Abstract

Explanations of psychological phenomena seem to generate more public interest when they contain neuroscientific information. Even irrelevant neuroscience information in an explanation of a psychological phenomenon may interfere with people’s abilities to critically consider the underlying logic of this explanation. We tested this hypothesis by giving naïve adults, students in a neuroscience course, and neuroscience experts brief descriptions of psychological phenomena followed by one of four types of explanation, according to a 2 (good explanation vs. bad explanation) × 2 (without neuroscience vs. with neuroscience) design. Crucially, the neuroscience information was irrelevant to the logic of the explanation, as confirmed by the expert subjects. Subjects in all three groups judged good explanations as more satisfying than bad ones. But subjects in the two nonexpert groups additionally judged that explanations with logically irrelevant neuroscience information were more satisfying than explanations without. The neuroscience information had a particularly striking effect on nonexperts’ judgments of bad explanations, masking otherwise salient problems in these explanations.

INTRODUCTION

Although it is hardly mysterious that members of the public should find psychological research fascinating, this fascination seems particularly acute for findings that were obtained using a neuropsychological measure. Indeed, one can hardly open a newspaper’s science section without seeing a report on a neuroscience discovery or on a new application of neuroscience findings to economics, politics, or law. Research on nonneural cognitive psychology does not seem to pique the public’s interest in the same way, even though the two fields are concerned with similar questions.

The current study investigates one possible reason why members of the public find cognitive neuroscience so particularly alluring. To do so, we rely on one of the functions of neuroscience information in the field of psychology: providing explanations. Because articles in both the popular press and scientific journals often focus on how neuroscientific findings can help to explain human behavior, people’s fascination with cognitive neuroscience can be redescribed as people’s fascination with explanations involving a neuropsychological component.

However, previous research has shown that people have difficulty reasoning about explanations (for reviews, see Keil, 2006; Lombrozo, 2006). For instance, people can be swayed by teleological explanations when these are not warranted, as in cases where a nonteleological process, such as natural selection or erosion, is actually implicated (Lombrozo & Carey, 2006; Kelemen, 1999). People also tend to rate longer explanations as more similar to experts’ explanations (Kikas, 2003), fail to recognize circularity (Rips, 2002), and are quite unaware of the limits of their own abilities to explain a variety of phenomena (Rozenblit & Keil, 2002). In general, people often believe explanations because they find them intuitively satisfying, not because they are accurate (Trout, 2002).

In line with this body of research, we propose that people often find neuroscience information alluring because it interferes with their abilities to judge the quality of the psychological explanations that contain this information. The presence of neuroscience information may be seen as a strong marker of a good explanation, regardless of the actual status of that information within the explanation. That is, something about seeing neuroscience information may encourage people to believe they have received a scientific explanation when they have not. People may therefore uncritically accept any explanation containing neuroscience information, even in cases when the neuroscience information is irrelevant to the logic of the explanation.

To test this hypothesis, we examined people’s judgments of explanations that either do or do not contain neuroscience information, but that otherwise do not differ in content or logic. All three studies reported here used a 2 (explanation type: good vs. bad) × 2 (neuroscience: without vs. with) design. This allowed us to see both people’s baseline abilities to distinguish good psychological explanations from bad psychological explanations as well as any influence of neuroscience information on this ability. If logically irrelevant neuroscience information affects people’s judgments of explanations, this would suggest that people’s fascination with neuropsychological explanations may stem from an inability or unwillingness to critically consider the role that neuroscience information plays in these explanations.

EXPERIMENT 1

Methods

Subjects

There were 81 participants in the study (42 women, 37 men, 2 unreported; mean age = 20.1 years, SD = 4.2 years, range = 18–48 years, based on 71 reported ages). We randomly assigned 40 subjects to the Without Neuroscience condition and 41 to the With Neuroscience condition. Subjects thus saw explanations that either always did or always did not contain neuroscience information. We used this between-subjects design to prevent subjects from directly comparing explanations that did and did not contain neuroscience, providing a stronger test of our hypothesis.

