Abstract

A breakthrough for studying the neuronal basis of learning emerged when invertebrates with simple nervous systems, such as the sea slug Hermissenda crassicornis, were shown to exhibit classical conditioning. Hermissenda learns to associate light with turbulence: prior to learning, naive animals move toward light (phototaxis) and contract their foot in response to turbulence; after learning, conditioned animals delay phototaxis in response to light.

The photoreceptors of the eye, which receive monosynaptic inputs from statocyst hair cells, are both sensory neurons and the first site of sensory convergence. The memory of light associated with turbulence is stored as changes in intrinsic and synaptic currents in these photoreceptors. The subcellular mechanisms producing these changes include activation of protein kinase C and MAP kinase, which act as coincidence detectors because they are activated by convergent signaling pathways.

Pathways of interneurons and motorneurons, where additional changes in excitability and synaptic connections are found, contribute to delayed phototaxis. Bursting activity recorded at several points suggest the existence of small networks that produce complex spatio-temporal firing patterns. Thus, the change in behavior may be produced by a non-linear transformation of spatio-temporal firing patterns caused by plasticity of synaptic and intrinsic channels.

The change in currents and the activation of PKC and MAPK produced by associative learning are similar to that observed in hippocampal and cerebellar neurons after rabbit classical conditioning, suggesting that these represent general mechanisms of memory storage. Thus, the knowledge gained from further study of Hermissenda will continue to illuminate mechanisms of mammalian learning.

ASSOCIATIVE LEARNING BEHAVIOR

Learning and Memory

Learning is “a relatively long lasting and adaptive change in behavior resulting from experience” (Hall, 1976). The breadth of species which exhibit learning is astounding, ranging from worms (Rankin, 2004) to humans. Nonetheless the capacity for learning varies greatly among species, being exceedingly large in primates as compared to most other mammals (Lefebvre, Reader, and Sol, 2004). The long developmental period of primates is coupled to learning how to survive in the environment; the expense of a long developmental period is repaid in the form of extreme flexibility and adaptability.

Memory is intricately tied to learning, because memory is the storage of what we have learned. Thus, learning is analogous to the procedure producing the change in behavior, but memory is the physical change to the organism which allows the behavior to endure. A fascinating aspect of learning and memory is that there is a dichotomy in the types of learning, which is reflected in our language. Explicit memory is the memory for facts and events; implicit memory is the memory for skills (Squire and Zola, 1996). When we learn facts and events, we have it in memory, or have memorized the information. When we learn a skill, that too is stored in memory, but as a capability, or enhancement of skill performance.

Another intriguing aspect of learning and memory is that most of the time, we are learning associations. From the earliest age, an infant learns to associate the smell of its mother with being fed, thus the infant calms when the mother picks it up, even prior to being fed. Both our language “that reminds me of ….”, and “looks like rain”, as well as observations that students learn information better when it is related to what they already know, is additional evidence of the associative nature of learning and memory.

Classical Conditioning

A breakthrough in the study of learning came with the development of an animal model of an associative form of learning called classical conditioning, developed by the Russian physiologist Pavlov (Windholz, 1989). Originally, Pavlov was studying glandular secretions involved in digestion, and was inducing dogs to salivate by giving them food. The delivery of food was preceded by a sound such as a bell. The dogs learned that the bell predicted the food, and began salivating in response to the bell. This early salivation response actually interfered with the original experiments, but Pavlov was clever enough to realize that this was an adaptive or learned behavior useful for studying the brain.

Continuous study during the last century has helped to define and delineate classical conditioning (Hall, 1976). In Pavlov’s paradigm the bell, which initially does not evoke a response, is the conditioned stimulus (CS); the meat, which elicits a response prior to training, is the unconditioned stimulus (US; see Table 1 for a list of abbreviations). After repeated presentations of the CS (sound) followed by the US (food), the sound alone evokes a response, called the conditioned response (CR). One of the hallmarks of classical conditioning is that the timing between the CS and US presentation is critical. If the CS is presented after the US, the animal will never learn that the CS predicts the US. Thus, the CS must be presented before the US, and the time between CS and US presentation should not be too long (though the limiting length depends on the species and other characteristics of CS and US).

Table 1.

Abbreviations

| CR | Conditioned Response |

| CS | Conditioned Stimulus |

| UR | Unconditioned Response |

| US | Unconditioned Stimulus |

| AA | Arachidonic Acid |

| DAG | Diacylglycerol |

| IP3 | Inositol triphosphate |

| ERK | Extra-cellular signal related protein kinase |

| MAPK | Mitogen activated protein kinase |

| MEK1 | ERK-activated kinase |

| PKA | Protein Kinase A |

| PKC | Protein Kinase C |

| PLA2 | Phospholipase A2 |

| RyR | Ryanodine Receptor |

| CPG | Central Pattern Generator |

| IPSP | Inhibitory post synaptic potential |

| EPSP | Excitatory post synaptic potential |

In-depth study by psychologists of factors constraining classical conditioning were designed to determine the physical changes corresponding to memory storage. In other words, classical conditioning was considered a learning paradigm to determine how the brain controls learning behavior. Behavioral techniques coupled with neurophysiology techniques such as extracellular recording of neuronal activity or focal brain lesions revealed that multiple neuronal circuits participate in this simple form of learning. One set of sensory neuronal circuits transforms external conditioned and unconditioned stimuli into neuronal activity patterns. Another set of motor neuronal circuits transforms neuronal activity patterns into behavior. A third, distinct set of neuronal circuits stores the memory: the activity patterns of these neurons is transformed when CS and US stimuli are presented with the correct temporal sequence (Berger, Rinaldi, Weisz, and Thompson, 1983). The most important question remains: how do neurons store memories. In other words, what are the mechanisms whereby activity patterns of the “memory storage” neurons are transformed?

Invertebrate Classical Conditioning

A breakthrough for studying the neuronal basis of learning emerged when invertebrates such as Hermissenda crassicornis were shown to exhibit such behavior (Crow and Alkon, 1978). Hermissenda is a small, nudibranch mollusk, also known as a seaslug, that lives in the coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean, e.g. off the coast of Monterey, California. Hermissenda learns to associate light, the CS, with turbulence, the US. Prior to learning, naive animals move forward in response to light and contract their foot in response to turbulence; after learning, conditioned animals contract their foot in response to light, and delay forward movement toward the light. It is important to point out that these are stimuli that appear in Hermissenda’s natural environment; thus, light is a surrogate for sunlight, and turbulence is the surrogate for wave action. This behavior is adaptive in that during storms, when the water is extremely turbulent, Hermissenda learns to avoid moving toward the surface of the water, and instead contracts its foot in order to cling to a rock or other structure.

Many of the behavioral characteristics of Hermissenda classical conditioning are similar to those found in mammalian classical conditioning (Crow and Alkon, 1978;Schreurs and Alkon, 2001). Hermissenda do not learn if presented with light alone, or turbulence alone. Learning requires that the light occurs prior to turbulence, and that turbulence follows within a few seconds. Other behavioral properties include contingency sensitivity: both Hermissenda and other animals learn more slowly if unpaired stimuli are interspersed with paired stimuli; and savings: Hermissenda that have previously learned and forgotten an association learn more quickly the second time. Other behavioral characteristics of classical conditioning, both those shared with mammals, and higher order mammalian characteristics lacking in Hermissenda, are reviewed elsewhere (Matzel, Talk, Muzzio, and Rogers, 1998;Crow, 2004).

