Abstract

Objective To compare the reporting of essential applicability data from randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies evaluating four new orthopaedic surgical procedures.

Data sources Medline and the Cochrane central register of controlled trials.

Study selection All articles of comparative studies assessing total hip or knee arthroplasty carried out by a minimally invasive approach or computer assisted navigation system.

Data extraction Items judged to be essential for interpreting the applicability of findings about such procedures were identified by a survey of a sample of orthopaedic surgeons (77 of 512 completed the survey). Reports were evaluated for data describing these “essential” items and the number of centres and surgeons involved in the trials. When data on the number of centres and surgeons were not reported, the corresponding author of the selected trials was contacted.

Results 84 articles were identified (38 randomised controlled trials, 46 non-randomised studies). The median percentage (interquartile range) of essential items reported for non-randomised studies compared with randomised controlled trials was 38% (25-63%) versus 44% (38-45%) for items about patients, 71% (43-86%) versus 71% (57-86%) for items considered essential for all interventions, and 38% (25-50%) versus 50% (25-50%) for items about the context of care. More than 80% of both study types were single centre studies, with one or two participating surgeons.

Conclusion The reporting of data related to the applicability of results was poor in published articles of both non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials and did not differ by study design. The applicability of results from the trials and studies was similar in terms of number of centres and surgeons involved and the reproducibility of the intervention.

Introduction

Randomised controlled trials provide the most reliable evidence for quantifying treatment effect sizes.1 2 In the specialty of surgery, however, results of such trials are often criticised for being poorly applicable. The results of non-randomised studies are believed to have better applicability.3 4 5 6 7 8

Applicability (also called external validity or generalisability)9 concerns a multidimensional concept depending on the extent to which participants, the context of care, and the interventions (and comparators) evaluated in studies are representative of, or can be reproduced in, usual care. The applicability of a trial’s results could be limited if patients represent only a small proportion of those being treated in normal practice.10 The participation of centres with different resources and surgeons with different skills may mean that treatment effects observed in research may not be applicable, or at worst are irrelevant, to non-research settings.11 12 13 14 15 Surgical procedures are complex interventions that can be difficult to describe, standardise, and reproduce consistently in clinical practice.16

Appraising the applicability of the results of a study is intertwined with the quality of reporting—that is, the extent to which an article provides information about the patients, the intervention, and the context of care (centres and surgeons’ expertise). Articles often omit important details. Poor reporting of applicability data by researchers may be a barrier to applying research findings in clinical practice.

We tested empirically the hypothesis that non-randomised studies yield results that are more applicable than those of randomised controlled trials. For this purpose we identified items considered by surgeons to be essential for appraising applicability in research articles, compared the reporting of these data in published articles of randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies, and compared the context of care (number of centres and surgeons involved) in published reports of randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies.

We focused on minimally invasive and computer assisted navigation techniques for total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty. These surgical procedures were chosen because they have been developed recently, are complex, and their success depends on patient selection, surgeon experience, and volume of procedures undertaken by a centre.12

Methods

We identified and selected eligible published articles of randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies that assessed four surgical procedures: minimally invasive and computer assisted navigation techniques for total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty. Next, we surveyed orthopaedic surgeons to identify items considered essential in assessing the applicability of evidence for these procedures to clinical practice. We extracted data on the reporting of essential applicability items using standardised methods and compared the quality of reporting for non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials. Finally, we extracted data on the context of care (number of centres and surgeons involved) and compared the applicability of the context of care for non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials.

Search for and selection of eligible studies

We searched for all English language articles of trials that evaluated minimally invasive or computer assisted total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty in Medline and the Cochrane central register of controlled trials (see web extra appendix 1 for details of the search strategy). One author (LP) screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved citations to select the relevant articles. The a priori inclusion criteria were all randomised and non-randomised studies that compared total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty done by a minimally invasive approach or a computer assisted navigation system with one or more conventional procedures. We also included trials that evaluated minimally invasive procedures involving computer assisted navigation techniques.

