Abstract

Attachment of tumor cells to the endothelium (EC) under flow conditions is critical for the migration of tumor cells out of the vascular system to establish metastases. Innate immune system processes can potentially promote tumor progression through inflammation dependant mechanisms. White blood cells, neutrophils (PMN) in particular, are being studied to better understand how the host immune system affects cancer cell adhesion and subsequent migration and metastasis. Melanoma cell interaction with the EC is distinct from PMN-EC adhesion in the circulation. We found PMN increased melanoma cell extravasation, which involved initial PMN tethering on the EC, subsequent PMN capture of melanoma cells and maintaining close proximity to the EC. LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18 integrin) influenced the capture phase of PMN binding to both melanoma cells and the endothelium, while Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18 integrin) affected prolonged PMN-melanoma aggregation. Blocking E-selectin or ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule) on the endothelium or ICAM-1 on the melanoma surface reduced PMN-facilitated melanoma extravasation. Results indicated a novel finding that PMN-facilitated melanoma cell arrest on the EC could be modulated by endogenously produced interleukin-8 (IL-8). Functional blocking of the IL-8 receptors (CXCR1 and CXCR2) on PMN, or neutralizing soluble IL-8 in cell suspensions, significantly decreased the level of Mac-1 up-regulation on PMN while communicating with melanoma cells and reduced melanoma extravasation. These results provide new evidence for the complex role of hemodynamic forces, secreted chemokines, and PMN-melanoma adhesion in the recruitment of metastatic cancer cells to the endothelium in the microcirculation, which are significant in fostering new approaches to cancer treatment through anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Keywords: Cancer, Immunoediting, Adhesion molecules, Chemokines, Signaling, Endothelium, Shear stress, Adhesion and migration

1 Introduction

It has become evident from in vivo studies (Chambers et al., 2000; Liotta, 1992; Scherbarth and Orr, 1997; Zetter, 1993) that the mechanisms utilized by leukocytes and metastatic tumor cells to adhere to a vessel wall prior to extravasation are very different. Human leukocytes, including neutrophils (PMN), actively participate in the inflammatory response via adhesion to vascular endothelium (Harlan and Liu, 1992; Lauffenburger and Linderman, 1993; Smith et al., 1989). Detailed studies of cell-cell interactions suggest that selectins are required for the initial rolling of leukocytes on activated endothelium. L-selectin and Sialyl Lewis X (SLe X) on leukocytes and E- and P-selectin on endothelial cells (EC) participate in these interactions (Lawrence and Springer, 1991; Ley et al., 1995). Stronger binding mediated by β2 integrins expressed on the leukocyte (Mac-1 or LFA-1) and ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule) on the endothelial cells is responsible for prolong shear-resisted attachment (Springer, 1994). Recent studies have suggested that LFA-1 to ICAM-1 adhesion is important in initial endothelial capture of PMN, while Mac-1 and ICAM-1 interaction forms shear-resisted bonds to stabilize PMN-endothelium adhesion (Hentzen et al., 2000; McDonough et al., 2004; Neelamegham et al., 1998).

Several ligands for inducible endothelial adhesion molecules have been identified on various types of tumor cells (Yamada, 1993). For example, molecules containing the SLe X determinant, which is the ligand for E-selectin on endothelium, are abundantly expressed on human gastric or colon carcinoma cells (Zetter, 1993). Integrin α4β1 molecules are expressed on RAW117 lymphoma cells, which interact with VCAM-1 (vascular adhesion molecule) expressed on hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells (Papadimitriou et al., 1999). Miele et al. (1994) reported that a dose- and time-dependent increase in surface expression of ICAM-1 was found in human malignant melanoma cells. They also found that inhibiting ICAM-1 reduced melanoma lung metastasis in vivo. All these studies have supported an adhesive mechanism between tumor cells and the endothelium, rather than a simple mechanical entrapment such as vessel-size restriction.

How do tumor cells bind EC? Several studies have focused on the ability of lymphocytes (Kripke, 1994), natural killer cells (Hanna, 1985), T-cells (Willimsky and Blakenstein, 2005) and monocyte/macrophages (Key, 1983; Mantovani, 1994; van Netten et al., 1993; Pollard, 2004) to mediate tumor cell binding and affect tumor progression (Dunn et al., 2002). In particular, human PMN, which comprise 50–70% of circulating leukocytes and are usually cytotoxic to tumor cells, have been shown under certain circumstances to promote tumor adhesion and transendothelial migration (Wu et al., 2001; Slattery and Dong, 2003). An interesting study showed that PMN and activated macrophages increased the ability of rat hepatocarcinoma cells to adhere to an endothelial monolayer (Starkey et al., 1984). In addition, tumor-elicited PMN, in contrast to normal PMN, were found to enhance metastatic potential and invasiveness of rat mammary adenocarcinoma cells in an in vivo tumor-bearing rat model (Welch et al., 1989). Using light and electron microscopy, circulating PMN were discovered in close association with metastatic tumor cells including at the time of tumor cell arrest (Crissman et al., 1985). Although these studies have clearly suggested that the immune system, and PMN in particular, could enhance tumor cell metastasis, there is little understanding of the mechanisms involved (Burdick et al., 2001; Coussens and Werb, 2002; Liotta and Kohn, 2001).

Although several cytokines and chemokines have been implicated in influencing adhesive properties of transformed cells, interleukin 8 (IL-8) is of particular interest. IL-8 has a wide range of pro-inflammatory effects, which mediate PMN migration from the circulation to sites of injury via activation of CXC chemokine receptors 1 and 2 (CXCR1 and CXCR2) on PMN (Walz et al., 1987; Murphy and Tiffany, 1991; Holmes et al., 1991). IL-8 secretion is also a marker for increasing metastatic potentials, e.g., as an important promoter for melanoma growth (Schadendorf et al., 1995; Singh and Varney, 1998). IL-8 could potentially enhance PMN binding to melanoma cells and the endothelium (Singh et al., 1999). Chemokines or cytokines secreted by tumor cells and PMN may play an important role in communication between tumor cells and PMN and affect the interactions between them as well (Fredrick and Clayman, 2001). However, how those chemokine expressions are regulated in a tumor microenvironment and what roles those upregulated chemokines play in mediating tumor cell extravasation within the circulation are not known.

The objectives of this paper are to apply novel in vitro flow and migration assays and delineate mechanisms possibly involved in PMN-mediated melanoma extravasation under the influence of hydrodynamic forces, chemokine up-regulation and melanoma-leukocyte-endothelial adhesion. We conclude that PMN-facilitated melanoma cell arrest on the endothelium and subsequent melanoma trans-endothelial migration are regulated by β2 integrins/ICAM-1 adhesion and modulated by endogenously produced IL-8. These findings are significant in fostering new approaches to cancer treatment through anti-inflammatory therapeutics (Homey et al., 2002).

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents

Type IV collagen was purchased from BD Discovery Labware (Bedford, MA). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), human serum albumin (HSA) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were all purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Recombinant human IL-8 protein, mouse anti-human IL-8, mouse anti-human E-selectin, and mouse anti-human CXCR1/CXCR2 mAbs were purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). Mouse anti-human CD11a, mouse anti-human CD11b, and mouse anti-human ICAM-1 were purchased from CalTag (Burlingame, CA).