NEURONAL CORRELATES OF CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

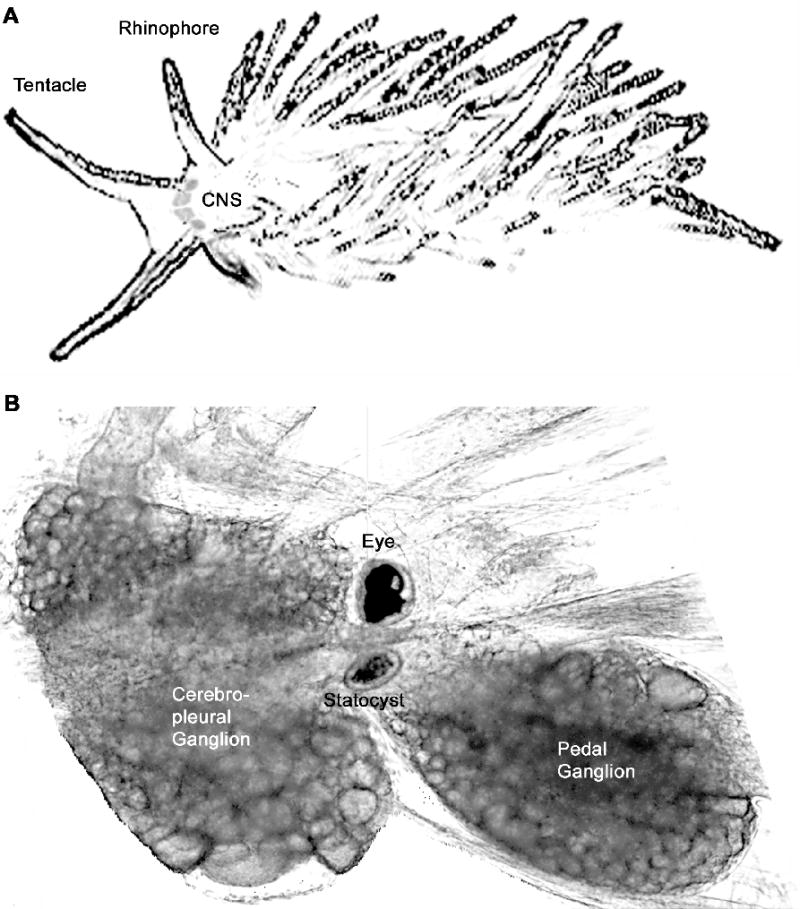

For neuroscientists, classical conditioning is a paradigm used to probe deeper questions of how the brain stores memories. Thus, the unquestionable value in studying classical conditioning in Hermissenda is attributed to its simple nervous system, and the ability to measure neuronal changes corresponding to the memory trace. The central nervous system consists of paired cerebropleural ganglia, pedal ganglia, eyes, and statocysts, the vestibular organs composed of thirteen hair cells that sense acceleration (Fig 1). Compared to the billions of neurons in the mammalian brain, the thousands of neurons in the Hermissenda brain and the stereotypical configuration of many of these neurons allows for precise investigation of neuronal properties and neuronal networks participating in memory storage and expression. Furthermore, it is possible to remove the entire central nervous system and apply the same paired stimuli of classical conditioning to this in vitro nervous system. Thus, the in vitro preparation allows scientists to probe the inner workings of neurons while memories are being stored.

Fig 1.

Hermissenda central nervous system. A. Sketch of seaslug showing approximate size and central nervous system (CNS) location behind the tentacles and between the rhinophores. B. Half of the central nervous system of Hermissenda. The photoreceptors are visible on the periphery of the eye; in the center they are obscured by pigment cells. The statocyst consists of a sphere of 13 hair cells and centrally located statoconia. The optic gagnlia is a small collection of cells between the statocyst and the eye. Not picture is the buccal ganglia, which are connected to the pedal ganglia. Somatosensory and chemosensory inputs from tentacles and rhinophores are connected via nerves to the cerebropleural ganglia.

Photoreceptors comprise the sensory neurons for the CS

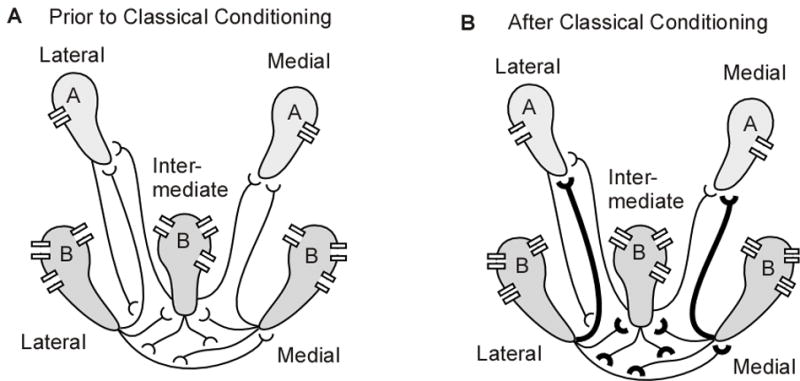

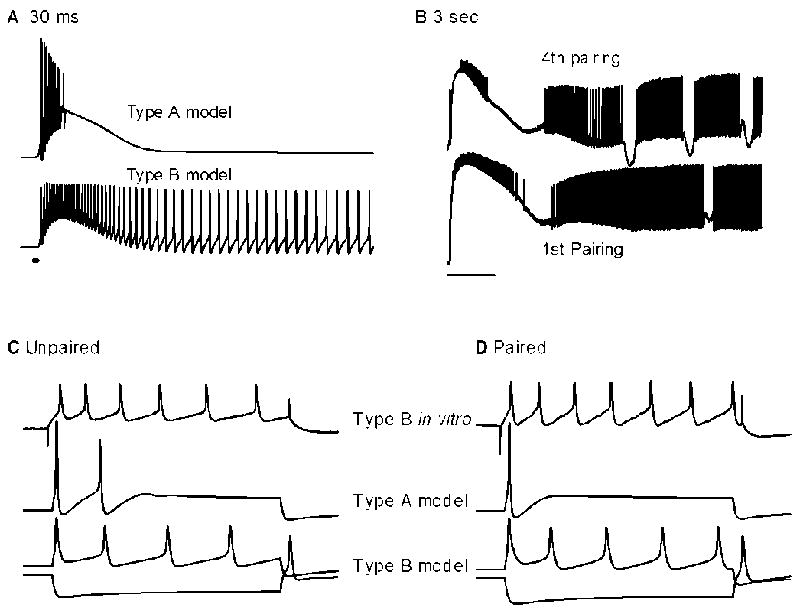

Each of the Hermissenda eyes has three type B and two type A photoreceptors (Stensaas, Stensaas, and Trujillo-Cenoz, 1969)(Fig 2A). The photoreceptors are sensory cells for the CS stimulus and transduce light energy into depolarization. The type A and type B photoreceptors exhibit characteristic differences, reminiscent of the difference between mammalian rods and cones: Type B photoreceptors are sensitive to dimmer lights than are type A photoreceptors (Alkon and Fuortes, 1972;Mo and Blackwell, 2003). The temporal response to light stimuli also differs (Fig 3A). Type A photoreceptors respond to an increase in illumination with a rapid increase in firing frequency, followed by rapid light adaptation (Crow, 1985;Farley, Richards, and Grover, 1990;Yamoah, Matzel, and Crow, 1998;Mo and Blackwell, 2003). When the light stimulus is removed, type A photoreceptors quickly cease firing, a process known as dark adaptation. In contrast, type B photoreceptors fire less strongly in response to an increase in illumination, and they also light adapt less strongly then type A photoreceptors (Crow, 1985;Farley, Richards, and Grover, 1990;Mo and Blackwell, 2003). Thus, after the initial light response, both type A and type B photoreceptors respond at near equal firing frequencies. When returned to darkness, type B photoreceptors continue to fire for prolonged periods, due to their slow dark adaptation. These different response properties suggest different functional roles: type A photoreceptors signal changes in illumination, and type B photoreceptors signal background illumination.

Fig 2.

Network of Hermissenda photoreceptors. (A) Each eye has two type A and three type B photoreceptors. The type B photoreceptors mutually inhibit each other. The type B photoreceptors also inhibit the type A photoreceptors. Several ionic channels are shown schematically. (B) Classical conditioning causes an decrease in conductance of several ionic channel in the type B photoreceptors (narrower channels), and an increase in conductance of the delayed rectifier potassium channel in the type A photoreceptors (wider channels). In addition, the inhibition from type B to type A photoreceptors is increased; the effect of mutual inhibition among type B photoreceptors is increased due to the increase in input resistance.

Fig 3.

Electrical activity of type A and B photoreceptors. (A) Simulated response to 30 ms duration light. Type A photoreceptors gives a brief burst of spikes, and then quickly dark adapts. Type B photoreceptors respond with initially lower firing frequency than type A photoreceptors, but continue to fire for a long time in the dark. (B) Response of type B photoreceptors to in vitro classical conditioning. During the first pairing of 3 s light and 2 s turbulence, the response looks similar to light alone, with a sustained firing for many seconds after light offset. After the fourth pairing, burst firing appears. (C,D) Response to current injection before and after classical conditioning. Type B photoreceptors develop an increase in spike activity, and an increase in input resistance. This change in activity requires a decrease in the transient potassium current, calcium dependent potassium current, calcium current, and leak potassium current. Type A photoreceptors decrease their spike activity. This change is mediated by an increase in the delayed rectifier potassium current.

Photoreceptors play additional role as memory storage neurons

Decades of work by Alkon and colleagues (Crow and Alkon, 1978) have revealed that the photoreceptors are the first site of convergence of the CS and US stimuli, and a key locus of memory storage. The sensory cells for the US are the statocyst hair cells, which transduce turbulence or gravitational energy into depolarization (Detwiler and Fuortes, 1975). Statocyst hair cells release the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (Alkon, Anderson, Kuzirian, Rogers, Fass, Collin, Nelson, Kapetanovic, and Matzel, 1993) onto the terminal branches of the photoreceptors. Thus, during classical conditioning, paired CS and US stimuli produce depolarization and GABA receptor activation of the photoreceptors. When light and turbulence are presented in the correct temporal sequence, intracellular processes are activated and produce intrinsic changes to the photoreceptors. Thus, the memory of the association is stored as a change in response properties of these photoreceptors. Interestingly, type A and B photoreceptors are modulated differently by classical conditioning paradigms.