A priori exclusion criteria were uncontrolled studies, non-therapeutic studies (in vitro, biomechanical, and epidemiological studies), pathophysiological studies, letters, ancillary studies such as a subgroup analysis, studies that compared two minimally invasive procedures or two computer assisted navigation procedures, cost effectiveness evaluations, and systematic reviews or meta-analyses. We also excluded studies that assessed the organisation of the healthcare system or interventions provided to care providers. When more than one article was retrieved for the same study, we considered only the earliest publication as eligible.

We used a standardised form to extract data for each eligible study (see web extra appendix 2): year of publication, type of surgical procedure (total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty, minimally invasive or navigation procedure), study design (randomised controlled trial, non-randomised historically controlled study, case-control study, or other non-randomised comparative study), sample size, whether a statistician or methodologist was included among the authors, the risk of bias, and items essential to interpreting the applicability of the findings.

Identification of items essential for interpreting applicability

To identify items relevant to applicability, we carried out a literature search, relying especially on criteria proposed by the CONSORT statement and its extension for non-pharmacological treatments17 18 and by Rothwell et al.8 Selected items (see web extra appendix 3) were classified into three main domains: the description of the patients, the description of the experimental intervention (for practical reasons we did not focus on the description of the comparator), and the context of care (centres and care providers).

In a second step we invited by email experts to participate in a web based survey: all corresponding authors of published articles of studies (with no restriction on the design) that assessed knee arthroplasty or hip arthroplasty identified by an electronic search strategy (see web extra appendix 4) and all members of the French Hip and Knee Society (SFHG, created in 1997 and consisting of 100 orthopaedic surgeons specialising in hip and knee surgery). For each item, surgeons had to indicate whether they agreed, on a scale of 1 (totally disagree) to 9 (totally agree), that the item should be reported in a published article of a trial. Surgeons could also indicate any other items that were not listed but were deemed important. The criterion used to classify an item as being “essential” for adequate appraisal of the applicability of the published results of a study was a score of 7 or more by 50% or more of respondents.

We did not invite other important stakeholders such as patients or policymakers because surgeons are usually the first line in appraising to whom and in which context trial results should be applied.

Extracting data on essential applicability items

One author (LP) appraised the reporting of essential applicability items using a standardised data extraction form (see web extra appendix 2). The author also assessed whether applicability was considered in the discussion section. A random sample of 15% of the selected articles was reviewed independently by another author (IB) for quality assurance (see web extra appendix 5 for the proportion of agreement between the two reviewers). Items with a low level of agreement were discussed and, if necessary, all selected articles were reappraised after discussion.

We calculated the proportion of essential items reported for three components of applicability: description of the patients, description of the experimental intervention, and context of care.

Context of care

As well as evaluating the reporting of applicability data, we aimed to appraise the actual applicability of the results of the selected trials. Because appraising the applicability of published results of a study is difficult, we focused on only some components related to the context of care—the number of centres and number of surgeons involved in the randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies, assuming that studies with a low number of participating centres and surgeons had low applicability. When the number of centres and participating surgeons was not reported in selected articles, we contacted the corresponding author by email for this information. When authors did not respond we assumed that the number of centres corresponded to the number of orthopaedic centres reported in the affiliations of the article, and the number of surgeons was treated as missing.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are described with frequencies and percentages, and quantitative variables with medians (interquartile ranges).

To compare the reporting of applicability of the results of the two study types, we calculated the percentage of applicability items reported, from 0 (no item reported) to 100 (all items reported), for each trial for the three domains of patients, experimental intervention, and context of care. We compared the percentage of applicability items reported for randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies by a non-paired Wilcoxon test. The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

Applicability assessments are described with frequencies and percentages. All data analyses were done using the R 2.8.0 software package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

