166 | 0·341 | n.s. | −0·072 |

| sle105 | 2 | 70 | 6 | 64 | 0·086 | 0·083 | 0·079 | 0·003 | 0·039 | n.s. | −0·013 |

| sle111 | 11 | 70 | 52 | 18 | 0·743 | 0·787 | 0·752 | 0·410 | 0·587 | n.s. | 0·029 |

| sle290 | 17 | 70 | 52 | 18 | 0·743 | 0·782 | 0·750 | 0·413 | 0·591 | <0·01 | 0·016 |

| sle294 | 7 | 70 | 39 | 31 | 0·557 | 0·630 | 0·556 | 0·212 | 0·358 | <0·001 | 0·060 |

| sle303 | 10 | 70 | 55 | 15 | 0·786 | 0·784 | 0·748 | 0·400 | 0·579 | <0·05 | −0·004 |

| sle392 | 11 | 70 | 57 | 13 | 0·814 | 0·862 | 0·841 | 0·555 | 0·716 | n.s. | 0·026 |

| sle475 | 8 | 69 | 43 | 26 | 0·623 | 0·638 | 0·603 | 0·242 | 0·424 | n.s. | 0·004 |

| shc03 | 5 | 67 | 43 | 24 | 0·642 | 0·654 | 0·603 | 0·236 | 0·408 | n.s. | 0·003 |

| shc07 | 17 | 70 | 54 | 16 | 0·771 | 0·880 | 0·863 | 0·605 | 0·754 | n.s. | 0·064 |

| Average | 9·5 | 69·4 | 44·2 | 25·2 | 0·637 | 0·664 | 0·631 | 0·324 | 0·480 | 0·011 | |

| Total exclusionary power (first parent): 0·98613 | |||||||||||

| Total exclusionary power (second parent): 0·999313 | |||||||||||

*Polymorphism information content.

**Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

All statistics were estimated from Cervus ver. 2.0 (Marshall et al., 1998).

The rates of pollen dispersal within the plot (mi) were virtually synonymous with the rate of pollen dispersal from outside the plot, because the high paternity exclusionary power of the microsatellite markers reduced the rate of cryptic pollen dispersal to a negligible level. The rates of pollen dispersal from outside the plot were very high for the offspring of some maternal trees at the margins of the plot (>70 %), and rates >50 % were even found for offspring of some maternal S. leprosula trees located near the centre of the plot. However, these rates were lower for S. parvifolia (generally less than 50 %; Table 3). Sampled offspring of S. leprosula mother trees had contributions from 1–12 (average, 5·1) paternal donors, while corresponding numbers for S. parvifolia were 2–11, with an average of 4·7 (Table 3). The lowest and highest estimated selfing rates by the paternity analysis (0·000 and 0·843) were obtained for the G0147 S. leprosula mother tree in 2001, and the G0326 S. parvifolia mother tree in 2002, respectively. The average selfing rates for the S. leprosula population were lower than those for S. parvifolia for both flowering seasons.

In 2001, the total number of offspring analysed for the two species was lower than in 2002 because of less seed masting. Moreover, the high rate of pollen dispersal from outside the plot and self-fertilization reduced the number of allogamous offspring that were paternally contributed by adult trees within the plot. These allogamous offspring were informative for estimating pollen dispersal and paternal contribution parameters in the MPM. In 2001, only 12 and 21 allogamous offspring whose paternal candidates were located inside the plot for S. leprosula and S. parvifolia, respectively, were detected. In contrast, 111 and 48 allogamous offspring with paternal candidates were located inside the plot according to the paternity analysis in the 2002 flowering year for S. leprosula and S. parvifolia, respectively. Therefore, MPM analysis was conducted only for paternity results in 2002.

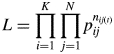

Modelling of pollen dispersal with male fecundity variation (MPM)

Using the MPM, pollen dispersal patterns and other parameters related to pollen dispersal and male fecundity were inferred. For models M0-1 and M0-2 for the two species, the null hypotheses of the likelihood ratio tests (i.e. that pollen was constantly dispersed from adult trees) could be rejected. With respect to the amount of pollen produced by different trees (parameter αj), the null hypothesis was rejected for both species. With respect to the parameters associated with the dispersal curve shape (X), for S. leprosula and S. parvifolia the AIC values indicated that models M2-3 and M2-1, which yielded exponential dispersal kernels, gave the best fits, respectively (Table 4).

