Abstract

In planta analysis of protein function in a crop plant could lead to improvements in understanding protein structure/function relationships as well as selective agronomic or end product quality improvements. The requirements for successful in planta analysis are a high mutation rate, an efficient screening method, and a trait with high heritability. Two ideal targets for functional analysis are the Puroindoline a and Puroindoline b (Pina and Pinb, respectively) genes, which together compose the wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Ha locus that controls grain texture and many wheat end-use properties. Puroindolines (PINs) together impart soft texture, and mutations in either PIN result in hard seed texture. Studies of the PINs' mode of action are limited by low allelic variation. To create new Pin alleles and identify critical function-determining regions, Pin point mutations were created in planta via EMS treatment of a soft wheat. Grain hardness of 46 unique PIN missense alleles was then measured using segregating F2:F3 populations. The impact of individual missense alleles upon PIN function, as measured by grain hardness, ranged from neutral (74%) to intermediate to function abolishing. The percentage of function-abolishing mutations among mutations occurring in both PINA and PINB was higher for PINB, indicating that PINB is more critical to overall Ha function. This is contrary to expectations in that PINB is not as well conserved as PINA. All function-abolishing mutations resulted from structure-disrupting mutations or from missense mutations occurring near the Tryptophan-rich region. This study demonstrates the feasibility of in planta functional analysis of wheat proteins and that the Tryptophan-rich region is the most important region of both PINA and PINB.

NATURAL selection has captured a relatively small subset of potentially useful protein sequences. Unraveling the critical features of proteins via understanding the process of their evolution is a powerful approach for proteins present in many diverse species (Bashford et al. 1987; Hampsey et al. 1988). However, this approach is not feasible for the wheat puroindolines (PINs) that are present only in hexaploid wheat and related species (Massa and Morris 2006). The PINs are unique in structure in having a tryptophan-rich domain and are members of the protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein family (PF00234) (Finn et al. 2008).

The tryptophan-rich domain has been hypothesized to control PIN function (Giroux and Morris 1997), but there is no unbiased direct evidence for this since previous studies have focused on the tryptophan box alone (Evrard et al. 2008). A nonbiased approach would consist of random mutagenesis followed by functional analysis (Bowie et al. 1990). This approach has been used extensively for proteins that can be expressed in vitro using either random (Tarun et al. 1998; Guo et al. 2004; Smith and Raines 2006; Georgelis et al. 2007) or site-directed mutations (Miyahara et al. 2008; Osmani et al. 2008). However, functional analysis of many plant proteins in vitro may not be comparable to in planta analysis. In the case of puroindolines, there is no in vitro assay that properly mimics the synergistic binding of PINA and PINB to starch granules or is as easy to measure as grain hardness. Therefore, creation and analysis of a large number of new alleles in wheat in planta is an ideal approach to dissect PIN function.

The absence of high-throughput transformation and/or functional screening methods in most crop plants is the largest obstacle in the way of in planta protein functional analysis. However, high-throughput in vitro random or targeted mutagenesis followed by functional analysis has been demonstrated in Arabidopsis thaliana (Dunning et al. 2007) and Nicotiana benthamiana (Boter et al. 2007). Traditional in planta mutagenesis followed by analysis of loss-of-function mutations has been used to clone unknown genes (Xiong et al. 2001) or to define function for candidate genes (Haralampidis et al. 2001; Qi et al. 2006). A high-throughput in planta functional approach for PINA and PINB seems attractive for three reasons. First, the EMS mutation rate in wheat is higher than in any other plant (Slade et al. 2005; Feiz et al. 2009a). Second, PINs control the vast majority of variation in grain hardness (Campbell et al. 1999). Finally, a small-scale preliminary study indicated the feasibility of this approach (Feiz et al. 2009a).

PINA and PINB are cysteine-rich proteins unique in having a tryptophan-rich domain (Blochet et al. 1993) and together compose the wheat Hardness (Ha) locus (Giroux and Morris 1998; Wanjugi et al. 2007a). Ha is located on chromosome 5DS and is the major determinant of wheat endosperm texture (Mattern et al. 1973; Law et al. 1978; Campbell et al. 1999). Soft texture (Ha) results when both Pin genes are wild type (Pina-D1a, Pinb-D1a) while hard texture (ha) results from mutations in either Pin (Giroux and Morris 1997, 1998). Transgenic studies in rice (Krishnamurthy and Giroux 2001), wheat (Beecher et al. 2002; Martin et al. 2006), and corn (Zhang et al. 2009) have demonstrated that Pin mutations are causative to hard grain texture. PINA and PINB are not functionally interchangeable and control grain hardness via cooperative binding to starch granules (Hogg et al. 2004; Swan et al. 2006; Wanjugi et al. 2007a; Feiz et al. 2009b). PIN binding to starch granules is mediated by polar lipids (Greenblatt et al. 1995) and PIN abundance is correlated with seed polar lipid content (Feiz et al. 2009b). Variation in PIN function affects grain hardness along with nearly all end product quality traits (Hogg et al. 2005; Martin et al. 2007, 2008; Wanjugi et al. 2007b; Feiz et al. 2008). Determining PINs' function-determining regions could lead to greater knowledge of their mode of action and to wheat quality improvements. Current PIN functional analyses have been limited to in vitro tests of binding to each other (Ziemann et al. 2008) or to yeast membranes (Evrard et al. 2008).