Materials

We wrote descriptions of 18 psychological phenomena (e.g., mutual exclusivity, attentional blink) that were meant to be accessible to a reader untrained in psychology or neuroscience. For each of these items, we created two types of explanations, good and bad, neither of which contained neuroscience. The good explanations in most cases were the genuine explanations that the researchers gave for each phenomenon. The bad explanations were circular restatements of the phenomenon, hence, not explanatory (see Table 1 for a sample item).

Table 1.

Sample Item

| Good Explanation | Bad Explanation | |

|---|---|---|

| Without Neuroscience | The researchers claim that this “curse” happens because subjects have trouble switching their point of view to consider what someone else might know, mistakenly projecting their own knowledge onto others. |

The researchers claim that this “curse” happens because subjects make more mistakes when they have to judge the knowledge of others. People are much better at judging what they themselves know. |

| With Neuroscience |

Brain scans indicate that this “curse” happens because of the frontal lobe brain circuitry known to be involved in self-knowledge. Subjects have trouble switching their point of view to consider what someone else might know, mistakenly projecting their own knowledge onto others. |

Brain scans indicate that this “curse” happens because of the frontal lobe brain circuitry known to be involved in self-knowledge. Subjects make more mistakes when they have to judge the knowledge of others. People are much better at judging what they themselves know. |

Researchers created a list of facts that about 50% of people knew. Subjects in this experiment read the list of facts and had to say which ones they knew. They then had to judge what percentage of other people would know those facts. Researchers found that the subjects responded differently about other people’s knowledge of a fact when the subjects themselves knew that fact. If the subjects did know a fact, they said that an inaccurately large percentage of others would know it, too. For example, if a subject already knew that Hartford was the capital of Connecticut, that subject might say that 80% of people would know this, even though the correct answer is 50%. The researchers call this finding “the curse of knowledge.”

The neuroscience information is highlighted here, but subjects did not see such marking.

For the With Neuroscience conditions, we added neuroscience information to the good and bad explanations from the Without Neuroscience conditions. The added neuroscience information had three important features: (1) It always specified that the area of activation seen in the study was an area already known to be involved in tasks of this type, circumventing the interpretation that the neuroscience information added value to the explanation by localizing the phenomenon. (2) It was always identical or nearly identical in the good explanation and the bad explanation for a given phenomenon. Any general effect of neuroscience information on judgment should thus be seen equally for good explanations and bad explanations. Additionally, any differences that may occur between the good explanation and bad explanation conditions would be highly unlikely to be due to any details of the neuroscience information itself. (3) Most importantly, in no case did the neuroscience information alter the underlying logic of the explanation itself. This allowed us to test the effect of neuroscience information on the task of evaluating explanations, independent of any value added by such information.1 Before the study began, three experienced cognitive neuroscientists confirmed that the neuroscience information did not add value to the explanations.

Procedure

Subjects were told that they would be rating explanations of scientific phenomena, that the studies they would read about were considered solid, replicable research, and that the explanations they would read were not necessarily the real explanations for the phenomena. For each of the 18 stimuli, subjects read a one-paragraph description of the phenomenon followed by an explanation of that phenomenon. They rated how satisfying they found the explanation on a 7-point scale from −3 (very unsatisfying) to +3 (very satisfying) with 0 as the neutral midpoint.

Results and Discussion

Preliminary analyses revealed no differences in performance based on sex or level of education, so ratings were collapsed across these variables for the analyses. Additionally, subjects tended to respond similarly to all 18 items (Cronbach’s α = .79); the set of items had acceptable psychometric reliability as a measure of the construct of interest.