Pollen dispersal pattern

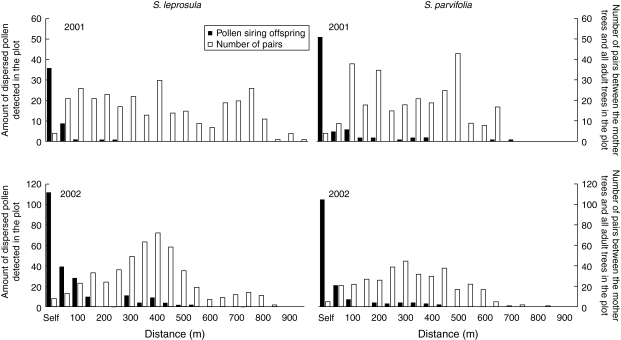

Based on paternity analysis, the overall average rate of pollen dispersal from outside the plot (mi) reached 44·5 % (Table 3). However, pollen dispersal from outside the plot could not be taken into account when attempting to quantify pollen dispersal patterns, because no information was available about the location of trees outside the plot. Nine maternal trees used for seed and seedling sampling were located at the margins of the plot, and adult trees located outside the plot boundary, but near the maternal trees, may have contributed as pollen donors. Therefore, only the data from paternal trees detected within the plot were used to describe pollen dispersal patterns. Most of the paternal donors for the two species were located within 100 m of the maternal trees. However, long-distance pollen dispersal exceeding 700 m was detected for S. leprosula, but not for S. parvifolia. It should be noted that most of the mother S. leprosula trees from which seeds could be collected were located at the margin of the plot, and thus received high proportions of pollen from outside the plot. A high frequency of pollen dispersal occurred over distances ranging from 250 to 450 m for S. parvifolia (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The amount of pollen siring offspring detected by the paternity analysis (black bar) and the number of pairs between the mother trees and all adult trees (open bar) for every 50-m distance class in S. leprosula and S. parvifolia.

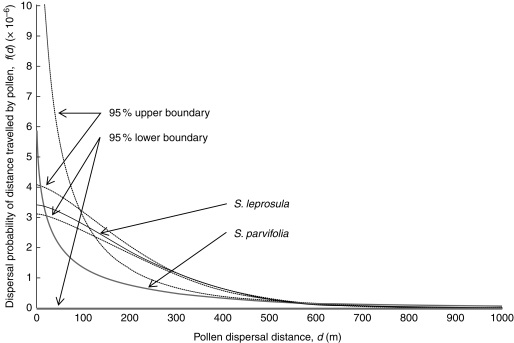

Due to the lower number of allogamous offspring with paternal pollen donors within the plot in 2001, the 95 % confidence intervals of these dispersal parameters (obtained by bootstrapping) were wider in 2001 than in 2002 (data not shown). Although high rates of pollen migration from outside the plot and self-fertilization for both species in 2002 were detected, the larger sample sizes for both species in 2002 allowed dispersal curve parameters with relatively narrow 95 % confidence intervals to be estimated (Fig. 4). The AIC values indicated that the different shape parameters (X = 1·5 and 0·5) for exponential distribution curves provided the best fits to the S. leprosula and S. parvifolia data in 2002, respectively. The dispersal curves for S. leprosula in 2002 indicated that there were higher rates of pollen exchange within the middle distance range (over distances of less than approx. 300 m) than for S. parvifolia, and the half-lives of their dispersal probabilities were 219·7 m (S. leprosula) and 22·9 m (S. parvifolia); however, these dispersal curves had different tail forms (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Estimated normalized pollen dispersal curves derived from the modelling of pollen dispersal with male fecundity variation (MPM). The normalized function was derived from Clark et al. (1999). Black and grey lines indicate dispersal curves derived from the parameters when the MPM selected optimal conditions for S. leprosula and S. parvifolia in 2002, as indicated. Dotted lines represent 95 % upper and lower confidence intervals obtained by bootstrap analysis based on 1000 iterations.