Here, we report the creation and functional analysis in planta of new alleles of PINA and PINB. This is the first successful in planta functional analysis of a crop plant protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Creation and screening of an EMS-induced population:

A wheat EMS-induced M1 population was created using a protocol similar to that of Slade et al. (2005) with some modifications (Feiz et al. 2009a). Approximately 10,000 M0 seeds of the soft white spring cultivar Alpowa (PI 566596) were EMS mutagenized and grown as previously described (Feiz et al. 2009a) and a single head was harvested from the 3000 fertile M1 plants. The first group of 1000 M1:M2 heads was planted in May 2006 and seed was recovered from the 630 fertile M2 rows (Feiz et al. 2009a). The remaining 2000 M1:M2 head rows were planted in May 2007 at the Arthur H. Post Field Research farm near Bozeman, Montana with within-row plant spacing of 15 cm with 30 cm between rows and seed was harvested from the 1700 fertile M2 rows. Leaf tissue for DNA preparations was collected and pooled at the two- to three-leaf stage from at least 4 plants per row. The PCR amplification conditions, product purification, and direct sequencing protocol of Feiz et al. (2009a) were used in this study. The GAP4 and Pregap4 programs from Staden Package v1.6.0, 2004 (http://staden.sourceforge.net/staden_home.html) were used to analyze sequences. Sorting intolerant from tolerant (SIFT) (Ng and Henikoff 2003) was used to predict the tentative impact of mutations on protein function.

Creation of F2 populations:

Four M3 seeds from each Pin mutation line were planted in the greenhouse and used for direct sequencing of Pina and Pinb. Pin mutation-carrying plants were used as a pollen source in crosses to nonmutagenized Alpowa. One hundred F1:F2 seeds from each cross along with Alpowa parental seeds were planted in May 2008 at the Arthur H. Post Field Research farm near Bozeman, Montana with within-row plant spacing of 15 cm with 30 cm between rows. Leaves were collected from 48 individual F2 plants from each cross at the two- to three-leaf stage for genotyping.

Genotyping and phenotyping of F2 populations:

The primer pairs and PCR conditions of Feiz et al. (2009a) were used to genotype F2 plants growing in the field. Genotyping was completed via differential restriction digestion of Pina and Pinb mutant alleles (supporting information, Table S1) or via direct sequencing. F2:F3 seeds were harvested from single F2 plants homozygous for the presence (denoted as D1x in results) or absence (denoted as D1a) of a Pin mutation. Two composites of 150 F2:F3 seeds were prepared from each of the two homozygous Pin allele groups for each cross with each composite composed of 30 seeds from five random F2 plants from the plants grown in the field in 2008. Grain hardness and kernel weight were determined twice from samples of 50 seeds for each composite as well as Alpowa nonmutant seeds, using a single-kernel characterization system (SKCS) (Perten Instruments, Springfield, IL). The same planting, seed bulking, and SKCS analysis process was performed on F3:F4 seeds derived from the four F2:F3 mutant populations analyzed by Feiz et al. (2009a). The grain hardness and kernel weight means were used for analysis.

Analysis of variance was computed for grain hardness and kernel weight by including seed composite and genotype class combinations in the model using PROC GLM in SAS (SAS Institute 2004). The error represented genotype class combination by composite interaction. The impact of new alleles on grain characteristics was assessed by comparing the difference between mutant and wild-type class means for each population.

Expected EMS-induced mutation ratio calculations:

Observed mutation class ratios are presented as a simple proportion of total mutations. Expected mutation ratios were derived by calculating the proportion of all possible EMS-induced transition mutations within each codon and the subsequent possible amino acid changes.

RESULTS

Creation of novel Puroindoline alleles and segregating F2 populations:

To conduct in planta functional analysis of the Puroindolines we developed an EMS-mutagenized population using the soft white spring wheat Alpowa. Seventy-one Pina alleles were identified, of which there were 37 missense, 11 nonsense, and 23 silent mutations (Table 1). Of the 77 alleles of Pinb, we identified 31 missense, 12 nonsense, and 34 silent mutations. Pina and Pinb mutation density was calculated from the frequency of mutations identified via direct sequencing. We arrived at a mutation density of 1/11.5 kb and the frequencies of each mutation type were in close agreement with their predicted frequencies for Pina. But more silent and fewer missense mutations were observed than expected for Pinb.