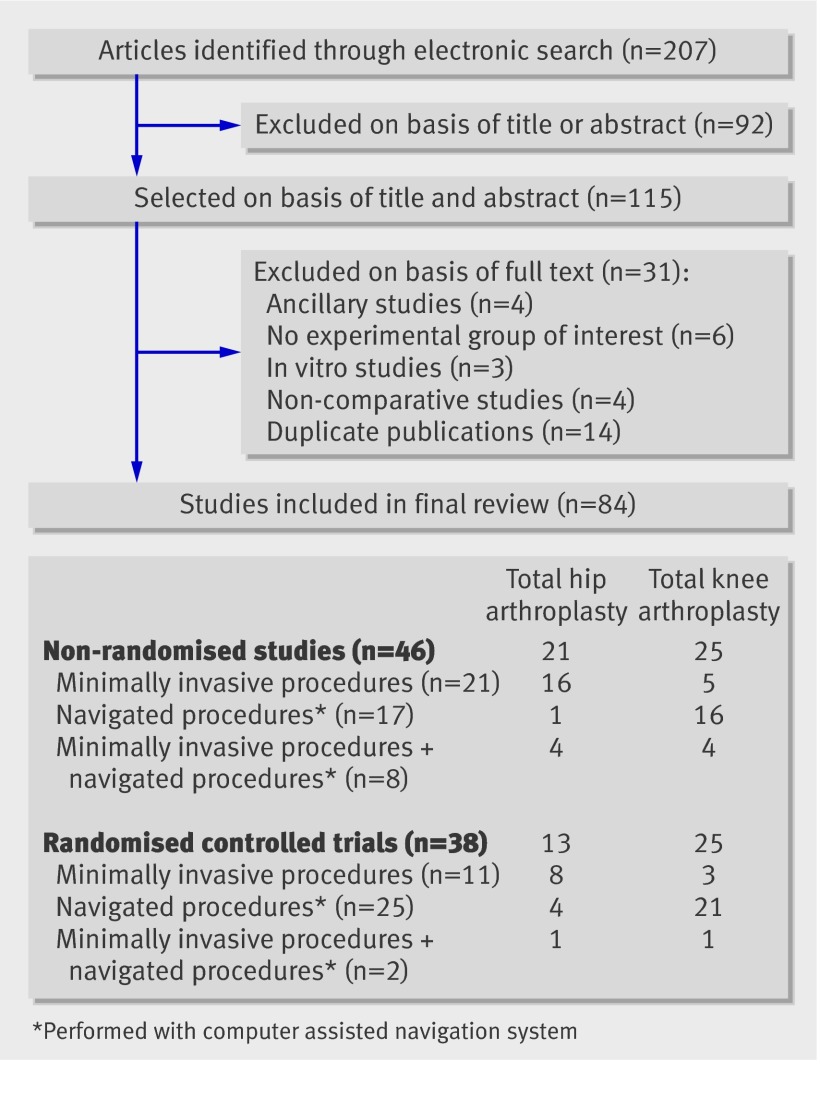

The search strategy generated 207 articles: 84 were eligible and appraised (fig 1). Thirty eight studies were randomised controlled trials and 46 were non-randomised studies. Thirty four studies assessed total hip arthroplasty and 50 total knee arthroplasty. The experimental procedure was a minimally invasive one in 32 studies, a computer assisted navigation technique in 42, and a computer assisted navigation technique associated with a minimally invasive procedure in 10.

Fig 1 Flow of selected articles through study

Characteristics of selected studies

Table 1 details the general characteristics of the selected articles. Articles were published between 2001 and 2008, with the highest number of publications in 2005 and 2006.

Table 1.