Male fecundity variation

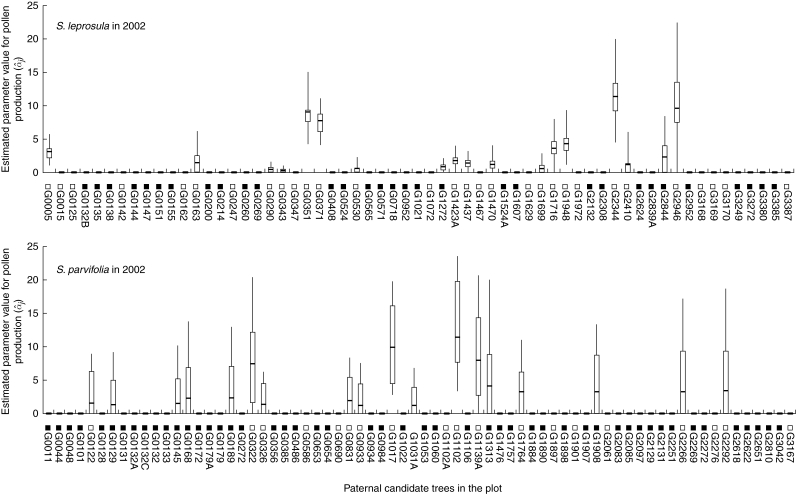

Although we assigned αj parameter values to the jth adult tree from all trees with dbh exceeding 30 cm, only those adult trees contributing to offspring samples as paternal donors, according to the paternity analysis, were assigned values greater than zero. The 95 % confidence interval obtained by the bootstrap procedure showed that estimation of αj in 2001 was uncertain, because the number of informative allogamous offspring was low (data not shown). In 2002, the larger number of informative allogamous offspring reduced the 95 % confidence interval. However, the confidence intervals for some paternal donors were still large. Hence, only seven and four adult S. leprosula and S. parvifolia trees, respectively, were assigned bootstrap-supported values of the parameter that were significantly different from 0 in 2002. The effective numbers of males in the plot siring offspring with the mother trees [ ] were 8·790 (0·144) for S. leprosula and 10·903 (0·156) for S. parvifolia in 2002. Thus, although heterogeneity in the production of effective pollen occurred in these mating events, the estimates of αj values had large 95 % confidence intervals in some cases (Fig. 5).

] were 8·790 (0·144) for S. leprosula and 10·903 (0·156) for S. parvifolia in 2002. Thus, although heterogeneity in the production of effective pollen occurred in these mating events, the estimates of αj values had large 95 % confidence intervals in some cases (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Estimates of individual male fecundity (α̂j; horizontal lines within bars). The bars represent the 95 % upper and lower confidence intervals, and the lines above and below represent maximum and minimum estimates obtained by bootstrap analysis based on 1000 iterations. The open and closed squares before the adult tree names represent flowering and non-flowering trees confirmed by field observation, respectively.

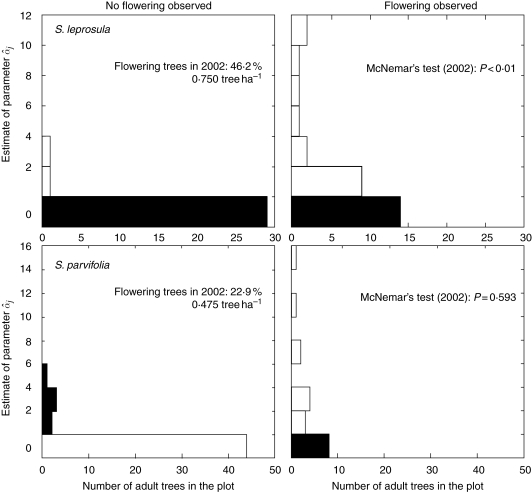

Field observations of the flowering of each tree of the two species during the two flowering seasons showed that 40·0 and 46·2 % adult S. leprosula and 45·8 and 22·9 % adult S. parvifolia trees flowered in 2001 and 2002, respectively. To test for correlations between field observations of flowering trees and the parameter  estimated by the MPM, McNemar's test was applied. In this statistical test,

estimated by the MPM, McNemar's test was applied. In this statistical test,  estimators were derived from M2-3 for S. leprosula, and M2-1 in 2002 for S. parvifolia, as these models yielded the highest AIC values for the models (Table 4). The

estimators were derived from M2-3 for S. leprosula, and M2-1 in 2002 for S. parvifolia, as these models yielded the highest AIC values for the models (Table 4). The  values of all adult trees were converted to nominal data (flowering or not flowering) and were then compared with field observation data. Although the null hypothesis (that there was no difference between field observations and the nominal parameter) was rejected for S. leprosula in 2002, the null hypothesis was not rejected for S. parvifolia in 2002 (Fig. 6).

values of all adult trees were converted to nominal data (flowering or not flowering) and were then compared with field observation data. Although the null hypothesis (that there was no difference between field observations and the nominal parameter) was rejected for S. leprosula in 2002, the null hypothesis was not rejected for S. parvifolia in 2002 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The relationship between the estimated value of α̂j for each adult tree and the flowering observations reported from the field. The histograms show the distributions of α̂j for each adult tree in the ‘no flowering’ and ‘flowering’ categories based on field observations, as indicated. The black and white bars indicate the inconsistency and consistency between parameter estimates by the MPM and field observations, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Modelling of pollen dispersal with male fecundity variation (MPM)