TABLE 1.

Pin mutation frequency and density in Alpowa EMS-induced population

| Pina | Pinb | Both Pins | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation frequency via direct phenotyping and sequencinga | |||

| Missense | 37 | 31 | 68 |

| Nonsense | 11 | 12 | 23 |

| Silent | 23 | 34 | 57 |

| Total | 71 | 77 | 148 |

| Mutation frequency via sequencingb | |||

| Missense | 33 | 27 | 60 |

| Nonsense | 6 | 9 | 15 |

| Silent | 23 | 32 | 55 |

| Total | 62 | 68 | 130 |

| Mutation densityc | 1/12 kb | 1/11 kb | 1/11.5 kb |

| Observed mutation class ratios | |||

| Missense | 0.53 | 0.4 | 0.46 |

| Nonsense | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| Silent | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.42 |

| Expected mutation class ratiosd | |||

| Missense | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| Nonsense | 0.1 | 0.11 | 0.1 |

| Silent | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Chi-square P-valuee |

0.52 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

Total cumulative mutation frequency found via phenotyping of 630 and direct sequencing of 1700 M2 Alpowa lines.

The frequency of mutations found by direct sequencing of 1700 M2 Alpowa lines.

The mutation density was calculated using the frequency of mutations found via direct sequencing of 1700 M2 Alpowa lines.

Expected ratio of three types of mutations from total was calculated using all potential nucleotide substitutions expected from EMS-induced transition mutations (G to A or C to T).

P-values are from chi-square tests that were used to compare the number of observed and expected mutation types.

To test the effects of each unique missense Pin allele upon grain hardness, segregating F2 populations were developed by crossing 25 Pina and 21 Pinb missense-carrying M3 plants back to nonmutagenized Alpowa. Two identical Pinb, one silent Pina, two nonsense Pina, and two nonsense Pinb mutations were also crossed back to Alpowa as controls. Forty-six or 48 F2 plants per population were genotyped via restriction digestion of PCR-amplified Pina or Pinb or by direct sequencing, respectively. Ninety-four percent of the F2 populations showed 1:2:1 segregation ratios (Table S1). Three populations deviated from expectations in that the PINAV24I and PINBP41S populations contained more wild-type Pin allele plants and the PINBT67I population contained more mutant plants than expected.

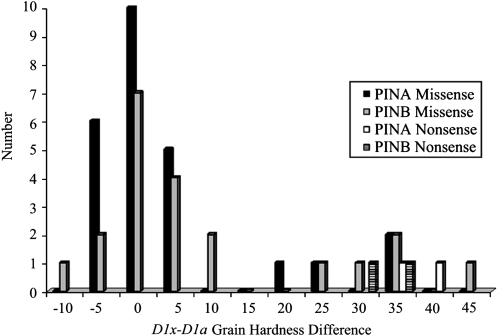

Mutations in the Puroindoline proteins cause changes in protein functionality as measured by grain texture:

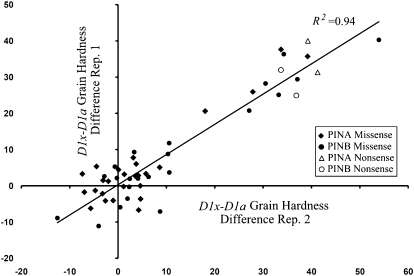

For each Pin missense allele tested, comparison groups consisted of F2:F3 lines homozygous positive or negative for the induced mutation. The net intrapopulation grain hardness difference between homozygote Pin mutant and wild-type groups was compared (Table S2 and Figure 1). Two nonsense and one silent mutation for each PIN were used as controls. The high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.94) demonstrated that the mutations control nearly all observed hardness variation. The two PINA nonsense mutations (W71Stop and Q93Stop) averaged a 37.8 grain hardness unit increase while the PINB nonsense mutations (Q20Stop and W116Stop) averaged a 31.8 hardness unit increase. The silent mutation in PINA (K60K) did not significantly change grain hardness nor were there significant differences between the duplicate PINB mutations. The vast majority of PINA and PINB mutations were less severe than the nonsense mutations in terms of increasing grain hardness. No mutations that affected grain hardness also affected seed weight.

Figure 1.—

The grain hardness difference between F2-derived Pin homozygous mutant (D1x) and wild-type (D1a) groups.