2.2 Cell Culture and Choice of Melanoma Cell Lines

We utilized three different human melanoma cell lines (Table 1), to correlate tumor metastatic potentials with melanoma cell invasiveness, chemotactic migration and adhesiveness. “Metastatic” potential was qualitatively determined from the cell line origin; “Chemotactic” potential was measured by cell static migration toward soluble type IV collagen (CIV; 100μg/ml) using Boyden chamber; and “Adhesion” potential was quantified by comparing relative mean fluorescence levels of ICAM-1 expression obtained by flow cytometry. We also used non-metastatic primary human melanocyte (BioWhittaker/Clonetics, CA) as a control.

Table 1.

Choice of Melanoma Cell Lines

| Cell line | Potentials | Reference: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic | Chemotactic (CIV) | Adhesion (ICAM-1) | ||

| WM 9 | ++ | +++ | +++ | www.wistar.upenn.edu/herlyn/melcell.htm |

| C8161 | +++ | +++ | ++ | Int J Cancer 47:227, 1991. |

| WM35 | − | + | + | www.wistar.upenn.edu/herlyn/melcell.htm |

C8161.c9, WM9 and WM35 melanoma cells were maintained and prepared as described previously (Welch et al. 1991; Liang et al., 2005). NHEM (melanocytes) were maintained in culture according to the manufacturer’s suggested protocol (Slattery and Dong, 2003). Prior to each experiment, melanoma cells were detached when nearly confluent and suspended at a concentration of 1×106cells/ml. In assays where anti-ICAM-1 blocking antibodies were used, cells were incubated with mAb (5 μl/ml) for 30 minutes at 37°C prior to the start of an assay. IgG isotype control antibody was used to verify specificity of all blocking antibodies.

EI cells are cells that had been transfected from fibroblast L-cells to express human E-selectin and ICAM-1, which were grown in tissue culture to a monolayer as described elsewhere (Simon et al., 2000). EI cells were used in this study as a substrate for cell adhesion and as a model of an “endothelial monolayer”. E-selectin and ICAM-1 levels were periodically checked by flow cytometry to verify expression level. ICAM-1 levels on EI cells were shown to be comparable with IL-1β stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Gopalan et al., 1997). For some adhesion receptor blocking assays, the confluent EI monolayer was treated with anti-ICAM-1 mAb (5 μg/106 cells) or anti-E-selectin mAb (5 μg/106 cells).

2.3 Neutrophil Isolation and Preparation

Fresh blood was obtained from healthy adults following a Penn State Institutional Review Board approved protocol. Histopaque® gradient (Sigma) was used to isolate and enrich the PMN population. The isolated PMN layer was first suspended in 0.1% HSA in DPBS and washed. ACK lysis buffer (0.15M NH4Cl, 10.0mM KHCO3, 0.1mM Na2EDTA in distilled H2O) was used to remove erythrocytes. The cells were washed with 0.1%HSA/DPBS, resuspended at a concentration of 1×106cells/ml and rocked at 4 °C until they were used, no longer than 4 hours. To activate LFA-1 or Mac-1 on PMN, cells were treated with PMA (100ng/ml, 20 min) or IL-8 (1ng/ml, 1 hr) respectively. PMA was not found to affect Mac-1 expression on PMN (data not shown). In blocking assays, PMN were treated with saturating concentrations of antibodies, 5μg of anti-human CD11a or CD11b per 1×106 cells, in blocking buffer (5% calf serum, 2% goat serum in DPBS) for 30 minutes at 4 ° C. Similarly, to block IL-8 receptors, PMN were treated with mouse anti-human CXCR1 and CXCR2 antibodies with 6μg/ml and 10μg/ml, respectively, in blocking buffer for 30 minutes at 4 °C.

2.4 Flow Migration Assay

The in vitro flow-migration device (Fig. 1, top right) is a recently developed modified 48-well chemotactic Boyden chamber (Dong et al., 2002). In brief, the top and bottom plates of the polycarbonate chamber are separated by a 0.02 inch-thick silicon gasket (PharmElast, SF Medical, Hudson, MA). A 7cm × 2cm opening cut from the center of the gasket forms the flow field. The wall shear stress (τw) is related to the volumetric flow rate (Q) by τw=6μQ/wh2, where μ is the fluid viscosity, h is height and w is width of the flow field.

Figure 1.

Schematic of PMN-facilitated melanoma adhesion to the EC in a shear flow. Top left: a melanoma cell in close proximity to the EC via a tethered PMN. Melanoma cells are captured by tethered PMN on the EC via β2 integrins/ICAM-1 interactions. Top right: cross-section view of the flow-migration chamber. Bottom: representative aggregation of melanoma cells (TC) to tethered PMN on an endothelial monolayer. Flow direction is from left to right: (A) a melanoma cell and a PMN on the monolayer at 0 second; (B) collision between a PMN and a melanoma cell after 20 seconds; and (C) arrest of a melanoma cell to the monolayer due to the formation of PMN-melanoma aggregates after 30 seconds.

An endothelial monolayer was formed by growing EI cells to confluence on sterilized PVP-free polycarbonate filters (8-μm pore size; NeuroProbe, Gaithersburg, MD) coated with fibronectin (30μg/ml, 3 hr) (Sigma). The bottom side of the filter was scraped prior to use to remove any potential cell growth. Soluble type IV collagen (CIV; 100μg/ml in RPMI 1640/0.1%BSA) (Aznavoorian et al. 1990; Hodgson and Dong, 2001) was used as the chemoattractant in the center 12 wells and control wells were filled with medium (RPMI 1640/0.1%BSA). The chamber was assembled and the cells were then introduced into the chamber. Typical experiments involved cases such as: PMN only; melanoma cells (C8161, WM9, or WM35) only; PMN + selected-type melanoma cells; 5×105 cells of each cell type. Flow of circulating medium was immediately perfused into the chamber, initially at a flow rate 2 ml/min, which was then increased to a desired experimental rate (0–20 ml/min). The entire chamber was placed in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 4 hours.

To quantify migration, the filter was removed from the chamber and immediately stained with HEMA-3 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The cells on the bottom side of each filter, the side that had been facing the chemoattractant wells, were imaged using an inverted microscope and recorded with NIH Image (v. β4.0.2). No cells were found in the chemoattractant wells after 4 hours of migration (Slattery and Dong, 2003; Slattery et al., 2005). Three pictures were taken of each filter in different locations. The number of cells migrated was quantified and averaged for each filter. A minimum of three filters were analyzed for each data point. Background migration was subtracted from each sample as appropriate.

