Abstract

The small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) are biologically active components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), consisting of a protein core with leucine rich-repeat (LRR) motifs covalently linked to glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains. The diversity in composition resulting from the various combinations of protein cores substituted with one or more GAG chains along with their pericellular localization enables SLRPs to interact with a host of different cell surface receptors, cytokines, growth factors, and other ECM components, leading to modulation of cellular functions. SLRPs are capable of binding to: (i) different types of collagens, thereby regulating fibril assembly, organization, and degradation; (ii) Toll-like receptors (TLRs), complement C1q, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), regulating innate immunity and inflammation; (iii) epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R), insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR), and c-Met, influencing cellular proliferation, survival, adhesion, migration, tumor growth and metastasis as well as synthesis of other ECM components; (iv) low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP-1) and TGF-β, modulating cytokine activity and fibrogenesis; and (v) growth factors such as bone morphogenic protein (BMP-4) and Wnt-I-induced secreted protein-1 (WISP-1), controlling cell proliferation and differentiation. Thus, the ability of SLRPs, as ECM components, to directly or indirectly regulate cell-matrix crosstalk, resulting in the modulation of various biological processes, aptly qualifies these compounds as matricellular proteins.

Keywords: Biglycan, Decorin, Lumican, Inflammation, Fibrosis, Innate immunity

Introduction

Small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) are biologically active components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and are structurally characterized by a central protein core made up of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) flanked by cysteine-clusters and substituted with covalently linked glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains (Huxley-Jones et al. 2007, Iozzo 1998; McEwan et al. 2006; Schaefer and Iozzo 2008). After synthesis, these proteoglycans are secreted into the pericellular space and abound in the majority of tissues. They are divided into five distinct classes, based on N-terminal Cys-rich clusters of the protein core and ear repeats (C-terminal repeats specific to SLRPs) (McEwan et al. 2006), chromosomal organization and homologies at the protein and genomic levels (Table 1; (Schaefer and Iozzo 2008). The GAG chains of SLRPs are sulphated, linear disaccharide repeating units made from acetylated amino sugar moieties and uronic acid, forming negatively charged chondroitin sulphate (CS) or dermatan sulphate (DS) chains. They are covalently linked to the respective protein core via serine residues (Gandhi and Mancera 2008; Iozzo 1998). By contrast, the keratan sulphate (KS) GAGs are composed of repeating disaccharide units containing galactose (-4N-acetyl-glucosamine-β1,3-galactose-β1). Decorin, biglycan (CS/DS class I proteoglycans) and lumican (KS class II proteoglycan) are the best characterized members of the SLRP family.

Table 1.

Classification of SLRPs1

| Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Class V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biglycan | Fibromodulin | Epiphycan | Chondroadherin | Podocan |

| Decorin | Lumican | Opticin | Nyctalopin | Podocan like protein-1 |

| Asporin | PRELP | Osteoglycan | Tsukushi | |

| ECM2 | Keratocan | |||

| ECMX | Osteoadherin |

1based on several parameters including conservation and homology at the protein and genomic level, the presence of characteristic N-terminal Cys-rich clusters with defined spacing, and chromosomal organization (Schaefer and Iozzo 2008)

SLRPs consist of two different structural components, namely a conserved protein core involved in protein/protein interactions (Hocking et al. 1998; Iozzo 1997; Kresse et al. 1993) and varying numbers and types of GAG chains in a single molecule. Along with their pericellular localization, this allows SLRPs to interact with different molecules and cell-surface receptors, thereby modulating a wide range of cell-matrix interactions (Brandan et al. 2008; Iozzo 1998; Perrimon and Bernfield 2001; Roughley 2006; Schaefer and Iozzo 2008). These functions were mostly elucidated by the characterization of specific SLRP-deficient mice (Ameye et al. 2002; Chakravarti et al. 1998; Chen et al. 2002; Corsi et al. 2002; Danielson et al. 1997; Heegaard et al. 2007; Svensson et al. 1999; Xu et al. 1998; Young et al. 2002) and are briefly summarized in Table 2. SLRPs were long known to be able to bind to various types of collagens thereby regulating the kinetics, assembly, and special organization of fibrils in skin, tendons, and cornea (Iozzo 1999; Kalamajski and Oldberg 2009; Kresse et al. 1997; Neame et al. 2000; Reinboth et al. 2006; Schonherr et al. 1995b; Svensson et al. 1995; Wiberg et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2006). In the clinical setting, protein core fragments serve as biological markers for various degenerative cartilage disorders (Melrose et al. 2008).

Table 2.

Characteristics of SLRP-deficient mice

| Gene disrupted | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Biglycan | Reduced bone mass with decreased production of bone marrow stromal cells and larger irregular collagen fibrils indicating an osteoporosis-like phenotype; Spontaneous aortic dissection and rupture | (Chen et al. 2002; Heegaard et al. 2007; Xu et al. 1998) |

| Decorin | Skin fragility phenotype with loosely packed collagen networks resembling Ehlers-Danlos syndrome; Intestinal tumor formation | (Bi et al. 2008; Corsi et al. 2002; Danielson et al. 1997) |

| Lumican | Skin laxicity and corneal opacity | (Chakravarti et al. 1998) |

| Fibromodulin | Abnormal collagen fibrillogenesis in tendons | (Svensson et al. 1999) |

| Biglycan and Decorin | Severe osteopenia and increased skin fragility | (Young et al. 2002) |

| Biglycan and Fibromodulin | Severely altered collagen fibril assembly with ectopic ossification of tendons and premature arthritis | (Ameye et al. 2002) |

However, the biological functions of SLRPs extend far beyond their interactions with collagens. SLRPs interact with various cytokines, including transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), bone morphogenic protein (BMP-4), Wnt-I-induced secreted protein-I (WISP-1), von Willebrand factor (VWF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) (Bi et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2004; Desnoyers et al. 2001; Guidetti et al. 2004; Inkson et al. 2009; Kolb et al. 2001; Kresse and Schonherr 2001; Nili et al. 2003; Tufvesson and Westergren-Thorsson 2002), leading to modulation of their diverse biological functions. Pharmacologic manipulations of these interactions could potentially be exploited for the treatment of proliferative, inflammatory, and fibrotic disorders (Goldoni and Iozzo 2008; Schaefer and Iozzo 2008; Schaefer et al. 2002; Schaefer et al. 2004). As extracellular compounds SLRPs engage various signaling receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Schaefer et al. 2005), insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) (Schaefer et al. 2007), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) (Iozzo et al. 1999), low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP-1) (Brandan et al. 2006), integrin α2β1 (Fiedler et al. 2008; Guidetti et al. 2002), and c-Met (Goldoni et al. 2009), thereby acting as direct triggers of signal transduction. These interactions result in modulation of cellular growth, proliferation, differentiation, survival, adhesion and migration under developmental, physiological and pathological conditions (Brandan et al. 2008; Schaefer and Iozzo 2008; Zoeller et al. 2009). For further details regarding the interaction of SLRPs with cell membrane receptors we refer to more extensive reviews (Brandan et al. 2008; Goldoni and Iozzo 2008; Schaefer and Iozzo 2008; Schaefer and Schaefer 2009).

