Abstract

Aβ1–42 is a self-associating peptide whose neurotoxic derivatives are thought to play a role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Neurotoxicity of amyloid β protein (Aβ) has been attributed to its fibrillar forms, but experiments presented here characterize neurotoxins that assemble when fibril formation is inhibited. These neurotoxins comprise small diffusible Aβ oligomers (referred to as ADDLs, for Aβ-derived diffusible ligands), which were found to kill mature neurons in organotypic central nervous system cultures at nanomolar concentrations. At cell surfaces, ADDLs bound to trypsin-sensitive sites and surface-derived tryptic peptides blocked binding and afforded neuroprotection. Germ-line knockout of Fyn, a protein tyrosine kinase linked to apoptosis and elevated in Alzheimer’s disease, also was neuroprotective. Remarkably, neurological dysfunction evoked by ADDLs occurred well in advance of cellular degeneration. Without lag, and despite retention of evoked action potentials, ADDLs inhibited hippocampal long-term potentiation, indicating an immediate impact on signal transduction. We hypothesize that impaired synaptic plasticity and associated memory dysfunction during early stage Alzheimer’s disease and severe cellular degeneration and dementia during end stage could be caused by the biphasic impact of Aβ-derived diffusible ligands acting upon particular neural signal transduction pathways.

Progressive dementia in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with selective neuronal degeneration and death (1). Causes remain uncertain, but the amyloid hypothesis, which states that central nervous system (CNS) build-up of amyloid β peptide (Aβ) is neurotoxic, has received increasing support (2). Neurotoxicity in cell culture (3, 4) depends on Aβ self-association (5). Self-association occurs faster for the longer, more hydrophobic forms of Aβ (i.e., Aβ1–42 versus Aβ1–40; see refs. 6 and 7). Aβ1–42 is more abundant in AD brain tissue than in age-matched controls (8), and production of Aβ1–42 in cell transfection experiments is increased by APP and presenilin mutations that cause AD (9, 10). ApoE4 alleles, which increase risk of AD, also increase Aβ accumulation (11). Recently, transgenic expression of human genes linked to elevated Aβ1–42 has produced mice that exhibit certain Alzheimer’s-like molecular, cellular, and behavioral phenotypes (12–14).

Despite its support, the amyloid hypothesis has been widely challenged (15). An imperfect correlation exists between amyloid deposits and dementia (16, 17), and doses of fibrillar Aβ needed to kill neurons in culture appear excessive (18). An underappreciated possibility is that Aβ may give rise to small toxic derivatives other than the highly aggregated species found in amyloid deposits (19, 20). Although significant support exists for the idea that toxic forms of Aβ comprise large fibrils (21, 22), these experiments typically have been carried out with pure Aβ allowed to aggregate out of homogeneous solutions. Aβ, however, selectively interacts with various molecules, including proteins found in neuritic plaques (20, 23–28).

An appealing hypothesis is that other molecules elevated in AD brain may chaperone Aβ1–42 self-association, leading to toxic Aβ oligomers that are diffusible and potentially more pernicious than fibrillar Aβ. Support for this hypothesis comes from recent findings that low amounts of clusterin (Apo J), a senile plaque protein, give rise to slowly sedimenting Aβ derivatives with enhanced mitochondrial toxicity in neuron-like PC12 cells (19, 20). We now have found that these slowly sedimenting neurotoxins comprise soluble, ligand-like Aβ1–42 oligomers that are nonfibrillar, readily diffusible, and toxic to mature CNS neurons at nanomolar concentrations. Current data suggest that Aβ-derived diffusible ligand (ADDL) toxicity depends on cell surface toxin receptors and Fyn, a nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinase that is overexpressed in AD (29).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and Characterization of ADDLs.

Unless stated otherwise, ADDL solutions were prepared by incubating Aβ1–42 (see ref. 30 for synthesis) for 24 hr with clusterin (as described in ref. 20). Solutions were centrifuged (14,000 × g for 10 min), and the supernatant was used for all assays. ADDLs also were prepared without clusterin in two ways: (i) Aβ1–42 was brought to 100 μM in cold F12 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), the solution vortexed, incubated at 4–8°C for 24 hr, and centrifuged as above; and (ii) Aβ1–42 was brought to 50 nM in 37°C brain slice culture medium (see below) for 24 hr and used directly.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM).

AFM was carried out essentially as described (31). At least four regions of the mica surface were examined to ensure that similar structures existed throughout the sample. Images presented are top view subtracted images containing both height and error channel data.

Gel electrophoresis and immunoblots.

Nondenaturing electrophoresis for ADDL analysis used separation on 4–20% Tris-glycine gels (Novex, San Diego) at 20 mA for 1.5 hr; SDS/PAGE was as described (32). Proteins were visualized by silver stain (33). For immunoblots, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (32), incubated with biotinylated 6E10 antibody (Senetek, St. Louis, MO) at 1:2,000 and visualized by ECL (Amersham). Molecular mass was estimated with MultiMark standards (Novex).

