Abstract

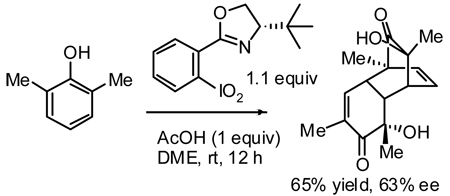

A new class of chiral iodine (V) derivatives has been prepared. These compounds have been found to transform ortho-alkylphenols into ortho-quinol Diels-Alder dimers with significant levels of asymmetric induction.

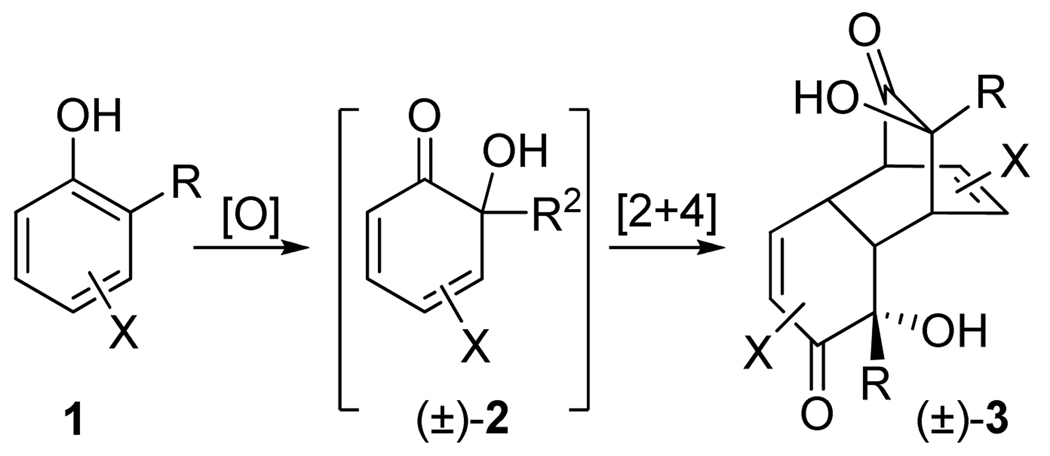

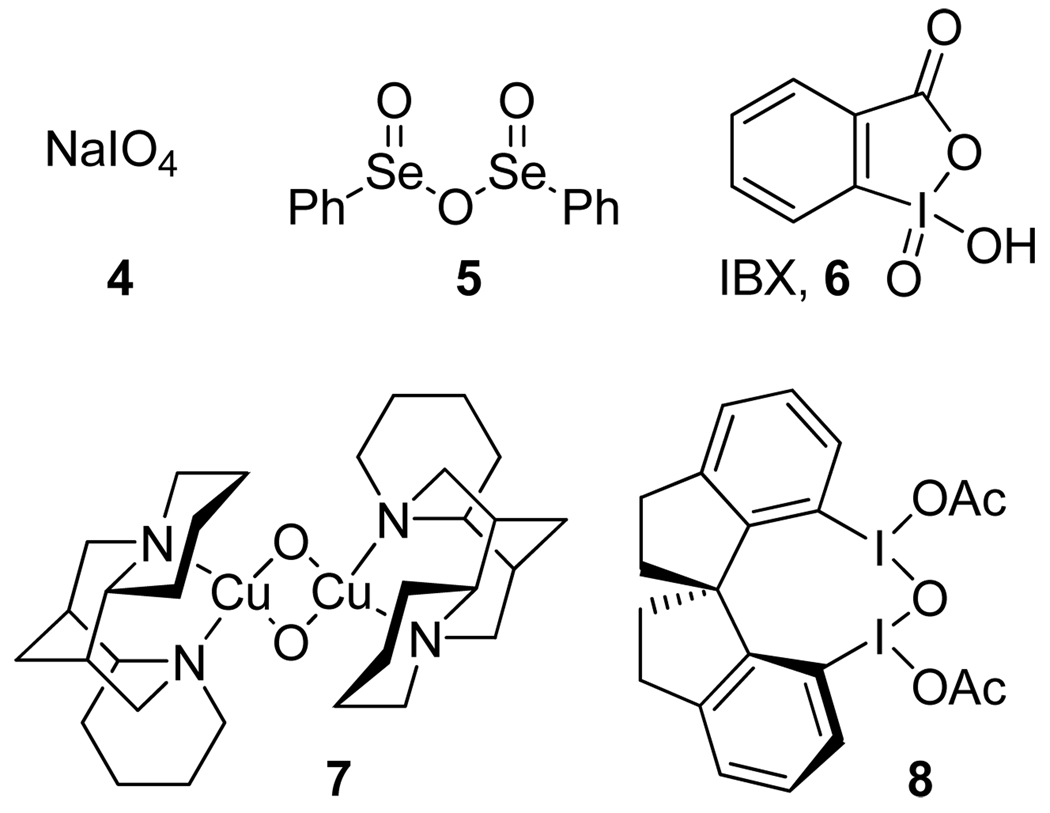

A reaction of o-alkylphenols 1 with achiral oxidants, such as sodium periodate 4,1 benzeneseleninic anhydride 52 and o-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX) 6,3 produces o-quinols 2, which dimerize spontaneously via a regio- and stereoselective intermolecular Diels-Alder reaction to give tricyclic products 3 (Scheme 1, Figure 1). The overall process is remarkable for the rapid increase in molecular complexity achieved in a single preparative step. Until a few years ago, enantioselective oxidative dearomatization of phenols remained unknown. In 2005, Porco et al. published a highly enantioselective oxidation of resorcinols with stoichiometric amounts of copper-spartein-dioxygen complex 7.4a In 2008, they extended this process to o-alkylphenols producing o-quinol dimers with 99% ee’s.4b The