Abstract

This paper examines the community’s perspectives and perceptions on quality of health care delivery in two Uganda districts. The paper addresses community concerns on service quality. It focuses on the poor because they are a vulnerable group and often bear a huge burden of disease. Community views were solicited and obtained using eight focus group discussions, six in-depth and 12 key informant interviews. User perceptions and definitions of the quality of health services depended on a number of variables related to technical competence, accessibility to services, interpersonal relations and presence of adequate drugs, supplies, staff, and facility amenities. Results indicate that service delivery to the poor in the general population is perceived to be of low quality. The factors that were mentioned as affecting the quality of services delivered were inadequate trained health workers, shortage of essential drugs, poor attitude of the health workers, and long distances to health facilities. This paper argues that there should be an improvement in the quality of health services with particular attention being paid to the poor. Despite wide focus on improvement of the existing infrastructure and donor funding, there is still low satisfaction with health services and poor perceived accessibility.

Keywords: quality, health care, poor, community, perceptions, utilization

Introduction

Health services in Uganda are delivered by public, private for profit (PFP) and private not-for-profit (PNFP) facilities. A minority of the population also seek care from traditional healers (spiritual healers, bone setters, and herbalists). The public health facilities are expected to provide services to all people without discrimination at no charge.

The quality of health services delivered in public, PFP, and PNFP facilities has been affected by several factors including the distance to health facilities, availability of drugs, equipment, and training of health workers.1,2 Some attempts have been made by the Ministry of Health (MOH) to improve the quality of services. These include, among others, building more health facilities, providing more drugs, recruiting more health workers and training health workers through continuing medical education. The dimensions of quality that relate to client satisfaction affect the health and well being of the community. Patient satisfaction is one of the factors that influence whether a person seeks medical advice, complies with treatments and maintains a relationship with the provider/health facility.3 It is hypothesized that the clients’ satisfaction is likely to be linked to their perception of a quality service. This study therefore set out to investigate the users’ perception of a quality service.

Health quality experts have defined quality in various ways. Donabedian,4 one of the most widely recognized experts on quality of health care research defined quality care as “that kind of care which is expected to maximize an inclusive measure of patient welfare, after one has taken account of the balance of expected gains and losses that attend the process of care in all its parts.” To Donabedian, quality is both technical and interpersonal. He further stated that quality involves more than just outcomes and proposed three distinct factors: structure, process and outcomes. Structure refers to the facility such as a hospital or clinic, its safety, cleanliness, and availability of equipment. Process refers to the medical staff’s use of the structure. Outcomes refer to the patient getting well or at least getting no sicker than without intervention.4 He also gives seven attributes of health care that define quality as efficacy; effectiveness, efficiency, optimality, acceptability, legitimacy and equity.4

According to Brawley,3 for the client the most important dimensions of quality are technical competence, interpersonal relations, accessibility, and amenities. Technical competence refers to the skills and actual performance of the health providers in regard to examinations, consultations and other technical procedures. The interaction between the provider and the client comprises the category of interpersonal relations. Accessibility for the client means that the health care services are unrestricted by barriers such as geography, cost, language, and times when the facilities are open. Finally, amenities refer to a client’s perception of the physical health care facility, as well as supplies and equipment within the facility.3

This study focuses on the poor and the vulnerable. One measure that is commonly used to define the poor is the one used to identify the poor in sample surveys in low-income countries: that is based on a composite measure of total household consumption per member (with adjustments for household size and composition). “Poor people” are then defined as those living in households below a particular threshold of this measure of consumption, such as below $1 in the case of the World Bank or below a nationally defined level.5 In Uganda, the poor are defined as the percentage of individuals estimated to be living in households with real private consumption per adult equivalent below the poverty line for their rural or urban sub-region.6 According to the Uganda Participatory Poverty Assessment Programme (UPPAP), Ugandans draw a distinction between individual and community-level poverty. At the personal level, poverty in Uganda is defined as inability to meet the basic necessities of life, poor access and quality of social services, and inadequate infrastructure. Thus a person or household is considered to be poor when he/it is unable to meet basic needs, such as clothing, soap, health care, school tuition, decent housing, paraffin fuel for light.7