Intracellular recordings from animals that have been classically conditioned, or from applying a classical conditioning procedure to the in vitro nervous system, have revealed several changes in photoreceptor properties that are correlated with learning behavior, or the presentation of paired stimuli, respectively. Type B photoreceptors show an increase in excitability due to the conditioning procedure, as compared with type B photoreceptors which received the unpaired training procedure (Fig 3C,D). The increase in excitability is exhibited as an increase in input resistance, an increase in the firing frequency due to light stimulation or current injection (Crow and Alkon, 1980;Matzel and Rogers, 1993;Blackwell and Alkon, 1999), and an enhanced long lasting depolarization following light stimulation (Alkon and Grossman, 1978). The increased excitability is accompanied by a reduction of the transient potassium current, the calcium-dependent potassium current, and the persistent calcium current (Alkon, Sakakibara, Forman, Harrigan, Lederhendler, and Farley, 1985)(Collin, Ikeno, Harrigan, Lederhendler, and Alkon, 1988). In contrast, type A photoreceptors exhibit a decrease in excitability (Farley, Richards, and Grover, 1990;Frysztak and Crow, 1993). This includes a decrease in the generator potential, and a decrease in input resistance, which is accompanied by an increase in the delayed rectifier potassium current. The effect of classical conditioning on firing frequency of type A photoreceptors is less clear, with reports of increase (Frysztak and Crow, 1993) and decrease (Farley, Richards, and Grover, 1990;Farley and Han, 1997).

The most exciting aspect of these discoveries is that they may represent general mechanisms of memory storage (Matzel, Talk, Muzzio, and Rogers, 1998;Schreurs and Alkon, 2001;Daoudal and Debanne, 2003). Long term changes in excitability have been demonstrated in rabbits consequent to classical conditioning (Moyer, Jr., Thompson, and Disterhoft, 1996;Schreurs, Gusev, Tomsic, Alkon, and Shi, 1998). An accompanying reduction in afterhyperpolarization suggests that the increase in excitability is mediated by a reduction in potassium currents (Coulter, Lo Turco, Kubota, Disterhoft, Moore, and Alkon, 1989;Schreurs, Gusev, Tomsic, Alkon, and Shi, 1998). Additional evidence for the role of potassium currents comes from genetic studies of Drosophila. Alteration of shaker transient potassium channels or eag potassium channels produces deficits in conditioning (Cowan and Siegel, 1986). Thus, though memory storage in sensory neurons may be unusual, the changes in potassium currents and excitability in neurons receiving convergent inputs is likely to be a general mechanism of memory storage.

Photoreceptor synaptic interactions contribute to memory trace

Another mechanism underlying classical conditioning in Hermissenda is changes in synaptic interactions among photoreceptors. As illustrated in Fig 2A, the type B photoreceptors are mutually inhibitory, and the type A photoreceptors are inhibited by the type B photoreceptors (Alkon and Fuortes, 1972;Goh and Alkon, 1984) (Fig 2A). Classical conditioning enhances the inhibition of medial type A photoreceptors by medial type B photoreceptors (the IPSP is enhanced), but there is no change in inhibition of lateral type A by lateral type B photoreceptors (Frysztak and Crow, 1997). In contrast, in vitro conditioning produces an enhancement of IPSPs from type B to type A photoreceptors, both medial and lateral (Schuman and Clark, 1994) (Fig 2B). There have been no reports of changes in synaptic strength of inhibitory connections between pairs of type B photoreceptors, but the increased input resistance and firing frequency would produce enhanced inhibition regardless of whether the synapse itself were modulated. Furthermore, action potential width in type B photoreceptors is increased (Gandhi and Matzel, 2000), which may be accompanied by an increase in calcium influx and consequent increase in release probability. In summary, classical conditioning potentiates synaptic interactions not only by synaptic mechanisms, but also secondary to the modulation of voltage dependent channels and membrane properties.

Long term synaptic potentiation, specifically that produced by synaptic mechanisms, has long been studied as a mechanism of memory storage in mammals (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993;Malinow and Malenka, 2002). Despite decades of study, the connection between memory and hippocampal LTP is tenuous (Teyler and DiScenna, 1984;Shors and Matzel, 1997). Perhaps the strongest evidence for synaptic plasticity as a mechanism of memory storage is observed in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala. In vivo recordings in rats reveal synaptic potentiation after fear conditioning but not in unpaired controls (Blair, Schafe, Bauer, Rodrigues, and LeDoux, 2001). In mammals, addressing how synaptic plasticity produces a change in behavior is inaccessible due to the large number of neurons and synapses involved in producing behavior. In contrast, further studies of Hermissenda may reveal scalable mechanisms whereby changes in synaptic plasticity produce changes in activity patterns that control behavior.

Modulation of ionic and synaptic channels produce change in spatio-temporal firing patterns

How is modulation of ionic and synaptic channels translated into a change in behavior? A novel approach to this question involves considering the five photoreceptors as a small neuronal network (Fost and Clark, 1996b). The light response of this network constitutes a spatio-temporal firing pattern that is shaped by inhibitory interactions among photoreceptors. Modulation of both synaptic and ionic currents transforms the spatio-temporal pattern in a non-linear manner due to the inhibitory synaptic interactions. In this manner, the increase in variance of the interspike interval due to classical conditioning (Crow, 1985) may be due to the non-linear transformation from tonically firing to periodic burst firing (Fig 8 of (Mo and Blackwell, 2003); Fig 2B).

Periodic burst firing patterns are seen in many systems, such as networks with mutually inhibitory interactions and sustained excitatory inputs (Popescu and Frost, 2002), and networks of coupled excitation and inhibition (Warren, Agmon, and Jones, 1994). Both of these network configurations are present in the visual system of Hermissenda. Mutual inhibition with excitation is present in the three mutually inhibitory type B photoreceptors; tonic excitatory input is provided by the light-induced long lasting depolarization (Alkon and Grossman, 1978). Coupled excitation and inhibition is seen in connections between type B cells and optic ganglion cells: the photoreceptors inhibit optic ganglion cells; and optic ganglion cells excite type B photoreceptors (Alkon, 1980a). Both strength and persistence of neuronal synaptic interactions influence the occurrence of and characteristics of periodic activity (White, Banks, Pearce, and Kopell, 2000). Thus, periodic bursting may develop after classical conditioning due to the increased strength of inhibitory interactions among type B photoreceptors.

Computational models investigate relationship between ionic channels and neuronal activity

The Hermissenda community has a strong tradition of computational modeling to integrate and synthesize results from myriad experiments into a coherent view of neuronal memory storage. The ultimate goal with such models is to demonstrate how paired stimuli produce changes in neuronal properties, neuronal activity, and motor output. An additional advantage of computational models is to explicate and evaluate the assumptions that always accompany conceptual models. Presently, computational models of Hermissenda photoreceptors have been used primarily to investigate two issues. The first is the second messenger mechanisms underlying temporal sensitivity (discussed in the next section), and the second is the mechanisms (ionic currents) underlying the various changes in excitability and synaptic efficacy.

Several models were created to test hypotheses regarding the role of ionic currents in producing the enhanced generator potential, increased spike frequency, synaptic potentiation, and increase in input resistance. These models include voltage dependent, calcium dependent and light induced currents. The first model (Sakakibara, Ikeno, Usui, Collin, and Alkon, 1993) supported the hypothesis that a reduction in the transient and calcium dependent potassium current produces an increased generator potential and enhanced long lasting depolarization. Later models confirmed these results, and in addition showed that the reduction in the calcium dependent potassium current produced a greater influence on the plateau potential and light induced firing frequency than did the transient potassium current (Fost and Clark, 1996a). A reduction in the persistent calcium current and an enhancement in the hyperpolarization activated current, two other ionic current changes correlated with classical conditioning, tended to oppose each other in terms of effect on plateau potential and firing frequency (Cai, Baxter, and Crow, 2003).

The enhancement of synaptic connections is more difficult to explain, and may be produced by mechanisms distinct from the changes in voltage dependent currents. The models above demonstrate that the reduction in the transient potassium current produces spike broadening (Fost and Clark, 1996a;Flynn, Cai, Baxter, and Crow, 2003). Since neurotransmitter release depends on calcium influx, which depends on spike width, this result suggests that a reduction in the transient potassium current produces synaptic facilitation. Nonetheless, when the reduction in transient potassium current is coupled with a reduction in calcium current, not only is the enhanced calcium influx eliminated, but calcium influx is depressed below the control (pre-conditioned) value. Furthermore, an enhancement in the hyperpolarization current does not compensate for the reduced calcium influx, most likely due to inactivation of this current at depolarized potentials. Thus, these four current changes result in a reduction in calcium influx, suggesting that the synaptic facilitation is produced by a mechanism independent of spike broadening, such as modulation of post-synaptic channels or pre-synaptic release probability.