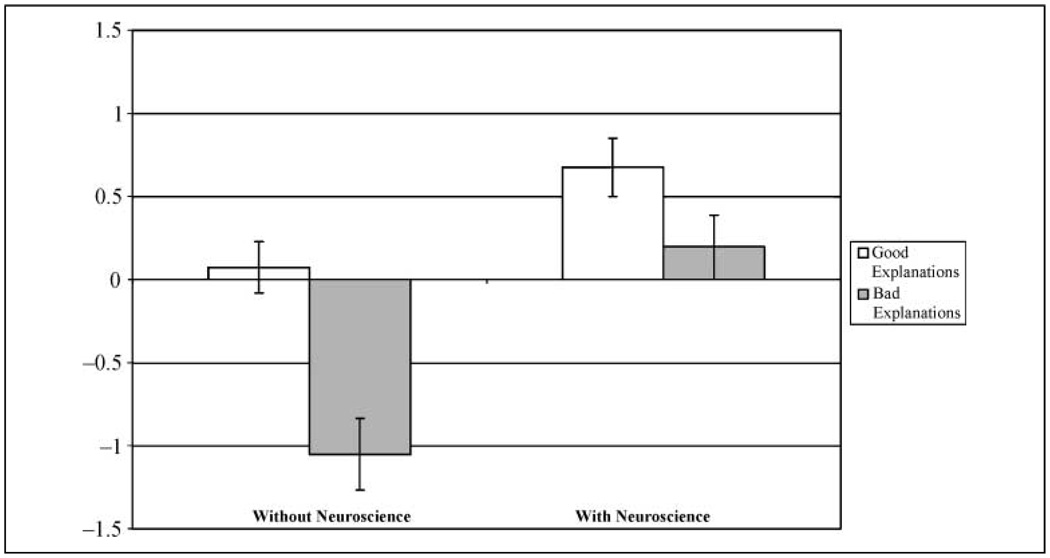

Our primary goal in this study was to discover what effect, if any, the addition of neuroscience information would have on subjects’ ratings of how satisfying they found good and bad explanations. We analyzed the ratings using a 2 (good explanation vs. bad explanation) × 2 (without neuroscience vs. with neuroscience) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Novice group. Mean ratings of how satisfying subjects found the explanations. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

There was a significant main effect of explanation type [F(1, 79) = 144.8, p < .01], showing that good explanations (M = 0.88, SE = 0.10) are rated as significantly more satisfying than bad explanations (M = −0.28, SE = 0.12). That is, subjects were accurate in their assessments of explanations in general, finding good explanations to be better than bad ones.

There was also a significant main effect of neuroscience [F(1, 79) = 6.5, p < .05]. Explanations with neuroscience information (M = 0.53, SE = 0.13) were rated as significantly more satisfying than explanations that did not include neuroscience information (M = 0.06, SE = 0.13). Adding irrelevant neuroscience information thus somehow impairs people’s baseline ability to make judgments about explanations.

We also found a significant interaction between explanation type and neuroscience information [F(1, 79) = 18.8, p < .01]. Post hoc tests revealed that although the ratings for good explanations were not different without neuroscience (M = 0.86, SE = 0.11) than with neuroscience (M = 0.90, SE = 0.16), ratings for bad explanations were significantly lower for explanations without neuroscience (M = −0.73, SE = 0.14) than explanations with neuroscience (M = 0.16, SE = 0.16). Note that this difference is not due to a ceiling effect; ratings of good explanations are still significantly below the top of the scale [t(80) = −21.38, p < .01]. This interaction indicates that it is not the mere presence of verbiage about neuroscience that encourages people to think more favorably of an explanation. Rather, neuroscience information seems to have the specific effect of making bad explanations look significantly more satisfying than they would without neuroscience.

This puzzling differential effect of neuroscience information on the bad explanations may occur because participants gave the explanations a more generous interpretation than we had expected. Our instructions encouraged participants to think of the explanations as being provided by knowledgeable researchers, so they may have considered the explanations less critically than we would have liked. If participants were using somewhat relaxed standards of judgment, then a group of subjects that is specifically trained to be more critical of judging explanations should not fall prey to the effect of added neuroscience information, or at least not as much.