same year, Kita et al. developed a related process—asymmetric ortho-acetoxylation—using spirocyclic iodine (III) derivative 8.5 Prompted by these reports, we disclose the results of our recent studies in this area.

Scheme 1.

Transformation of o-alkylphenols into o-quinol dimers

Figure 1.

Reagents for oxidative dearomatization of o-alkylphenols

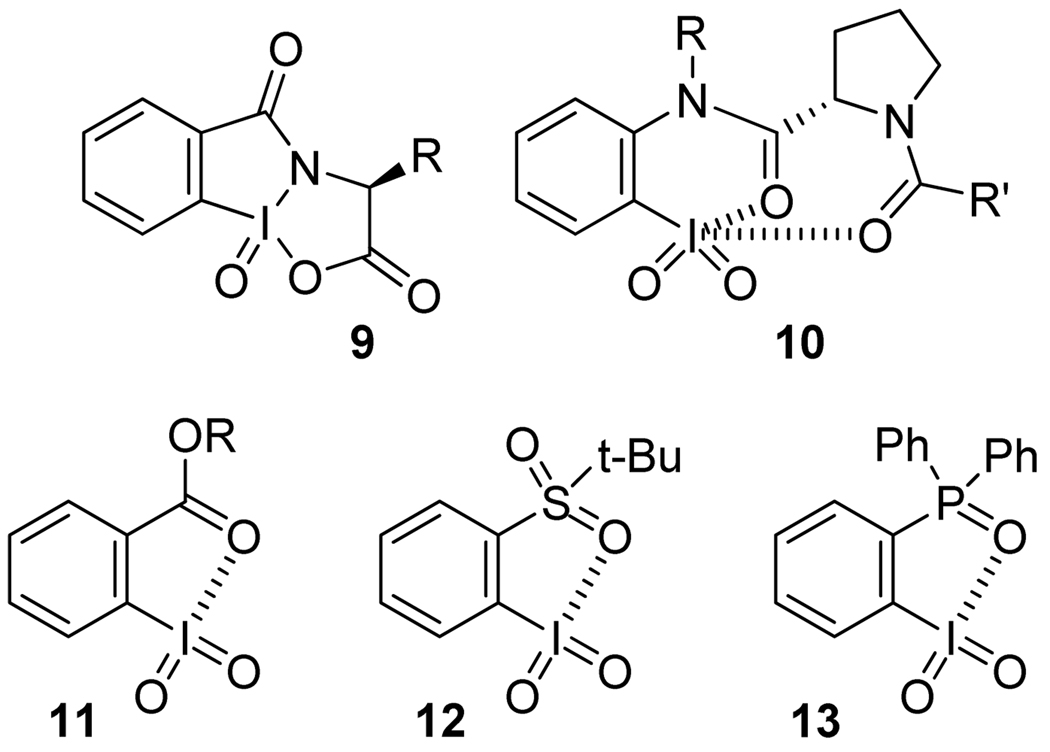

In connection with a total synthesis project, we sought to find new types of chiral oxidants capable of converting o-alkylphenols into o-quinol dimers in an enantioselective fashion. Inspired by the success of IBX in the racemic variant of this reaction,3 we decided to explore the potential of chiral organoiodine (V) compounds. Although ortho-substituted iodoxybenzene derivatives, such as IBX 66 and Dess-Martin periodinane,7 are widely used in organic synthesis,8 the utility of their chiral analogues remains relatively little explored. Chiral derivatives of IBX amide (9)9 and iodoxybenzene (10)10 (Figure 2) were synthesized and investigated by Zhdankin et al. The latter showed moderate levels of enantioselectivity in the oxidation of benzylic alcohols and thioanisole.