Mouse Brain Slice Culture and Assay for Viability.

Brain slices from strain (B6 × 129)F2/J and strain JR 2385 (The Jackson Laboratories) were cultured as described (34), except growth medium was DMEM, 10% fetal calf serum, and antibiotic/antimycotic (all from Life Technologies), and horizontal slices of 200 μm were used. After overnight culture, medium was changed to defined medium (DMEM, N2 supplements antibiotic/antimycotic) with or without ADDLs. Viability was assessed after 24 hr by Live/Dead two-color fluorescence assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Probes). Slices were washed in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) and exposed to 4μm calcein-AM and 2 μM ethidium homodimer in HBSS for 20 min at 37°C. Dye uptake was detected by using a Nikon Diaphot with filter cubes for fluorescein (for calcein in live cells) and Texas red (for ethidium homodimer in dead cells). Image analysis to quantify Live/Dead fluorescence was performed by using metamorph (Universal Imaging, Philadelphia).

Binding of ADDLs to Cell Surfaces.

Cell suspensions (2.5 × 105 cells/500 μl PBS) were incubated with 5 μM ADDLs at 4°C for 1 hr. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 500 μl ice-cold PBS and incubated with biotinylated 6E10 mAb (1 μl; Senetek) for 30 min. Cell were washed and then incubated in 500 μl PBS with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated streptavidin (1:500; Amersham) for 30 min. Relative binding was quantified by FACScan (Becton Dickinson), multiplying mean fluorescence by total number of events, and subtracting values for background cell fluorescence in the presence of 6E10 and secondary antibody.

Preparation of Tryptic Peptides.

Confluent B103 cells (35) were removed by trypsinization (0.25%; Life Technologies) for ≈3 min. Trypsin-chymotrypsin inhibitor (Sigma; 0.5 mg/ml in Hanks’ buffered saline) was added, and cells were pelleted via centrifugation (500 × g, 5 min). Supernatant (≈12 ml) was concentrated to ≈1.0 ml by using a Centricon 3 filter (Amicon) and frozen after protein concentration was determined. For blocking experiments, sterile concentrated tryptic peptides (0.25 mg/ml) were added at the same time as ADDLs.

Electrophysiology.

Long-term potentiation (LTP) experiments were performed on P21 rat hippocampal slices, as described (36).

RESULTS

ADDLs: Aβ-Derived Neurotoxins That Are Soluble and Fibril-Free.

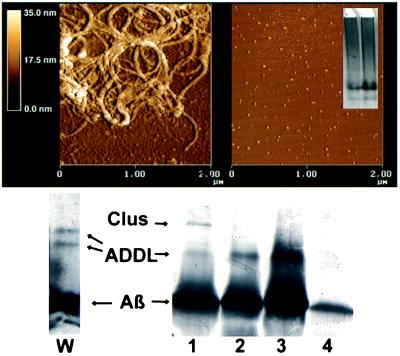

Although the toxic form of Aβ putatively is fibrillar (21, 22), neurotoxins that do not behave as sedimentable fibrils will form when Aβ1–42 is incubated with clusterin (20). When examined by AFM, these preparations were completely fibril-free, exclusively comprising small globular structures (AFM; Fig. 1, Right). Equivalent results were obtained by conventional electron microscopy (data not shown). In contrast, Aβ1–42 that self-associated without clusterin under standard conditions (31) showed typical fibrillar structure (Fig. 1, Left). The fibril-free Aβ derivatives will be referred to as ADDLs.

Figure 1.

AFM and gel electrophoresis show that toxic ADDL preparations comprise small, fibril-free oligomers of Aβ1–42. AFM examination of toxic ADDLs shows small globular structures, ≈5–6 nm in size, and a distinct lack of fibrils, consistent with migration of ADDLs as oligomers during gel electrophoresis. (Upper Left) Examination of conventional Aβ preparations by AFM shows primarily large, nondiffusible fibrillar species. (Upper Right) ADDLs imaged by AFM show size and structure consistent with their diffusible nature. (Inset) Native gel of ADDLs made in the cold. Note two major species found at ≈27 and 17 kDa and the absence of large molecular weight species. (Lower Left) Lane W, SDS/PAGE (Western blot) using 6E10 antibody of ADDLs made in the cold. (Lower Right) SDS/PAGE, silver-stained. Lanes: 1, ADDLs made with clusterin; 2, ADDLs made in cold; 3, Centricon 10 retentate of cold-induced ADDLs; 4, Centricon 10 eluate of cold-induced ADDLs. The positions of clusterin monomer, Aβ1–42, and ADDLs are shown.

As done previously for fibrils (31), size characterization of ADDLs by AFM section analysis indicated that the predominant species were globules ≈4.8–5.7 nm along the z-axis. Comparison with small globular proteins (Aβ1–40 monomer, aprotinin, basic fibroblast growth factor, carbonic anhydrase) suggested that ADDLs had mass between 17 and 42 kDa.