2.5 Parallel Plate Flow Assay

Cell collision and adhesion experiments were performed in a parallel-plate flow chamber (Glycotech, Rockville, MD) mounted on the stage of a phase-contrast optical microscope (Diaphot 330, Nikon, Japan). A syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA) was used to generate a steady flow field in the flow chamber. A petri dish (35 mm) with a confluent EI cell monolayer was attached to the flow chamber by vacuum and placed on the inverted microscope. All experiments were performed at 37°C. Flow experiments were recorded and the field of view was 800 μm long (direction of the flow) by 600 μm. The focal plane was set on the endothelial monolayer (Fig. 1, bottom). The flow chamber was perfused with appropriate media over the endothelial monolayer for 2–3 minutes at a shear rate of 40 sec−1 for equilibration before the introduction of cells. A typical flow experiment involved perfusion of 106/ml PMN and 106/ml selected-type melanoma cells. After allowing cells to contact the endothelial monolayer at a shear stress of 0.1–0.3 dyn/cm2 for 2 min to promote interactions with the monolayer, the shear stresses was adjusted to a desired experimental rate and kept constant for 6–7 minutes. Experiments were performed in triplicate and analyzed offline.

2.6 PMN Tethering Frequencies

The tethering frequency was determined experimentally as the number of PMN that adhered to the endothelial monolayer per unit time and area in the parallel-plate flow chamber assay (Fig. 1, bottom), including both rolling and firmly-arrested cells. This frequency was normalized by cell flux to the surface to compensate for the different concentration of cells passing the same area of substrate at different shear rates. This normalization followed the procedure of Rinker et al. (2001) based on equations derived by Munn et al. (1994).

2.7 Melanoma-PMN Aggregation and Adhesion Efficiency Analysis

Melanoma-PMN aggregation on the surface of an endothelial monolayer was analyzed by a parallel-plate flow assay. Quantification started at the onset of experimental shear rate (t = 0 min) and lasted for 5 min. Aggregates could be characterized by differences in cell sizes and velocities (Fig. 1, bottom). Aggregation variables to be quantified included the total number of PMN which were tethered (rolling or arrested) on the endothelial monolayer; collisions of melanoma cells (from the free stream near the endothelium) to tethered PMN; aggregation of melanoma with tethered PMN as a result of the collision; and final attachment of melanoma-PMN aggregates on the endothelial monolayer. For some cases in which more than one melanoma cell adhered to a PMN, we count such a case as two aggregates if two melanoma cells adhered to a PMN.

2.8 Melanoma Cell Adhesion Efficiency

“Melanoma adhesion efficiency” can be expressed by the following ratio:

The numerator is the number of melanoma cells arrested on the endothelial monolayer at the end of the entire flow assay as a result of collision between entering melanoma cells and tethered PMN. The denominator is the total number of melanoma-PMN collisions near the endothelial monolayer surface and is counted as a transient accumulative parameter throughout the entire flow assay.

2.9 Co-Culture of PMN and Melanoma cells

Selected-type melanoma cells were cultured in 6-well plates (Corning). PMN (5×106 per well), untreated or treated with anti-CXCR1 and CXCR2 antibodies (as described above), were added to each well either directly in contact with the melanoma cell monolayer or into a Transwell insert (0.4 μm pore; Corning) above the monolayer. As a control, PMN were concurrently cultured in plates without melanoma cells. The plates were then incubated for 4 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 4 hours, the cell or supernatant samples were prepared for further analysis by either flow cytometry, ELISA or immunoblot (see descriptions below).

2.10 Cell Adhesion Molecule Expressions (Flow Cytometry)

Cells of interest were treated with murine anti-human CD marker primary antibodies (e.g., anti-LFA-1, anti-Mac-1, or anti-ICAM-1; 1μg Ab/106 cells) for 30 minutes at 4 ° C. The cells were then treated with secondary anti-body, FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab)2 fragment (1μg/106 cells) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 25 minutes at 4 ° C. In the case of blocking CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors on PMN, PE-conjugated anti-Mac-1 (1μl/106 cells; CalTag Laboratories) was used to avoid binding secondary antibody to the existing CXCR1 and CXCR2 antibodies. The specimens were washed again, fixed with 2% formaldehyde, and analyzed by GUAVA personal cytometer (GUAVA Technologies Inc., Burlingame, CA). As a control, background fluorescence was assessed using cells treated with secondary antibodies only or PE-conjugated isotype control.

2.11 Detection of IL-8 from Melanoma-PMN Co-Culture (ELISA)

Enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) detection of protein secretion was performed at the Penn State NIH Cytokine Core Facility. Samples were prepared from supernatant of cultured cells. Approximately 1×106 cells, as counted using hemacytometer, were cultured in fresh medium for 4 hr. All supernatant samples were spun at 1500 rpm for 5 min to remove debris and stored at −80 ° C prior to analysis. In the cases of PMN and melanoma cell co-culture, the 2 cell types (~1×106 each) were cultured together in a 6 well plate (BD Biosciences) either directly in contact or with Transwell inserts on top, where melanoma cells were separated from PMN during the 4 hours co-culture.

2.12 Detection of Intracellular IL-8 Expression (Immunoblot)

Whole cell extracts were prepared from the cells co-cultured with Transwell inserts by resuspending cells in 40μl of lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 2mM Na3VO3, 10mM NaF, 10mM Na4P2O7, 1 % NP-40, 1mM PMSF, 2ng/ml pepstatin A). Lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min followed by a centrifugation at 16,000 g for 1 min at 4 °C. The pellet was discarded and the supernatant was mixed with 2×SDS running buffer (0.2% bromophenol blue, 4% SDS, 100mM Tris [pH 6.8], 200mM DTT, 20% glycerol) in 1:1 ratio. Samples were boiled for 3 min and 15μl was loaded onto a 15% SDS-PAGE gel and proteins were transferred to a 0.2μm PVDF membrane (Millipore Co., Billerica, MA) by electroblotting. Primary antibodies included rabbit anti-human IL-8 (Biosource, Inc.) and anti-β-actin IgG1 (Sigma Chemical Co.). Secondary antibodies were peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG. Proteins were detected using the Enhanced Chemiluminescence Detection System (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Arlington Heights, IL).

2.13 Statistical Analysis

All results are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) unless otherwise stated. One-way ANOVA analysis was used for multiple comparisons and t-tests were used for comparisons between 2 groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3 Results

3.1 Adhesion Molecule Expressions on Melanoma and EI Cells

Flow cytometry was used to detect expression of cell surface adhesion molecule expressions. We did not find detectable Mac-1, LFA-1 and SLe X expressions on all three-type melanoma cells tested, whereas significant ICAM-1 expression was found, especially on C8161 and WM9 cells (Table 1). The expression level usually remains stable over at least 4 hours (data not shown). Stable expressions of E-selectin and ICAM-1 were also confirmed on EI cells.

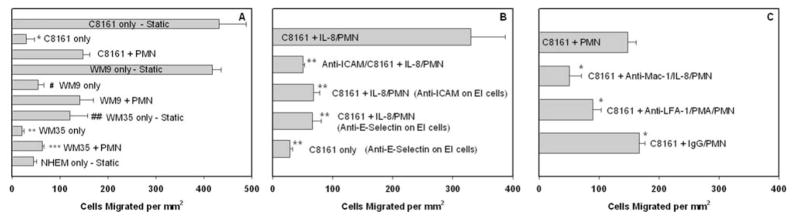

3.2 PMN-facilitated Melanoma Cell Extravasation under Flow Conditions

Melanoma cell chemotactic migration in response to type IV collagen (CIV) (100μg/ml) was characterized using the flow-migration chamber under both static and flow conditions. As a negative control, non-metastatic melanocyte migration was first tested under the static condition toward CIV and found to be near or at a background level (Fig. 2A, bottom). In comparison, highly-metastatic C8161 and WM9 cells were more actively migratory under the no-flow condition than low-metastatic WM35 cells (Fig. 2A, “Static”). When exposed to a shear flow (~0.4 dyn/cm2), extravasations of C8161, WM9 and WM35 cells toward CIV were all significantly less than those under static conditions (Fig. 2A), at a level similar to the melanocyte case. Addition of PMN to the melanoma cell suspension significantly enhanced tumor cell extravasation under shear stress compared with melanoma cells only (all P values < 0.05). Obviousely, tumor metastatic potential correlates with melanoma cell extravasation behavior.