On the other hand, vulnerability focuses on risk, insecurity, and the ability to manage risk and includes those who are likely to become poor in the future due to an unexpected shock, those who will remain poor and those who fall deeper into poverty.8,9 The Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development (2002) identified four sources of vulnerability: economic, demographic, political, and sociocultural. The vulnerability arising from economic/livelihood risks and demographic factors are the most relevant to this study. The vulnerability from economic/livelihood risks includes those who are currently poor (living below the poverty line) and those who are potentially poor. This latter group could be pushed into poverty anytime. Vulnerability from demographic factors include permanent vulnerability that is attached to specific fixed personal characteristics (gender, lifelong physical or mental disability), periodic vulnerability associated with specific lifestyle stages (pregnancy, lactation, old age); and that associated with certain forms of household composition (single parents, child-headed households, elderly headed households).10

This study was designed to investigate user perceptions, definitions, and preferences with regard to quality health care with a focus on the poor and vulnerable in order to provide information for health managers to provide services that are more responsive to the needs of the poor and vulnerable. Specifically we set out to; a) explore user perceptions of a quality service; b) identify the factors that affect perceived quality of services; c) assess community perceptions on how quality affects their utilization of health services; and d) identify areas where users would like to see improvement in quality of services.

Participants and methods

We used participatory research methods to elicit community perspectives and perceptions on quality of health care. The study was conducted in the Iganga and Bushenyi districts located in eastern and western Uganda, respectively.

Study participants were purposively selected for the focus group discussions (FGDs), in-depth interviews (IDI), and key informant interviews (KII). The criteria used for their selection included their socioeconomic status, age (above 18) sex (both males and females), presence or absence of physical disability, marital status (widowed or divorced), and their occupation.

Twelve key informant interviews were conducted with opinion leaders in the community, local politicians, and health workers. The in-depth interviews and the focus group discussions were held among the poor and vulnerable. They were identified with the help of local community leaders who were familiar with the members of the community and therefore able to identify the poor and the vulnerable following a pre-determined criterion. This criterion was developed by the research team in collaboration with the community leaders. According to this criterion, the poor were identified as those who had a low socioeconomic status. Their status was assessed based upon several factors which included ability to afford decent housing (assessed based on the type of material that was used to construct the roof, walls and floor of their house), whether they were employed or not, whether they had possessions or assets such as land, bicycles, radios, and whether they were able to meet basic needs such as clothes, food, health care, and school tuition. The vulnerable were identified based on the presence of vulnerability arising from economic and demographic factors. The specific criteria used included their socioeconomic status, age (the elderly), those with physical disability, and those who were widowed and orphaned. Six IDIs were conducted with vulnerable members of the population, including one orphan, two elderly, one widow, and two physically disabled persons.

Separate focus group discussions (FGDs) for males (4) and females (4) were conducted, made up of 6–12 participants. Eight focus group discussions were held in total, four FGDs in Iganga District from eastern Uganda representing a poor area, and four FGDs in Bushenyi District from western Uganda, representing a rich area. According to the results of the 2005/2006 Uganda National Household Survey 20.5% of those in the western region where living below the poverty line compared to 35.9 % of those in the eastern region.

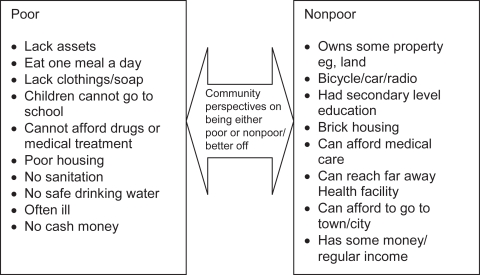

To validate the criteria that was used to select the poor, a definition was explored as to who is poor during the focus group discussions. It was found that the poor were perceived to be lacking in material goods and unable to afford services such as education and medical treatment as well as regular meals. This was in agreement with the criteria that had been used to select the poor. Figure 1 shows how community members defined the poor and either nonpoor or better off.