ADDLs of this mass would be too small to contain clusterin (Mr 80,000), indicating a chaperone-like function for clusterin (present at molarity 1:40 relative to Aβ). To verify this, however, conditions were sought in which ADDLs could form without clusterin. It was found that ADDLs could form in clusterin-free Aβ solutions if incubation was at reduced temperature (4–8°C). Cold-induced ADDLs were indistinguishable from those chaperoned by clusterin. In addition, ADDLs could form in clusterin-free tissue culture medium held at 37°C if Aβ was very dilute (50 nM), consistent with a potential to form physiologically. Morphologically, all ADDL solutions were stable at least 24 hr.

The fibril-free nature of ADDLs established by AFM was verified by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. Nondenaturing gels showed ADDLs were oligomeric (Fig. 1, Inset), with the predominant species at 27 kDa and a minor species at 17 kDa. Western blot analysis of ADDL preparations resolved by SDS/PAGE showed similar bands at 22 and 17 kDa (Fig. 1, lane W). The presence of similar molecular weight Aβ species in nondenaturing and SDS gels indicates the oligomeric nature of ADDLs was not detergent-induced. Silver-stained SDS gels (Fig. 1, lanes 1–4) showed only the larger, more abundant ADDL oligomer, which was present whether ADDLs were clusterin- or cold-induced (lanes 1 and 2, respectively; lane 1 also shows the 40-kDa clusterin monomer). Monomeric Aβ seen in these SDS gels was not eliminated by prior Centricon 10 fractionation. Centricon retentate (lane 3) was indistinguishable from unfractionated ADDLs (lane 2), despite the ability of monomer to pass through the 10-kDa pore (eluate, lane 4). This result would be expected if the ADDLs were only partially detergent-stable.

Cell Death in Organotypic Mouse Brain Slice Cultures.

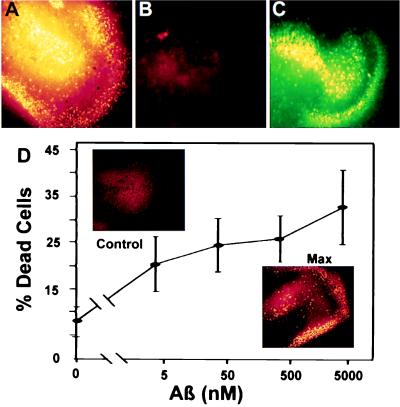

ADDL toxicity was tested in organotypic mouse brain slice cultures, which provided a physiologically relevant model for mature CNS. Whether induced by clusterin (Fig. 2), by low temperature, or by low Aβ concentration (data not shown), ADDLs were potent neurotoxins. To obtain high levels of viability in controls (below), cultures were supported by a filter at the medium–atmosphere interface. ADDLs thus had to pass through support filters to reach the cultures, showing a diffusible nature consistent with their small size.

Figure 2.

ADDLs are diffusible, extremely potent CNS neurotoxins. ADDLs in culture medium diffuse through culture support filters and cause extensive cell death in stratum granulosum (DG) and CA3 areas of organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. ADDL toxicity is extensive even at nanomolar doses, but nondiffusing fibrils at 20 μM are not toxic. (A) DG and CA3 area of a hippocampal slice treated for 24 hr with 5 μM ADDLs. Dead cells are highlighted in false yellow color (see Materials and Methods). Up to 40% of the cells in this region die following chronic exposure to ADDLs. (B) DG and CA3 area of another hippocampal slice treated with 20 μM fibrillar Aβ1–42 for 24 hr. No cell death is seen. (C) Live cells in the same area of the slice treated with fibrillar Aβ1–42. (D) ADDLs were added to duplicate mouse hippocampal slices for 24 hr at the indicated concentrations. The Live/Dead assay and image analysis (see Materials and Methods) were used to determine percent dead cells in fields containing the DG and CA3 areas. Data show that even after a 1,000-fold dilution to 5 nM Aβ1–42, ADDLs still kill >20% of the cells, a value greater than half the maximum cell death. (Inset) Comparison of cell death in DG and CA3 observed with vehicle alone (Upper) or with ADDLs at 5 μM (Lower). ADDL concentration was determined by measuring the supernatant protein and subtracting the amount of soluble clusterin present. This formula assumes the amount of clusterin that pellets is negligible.

Cell death, as shown by “false yellow staining” (Fig. 2A), was almost completely confined to the stratum pyramidale (CA3–CA4) and stratum granulosum (DG), suggesting strongly that principal neurons of the hippocampus (pyramidal and granule cells, respectively) were targets of ADDL-induced toxicity. Loss of other cell types cannot as yet be ruled out. Neurons but not astrocytes, however, were killed in dissociated hippocampal cell cultures (37) by 24-hr ADDL exposure (data not shown), consistent with the organotypic culture results. Organotypic cultures treated with conventional aggregated preparations of 20 μM Aβ had control-level cell death (Fig. 2 B and C), as expected from the nondiffusible nature of fibrils. Cell death in slices typically was less than 5% in controls with unsupplemented medium (Fig. 2D) or with clusterin (data not shown).