Thus, SLRPs aptly fit the definition of matricellular proteins due to their: (i) extracellular location, (ii) modulatory effects on synthesis, assembly and degradation of fibrils without being part of the fibrillar structure itself, and (iii) direct (receptor-mediated) and indirect (via interaction with cytokines, growth factors and other ECM components) regulation of cell-matrix crosstalk, influencing a host of biological processes (e. g. inflammation, fibrosis, tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, coagulation and wound healing). In the present review, we focus primarily on the matricellular functions of decorin, biglycan (class I proteoglycans), and lumican (class II proteoglycan), which are briefly summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Matricellular functions modulated by the SLRPs decorin, biglycan and lumican

| Biological function modulated | Mechanism mediated / involved in modulation |

|---|---|

| Receptor-binding associated with signal transduction | EGF-R1(D ), IGF-IR(D), LRP-1(D), c-Met(D), TLR2(B), TLR4(B) and CD14(L) |

| Modulation of cytokine bio-activity | BMP-4(B), PDGF(D,B), TGF-β(D,B), TNFα(D,B), VWF(D) and WISP-1(D,B) |

| Fibrillogenesis, fibrillar organization and degradation | Bind collagens(D,B,L) and elastic fibril components(D,B) regulating fibrillar kinetics(D), assembly(D,L) and degradation(D,L), thereby modulating the structure, stability and integrity of the ECM. |

| Adhesion and migration | By binding to adhesion(D) and anti-adhesion molecules(D) and also by signaling via IGF-IR(D), integrin α2β1(D,L), RhoA(D,B), Rac1(D,B), Syk(D) and Erk1/2(L), inhibits or enhances adhesion and migration in a cell type specific manner. |

| Cellular proliferation | By binding and modulating receptor mediate signaling (EGFR, ErbB4 and VEGF-R2)(D); by modulating: (i) growth factor bioactivity (TGF-β(D) and PDGF-BB(B)); (ii) cell cycle (influencing expression of p21(D,L), p27(D,B), cdk2(B) and cyclin D1(L)) and (iii) the myostatin pathway, regulate cellular growth in a cell and stage-specific manner(D). |

| Cellular survival | Regulate cellular survival by modulating IGF-IR signaling(D), EGFR(D), caspase-3 activity(D,B) and Fas/FasL-mediated apoptotic pathway(L). |

| Inflammation and innate immunity | Acts as PAMP(B) or presents PAMPs(L) to the receptor thereby triggering or enhancing the inflammatory response. Also sustains inflammation by regulating chemokine gradient(D,B,L) and complement activity(D,B). |

| Fibrosis | Potent antifibrotic agent(D), influencing fibrogenesis in different organs by a number of distinct mechanisms: (i) inhibition of TGF-β, (ii) regulation of ECM synthesis and turnover and by (iii) regulating cell death, adhesion and migration. |

1The SLRP modulating the respective matricellular function is indicated as subscript and abbreviated as follows: D, decorin; B, biglycan; L, lumican

SLRPs as modulators of fibrillogenesis, fibrillar organization and degradation

By their ability to bind to different types of collagens and elastic fibril components, SLRPs impact on extracellular matrix organization, modulating the structural and functional environment of cells. The interaction of SLRPs with collagens has been shown to enhance fibril stability (Keene et al. 2000; Neame et al. 2000) and to protect fibrils from proteolytic cleavage by various collagenases (Geng et al. 2006).

In vivo, the role of decorin in regulating collagen fibrillogenesis was elucidated by studies using knockout mice, which exhibit loosely packed collagen fiber networks with increased fibril diameter, leading to a skin fragility phenotype (Danielson et al. 1997; Reed and Iozzo 2002). The functional importance of decorin in regulating collagen fibrillogenesis was further emphasized by the altered mechanical function of lung tissue in decorin-deficient mice (Fust et al. 2005). Decorin is involved in lateral growth of collagen fibrils and regulates fibril diameter in vitro (Danielson et al. 1997). It binds to collagen type I, II, III, IV, VI, and XIV (Bidanset et al. 1992; Ehnis et al. 1997; Reed and Iozzo 2002) and has been localized to the ‘d’ and ‘e’ bands of tendon collagen in the “gap zone” (Pringle and Dodd 1990; Weber et al. 1996). Decorin is also involved in lateral fusion of collagen I fibrils by binding to the C-terminus via LRR4-6 of the protein core through protein/protein interactions, which involves more than one binding domain (Keene et al. 2000; Kresse et al. 1997; Reed and Iozzo 2002; Schonherr et al. 1995a; Svensson et al. 1995). The GAG chain of decorin binds tenascin-X and mediates its interaction with collagen fibrils, thereby contributing to extracellular matrix integrity (Elefteriou et al. 2001). Furthermore, the GAG chains are involved in the maintenance of interfibrillar spacing, which also effects fibril diameter (Iozzo 1999; Raspanti et al. 2008; Ruhland et al. 2007).

Biglycan-deficient mice do not suffer from increased skin fragility, but exhibit larger and irregular fibrils leading to thin dermis and reduced bone mass (Corsi et al. 2002; Xu et al. 1998). In vitro, biglycan binds to collagen type I, II, and III but unlike decorin its interaction with collagen does not appear to influence fibril diameter or fibrillar kinetics. However, due to its trivalency biglycan could have a special organizing function on assembly of the extracellular matrix (Douglas et al. 2006; Schonherr et al. 1995b). This notion is supported by the binding of biglycan to the N-terminal ends of the collagen VI tetramers. This leads to supramolecular organization of collagen into hexagonal networks, with biglycan being localized at the intra-network junctions of the collagen VI filaments (Wiberg et al. 2002). Intact biglycan with GAG chains is required for complex formation and interaction with the TGF-β-inducible gene-h3 (beta ig-h3) and collagen VI (Reinboth et al. 2006). The influence of biglycan on collagen fibrillogenesis is further demonstrated by the presence of high amounts of biglycan in keloids (Hunzelmann et al. 1996) and by its localization in the decidualized regions of the endometrium, regulating fibril thickness in the murine decidua (San Martin and Zorn 2003). Decorin and biglycan also regulate collagen fibril assembly coordinately in the cornea (Zhang et al. 2009) and in tendons (Zhang et al. 2006).

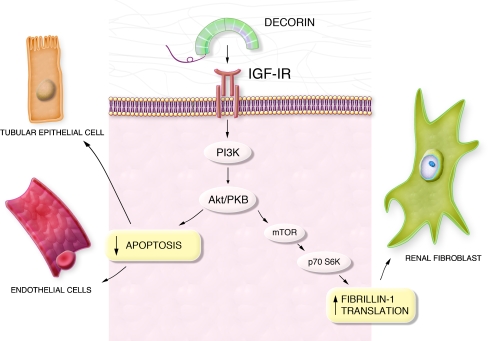

There is some evidence that both SLRPs may also be involved in elastic fiber biology. Decorin forms complexes with fibrillin-1, tropoelastin (the soluble precursor of mature elastin) and microfibril-associated glycoprotein 1 (MAPG-1) (Kielty et al. 1996; Trask et al. 2000). Biglycan is able to bind to the latter two components (Reinboth et al. 2002). Therefore, both proteoglycans were classified as microfibril- and elastic fiber-associated molecules (Kielty et al. 2002). Biglycan regulates elastogenesis as shown by the ability of its GAG chains to inhibit elastin synthesis and assembly in the vessel wall (Hwang et al. 2008). Recent studies have established a molecular link between decorin and the IGF-IR signaling pathway and the synthesis of fibrillin-1 in renal fibroblasts. Translational regulation of fibrillin-1 involves the IGF-IR and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and p70 S6 kinase as downstream targets (Fig. 1) (Schaefer et al. 2007). This intriguing finding indicates that the ECM component decorin is capable of directly regulating the synthesis of another matrix constituent (fibrillin-1). This together with the ability of decorin to regulate the activity of MMPs (Schonherr et al. 2001), underlines the complexity of ECM synthesis and turnover under physiological and pathological conditions.

Fig. 1.

Cell type-specific functions mediated by decorin via modulation of IGF-IR signaling. Decorin binds and induces phosphorylation of the insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) receptor, causing downstream activation of phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) and the Akt/protein kinase B (Akt/PKB) pathway. In endothelial and renal tubular epithelial cells this signaling cascade leads to an inhibition of apoptosis, whereas in renal fibroblasts signaling through mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and p70S6 Kinase (p70S6K) leads to increased translation and synthesis of fibrillin-1. These pathways demonstrate the intricate regulatory mechanisms whereby decorin modulates IGF-IR signaling in a cell type-specific manner, thereby giving rise to different biological outcomes

Lumican-deficient mice suffer from increased skin fragility and corneal opacities due to abnormal fibril assembly and altered interfibrillar spacing, indicating a role in lateral fusion of collagen fibrils (Chakravarti et al. 1998). Besides maintaining normal fibril architecture of the cornea by regulating fibril assembly in the posterior stroma, lumican provides an optimal KS content required for corneal transparency (Chakravarti et al. 2000). In tendons, lumican regulates the assembly of fibrils at an early stage of collagen fibrillogenesis (Ezura et al. 2000). Recently, the binding site of the lumican protein core to collagen type I via Asp-213 of LRR7 has been reported (Kalamajski and Oldberg, 2009).