Figure 1.

Community perspectives of the poor and nonpoor based on community responses from Iganga and Bushenyi districts.

The gender problem tree analysis technique was used to elicit perceptions on the origin and manifestation of problems of low quality services from the perspectives of the different sexes.

All data was transcribed from the recordings, translated and notes typed into text files. Using the raw data, an analytical framework and codes were developed by the research team. Two researchers then coded the transcripts independently. One of the two researchers then compared the coding of the transcripts. When the coding for particular segments of the transcripts differed the two researchers met and discussed the respective section, and a compromise was reached on which codes to use. The coded transcripts were then entered into NUD*IST (version six; QSR International Pty. Ltd. Melbourne, Australia) software. The data was analyzed using content analysis and latent analysis techniques.

Ethical clearance

This exploratory research was conducted as part of formative research for the Future Health Systems Research Program Consortium. The protocol was reviewed by the MUSPH Institutional Review Board on September 12, 2006 and was approved by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology on December 11, 2006.

Results

A total of 18 respondents were interviewed and eight FGD’s (70 participants) conducted. Of the KI’s, four were opinion leaders and four local politicians, while four were health workers. IDIs were done with six vulnerable members of the community.

We report the findings in relation to the main concern of this paper which was to elicit community members’ perceptions and definitions of quality and their preferences with regard to access to quality health care.

User perceptions and definition of quality

Respondents viewed and rated quality of health services either as poor or good. The factors and considerations used to assess the quality of health care included availability of amenities such as infrastructure, clean water, supply of sufficient equipment and supplies, good interpersonal relationships as well as accessibility to services for vulnerable populations, referral and preventive services. These are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Perceptions about good and poor quality services

| Good quality services | Poor quality services |

| Good sanitation in the facilities | Poor sanitation in the facilities |

| Sufficient health workers | Inadequate health workers |

| Sufficient drugs, supplies and equipment | Shortages of drugs, supplies and equipment |

| Short waiting time | Long waiting time |

| Counselling about preventive care | Inadequate/no counselling on preventive care |

| Services for the poor and elderly are available | Lack services for the poor and elderly |

| Good referral systems with transport | Poor referral system without transport |

| Polite and courteous health workers | Rude health workers |

Factors affecting the quality of services

Several factors were mentioned as affecting the quality of services delivered by health facilities. According to the communities, these were: inadequate numbers of health technical and support staff, shortage of essential drugs, poor attitude of the health workers, high health care costs and long distances to the health facilities. The key informants interviewed mentioned a drastic decline in the quality of services provided by public facilities over the years; this they attributed to lack of qualified staff, rude health workers, inadequate health budgets, inadequate health staff, lack of essential drugs, corruption and broken down health infrastructure. These views were captured in the quotes presented below.

“Yes because if the health workers are enough, they even treat patients faster but what brings a problem is that at times there is one or two yet the patients become so many for them and they can not treat them all fast enough.”

—IDI with a vulnerable member of the community

“To make it worse, even in the health centers which are operational there is a shortage of drugs and at times no drugs at all and in most cases patients are prescribed medicine and told to go and buy from private clinics.”

—Local politician

Respondents were asked to state what, according to them, affected the quality of services. Table 2 summarizes their responses and provides a sense of how strongly felt the issues were.

Table 2.

Factors that affect the quality of services

| Factors | Female FGD’s | Male FGD’s | Health workers | Vulnerable persons | Politicians and opinion leaders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortage of drugs | xx | x | xx | xxx | xxx |

| Poor attitude of health workers | xxx | xxx | x | xx | x |

| Inadequate health workers | x | xxx | xx | xxx | |

| Long waiting time | x | x | xxx | x | |

| Lack of amenities, supplies and equipment | x | xx | xx | xx | |

| Poorly trained staff | x | x | |||

| Long distances to the health facility | x | x | xx | ||

| Poor remuneration of health workers | x | x | x |

Notes: Data sourced from field findings from FGDs and KIs; xxx, Mentioned by many respondents; xx, Mentioned by a fair number of respondents; x, Mentioned by few respondents.