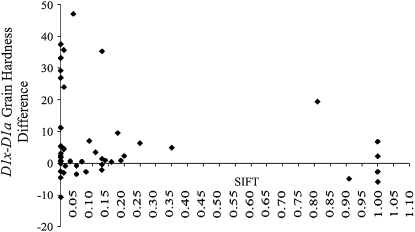

Direct measurement of missense mutation impacts vs. prediction by SIFT:

The SIFT program uses sequence homology in a protein family to predict the impact of missense mutations on protein function. SIFT predicted that 52% (13/25) of PINA and 52.4% (11/21) of PINB missense mutations would severely affect protein function (Table S1). The grain hardness differences between mutant and wild-type groups of 46 analyzed PIN mutant populations were plotted against their SIFT scores (Figure 2). Although SIFT was capable of predicting most severe mutations, it failed to correctly predict more than half of the missense mutations that did not affect grain hardness. This may indicate that some of the observed sequence conservation has no direct role in controlling grain texture. Further analysis focused on defining functional regions of PINA and PINB where missense mutations increased grain hardness.

Figure 2.—

The grain hardness difference between Pin homozygous mutant (D1x) and wild-type (D1a) groups vs. their individual SIFT scores. SIFT scores <0.05 are predicted to be deleterious (Ng and Henikoff 2003).

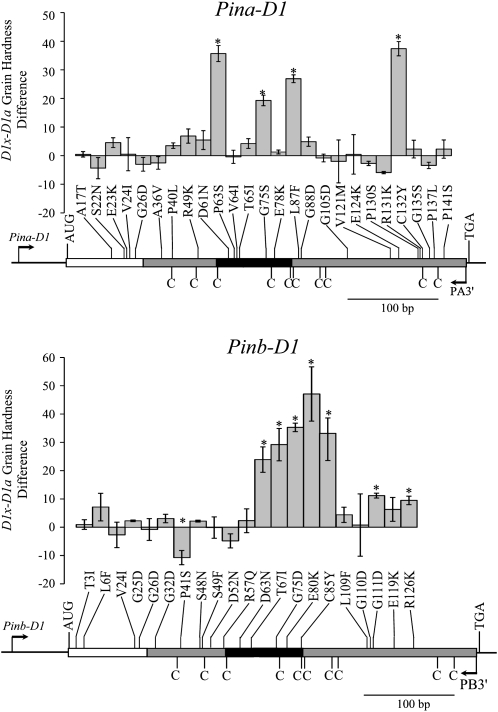

Functional analysis of new Puroindoline alleles demonstrates the importance of the tryptophan-rich region:

The tryptophan-rich domain of PINs is predicted to be in a coiled loop that joins the first two α-helices of PINs (Bihan et al. 1996). All severe (>20 hardness unit increase) PINA mutations were either in or in the vicinity of the Trp-rich loop (Figure 3). The only PINA severe mutation that occurred far from the Trp loop was a Cys-Tyr substitution (C132Y) while all severe PINB mutations were localized in the Trp-rich loop (Figure 3). One PINB mutation that reduced grain hardness (P41S) and two intermediate function mutations (G111D, R126K) were localized outside of the Trp-rich loop.

Figure 3.—

The mean grain hardness difference between lines homozygous positive or negative for individual PIN mutations relative to their location. Asterisks indicate where the hardness difference between an individual Pin mutant and its wild-type group was significant. The open boxed area denotes the signal peptide region while the shaded/solid boxed region denotes mature peptide sequence with the solid boxed region indicating the tryptophan-rich loop region. The positions of cysteines are denoted by C's. The position of the amplification primers is as shown.

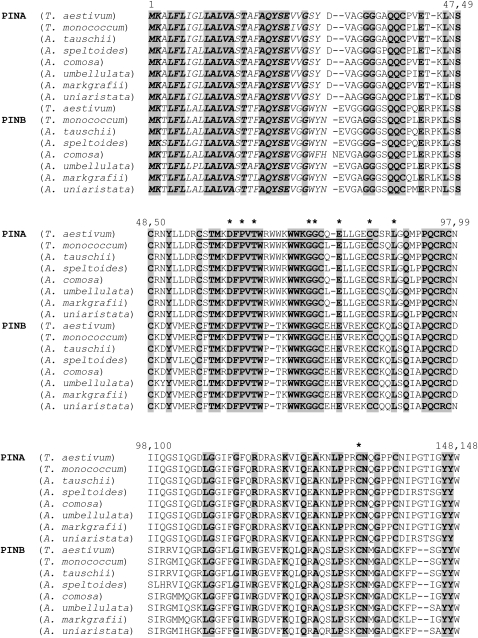

Functionally important residues are conserved between PINA and PINB:

PINA and PINB primary protein sequences from seven diploid wheat relatives were aligned (Table 2, Figure 4). Aligned separately, the PINA and PINB sequences showed a great degree of sequence conservation, with PINA being more highly conserved overall across species than PINB (data not shown). However, when aligned together, three main features are well conserved among all PINs (Figure 4). The first is the conservation of cysteines. These are presumably involved in intramolecular disulfide bridges. Second, the N-terminal region corresponding to the processing peptide is well conserved. The third well-conserved region is that surrounding the tryptophan-rich loop. Every one of the nine observed severe mutations occurred in amino acid residues that were absolutely conserved between PINA and PINB from all eight Triticeae species. Each of these severe mutations was either in cysteines or occurred in close proximity to the Trp-rich loop.