Figure 2.

o-Substituted iodoxybenzene derivatives

Iodoxybenzene derivatives ortho-substituted with a carbonyl, sulfonyl, or phosphonyl group, e.g., 10–13, are known to form pseudocyclic structures in which the iodine forms a captodative bond with the adjacent oxygen atom.11 Surprisingly, there have been no reports of the analogous iodoxybenzene derivatives with a neutral nitrogen ligand at the ortho-position. Given the ubiquitous use of oxazolines as chiral ligands for Lewis acids,12 we decided to investigate the preparation and properties of Chiral 2-(o-IodoxyPhenyl)-Oxazolines, abbreviated as CIPO’s (cf. 17, Scheme 2).

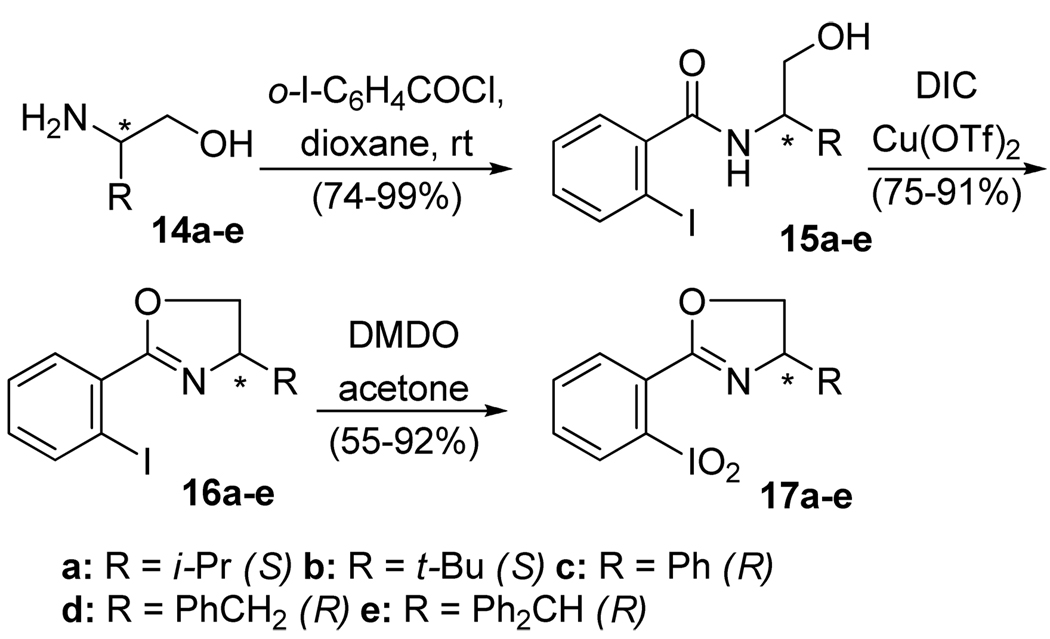

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of chiral 2-(o-iodoxyphenyl)-oxazolines

Several 2-(o-iodophenyl)-oxazolines 16a–e were prepared starting from chiral 2-amino alcohols 14a–e following known general protocols.13 Their oxidation with dimethyldioxirane11a,14 yielded the desired CIPO’s in moderate to good yields after chromatographic purification. The new compounds were obtained as white microcrystalline powders soluble in most organic solvents. The presence of the iodoxy group was evidenced by the diagnostic I=O stretches in IR (700–775 cm−1 region), and the chemical shifts of the ipso-carbon (149 ppm) and the ortho-proton (8.3 ppm) in NMR.11 All attempts to grow X-ray quality crystals of CIPO’s have so far proved unsuccessful. Thus, the existence of a captodative bond between the oxazoline nitrogen and the iodoxy group cannot be ascertained at this point.

To our delight, reaction of 0.6 equiv. of i-Pr-CIPO 17a with 1 equiv. of 2,6-dimethylphenol 1a in chloroform produced the desired o-quinol dimer 3a with an encouraging level of enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 1). Notably, Porco’s enantioselective oxidation method was reported to be unsuccessful in the case of this substrate.4b

Table 1.