Computational models suggest a role for the light induced potassium current

In all of these models, the enhanced long-lasting depolarization not only requires a reduction in the transient and calcium dependent potassium currents, but also involves the light-induced potassium current. Specifically, the “baseline” long-lasting depolarization, observed in untrained Hermissenda after light offset (Alkon and Grossman, 1978), is produced by the light induced potassium current (Detwiler, 1976;Alkon, Farley, Sakakibara, and Hay, 1984;Blackwell, 2002b;Blackwell, 2004), which has properties similar to leak potassium currents (Buckler, 1999;Donnelly, 1999). This baseline depolarization activates both the transient and calcium dependent potassium currents, which are inactivated at resting potential due to their voltage dependence. A reduction in the transient and calcium dependent potassium currents does not produce an enhanced depolarization in a model lacking the light induced potassium current (Blackwell, 2004).

The light-induced potassium current also may be required to explain the increase in input resistance measured with hyperpolarizing current injection. A decrease in the transient and calcium dependent potassium currents is not sufficient because these currents are not active at resting potential. Similarly, an enhancement in the hyperpolarization activated current, which is active at resting potential, actually decreases the input resistance at hyperpolarized potentials. One possibility, which needs to be evaluated experimentally, is that the light induced potassium current is modified by classical conditioning. Since this current is normally open and conducting at rest, a reduction in this current (either a decrease in total conductance, or a decrease in open probability or duration), would decrease total membrane conductance, and increase input resistance at all membrane potentials (Fig 2C,D).

SUBCELLULAR MECHANISMS FOR TEMPORAL SENSITIVITY

This research in Hermissenda, together with overwhelming evidence from other model systems (Matzel, Talk, Muzzio, and Rogers, 1998;Kandel and Pittenger, 1999), demonstrates that long term memory storage consists of changes in ionic and synaptic currents in individual neurons. This naturally leads to a more intriguing question: What are the subcellular events which lead to modulation of ionic currents when paired stimuli are presented in correct temporal sequence? In other words, what are the subcellular mechanisms that are sensitive to temporal pattern in the photoreceptors of Hermissenda? The requirement for paired stimuli in the behavioral paradigm naturally translates into a requirement for either two different intracellular messengers, or two different sources of a single intracellular messenger molecule.

Elevation in calcium required for memory storage

In Hermissenda photoreceptors, one of the first intracellular messengers identified as meeting this requirement was calcium. Both light stimulation and depolarization produced elevations in calcium via voltage dependent calcium channels (Connor and Alkon, 1984) and release from intracellular stores (Berridge and Galione, 1988;Muzzio, Talk, and Matzel, 1998). The rebound depolarization observed after relief of hair cell inhibition, along with the progressively enhanced depolarization and calcium elevation noted during in vitro training, led to the hypothesis that temporal sensitivity was attributed to the requirement for two sources of calcium: one in response to light, and the second due to depolarization (Alkon, 1980b). This hypothesis was supported by the observation that a calcium elevation was required for the enhanced excitability of type B photoreceptors. Blocking the elevation in calcium (Matzel and Rogers, 1993), or even just one of the calcium sources (Talk and Matzel, 1996;Blackwell and Alkon, 1999), prevented these correlates of memory storage.

Activation of PKC is involved in memory storage

Protein kinase C (PKC) was the second intracellular molecule identified as playing a critical role in classical conditioning. Classical conditioning produces a translocation of PKC from the cytosol to the membrane (Muzzio, Talk, and Matzel, 1997) and PKC phosphorylates the transient and calcium dependent potassium channels, decreasing their maximum conductance and producing an increased input resistance and evoked spike frequency (Neary, Crow, and Alkon, 1981;Farley and Auerbach, 1986). More importantly, PKC requires two or more intracellular messengers for activation: transient activation requires an elevation in calcium and diacylglycerol (Asaoka, Kikkawa, Sekiguchi, Shearman, Kosaka, Nakano, Satoh, and Nishizuka, 1988;Oancea and Meyer, 1998), both of which are produced by light stimulation (Talk and Matzel, 1996;Talk, Muzzio, and Matzel, 1997;Sakakibara, Inoue, and Yoshioka, 1998). Persistent activation of PKC requires not only calcium and diacylglycerol, but also arachidonic acid (Shinomura, Asaoka, Oka, Yoshida, and Nishizuka, 1991;Lester, Collin, Etcheberrigaray, and Alkon, 1991), which is produced by phospholipase A2. Prevention of in vitro classical conditioning with an inhibitor of phospholipase A2 (Talk, Muzzio, and Matzel, 1997) supports the role of arachidonic acid in classical conditioning.

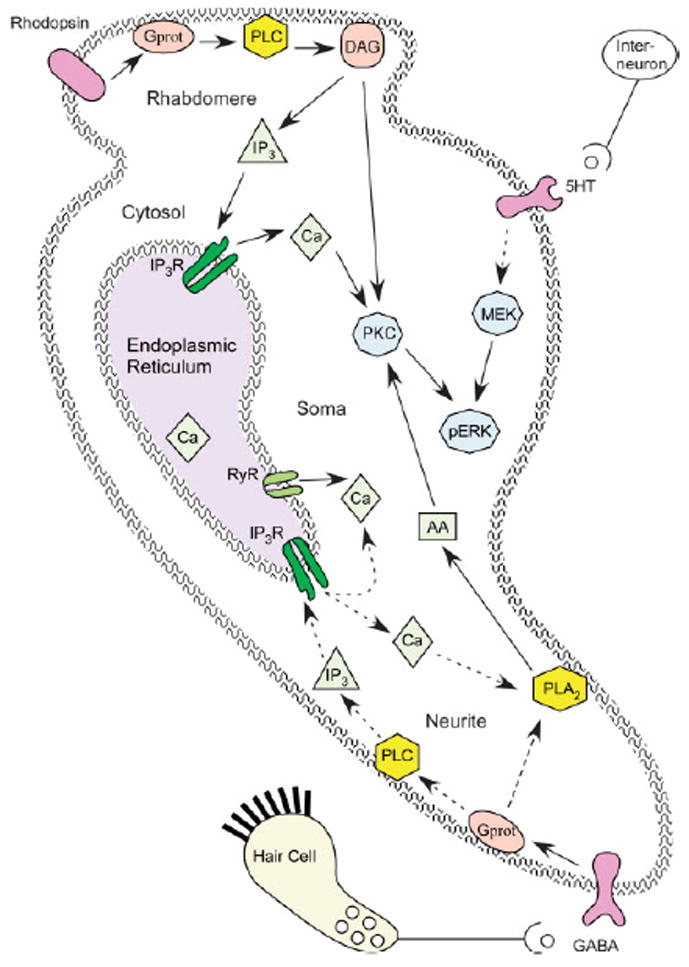

Since light alone produces transient activation of PKC (but does not produce classical conditioning), then turbulence induced hair cell activity must somehow contribute to activation of PLA2 and persistent activation of PKC (Fig 4). Either GABAB receptors are directly coupled to PLA2, or GABAB stimulation produces an elevation in calcium, which combines with the light induced calcium, to produce a larger or more prolonged calcium elevation that activates PLA2 (Hirabayashi, Kume, Hirose, Yokomizo, Iino, Itoh, and Shimizu, 1999). The possibility that GABAB stimulation contributes to the calcium elevation in the soma (independent of the effect on membrane potential) was suggested by the observation of a calcium wave propagating from the terminal branches to the soma (Ito, Oka, Collin, Schreurs, Sakakibara, and Alkon, 1994). Moreover, dantrolene, which prevents the propagation of calcium waves, prevents in vitro classical conditioning of Hermissenda (Blackwell and Alkon, 1999).

Fig 4.

Subcellular mechanisms underlying classical conditioning. Molecules are color coded as follows: Receptors are purple, membrane permeability messengers are pink; membrane bound enzymes are yellow; diffusible messengers are light green; calcium release channels are dark green; enzymes ultimately responsible for long term memory storage are light blue. Solid lines indicate known pathways; dashed lines indicate hypothesized or multi-step pathways. Light activates rhodopsin and a second messenger cascade that produces an increase in DAG and calcium. GABAB receptor stimulation produces an increase in arachidonic acid, either by direct activation of PLA2, or by calcium activation of PLA2 (with PLC and IP3 as intermediates). Serotonin leads to an increase in MEK and ERK phosphorylation, though the G proteins and other messengers have not been identified. Possible mechanisms of temporal sensitivity include (1) persistent PKC activation requires light induced DAG and turbulence (GABA) induced AA, or (2) ERK activation requires light induced transient PKC activation and turbulence (serotonin) induced MEK activation.