The influence of quality on utilization

Quality was viewed as an important influence on utilization of services. They mentioned that everybody would have liked to seek health care from facilities where there is proper medical treatment, with drugs, and adequate health staff. The narrative below summarizes the community responses about how quality influences the utilization of services.

Long waiting time

It was reported that in some of the health facilities people had to queue for long hours before receiving attention. As a result of this, some community members resort to self-medication or seeking care from drug shops, private clinics, and traditional healers. This is what one of the vulnerable members who was an orphan had to say:

“If the (patients) take long without being given attention it is bad. That is why you find most people running away from such places which make patients to wait for so long like XXX hospital. Most people have resorted to private clinics because in XXX hospital they wait for so long due to the fact that it is a government hospital and people are many.”

—IDI with vulnerable member, Iganga

Poor geographical access to health facilities

It was mentioned that pregnant women seek care from traditional birth attendants (TBAs) because of poor geographical access to health facilities. This at times leads to maternal and neonatal deaths when they get complications and referral for appropriate treatment is delayed. In addition, the poor tend to go to the nearest health facility accessible even if it has poor services, due to lack of transport fare to the health facilities. Unlike the poor, the rich do not mind the distance so long as they can get better quality health care services. The poor commonly walk or use bicycles to carry their sick to hospitals if they have no money to pay the taxi fare.

“It depends on the type of treatment one is seeking. If it is severe illness, then you need to move to far away health facilities to get the right medical treatment.”

—Female, FGD, Iganga

Poor infrastructure and hygiene

Poor infrastructure and hygiene at times discourages the community from seeking care from government facilities. Respondents mentioned that most of the public facilities were constructed in the 1960s to accommodate small populations but these had not been expanded as the population increased.

Lack of equipment and qualified staff

Lack of equipment and qualified staff at health facilities affects the capacity to diagnose and treat patients appropriately. Many health facilities were reported to lack functioning health equipment for theatre and other general operations, as well as qualified staff. This was reported to lead to situations where the community seeks care from facilities that have the above facilities. If the illness is minor they reported that they may go to a PFP facility. If the illness is severe then they may go to a hospital which may be PNFP, private or even public.

Patients reported that they went to government facilities because of access to qualified skilled staff, and free services. They gave examples of a few situations where utilization had increased with provision of equipment. In Kitagata hospital, Bushenyi district, when the X-ray machine was repaired, there was an increase in utilization of services. Similarly, where ambulatory services and a doctor were available at the health center, there was an increase in utilization of services.

Lack of drugs in public facilities

One of the reasons that were given for seeking care in private facilities or seeking no care at all was lack of drugs in the public facilities.

“They only go to drug shops and private clinics due to lack of drugs in government facilities.”

—FGD female Iganga

“People in this area know where to go for health services, but the bad thing is to go there and you don’t find services. No drugs, no laboratory services, so this discourages patients to go there for medical care.”

—FGD male Bushenyi

Interpersonal interactions

Another reason that was given for seeking care with private providers was because they welcome people well and are thus considered friendly to the public.

“They only go to private clinics because private clinic owners are friendly to people and allow payment in small amount instalments until the completion of treatment”

—FGD female Iganga

On the other hand, one of the reasons that was given for not seeking health care in public facilities was the negative attitudes of health workers towards patients. It was recounted in Bushenyi district that poor women who cannot afford soap, clothes, and simple gloves do not seek maternity care as they are despised and sent away by health staff. If one is poor, health workers shout at them and also ignore them by not assisting or passing by without paying attention to them.