Experiment 2 addresses this issue by testing a group of subjects trained to be critical in their judgments: students in an intermediate-level cognitive neuroscience class. These students were receiving instruction on the basic logic of cognitive neuroscience experiments and on the types of information that are relevant to drawing conclusions from neuroscience studies. We predicted that this instruction, together with their classroom experience of carefully analyzing neuroscience experiments, would eliminate or dampen the impact of the extraneous neuroscience information.

EXPERIMENT 2

Methods

Subjects and Procedure

Twenty-two students (10 women; mean age = 20.7 years, SD = 2.6 years, range = 18–31 years) were recruited from an introductory cognitive neuroscience class and received no compensation for their participation. They were informed that although participation was required for the course, the results of the experiment would have no impact on their class performance and would not be known by their professor until after their grades had been posted. They were additionally allowed to choose whether their data could be used in the published research study, and all students elected to have their data included.

Subjects were tested both at the beginning of the semester and at the end of the semester, prior to the final exam.

The stimuli and task were identical to Experiment 1, with one exception: Both main variables of explanation type and presence of neuroscience were within-subject due to the small number of participants.

Results and Discussion

Preliminary analyses showed no differences in performance based on class year, so this variable is not considered in the main analyses. There was one significant interaction with sex that is discussed shortly. Responses to the items were again acceptably consistent (Cronbach’s α = .74).

As with the novices in Experiment 1, we tested whether the addition of neuroscience information affects judgments of good and bad explanations. For the students in this study, we additionally tested the effect of training on evaluations of neuroscience explanations. We thus analyzed the students’ ratings of explanatory satisfaction using a 2 (good explanation vs. bad explanation) × 2 (without neuroscience vs. with neuroscience) × 2 (preclass test vs. postclass test) repeated measures ANOVA (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Student group. Mean ratings of how satisfying subjects found the explanations. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

We found a significant main effect of explanation type [F(1, 21) = 50.9, p < .01], confirming that the students judged good explanations (M = 0.37, SE = 0.14) to be more satisfying than bad explanations (M = −0.43, SE = 0.19).

Although Experiment 1 found a strong effect of the presence of neuroscience information in explanations, we had hypothesized that students in a neuroscience course, who were learning to be critical consumers of neuroscience information, would not show this effect. However, the data failed to confirm this hypothesis; there was a significant main effect of neuroscience [F(1, 21) = 47.1, p < .01]. Students, like novices, judged that explanations with neuroscience information (M = 0.43, SE = 0.17) were more satisfying than those without neuroscience information (M = −0.49, SE = 0.16).

There was additionally an interaction effect between explanation type and presence of neuroscience [F(1, 21) = 8.7, p < .01], as in Experiment 1. Post hoc analyses indicate that this interaction happens for the same reason as in Experiment 1: Ratings of bad explanations increased reliably more with the addition of neuroscience than did good explanations. Unlike the novices, the students judged that both good explanations and bad explanations were significantly more satisfying when they contained neuroscience, but the bad explanations were judged to have improved more dramatically, based on a comparison of the differences in ratings between explanations with and without neuroscience [t(21) = 2.98, p < .01]. Specialized training thus did not discourage the students from judging that irrelevant neuroscience information somehow contributed positively to both types of explanation.

Additionally, our analyses found no main effect of time, showing that classroom training did not affect the students’ performance. Ratings before taking the class and after completing the class were not significantly different [F(1, 21) = 0.13, p > .10], and there were no interactions between time and explanation type [F(1, 21) = 0.75, p > .10] or between time and presence of neuroscience [F(1, 21) = 0.0, p > .10], and there was no three-way interaction among these variables [F(1, 21) = 0.31, p > .10]. The only difference between the preclass data and the postclass data was a significant interaction between sex and neuroscience information in the pre-class data [F(1, 20) = 8.5, p < .01], such that the difference between women’s preclass satisfaction ratings for the Without Neuroscience and the With Neuroscience conditions was significantly larger than this difference in the men’s ratings. This effect did not hold in the postclass test, however. These analyses strongly indicate that whatever training subjects received in the neuroscience class did not affect their performance in the task.