Fibromodulin, another class II keratan sulphate SLRP binds to collagen and also regulates fibrillogenesis. Its deficiency leads to an abnormal tendon phenotype with impaired collagen fibrils (Svensson et al. 1999; Viola et al. 2007). During tendon development, fibromodulin is involved in collagen fibrillogenesis, regulating fibril assembly and maturation (Ezura et al. 2000). The interaction of fibromodulin with collagen requires more than one binding domain, similar to class I SLRPs. One of these domains appears to be the C-terminal end of the molecule containing the disulfide loop (Font et al. 1998), and the binding to collagen I involves LRR5-7 of the protein core (Kalamajski and Oldberg 2009).

Cellular proliferation

The multitude of matricellular functions performed by SLRPs is further evidenced by their ability to regulate cellular proliferation. Decorin has long been known to regulate cellular growth, as ectopic overexpression of decorin retarded cell growth (Yamaguchi and Ruoslahti 1988). Diverse mechanisms of growth regulation by decorin have been revealed over the years and these were attributed to its ability to, (i) engage receptors modulating signaling pathways, (ii) act as a growth factor, and (iii) influence regulation at certain cell cycle checkpoints. Decorin inhibits cellular proliferation in a TGF-β-dependent manner in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (Yamaguchi et al. 1990), arterial smooth muscle cells (Fischer et al. 2001), human hepatic stellate cells (Shi et al. 2006), and fibroblasts (Zhang et al. 2007). However, the majority of data concerning decorin-mediated regulation of proliferation was generated in carcinoma cell lines. In tumor cells, decorin binds EGFR and ErbB4, leading to activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, Ca2+ influx, induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21 with subsequent downregulation of the receptor (Csordas et al. 2000; De Luca et al. 1996; Iozzo et al. 1999; Moscatello et al. 1998;; Santra et al. 2002). Decorin-bound EGFR is further internalized and degraded (Zhu et al. 2005). Thus, these extensive studies provide a molecular explanation for the antiproliferative and antioncogenic effects of decorin (Reed et al. 2002; Seidler et al. 2006). Moreover, there is a direct link between decorin deficiency and spontaneous tumor formation (Bi et al. 2008). For further details more extensive reviews are suggested (Goldoni and Iozzo 2008; Nikitovic et al. 2008a). Recently, decorin has been shown to inhibit proliferation of trophoblasts through the EGFR and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGF-R2) signaling pathways (Iacob et al. 2008), indicating that these mechanisms are not restricted to regulation of carcinoma cell proliferation. Interestingly, by binding myostatin and modulating its down-stream signals, decorin can rescue the inhibitory effects of myostatin on myoblast proliferation, thereby acting indirectly as a promoter of cell proliferation (Brandan et al. 2008; Miura et al. 2006).

The role of biglycan in regulating cellular proliferation was addressed only by a limited number of studies. Antiproliferative effects of biglycan were observed in mesangial cells of the kidney, where it inhibited PDGF-BB-induced proliferation (Schaefer et al. 2003) and in bone marrow stromal cells, where WISP-1 blocked the antiproliferative effects of biglycan (Inkson et al. 2009). In pancreatic cancer cells, biglycan induced G1 arrest, thereby inhibiting tumor cell proliferation. This effect was associated with upregulation of the CDK inhibitor p27 and downregulation of cyclin A and proliferating cell nuclear antigen, along with decreased activation of Ras and Erk (Weber et al. 2001). However, in vascular smooth muscle cells biglycan has been shown to favor proliferation in a CDK2- and p27-dependent manner (Shimizu-Hirota et al. 2004). Moreover, the proliferative phase of osteoblast development was associated with increased expression of biglycan, indirectly indicating that biglycan might promote proliferation (Waddington et al. 2003). Based on these data, it is tempting to speculate that similar to decorin, biglycan might regulate proliferation in a cell type-specific manner, either directly via a specific receptor or by contributing to the crosstalk between signaling pathways, or by an indirect mechanism. To interpret these data in more detail, studies on biglycan-mediated signaling are warranted. Up to now, the Toll-like receptors-2 and -4 have been identified as signaling receptors for biglycan (Schaefer et al. 2005), whereas unlike decorin it was found not to signal through the EGFR (Moscatello et al. 1998).

Similar to decorin, lumican also acts as a negative regulator of cellular proliferation, by upregulating the expression of the CDK inhibitor p21 (Li et al. 2004), but it appears that the underlying mechanisms are different. Lumican inhibits proliferation of mouse embryonic fibroblasts by upregulating p21 in a p53-dependent mechanism with decreased cyclin A, D1 and E (Vij et al. 2004). Lack of lumican has been shown to promote proliferation of stromal keratinocytes and embryonic fibroblasts (Vij et al. 2005). Its inhibitory effects on growth are extended to tumor cells, with some of these cells secreting lumican in an autocrine manner (Sifaki et al. 2006). Lumican regulates vertical growth and inhibits anchorage-independent proliferation and cyclin D1 expression in melanoma cells (Brezillon et al. 2007; Vuillermoz et al. 2004). Further details concerning the role of lumican in controlling tumor growth are included in recent reviews (Goldoni and Iozzo 2008; Naito 2005; Nikitovic et al. 2008b).

Programmed cell death

SLRPs act as modulators of programmed cell death. Decorin prevents apoptosis in tubular epithelial cells (Schaefer et al. 2002), endothelial cells, and bone marrow stromal cells (Bi et al. 2005). In tubular epithelial and endothelial cells, the anti-apoptotic effects of decorin are mediated by binding to the IGF-IR and signaling via the PI3K/Akt pathway, which also plays a role in fibrosis (details are described in the section “Fibrosis” below) and angiogenesis (Fig. 1) (Schaefer et al. 2007; Schonherr et al. 2005; Schonherr et al. 2004). It appears that signaling through the canonical IGF pathway may represent a common mechanism by which decorin protects non-carcinoma cells from programmed cell death.

Conversely, in carcinoma cells decorin has been shown to enhance apoptosis via the EGFR and enhanced caspase-3 activity, indicating an additional mechanism, which might explain the anti-oncogenic effects of decorin (Seidler et al. 2006; Tralhao et al. 2003). The role of biglycan and lumican in the regulation of cell survival has not been studied in detail. Biglycan has been shown to protect mesangial cells from apoptosis by decreasing caspase-3 activity (Schaefer et al. 2003). By contrast, lumican mediates Fas-FasL-induced apoptosis by inducing Fas (CD95) in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Vij et al. 2004). The ability of lumican to induce apoptosis has also been reported in tumor cells and could be used to control tumor progression (Vuillermoz et al. 2004).

Interactions with cytokines and growth factors

Decorin, biglycan, asporin, and fibromodulin bind the profibrotic cytokine TGF-β (Hildebrand et al. 1994; Nakajima et al. 2007). However, since TGF-β interacts with conserved leucine-rich repeat structures (Schonherr et al. 1998), it is likely that other SLRPs are also able to form complexes with this cytokine. A lot of attention has been focused on the interaction of decorin with TGF-β, as it had been demonstrated unequivocally that decorin treatment exerts beneficial effects in fibrotic disorders involving TGF-β overproduction in the kidney and other organs (Border et al. 1992; Kolb et al. 2001). Besides inhibition of TGF-β-mediated fibrosis, the binding of decorin to TGF-β has significant biological implications in regulating a number of cellular processes, e. g. (i) modulation of cell proliferation (Li et al. 2008; Yamaguchi et al. 1990), (ii) inhibition of repressive effects of TGF-β on macrophages leading to their activation (Comalada et al. 2003), and (iii) suppression of TGF-β-dependent apoptosis in bone marrow stromal cells (Bi et al. 2005). Several mechanisms for the decorin-mediated inactivation of TGF-β have been postulated, e. g. (i) interaction with TGF-β signaling, either directly or indirectly by regulating modulators of the TGF-β pathway (e. g. fibrillin-1, myostatin) (Abdel-Wahab et al. 2002; Brandan et al. 2008; Schaefer et al. 2007; Yamaguchi et al. 1990; Zhu et al. 2007), (ii) formation of decorin/TGF-β complexes, which are either eliminated from the tissue (via the circulation or by urinary excretion) or in the presence of collagen I are sequestered in the ECM (Schaefer et al. 2001). Conversely, the interaction of decorin with TGF-β could also enhance the bioactivity of TGF-β, as seen in the process of bone formation during remodeling (Takeuchi et al. 1994). The mechanism of interaction of decorin with TGF-β has been described at length in earlier reviews (Iozzo, 1998; Kresse and Schonherr 2001).