TABLE 2.

Plant material used to find the evolutionary conserved amino acids in PIN proteins

| GenBank accession no. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxona | Genome | Sourceb | Pina | Pinb |

| Triticum aestivum cultivar “Chinese Spring” | D | CItr 14108 | X69913 | X69912 |

| T. monococcum L. subsp. aegilopoides (Link) Thell. | Am | TA183 | DQ269819 | DQ269852 |

| Aegilops tauschii Coss. | D | TA1583 | AY252029 | AY251981 |

| Ae. speltoides Tausch var. speltoides | S | TA1793 | DQ269829 | DQ269862 |

| Ae. comosa Sm. in Sibth. and Sm.var. subventricosa Boiss. | M | TA2737 | DQ269846 | DQ269882 |

| Ae. umbellulata Zhuk. | U | TA1830 | DQ269847 | DQ269883 |

| Ae. markgrafii. | C | TA1906 | DQ269848 | DQ269884 |

|

Ae. uniaristata Vis. |

N |

TA2688 |

DQ269849 |

DQ269885 |

Taxa are listed by genome being represented and source.

Accession identifiers: CItr, National Small Grains Collection, Aberdeen, ID; TA, Wheat Genetics Resource Center, Kansas State University; X, AY, and DQ, National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank database.

Figure 4.—

Multispecies PINA and PINB protein alignment. Polypeptide primary sequences from representative diploid wheat relatives (see Table 2) were aligned using Clustal W (Thompson et al. 1994). Identical residues are shaded. Points of mutation that generate hardness differences >20 units from wild type are marked by an asterisk. For PINA these are P63S, G75S, L87F, and C132Y. For PINB these are D63N, T67I, G75D, E80K, and C85Y. The signal peptide is marked in italics. The tryptophan box loop region is underlined.

Functional classes of PINA and PINB mutants:

The majority of mutations had a minimal effect (±5 units) on PIN function as measured by grain hardness (Figure 5). Of the 12 mutations that had a large effect (>20 units) on hardness, 4 were nonsense mutations. All nonsense mutations increased hardness >30 units, showing that both PINs are required for full grain softness. The 8 remaining severe missense mutations were relatively equally distributed among PINA and PINB. Five identical missense mutations occurred in both PINA and PINB, with 2 occurring in the signal peptide and 3 in the Trp-rich region (Table 3). The two identical missense alleles found in the signal peptide did not alter grain hardness when occurring in either PIN. However, all three identical missense alleles within the Trp-rich domain of PINB increased grain hardness dramatically (18.5–45.2 units) while the function of PINA was unaffected.

Figure 5.—

Classification of F2 families by hardness difference between their homozygote mutant (D1x) and wild-type (D1a) groups.

TABLE 3.

The effect of missense mutations occurring in both PINA and PINB on grain hardness

| Region | Allele | Hardness change (D1x–D1a)a | Hardness change PINBx–PINAxb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal peptide | PINA V24I | 0.52 | −3.24 |

| PINB V24I | −2.72 | ||

| PINA G26D | −3.00 | 2.21 | |

| PINB G26D | −0.79 | ||

| Trp domain | PINA D61N | 5.46 | 18.48* |

| PINB D63N | 23.94 | ||

| PINA T65I | 0.61 | 28.56* | |

| PINB T67I | 29.17 | ||

| PINA E78K | 1.9 | 45.2* | |

| PINB E80K |

47.10 |

*Denotes significance in comparisons of the grain hardness change between the identical mutation in PINA and PINB at P < 0.05.

Difference in grain hardness in comparisons of two independently derived seed composites, where each seed composite was homozygous positive (D1x) or negative (D1a) for a Pin mutation.

Difference in impact of individual identical mutations between PINA and PINB upon grain hardness.

DISCUSSION

PINs are unique among plant proteins in having a tryptophan-rich hydrophobic domain. While they control grain hardness variation (Giroux and Morris 1998), which affects many wheat end-product quality traits (Campbell et al. 1999), their likely in vivo function relates to their antifungal properties. PINA and PINB are effective in vitro (Dubreil et al. 1998; Capparelli et al. 2005) and in vivo (Krishnamurthy et al. 2001) antimicrobial agents against bacterial and fungal pathogens.