These two studies indicate that logically irrelevant neuroscience information has a reliably positive impact on both novices’ and students’ ratings of explanations, particularly bad explanations, that contain this information. One concern with this conclusion is our assumption that the added neuroscience information really was irrelevant to the explanation. Although we had checked our items with cognitive neuroscientists beforehand, it is still possible that subjects interpreted some aspect of the neuroscience information as logically relevant or content-rich, which would justify their giving higher ratings to the items with neuroscience information. The subjects’ differential performance with good and bad explanations speaks against this interpretation, but perhaps something about the neuroscience information genuinely did improve the bad explanations.

Experiment 3 thus tests experts in neuroscience, who would presumably be able to tell if adding neuroscience information should indeed make these explanations more satisfying. Are experts immune to the effects of neuroscience information because their expertise makes them more accurate judges? Or are experts also somewhat seduced by the allure of neuroscience information?

EXPERIMENT 3

Methods

Subjects and Procedure

Forty-eight neuroscience experts participated in the study (29 women, 19 men; mean age = 27.5 years, SD = 5.3 years, range = 21–45 years). There were 28 subjects in the Without Neuroscience condition and 20 subjects in the With Neuroscience condition.

We defined our expert population as individuals who are about to pursue, are currently pursuing, or have completed advanced degrees in cognitive neuroscience, cognitive psychology, or strongly related fields. Our participant group contained 6 participants who had completed college, 29 who were currently in graduate school, and 13 who had completed graduate school.

The materials and procedure in this experiment were identical to Experiment 1, with the addition of four demographic questions in order to confirm the expertise of our subjects. We asked whether they had ever participated in a neuroscience study, designed a neuroscience study, designed a psychological study that did not necessarily include a neuroscience component, and studied neuroscience formally as part of a course or lab group. The average score on these four items was 2.9 (SD = 0.9), indicating a high level of expertise among our participants.

Results and Discussion

Preliminary analyses revealed no differences in performance based on sex or level of education, so all subsequent analyses do not consider these variables. We additionally found acceptably consistent responding to the 18 items (Cronbach’s α = .71).

We analyzed subjects’ ratings of explanatory satisfaction in a 2 (good explanation vs. bad explanation) × 2 (without neuroscience vs. with neuroscience) repeated measures ANOVA (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Expert group. Mean ratings of how satisfying subjects found the explanations. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

We found a main effect of explanation type [F(1, 46) = 54.9, p < .01]. Just like the novices and students, the experts rated good explanations (M = 0.19, SE = 0.11) as significantly more satisfying than bad ones (M = 0.99, SE = 0.14).

Unlike the data from the other two groups, the experts’ data showed no main effect of neuroscience, indicating that subjects rated explanations in the same way regardless of the presence of neuroscience information [F(1, 46) = 1.3, p > .10].

This lack of a main effect must be interpreted in light of a significant interaction between explanation type and presence of neuroscience [F(1, 46) = 8.9, p < .01]. Post hoc analyses reveal that this interaction is due to a differential effect of neuroscience on the good explanations: Good explanations with neuroscience (M = −0.22, SE = 0.21) were rated as significantly less satisfying than good explanations without neuroscience [M = 0.41, SE = 0.13; F(1, 46) = 8.5, p < .01]. There was no change in ratings for the bad explanations (without neuroscience M = −1.07, SE = 0.19; with neuroscience M = −0.87, SE = 0.21). This indicates that experts are so attuned to proper uses of neuroscience that they recognized the insufficiency of the neuroscience information in the With Neuroscience condition. This recognition likely led to the drop in satisfaction ratings for the good explanations, whereas bad explanations could not possibly have been improved by what the experts knew to be an improper application of neuroscience information. Informal post hoc questioning of several participants in this study indicated that they were indeed sensitive to the awkwardness and irrelevance of the neuroscience information in the explanations.