ADDLs Are Toxic at Nanomolar Doses.

ADDLs were diluted logarithmically to estimate their potency in evoking cell death (Fig. 2D). Fig 2D Inset illustrates null and maximal cell death responses. Image analysis was used to quantify dead cell and live cell staining in fields containing the DG/CA3 areas. Even after 1,000-fold dilution (5 nM Aβ), ADDL-evoked cell death was >20%, greater than half the maximum. This high potency, coupled with diffusibility demonstrated above, makes ADDL toxicity especially pernicious.

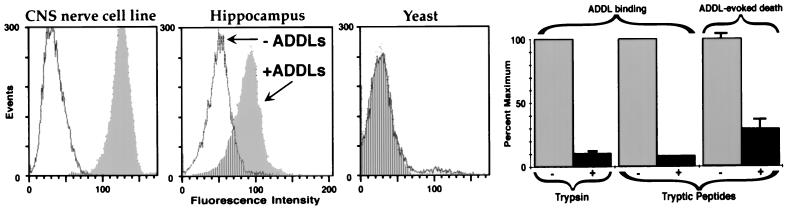

ADDLs Bind to Particular Cell Surface Proteins.

Toxin receptors recently have been identified for conventionally prepared fibrillar Aβ (38, 39). Because neuronal death at low ADDL doses suggested possible involvement of signaling mechanisms, experiments were undertaken to determine if specific cell surface binding sites existed for ADDLs. Fig. 3 shows FACScan analysis of ADDL immunoreactivity in suspensions of the B103 CNS neuronal cell line (35) and of dissociated hippocampal cells. For B103 cells, addition of ADDLs caused a large increase in cell-associated fluorescence. Suspensions of hippocampal cells also bound ADDLs, but less well than B103 cells. Because hippocampal tissue was trypsinized (with only a 2-hr recovery) to obtain cells for analysis, the relatively low level of binding might be caused by toxin receptor proteolysis, although this has yet to be established. However, yeast cells, which present primarily a carbohydrate surface, showed no ADDL-dependent fluorescence. Even brief trypsinization of B103 cell surfaces inhibited subsequent ADDL binding by more than 90% (Fig. 3). ADDL binding sites thus are found in the particular molecular moieties removed from the membrane by trypsin.

Figure 3.

Cell surface binding of ADDLs is selective and required for toxicity. FACScan shows that ADDL binding is robust in the B103 CNS nerve cell line, lowered in primary hippocampal cells, and completely absent in yeast cells. Consistent with selectivity, trypsinization of cell surfaces blocks subsequent ADDL binding; moreover, cell surface tryptic peptides are antagonists of ADDL binding and toxicity. FACScan assay. (Left) Suspensions of B103 rat neuroblastoma cells (Far Left), primary rat hippocampal cells (Center), and yeast cells (Right, Saccharomyces cerevisieae, log-phase) were incubated with ADDLs for 60 min and then assessed for the presence of bound ADDLs (Materials and Methods). White shows the background fluorescence in absence of ADDLs, gray the increased fluorescence because of addition of ADDLs, and stripes the background level fluorescence in ADDL-treated samples. Bar Graphs (Right) Quantitative comparison shows that ADDL binding in B103 cells is blocked ≈90% by brief trypsinization; furthermore, binding to cells is blocked ≈90% and cell death in the slice assay is blocked ≈75% by the addition of tryptic peptides (see Materials and Methods). Error bars are SEM for four or five replicate samples.

Consistent with removal of binding sites by trypsin, it was found that cell-surface tryptic peptides released into the culture medium (0.25 mg/ml) inhibited ADDL binding by >90% (Fig. 3 Right). Controls exposed to BSA, even at 100 mg/ml, had no loss of binding. Tryptic peptides, if added after ADDLs were already attached to cells, did not lower fluorescence intensities; the peptides thus did not compromise quantitation of bound ADDLs. Besides blocking ADDL binding, the tryptic peptides also inhibited ADDL-evoked cell death (Fig. 3; 75% reduction in cell death, P < 0.002). Overall, the data show that ADDL binding sites comprise particular domains of cell surface proteins and that these domains, when solubilized by trypsin, provide neuroprotective, ADDL-neutralizing activity.

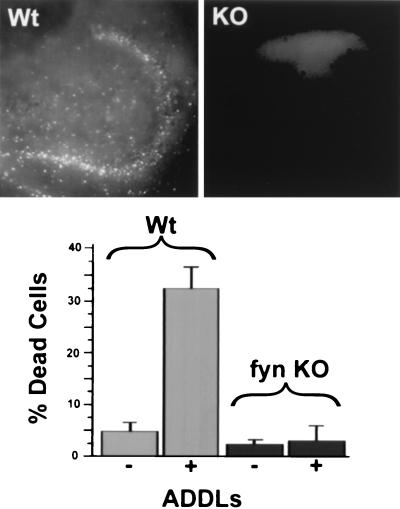

Fyn Kinase Knockout Protects Against ADDL Neurotoxicity.