The MPM is a modified form of the neighbourhood model (Adams, 1992; Burczyk et al., 1996), which estimates pollen dispersal patterns from likelihoods, based on Mendelian transition probabilities that fertilization by three types of pollen sources have given rise to offspring with observed genotypes: (1) self-fertilization; (2) pollination by a distant, unknown father located outside the local population; and (3) pollination by a local, genotyped father (Burczyk et al., 2002). The present model provides estimates of the male fecundity from potential pollen donors to each mother tree considering pollen dispersal kernels. As Burczyk et al. (2002) pointed out, if paternity assignments are not reliable, then the application of models such as the MPM will not provide reliable estimates of pollen dispersal curves or ecologically and genetically relevant mating success parameters. However, recent advances in molecular biology enable the identification and use of highly polymorphic microsatellite markers, and thus accurate genotyping. Used in conjunction with such markers, the MPM allows direct parameter estimates to be made because, unlike the neighbourhood model, it is not necessary to calculate Mendelian transition probabilities.

Devlin & Ellstrand (1990) and Burczyk and Chybicki (2004) have suggested that due to low exclusion probabilities and the likelihood that large amounts of immigrating pollen will be genetically compatible with local paternal trees (leading to high levels of cryptic gene flow), immigration levels may often be underestimated in pollen dispersal analyses. However, in the present study relatively high exclusion power (for candidate second parents) and low densities of adult trees in the tropical forest allowed precise paternity exclusion. Nevertheless, data acquired from the offspring of several trees, particularly for S. leprosula, provided evidence of high rates of pollen immigration from outside the plot (Table 3), mainly associated with mother trees located at the plot margins (Fig. 1). Therefore, the parameters for such trees might be somewhat different from the real values at the landscape level, as pollen dispersal from outside the plot was not taken into account when estimating these parameters.

Pollen dispersal patterns

Various attempts have been made to elucidate pollen dispersal patterns of several tree species in palaeo-tropical and neo-tropical regions (e.g. Konuma et al., 2000; Kenta et al., 2004; Ward et al., 2005). First, tracking studies of rare allozyme alleles and fractional paternity analysis have shown that long-distance pollen dispersal can occur over hundreds of metres in low-density tree species that are pollinated by large insects, such as bees (Hamrick and Murawski, 1990; Boshier et al., 1995; Loveless et al., 1998). In addition, Stacy et al. (1996) have shown that pollen dispersal distances of tree species pollinated by small insects, including beetles, small bees and moths, exceeded the mean distances to their nearest potential mates, violating the nearest-neighbour mating hypothesis (Levin and Kerster, 1974). We found evidence of substantial long-distance pollen dispersal for both studied species during two flowering events (Fig. 3). However, the estimated pollen dispersal curves showed a rapid decline with increasing distance from the pollen sources in their immediate vicinity (Fig. 4). Similarly, previous studies on three Shorea species also found evidence of a rapid decline in pollen dispersal (Lee et al., 2006; Fukue et al., 2007; Naito et al., 2008). Shorea produces small, hermaphroditic flowers and is pollinated by small insects, such as thrips and small beetles belonging to the families Chrysomelidae and Curculionidae (Appanah and Chan, 1981; Momose et al., 1998; Sakai et al., 1999). During flowering seasons, many thrips have been observed visiting flowers, and some carnivorous shield bugs have been attracted to thrips as a food source (T. K. Kondo et al., Hiroshima University, Japan, pers. comm.). Hence, these small beetles and shield bugs might contribute to the infrequent long-distance pollen dispersal observed in Shorea species. Thrips possibly carry pollen by floating long distances on air currents, but this frequency is unlikely to exceed the range of the estimated dispersal curves. Alternatively, most of the pollen might be carried by thrips from the pollen donor trees, which might contribute to the high rate of self-fertilization and the rapid decline in the immediate vicinity of the pollen source seen in the pollen dispersal curves obtained for S. leprosula and S. parvifolia (Table 3 and Fig. 4).