These results from expert subjects confirm that the neuroscience information in the With Neuroscience conditions should not be seen as adding value to the explanations. The results from the two nonexpert groups are thus due to these subjects’ misinterpretations of the neuroscience information, not the information itself.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Summary of Results

The three experiments reported here explored the impact of adding scientific-sounding but empirically and conceptually uninformative neuroscience information to both good and bad psychological explanations. Three groups of subjects (novices, neuroscience class students, and neuroscience experts) read brief descriptions of psychological phenomena followed by a good or bad explanation that did or did not contain logically irrelevant neuroscience information. Although real neuropsychological data certainly can provide insight into behavior and into psychological mechanisms, we specifically wanted to investigate the possible effects of the presence of neuroscience information, regardless of the role that this information plays in an explanation. The neuroscience information in the With Neuroscience condition thus did not affect the logic or content of the psychological explanations, allowing us to see whether the mere mention of a neural process can affect subjects’ judgments of explanations.

We analyzed subjects’ ratings of how satisfying they found the explanations in the four conditions. We found that subjects in all groups could tell the difference between good explanations and bad explanations, regardless of the presence of neuroscience. Reasoning about these types of explanations thus does not seem to be difficult in general because even the participants in our novice group showed a robust ability to differentiate between good and bad explanations.

Our most important finding concerns the effect that explanatorily irrelevant neuroscience information has on subject’s judgments of the explanations. For novices and students, the addition of such neuroscience information encouraged them to judge the explanations more favorably, particularly the bad explanations. That is, extraneous neuroscience information makes explanations look more satisfying than they actually are, or at least more satisfying than they otherwise would be judged to be. The students in the cognitive neuroscience class showed no benefit of training, demonstrating that only a semester’s worth of instruction is not enough to dispel the effect of neuroscience information on judgments of explanations. Many people thus systematically misunderstand the role that neuroscience should and should not play in psychological explanations, revealing that logically irrelevant neuroscience information can be seductive—it can have much more of an impact on participants’ judgments than it ought to.

However, the impact of superfluous neuroscience information is not unlimited. Although novices and students rated bad explanations as more satisfying when they contained neuroscience information, experts did not. In fact, subjects in the expert group tended to rate good explanations with neuroscience information as worse than good explanations without neuroscience, indicating their understanding that the added neuroscience information was inappropriate for the phenomenon being described. There is thus some noticeable benefit of extended and specific training on the judgment of explanations.

Why are Nonexperts Fooled?

Nonexperts judge explanations with neuroscience information as more satisfying than explanations without neuroscience, especially bad explanations. One might be tempted to conclude from these results that neuroscience information in explanations is a powerful clue to the goodness of explanations; nonexperts who see neuroscience information automatically judge explanations containing it more favorably. This conclusion suggests that these two groups of subjects fell prey to a reasoning heuristic (e.g., Shafir, Smith, & Osherson, 1990; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974, 1981). A plausible heuristic might state that explanations involving more technical language are better, perhaps because they look more “scientific.” The presence of such a heuristic would predict that subjects should judge all explanations containing neuroscience information as more satisfying than all explanations without neuroscience, because neuroscience is itself a cue to the goodness of an explanation.

However, this was not the case in our data. Both novices and students showed a differential impact of neuroscience information on their judgments such that the ratings for bad explanations increased much more markedly than ratings for good explanations with the addition of neuroscience information. This interaction effect suggests that an across-the-board reasoning heuristic is probably not responsible for the nonexpert subjects’ judgments.

We see a closer affinity between our work and the so-called seductive details effect (Harp & Mayer, 1998; Garner, Alexander, Gillingham, Kulikowich, & Brown, 1991; Garner, Gillingham, & White, 1989). Seductive details, related but logically irrelevant details presented as part of an argument, tend to make it more difficult for subjects to encode and later recall the main argument of a text. Subjects’ attention is diverted from important generalizations in the text toward these interesting but irrelevant details, such that they perform worse on a memory test and have a harder time extracting the most important points in the text.