The impact of ADDLs on brain slices was compared in isogenic fyn−/− and fyn+/+ animals. Fyn is up-regulated in AD-afflicted neurons (29) and belongs to the Src-family of protein tyrosine kinases, which are central to multiple cellular signals and responses (40). Fyn may be activated by conventional Aβ (41), and Fyn knockout mice have reduced apoptosis in developing hippocampus (42).

In hippocampal slices from Fyn knockout animals, ADDL-evoked cell death did not occur (Fig. 4 Upper Right). The amount of death in these slices was indistinguishable from controls (Fig. 4 Lower). Quantitatively, cell death with ADDLs present was five times greater in Fyn wild-type than in Fyn knockout slices. Analysis (ANOVA) with the Tukey multiple comparison gave a value of P < 0.001 for the ADDL Fyn wild-type data compared with all other conditions. Although loss of Fyn kinase clearly protected DG and CA3 hippocampal regions from cell death induced by ADDLs, the neuroprotective effect was selective; hippocampal cell death evoked by N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor agonists (43, 44) was unaffected (data not shown). Results establish that the mechanism through which ADDLs exerted their toxicity is blocked by knockout of Fyn protein tyrosine kinase.

Figure 4.

Hippocampal neurotoxicity of ADDLs occurs via a Fyn-dependent pathway. ADDL toxicity is completely blocked in slices from a Fyn knockout (KO) mouse. (Upper) Images of dead cells in the DG and CA3 area of (Left) Fyn wild-type or (Right) Fyn knockout mouse slice exposed to ADDLs for 24 hr. Cell death only occurs with Fyn wild-type genotype. (Lower) Quantitative comparison of cell death in Fyn wild-type and Fyn knockout slices. Error bars are means ± SEM for four to seven slices.

ADDLs Disrupt LTP.

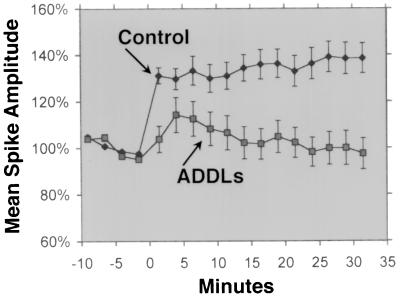

LTP is a classic paradigm for synaptic plasticity and a model for memory and learning, faculties that are selectively lost in early stage AD. Because of the importance of Fyn to LTP (42), experiments were done to examine the effects of ADDLs (made in the cold) on medial perforant path-granule cell LTP. In hippocampal slices from young adult rats, inhibition of LTP by ADDLs was clearly evident (Fig. 5). Hippocampal slices (n = 6) exposed to 500 nM ADDLs for 45 min prior showed no potentiation in the population spike 30 min after the tetanic stimulation (mean amplitude, 99 ± 7.6%). In contrast, LTP was readily induced in slices incubated with vehicle (n = 6), with an amplitude of 138 ± 8.1% for the last 10 min; this value is comparable to that previously demonstrated in this age group (36). Although LTP was absent in ADDL-treated slices, their cells were competent to generate action potentials and showed no signs of degeneration. Thus, in less than an hour, ADDLs disrupted LTP.

Figure 5.

ADDLs block LTP. Incubation of rat hippocampal slices with ADDLs prevents LTP well before any overt signs of cell degeneration. Medial perforant path-granule cell LTP was readily induced in slices from young adult rats (•, see Materials and Methods). In contrast, hippocampal slices exposed to ADDLs for 45 min showed no lasting potentiation (▪), despite a continuing capacity for evoked action potentials.

DISCUSSION

Experiments presented here characterize Aβ1–42 oligomers that are soluble and highly neurotoxic. These small oligomers (ADDLs) assemble under conditions that block fibril formation, and they kill hippocampal neurons at nanomolar concentrations. Although the basis for their potent toxicity is not known, ADDLs bind to cell surfaces at trypsin-sensitive domains, and tryptic peptides obtained from cell surfaces block ADDL binding and toxicity. ADDL-evoked cell death, moreover, is eliminated by germ-line knockout of Fyn, a protein tyrosine kinase elevated in AD-afflicted neurons (29) and linked to mechanisms of apoptosis (42) and LTP (42). Further association with hippocampal signal transduction was seen in a rapid inhibition of LTP, which occurred without lag. Loss of LTP was too fast to be explained by cell death and occurred despite continued capacity of hippocampal neurons for action potentials. We propose that in AD, early memory loss and subsequent catastrophic dementia could be caused by pathogenic ADDLs, which first disrupt synaptic plasticity and subsequently cause neuronal death via mechanisms that require specific binding and signal transduction molecules.