In 2002, different shapes to the optimal dispersal curves was detected between S. leprosula and S. parvifolia. The flower structure and physiological and ecological features of the two species are similar; therefore, the apparent differences in the dispersal curves of the two species are presumably due to differences in their flowering tree densities. Comparison of two pollen dispersal curves in 2002 showed that the probability of pollen dispersal decreased rapidly with increasing distance, but a low probability of pollen dispersal was detected in the further range of distance in S. parvifolia (L-shaped dispersal pattern), which was probably caused by the lower flowering tree density of S. parvifolia in 2002 (0·213 vs. 0·725 trees ha−1 in S. leprosula; Fig. 4). By contrast, the selfing rate of S. parvifolia in 2002 was higher than of S. leprosula (Table 3). This observation was consistent with previous observations in Shorea species, i.e. that the lower flowering tree density surrounding mother trees caused increased selfing (Murawski et al., 1994b; Nagamitsu et al., 2001; Obayashi et al., 2002; Fukue et al., 2007; Naito et al., 2008). Therefore, the lower flowering tree density would promote an L-shaped pollen dispersal pattern and increased selfing due possibly to allogamous pollen resource limitation.

Male fecundity variation estimated by the MPM and flowering observations in the field

There were strong, significant inconsistencies between the  estimates for the adult trees and the field observations of the flowering trees of S. leprosula in 2002 (Fig. 6). First, no flowering of some trees with

estimates for the adult trees and the field observations of the flowering trees of S. leprosula in 2002 (Fig. 6). First, no flowering of some trees with  values exceeding 0 was detected in the field, probably due to the inherent limitations of observing flowering trees from the ground (notably, the failure to detect flowering because dipterocarps sometimes only produce flowers on certain, hidden branches). In addition, it is difficult to quantify the magnitude of flowering from field observations. Secondly, some adult trees bloomed even though their

values exceeding 0 was detected in the field, probably due to the inherent limitations of observing flowering trees from the ground (notably, the failure to detect flowering because dipterocarps sometimes only produce flowers on certain, hidden branches). In addition, it is difficult to quantify the magnitude of flowering from field observations. Secondly, some adult trees bloomed even though their  values were 0, possibly due to sampling insufficient numbers of offspring from mother trees and/or sampling mother trees. Although sufficient offspring samples were collected to provide an accurate estimate of

values were 0, possibly due to sampling insufficient numbers of offspring from mother trees and/or sampling mother trees. Although sufficient offspring samples were collected to provide an accurate estimate of  in the population, an inconsistency between

in the population, an inconsistency between  and flowering observations could have occurred because

and flowering observations could have occurred because  is a composite parameter that describes the probability of paternal contribution in the absence of any distance effect, and therefore should be affected by various ecological factors, such as flowering phenology, pollinator behaviour and wind direction, that were not addressed in this study.

is a composite parameter that describes the probability of paternal contribution in the absence of any distance effect, and therefore should be affected by various ecological factors, such as flowering phenology, pollinator behaviour and wind direction, that were not addressed in this study.

The magnitude of general flowering possibly affects pollinator dynamics and behaviour, which would subsequently affect mating patterns, such as mating system and male fecundity variation. The flowering tree densities of S. leprosula in the two flowering seasons were almost the same (0·650 and 0·750 trees ha−1 in 2001 and 2002, respectively), whereas the density of S. parvifolia in 2001 (0·950 trees ha−1) was higher than in 2002 (0·475 trees ha−1). The variation of male fecundity among adult trees and the effective number of paternal trees were expected to be smaller and larger, respectively, when flowering tree density was high, because the larger number of paternity candidates should contribute to mating events. However, a larger effective number of paternal trees (shown as  and

and  /N statistics) for both species in 2002 was detected (

/N statistics) for both species in 2002 was detected ( and

and  /N statistics in 2001 not shown) and pollen dispersal activity of S. parvifolia in 2002 was not reduced (Figs 2 and 3). Numata et al. (2003) summarized the magnitude of mass flowering events in the Pasoh FR between 1976 and 2002. They categorized the 2001 flowering event, in which they found 24 % of the dipterocarp trees found to be in bloom, as a sporadic flowering event, while 55 % of the dipterocarp trees bloomed in 2002 and this was categorized as a mass flowering event. It was reported that synchronized flowering of many species caused an increase in pollinator activity through immigration and population growth (Sakai, 2002). This phenomenon might promote active pollen dispersal for the two species in 2002 (Figs 1 and 2); consequently, a lower variation of male fecundity among adult trees and a larger effective number of paternal trees in 2002 were detected. Therefore, we need to consider the magnitude of general flowering, which increases activity and population size of pollinators, to explain the breeding pattern of lowland dipterocarp forest.