Despite the strength of this seductive details effect in this previous work and in our current work, it is not immediately clear why nonexpert participants in our study judged that seductive details, in the form of neuroscience information, made the explanations we presented more satisfying. Future investigations into this effect could answer this question by including qualitative measures to determine precisely how subjects view the differences among the explanations. In the absence of such data, we can question whether something about neuroscience information in particular did the work of fooling our subjects. We suspect not—other kinds of information besides neuroscience could have similar effects. We focused the current experiments on neuroscience because it provides a particularly fertile testing ground, due to its current stature both in psychological research and in the popular press. However, we believe that our results are not necessarily limited to neuroscience or even to psychology. Rather, people may be responding to some more general property of the neuroscience information that encouraged them to find the explanations in the With Neuroscience condition more satisfying.

To speculate about the nature of this property, people seeking explanations may be biased to look for a simple reductionist structure. That is, people often hear explanations of “higher-level” or macroscopic phenomena that appeal to “lower-level” or microscopic phenomena. Because the neuroscience explanations in the current study shared this general format of reducing psychological phenomena to their lower-level neuroscientific counterparts, participants may have jumped to the conclusion that the neuroscience information provided them with a physical explanation for a behavioral phenomenon. The mere mention of a lower level of analysis may have made the bad behavioral explanations seem connected to a larger explanatory system, and hence more insightful. If this is the case, other types of logically irrelevant information that tap into a general reductionist framework could encourage people to judge a wide variety of poor explanations as satisfying.

There are certainly other possible mechanisms by which neuroscience information may affect judgments of explanations. For instance, neuroscience may illustrate a connection between the mind and the brain that people implicitly believe not to exist, or not to exist in such a strong way (see Bloom, 2004a). Additionally, neuroscience is associated with powerful visual imagery, which may merely attract attention to neuroscience studies but which is also known to interfere with subjects’ abilities to explain the workings of physical systems (Hayes, Huleatt, & Keil, in preparation) and to render scientific claims more convincing (McCabe & Castel, in press). Indeed, it is possible that “pictures of blobs on brains seduce one into thinking that we can now directly observe psychological processes” (Henson, 2005, p. 228). However, the mechanism by which irrelevant neuroscience information affects judgment may also be far simpler: Any meaningless terminology, not necessarily scientific jargon, can change behavior. Previous studies have found that providing subjects with “placebic” information (e.g., “May I use the Xerox machine; I have to make copies?”) increases compliance with a request over and above a condition in which the researcher simply makes the request (e.g., “May I use the Xerox machine?”) (Langer, Blank, & Chanowitz, 1978).

These characteristics of neuroscience information may singly or jointly explain why subjects judged explanations containing neuroscience information as generally more satisfying than those that did not. But the most important point about the current study is not that neuroscience information itself causes subjects to lose their grip on their normally well-functioning judgment processes. Rather, neuroscience information happens to represent the intersection of a variety of properties that can conspire together to impair judgment. Future research should aim to tease apart which properties are most important in this impairment, and indeed, we are planning to follow up on the current study by examining comparable effects in other special sciences. We predict that any of these properties alone would be sufficient for our effect, but that they are more powerful in combination, hence especially powerful for the case of neuroscience, which represents the intersection of all four.