That small multimers of Aβ might be neurotoxic was first evident in the ability of slowly sedimenting, clusterin-chaperoned Aβ derivatives to compromise mitochondrial function in PC12 cells (19, 20). The current data show these derivatives are fibril-free, comprising small soluble Aβ oligomers. Absence of fibrils was verified by AFM, electron microscopy, and electrophoresis. Because oligomers were present in nondenaturing as well as SDS/PAGE, their small size could not be attributed to strong detergent action. The oligomers were relatively stable, and even SDS did not cause complete disassembly. ADDLs migrated at about 27 and 17 kDa in native gels, and at about 22 and 17 kDa on SDS gels, but the possibility that ADDLs move anomalously on gels makes these estimates only approximate. The larger species was more abundant in silver stained samples.

Whether ADDLs are present in normal or Alzheimer’s-afflicted human brain tissue is not yet known. This possibility is supported, however, by known interactions between clusterin and Aβ (28, 46–48). Like Aβ1–42 (29), clusterin is up-regulated in AD brain (19, 45, 49) and occurs in amyloid plaques (25), clearly in proximity to Aβ1–42. Fractionation experiments also have indicated the existence of water soluble oligomers of Aβ that are increased 12-fold in AD brains (50). Soluble Aβ also is increased in brains from Down’s patients (51). ADDL-like oligomers also occur spontaneously at very low concentrations in medium conditioned by amyloid precursor protein (APP)-transfected CHO cells (52); intriguingly, mutant presenilin genes, which elevate production of Aβ1–42 and are associated with familial AD, increase the abundance of these stable Aβ oligomers (53). As yet, the conditioned medium species have not been tested for toxicity. Reports of CNS degeneration in animals carrying a mutant APP transgene but lacking amyloid deposits (14) possibly could be explained by ADDL neurotoxicity in the transgenic animals.

Whereas our current and earlier reports (19, 20) showed that clusterin increases toxicity of Aβ1–42 solutions, Boggs et al. (28) have found that clusterin protects against Aβ1–40 toxicity. Although the mechanism of ADDL formation is not yet understood, this discrepancy can be explained by hypothesizing that clusterin retards the formation of fibrils from both Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 solutions. When fibril formation is slowed in Aβ1–42 solutions, however, semistable oligomers (ADDLs) still form, driven presumably by the more hydrophobic C-terminus. Aβ1–40 also can form oligomers, but these are not stable unless crosslinked (54). Thus, retardation of fibril formation by clusterin causes opposite effects on toxicity, depending on the stability of the Aβ oligomeric species. Differential reduction in the rate of fibril formation relative to oligomerization may also play a role in the abilities of cold temperature or low Aβ concentrations to induce ADDLs.

The size and solubility of ADDLs are consistent with their selective ligand-like properties. As demonstrated by trypsin-induced loss of binding sites, ADDLs bind only to particular domains of cell surface proteins. Patchy distribution of ADDL binding sites observed by immunofluorescence microscopy (M.P.L., A.K.B., C.E.F., G.A., and W.L.K., unpublished data) and the absence of ADDL binding to yeast cells (Fig. 3) also indicate binding is selective. Initial tests to compare ADDL binding sites with the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) indicate no overlap (M.P.L. et al., unpublished data), consistent with reports that RAGE accounts for only 60% of the Aβ associated with neurons (38). Fucoidin, an antagonist for scavenger receptors (SR; ref. 55), blocks ADDL binding to B103 cells (M.P.L. et al., unpublished data). Supposedly, SRs are not on neurons, suggesting a possible neuronal SR-like receptor for ADDLs. That ADDL toxicity required cell surface binding was indicated by the neuroprotective effect of cell surface tryptic peptides, which also acted as binding antagonists (Fig. 3).

The sequence of events downstream from ADDL binding is not known. However, ADDL toxicity was found to depend on expression of Fyn, a protein tyrosine kinase of the Src family. Slices from Fyn knockout animals were completely protected against ADDL toxicity (Fig. 4). The dependence of ADDL-evoked cell death on Fyn is especially intriguing because of elevated Fyn immunoreactivity reported for PHF-1 positive neurons in AD-afflicted brain tissue (28). Src family kinases are germane to multiple transduction pathways (40, 56), and Fyn knockout animals previously were found to exhibit reduced neuronal apoptosis in the developing hippocampus (42). Although the basis for neuroprotection by Fyn knockout is unknown, the effect is selective, as NMDA agonists remain highly potent neurotoxins in Fyn knockout animals (data not shown). Because NMDA receptor antagonists also did not inhibit ADDL toxicity (M.P.L. et al., unpublished data), it is likely that ADDL-evoked cell death is not mediated indirectly by NMDA receptors. Theoretically, Fyn could be a downstream effector of either Ca2+ or reactive oxygen species (ROS), which have been implicated in cell death caused by conventional Aβ preparations (57–59). Previous studies in nonneuronal cells have shown that both Ca2+ and ROS are relevant to signaling via Src family protein tyrosine kinases (59–61). In neuronal cells, toxicity of traditional Aβ preparations also has been linked to transduction molecules associated with focal contact signaling (32, 62, 63), a cascade that includes Fyn (41). In B103 cells, ADDLs have been found to stimulate Fyn kinase ≈2-fold within 30 min (C.Z. and W.L.K., unpublished data). Ectopic stimulation of Fyn activity, which can be mitogenic (64), potentially could lead to nerve cell death via mitotic catastrophe. The idea that unbalanced mitogenic signaling can trigger cell death has had increasing support, including data from neuronal systems (65). The recent finding that AD brain has ectopically expressed cell cycle proteins (67) indicates that this hypothesis is potentially viable for AD.