Oxidation of 2,6-dimethylphenol 1a with CIPO’sa

| entry | oxidant | solvent | additve (equiv) |

% yieldb |

% ee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17a | CHCl3 | none | 29 | 30 |

| 2 | 17a | CHCl3 | AcOH (0.25) | 40 | 33 |

| 3 | 17a | CHCl3 | AcOH (1.0) | 47 | 36 |

| 4 | 17a | CHCl3 | AcOH (3.0) | 14 | 38 |

| 5 | 17a | CHCl3 | TFA (1.0) | dec | ND |

| 6 | 17a | PhMe | AcOH (1.0) | 43 | 53 |

| 7 | 17a | MeCN | AcOH (1.0) | 51 | 43 |

| 8 | 17a | CF3CH2OH | AcOH (1.0) | 58 | 17 |

| 9 | 17a | THF | AcOH (1.0) | 36 | 56 |

| 10 | 17a | DME | AcOH (1.0) | 51 | 55 |

| 11 | 17a | DME | none | 29 | 55 |

| 12 | 17a | DME | AcOH (0.25) | 43 | 56 |

| 13 | 17b | DME | AcOH (1.0) | 43 | 65 |

| 14 | 17c | DME | AcOH (1.0) | 36 | 46 |

| 15 | 17d | DME | AcOH (1.0) | 36 | 24 |

| 16 | 17e | DME | AcOH (1.0) | 36 | 32 |

| 17 | 17b | DME | AcOH (1.0) | 26(64)c | 62 |

| 18 | 17b | DME | AcOH (1.0) | 65d | 63 |

Conditions: 0.10 mmol 2,6-dimethylphenol 1a, 0.060 mmol CIPO 17a–e, 0.2 mL solvent, rt, 12 h, unless noted otherwise.

Yields are based on 1a, unless noted otherwise.

0.10 mmol 1a and 0.040 mmol 17b was used. The yield shown in parentheses is based on 17b.

0.10 mmol 1a and 0.11 mmol 17b was used.

However, the reaction stopped at low conversions. Mindful of Barton’s report on activation of the unsubstituted iodoxybenzene by trichloroacetic acid,15 we investigated the effect of acid promoters (entries 2–5). Stoichiometric amounts of acetic acid were found to improve the reaction rate, whereas trifluoroacetic acid led to decomposition. Several solvents were screened next (entries 6–10). DME (1,2-dimethoxyethane) proved to be optimal giving 3a in 51% yield and 55% ee (entry 10). Again, addition of acetic acid was confirmed to be beneficial in this solvent (entries 10–12). At this point, all other available CIPO’s were examined (entries 13–16). Only t-Bu-CIPO 17b displayed enhanced enantioselectivity compared to i-Pr-CIPO 17a and was therefore selected for further experimentation. The stoichiometry of the reaction with respect to the oxidant was initially uncertain, since in principle either one or both of the oxygen atoms of the iodoxy group could be utilized. An experiment with 2.5 equivalents of the substrate with respect to the oxidant confirmed that only one oxygen atom is utilized in the desired oxidation (entry 17). Accordingly, increasing the amount of the oxidant from 0.6 to 1.1 equivalents improved the yield of the dimer based on the substrate to 65% (entry 18). The rest of the starting material was mostly consumed by unidentified side reactions. The fate of the second oxygen atom of the iodoxy group remains unclear at this point. Only the fully reduced compounds, oxazoline 16b (54%) and amide 15b (19%) could be isolated after the reaction in entry 13.