Regardless of the breadth of our effect or the mechanism by which it occurs, the mere fact that irrelevant information can interfere with people’s judgments of explanations has implications for how neuroscience information in particular, and scientific information in general, is viewed and used outside of the laboratory. Neuroscience research has the potential to change our views of personal responsibility, legal regulation, education, and even the nature of the self (Farah, 2005; Bloom, 2004b). To take a recent example, some legal scholars have suggested that neuroimaging technology could be used in jury selection, to ensure that jurors are free of bias, or in questioning suspects, to ensure that they are not lying (Rosen, 2007). Given the results reported here, such evidence presented in a courtroom, a classroom, or a political debate, regardless of the scientific status or relevance of this evidence, could strongly sway opinion, beyond what the evidence can support (see Feigenson, 2006). We have shown that people seem all too ready to accept explanations that allude to neuroscience, even if they are not accurate reflections of the scientific data, and even if they would otherwise be seen as far less satisfying. Because it is unlikely that the popularity of neuroscience findings in the public sphere will wane any time soon, we see in the current results more reasons for caution when applying neuroscientific findings to social issues. Even if expert practitioners can easily distinguish good neuroscience explanations from bad, they must not assume that those outside the discipline will be as discriminating.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Bloom, Martha Farah, Michael Weisberg, two anonymous reviewers, and all the members of the Cognition and Development Lab for their conversations about this work. Special thanks is also due to Marvin Chun, Marcia Johnson, Christy Marshuetz, Carol Raye, and all the members of their labs for their assistance with our neuroscience items. We acknowledge support from NIH Grant R-37-HD023922 to F. C. K.

Footnotes

Because we constructed the stimuli in the With neuroscience conditions by modifying the explanations from the Without Neuroscience conditions, both the good and the bad explanations in the With Neuroscience conditions appear less elegant and less parsimonious than their without-neuroscience counterparts, as can be seen in Table 1. But this design provides an especially stringent test of our hypothesis: We expect that explanations with neuroscience will be judged as more satisfying than explanations without, despite cosmetic and logical flaws.

REFERENCES

- Bloom P. Descartes’ baby. New York: Basic Books; 2004a. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom P. The duel between body and soul. The New York Times. 2004b:A25. [Google Scholar]

- Farah MJ. Neuroethics: The practical and the philosophical. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenson N. Brain imaging and courtroom evidence: On the admissibility and persuasiveness of fMRI. International Journal of Law in Context. 2006;2:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Garner R, Alexander PA, Gillingham MG, Kulikowich JM, Brown R. Interest and learning from text. American Educational Research Journal. 1991;28:643–659. [Google Scholar]

- Garner R, Gillingham MG, White CS. Effects of “seductive details” on macroprocessing and microprocessing in adults and children. Cognition and Instruction. 1989;6:41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Harp SF, Mayer RE. How seductive details do their damage: A theory of cognitive interest in science learning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1998;90:414–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes BK, Huleatt LA, Keil F. Mechanisms underlying the illusion of explanatory depth. (in preparation) [Google Scholar]

- Henson R. What can functional neuroimaging tell the experimental psychologist? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2005;58A:193–233. doi: 10.1080/02724980443000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil FC. Explanation and understanding. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;51:227–254. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen D. Function, goals, and intention: Children’s teleological reasoning about objects. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1999;3:461–468. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikas E. University students’ conceptions of different physical phenomena. Journal of Adult Development. 2003;10:139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Langer E, Blank A, Chanowitz B. The mindlessness of ostensibly thoughtful action: The role of “placebic” information in interpersonal interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1978;36:635–642. [Google Scholar]

- Lombrozo T. The structure and function of explanations. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;10:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombrozo T, Carey S. Functional explanation and the function of explanation. Cognition. 2006;99:167–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe DP, Castel AD. Seeing is believing: The effect of brain images as judgments of scientific reasoning. Cognition. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.07.017. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rips LJ. Circular reasoning. Cognitive Science. 2002;26:767–795. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J. The brain on the stand. The New York Times Magazine. 2007 March 11;:49. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenblit L, Keil F. The misunderstood limits of folk science: An illusion of explanatory depth. Cognitive Science. 2002;92:1–42. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog2605_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafir EB, Smith EE, Osherson DN. Typicality and reasoning fallacies. Memory & Cognition. 1990;18:229–239. doi: 10.3758/bf03213877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trout JD. Scientific explanation and the sense of understanding. Philosophy of Science. 2002;69:212–233. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211:453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]