To improve understanding of PIN function, we created an in planta source of EMS-induced Pina and Pinb mutations. Our observed mutation rate was 1 in 11.5 kb DNA (Table 1), twice that previously observed in hexaploid wheat (Slade et al. 2005). Crossing each PIN mutation line with the wild-type parent allowed us to perform functional analysis using F2 segregating lines. Most missense mutations were categorized into two groups on the basis of their grain hardness effects: a group with little impact on function and a group that retained little to no PIN function (Figure 3). Apart from mutations affecting cysteines, all other function-abolishing mutations were centered on the Trp-rich domain, indicating that this region is the most important for PIN function. Many PINA and PINB missense mutations naturally present in hard wheats are also centered on this domain (reviewed in Bhave and Morris 2008). Two such PINB missense alleles (PINBG75S and PINBW73R) were shown to negatively affect the degree to which PINB could penetrate lipid layers (Clifton et al. 2007a,b; 2008). This finding highlighted the key role of the Trp-rich loop in puroindoline–lipid interactions.

The probability that a missense mutation affects grain hardness was 0.16 for PINA and 0.38 for PINB. Using in vitro random mutagenesis, the average probability of nonfunctional missense mutations for a human DNA repair enzyme and a bacterial DNA polymerase was 0.34 (Guo et al. 2004; Loh et al. 2007), whereas it was 0.60 when estimated within the active sites of some human, bacteria, and viral proteins (Guo et al. 2004). The ratio of mutations destroying protein activity has been shown to decrease in proportion to the distance from the enzyme's active site (Bowie et al. 1990; Yano et al. 2008). Here, the inactivation probability within the Trp-rich loop was 0.50 for PINA and 1.00 for PINB. Further, there were three identical mutations within both PINA and PINB and all three PINB mutations destroyed function while those in PINA did not. To explain the significantly higher inactivation value of PINB relative to PINA, we hypothesize that the PINB grain texture-determining function is more vulnerable to missense changes than that of PINA.

Selective pressure may result in the evolution of proteins that are more tolerant of change and with lower inactivation probabilities than homologous proteins (Guo et al. 2004). In studies of Ha locus genes, Massa and Morris (2006) concluded that adaptive forces operated only at the Pina locus, resulting in strong positive selection at this locus consistent with its role as a plant defense gene. Consistent with the idea of PINA being more important in plants, Krishnamurthy et al. (2001) showed that PINA was more effective than PINB in controlling fungal diseases in transgenic rice. The results seen with disease control are consistent with several grain hardness studies. First, null mutations in PINA are more severe than null mutations in PINB (Table S2). Second, transgenic manipulation has demonstrated that while both PINA and PINB limit grain softness in soft wheats, PINB is a greater limiting factor than PINA (Swan et al. 2006). The results of this study are consistent with these observations and support the following conclusions: first, that both PINA and PINB must be functional for grain softness; second, the active site of each protein is the tryptophan-rich domain; third, PINB function is more critical to overall Ha locus function; and finally, this study demonstrates the feasibility of in vivo functional analysis of proteins in a crop plant.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service National Research Initiative Competitive Grants 2004-01141, 2007-35301-18135; by the Montana Board for Research and Commercialization Technology; and by the Montana Agricultural Experiment Station.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.106013/DC1.