Figure 2.

PMN facilitate melanoma cell migration through an adhesion-mediated mechanism. (A) PMN affect C8161, WM9 and WM35 cell migration under shear conditions. NHEM, which are non-cancerous melanocytes used as a negative control, migrate at a low-threshold level even under the static condition. All cases were under a flow shear stress at 0.4 dyn/cm2, unless labeled “Static” (*P < 0.01 with respect to C8161 static case; #P < 0.05 with respect to WM9 static case; **P < 0.01 with respect to WM35 static case; ##P < 0.05 with respect to both C8161 and WM9 static cases; and ***P < 0.02 with respect to both C8161+PMN and WM9+PMN cases). (B) ICAM plays an important role in PMN-facilitated melanoma cell migration. The second bar shows disrupting C8161-PMN aggregation by blocking ICAM-1 on melanoma significantly reduces melanoma cell migration (PMN were activated by IL-8). The third and fourth bars show inhibiting IL-8-stimulated PMN adhesion to the endothelium by blocking E-selectin or ICAM-1 on the monolayer also decreases C8161 cell migration (**P < 0.01 with respect to C8161+IL-8/PMN case at 0.4 dyn/cm2). (C) Differential role of LFA-1 and Mac-1 on PMN. Both Mac-1 and LFA-1 (to lesser degree) contribute to PMN-mediated melanoma extravasation. The last bar shows migration with isotype antibody-treated PMN, as a control (*P < 0.05 with respect to C8161+PMN case at 0.4 dyn/cm2). All the values are mean ± S.E.M. for N ≥ 3.

Figure 2B–C indicates that each binding step between the triad of the endothelium, PMN and melanoma cell affects tumor cell extravasation under flow conditions. ICAM-1 was functionally blocked on the C8161 cells and EI cells, respectively. Both anti-ICAM/C8161 and anti-ICAM/EI cases significantly reduced melanoma extravasations. Blocking E-selectin on the endothelial cells reduced C8161 melanoma cell migration by 80% compared with the C8161 + IL-8/PMN case (Fig. 2B). However, blocking E-selectin on the EI cells without PMN did not really change melanoma extravasation (Fig. 2B, bottom).

Receptor-ligand binding via β2 integrins (on PMN) and ICAM-1 (on melanoma cells) has been implicated in mediating PMN-melanoma adhesion under flow conditions (Fig. 1). To investigate this mechanism further, melanoma cell extravasations were assayed in the presence of PMN, in which LFA-1 and Mac-1 on PMN were inhibited with functional blocking antibodies. Blocking CD11b resulted in the greatest reduction in C8161 migration (66% reduction as compared to C8161+PMN under 0.4 dyn/cm2 shear stress; Fig. 2C). Similar results are shown in Figure 2C; migration of melanoma cells was decreased by 40% in the presence of CD11a-blocked PMN.

Collectively, results shown in Figure 2 provide new evidence for the complex role of hemodynamic forces and PMN in the recruitment of metastatic cancer cells to the endothelium. PMN-melanoma adhesion and PMN-endothelium adhesion differentially affect PMN-facilitated melanoma migration under flow conditions, specifically via interactions of ICAM-1 and β2-integrins.

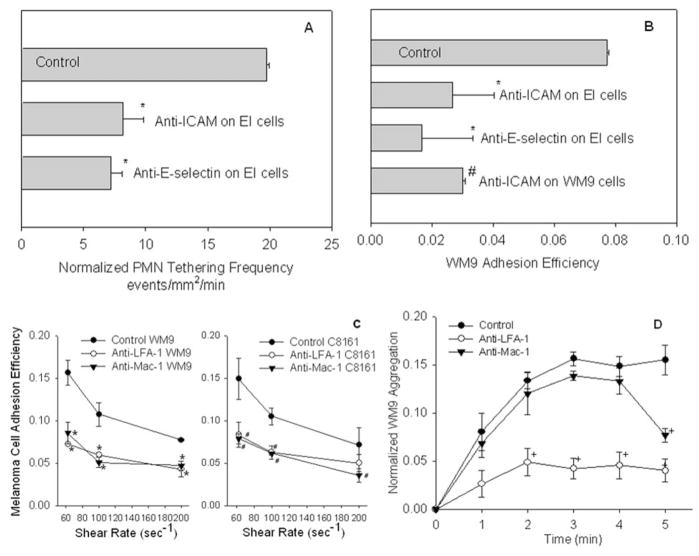

3.3 Relative Role of PMN-EC and PMN-Melanoma Adhesion in Melanoma Cell Arrest

EI cells which express endothelial E-selectin and ICAM-1 adhesion molecules were treated with mouse anti-human E-selectin and anti-ICAM-1 blocking mAbs, respectively. Blocking E-selectin and ICAM-1 on the monolayer significantly reduced PMN tethering to the EC (Fig. 3A) and subsequent melanoma cell adhesion efficiency (Fig. 3B), compared with the respective controls. Blocking ICAM-1 on WM9 significantly reduced melanoma adhesion efficiency compared with the control (Fig. 3B), which indicates PMN-melanoma binding via β2 integrins/ICAM-1 is important for PMN-facilitated melanoma cell arrest on the EC.

Figure 3.

Tethered PMN facilitates melanoma cell migration in close proximity to the endothelium under shear conditions. (A) PMN tethering frequency shows that the number of PMN that adhered to the endothelium per unit time and area is significantly reduced under the shear by blocking ICAM-1 or E-selectin on the monolayer (*P < 0.05 with respect to Control: PMN tethering on untreated monolayer). Shear stress was 2 dyn/cm2. (B) Melanoma cell adhesion efficiency shows that the number of WM9 cells arrested on the monolayer as a result of WM9-PMN collisions is significantly decreased by blocking either PMN-EC adhesion or WM9-PMN aggregation (*P < 0.05 compared with control samples; #P < 0.05 compared with the control). Shear stress was 2 dyn/cm2. (C) WM9 and C8161 adhesion efficiency at different shear rates (media viscosity 1.0 cP) over a period of 5 min. Antibody blocked cases (anti-LFA-1 and anti-Mac-1) are statistically significant (P < 0.05) compared with control at the same shear rate and cell type. (D) Relative contributions of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to binding of PMN-WM9 heterotypic aggregates on the monolayer. Blocking LFA-1 affects aggregation over the entire time course, whereas the effects of Mac-1 blocking are apparent only after 3 min. Data were normalized against the total number of tethered PMN on the monolayer at each time point. Error bars are mean ± S.E.M. for N ≥ 3.