Use of facilities that provide perceived quality care

Most of the respondents said the rich are concerned about the quality of health care. People who are rich tend to use private clinics and big private hospitals because of the perceived good quality health care. The poor go to government health centers irrespective of the fact that these public facilities are perceived to provide poor quality services.

“If a poor person has no money he won’t seek quality care. Ideally he would also wish to get quality care, eg, from a private clinic.”

—FGD Bushenyi

“It’s the rich who care about quality, but the poor don’t even know their rights they go for anything.”

—KI Iganga

These influences on utilization and groups most affected are summarized and presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

How quality influences the utilization of health services

| Attribute of quality | Group most affected | Effect on utilization |

|---|---|---|

| Negative attitudes of health workers | The poor, ethnic minorities | They decide not to seek services eg, antenatal and delivery services |

| They don’t receive services such as drugs, proper examination | ||

| They go to traditional providers/herbalists | ||

| Long waiting times | Those seeking care from public facilities especially those from lower social classes | Self medication |

| They go to drug shops, private clinics or traditional healers | ||

| Long distances to health facilities | Pregnant women | Deliver with traditional birth attendants who are located closer to them |

| The poor | Seek care from facilities that are closer irrespective of the quality of care provided | |

| Decide not to seek formal care | ||

| Poor infrastructure and hygiene | Those using public facilities | They go to private providers |

| Lack of equipment for theatre, drugs, and qualified staff | Both the poor and rich | Go to the facilities that have the equipment, drugs depending on severity of the condition. For minor illness private clinics, for severe illnesses government or PNFP hospitals |

| Seek no care | ||

| Self medication | ||

| Good interpersonal relations | Both the poor and rich | Use private facilities |

Abbreviation: PNFP, private not-for-profit.

Aspects of quality to be improved

There are several factors which were perceived to affect the quality of services delivered. The respondents mentioned issues which they felt the government and health workers needed to address in order to improve the quality of services. These areas are summarized below.

Provision of more drugs

Shortage of drugs is one of the main problems reported in the health facilities. The community reported that they would like to see an improvement in this area. According to them, drugs are stolen from public facilities. They suggested that closer monitoring and supervision of the health workers should be done to curb these thefts.

Illegal payment of fees

Another major complaint that the community had was the problem of being asked to pay unofficial fees at the health facilities. They felt that closer supervision and monitoring of health workers could help to reduce this practice.

Absenteeism

Absenteeism of health workers had been noted to be on the increase. This was attributed to poor remuneration of the health workers. It was suggested that their remuneration should be improved so that they can be motivated to work harder.

Rude health workers

It was reported that health workers are often rude to patients, especially the poor. This is another area where the community wanted to see a change. The majority of the respondents said, health service providers should improve their attitude towards clients and provide good quality services.

“Good care from the health workers. We need health workers who can give us attention. Some health workers are so rude. Sometimes women are in labor but they just slap them instead of talking to them.”

—Ki Disabled Iganga

Increased financial resources to the health sector

The health workers interviewed felt that the finances given to the health sector are insufficient. They said that more resources need to be allocated to the health sector so that the sector can employ sufficient staff, provide more drugs, equipment and proper infrastructure.

More health workers

The community noted that the number of health workers is inadequate, therefore government needs to increase the number of health workers.

Hygiene in facilities

Poor hygiene was noted to be a big problem at both public and private facilities. This was an area that they felt needed emphatic effort by everyone. They suggested the use of posters and inspection of health facilities to improve hygiene in the communities and at health facilities. Bye laws and regulations could also be enforced to encourage the health facilities to maintain the set standards.

Discussion

The results of the study show that user perceptions and definitions of the quality of health services depend on a number of factors related to technical competence, accessibility to services, interpersonal relations and presence of adequate drugs, supplies, staff and facility amenities. Quality was categorized according to two options either poor or good. This ranking largely depended on how close the health facilities where, the availability of supplies such as drugs, equipment for diagnosis, presence of qualified health personnel and good interpersonal relationships. More technical definitions of quality focus on eight attributes: technical competence, patient satisfaction, efficiency, effectiveness, access to services, safety of procedures, continuity of care, and facility amenities. Comparing these to the attributes mentioned at community level, the most important dimensions of quality for the clients according to the research were technical competence, interpersonal relations, accessibility, and facility amenities.