PLA2 mediates contribution of GABA stimulation to PKC activation

These contributions to the calcium elevation were tested, both experimentally and using model simulations. Model simulations demonstrated that the rebound depolarization produced an enhanced calcium elevation and a cumulative depolarization only when light and hair cell stimulation occur in the correct temporal relationship (Werness, Fay, Blackwell, Vogl, and Alkon, 1993). However, subsequent experiments showed that a cumulative depolarization was not necessary to produce the enhanced calcium (Matzel and Rogers, 1993). The alternative, that GABA stimulation contributes to the calcium elevation in the soma independent of the effect on membrane potential, was evaluated subsequently. Model simulations demonstrated that, if metabotropic GABAB receptors are coupled to phospholipase C, then the GABA stimulation alone initiates a calcium elevation that propagates as a wave (via release through ryanodine receptors) toward the soma (Blackwell, 2002a). However, inactivation of the ryanodine receptor, by the light induced calcium wave propagating from the rhabdomere toward the terminal branches, produces a refractory period and prevents the GABA induced calcium wave from propagating past the light induced calcium wave when the stimuli are paired (Blackwell, 2004). Thus, the CS and US waves destructively interfered with each other, preventing the US induced calcium from adding to the CS induced calcium. This result suggests that a different mechanism activated by hair cell activity combines with the light-induced calcium elevation to initiate memory storage.

A more likely possibility is that GABAB receptors are directly coupled to PLA2 and that GABA released onto the terminal branches leads to production of arachidonic acid. Application of GABA produces an increase in arachidonic acid, comparable to that produced by direct stimulation of PLA2 (Muzzio, Gandhi, Manyam, Pesnell, and Matzel, 2001). Application of an arachidonic acid analogue plus light produces an increase in excitability similar to that seen with classical conditioning, and it is blocked by the PKC inhibitory chelerythrine. Presently, this hypothesis has the most support, but confirmation requires delineation of the G proteins that couple GABAB receptors to PLA2.

Serotonin activated pathways contribute to memory storage

Yet another possibility is that hair cells activate interneurons that release serotonin onto the photoreceptor soma (Land and Crow, 1985). Serotonin is synthesized and released in the Hermissenda nervous system (Auerbach, Grover, and Farley, 1989), and type B photoreceptors depolarize when serotonin is applied to the soma (Rogers and Matzel, 1995). Light paired with serotonin has been shown to be an effective in vivo training paradigm, producing a reduction in phototaxis similar to that observed with standard classical conditioning paradigms (Crow and Forrester, 1986). Light paired with serotonin leads to an enhanced light response (Crow and Bridge, 1985), and a PKC dependent increase in both input resistance and excitability of the type B photoreceptor (Crow, Forrester, Williams, Waxham, and Neary, 1991). The modulation of ionic channels accompanying these changes also are similar to that observed with paired light and hair cell stimulation (Farley and Wu, 1989)(Acosta-Urquidi and Crow, 1993)(Crow and Bridge, 1985). Despite all of this evidence, noone has demonstrated serotonergic projections onto the photoreceptors. Thus, support for serotonin as a critical neurotransmitter requires identifying the neurons that release serotonin due to hair cell stimulation.

Whereas GABAB stimulation produces arachidonic acid that is required for persistent activation of PKC, the precise role of serotonin in the activation of second-messenger systems is poorly understood. Conditioning using light paired with rotation or serotonin induces the activation of ERK1 and ERK2, members of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) family (Crow, Xue-Bian, Siddiqi, Kang, and Neary, 1998), by ERK activating kinase (MEK1; Fig 4). via both PKC-dependent and PKC-independent pathways (Crow, Xue-Bian, Siddiqi, and Neary, 2001). In mammals (Sweatt, 2001), MAPK kinase is activated by a MAPK kinase kinase such as Raf-1 or B-Raf, which are activated (directly or via intermediaries) by PKC, protein kinase A (PKA), or growth factor tyrosine kinase receptors. In Aplysia, serotonin receptors are coupled to PKA activation and subsequent ERK activation (Barbas, DesGroseillers, Castellucci, Carew, and Marinesco, 2003). Whether PKA or tyrosine kinase is involved in ERK activation in Hermissenda photoreceptors, and the role of ERK in temporal sensitivity awaits further study.

CIRCUITRY

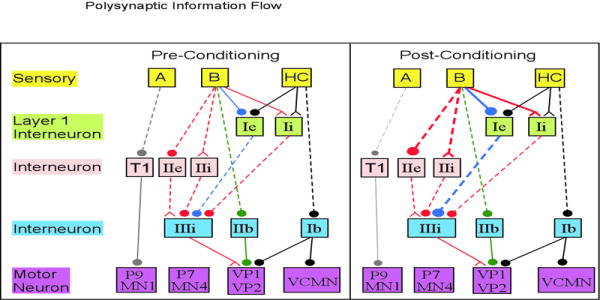

Classical conditioning leads to a change in the spatio-temporal firing pattern of the set of five photoreceptors, which is further transformed into a qualitative change in motorneuron activation by interactions within interneuron layers. Which neurons are involved, and how do they interact to transform the spatio-temporal firing pattern into a change in behavior? Many of the relevant interneurons in the cerebropleural ganglia and motorneurons in the pedal ganglia have been characterized.

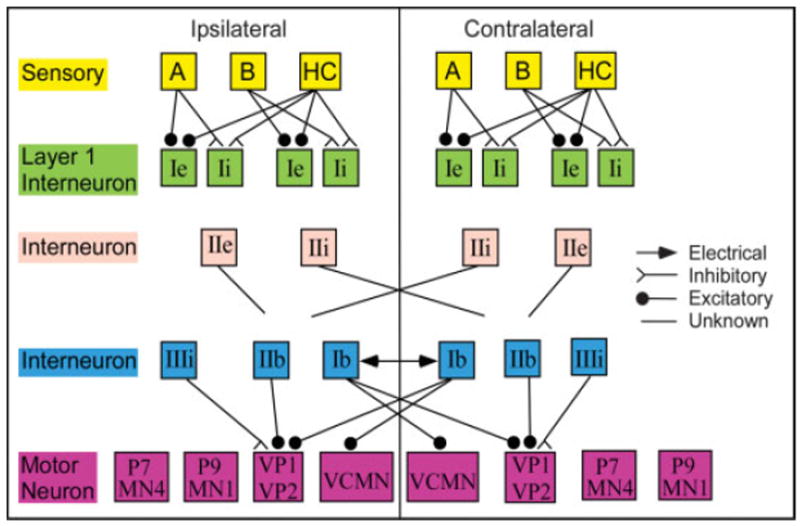

Light sensitive interneurons receive mono- and poly-synaptic input from photoreceptors

One layer of interneurons in the cerebropleural ganlia, which are spontaneously active, are called central visual neurons or type I interneurons (Crow and Tian, 2002b). These interneurons receive either EPSPs (type α or Ie) or IPSPs (type β or Ii) through a direct synaptic connection from ipsilateral type B photoreceptors. These interneurons also receive hair cell inputs of the same sign as type B photoreceptor inputs, i.e., interneurons that received EPSPs from type B photoreceptors also received EPSPs from hair cells (Fig 5). Note that the connections from photoreceptors to type I interneurons is not indiscriminate and convergent, but highly targeted and divergent. Each photoreceptor makes connections to several type I interneurons, but each type I interneuron receives inputs from only a single photoreceptor. Thus, lateral and medial photoreceptors do not project to the same interneurons, nor do type A and type B photoreceptors project to the same interneurons.

Fig 5.

Interneurons and motorneurons involved in phototaxis and foot contractions. Only established monosynaptic connections are illustrated. The post-synaptic targets of the IIe and IIe interneurons have not been identified, thus the connections only indicate whether the projections are ipsilateral or contralateral. Only a single type A photoreceptor, type B photoreceptor, hair cell, Ii interneuron and Ie interneuron is illustrated. In reality, the multiple photoreceptors project to unique layer I interneurons.

A second layer of interneurons are light sensitive but do not receive monosynaptic projections from photoreceptors. These spontaneously active neurons are called type II interneurons. The type IIe interneurons receive polysynaptic excitatory input from photoreceptors and project primarily to the ipsi-lateral pedal ganglion. The type IIi interneurons receive polysynaptic inhibitory input from photoreceptors and project to unidentified neurons in the contralateral cerebropleural ganglion (Crow and Tian, 2002b).