Characteristics of reports of non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials

| Characteristics | Reports of non-randomised studies (n=46) | Reports of randomised controlled trials (n=38) |

|---|---|---|

| Median sample size (interquartile range): | ||

| No of patients | 92 (60-131) | 90 (60-120) |

| No of hips or knees undergoing surgery | 90 (78-132) | 95 (60-148) |

| Designs of non-randomised studies: | ||

| Controlled cohort | 30 (65) | — |

| Historically controlled | 14 (30) | — |

| Case-control | 2 (4) | — |

| Justification for absence of randomisation | 2 (4) | — |

| Main outcome reported | 18 (39) | 23 (61) |

| Radiographic findings (for example, implant positioning)* | 17 (94) | 20 (87) |

| Length of follow-up (months): | ||

| Not reported | 10 (22) | 7 (18) |

| ≤3 | 15 (33) | 20 (53) |

| 3-6 | 6 (13) | 5 (13) |

| 6-12 | 9 (20) | 1 (3) |

| 12-24 | 4 (9) | 3 (8) |

| >24 | 2 (4) | 2 (5) |

| Patients’ selection bias | ||

| Non-randomised studies: | ||

| Patients recruited from same population | 20 (44) | — |

| Consecutive series of patients grouped | 16 (35) | — |

| Attempts to balance groups by design (matching) | 15 (33) | — |

| Randomised controlled trials: | ||

| Generation of allocation sequence reported and adequate | — | 18 (47) |

| Treatment allocation concealment reported and adequate | — | 0 |

| Groups comparable at baseline | 32 (70) | 33 (87) |

| Analysis adjusted for important confounders | 1 (2) | 3 (7.9) |

| Evaluation bias | ||

| Blinded outcome assessor | 15 (33) | 19 (50) |

| Independent outcome assessor (when not blinded) | 11 (24) | 5 (13) |

| Monitoring procedure reported | 0 | 4 (11) |

| Attrition bias | ||

| All patients analysed | 6 (13) | 8 (21) |

| Rate of missing data reported | 1 (2) | 2 (5) |

| Methods to handle missing data reported | 0 | 0 |

*Occurrence of radiographic main outcomes over all types of main outcomes.

The median (interquartile range) number of patients for non-randomised studies was 92 (60-131) and for randomised controlled trials was 90 (60-120). Thirty (65%) non-randomised studies were controlled cohort studies, 14 (30%) historically controlled studies, and 2 (4%) case-control studies. Eleven (37%) controlled cohort studies were clearly reported as being prospective. The comparator was systematically another surgical procedure.

A primary outcome was clearly reported for 39% of non-randomised studies (n=18) and 61% of randomised controlled trials (n=23) and, when reported, was radiographic in 93% of reports (n=37). The duration of follow-up, when reported, was no longer than one year in 84% (56/67) of the articles. Adverse events were reported for 70% of non-randomised studies (n=32) and 61% of randomised controlled trials (n=23). A definition of severe adverse events was given in the reports of only three non-randomised studies (7%) and two randomised controlled trials (5%).

Survey of surgeons

Of the 512 experts contacted by email, 87 completed the web based survey. Respondents who were not orthopaedic surgeons (n=10) were excluded (see web extra appendix 6 for the flow of experts and web extra appendix 7 for a description of these participants). The results of the survey are summarised in web extra appendix 8. Eight items were classified as essential for patient characteristics and four for context of care (centres and surgeons). These items did not differ according to the procedure evaluated. Essential items describing the intervention varied by procedure: seven generic items were selected for all of the interventions (minimally invasive and computer navigated total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty) and nine items were selected specifically for minimally invasive procedures and seven for navigated procedures.

Reporting of essential applicability items

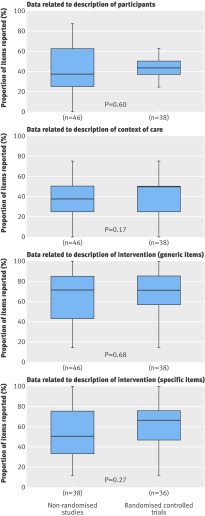

Tables 2 and 3 and figure 2 describe the reporting of essential applicability items.

Table 2.