For clients and communities, quality care is something that meets their perceived needs. Since a client’s needs often differ, their personal satisfaction ultimately depends on the perception, attitude and expectations of each individual. Ultimately, the dimensions of quality that relate to client satisfaction affect the health and well being of the community since client satisfaction is a strong influencing factor in health seeking behavior.3

Based upon these perceptions, public facilities were judged to be providing poor quality services. The factors that were mentioned as affecting the quality of services delivered by health facilities were inadequate numbers of trained health workers, shortage of essential drugs, poor attitude of the health workers, high health costs, and long distances to health facilities. This scenario is partially explained by the amount of the government budget expenditure on health. Health spending has accounted for just about 7%–9.6% of the Uganda National Budget over the last five years.11 This falls short of the target of 15%, which the Uganda government agreed to spend on health during the Abuja declaration (2000).This spending is estimated to cover just about 1/3 of what the country needs to meet its minimum health care package needs. According to the annual health sector performance report of 2006/2007,12 Uganda spends only US$7.8 per capita on health, down from USD$10 per capita in 2004/5. The public sector needs to spend USD$28 per capita and up to USD$40 when antiretroviral drugs are included.13 The government therefore needs to increase its expenditure on health. However, further reallocation of priorities and increased efficiency in the use of the existing resources within the sector is also warranted.

The quality of services offered by public and selected private facilities has influenced the utilization of health facilities, and it bore close relationship to the health care-seeking behavior of the people. The poor sought care from public facilities while the nonpoor or rich went to private facilities irrespective of cost since they were considered to offer better quality services. This indicated that the poor opted for low cost or no cost health care unlike the nonpoor who could afford costly medical care from well established privately owned facilities. Chuma and colleagues14 in Kenya reported similar findings. Poorer households were more likely to use shops, government dispensaries and herbs, while least poor households used private clinics.

The high use of the private sector has resulted in Uganda having a very high out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure (58%).15 This indicates that the vulnerable are likely to be exposed to catastrophic expenditures and to be pushed into the medical poverty trap. It also indicates that the poor may not be benefiting maximally from the government subsidies in the health sector. Although governments have claimed that they provide services to ensure that the poor are reached, research has shown that their health service subsidies tend to provide considerably greater benefits to the well off.16 Indeed the research demonstrated that when the poor go to public health facilities, they are subjected to long hours of waiting and may not even receive services without providing some under-the-table payments. The health sector needs to focus on establishing objectives whose achievements will necessitate the poor benefiting fully from the services offered.16

The health services delivered in the country are not optimal. Several areas for improvement were suggested such as provision of more drugs, more health workers, and more funding for the health sector. In order to achieve these improvements, financial mechanisms that can provide a larger resource envelope for the health sector are required. Alternative financing mechanisms such as community prepayment schemes and social health insurance hold some promise. The main challenge however lies in empowering the community through employment, income-generating schemes, and microcredit schemes17,14 so that the community is able to contribute towards their health care costs.

The study however had some limitations; these include the fact that it was done in two districts and therefore the results cannot be generalized to the rest of the country. Secondly it presents the perceptions of the community members, and this was not verified with an objective assessment of quality.

Conclusion

The present delivery of health services does not adequately meet the needs of the most poor and vulnerable. Perceptions of being discriminated against or being treated badly because of their socioeconomic status and/or rural residence were found to be common. This paper argues that there should be improvement of quality of health services for everybody and particular attention paid to the poor. Despite wide focus on improvement of the existing infrastructure and donor funding, there is still low satisfaction with health services and poor perceived accessibility. The involvement of the poor and vulnerable will be crucial in providing services that are perceived to be responsive to their special needs.