The role of dorsal motorneurons in delayed phototaxis

The first set of light responsive motorneurons studied are located on the dorsal surface of the pedal ganglia. These motorneurons are spontaneously active in the dark. Some of the motorneurons (MN1, P9, some MN4) increase their activity to light; others (P7, some MN4) decrease their activity in response to light (Richards and Farley, 1987;Hodgson and Crow, 1991). Of these, MN1 is thought to be the most significant, because stimulation causes movement of the tail, and because it receives polysynaptic excitatory input (via a type 1 interneuron) from type A photoreceptors (Goh and Alkon, 1984).

The first hypothesis regarding the expression of classical conditioning was based on the differences in these motorneurons between paired and randomly trained Hermissenda. The light induced increase in activity of MN1 and P9 is smaller in paired animals (Goh, Lederhendler, and Alkon, 1985;Hodgson and Crow, 1992). Similarly, the light induced decrease in activity of P7 is smaller in paired animals. Prior to conditioning, type A photoreceptors indirectly excite motor neurons, such as MN1, responsible for positive phototaxis (Fig 6, left: gray connections). After conditioning, an increase in excitability of type B photoreceptors leads to an increase in type B to type A photoreceptor inhibition, which leads to a decrease in excitation from type A photoreceptors to MN1 (and P9) motorneurons (Fig 6, right: gray connections), which results in less movement toward the light and delayed phototaxis.

Fig 6.

Information flow from sensory neurons to motorneurons involved in classical conditioning behavior. Polysynaptic connections are indicated by dashed lines. Some of the layer I interneurons have been removed for clarity. T1 indicate the type 1 interneuron described by Goh and Alkon (1984). The change in line thickness on the post-conditioning side of the figure indicates whether the connection has an increase in strength (either due to an increase activity of the pre-synaptic neuron, or an increase in synaptic weight) or a decrease in strength. Pathways are color coded by their effect on motor neurons. Gray: excitation by type A; Green: excitation by type B; Red: disinhibition by type B, becomes stronger with conditioning; Blue: inhibition by type B, becomes stronger with conditioning; Black: UR pathway. The excitation of MN1 and P9 is smaller after classical conditioning. In addition, the increase in inhibition of VP1 and VP2 via the Ie interneuron is stronger than the increase in disinhibition via the IIIi interneuron, resulting in a net decrease in light induced activity of VP1 and VP2 after classical conditioning.

This hypothesis is consistent with the effect of classical conditioning on pedal nerve activity and delayed phototaxis. Locomotion is controlled by four of the six pedal nerves (Richards and Farley, 1987) through which all motorneuron axons travel. The multi-unit pedal nerve activity of control animals increases by about 10-20% during light stimulation; in paired animals, the multi-unit activity increases less (Rogers and Matzel, 1996), or decreases below the dark activity level (Richards and Farley, 1987). These observations are consistent with hypothesis that type B photoreceptors suppress pedal nerve activity via suppression of type A photoreceptors, but do not explain foot contraction that precedes delayed phototaxis.

Ventral motorneurons are involved in classical conditioning behavior

Recently, Crow and colleagues have discovered additional circuits of information flow involved in classical conditioning behavior. They have characterized a second set of motorneurons on the ventral surface of the pedal ganglia, as well as additional interneurons receiving input from statocyst hair cells. VP1 and VP2 are motor neurons located on the ventral surface of the pedal ganglia and are responsible for ciliary movement mediating phototaxis (Crow and Tian, 2003a). VCMN is a foot contraction motorneuron located on the ventral surface of the pedal ganglia. Several interneurons directly and indirectly project to these ventral motorneurons. Firing of both Ii and IIi interneurons is accompanied by an increase in IPSPs in VP1 and VP2, thus these neurons have an indirect inhibitory projection to the ciliary motorneurons. In contrast, firing of the interneuron IIe produces a decrease in IPSPs to VP1 and VP2, implying that IIe is inhibiting a spontaneously active neuron that provides tonic inhibition to VP1 and VP2. Such a neuron may be the IIIi interneuron, which inhibits VP1 and VP2 (Fig 5). All three of these pathways (Fig 6, red connections), produce polysynaptic disinhibition of VP1 and VP2 motorneurons in response to light. Alternatively, the pathway through interneuron Ie is polysynaptic inhibition (Fig 6, blue connections), because firing of interneuron Ie produces an increase in IPSPs to VP1 and VP2. The US pathway is mediated by VCMN, which does not receive input from interneurons that receive polysynaptic inputs from photoreceptors (Crow and Tian, 2004). It receives excitatory input from the spontaneously active Ib interneuron (Fig 5), which is indirectly excited by statocyst hair cells (Fig 6, black connections). Thus, via this pathway, vestibular signals are converted into foot contraction.

Changes in excitability and synaptic connection strength in this network can further explain the change in phototaxis caused by classical conditioning. First, paired training causes facilitation of the monosynaptic PSP measured in type I interneurons, and an increase in light evoked spike activity (Crow and Tian, 2002a). The enhancement of complex EPSPs to interneuron Ie and complex IPSPs to interneuron Ii is partly due to the increase in type B photoreceptor spike frequency, and partly due to the enhancement in intrinsic properties of the interneuron. This enhancement in the Ie light response is propagated through the circuit as an increase in inhibition of VP1 (Crow and Tian, 2003b). Presumably, this enhancement of inhibition is greater than the enhanced disinhibition (caused by the increased type B activity) mediated by the IIe and IIi interneurons. The net result is that prior to pairing, light causes VP1 excitation via disinhibition, whereas after pairing light causes VP1 inhibition. In summary, the change in VP1 response consequent to classical conditioning can explain both the change in pedal nerve multi-unit activity and the change in phototaxis; however, the neural circuitry and information flow that explains the foot contraction in response to light after classical conditioning remains concealed.

Do central pattern generators play a role in Hermissenda?

In other systems, many motor behaviors are controlled by neuronal activity patterns produced by an interconnected sets of interneurons called the central pattern generator (CPG). The CPG activates motorneurons to produce motor behavior; an alteration in the neuronal activity pattern of the CPG transforms the motor behavior (e.g. (Combes, Meyrand, and Simmers, 1999;Nargeot, Baxter, and Byrne, 1999). The pattern may be altered by a change in synaptic inputs, e.g. due to sensory inputs, or neuromodulators, which modify synaptic or ionic channels in CPG neurons (Marder and Calabrese, 1996). For example, in molluscs such as Tritonia and Pleurobranchia, both crawling and escape swimming are produced by central pattern generators (Jing and Gillette, 1999;Popescu and Frost, 2002). The rhythmic motor pattern is switched from crawling to escape swimming by patterns of synaptic inputs from command neurons (Jing and Gillette, 2000).

The periodic burst firing of pedal nerves suggests that Hermissenda locomotion is controlled by central pattern generators homologous to those in Tritonia and Pleurobranchia. The change in photoreceptor spatio-temporal firing pattern caused by classical conditioning may produce a non-linear change in the rhythmic motor pattern from that producing phototaxis to that producing foot contraction. Experiments to fill in the missing connections in Fig 5 may discover such a central pattern generator, and demonstrate for the first time the complete circuitry and activity patterns responsible for classical conditioning behavior.

CONCLUSION

The study of Hermissenda classical conditioning was initiated decades ago in the belief that uncovering the secret to learning and memory had the best chance of success by studying simple learning behaviors in simple animals. Indeed, a body of research convincingly demonstrates that ionic and synaptic channels in photoreceptors are modified during memory storage. Similarly, many of the second messenger pathways activated by CS and US have been delineated. Nonetheless, this review argues that significant gaps in knowledge exist, most notably (but not exclusively) regarding the neural circuitry translating changes in photoreceptor excitability to changes in behavior. The complexity of memory storage mechanisms revealed thus far, and the parallels with mammalian systems, reinforces the imperative to investigate invertebrate learning and memory.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Harold Morowitz for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. The author apologizes to the many authors whose work was not cited; the references had to be limited due to the editor’s discretion. Parts of the research reported in the manuscript was supported by NSF and NIMH.