Besides its interaction with the IGF-IR, decorin can also bind IGF-I but with a 1000-fold lower affinity than the classical IGF-I-binding proteins, indicating that decorin is more likely to compete with IGF-I for binding to the IGF-IR, rather than with the binding proteins which have KD values in the range of 10-10 M. This suggests that only in situations where decorin is expressed abundantly relevant competition with the classical binding proteins might occur (Schonherr et al. 2005). Decorin binds PDGF, inhibiting downstream phosphorylation of the PDGFR and signaling in aortic smooth muscle cells. These effects could be exploited therapeutically to prevent intimal hyperplasia (Nili et al. 2003). Through its GAG chains, decorin interacts with the von Willebrand factor and is involved in the modulation of ECM organization (Guidetti et al. 2004). Decorin and biglycan also bind and immobilize the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα (Tufvesson and Westergren-Thorsson 2002). Both SLRPs interact with WISP-I, regulating its function in fibroblasts and osteogenic cells (Desnoyers et al. 2001; Inkson et al. 2009). Biglycan also modulates the activity of BMP-4 on osteoblast differentiation (Chen et al. 2004). Furthermore, biglycan and fibromodulin were found to modulate bone morphogenic protein signaling, affecting differentiation of tendon stem progenitor cells, thereby influencing tendon formation (Bi et al. 2007).

The SLRPs have been shown to regulate embryonic development by modulating the activity of various growth factors. Biglycan forms complexes with BMP-4 enhancing its binding to chordin, which leads to its inactivation by the chordin-Tsg (Twisted gastrulation) complex (Moreno et al. 2005). Tsukushi, another member of the SLRP family, acts as a modulator of cellular functions by regulating BMP-4, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and Xenopus nodal-related protein-2 (Xnr2) signaling (Kuriyama et al. 2006; Morris et al. 2007; Ohta et al. 2006). The binding and regulation of asporin to growth factors and its modulatory effects have been considered in a recent review (Ikegawa 2008). By their ability to interact with different growth factors, the SLRPs exhibit regulatory effects on various cellular processes, including development.

Inflammation and innate immunity

There is growing evidence for a significant role of SLRPs as direct and indirect endogenous modulators of inflammation and innate immunity (Al Haj Zen et al. 2006; Schaefer et al. 2002, 2005; Vij et al. 2005). Biglycan, besides being sequestered in the ECM, can also exist as a soluble molecule, e.g. when it is released from the ECM by proteolytic digestion of injured tissues or secreted by activated macrophages (for schematic drawing please see Schaefer and Schaefer 2009). Similar to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), soluble biglycan acts as an endogenous ligand of TLR4 and TLR2 in macrophages. These interactions lead to activation and downstream signaling, via p38, p42/44, and NFκB in a MyD88-dependent manner and subsequent synthesis and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Schaefer et al. 2005). Both the protein core and the GAG chains of biglycan are required for activation of these pathways. Generation of TNFα and MIP2 enhances recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils, which in turn secrete additional biglycan, thereby creating a positive feedback loop that stimulates autocrine and paracrine inflammatory responses. The clinical significance of this has been shown by a survival benefit of biglycan-null mice in TLR4- (gram-negative) or TLR2-dependent (gram-positive) sepsis. Improved survival in this model was associated with lower plasma levels of TNFα and reduced infiltration of mononuclear cells into the lung, a major target organ of sepsis in mice (Schaefer et al. 2005). In a model of non-infectious inflammatory renal injury, overexpression of biglycan in the kidney was associated with increased numbers of infiltrating mononuclear cells (Babelova et al. 2009; Schaefer et al. 2002). What is more, soluble biglycan activates the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome by inducing caspase-1 and releasing mature IL-1β without further need for additional costimulatory factors. In terms of receptors involved, biglycan interacts with TLR2/4 and purinergic P2X4/P2X7 receptors, thereby inducing receptor cooperativity (Babelova et al. 2009). In addition, formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) appears also to be involved in biglycan-mediated activation of the inflammasome (Babelova et al. 2009). Under pathological conditions, in a model of inflammatory renal injury (unilateral ureteral obstruction) and in LPS-induced sepsis, biglycan deficiency was associated with lower levels of active caspase-1 and mature IL-1β in kidneys, lungs and in the circulation (Babelova et al. 2009). It is tempting to speculate that biglycan upon its release from the ECM acts as an autonomous trigger of the inflammatory response reaction. On the other hand, in pathogen-driven inflammation biglycan might potentiate PAMP-triggered inflammation by engaging a second TLR that is not involved in pathogen-sensing.

Indirectly, SLRPs may modulate the innate immune response at various levels. SLRPs can influence TLR signaling by presenting PAMPs to the receptor complex. This is evident in the ability of lumican core protein to bind and present lipopolysaccharide to CD14, thereby activating the TLR4 pathway (Wu et al. 2007). In addition, SLRPs enhance the activation of the immune system by their ability to modulate the activity of TGF-β, a potent immunosuppressive cytokine (Wojtowicz-Praga 2003). Similar to biglycan, decorin is also capable of modulating inflammation by various mechanisms, especially by its effects on macrophages. It binds TGF-β and reverses its repressive effect on macrophages. Furthermore, it inhibits macrophage proliferation and apoptosis and enhances the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Comalada et al. 2003). The anti-proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects of decorin on macrophages are mediated by inducing the inhibitors of the CDKs p27(Kip1) and p21(Waf1), which are important for cell cycle regulation. What is more, decorin also inhibits the effects of the macrophage colony stimulating factor (Xaus et al. 2001).

The SLRPs are also involved in the recruitment of immune cells to the site of injury, either directly by acting as ligands to cell surface receptors or indirectly by different mechanisms. Decorin stimulates the production of MCP-1, a mononuclear cell-recruiting chemokine, thereby sustaining the inflammatory state (Koninger et al. 2006). Biglycan, besides its interaction with TLRs (Schaefer et al. 2005), acts as a ligand for selectin L/CD44 and is directly involved in the recruitment of CD16(-) natural killer cells (Kitaya and Yasuo 2009). Lumican, by binding and signaling via FasL, enhances the synthesis and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and the recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils (Funderburgh et al. 1997; Vij et al. 2005). The core protein of lumican binds the CXC-chemokine KC (CXCL1), establishing a chemokine gradient that regulates neutrophil infiltration (Carlson et al. 2007). Furthermore, decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin, osteoadherin and chondroadherin bind C1q, resulting in the case of fibromodulin, osteoadherin, and chondroadherin in activation of the classical complement pathway, and leading to an enhanced inflammatory response (Sjoberg et al. 2009).

Thus, SLRPs by: (i) acting as PAMP analogues, (ii) aiding the presentation of PAMPs to the receptor complex, or (iii) interacting with various cytokines, chemokines and complement factors, modulate inflammation and innate immunity by a host of mechanisms, both in non-infectious and in pathogen-mediated inflammatory conditions.