In addition to evoking Fyn-dependent nerve cell death, ADDLs also inhibit LTP, a classic model for synaptic plasticity. Of particular significance, this inhibition is extremely rapid; after only 45 min, ADDLs completely block LTP in brain slices (Fig. 5). Preliminary experiments also show this rapid effect by using LTP assays in vivo (M.P.L. et al., unpublished data). Conceivably, the ADDL effect could be related to disruption of Fyn signaling. In Fyn knockout mice, LTP is abnormal (42), but in animals with Fyn restored postnatally, LTP is improved, indicating the electrophysiological effect of Fyn knockout is not developmental (66). The inhibition of LTP by ADDLs is not caused by cell death, because at 45 min there are no signs of overt cytodegeneration; moreover, cells are electrophysiologically active, albeit lacking in LTP. ADDLs thus have profound neurological effects well in advance of tissue damage. If Aβ derivatives such as ADDLs prove to be part of Alzheimer’s pathogenesis, these results suggest that it would be theoretically feasible to halt or reverse the disease during its early stages. The particular cell surface proteins and signal transduction molecules that mediate ADDL toxicity would be important targets for drug-based therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to W.L.K., G.A.K., and C.E.F., and from the Boothroyd and Buehler Foundations and the Alzheimer’s Association to W.L.K.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; Aβ, amyloid β peptide; ADDL, Aβ-derived diffusible ligand; LTP, long term potentiation; CNS, central nervous system; AFM, atomic force microscopy; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; DG, stratum granulosum.

To whom reprint requests should be addressed. e-mail: wklein@nwu.edu.