Biography

Dr. Blackwell received her V.M.D. and Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania and is an associate professor in the School of Computational Sciences and the Krasnow Institute for Advanced Studies at George Mason University. Her research examines the synaptic and ionic currents and second messenger pathways involved in associative learning, using a combination of experimental and computational techniques

References

- 1.Acosta-Urquidi J, Crow T. Differential modulation of voltage-dependent currents in Hermissenda type B photoreceptors by serotonin. J Neurophysiology. 1993;70:541–548. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.2.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkon DL. Cellular analysis of a gastropod (Hermissenda crassicornis) model of associative learning. Biol Bull. 1980a;159:505–560. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkon DL. Membrane depolarization accumulates during acquisition of an associative behavioral change. Science. 1980b;210:1375–1376. doi: 10.1126/science.7434034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkon DL, Anderson MJ, Kuzirian AJ, Rogers DF, Fass DM, Collin C, Nelson TJ, Kapetanovic IM, Matzel LD. GABA-mediated synaptic interaction between the visual and vestibular pathways of Hermissenda. J Neurochem. 1993;61:556–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkon DL, Farley J, Sakakibara M, Hay B. Voltage-dependent calcium and calcium-activated potassium currents of a molluscan photoreceptor. Biophys J. 1984;46:605–614. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84059-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkon DL, Fuortes MGF. Response of photoreceptors in Hermissenda. Journal of General Physiology. 1972;60:631–649. doi: 10.1085/jgp.60.6.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkon DL, Grossman Y. Long-lasting depolarization and hyperpolarization in eye of Hermissenda. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:1328–1342. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.5.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkon DL, Sakakibara M, Forman R, Harrigan J, Lederhendler II, Farley J. Reduction of two voltage-dependant K+ currents mediates retention of a learned association. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1985;44:278–300. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(85)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asaoka Y, Kikkawa U, Sekiguchi K, Shearman MS, Kosaka Y, Nakano Y, Satoh T, Nishizuka Y. Activation of a brain-specific protein kinase C subspecies in the presence of phosphatidylethanol. FEBS Lett. 1988;231:221–224. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80735-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auerbach SB, Grover LM, Farley J. Neurochemical and immunocytochemical studies of serotonin in the Hermissenda central nervous system. Brain Res Bull. 1989;22:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbas D, DesGroseillers L, Castellucci VF, Carew TJ, Marinesco S. Multiple serotonergic mechanisms contributing to sensitization in Aplysia: evidence of diverse serotonin receptor subtypes. Learn Mem. 2003;10:373–386. doi: 10.1101/lm.66103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger TW, Rinaldi PC, Weisz DJ, Thompson RF. Single-unit analysis of different hippocampal cell types during classical conditioning of rabbit nictitating membrane response. J Neurophysiology. 1983;50:1197–1219. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.5.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berridge MJ, Galione A. Cytosolic calcium oscillators. FASEB Journal. 1988;2:3074–3082. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.15.2847949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackwell KT. Calcium waves and closure of potassium channels in response to GABA stimulation in Hermissenda type B photoreceptors. J Neurophysiol. 2002a;87:776–792. doi: 10.1152/jn.00867.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackwell KT. The effect of intensity and duration on the light-induced sodium and potassium currents in the Hermissenda type B photoreceptor. J Neurosci. 2002b;22:4217–4228. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-04217.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackwell KT. Paired turbulence and light do not produce a supralinear calcium increase in Hermissenda. J Comput Neurosci. 2004;17:81–99. doi: 10.1023/B:JCNS.0000023866.88225.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackwell KT, Alkon DL. Ryanodine receptor modulation of in vitro associative learning in Hermissenda crassicornis. Brain Research. 1999;822:114–125. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blair HT, Schafe GE, Bauer EP, Rodrigues SM, LeDoux JE. Synaptic plasticity in the lateral amygdala: a cellular hypothesis of fear conditioning. Learn Mem. 2001;8:229–242. doi: 10.1101/lm.30901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bliss TVP, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckler KJ. Background leak K+-currents and oxygen sensing in carotid body type 1 cells. Respir Physiol. 1999;115:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai Y, Baxter DA, Crow T. Computational study of enhanced excitability in Hermissenda: membrane conductances modulated by 5-HT. J Comput Neurosci. 2003;15:105–121. doi: 10.1023/a:1024479020420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collin C, Ikeno H, Harrigan JF, Lederhendler II, Alkon DL. Sequential modification of membrane currents with classical conditioning. Biophysical Journal. 1988;54:955–960. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83031-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Combes D, Meyrand P, Simmers J. Dynamic restructuring of a rhythmic motor program by a single mechanoreceptor neuron in lobster. J Neuroscience. 1999;19:3620–3628. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03620.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connor J, Alkon DL. Light- and voltage-dependent increases of calcium ion concentration in molluscan photoreceptors. J Neurophysiol. 1984;51:745–752. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coulter DA, Lo Turco JJ, Kubota M, Disterhoft JF, Moore JW, Alkon DL. Classic conditioning reduces amplitude and duration of calcium-dependant afterhyperpolarization in rabbit hippocampal pyramidal cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1989;61:971–981. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cowan TM, Siegel RW. Drosophila mutations that alter ionic conduction disrupt acquisition and retention of a conditioned odor avoidance response. J Neurogenet. 1986;3:187–201. doi: 10.3109/01677068609106849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crow T. Conditioned modification of phototactic behavior in Hermissenda. II. Differential adaptation of B-photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 1985;5:215–223. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-01-00215.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crow T. Pavlovian conditioning of Hermissenda: current cellular, molecular, and circuit perspectives. Learn Mem. 2004;11:229–238. doi: 10.1101/lm.70704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crow T, Alkon DL. Retention of an associative behavioral change in Hermissenda. Science. 1978;201:1240–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.694512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crow T, Alkon DL. Associative behavioral modification in Hermissenda: cellular correlates. Science. 1980;209:412–414. doi: 10.1126/science.209.4454.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crow T, Bridge MS. Serotonin modulates photoresponses in Hermissenda type-B photoreceptors. Neurosci Lett. 1985;60:83–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crow T, Forrester J. Light paired with serotonin mimics the effect of conditioning on phototactic behavior of Hermissenda. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:7975–7978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crow T, Forrester J, Williams M, Waxham MN, Neary JT. Down-regulation of protein kinase C blocks 5-HT-induced enhancement in Hermissenda B photoreceptors. Neurosci Lett. 1991;121:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90660-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crow T, Tian LM. Facilitation of monosynaptic and complex PSPs in type I interneurons of conditioned Hermissenda. J Neuroscience. 2002a;22:7818–7824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07818.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crow T, Tian LM. Morphological characteristics and central projections of two types of interneurons in the visual pathway of Hermissenda. J Neurophysiol. 2002b;87:322–332. doi: 10.1152/jn.00319.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crow T, Tian LM. Interneuronal projections to identified cilia-activating pedal neurons in Hermissenda. J Neurophysiol. 2003a;89:2420–2429. doi: 10.1152/jn.01047.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crow T, Tian LM. Neural correlates of Pavlovian conditioning in components of the neural network supporting ciliary locomotion in Hermissenda. Learn Mem. 2003b;10:209–216. doi: 10.1101/lm.58603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crow T, Tian LM. Statocyst hair cell activation of identified interneurons and foot contraction motor neurons in Hermissenda. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:2874–2883. doi: 10.1152/jn.00028.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ, Siddiqi V, Kang Y, Neary JT. Phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by one-trial and multi-trial classical conditioning. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3480–3487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03480.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ, Siddiqi V, Neary JT. Serotonin activation of the ERK pathway in Hermissenda: contribution of calcium-dependent protein kinase C. J Neurochem. 2001;78:358–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daoudal G, Debanne D. Long-term plasticity of intrinsic excitability: learning rules and mechanisms. Learn Mem. 2003;10:456–465. doi: 10.1101/lm.64103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Detwiler PB. Multiple light-evoked conductance changes in the photoreceptors of Hermissenda crassicornis. J Physiol. 1976;256:691–708. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Detwiler PB, Fuortes MG. Responses of hair cells in the statocyst of Hermissenda. J Physiol. 1975;251:107–129. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donnelly DF. K+ currents of glomus cells and chemosensory functions of carotid body. Respir Physiol. 1999;115:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farley J, Auerbach S. Protein kinase C activation induces conductance changes in Hermissenda photoreceptors like those seen in associative learning. Nature. 1986;319:220–223. doi: 10.1038/319220a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farley J, Han Y. Ionic basis of learning-correlated excitability changes in Hermissenda type A photoreceptors. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1861–1888. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farley J, Richards WG, Grover LM. Associative learning changes intrinsic to Hermissenda type A photoreceptors. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1990;104:135–152. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farley J, Wu R. Serotonin modulation of Hermissenda type B photoreceptor light responses and ionic currents: implications for mechanisms underlying associative learning. Brain Res Bull. 1989;22:335–351. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flynn M, Cai Y, Baxter DA, Crow T. A computational study of the role of spike broadening in synaptic facilitation of Hermissenda. J Comput Neurosci. 2003;15:29–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1024418701765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fost JW, Clark GA. Modeling Hermissenda: I. Differential contributions of IA and IC to type-B cell plasticity. J Comput Neurosci. 1996a;3:137–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00160809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fost JW, Clark GA. Modeling Hermissenda: II. Effects of variations in type-B cell excitability, synaptic strength, and network architecture. J Comput Neurosci. 1996b;3:155–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00160810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frysztak RJ, Crow T. Differential expression of correlates of classical conditioning in identified medial and lateral type A photoreceptors of Hermissenda. J Neuroscience. 