References

- Bashford, D., C. Chothia and A. M. Lesk, 1987. Determinants of a protein fold. Unique features of the globin amino acid sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 196 199–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecher, B., A. Bettge, E. Smidansky and M. J. Giroux, 2002. Expression of wild-type pinB sequence in transgenic wheat complements a hard phenotype. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105 870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave, M., and C. F. Morris, 2008. Molecular genetics of puroindolines and related genes: allelic diversity in wheat and other grasses. Plant Mol. Biol. 66 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihan, T. L., J. E. Blochet, A. Désormeaux, D. Marion and M. Pézolet, 1996. Determination of the secondary structure and conformation of puroindolines by infrared and Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry 35 12712–12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blochet, J. E., C. Chevalier, E. Forest, E. Pebay-Peyroula, M. F. Gautier et al., 1993. Complete amino acid sequence of Puroindoline, a new basic and cystine-rich protein with a unique tryptophan-rich domain, isolated from wheat endosperm by Triton X-114 phase partitioning. FEBS Lett. 329 336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boter, M., B. Amigues, J. Peart, C. Breuer, Y. Kadota et al., 2007. Structural and functional analysis of SGT1 reveals that its interaction with HSP90 is required for the accumulation of Rx, an R protein involved in plant immunity. Plant Cell 19 3791–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, J. U., J. F. Reidhaar-Olson, W. A. Lim and R. T. Sauer, 1990. Deciphering the message in protein sequences: tolerance to amino acid substitutions. Science 247 1306–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K. G., C. J. Bergman, D. G. Gualberto, J. A. Anderson, M. J. Giroux et al., 1999. Quantitative trait loci associated with kernel traits in a soft hard wheat cross. Crop Sci. 39 1184–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Capparelli, R., M. G. Amoroso, D. Palumbo, M. Iannaccone, C. Faleri et al., 2005. Two plant puroindolines colocalize in wheat seed and in vitro synergistically fight against pathogens. Plant Mol. Biol. 58 857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, L. A., M. D. Lad, R. J. Green and R. A. Frazier, 2007. a Single amino acid substitutions in Puroindoline-b mutants influence lipid binding properties. Biochemistry 46 2260–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, L. A., R. J. Green and R. A. Frazier, 2007. b Puroindoline-b mutations control the lipid binding interactions in mixed Puroindoline-a:Puroindoline-b systems. Biochemistry 46 13929–13937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, L. A., R. J. Green, A. V. Hughes and R. A. Frazier, 2008. Interfacial structure of wild-type and mutant forms of Puroindoline-b bound to DPPG monolayers. Phys. Chem. 112 15907–15913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreil, L., T. Gaborit, B. Bouchet, D. J. Gallant, W. F. Broekaert et al., 1998. Spatial and temporal distribution of the major isoforms of puroindolines (puroindoline-a and puroindoline-b) and non specific lipid transfer protein (ns-LTP) of Triticum aestivum seeds. Relationships with their in vitro antifungal properties. Plant Sci. 138 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, F. M., W. Sun, K. L. Jansen, L. Helft and A. F. Bent, 2007. Identification and mutational analysis of Arabidopsis FLS2 leucine-rich repeat domain residues that contribute to flagellin perception. Plant Cell 19 3297–3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evrard, A., V. Lagarde, P. Joudrier and M. F. Gautier, 2008. Puroindoline-a and puroindoline-b interact with the Saccharomyces cerevisiae plasma membrane through different amino acids present in their tryptophan-rich domain. J. Cereal Sci. 48 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Feiz, L., J. M. Martin and M. J. Giroux, 2008. The relationship between wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grain hardness and wet-milling quality. Cereal Chem. 85 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Feiz, L., J. M. Martin and M. J. Giroux, 2009. a Creation and functional analysis of new Puroindoline alleles in Triticum aestivum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 118 247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiz, L., H. W. Wanjugi, C. W. Melnyk, I. Altosaar, J. M. Martin et al., 2009. b Puroindolines co-localize to the starch granule surface and increase seed bound polar lipid content. J. Cereal Sci. 50 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, R. D., J. Tate, J. Mistry, P. C. Coggill, J. S. Sammut et al., 2008. The pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 D281–D288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgelis, N., E. L. Braun, J. R. Shaw and L. C. Hannah, 2007. The two AGPase subunits evolve at different rates in angiosperms, yet they are equally sensitive to activity-altering amino acid changes when expressed in bacteria. Plant Cell 19 1458–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, M. J., and C. F. Morris, 1997. A glycine to serine change in Puroindoline b is associated with wheat grain hardness and low levels of starch-surface friabilin. Theor. Appl. Genet. 95 857–864. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, M. J., and C. F. Morris, 1998. Wheat grain hardness results from highly conserved mutations in the friabilin components Puroindoline a and b. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 6262–6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt, G. A., A. D. Bettge and C. F. Morris, 1995. The relationship among endosperm texture, friabilin occurrence, and bound polar lipids on wheat starch. Cereal Chem. 72 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H. H., J. Choe and L. A. Loeb, 2004. Protein tolerance to random amino acid change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 9205–9210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampsey, D. M., G. Dast and F. Sherman, 1988. Yeast iso-1-cytochrome c: genetic analysis of structural requirements. FEBS Lett. 231 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haralampidis, K., G. Bryan, X. Qi, K. Papadopoulou, S. Bakht et al., 2001. A new class of oxidosqualene cyclases directs synthesis of antimicrobial phytoprotectants in monocots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 13431–13436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, A. C., T. Sripo, B. Beecher, J. M. Martin and M. J. Giroux, 2004. Wheat Puroindolines interact to form friabilin and control wheat grain hardness. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108 1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, A. C., B. Beecher, J. M. Martin, F. Meyer, L. Talbert et al., 2005. Hard wheat milling and bread baking traits affected by the seed-specific overexpression of Puroindolines. Crop Sci. 45 871–878. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, K., and M. J. Giroux, 2001. Expression of wheat puroindoline genes in transgenic rice confers grain softness. Nat. Biotech. 19 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, K., C. Balconi, J. E. Sherwood and M. J. Giroux, 2001. Wheat puroindolines enhance fungal disease resistance in transgenic rice. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14 1255–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law, C. N., C. F. Young, J. W. S. Brown, J. W. Snape and J. W. Worland, 1978. The study of grain protein control in wheat using whole chromosome substitution lines, pp. 483–502 in Seed Protein Improvement by Nuclear Techniques. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna.