Functional blocking mAbs against CD11a and CD11b were used to elucidate how PMN-melanoma aggregates were arrested on the endothelial monolayer under shear conditions. Blocking CD11a and CD11b, respectively, inhibited melanoma adhesion efficiency partially under all shear conditions tested. Results indicate that both LFA-1 and Mac-1 are required for melanoma cells to be maintained on the endothelium via melanoma-PMN aggregation, but may have different roles (Fig. 3C). Figure 3D shows that blocking CD11b did not significantly alter the rate of aggregation between entering melanoma cells and tethered PMN, and LFA-1 alone supported melanoma aggregation with tethered PMN on the EC initially. However, after an initial period of ~3 minutes, disaggregation of WM9-PMN aggregates on the monolayer surface proceeded more rapidly in the presence of anti-CD11b mAb than in the control (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that LFA-1 alone is necessary and sufficient for the initial formation of melanoma-PMN aggregates and Mac-1 maintains the stability of formed melanoma-PMN aggregates on the endothelial surface after the initial melanoma cell capture by PMN, which ultimately affects melanoma cell extravasation (Fig. 2C).

Therefore, we have found PMN increase melanoma cell arrest on the endothelium, which involves initial PMN tethering on the EC, subsequent PMN capture of melanoma cells and maintenance of their close proximity to the EC. LFA-1 influences the capture phase of PMN binding to both melanoma cells and the endothelium, while Mac-1 affects prolonged PMN-melanoma aggregation. Results also show that although PMN tethering on the EC is necessary for PMN-facilitated melanoma coming into and maintaining close contact with the EC, it is not sufficient.

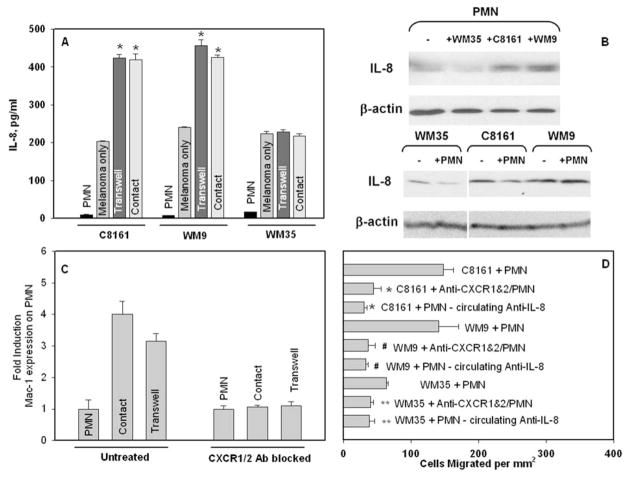

3.4 Melanoma Cell Increases IL-8 Production in PMN

ELISA and Western blot were used to assess chemotactic cytokine production by melanoma cells and PMN as a stimulus, which might be responsible for cell-cell signaling. Figure 4A shows that supernatant of PMN co-cultured with selected-type melanoma cells, either via Transwell (non-contact) or direct contact, contained different amounts of IL-8 production compared with summed background levels by PMN and melanoma cultured separately. There were significant increases in IL-8 from the supernatant of PMN co-cultured with highly-metastatic C8161 or WM9 cells compared with low-metastatic WM35 cells.

Figure 4.

PMN-facilitated melanoma cell arrest on the endothelium under flow conditions is modulated by endogenously produced IL-8. (A) ELISA detected increased secretion of IL-8 after PMN co-cultured with melanoma cells (C8161 and WM9, respectively), either in contact with each other or Transwell (not in contact but sharing the same medium). *P < 0.05 compared with the sum of IL-8 expression from PMN and melanoma only in the respective group. (B) Immunoblot results show that increased IL-8 is from PMN after their Transwell co-culture with respective melanoma cells. (C) Fold induction of Mac-1 expression on PMN after co-culture with C8161 and WM9 melanoma cells, respectively; either in contact or Transwell. Blocking the IL-8 receptors (CXCR1/2) resulted in no increase in Mac-1 expression compared with the control case. (D) Effects of IL-8 on PMN-facilitated melanoma migration. Isotype control cases were run for all the cases and were found to be statistically the same as the C8161+PMN case (*P < 0.04 with respect to C8161+PMN case; #P < 0.05 with respect to the WM9+PMN case; and **P < 0.05 with respect to WM35+PMN cases). All co-culture cases were performed in 4 hours, and all flow experiments were under a flow shear stress 0.4 dyn/cm2.

To more specifically identify which cells produced increased amounts of IL-8, cell lysates were then analyzed using immunoblot. Obviously, low-metastatic WM35 melanoma cells had less endogenous effect on PMN in increasing IL-8 production (Fig. 4B, top second lane). In comparison, PMN that had been Transwell co-cultured with highly-metastatic C8161 or WM9 cells (Fig. 4B, top third or fourth lane) contained significantly increased amount of intracellular IL-8 compared to PMN cultured alone without melanomas (Fig. 4B, top first lane). No melanoma cells from Transwell co-culture showed any detectable changes in intracellular IL-8 amount, with (+) or without (−) PMN (Fig. 4B, bottom).

Results suggest that PMN-melanoma communication creates a microenvironment that is potentially self-stimulatory, which causes changes in IL-8 production. We have found a trend of increasing amounts of IL-8 in PMN during co-culture versus nearly constant expression by the melanoma cells. Soluble IL-8 as released by melanoma cells and PMN would possibly have environmental effects of stimulating or immunoediting nearby PMN.

3.5 IL-8 Influences PMN Recruitment in Melanoma Cell

Untreated PMN or PMN treated with blocking antibodies for CXCR1 and CXCR2 were co-cultured with C8161 melanoma cells, either in contact (referred to as “Co-culture” case) or separated by a Transwell insert (referred to as “Transwell” case). Figure 4C indicates that non-CXCR1/2-blocked PMN co-cultured with melanoma cells experienced a nearly 4-fold increase in Mac-1 expression levels over those cultured alone for 4 hours. PMN with antibody blocked CXCR1 and CXCR2 showed no change in Mac-1 levels after co-cultured with C8161 cells compared with PMN cultured alone (Fig. 4C).

To elucidate the possibility that secreted chemokines could be a stimulus responsible for melanoma-PMN communication, the IL-8 receptors (CXCR1 and CXCR2) on PMN were antibody blocked and tested in the migration assay. Melanoma cell extravasations dramatically decreased under 0.4 dyn/cm2 shear stress in the presence of CXCR1/CXCR2-blocked PMN compared with unblocked PMN (~70% decrease with C8161; ~74% decrease in WM9; ~38% decrease in WM35) as shown in Figure 4D. Neutralizing anti-IL-8 antibody (1μg/ml) was also used to bind soluble IL-8 secreted by melanoma cells and PMN, which showed similar inhibitory effects on melanoma migration as those CXCR1/2-receptor blocked PMN cases (Fig. 4D).

Collectively, these results show PMN-facilitated melanoma cell arrest on the EC is modulated by endogenously produced IL-8. The influence of IL-8 in melanoma cell extravasation will be amplified under higher shear-rate conditions.