1993;13:2889–2897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frysztak RJ, Crow T. Synaptic enhancement and enhanced excitability in presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons in the conditioned stimulus pathway of Hermissenda. J Neuroscience. 1997;17:4426–4433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04426.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gandhi CC, Matzel LD. Modulation of presynaptic action potential kinetics underlies synaptic facilitation of type B photoreceptors after associative conditioning in Hermissenda. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:2022–2035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-02022.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goh Y, Alkon DL. Sensory, interneuronal, and motor interactions within Hermissenda visual pathway. J Neurophysiology. 1984;52:156–169. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.52.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goh Y, Lederhendler I, Alkon DL. Input and output changes of an identified neural pathway are correlated with associative learning in Hermissenda. J Neuroscience. 1985;5:536–543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-02-00536.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hall JF. Classical conditioning and instrumental learning: a contemporary approach. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hirabayashi T, Kume K, Hirose K, Yokomizo T, Iino M, Itoh H, Shimizu T. Critical duration of intracellular Ca2+ response required for continuous translocation and activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5163–5169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hodgson TM, Crow T. Characterization of 4 light-responsive putative motor neurons in the pedal ganglia of Hermissenda crassicornis. Brain Res. 1991;557:255–264. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90142-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hodgson TM, Crow T. Cellular correlates of classical conditioning in identified light responsive pedal neurons of Hermissenda crassicornis. Brain Res %20. 1992;570:267–271. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ito E, Oka K, Collin C, Schreurs BG, Sakakibara M, Alkon DL. Intracellular calcium signals are enhanced for days after Pavlovian conditioning. J Neurochem. 1994;62:1337–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jing J, Gillette R. Central pattern generator for escape swimming in the notaspid sea slug Pleurobranchaea californica. J Neurophysiology. 1999;81:654–667. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jing J, Gillette R. Escape swim network interneurons have diverse roles in behavioral switching and putative arousal in Pleurobranchaea. J Neurophysiology. 2000;83:1346–1355. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kandel ER, Pittenger C. The past, the future and the biology of memory storage. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:2027–2052. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Land PW, Crow T. Serotonin immunoreactivity in the circumesophageal nervous system of Hermissenda crassicornis. Neurosci Lett. 1985;62:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lefebvre L, Reader SM, Sol D. Brains, innovations and evolution in birds and primates. Brain Behav Evol. 2004;63:233–246. doi: 10.1159/000076784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lester DS, Collin C, Etcheberrigaray R, Alkon DL. Arachidonic acid and diacylglycerol act synergistically to activate protein kinase C in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179:1522–1528. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malinow R, Malenka RC. AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marder E, Calabrese RL. Principles of rhythmic motor pattern generation. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:687–717. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matzel LD, Rogers RF. Postsynaptic calcium, but not cumulative depolarization, is necessary for the induction of associative plasticity in Hermissenda. J Neurosci. 1993;13:5029–5040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05029.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matzel LD, Talk AC, Muzzio IA, Rogers RF. Ubiquitous molecular substrates for associative learning and activity-dependent neuronal facilitation. Rev Neurosci. 1998;9:129–167. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1998.9.3.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mo JL, Blackwell KT. Comparison of Hermissenda type A and type B photoreceptors: response to light as a function of intensity and duration. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8020–8028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-08020.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moyer JR, Jr, Thompson LT, Disterhoft JF. Trace eyeblink conditioning increases CA1 excitability in a transient and learning-specific manner. J Neuroscience. 1996;16:5536–5546. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05536.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Muzzio IA, Gandhi CC, Manyam U, Pesnell A, Matzel LD. Receptor-stimulated phospholipase A(2) liberates arachidonic acid and regulates neuronal excitability through protein kinase C. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1639–1647. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.4.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muzzio IA, Talk AC, Matzel LD. Incremental redistribution of protein kinase C underlies the acquisition curve during in vitro associative conditioning in Hermissenda. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1997;111:739–753. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.4.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muzzio IA, Talk AC, Matzel LD. Intracellular Ca2+ and adaption of voltage responses to light in Hermissenda photoreceptors. NeuroReport. 1998;9:1625–1631. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199805110-00067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nargeot R, Baxter DA, Byrne JH. In vitro analog of operant conditioning in Aplysia. II. Modifications of the functional dynamics of an identified neuron contribute to motor pattern selection. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:2261–2272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02261.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neary JT, Crow T, Alkon DL. Change in a specific phosphoprotein band following associative learning in Hermissenda. Nature. 1981;293:658–660. doi: 10.1038/293658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oancea E, Meyer T. Protein kinase C as a molecular machine for decoding calcium and diacylglycerol signals. Cell. 1998;95:307–318. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81763-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Popescu IR, Frost WN. Highly dissimilar behaviors mediated by a multifunctional network in the marine mollusk Tritonia diomedea. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1985–1993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01985.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rankin CH. Invertebrate learning: what can’t a worm learn? Curr Biol. 2004;14:R617–R618. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Richards WG, Farley J. Motor correlates of phototaxis and associative learning in Hermissenda crassicornis. Brain Res Bull. 1987;19:175–189. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rogers RF, Matzel LD. G-Protein mediated responses to localized serotonin application in a invertebrate photoreceptor. NeuroReport. 1995;6:2161–2165. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199511000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rogers RF, Matzel LD. Higher-order associative processing in Hermissenda suggests multiple sites of neuronal modulation. Learn Mem. 1996;2:279–298. doi: 10.1101/lm.2.6.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sakakibara M, Ikeno H, Usui S, Collin C, Alkon DL. Reconstruction of ionic currents in a molluscan photoreceptor. Biophys J. 1993;65:519–527. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81068-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sakakibara M, Inoue H, Yoshioka T. Evidence for the involvement of inositol trisphosphate but not cyclic nucleotides in visual transduction in Hermissenda eye. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20795–20801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schreurs BG, Alkon DL. Imaging learning and memory: classical conditioning. Anat Rec. 2001;265:257–273. doi: 10.1002/ar.10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schreurs BG, Gusev PA, Tomsic D, Alkon DL, Shi T. Intracellular correlates of acquisition and long-term memory of classical conditioning in Purkinje cell dendrites in slices of rabbit cerebellar lobule HVI. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:5498–5507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05498.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schuman EM, Clark GA. Synaptic facilitation at connections of Hermissenda type B photoreceptors. J Neuroscience. 1994;14:1613–1622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01613.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shinomura T, Asaoka Y, Oka M, Yoshida K, Nishizuka Y. Synergistic action of diacylglycerol and unsaturated fatty acid for protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5149–5153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shors TJ, Matzel LD. Long-term potentiation: what’s learning got to do with it? Behavioral & Brain Sciences. 1997;20:597–614. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x97001593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Squire LR, Zola SM. Structure and function of declarative and nondeclarative memory systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13515–13522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stensaas LJ, Stensaas SS, Trujillo-Cenoz O. Some morphological aspects of the visual system of Hermissenda crassicornis (Mollusca: Nudibranchia) J Ultrastruct Res. 1969;27:510–532. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)80047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sweatt JD. The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Talk AC, Matzel LD. Calcium influx and release from intracellular stores contribute differentially to activity-dependent neuronal facilitation in Hermissenda photoreceptors. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1996;66:183–197. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Talk AC, Muzzio IA, Matzel LD. Phospholipases and arachidonic acid contribute independently to sensory transduction and associative neuronal facilitation in Hermissenda type B photoreceptors. Brain Res. 1997;751:196–205. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Teyler TJ, DiScenna P. Long-term potentiation as a candidate mnemonic device. Brain Res. 1984;319:15–28. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(84)90027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Warren RA, Agmon A, Jones EG. Oscillatory synaptic interactions between ventroposterior and reticular neurons in mouse thalamus in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1993–2003. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Werness SA, Fay SD, Blackwell KT, Vogl TP, Alkon DL. Associative learning in a network model of Hermissenda crassicornis. II. Experiments. Biol Cybern. 1993;69:19–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00201405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.White JA, Banks MI, Pearce RA, Kopell N. Networks of interneurons with fast and slow gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) kinetics provide substrate for mixed gamma-theta rhythm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8128–8133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100124097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Windholz G. The discovery of the principles of reinforcement, extinction, generalization, and differentiation of conditional reflexes in Pavlov’s laboratories. Pavlov J Biol Sci. 1989;24:35–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02964534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yamoah EN, Matzel L, Crow T. Expression of different types of inward rectifier currents confers specificity of light and dark responses in type A and B photoreceptors of Hermissenda. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6501–6511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06501.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]