Emerging issues

There is a need to stimulate awareness of the problems encountered by the poor in seeking health care to policy makers, politicians, civil society, and health officials.

Improvement of quality of health care should not only focus on infrastructure but include provision of essential drugs and adequate numbers of motivated health workers as well.

At current budget levels it will be difficult to improve availability of staff and essential drugs and supplies. The Ugandan Ministry of Health has a challenge to explore and introduce new mechanisms to raise additional resources for health care without increasing the burden on the poor and vulnerable.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the District Health teams of Iganga and Bushenyi district for the support that they gave us during the data collection process. Our thanks also go to all those who played a part in collecting the data. This work is part of formative research for the Future Health Systems Research Programme Consortium which is supported by the UK Department for International Development (DfID). The Consortium is led by the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health (Baltimore, MD, USA), which provides technical support, along with the Institute of Development Studies (IDS, Sussex, UK), to the implementing institutions. These are: Makerere University School of Public Health (Kampala, Uganda), University of Ibadan (Baden, Nigeria), the China Health Economics Institute (Beijing, China), the India Institute of Health Management Research (Japer, India), and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh (Dhaka, Bangladesh). The support and contributions of these institutions is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. GWP is the Ugandan PI for the Future Health Systems study team. GWP, EEK, JK, and OO initiated the concept for the qualitative work. JK did the data analysis and co-wrote drafts of the manuscripts. EEK participated in the analysis reported in this paper and co-wrote drafts of the manuscript. OO contributed to formulation of the study questions and concept and co-wrote the manuscript. MA was responsible for the data collection. HM contributed to the formulation of the study, reviewed and provided substantial inputs into the manuscript. All authors read, provided substantial input, and approved the final manuscript. JK and EEK are guarantors of the paper.

References

- 1.Odaga J. Health inequality in Uganda – the role of financial and non-financial barriers. Health Policy Dev. 2004;2:192–208. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konde LJ, Okuonzi S, et al. The potential of the private sector to improve health outcomes in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Makerere University Institute of Public Health; 2006. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brawley M. The client perspective: What is quality health care service? A literature review. Kampala, Uganda: Delivery of Improved Services for Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donabedian A. The seven pillars of quality. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:1115–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Bank . World development report: Attacking poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.[GOU] Republic of Uganda . Statistical abstract. Kampala, Uganda: U. B. o. Statistics; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- 7.[GOU] Republic of Uganda . Uganda participatory poverty assessment report: learning from the poor. Kampala, Uganda: P. a. E. D. a. O. G. B. Ministry of Finance; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holzmann R, Jorgensen S. Social risk management: A new conceptual framework for social protection and beyond Social protection discussion paper number 0006. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucas H, Bloom G. Protecting the poor against health shocks A working paper. Baltimore MD: Future Health Systems Research Program Consortium; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.[GOU] Republic of Uganda . Social protection in Uganda. Phase 1 report: Vulnerability assessment and review of initiatives. Kampala, Uganda: L. a. S. D. Ministry of Gender; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.[GOU] Republic of Uganda . Annual Health Sector Performance report. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uganda Ministry of Health . Annual Health Sector Performance Report Financial Year 2006/2007. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health; 38. [Google Scholar]

- 13.[GOU] Republic of Uganda . Annual health sector performance report. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuma J, Gilson L, Molyneux C. Treatment-seeking behaviour, cost burdens and coping strategies among rural and urban households in Coastal Kenya: an equity analysis. Trop Medicine Int Health. 2006;12:673–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Bank . Improving health outcomes for the poor in Uganda: Current status and implications for health sector development African Region Human Development Working Paper Series. Kampala, Uganda: World Bank; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwatkin DR, Bhuiya A, Victoria PG. Making health systems more equitable. Lancet. 2004;364:1273–1280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onwujekwe O. Inequities in health care seeking in the treatment of communicable endemic disease in South East Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]