4 Discussion

The advancement of experimental assays to characterize cellular adhesion and migration are in a period of rapid development. For example, PMN-EC adhesion has been widely examined using various in vitro experimental systems. In vitro parallel-plate flow chambers are common assays for characterizing PMN-EC adhesion in shear flow (Lawrence et al., 1987). This type of flow chamber consists of a glass substrate, on which a monolayer of endothelial cells or a monolayer of transfected cells expressing endothelial adhesion molecules (Gopalan et al., 1997), or simply immobilized purified adhesion molecules (Lawrence and Springer, 1991; Cao et al., 1998; Lei et al., 1999) can be introduced to simulate an in vivo vascular wall. The strength of cell-substrate adhesion is determined by the shear stress needed to detach the cells from the surface. The limitation from this type of assay is that although the interactions between cells and vessel walls can be simulated, it is hard to study cell extravasation under flow conditions, even using phase-contrast videomicroscopy (Smith et al., 1989). For in vitro cell migration or invasion studies, Boyden-chemotaxis chambers are often employed, consisting of two wells separated by a micropore filter (Aznavoorian et al., 1990; Hodgson and Dong, 2001). Cells are placed in an upper well and allowed to migrate through the porous filter to the opposite side, in response to a chemoattractant source placed in the lower well. However, the limitation of this assay is that it is restricted to modeling only static conditions and does not permit investigating how dynamic flow conditions alter cell extravasation. None of these methods permits investigating how dynamic flow conditions alter cell extravasation. One motivation of this study is to apply a new approach to studying cell adhesion and extravasation using a novel in vitro flow-migration assay, which will allow us to investigate heterotypical cell-cell adhesion involved in melanoma cell extravasation under dynamic shear-flow conditions.

Significant progress has been made in the past decades toward understanding how PMN roll along the EC before forming shear-resistant bonds (Hentzen et al., 2000; Neelamegham et al., 1998). But, how do tumor cells bind the endothelium? One observation from in vivo videomicroscopy has indicated that tumor cells are trapped in capillaries and only arrested on the EC on the basis of vessel-size restriction in the microcirculation of whatever organ or tissue they extravasate (Chambers et al., 2000). It has been suggested that initial microvascular arrest of metastasizing tumor cells (from cell lines of 6 different histological origins) does not exhibit “leukocyte-like rolling” adhesive interaction with the EC (Thorlacius et al., 1997). In contrast, another in vivo study (Scherbarth and Orr, 1997) has discovered that the B16F1 melanoma cells could become arrested by shear flow-resisted adhesion to the walls of presinusoidal vessels in mice pre-treated with interleukin 1α (IL-1α). This suggests that release of cytokines into the bloodstream could bring arrest of melanoma cells in portal venules, by a chemoattraction and adhesion-mediated mechanism, rather than by size-restriction-only mechanism. Clearly, those studies are somewhat contradictory and additional work is needed to characterize the event in tumor cell adhesion to the EC. Several new studies have been launched recently in investigating whether PMN play any roles in tumor cell migration through the EC (Wu et al., 2001), especially under flow conditions (Jadhav et al., 2001; Slattery and Dong, 2003).

Hydrodynamic forces play an important role in regulating melanoma cell adhesion and extravasation in the microcirculation. Without an ability of selectin-or β2 integrin-mediated binding by melanoma cells alone to the endothelial surface under shear conditions, tumor cells may recruit PMN to aid in binding to the blood vessel wall. Results from Figure 2A show PMN influence melanoma cell extravasations under dynamic flow conditions, strongly correlated with tumor metastatic potentials. PMN-facilitated melanoma adhesion to the EC is a multi-step process. Blocking either ICAM-1 or E-selectin adhesion molecules on the endothelial monolayer reduces melanoma migration (Fig. 2B), which suggests PMN adhesion to the EC is necessary for melanoma cells arrest on the EC. Blocking the ICAM-1 molecules on C8161 cells also inhibits melanoma migration (Fig. 2B), which further indicates that a β2 integrins/ICAM-1 binding mechanism is involved in PMN-EC and melanoma-PMN adhesion. Down-regulation in LFA-1 or Mac-1 shows significant impact on the melanoma cell migration through the EC (Fig. 2C).

To understand whether changes in melanoma cell migration as shown in Figure 2 are due to melanoma-PMN adhesion or due to PMN-EC adhesion, the parallel-plate flow assay elucidates the distinct roles of PMN in melanoma cell interactions with the EC. Previous studies have shown that endothelial E-selectin initiates leukocyte capture to the EC and facilitates rolling by binding sialylated ligands expressed on PMN (Crutchfield et al., 2000; Kansas, 1996). Figure 3A shows blocking E-selectin and ICAM-1 on the EI monolayer inhibits the capture and rolling of PMN on the surface, resulting in decreased WM9 adhesion efficiency (Fig. 3B). Thus, PMN tethering to the EC is necessary for melanoma cell contact with the EC. Blocking ICAM-1 on WM9 cells significantly reduces the WM9 recruitment efficiency, indicating that a β2 integrins/ICAM-1 binding mechanism is involved in melanoma-PMN and PMN-EC interactions. Blocking either LFA-1 or Mac-1 function abrogates melanoma cell binding to tethered PMN under shear conditions (Fig. 3C). LFA-1 and Mac-1, the β2 integrins, have sequential roles in binding leukocytes to ICAM-1. Studies have shown that adhesion begins with LFA-1-dependant capture and is stabilized and maintained by Mac-1 (Neelamegham et al., 1998; Hentzen et al., 2000). Clearly from the results in adhesion assays (Fig. 3D), LFA-1 affects adhesion over the entire time course, whereas the effect of Mac-1 is only seen after 3 minutes. This difference is apparent because of the longer time necessary for migration to occur than adhesion. This suggests that the stabilized adhesion provided by Mac-1 to ICAM-1 is more of a factor in successful melanoma migration under shear, but Mac-1 and LFA-1 are both necessary and neither is sufficient to allow PMN to bind melanoma cells and the EC.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that melanoma cells produce soluble interleukin 8 (IL-8/CXCL8), which possesses PMN chemotactic and activating capacities (Smith et al., 1991; Yamamura et al., 1993) in addition to T-lymphocyte chemotactic activity (Larsen, 1989). PMN-melanoma cell attachment to the EC creates a microenvironment that is potentially self-stimulatory, which could alter PMN immuno-responses. Analysis of cytokine production by each of the two cell types during co-culture shows that melanoma-PMN communication induces changes in IL-8 expression. ELISA assays indicate that highly-metastatic melanoma cells alone produce relatively high amounts of IL-8 compared with low-metastatic cells; but in contrast PMN do not constitutively express high level IL-8 (Fig. 4A). IL-8 production increases significantly in supernatant of PMN co-cultured with melanoma cells, especially with highly metastatic cells. As determined by Western blot (Fig. 4B), endogenous IL-8 arises more significantly from PMN in response to highly-metastatic melanoma cells. There are no apparent changes in IL-8 secretion from various melanoma cells in the presence of PMN. A dramatic inhibition of Mac-1 expression on CXCR1/2-blocked PMN (Fig. 4C) suggests that melanoma-induced IL-8 from PMN could be responsible for the Mac-1 up-regulation on PMN. Significant inhibition in melanoma extravasation was found when neutralizing IL-8 antibody was present in the media, which clearly identifies the role of endogenously produced IL-8 in PMN-mediated melanoma cell extravasation (Fig. 4D).