Reporting of essential applicability items*. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Variables reported | All reports (n=84) | Reports of non-randomised studies (n=46) | Reports of randomised controlled trials (n=38) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline clinical characteristics of patients: | 77 (92) | 40 (87) | 37 (98) |

| Age | 74 (88) | 38 (83) | 36 (95) |

| Sex | 68 (81) | 34 (74) | 34 (90) |

| Body mass index | 50 (60) | 23 (50) | 27 (71) |

| Underlying disease for THA or TKA indication | 43 (51) | 27 (59) | 16 (42) |

| Functional status | 25 (30) | 14 (30) | 11 (29) |

| Preoperative pain | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (5) |

| Patient’s preoperative deformity | 14 (17) | 10 (22) | 4 (11) |

| Comorbidities | 14 (17) | 6 (13) | 8 (21) |

| Setting and centre: | |||

| No of centres | 35 (42) | 16 (35) | 19 (50) |

| Centres’ surgical volume | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 |

| No of surgeons | 68 (81) | 37 (80) | 31 (82) |

| Data on surgeons’ experience | 35 (42) | 16 (59) | 19 (50) |

| Generic items selected for all interventions: | |||

| Surgical approach | 56 (67) | 30 (65) | 26 (68) |

| Duration of intervention | 58 (69) | 30 (65) | 28 (74) |

| Prosthesis implanted | 67 (80) | 33 (72) | 34 (90) |

| Brand name of prosthesis | 66 (79) | 33 (72) | 33 (87) |

| Type of fixation | 58 (69) | 30 (65) | 28 (74) |

| Rehabilitation programme | 29 (35) | 17 (37) | 12 (32) |

| Length of hospital stay | 24 (29) | 15 (33) | 9 (24) |

THA=total hip arthroplasty; TKA=total knee arthroplasty.

*More than 50% of respondents rated these items as 7 or more on 0-9 scale in survey of sample of surgeons.

Table 3.

Reporting of essential items describing intervention specific to procedure evaluated*. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Variables reported | All reports | Reports of non-randomised studies | Reports of randomised controlled trials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Items selected for minimally invasive procedures: | n=32 | n=21 | n=11 |

| Information provided to patients | 3 (9) | 1 (5) | 2 (18) |

| Preoperative care | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (9) |

| Anaesthesia protocol | 11 (34) | 7 (64) | 4 (36) |

| Thromboprophylaxis protocol | 6 (19) | 5 (24) | 1 (9) |

| Length of incision | 26 (81) | 17 (81) | 9 (82) |

| Description of instrumentation† used in minimally invasive procedures | 22 (69) | 15(71) | 7 (64) |

| Postoperative pain management protocol | 8 (25) | 4 (19) | 4 (36) |

| Blood loss‡ | 22/24 (92) | 15/16 (94) | 7/8 (88) |

| Antibioprophylaxis protocol‡ | 3/24 (13) | 2/16 (13) | 1/8 (13) |

| Items selected for computer assisted navigation procedures: | n=42 | n=17 | n=25 |

| Description of navigation system | 41 (98) | 17 (100) | 24 (96) |

| Brand name of navigation system | 41 (98) | 17 (100) | 24 (96) |

| Type of navigation system (image based or imageless) | 35 (83) | 15 (88) | 20/26 (7) |

| Characteristics of navigation system (open or closed) | 2 (5) | 1 (6) | 1/26 (4) |

| Blood loss§ | 2/5 | 0/1 | 2/4 |

| Postoperative pain management protocol§ | 0/5 | 0/1 | 0/4 |

Reports of trials assessing minimally invasive navigated procedures were excluded: non-randomised studies (n=4) and randomised controlled trials for total hip arthroplasty (n=1) and total knee arthroplasty (n=1).

*More than 50% of respondents rated these items 7 or more on 0-9 scale in survey of sample of surgeons).

†Standard or specific.

‡Only for minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty (n=24).

§Only for computer assisted total hip arthroplasty (n=5).

Fig 2 Proportion of essential items (rated ≥7 on 0-9 scale by >50% of surgeons) reported by non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials. Minimally invasive navigated procedures were excluded (n=10) because relevance of items for interventions were selected for minimally invasive or navigated technique. Solid line is median of distribution, and upper and lower ends of box are upper and lower quartiles of data. Whiskers extend to most extreme values within 1.5 times interquartile range

The median proportion (interquartile range) of essential items for non-randomised studies and for randomised controlled trials for the description of participants was 38% (25-63%) and 44% (38-45%; P=0.60), for the description of the experimental intervention was 71% (43-86%) and 71% (57-86%; P=0.68), for the generic items was 50% (33-75%), and for specific items was 67% (49-75%; P=0.27).