/N statistics in 2001 not shown) and pollen dispersal activity of S. parvifolia in 2002 was not reduced (Figs 2 and 3). Numata et al. (2003) summarized the magnitude of mass flowering events in the Pasoh FR between 1976 and 2002. They categorized the 2001 flowering event, in which they found 24 % of the dipterocarp trees found to be in bloom, as a sporadic flowering event, while 55 % of the dipterocarp trees bloomed in 2002 and this was categorized as a mass flowering event. It was reported that synchronized flowering of many species caused an increase in pollinator activity through immigration and population growth (Sakai, 2002). This phenomenon might promote active pollen dispersal for the two species in 2002 (Figs 1 and 2); consequently, a lower variation of male fecundity among adult trees and a larger effective number of paternal trees in 2002 were detected. Therefore, we need to consider the magnitude of general flowering, which increases activity and population size of pollinators, to explain the breeding pattern of lowland dipterocarp forest.

In 2002, the densities of flowering S. leprosula and S. parvifolia trees were 0·75 and 0·23 ha−1, respectively. However, a previous study conducted on a neo-tropical tree species showed that at sites where flowering trees were clumped, most mating occurred between near neighbours, although long-distance pollen dispersal, well beyond the nearest reproductive neighbours, was recorded at sites where flowering trees were evenly spaced (Stacy et al., 1996). In addition, reductions in tree density due to logging have been found to have an effect in increasing the effective number of pollen donors of the insect-pollinated tree species Cornus florida (Sork et al., 2005). Cloutier et al. (2007) found selective logging had little effect on either the mating system or pollen dispersal of the Amazonian tree species Carapa guianensis. Nevertheless, we speculate that any reduction in the abundance of flowering trees may hinder pollinators from flying between flowering trees, which may consequently increase the selfing rate and prevent active pollination in the middle distance range (Table 3, Figs 3 and 4). Although low-frequency, long-distance pollen dispersal might result from the activities of small beetles (Momose et al., 1998; Sakai et al., 1999), very high-frequency pollen dispersal within the middle distance range (within a few hundred metres) might occur through the movement of thrips (Appanah and Chan, 1981). This suggests that the mating system of tree species whose pollen dispersal is mediated by weak-flying insects, particularly Shorea spp., might be more sensitive to reductions in tree density (and thus in levels of pollen reaching distant trees) than tree species with pollination mediated by energetic insects. Therefore, the mating system of Shorea species will be affected by reductions in tree density, with selective logging being the main cause of tree density reductions in natural forests (Obayashi et al., 2002). Thus, appropriate tree density controls need to be developed and incorporated into forest management plans to ensure the remaining genetic resources are sustainably utilized and managed for future generations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the staff of the Pasoh Field Research Station and the Genetic Laboratory of the Forest Research Institute, Malaysia, for their assistance in the field and laboratory, especially Ms D. Mariam, Ms Nor Salwah A. W. and Ms Nurl Hudaini Mamat for DNA extraction. We also thank Mr E. S. Quah and Ms K. Obayashi for their assistance in establishing the 40-ha ecological plot and Ms M. Koshiba for her assistance with laboratory work. We thank Dr Y. Naito and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the manuscript. The study was partly supported by the Global Environment Research Program supported by the Ministry of Environment in Japan (grant no. E-4) and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 18255010) provided by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adams WT. Gene dispersal within forest tree populations. In: Adams WT, Strauss SH, Copes DL, Griffin AR, editors. Population genetics of forest trees. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 1992. pp. 217–240. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike L. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood pronciple. In: Petrov BN, Csaki F, editors. 2nd International Symposium on Information Theory. Budapest: Akademiai; 1973. pp. 610–623. [Google Scholar]

- Appanah S, Chan HT. Thrips: the pollinators of some dipterocarps. The Malaysian Forester. 1981;44:234–252. [Google Scholar]

- Bacles CFE, Burczyk J, Lowe AJ, Ennos RA. Historical and contemporary mating patterns in remnant populations of the forest tree Fraxinus excelsior L. Evolution. 2005;59:979–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawa KS. Breeding systems of tree species of a lowland tropical community. Evolution. 1974;28:85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1974.tb00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawa KS, Bullock SH, Perry DR, Coville RE, Grayum MH. Reproductive biology of tropical lowland rain forest trees. 2. Pollination systems. American Journal of Botany. 1985;72:346–356. [Google Scholar]

- Boshier DH, Chase MR, Bawa KS. Population genetics of Cordia alliodora (Boraginaceae), a neotropical tree. 3. Gene flow, neighborhood, and population substructure. American Journal of Botany. 1995;82:484–490. [Google Scholar]

- Burczyk J, Chybicki IJ. Cautions on direct gene flow estimation in plant populations. Evolution. 2004;58:956–963. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burczyk J, Koralewski TE. Parentage versus two-generation analyses for estimating pollen-mediated gene flow in plant populations. Molecular Ecology. 2005;14:2525–2537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burczyk JL, Prat D. Male reproductive success in Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) France: the effects of spatial structure and flowering characteristics. Heredity. 1997;79:638–647. [Google Scholar]