Melanoma cells overly express GRO-α (growth-related oncogene-α; CXCL1) and GRO-γ (CXCL3), which promote PMN chemotaxis (Baggiolini et al., 1994) as well as melanoma growth both in vitro and in vivo (Balentien et al., 1991; Owen et al., 1997). CXCR2 is a major receptor for GRO, which was found in melanoma cells (Schadendorf et al., 1993). Because melanoma cells have not been found to express CXCR1 (Müller et al., 2001), a main receptor for IL-8, soluble IL-8 released by melanoma cells and PMN would probably have an environmental effect mainly on stimulating nearby endothelium or an autocrine effect on leukocytes. In addition to IL-8 and GRO receptors, Müller et al. (2001) detected significant levels of chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR7 in melanoma cells. The ligand for CXCR4 is SDF-1α (stromal cell-derived factor-1α; CXCL12), which is broadly expressed and has been demonstrated to arrest lymphocyte rolling on the EC under flow conditions (Campbell et al., 1998). Monocyte inflammatory protein (MIP-3β; CCL19), which is produced by activated PMN, is the ligand for CCR7 (Kasama et al., 1995). Recent study also shows that MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1) is expressed by melanoma cells, which could recruit PMN under chronic inflammatory conditions (Brent et al., 1999). These different chemokines and cytokines may initiate additional communication between melanoma cells and PMN. Such studies are currently being conducted in our laboratory.

Our studies present a novel finding that PMN-facilitated melanoma cell arrest on the EC within the circulation is modulated by endogenously produced IL-8. Therefore, understanding cancer immunoediting via intercellular communications between tumor cells and leukocytes will foster new approaches to cancer treatment through anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Scott Simon (UC Davis, CA) for providing EI cells; Dr. Meenhard Herlyn (Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA) for providing WM9 and WM35 cells; and Dr. Andrew Henderson (Penn State University, PA) for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant CA-97306, the National Science Foundation grant BES-0138474, the Health Research Formula Funding Program (SAP 41000-20604), and Johnson & Johnson – Innovative Technology Research Seed Grant. The authors appreciate the support of the Penn State General Clinical Research Center (GCRC), the staff that provided nursing care and helped perform the ELISA assays. The GCRC is supported by NIH Grant M01-RR-10732.