The median proportion (interquartile range) of essential items describing the context of care for non-randomised studies and for randomised controlled trials was 38% (25-50%) and 50% (25-50%; P=0.17). The number of centres reported for non-randomised studies was 35% (n=16) and for randomised controlled trials was 50% (n=19). Details such as volume of care in the centre were reported for only two non-randomised studies (4%). Details on surgeons’ expertise were reported for 59% of non-randomised studies (n=16) and 50% of randomised controlled trials (n=19). When reported, these details described years of practice for only one non-randomised comparative study (6%) and one randomised controlled trial (5%) and the number of experimental interventions carried out before the start of the study for 50% of non-randomised studies (n=8) and 55% of randomised controlled trials (n=11). For 38% of non-randomised studies (n=6) and 30% of randomised controlled trials (n=6) the surgeons were reported as “experts,” without any further detail.

Finally, issues with applicability were discussed in the discussion section of 22% of the articles of non-randomised studies (n=10) and 21% of those of randomised controlled trials (n=8).

Context of care

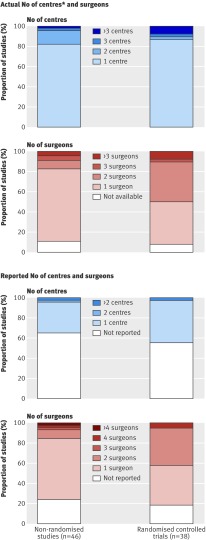

The context of care was evaluated by comparing the number of surgeons and centres involved in the randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies. After we contacted the corresponding authors, the number of participating surgeons was known for 81% of the studies (n=68). Data on the number of centres were available for 58 studies (69%). For the remaining 26 studies, the number of orthopaedic centres reported in the affiliations was considered.

Figure 3 describes the reported and actual number of participating centres and surgeons in the trials. The actual number of centres did not differ according to study design because most trials were carried out in only one centre: 82% of non-randomised studies (n=37) and 87% of randomised controlled trials (n=33). The actual number of participating surgeons was comparable between the two study types. One or two surgeons participated in 80% of the non-randomised studies (n=37) and in 82% of the randomised controlled trials (n=31).

Fig 3 Number of participating centres and surgeons in randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies assessing minimally invasive technique and computer assisted navigated technique for total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty. *When number of centres was not reported in text or available from author then number of centres reported in affiliations was chosen

Discussion

Our appraisal of 84 articles of non-randomised studies (n=46) and randomised controlled trials (n=38) that assessed four orthopaedic interventions (total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty carried out by a minimally invasive approach or computer assisted navigation system) does not support the hypothesis that, in general, results of non-randomised studies have better applicability than those of randomised controlled trials. The reporting of items judged “essential” for determining applicability did not differ between the two study designs. Important components of the intervention itself, such as protocols for preoperative care or management of pain, were rarely described. The proxy used to evaluate the applicability related to the context of care—the number of surgeons and centres—was similar between the trial types as well. Other factors potentially affecting actual applicability, such as the relevance of a radiographic primary outcome and duration of follow-up of less than one year, also did not differ by study design and limited the applicability of the results of the selected studies. Our results suggest that some reports of both non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials may be of uncertain value to surgeons, researchers, systematic reviewers, and decision makers.