- Burczyk J, Adams WT, Shimizu JY. Mating patterns and pollen dispersal in a natural knobcone pine (Pinus attenuata Lemmon) stand. Heredity. 1996;77:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Burczyk J, Adams WT, Moran GF, Griffin AR. Complex patterns of mating revealed in a Eucalyptus regnans seed orchard using allozyme markers and the neighbourhood model. Molecular Ecology. 2002;11:2379–2391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JS, Silman M, Kern R, Macklin E, HilleRisLambers J. Seed dispersal near and far: patterns across temperate and tropical forests. Ecology. 1999;80:1475–1494. [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier D, Kanashiro M, Ciampi AY, Schoen DJ. Impact of selective logging on inbreeding and gene dispersal in an Amazonian tree population of Carapa guianensis Aubl. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:797–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit R, Hubbell SP, Lafrankie JV, et al. Species-area and species-individual relationships for tropical trees: a comparison of three 50-ha plots. Journal of Ecology. 1996;84:549–562. [Google Scholar]

- Condit R, Ashton PS, Manokaran N, LaFrankie JV, Hubbell SP, Foster RB. Dynamics of the forest communities at Pasoh and Barro Colorado: comparing two 50-ha plots. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences. 1999;354:1739–1748. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corner EJH. The evolution of tropical forest. In: Huxley JS, Hardy AC, Ford EB, editors. Evolution as a process. London: Allen & Unwin; 1954. pp. 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TJ. The estimation of neighborhood parameters for plant populations. Heredity. 1984;52:273–283. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Ellstrand NC. The development and application of a refined method for estimating gene flow from angiosperm paternity analysis. Evolution. 1990;44:248–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb05195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Clegg J, Ellstrand NC. The effect of flower production on male reproductive success in wild radish populations. Evolution. 1992;46:1030–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1992.tb00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennos RA. Estimating the relative rates of pollen and seed migration among plant populations. Heredity. 1994;72:250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov AA. Structure of tropical rain forest and speciation in humid tropics. Journal of Ecology. 1966;54:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fukue Y, Kado T, Lee SL, Ng KKS, Muhammad N, Tsumura Y. Effects of flowering tree density on the mating system and gene flow in Shorea leprosula (Dipterocarpaceae) in Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Plant Research. 2007;120:413–420. doi: 10.1007/s10265-007-0078-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick JL, Murawski DA. The breeding structure of tropical tree populations. Plant Species Biology. 1990;5:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- He FL, Legendre P, LaFrankie JV. Distribution patterns of tree species in a Malaysian tropical rain forest. Journal of Vegetation Science. 1997;8:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kenta T, Isagi Y, Nakagawa M, Yamashita M, Nakashizuka T. Variation in pollen dispersal between years with different pollination conditions in a tropical emergent tree. Molecular Ecology. 2004;13:3575–3584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein EK, Desassis N, Oddou-Muratorio S. Pollen flow in the wildservice tree, Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz. IV. Whole interindividual variance of male fecundity estimated jointly with the dispersal kernel. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:3323–3336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konuma A, Tsumura Y, Lee CT, Lee SL, Okuda T. Estimation of gene flow in the tropical-rainforest tree Neobalanocarpus heimii (Dipterocarpaceae), inferred from paternity analysis. Molecular Ecology. 2000;9:1843–1852. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Wickneswari R, Mahani MC, Zakri AH. Mating system parameters in a tropical tree species, Shorea leprosula Miq. (Dipterocarpaceae), from Malaysian lowland dipterocarp forest. Biotropica. 2000;32:693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Tani N, Ng KKS, Tsumura Y. Isolation and characterization of 20 microsatellite loci for an important tropical tree Shorea leprosula (Dipterocarpaceae) and their applicability to S. parvifolia. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2004;4:222–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Ng KKS, Saw LG, et al. Linking the gaps between conservation research and conservation management of rare dipterocarps: a case study of Shorea lumutensis. Biological Conservation. 2006;131:72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA, Kerster HW. Gene flow in seed plants. Evolutionary Biology. 1974;7:139–200. [Google Scholar]