References

- 1.Price D L. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:489–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sisodia S S, Price D J. FASEB J. 1995;9:366–370. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.5.7896005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yankner B A, Duffy L K, Kirschner D A. Science. 1990;250:279–282. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pike C J, Walencewicz A J, Glabe C G, Cotman C W. Brain Res. 1991;563:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91553-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pike C J, Burdick D, Walencewicz A J, Glabe C G, Cotman C W. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1676–1687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01676.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarrett J T, Berger E P, Lansbury P T., Jr Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder S W, Ladror U S, Wade W S, Wang G T, Barrett L W, Matayoshi E D, Krafft G A, Holzman T F. Biophys J. 1994;67:1216–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80591-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selkoe D J. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:373–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, et al. Nat Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki N, Cheung T T, Cai X D, Odaka A, Otvos L, Jr, Eckman C, Golde T E, Younkin S G. Science. 1994;264:1336–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.8191290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmechel D E, Saunders A M, Strittmatter W J, Crain B J, Hulette C M, Joo S H, Pericak-Vance M A, Goldgaber D, Roses A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9649–9653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran P M, Higgins L S, Cordell B, Moser P C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5341–5345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsiao K K, Borchelt D R, Olson K, Johannsdottir R, Kitt C, et al. Neuron. 1995;15:1203–1218. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marx J. Science. 1992;257:1336–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.1529329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickson D W, Yen S H. Neurobiol Aging. 1989;10:402–404. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(89)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terry R D, Masliah E, Salmon D P, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, Katzman R. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:572–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Esch F, Lee M, Dovey H, et al. Nature (London) 1992;359:325–327. doi: 10.1038/359325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oda T, Pasinetti G M, Osterberg H H, Anderson C, Johnson S A, Finch C E. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:1131–1136. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oda T, Wals P, Osterburg H H, Johnson S A, Pasinetti G M, et al. Exp Neurol. 1995;136:22–31. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenzo A, Yankner B A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12243–12247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howlett D R, Jennings K H, Lee D C, Clark M S, Brown F, Wetzel R, Wood S J, Camilleri P, Roberts G W. Neurodegeneration. 1995;4:23–32. doi: 10.1006/neur.1995.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham C R, Shirahama T, Potter H. Neurobiol Aging. 1990;11:123–129. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leveugle B, Scanameo A, Ding W, Fillit H. NeuroReport. 1994;5:1389–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGeer P L, Kawamata T, Walker D G. Brain Res. 1992;579:337–341. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90071-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strittmatter W J, Saunders A M, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Roses A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strittmatter W J, Weisgraber K H, Huang D Y, Dong L M, Salvesen G S, Schmechel D, Saunders A M, Goldgaber D, Roses A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8098–8102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boggs L N, Fuson K S, Baez M, Churgay L, McClure D, Becker G, May P C. J Neurochem. 1997;67:1324–1327. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67031324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirazi S K, Wood J G. NeuroReport. 1993;4:435–437. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199304000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert M P, Stevens G, Sabo S, Barber K, Wang G, Wade W, Krafft G, Holzman T F, Klein W L. J Neurosci Res. 1994;39:377–385. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stine W B, Jr, Snyder S W, Ladror U S, Wade W S, Miller M F, Perun T J, Krafft G A. J Protein Chem. 1996;15:193–203. doi: 10.1007/BF01887400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C, Lambert M P, Bunch C, Barber K, Wade W S, Krafft G A, Klein W L. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25247–25250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. Anal Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stoppini L, Buchs P-A, Muller D. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schubert D, Heinemann S, Carlisle W, Tarikas H, Kimes B, Patrick J, Steinbach J H, Culp W, Brandt B L. Nature (London) 1974;249:224–227. doi: 10.1038/249224a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trommer B L, Kennelly J J, Colley P A, Overstreet L S, Slater N T, Pasternak J F. Exp Neurol. 1995;131:83–92. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens G R, Zhang C, Berg M M, Lambert M P, Barber K, Cantallops I, Routtenberg A, Klein W L. J Neurosci Res. 1996;46:445–455. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19961115)46:4<445::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan S D, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu H, et al. Nature (London) 1996;382:685–691. doi: 10.1038/382685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El Khoury J, Hickman SE, Thomas C A, Cao L, Silverstein S, Loike J D. Nature (London) 1996;382:716–719. doi: 10.1038/382716a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke E A, Brugge J S. Science. 1995;268:233–238. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang C, Qui H E, Krafft G A, Klein W L. Neurosci Lett. 1996;211:187–190. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant S G, O’Dell T J, Karl K A, Stein P L, Soriano P, Kandel E R. Science. 1992;258:1903–1910. doi: 10.1126/science.1361685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruce A J, Sakhi S, Schreiber S S, Baudry M. Exp Neurol. 1995;132:209–219. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vornov J J, Coyle J T. J Neurochem. 1991;56:996–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghiso J, Matsubara E, Koudinov A, Choi-Miura N H, Tomita M, Wisniewski T, Frangione B. Biochem J. 1993;293:27–30. doi: 10.1042/bj2930027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frangione, B., Wisniewski, T. & Ghiso, J. (1994) Neurobiol. Aging 15 Suppl 2, S97–S99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Matsubara E, Soto C, Governale S, Frangione B, Ghiso J. Biochem J. 1996;316:671–679. doi: 10.1042/bj3160671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zlokovic B V, Martel C L, Matsubara E, McComb J G, Zheng G, McCluskey RT, Frangione B, Ghiso J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4229–4234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.May P C, Lampert-Etchells M, Johnson S A, Poirier J, Masters J N, Finch C E. Neuron. 1990;5:831–839. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90342-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuo Y M, Emmerling M R, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Kasunic T C, Kirkpatrick J B, Murdoch G H, Ball M J, Roher A E. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4077–4081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teller J K, Russo C, DeBusk L M, Angelini G, Zaccheo D, et al. Nat Med. 1996;2:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Podlisny M B, Ostaszewski B L, Squazzo S L, Koo E H, Rydell R E, Teplow D B, Selkoe D J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9564–9570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xia W, Zhang J, Kholodenko D, Citron M, Podlisny M B, et al. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7977–7982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levine H. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:755–764. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00052-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krieger M, Herz J. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:601–637. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erpel T, Courtneidge S A. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:176–182. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mattson M P, Cheng B, Davis D, Bryant K, Lieberburg I, Rydel R E. J Neurosci. 1992;12:376–389. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mattson M P, Tomaselli K J, Rydel R E. Brain Res. 1993;621:35–49. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McDonald D R, Brunden K R, Landreth G E. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2284–2294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02284.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Archuleta M M, Schieven G L, Ledbetter J A, Deanin G G, Burchiel S W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6105–6109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calautti E, Missero C, Stein P L, Ezzell R M, Dotto G P. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2279–2291. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang C, Qiu H E, Krafft G A, Klein W L. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berg M M, Krafft G A, Klein W L. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:979–989. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971215)50:6<979::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davidson D, Fournel M, Veilette A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10956–10963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herrup K, Busser J C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:2385–2395. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koijma H, Wang J, Mansuy I M, Grant S G N, Mayford M, Kandel E R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4761–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Busser J, Geldmacher D S, Herrup K. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2801–2807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02801.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]