These results inevitably prompt the question of why. Controlled studies in other healthcare specialties vary on a spectrum of “pragmatism” or “efficacy/effectiveness,” addressing research questions focused on clinical or policy decisions or mechanisms of action.19 Are our findings evidence of general disinterest among surgeons about pragmatic questions or were the interventions reviewed here too new? Some examples of nationally representative studies on surgical outcomes, such as those involving national arthroplasty registers, may provide useful data, but such studies make up a tiny fraction of the surgical literature. In fact, no published articles evaluating the selected procedures used data from a national register or similar database with wide coverage. Furthermore, studies carried out in other specialties highlight the challenges of interpreting the findings of non-randomised studies involving a nationally representative sample.20 21

How could we improve the situation? Applicability must be considered as it is usually done for internal validity at different steps of the trial: in the protocol, when deciding the eligibility criteria for the centres, surgeons, and patients but also when reporting the trial results by following the CONSORT statement,22 particularly the extension for non-pharmacological treatments.17 To tackle the question of the impact of the surgical learning curve, for instance, one author recommended that “surgical trials should report explicitly and informatively on the prior expertise of the participating surgeons.”23

Our results on applicability reporting are consistent with those for other trials, highlighting that authors pay insufficient attention to applicability in their published articles of randomised controlled trials.8 24 However, to our knowledge this is the first study to compare the reporting of applicability data in reports of randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies. Furthermore, we took into account that applicability criteria vary depending on the procedure evaluated. In our study, orthopaedic surgeons contributed to the selection of relevant applicability items for each of the four interventions.

Limitations of the study

The study has several limitations. Firstly, we focused on studies assessing the specific procedures of total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty, and these results should be confirmed in other surgical areas. However, we chose recent interventions that are increasingly being used in clinical practice. This choice also allowed for a detailed and precise assessment of applicability. Secondly, we focused on the reporting of essential applicability information for randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies and evaluated the actual applicability of the results of the studies mainly from data related to the context of care. We were unable to compare the representativeness of patients in reports of both study designs because essential information was often missing. Thirdly, for practical reasons we evaluated the context of care by focusing only on the centres and surgeons. Finally, we assumed that involvement of more centres and surgeons implies better applicability of results, but this assumption is not true when all participating centres and surgeons have high expertise. However, our results highlighted that most trials involved only one centre and one or two surgeons, and the applicability of results from such trials is probably debatable.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study highlights the poor reporting of data related to the applicability and generalisability of results in published articles of both non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials. Furthermore, the appraisal of the applicability of results from the two trial types did not differ in terms of number and expertise of centres and surgeons involved and the reproducibility of the intervention. From these articles we were unable to conclude whether the patients who participated were representative. The results of this study need confirmation in other disciplines.

What is already known on this topic

In the specialty of surgery, results from randomised controlled trials are criticised for having poor applicability to clinical practice

This argument is often used to justify the use of observational studies rather than randomised controlled trials

What this study adds

Our results do not support the hypothesis that results from non-randomised studies of surgery have better applicability than those from randomised controlled trials

The reporting of applicability data was poor with both designs

Both study types were mainly single centre studies, with one or two participating surgeons

We thank the experts who completed the online survey: J N Argenson, J N Auyeung, T Baad-Hansen, D L Back, A R Barrett, M Bercovy, D Biau, R Bourne, P Boyer, K J Bozic, I J Brenkel, J L Briard, J Bruns, M Buttaro, P Calas, P Cartier, I B De Groot, F H De Man, C Delaunay, L Descamps, R Eisele, R H Emerson Jr, S A Ender, J A Epinette, M C Forster, F Frihagen, R Gandhi, L E Gayet, F Genet, A Gonzalez Della Valle, W L Griffin, R A Hall, M Hamadouche, D Hannouche, D Hernandez-Vaquero, B E Heyworth, C Hulet, C A Jacobs, P K Jaiswal, J Y Jenny, T Judet, R L Kane, V Karatosun, L Kerboull, Y S Kim, S Kohler, P Kort, J M Laffosse, G Lecerf, E A Lingard, S J MacDonald, O M Mahoney, A Martin, D Matlock, T Matsumoto, C W McBryde, H Mizu-Uchi, F D Naal, J M Naylor, R G Nelissen, M A Newman, R Nizard, V Oztuna, R Padua, J Parvizi, M K Petersen, A Phadnis, R Philippot, F Picard, P Piriou, R W Poolman, S Procyk, T A Radcliff, O Robertsson, A R Rochwerger, A Roth, O Sadr Azodi, D Saragaglia, A P Schulz, R J Sierra, J P Simon, M Soubeyrand, L M Specht, M Stevens, F Thorey, I Van den Akker-Scheek, C Vielpeau, R Wagenmakers, P Weinrauch, H Wu, P J Yates, and F Zadegan; Laura Heraty (BioMedEditing East York, ON Canada) who edited the manuscript for submission; and Samira Laribi who designed the website for the survey.