- Loveless MD, Hamrick JL, Foster RB. Population structure and mating system in Tachigali versicolor, a monocarpic neotropical tree. Heredity. 1998;81:134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Manokaran N, LaFrankie JVJ. Stand structure of Pasoh forest reserve: a lowland rain forest in peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Tropical Forest Science. 1990;3:14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall TC, Slate J, Kruuk LEB, Pemberton JM. Statistical confidence for likelihood-based paternity inference in natural populations. Molecular Ecology. 1998;7:639–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meagher TR. Analysis of paternity within a natural population of Chamaelirium luteum. 2. Patterns of male reproductive success. American Naturalist. 1991;137:738–752. [Google Scholar]

- Momose K, Yumoto T, Nagamitsu T, et al. Pollination biology in a lowland dipterocarp forest in Sarawak, Malaysia. I. Characteristics of the plant–pollinator community in a lowland dipterocarp forest. American Journal of Botany. 1998;85:1477–1501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murawski DA, Hamrick JL. The effect of the density of flowering individuals on the mating systems of 9 tropical tree species. Heredity. 1991;67:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Murawski DA, Dayanandan B, Bawa KS. Outcrossing rates of 2 endemic Shorea species from Sri-Lankan tropical rain forests. Biotropica. 1994;a 26:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Murawski DA, Gunatilleke I, Bawa KS. The effects of selective logging on inbreeding in Shorea megistophylla (Dipterocarpaceae) from Sri-Lanka. Conservation Biology. 1994;b 8:997–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Thompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Research. 1980;8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamitsu T, Ichikawa S, Ozawa M, et al. Microsatellite analysis of the breeding system and seed dispersal in Shorea leprosula (Dipterocarpaceae) International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2001;162:155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Naito Y, Konuma A, Iwata H, et al. Selfing and inbreeding depression in seeds and seedlings of Neobalanocarpus heimii (Dipterocarpaceae) Journal of Plant Research. 2005;118:423–430. doi: 10.1007/s10265-005-0245-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito Y, Kanzaki M, Iwata H, et al. Density-dependent selfing and its effects on seed performance in a tropical canopy tree species, Shorea acuminata (Dipterocarpaceae) Forest Ecology and Management. 2008;256:375–383. [Google Scholar]

- Numata S, Yasuda M, Okuda T, Kachi N, Noor NSM. Temporal and spatial patterns of mass flowerings on the Malay Peninsula. American Journal of Botany. 2003;90:1025–1031. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.7.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi K, Tsumura Y, Ihara-Ujino T, et al. Genetic diversity and outcrossing rate between undisturbed and selectively logged forests of Shorea curtisii (Dipterocarpaceae) using microsatellite DNA analysis. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2002;163:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Oddou-Muratorio S, Klein EK, Austerlitz F. Pollen flow in the wildservice tree, Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz. II. Pollen dispersal and heterogeneity in mating success inferred from parent–offspring analysis. Molecular Ecology. 2005;14:4441–4452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S. General flowering in lowland mixed dipterocarp forests of South-east Asia. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2002;75:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S, Momose K, Yumoto T, Kato M, Inoue T. Beetle pollination of Shorea parvifolia (section Mutica, Dipterocarpaceae) in a general flowering period in Sarawak, Malaysia. American Journal of Botany. 1999;86:62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto Y. Categorical data analysis by AIC. Tokyo: KTK; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sork VL, Smouse PE, Apsit VJ, Dyer RJ, Westfall RD. A two-generation analysis of pollen pool genetic structure in flowering dogwood, Cornus florida (Cornaceae), in the Missouri Ozarks. American Journal of Botany. 2005;92:262–271. doi: 10.3732/ajb.92.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy EA, Hamrick JL, Nason JD, Hubbell SP, Foster RB, Condit R. Pollen dispersal in low-density populations of three neotropical tree species. American Naturalist. 1996;148:275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Sun IF, Chen YY, Hubbell SP, Wright SJ, Noor N. Seed predation during general flowering events of varying magnitude in a Malaysian rain forest. Journal of Ecology. 2007;95:818–827. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y, Ichikawa S, Konuma A, et al. Comparison of the fine-scale genetic structure of three dipterocarp species. Heredity. 2004;92:323–328. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujino T, Kawahara T, Tsumura Y, Nagamitsu T, Yoshimaru H, Ratnam W. Development and polymorphism of simple sequence repeat DNA markers for Shorea curtisii and other Dipterocarpaceae species. Heredity. 1998;81:422–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.1998.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M, Dick CW, Gribel R, Lowe AJ. To self, or not to self … A review of outcrossing and pollen-mediated gene flow in neotropical trees. Heredity. 2005;95:246–254. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Isolation by distance under diverse systems of mating. Genetics. 1946;31:39–59. doi: 10.1093/genetics/31.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]