Fibrosis

Taking into account all matricellular functions of SLRPs mentioned above, including the regulation of cell behavior, the synthesis and degradation of the ECM, the activity of profibrotic factors, and the recruitment of infiltrating cells, SLRPs are undoubtedly important players in fibrogenesis. While fibrosis occurs in diverse organs, its pathological hallmarks are quite comparable, irrespective of the tissue affected. These include: (i) enhanced and aberrant activation of profibrotic growth factors (e. g. TGF-β); (ii) accumulation of activated (myo)fibroblasts; (iii) altered composition and increased deposition of ECM; and (iv) persistent inflammation, which perpetuates fibrotic transformation (Hewitson 2009). Among various SLRPs, a lot of attention has been focused on the antifibrotic effects of decorin as a neutralizing factor of TGF-β (Border et al. 1992; Yamaguchi and Ruoslahti 1988). In several models of fibrosis it was shown that treatment with decorin considerably attenuated fibrogenesis, regardless of tissue and mode of decorin administration (Al Haj Zen et al. 2006, Border et al. 1992; Fukui et al. 2001; Grisanti et al. 2005; Huijun et al. 2005; Isaka et al. 1996; Kolb et al. 2001; Krishna et al. 2006). Two decades of investigations, after the initial observation by Border et al. (1992) confirmed the antifibrotic effects of decorin in a host of organs, such as the kidney (Schaefer et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2007), lung (Kolb et al. 2001), heart (Weis et al. 2005), skeletal muscle (Brandan et al. 2008), liver (Shi et al. 2006), blood vessels (Al Haj Zen et al. 2006), skin (Krishna et al. 2006), and conjunctiva (Grisanti et al. 2005). Furthermore, our understanding of the underlying mechanisms have improved considerably. There is now good evidence that decorin involves multiple signaling pathways by its interactions with the IGF-IR, EGFR, LRP-1 and c-Met (Goldoni et al. 2009; Schaefer and Iozzo 2008). Thus, it appears that it is not the direct physical interaction of decorin with TGF-β (Hildebrand et al. 1994; Schonherr et al. 1998) but rather its interference with the TGF-β signaling cascade (described in the section “Interactions with cytokines and growth factors”, above) that plays a key role in the neutralization of this cytokine. Furthermore, the binding of decorin to TGF-β and collagen I has been shown to be important for sequestration of the cytokine in the ECM (Markmann et al. 2000; Schaefer et al. 2001). Interestingly, even by triggering the same pathway decorin may give rise to distinct biological outcomes (Fig. 1), depending on the cell type and biological context. In this light, previous observations regarding the consequences of decorin/TGF-β interactions, implicating inactivation (Border et al. 1992), activation (Takeuchi et al. 1994) or lack of effects on TGF-β activity (Hausser et al. 1994), do not appear irreconcilable any longer.

The antifibrotic effects of decorin are not only limited to its interaction with TGF-β but involve other mechanisms as well (Schaefer et al. 2002). Decorin deficiency (Danielson et al. 1997) aggravated renal fibrosis significantly in unilateral ureteral obstruction or diabetic nephropathy due to enhanced apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells (Schaefer et al. 2002). Acceleration of apoptosis was independent of TGF-β and was based on direct interaction of decorin with the IGF-IR in tubular epithelial cells, followed by phosphorylation of the receptor and activation of Akt/PKB (Fig. 1) (Merline et al. 2009; Schaefer et al. 2002; Schaefer et al. 2007; Schonherr et al. 2005). Furthermore: (i) collagen I deposition was diminished in fibrotic decorin-null kidneys even though synthesis was enhanced, suggesting that decorin may protect collagen fibrils from proteolytic digestion (Geng et al. 2006; Schaefer et al. 2002); (ii) TGF-β activity was enhanced, underlining the importance of decorin in TGF-β inactivation; and (iii) proinflammatory biglycan was upregulated, resulting in enhanced infiltration of mononuclear cells. In the heart, the absence of decorin resulted in abnormal scar formation after myocardial infarction (Weis et al. 2005).

The ability of decorin to regulate adhesion and migration in a cell-dependent manner further underlines its complex role in fibrogenesis. In fibroblasts deficient in decorin, increased cell spreading was reported (Gu and Wada 1996), while exogenous addition of decorin inhibited fibroblast adhesion to a variety of substrates, indicating the anti-adhesive effects of decorin (Gu and Wada 1996; Winnemoller et al. 1991; Winnemoller et al. 1992). Conversely, by binding and signaling via the IGF-IR and integrin α2β1, decorin promotes endothelial cell adhesion and migration on collagen type I (Fiedler et al. 2008). In fibroblasts, the core protein of decorin induced increased synthesis and activation of RhoA and Rac1 and has been shown to remodel lung fibroblasts enhancing their migration by inducing morphological and cytoskeletal changes (Tufvesson and Westergren-Thorsson 2003). Thus, decorin appears to be a potent antifibrotic molecule, influencing fibrogenesis in different organs by a number of distinct mechanisms, i.e. by inhibition of TGF-β, regulation of ECM synthesis and turnover, modulation of cell death, and adhesion and migration).

The role of biglycan in fibrogenesis is not well understood. No beneficial effects were seen in pulmonary fibrosis when biglycan instead of decorin was adenovirally induced (Kolb et al. 2001). This is conceivable, taking into account that the proinflammatory effects of biglycan are mediated via TLR2/4 (described in the section “Inflammation and innate immunity”). Recently, biglycan has been shown to be protective in cardiac fibrosis following myocardial infarction, based on its ability to regulate collagen formation (Westermann et al. 2008). It is tempting to speculate that SLRPs may have different functions resulting in different biological outcomes, depending on whether these molecules are soluble and can engage cell surface receptors or are incorporated in the ECM and are therefore unable to act as receptor ligands. Further investigations are warranted to elucidate the role of biglycan in inflammation and fibrogenesis.

Future perspectives

Taking into account the many modulatory functions exhibited by SLRPs at the molecular and cellular levels, i.e. controlling morphogenesis, cellular growth, apoptosis and inflammation among other functions, makes the study of SLRPs as matricellular proteins aptly worthwhile. Future research should aim at translating our rapidly expanding knowledge of these matricellular proteins into the clinical setting by identifying promising drug targets and defining new therapeutic strategies to treat inflammatory, fibrotic, and malignant disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 815, project A5; SCHA 1082/2-1; Excellence Cluster ECCPS), by the Frankfurt International Research Graduate School for Translational Biomedicine and Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung. We thank Chad Casey for his support with the graphical design.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- ASC

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing caspase activation and recruitment domain

- beta ig-h3

TGF-β inducible gene-h3

- BMP

bone morphogenic protein

- cdk

cyclin-dependent kinase

- CS

chondroitin sulphate

- CXCL1

CXC-Chemokine KC

- DS

dermatan sulphate

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF-R

epidermal growth factor receptor

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- IGF-IR

Insulin like growth factor receptor-I

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KS

keratan sulphate

- LRP-1

low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein

- LRRs

leucine-rich repeats

- MAGP-1

microfibril-associated glycoprotein 1

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NLRP3

NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3

- NLRs

nucleotide binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors

- PAMPs

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- SLRPs

small leucine-rich proteoglycans

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TLRs

toll-like receptors

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VEGF-R2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2