Contributors: LP, IB, BR, and PR conceived and designed the study. LP and IB acquired the data. All authors analysed and interpreted the data. LP drafted the manuscript. IB, BR, RN, and PR critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. PR provided administrative, technical, and material support. All authors saw and approved the final manuscript. LP, IB, and PR are guarantors, had full access to the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: IB is supported by a grant from the Societé Francaise de Rhumatologie and the Lavoisier Program (Ministère des Affaires étrangères et européennes). The Funders were not involved in the conduct of the study or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: The technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b4538

References

- 1.Abel U, Koch A. The role of randomization in clinical studies: myths and beliefs. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:487-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dreyfuss D. Is it better to consent to an RCT or to care? Intensive Care Med 2005;31:345-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook RC, Alscher KT, Hsiang YN. A debate on the value and necessity of clinical trials in surgery. Am J Surg 2003;185:305-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ 1996;312:1215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonell C, Oakley A, Hargreaves J, Strange V, Rees R. Assessment of generalisability in trials of health interventions: suggested framework and systematic review. BMJ 2006;333:346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persaud N, Mamdani MM. External validity: the neglected dimension in evidence ranking. J Eval Clin Pract 2006;12:450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen MK, Andersen KV, Andersen NT, Soballe K. “To whom do the results of this trial apply?” External validity of a randomized controlled trial involving 130 patients scheduled for primary total hip replacement. Acta Orthop 2007;78:12-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?” Lancet 2005;365:82-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dekkers OM, Elm EV, Algra A, Romijn JA, Vandenbroucke JP. How to assess the external validity of therapeutic trials: a conceptual approach. Int J Epidemiol 2009;17:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flather M, Delahunty N, Collinson J. Generalizing results of randomized trials to clinical practice: reliability and cautions. Clin Trials 2006;3:508-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Wright RJ, Losina E. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and the outcomes of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A(9):1909-16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lavernia CJ, Guzman JF. Relationship of surgical volume to short-term mortality, morbidity, and hospital charges in arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1995;10:133-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norton EC, Garfinkel SA, McQuay LJ, Heck DA, Wright JG, Dittus R, et al. The effect of hospital volume on the in-hospital complication rate in knee replacement patients. Health Serv Res 1998;33(5 Pt 1):1191-210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2117-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimick JB, Cowan JA Jr, Colletti LM, Upchurch GR Jr. Hospital teaching status and outcomes of complex surgical procedures in the United States. Arch Surg 2004;139:137-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein AM. Volume and outcome—it is time to move ahead. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:295-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med 2007;45:247-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 2008;337:a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves BC, Langham J, Lindsay KW, Molyneux AJ, Browne JP, Copley L, et al. Findings of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial and the National Study of Subarachnoid Haemorrhage in context. Br J Neurosurg 2007;21:318-23; discussion 323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langham J, Reeves BC, Lindsay KW, van der Meulen JH, Kirkpatrick PJ, Gholkar AR, et al. Variation in outcome after subarachnoid haemorrhage: a study of neurosurgical units in UK and Ireland. Stroke 2009;40:111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:663-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook JA. The challenges faced in the design, conduct and analysis of surgical randomised controlled trials. Trials 2009;10:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad N, Boutron I, Moher D, Pitrou I, Roy C, Ravaud P. Neglected external validity in reports of randomized trials: the example of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:361-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]