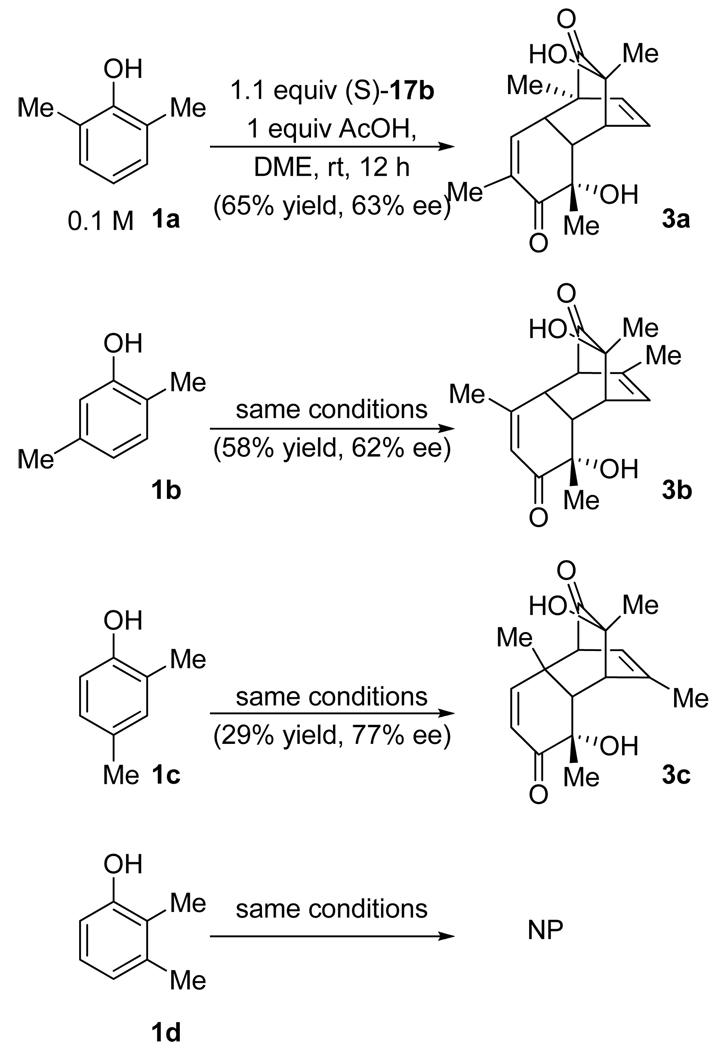

Application of the optimized set of conditions to other dimethylphenols was investigated next. 2,5-Isomer 1b produced the dimer (3b) with almost the same yield and enantioselectivity as 3a (Scheme 3). Oxidation of 2,4-dimethylphenol 1c attained 77% ee—the highest value observed in this study—albeit in a more modest yield. No dimer could be isolated from the reaction of 2,3-dimethylphenol 1d, which is consistent with previous reports.3c,4b The absolute configurations of 3b and 3c were deduced from their signs of optical rotation.4b The configuration of 3a was assigned by analogy.

Scheme 3.

Asymmetric oxidation of isomeric dimethylphenols with t-Bu-CIPO 17b

In conclusion, we have synthesized the first examples of iodoxybenzene derivatives with chiral oxazoline groups at the ortho-position and applied them to the enantioselective oxidation of phenols. Although the ee values remain moderate at this point, our results demonstrate the potential of the new class of chiral hypervalent iodine compounds in asymmetric synthesis. Further studies in this direction will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. V. V. Zhdankin and Dr. V. N. Nemykin (University of Minnesota-Duluth) for helpful discussions and suggestions. Financial support for this study was provided in part by NIGMS (R01 GM072682).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds. These materials are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Adler E, Holmberg K. Acta Chem. Scand. 1971;25:2775. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton DHR, Ley SV, Magnus PD, Rosenfeld MN. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1977;1:567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Magdziak D, Rodriguez AA, Van De Water RW, Pettus TRR. Org. Lett. 2002;4:285. doi: 10.1021/ol017068j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gagnepain J, Castet F, Quideau S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:1533. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lebrasseur N, Gagnepain J, Ozanne-Beaudenon A, Léger JM, Quideau S. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6280. doi: 10.1021/jo0708893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Zhu J, Grigoriadis NP, Lee JP, Porco JA., Jr J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9342. doi: 10.1021/ja052049g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dong S, Zhu J, Porco JA., Jr J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2738. doi: 10.1021/ja711018z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohi T, Maruyama A, Takenaga N, Senami K, Minamitsuji Y, Fujioka H, Caemmerer SB, Kita Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:3787. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frigerio M, Santagostino M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:8019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dess DB, Martin JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7287. [Google Scholar]

- 8.For recent reviews on hypervalent organoiodine compounds, seeWirth T, editor. Top. Curr. Chem. 2003;224:1–248.Zhdankin VV. Curr. Org. Synth. 2005;2:121.Ladziata U, Zhdankin VV. Arkivoc. 2006;9:26.Zhdankin VV, Stang PJ. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:5299. doi: 10.1021/cr800332c.

- 9.Zhdankin VV, Smart JT, Zhao P, Kiprof P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:5299. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladziata U, Carlson J, Zhdankin VV. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:6301. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Zhdankin VV, Koposov AY, Litvinov DN, Ferguson MJ, McDonald R, Luu T, Tykwinski RR. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:6484. doi: 10.1021/jo051010r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Macikenas D, Skrzypczak-Jankun E, Protasiewicz JD. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39:2007. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000602)39:11<2007::aid-anie2007>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Meprathu BV, Justik MW, Protasiewicz JD. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:5187. [Google Scholar]

- 12.For reviews, seeGomez M, Muller G, Rocamora M. Coord. Chem.Rev. 1999;193–195:769.Desimoni G, Faita G, Jørgensen KA. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3561. doi: 10.1021/cr0505324.

- 13.Crosignani S, Young AC, Linclau B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:9611. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray RW. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:1187. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton DHR, Godfrey CRA, Morzycki JW, Motherwell WB, Stobie A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:957. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.