- VWF

von Willebrand factor

- WISP-I

Wnt-I induced secreted protein

- Xnr2

Xenopus nodal-related protein-2

References

- Abdel-Wahab N, Wicks SJ, Mason RM, Chantry A. Decorin suppresses transforming growth factor-beta-induced expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in human mesangial cells through a mechanism that involves Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of Smad2 at serine-240. Biochem J. 2002;362:643–649. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Haj Zen A, Caligiuri G, Sainz J, Lemitre M, Demerens C, Lafont A. Decorin overexpression reduces atherosclerosis development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameye L, Aria D, Jepsen K, Oldberg A, Xu T, Young MF. Abnormal collagen fibrils in tendons of biglycan/fibromodulin-deficient mice lead to gait impairment, ectopic ossification, and osteoarthritis. FASEB J. 2002;16:673–680. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0848com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babelova A, Moreth K, Tsalastra-Greul W, Zeng-Brouwers J, Eickelberg O, Young MF, Bruckner P, Pfeilschifter J, Schaefer RM, Groene HJ, Schaefer L. Biglycan: A danger signal that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via toll-like and P2X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24035–24048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y, Stuelten CH, Kilts T, Wadhwa S, Iozzo RV, Robey PG, Chen XD, Young MF. Extracellular matrix proteoglycans control the fate of bone marrow stromal cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30481–30489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y, Ehirchiou D, Kilts TM, Inkson CA, Embree MC, Sonoyama W, Li L, Leet AI, Seo BM, Zhang L, Shi S, Young MF. Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their niche. Nat Med. 2007;13:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/nm1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi X, Tong C, Dockendorff A, Bancroft L, Gallagher L, Guzman G, Iozzo RV, Augenlicht LH, Yang W. Genetic deficiency of decorin causes intestinal tumor formation through disruption of intestinal cell maturation. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1435–1440. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidanset DJ, Guidry C, Rosenberg LC, Choi HU, Timpl R, Hook M. Binding of the proteoglycan decorin to collagen type VI. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5250–5256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Border WA, Noble NA, Yamamoto T, Harper JR, Yamaguchi Y, Pierschbacher MD, Ruoslahti E. Natural inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta protects against scarring in experimental kidney disease. Nature. 1992;360:361–364. doi: 10.1038/360361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandan E, Retamal C, Cabello-Verrugio C, Marzolo MP. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein functions as an endocytic receptor for decorin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31562–31571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandan E, Cabello-Verrugio C, Vial C. Novel regulatory mechanisms for the proteoglycans decorin and biglycan during muscle formation and muscular dystrophy. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:700–708. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezillon S, Venteo L, Ramont L, D’Onofrio MF, Perreau C, Pluot M, Maquart FX, Wegrowski Y. Expression of lumican, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan with antitumour activity, in human malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:405–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EC, Lin M, Liu CY, Kao WW, Perez VL, Pearlman E. Keratocan and lumican regulate neutrophil infiltration and corneal clarity in lipopolysaccharide-induced keratitis by direct interaction with CXCL1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35502–35509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705823200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S, Magnuson T, Lass JH, Jepsen KJ, LaMantia C, Carroll H. Lumican regulates collagen fibril assembly: skin fragility and corneal opacity in the absence of lumican. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1277–1286. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti S, Petroll WM, Hassell JR, Jester JV, Lass JH, Paul J, Birk DE. Corneal opacity in lumican-null mice: defects in collagen fibril structure and packing in the posterior stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3365–3373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XD, Shi S, Xu T, Robey PG, Young MF. Age-related osteoporosis in biglycan-deficient mice is related to defects in bone marrow stromal cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:331–340. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XD, Fisher LW, Robey PG, Young MF. The small leucine-rich proteoglycan biglycan modulates BMP-4-induced osteoblast differentiation. FASEB J. 2004;18:948–958. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0899com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comalada M, Cardo M, Xaus J, Valledor AF, Lloberas J, Ventura F, Celada A. Decorin reverses the repressive effect of autocrine-produced TGF-beta on mouse macrophage activation. J Immunol. 2003;170:4450–4456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi A, Xu T, Chen XD, Boyde A, Liang J, Mankani M, Sommer B, Iozzo RV, Eichstetter I, Robey PG, Bianco P, Young MF. Phenotypic effects of biglycan deficiency are linked to collagen fibril abnormalities, are synergized by decorin deficiency, and mimic Ehlers-Danlos-like changes in bone and other connective tissues. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1180–1189. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.7.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas G, Santra M, Reed CC, Eichstetter I, McQuillan DJ, Gross D, Nugent MA, Hajnoczky G, Iozzo RV. Sustained down-regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by decorin. A mechanism for controlling tumor growth in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32879–32887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:729–743. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca A, Santra M, Baldi A, Giordano A, Iozzo RV. Decorin-induced growth suppression is associated with up-regulation of p21, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18961–18965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnoyers L, Arnott D, Pennica D. WISP-1 binds to decorin and biglycan. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47599–47607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas T, Heinemann S, Bierbaum S, Scharnweber D, Worch H. Fibrillogenesis of collagen types I, II, and III with small leucine-rich proteoglycans decorin and biglycan. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2388–2393. doi: 10.1021/bm0603746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehnis T, Dieterich W, Bauer M, Kresse H, Schuppan D. Localization of a binding site for the proteoglycan decorin on collagen XIV (undulin) J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20414–20419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elefteriou F, Exposito JY, Garrone R, Lethias C. Binding of tenascin-X to decorin. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:44–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezura Y, Chakravarti S, Oldberg A, Chervoneva I, Birk DE. Differential expression of lumican and fibromodulin regulate collagen fibrillogenesis in developing mouse tendons. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:779–788. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.4.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler LR, Schonherr E, Waddington R, Niland S, Seidler DG, Aeschlimann D, Eble JA. Decorin regulates endothelial cell motility on collagen I through activation of insulin-like growth factor I receptor and modulation of alpha2beta1 integrin activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17406–17415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JW, Kinsella MG, Levkau B, Clowes AW, Wight TN. Retroviral overexpression of decorin differentially affects the response of arterial smooth muscle cells to growth factors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:777–784. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font B, Eichenberger D, Goldschmidt D, Boutillon MM, Hulmes DJ. Structural requirements for fibromodulin binding to collagen and the control of type I collagen fibrillogenesis–critical roles for disulphide bonding and the C-terminal region. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:580–587. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui N, Fukuda A, Kojima K, Nakajima K, Oda H, Nakamura K. Suppression of fibrous adhesion by proteoglycan decorin. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:456–462. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburgh JL, Mitschler RR, Funderburgh ML, Roth MR, Chapes SK, Conrad GW. Macrophage receptors for lumican. A corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1159–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fust A, LeBellego F, Iozzo RV, Roughley PJ, Ludwig MS. Alterations in lung mechanics in decorin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L159–166. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00089.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi NS, Mancera RL. The structure of glycosaminoglycans and their interactions with proteins. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;72:455–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y, McQuillan D, Roughley PJ. SLRP interaction can protect collagen fibrils from cleavage by collagenases. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.08.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldoni S, Iozzo RV. Tumor microenvironment: Modulation by decorin and related molecules harboring leucine-rich tandem motifs. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2473–2479. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldoni S, Humphries A, Nystrom A, Sattar S, Owens RT, McQuillan DJ, Ireton K, Iozzo RV (2009) Decorin is a novel antagonistic ligand of the Met receptor. J Cell Biol jcb.200901129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Grisanti S, Szurman P, Warga M, Kaczmarek R, Ziemssen F, Tatar O, Bartz-Schmidt KU. Decorin modulates wound healing in experimental glaucoma filtration surgery: a pilot study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:191–196. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Wada Y. Effect of exogenous decorin on cell morphology and attachment of decorin-deficient fibroblasts. J Biochem. 1996;119:743–748. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti G, Bertoni A, Viola M, Tira E, Balduini C, Torti M. The small proteoglycan decorin supports adhesion and activation of human platelets. Blood. 2002;100:1707–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti GF, Bartolini B, Bernardi B, Tira ME, Berndt MC, Balduini C, Torti M. Binding of von Willebrand factor to the small proteoglycan decorin. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser H, Groning A, Hasilik A, Schonherr E, Kresse H. Selective inactivity of TGF-beta/decorin complexes. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:243–245. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heegaard AM, Corsi A, Danielsen CC, Nielsen KL, Jorgensen HL, Riminucci M, Young MF, Bianco P. Biglycan deficiency causes spontaneous aortic dissection and rupture in mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2731–2738. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson TD (2009) Renal Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis: Common but Never Simple. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hildebrand A, Romaris M, Rasmussen LM, Heinegard D, Twardzik DR, Border WA, Ruoslahti E. Interaction of the small interstitial proteoglycans biglycan, decorin and fibromodulin with transforming growth factor beta. Biochem J. 1994;302(Pt 2):527–534. doi: 10.1042/bj3020527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking AM, Shinomura T, McQuillan DJ. Leucine-rich repeat glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix. Matrix Biol. 1998;17:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijun W, Long C, Zhigang Z, Feng J, Muyi G. Ex vivo transfer of the decorin gene into rat glomerulus via a mesangial cell vector suppressed extracellular matrix accumulation in experimental glomerulonephritis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2005;78:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzelmann N, Anders S, Sollberg S, Schonherr E, Krieg T. Co-ordinate induction of collagen type I and biglycan expression in keloids. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:394–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley-Jones J, Robertson DL, Boot-Handford RP. On the origins of the extracellular matrix in vertebrates. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JY, Johnson PY, Braun KR, Hinek A, Fischer JW, O’Brien KD, Starcher B, Clowes AW, Merrilees MJ, Wight TN. Retrovirally mediated overexpression of glycosaminoglycan-deficient biglycan in arterial smooth muscle cells induces tropoelastin synthesis and elastic fiber formation in vitro and in neointimae after vascular injury. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1919–1928. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacob D, Cai J, Tsonis M, Babwah A, Chakraborty C, Bhattacharjee RN, Lala PK. Decorin-mediated inhibition of proliferation and migration of the human trophoblast via different tyrosine kinase receptors. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6187–6197. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegawa S. Expression, regulation and function of asporin, a susceptibility gene in common bone and joint diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:724–728. doi: 10.2174/092986708783885237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inkson CA, Ono M, Bi Y, Kuznetsov SA, Fisher LW, Young MF. The potential functional interaction of biglycan and WISP-1 in controlling differentiation and proliferation of osteogenic cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189:153–157. doi: 10.1159/000151377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV. The family of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: key regulators of matrix assembly and cellular growth. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:141–174. doi: 10.3109/10409239709108551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV. Matrix proteoglycans: from molecular design to cellular function. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:609–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV. The biology of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Functional network of interactive proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18843–18846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV, Moscatello DK, McQuillan DJ, Eichstetter I. Decorin is a biological ligand for the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4489–4492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaka Y, Brees DK, Ikegaya K, Kaneda Y, Imai E, Noble NA, Border WA. Gene therapy by skeletal muscle expression of decorin prevents fibrotic disease in rat kidney. Nat Med. 1996;2:418–423. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamajski S, Oldberg A. Homologous sequence in lumican and fibromodulin leucine-rich repeat 5–7 competes for collagen binding. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:534–539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene DR, San Antonio JD, Mayne R, McQuillan DJ, Sarris G, Santoro SA, Iozzo RV. Decorin binds near the C terminus of type I collagen. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21801–21804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielty CM, Whittaker SP, Shuttleworth CA. Fibrillin: evidence that chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans are components of microfibrils and associate with newly synthesised monomers. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielty CM, Sherratt MJ, Shuttleworth CA. Elastic fibres. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2817–2828. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.14.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaya K, Yasuo T. Dermatan sulfate proteoglycan biglycan as a potential selectin L/CD44 ligand involved in selective recruitment of peripheral blood CD16(-) natural killer cells into human endometrium. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:391–400. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0908535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb M, Margetts PJ, Sime PJ, Gauldie J. Proteoglycans decorin and biglycan differentially modulate TGF-beta-mediated fibrotic responses in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L1327–1334. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koninger J, Giese NA, Bartel M, di Mola FF, Berberat PO, di Sebastiano P, Giese T, Buchler MW, Friess H. The ECM proteoglycan decorin links desmoplasia and inflammation in chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:21–27. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.023135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse H, Schonherr E. Proteoglycans of the extracellular matrix and growth control. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:266–274. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse H, Hausser H, Schonherr E. Small proteoglycans. Experientia. 1993;49:403–416. doi: 10.1007/BF01923585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse H, Liszio C, Schonherr E, Fisher LW. Critical role of glutamate in a central leucine-rich repeat of decorin for interaction with type I collagen. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18404–18410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna P, Rosen CA, Branski RC, Wells A, Hebda PA. Primed fibroblasts and exogenous decorin: potential treatments for subacute vocal fold scar. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:937–945. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama S, Lupo G, Ohta K, Ohnuma S, Harris WA, Tanaka H. Tsukushi controls ectodermal patterning and neural crest specification in Xenopus by direct regulation of BMP4 and X-delta-1 activity. Development. 2006;133:75–88. doi: 10.1242/dev.02178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Aoki T, Mori Y, Ahmad M, Miyamori H, Takino T, Sato H. Cleavage of lumican by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 abrogates this proteoglycan-mediated suppression of tumor cell colony formation in soft agar. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7058–7064. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, McFarland DC, Velleman SG. Extracellular matrix proteoglycan decorin-mediated myogenic satellite cell responsiveness to transforming growth factor-beta1 during cell proliferation and differentiation Decorin and transforming growth factor-beta1 in satellite cells. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2008;35:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markmann A, Hausser H, Schonherr E, Kresse H. Influence of decorin expression on transforming growth factor-beta-mediated collagen gel retraction and biglycan induction. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:631–636. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan PA, Scott PG, Bishop PN, Bella J. Structural correlations in the family of small leucine-rich repeat proteins and proteoglycans. J Struct Biol. 2006;155:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melrose J, Fuller ES, Roughley PJ, Smith MM, Kerr B, Hughes CE, Caterson B, Little CB. Fragmentation of decorin, biglycan, lumican and keratocan is elevated in degenerate human meniscus, knee and hip articular cartilages compared with age-matched macroscopically normal and control tissues. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R79. doi: 10.1186/ar2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline R, Lazaroski S, Babelova A, Tsalastra-Greul W, Pfeilschifter J, Schlütter KD, Günther A, Iozzo RV, Schaefer RM, Schaefer L (2009) Decorin deficiency in diabetic mice: Aggravation of nephropathy due to overexpression of profibrotic factors, enhanced apoptosis and mononuclear cell infiltration. J Physiol Pharmacol 60, Suppl 4 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miura T, Kishioka Y, Wakamatsu J, Hattori A, Hennebry A, Berry CJ, Sharma M, Kambadur R, Nishimura T. Decorin binds myostatin and modulates its activity to muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M, Munoz R, Aroca F, Labarca M, Brandan E, Larrain J. Biglycan is a new extracellular component of the Chordin-BMP4 signaling pathway. EMBO J. 2005;24:1397–1405. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SA, Almeida AD, Tanaka H, Ohta K, Ohnuma S. Tsukushi modulates Xnr2. FGF and BMP signaling: regulation of Xenopus germ layer formation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscatello DK, Santra M, Mann DM, McQuillan DJ, Wong AJ, Iozzo RV. Decorin suppresses tumor cell growth by activating the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:406–412. doi: 10.1172/JCI846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito Z. Role of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP) family in pathological lesions and cancer cell growth. J Nippon Med Sch. 2005;72:137–145. doi: 10.1272/jnms.72.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Kizawa H, Saitoh M, Kou I, Miyazono K, Ikegawa S. Mechanisms for asporin function and regulation in articular cartilage. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32185–32192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neame PJ, Kay CJ, McQuillan DJ, Beales MP, Hassell JR. Independent modulation of collagen fibrillogenesis by decorin and lumican. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:859–863. doi: 10.1007/s000180050048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitovic D, Berdiaki K, Chalkiadaki G, Karamanos N, Tzanakakis G. The role of SLRP-proteoglycans in osteosarcoma pathogenesis. Connect Tissue Res. 2008;49:235–238. doi: 10.1080/03008200802147589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitovic D, Katonis P, Tsatsakis A, Karamanos NK, Tzanakakis GN. Lumican, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:818–823. doi: 10.1002/iub.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nili N, Cheema AN, Giordano FJ, Barolet AW, Babaei S, Hickey R, Eskandarian MR, Smeets M, Butany J, Pasterkamp G, Strauss BH. Decorin inhibition of PDGF-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell function: potential mechanism for inhibition of intimal hyperplasia after balloon angioplasty. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:869–878. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63447-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta K, Kuriyama S, Okafuji T, Gejima R, Ohnuma S, Tanaka H. Tsukushi cooperates with VG1 to induce primitive streak and Hensen’s node formation in the chick embryo. Development. 2006;133:3777–3786. doi: 10.1242/dev.02579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrimon N, Bernfield M. Cellular functions of proteoglycans–an overview. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12:65–67. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle GA, Dodd CM. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of the core protein of decorin near the d and e bands of tendon collagen fibrils by use of monoclonal antibodies. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:1405–1411. doi: 10.1177/38.10.1698203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspanti M, Viola M, Forlino A, Tenni R, Gruppi C, Tira ME. Glycosaminoglycans show a specific periodic interaction with type I collagen fibrils. J Struct Biol. 2008;164:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CC, Iozzo RV. The role of decorin in collagen fibrillogenesis and skin homeostasis. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:249–255. doi: 10.1023/A:1025383913444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CC, Gauldie J, Iozzo RV. Suppression of tumorigenicity by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of decorin. Oncogene. 2002;21:3688–3695. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinboth B, Hanssen E, Cleary EG, Gibson MA. Molecular interactions of biglycan and decorin with elastic fiber components: biglycan forms a ternary complex with tropoelastin and microfibril-associated glycoprotein 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3950–3957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinboth B, Thomas J, Hanssen E, Gibson MA. Beta ig-h3 interacts directly with biglycan and decorin, promotes collagen VI aggregation, and participates in ternary complexing with these macromolecules. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7816–7824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughley PJ. The structure and function of cartilage proteoglycans. Eur Cell Mater. 2006;12:92–101. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v012a11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhland C, Schonherr E, Robenek H, Hansen U, Iozzo RV, Bruckner P, Seidler DG. The glycosaminoglycan chain of decorin plays an important role in collagen fibril formation at the early stages of fibrillogenesis. FEBS J. 2007;274:4246–4255. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Martin S, Zorn TM. The small proteoglycan biglycan is associated with thick collagen fibrils in the mouse decidua. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2003;49:673–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra M, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. Decorin binds to a narrow region of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, partially overlapping but distinct from the EGF-binding epitope. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35671–35681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Biological functions of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: from genetics to signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21305–21309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800020200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Schaefer RM (2009) Proteoglycans: from structural compounds to signaling molecules. Cell Tissue Res Jun 10. [Epub ahead of print], PMID: 19513755 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schaefer L, Raslik I, Grone HJ, Schonherr E, Macakova K, Ugorcakova J, Budny S, Schaefer RM, Kresse H. Small proteoglycans in human diabetic nephropathy: discrepancy between glomerular expression and protein accumulation of decorin, biglycan, lumican, and fibromodulin. FASEB J. 2001;15:559–561. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0493fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Macakova K, Raslik I, Micegova M, Grone HJ, Schonherr E, Robenek H, Echtermeyer FG, Grassel S, Bruckner P, Schaefer RM, Iozzo RV, Kresse H. Absence of decorin adversely influences tubulointerstitial fibrosis of the obstructed kidney by enhanced apoptosis and increased inflammatory reaction. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1181–1191. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64937-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Beck KF, Raslik I, Walpen S, Mihalik D, Micegova M, Macakova K, Schonherr E, Seidler DG, Varga G, Schaefer RM, Kresse H, Pfeilschifter J. Biglycan, a nitric oxide-regulated gene, affects adhesion, growth, and survival of mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26227–26237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Mihalik D, Babelova A, Krzyzankova M, Grone HJ, Iozzo RV, Young MF, Seidler DG, Lin G, Reinhardt DP, Schaefer RM. Regulation of fibrillin-1 by biglycan and decorin is important for tissue preservation in the kidney during pressure-induced injury. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:383–396. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Babelova A, Kiss E, Hausser HJ, Baliova M, Krzyzankova M, Marsche G, Young MF, Mihalik D, Gotte M, Malle E, Schaefer RM, Grone HJ. The matrix component biglycan is proinflammatory and signals through Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2223–2233. doi: 10.1172/JCI23755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Tsalastra W, Babelova A, Baliova M, Minnerup J, Sorokin L, Grone HJ, Reinhardt DP, Pfeilschifter J, Iozzo RV, Schaefer RM. Decorin-mediated regulation of fibrillin-1 in the kidney involves the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and Mammalian target of rapamycin. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:301–315. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonherr E, Hausser H, Beavan L, Kresse H. Decorin-type I collagen interaction. Presence of separate core protein-binding domains. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8877–8883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonherr E, Witsch-Prehm P, Harrach B, Robenek H, Rauterberg J, Kresse H. Interaction of biglycan with type I collagen. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2776–2783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonherr E, Broszat M, Brandan E, Bruckner P, Kresse H. Decorin core protein fragment Leu155-Val260 interacts with TGF-beta but does not compete for decorin binding to type I collagen. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;355:241–248. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonherr E, Schaefer L, O’Connell BC, Kresse H. Matrix metalloproteinase expression by endothelial cells in collagen lattices changes during co-culture with fibroblasts and upon induction of decorin expression. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:37–47. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(2001)9999:9999<::AID-JCP1048>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonherr E, Sunderkotter C, Schaefer L, Thanos S, Grassel S, Oldberg A, Iozzo RV, Young MF, Kresse H. Decorin deficiency leads to impaired angiogenesis in injured mouse cornea. J Vasc Res. 2004;41:499–508. doi: 10.1159/000081806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonherr E, Sunderkotter C, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Decorin, a novel player in the insulin-like growth factor system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15767–15772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler DG, Goldoni S, Agnew C, Cardi C, Thakur ML, Owens RT, McQuillan DJ, Iozzo RV. Decorin protein core inhibits in vivo cancer growth and metabolism by hindering epidermal growth factor receptor function and triggering apoptosis via caspase-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26408–26418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YF, Zhang Q, Cheung PY, Shi L, Fong CC, Zhang Y, Tzang CH, Chan BP, Fong WF, Chun J, Kung HF, Yang M. Effects of rhDecorin on TGF-beta1 induced human hepatic stellate cells LX-2 activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:1587–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu-Hirota R, Sasamura H, Kuroda M, Kobayashi E, Hayashi M, Saruta T. Extracellular matrix glycoprotein biglycan enhances vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Circ Res. 2004;94:1067–1074. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126049.79800.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifaki M, Assouti M, Nikitovic D, Krasagakis K, Karamanos NK, Tzanakakis GN. Lumican, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan substituted with keratan sulfate chains is expressed and secreted by human melanoma cells and not normal melanocytes. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:606–610. doi: 10.1080/15216540600951605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg AP, Manderson GA, Morgelin M, Day AJ, Heinegard D, Blom AM. Short leucine-rich glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix display diverse patterns of complement interaction and activation. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:830–839. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L, Heinegard D, Oldberg A. Decorin-binding sites for collagen type I are mainly located in leucine-rich repeats 4–5. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20712–20716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L, Aszodi A, Reinholt FP, Fassler R, Heinegard D, Oldberg A. Fibromodulin-null mice have abnormal collagen fibrils, tissue organization, and altered lumican deposition in tendon. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9636–9647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y, Kodama Y, Matsumoto T. Bone matrix decorin binds transforming growth factor-beta and enhances its bioactivity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32634–32638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tralhao JG, Schaefer L, Micegova M, Evaristo C, Schonherr E, Kayal S, Veiga-Fernandes H, Danel C, Iozzo RV, Kresse H, Lemarchand P. In vivo selective and distant killing of cancer cells using adenovirus-mediated decorin gene transfer. FASEB J. 2003;17:464–466. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0534fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask BC, Trask TM, Broekelmann T, Mecham RP. The microfibrillar proteins MAGP-1 and fibrillin-1 form a ternary complex with the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan decorin. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1499–1507. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufvesson E, Westergren-Thorsson G. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha interacts with biglycan and decorin. FEBS Lett. 2002;530:124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufvesson E, Westergren-Thorsson G. Biglycan and decorin induce morphological and cytoskeletal changes involving signalling by the small GTPases RhoA and Rac1 resulting in lung fibroblast migration. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4857–4864. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vij N, Roberts L, Joyce S, Chakravarti S. Lumican suppresses cell proliferation and aids Fas-Fas ligand mediated apoptosis: implications in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:957–971. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vij N, Roberts L, Joyce S, Chakravarti S. Lumican regulates corneal inflammatory responses by modulating Fas-Fas ligand signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:88–95. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola M, Bartolini B, Sonaggere M, Giudici C, Tenni R, Tira ME. Fibromodulin interactions with type I and II collagens. Connect Tissue Res. 2007;48:141–148. doi: 10.1080/03008200701276133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuillermoz B, Khoruzhenko A, D’Onofrio MF, Ramont L, Venteo L, Perreau C, Antonicelli F, Maquart FX, Wegrowski Y. The small leucine-rich proteoglycan lumican inhibits melanoma progression. Exp Cell Res. 2004;296:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington RJ, Roberts HC, Sugars RV, Schonherr E. Differential roles for small leucine-rich proteoglycans in bone formation. Eur Cell Mater. 2003;6:12–21. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v006a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber IT, Harrison RW, Iozzo RV. Model structure of decorin and implications for collagen fibrillogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31767–31770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber CK, Sommer G, Michl P, Fensterer H, Weimer M, Gansauge F, Leder G, Adler G, Gress TM. Biglycan is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer and induces G1-arrest in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:657–667. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis SM, Zimmerman SD, Shah M, Covell JW, Omens JH, Ross J, Jr, Dalton N, Jones Y, Reed CC, Iozzo RV, McCulloch AD. A role for decorin in the remodeling of myocardial infarction. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann D, Mersmann J, Melchior A, Freudenberger T, Petrik C, Schaefer L, Lullmann-Rauch R, Lettau O, Jacoby C, Schrader J, Brand-Herrmann SM, Young MF, Schultheiss HP, Levkau B, Baba HA, Unger T, Zacharowski K, Tschope C, Fischer JW. Biglycan is required for adaptive remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:1269–1276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.714147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]