- Loh, E., J. Choe and L. A. Loeb, 2007. Highly tolerated amino acid substitutions increase the fidelity of Escherichia coli DNA Polymerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 282 12201–12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. M., F. D. Meyer, E. D. Smidansky, H. Wanjugi, A. E. Blechl et al., 2006. Complementation of the pina (null) allele with the wild type Pina sequence restores a soft phenotype in transgenic wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 113 1563–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. M., F. D. Meyer, C. F. Morris and M. J. Giroux, 2007. Pilot scale milling characteristics of transgenic isolines of a hard wheat overexpressing puroindolines. Crop Sci. 47 497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. M., J. D. Sherman, S. P. Lanning, L. E. Talbert and M. J. Giroux, 2008. Effect of variation in amylose content and puroindoline composition on bread quality in a hard spring wheat population. Cereal Chem. 85 266–269. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, A. N., and C. F. Morris, 2006. Molecular evolution of the puroindoline-a, puroindoline-b, and grain softness protein-1 genes in the tribe Triticeae. J. Mol. Evol. 63 526–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattern, P. J., R. Morris, J. W. Schmidt and V. A. Johnson, 1973. Location of genes for kernel properties in the wheat variety ‘Cheyenne’ using chromosome substitution lines. Proceedings of the 4th International Wheat Genetics Symposium, Columbia, MO, pp. 703–707.

- Miyahara, A., T. A. Hirani, M. Oakes, A. Kereszt, B. Kobe et al., 2008. Soybean nodule autoregulation receptor kinase phosphorylates two kinase associated protein phosphatases in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 283 25381–25391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, P. C., and S. Henikoff, 2003. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3812–3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmani, S. A., B. Bak, A. Imberty, C. E. Olsen and B. L. Møller, 2008. Catalytic key amino acids and UDP-Sugar donor specificity of a plant glucuronosyltransferase, UGT94B1: molecular modeling substantiated by site-specific mutagenesis and biochemical analyses. Plant Physiol. 148 1295–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X., S. Bakht, B. Qin, M. Leggett, A. Hemmings et al., 2006. A different function for a member of an ancient and highly conserved cytochrome P450 family: from essential sterols to plant defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 18848–18853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, 2004. SAS/STAT 91 User's Guide. SAS Institute, Cary, NC.

- Slade, A. J., S. I. Fuerstenberg, D. Loeffler, M. N. Steine and D. Facciotti, 2005. A reverse genetic, nontransgenic approach to wheat crop improvement by TILLING. Nat. Biotechnol. 23 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. D., and R. T. Raines, 2006. Genetic selection for critical residues in ribonucleases. J. Mol. Biol. 362 459–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan, C. G., F. D. Meyer, A. C. Hogg, J. M. Martin and M. J. Giroux, 2006. Puroindoline B limits binding of Puroindoline A to starch and grain softness. Crop Sci. 46 1656–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Tarun, A. S., J. S. Lee and A. Theologis, 1998. Random mutagenesis of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase: a key enzyme in ethylene biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 9796–9801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins and T. J. Gibson, 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanjugi, H. W., A. C. Hogg, J. M. Martin and M. J. Giroux, 2007. a The role of puroindoline A and B individually and in combination on grain hardness and starch association. Crop Sci. 47 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wanjugi, H. W., J. M. Martin and M. J. Giroux, 2007. b Influence of Puroindolines A and B individually and in combination on wheat milling and bread traits. Cereal Chem. 54 540–547. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, L., M. Ishitani, H. Lee and J. K. Zhu, 2001. The Arabidopsis LOS5/ABA3 locus encodes a molybdenum cofactor sulfurase and modulates cold stress– and osmotic stress–responsive gene expression. Plant Cell 13 2063–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano, T., E. Nobusawa, A. Nagy, S. Nakajima and K. Nakajima, 2008. Effects of single-point amino acid substitutions on the structure and function neuraminidase proteins in influenza A virus. Microbiol. Immunol. 52 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., J. M. Martin, B. Beecher, C. F. Morris, L. C. Hannah et al., 2009. Seed-specific expression of the wheat Puroindoline genes improves maize wet milling yields. Plant Biotechnol. 7 733–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann, M., A. Ramalingam and M. Bhave, 2008. Evidence of physical interactions of puroindoline proteins using the yeast two-hybrid system. Plant Sci. 175 307–311. [Google Scholar]