References

- Aznavoorian S, Stracke ML, Krutzsch HC, Schiffmann E, Liotta LA. Signal transduction for chemotaxis and haptotaxis by matrix molecules in tumor cells. J Cell Biology. 1990;110:1427–1438. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.4.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines – CXC and CC chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balentien E, Mufson BE, Shattuck RL, Derynck R, Richmond A. Effects of MGSA/GRO alpha on melanocyte transformation. Oncogene. 1991;6:1115–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent J, Alan RB, Makoto SU, Thosmas BI, Richard CW, Paul K. Chronic inflammation upregulated chemokines receptors and induces neutrophil migration to monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1269–1276. doi: 10.1172/JCI5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdick MM, McCarty OJT, Jadhav S, Konstantopoulos K. Cell-Cell Interactions in Inflammation and Cancer Metastasis. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2001;20:86–91. doi: 10.1109/51.932731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JJ, Hedrick J, Zlotnik A, Siani MA, Thompson DA, Butcher EC. Chemokine and the arrest of lymphocytes rolling under flow conditions. Science. 1998;279:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Donell B, Deaver DR, Lawrence MB, Dong C. In vitro side-view technique and analysis of human T-leukemic cell adhesion to ICAM-1 in shear flow. Microvasc Res. 1998;55:124–137. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1997.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers AF, MacDonald IC, Schmidt EE, Morris VL, Groom AC. Clinical targets for anti-metastasis therapy. Advances in Cancer Research. 2000;79:91–121. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(00)79003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissman JD, Hatfield J, Schaldenbrand M, Sloane BF, Honn KV. Arrest and extravasation of B16 amelanotic melanoma in murine lungs: a light and EM study. Lab Invest. 1985;53:470–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and Cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutchfield KL, Shinde PV, Campbell CJ, Parkos CA, Allport JR, Goetz DJ. CD11b/CD18-coated microspheres attached to E-selectin under flow. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:196–205. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Slattery MJ, Rank BM, You J. In vitro characterization and micromechanics of tumor cell chemotactic protrusion, locomotion, and extravasation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30:344–355. doi: 10.1114/1.1468889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn PG, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immuno-surveillance to tumor escape. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan PK, Smith CW, Lu H, Berg E, Mcintire LV, Simon SI. PMN CD18-dependent arrest on ICAM-1 in shear flow can be activated through L-selectin. J Immunol. 1997;158:367–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick MJ, Clayman GL. Chemokines in cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2001;2001:1–18. doi: 10.1017/S1462399401003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna N. The role of natural killer cells in the control of tumor growth and metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;780:213–226. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(85)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan JM, Liu DY. Adhesion: Its role in inflammatory disease. WH Freeman and Company; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hentzen ER, Neelamegham S, Kansas GS, Benanti JA, McIntire LV, Smith CW, Simon SI. Sequential binding of CD11a/CD18 and CD11b/CD18 defines newtuophil capture and stable adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Blood. 2000;95:911–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson L, Dong C. [Ca2+]i as a potential down-regulator of α2β1-integrin-mediated A2058 tumor cell migration to type IV collagen. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C106–C113. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WE, Lee J, Kuang WJ, Rice GC, Wood WI. Structure and functional expression of human interleukin-8 receptor. Science. 1991;253:1278–1280. doi: 10.1126/science.1840701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homey B, Müller A, Zlotnik A. Chemokines: Agents for the Immunotherapy of Cancer. Nature Rev Immunol. 2002;2:175–184. doi: 10.1038/nri748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav S, Bochner BS, Konstantopoulos K. Hydrodynamic shear regulates the kinetics and receptor specificity of polymorphonuclear leukocyte-colon carcinoma cell adhesive interactions. J Immunol. 2001;167:5986–5993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansas GS. Blood. Vol. 88. 1996. Selectins and their ligands: Current concepts and controversies; pp. 3259–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasama T, Strieter RM, Lukacs NW, Lincoln PM, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL. Interferon gamma modulates the expression of neutrophil-derived chemokines. J Investig Med. 1995;43:58–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key ME. Macrophages in cancer metastasis and their relevance to metastatic growth. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1983;2:75–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00046906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke ML. Ultraviolet radiation and immunology: something new under the sun: Presidential address. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6102–6105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen CG, Anderson AO, Appella E, Oppenheim JJ. The neutrophil-activating protein (NAP-1) is also chemotactic for T-lymphocytes. Science. 1989;243:1461–1466. doi: 10.1126/science.2648569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauffenburger D, Linderman JJ. Receptors: Models for binding, trafficking, and signaling. Oxford; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MB, McIntire LV, Eskin SG. Effect of flow on polymorphonuclear leukocyte/endothelial cell adhesion. Blood. 1987;70:1284–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MB, Springer TA. Leukocytes roll on a selectin at physiologic flow rates: Distinction from and prerequisite for adhesion through integrins. Cell. 1991;65:859–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90393-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei X, Lawrence MB, Dong C. Influence of cell deformation on leukocyte rolling adhesion in shear flow. J Biomech Eng. 1999;121:636–643. doi: 10.1115/1.2800866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K, Zakrzewicz A, Hanski C, Stoolman LM, Kansas GS. Sialylated O-Glycans and L-selectin sequentially mediate myeloid cell rolling in vivo. Blood. 1995;85:3727–3735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang SL, Slattery M, Dong C. Shear stress and shear rate differentially affect the multi-step process of leukocyte-facilitated melanoma adhesion. Experimental Cell Research. 2005;310:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta LA. Cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Scientific American. 1992;266:54–63. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0292-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta LA, Kohn EC. The microenvironment of the tumor-host interface. Nature. 2001;411:375–379. doi: 10.1038/35077241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A. Tumor-associated macrophages in neoplastic progression: a paradigm for the in vivo function of chemokines. Lab Invest. 1994;71:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough DB, McIntosh FA, Spanos C, Neelamegham S, Goldsmith HL, Simon SI. Cooperativity between selectins and β2-integrins define neutrophil capture and stable adhesion in shear flow. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;9:1179–1192. doi: 10.1114/b:abme.0000039352.11428.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miele ME, Bennett CF, Miller BE, Welch DR. Enhanced metastatic ability of TNF-treated maliganant melanoma cells is reduced by intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) antisense oligonucleotides. Exp Cell Res. 1994;214:231–241. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn LL, Melder RJ, Jain RK. Analysis of cell flux in the parallel plate flow chamber: implications for cell capture studies. Biophys J. 1994;67:889–895. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PM, Tiffany HL. Cloning of complementary DNA encoding a functional human interleukin-8 receptor. Science. 1991;253:1280–1283. doi: 10.1126/science.1891716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelamegham S, Taylor AD, Burns AR, Smith CW, Simon SI. Hydrodynamic shear shows distinct roles for LFA-1 and MAC-1 in neutrophil adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Blood. 1998;92:1626–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JD, Strieter R, Burdick M, Haghnegahdar H, Nanney L, Shattuck-Brandt R, Richmond A. Enhanced tumor-forming capacity for immortalized melanocytes expressing melanoma growth stimulatory activity/growth-regulated cytokine β and γ proteins. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:94–103. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<94::aid-ijc15>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nature Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker KD, Prabhakar V, Truskey GA. Effect of contact time and force on monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium. Biophys J. 2001;80:1722–1732. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou MN, Menter DG, Konstantopoulos K, Nicolson GL, McIntire LV. Integrin alpha4beta1/VCAM-1 pathway mediates primary adhesion of RAW117 lymphoma cells to hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells under flow. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:669–676. doi: 10.1023/a:1006747106885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadendorf D, Moller A, Algermissen B, Worm M, Sticherling M, Czarnetzki B. IL-8 produced by human malignant melanoma cells in vitro is an essential autocrine growth factor. J Immunol. 1993;151:2667–2675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadendorf D, Mohler T, Haefele J, Hunstein W, Kelholz U. Serum interleuckin-8 is elevated in patients with metastatic melanoma and correlates with tumor load. Melanoma Res. 1995;5:179–181. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherbarth S, Orr FW. Intravital video microscopic evidence for regulation of metastasis by the hepatic microvasculature: Effects of interleukin-1α on metastasis and the location of B16F1 melanoma cell arrest. Cancer Research. 1997;57:4105–4110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SI, Hu Y, Vestweber D, Smith CW. Neutrophil tethering on E-selectin activates β2 integrin binding to ICAM-1 through a mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J Immun. 2000;164:4348–435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Varney ML. Regulation of interleukin-8 expression in human malignant melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1532–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Varney ML, Bucana CD, Johansson SL. Expression of interleukin-8 in primary and metastatic malignant melanoma of the skin. Melanoma Res. 1999;9:383–387. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery M, Dong C. Neutrophils influence melanoma adhesion and migration under flow conditions. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:713–722. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery M, Liang S, Dong C. Distinct role of hydrodynamic shear in PMN-facilitated melanoma cell extravasation. Am J Physiol. 2005;288(4):C831–839. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00439.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CW, Marlin SD, Rothlein R, Toman C, Anderson DC. Cooperative Interactions of LFA-1 and Mac-1 with Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 in Facilitating Adherence and Transendothelial Migration of Human Neutrophils In Vitro. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1989;83:2008–2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI114111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WB, Gamble JR, Clark-Lewis I, Vadas MA. Interleukin-8 induces neutrophil transendothelial migration. Immunology. 1991;72:65–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: The multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey JR, Liggitt HD, Jones W, Hosick HL. Influence of migratory blood cells on the attachment of tumor cells to vascular endothelium. Int J Cancer. 1984;34:535–543. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910340417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorlacius H, Pricto J, Raud J, Gautam N, Patarroyuo M, Hedqvist P, Lindbom L. Tumor cell arrest in the microcirculation: Lack of evidence for a leukocyte-like rolling adhesive interaction with vascular endothelium in vivo. Clinl Immunology and Immunopathology. 1997;83:68–76. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Netten JP, Ashmead BJ, Parker RL, Thornton IG, Fletcher C, Cavers D, Coy P, Brigden ML. Macrophage-tumor cell association: a factor in metastasis of breast cancer? J Leukoc Biol. 1993;54:360–362. doi: 10.1002/jlb.54.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz A, Peveri P, Aschauer AO, Baggiolini M. Purification and amino acid sequencing of NAF, a novel neutrophil activating factor produced by monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;149:755–761. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch DR, Schissel DJ, Howrey RP, Aeed PA. Tumor-elicited polymorphonuclear cells, in contrast to “normal” circulating polymorphonuclear cells, stimulate invasive and metastatic potentials of rat mammary adnocardinoma cells. Proc Nat’l Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5859–5863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch DR, Bisi JE, Miller BE, Conaway D, Seftor EA, Yohem KH, Gilmore LB, Seftor REB, Nakajima M, Hendrix MJC. Characterization of a highly invasive and spontaneously metastatic human malignant melanoma cell line. Int J Cancer. 1991;47:227–237. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willimsky G, Blakenstein T. Sporadic immunogenic tumours avoid destruction by inducing T-cell tolerance. Nature. 2005;437:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature03954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu QD, Wang JH, Condron C, Bouchier-Hayer D, Redmond HP. Human neutrophils facilitate tumor cell transendothelial migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C814–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada KM. Introduction: Adhesion molecules in cancer. Part I Seminars in Cancer Biology. 1993;4:215–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura K, Kibbey MC, Kleinman HK. Melanoma cells selected for adhesion to laminin peptides have different malignant properties. Cancer Res. 1993;53:423–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetter BR. Adhesion molecules in tumor metastasis. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 1993;4:219–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]