Abstract

The role of emotion dysregulation in the intergenerational transmission of romantic relationship conflict was examined using multimethod and multiagent prospective longitudinal data across 21 years for 190 men and their mothers and fathers. As predicted, an individual’s emotion dysregulation was a key mediator in the transmission of relationship conflict, along with poor parenting skills. Parents’ emotion dysregulation was directly related to their son’s emotion dysregulation, which was in turn associated with the sons’ later relationship conflict. Additionally, parents’ emotion dysregulation was significantly related to their poor discipline skills, which were linked to the son’s emotion dysregulation and eventual relationship conflict. Findings highlight emotion dysregulation as a significant mechanism explaining the continuity of romantic relationship conflict across generations.

Interparental conflict is associated with negative emotional, behavioral, and social impacts for children (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000) with long-lasting consequences (Story, Karney, Lawrence, & Bradbury, 2004). There is extensive evidence that parental relationship conflict and/or divorce increases the likelihood that the next generation will experience distress in, or dissolution of, their own marriages (Kwong, Bartholomew, Henderson, & Trinke, 2003; Story et al., 2004). Undoubtedly, the transmission of marital conflict across generations is neither simple nor direct; a number of factors have been proposed as mediators of the intergenerational associations, including quality of parent-child relationships, poor parenting, and negative affect (Story et al., 2004). The predominant view is that by witnessing or experiencing parental conflict, children acquire ‘maladaptive interpersonal repertoires’ (Story et al., 2004) that generalize to other relationships outside the family of origin (Whitton et al., 2008). However, recent studies call into question whether such social learning processes alone adequately explain the intergenerational transmission of marital conflict and have called for the study of the developmental origins of such transmission (e.g., Harden et al., 2007; Whitton et al., 2008).

Emotion dysregulation has been implicated as both a predictor and an outcome of interparental conflict (e.g., Crockenberg, Leerkes, & Lekka, 2007; Maughan & Cicchetti, 2002; Schulz, Waldinger, Hauser, & Allen, 2005). In particular, according to the emotional security model of interparental conflict (Davies & Cummings, 1994), and the meta-emotion model (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1997), emotion dysregulation is critical for understanding the deleterious effects of interparental conflict. However, although researchers from the intergenerational family theory have long argued that relational patterns are reproduced across generations (e.g., Bowen, 1978; Harvey, Curry, & Bray, 1991), the extent to which emotion dysregulation influences the way romantic partners engage in conflict within and across generations remains to be addressed (Cupach & Olson, 2006). The primary purpose of the current study was to examine the potential contributions of emotional dysregulation to the intergenerational transmission of romantic relationship conflict using data spanning 2 decades from parents and sons who participated in the Oregon Youth Study (OYS). In the present study, we use the term relationship conflict to refer to a broad spectrum of conflict including disagreements and verbal arguments but not physical and psychological aggression, as research has shown that partner aggression has a different etiology (O’Leary, Slep, & O’Leary, 2007). Examining associations between emotion dysregulation and relationship conflict more generally will increase the generalizability of our findings.

Emotion Dysregulation and Interpersonal Relationships

The individual’s capacities to regulate emotion and emotion-related behaviors (e.g., anger) are key aspects of adaptive social functioning (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992). The lack of such regulation skills compromises the individual’s ability to properly engage with his/her environment (Cicchetti, Ganiban, & Barnett, 1991). Findings have consistently indicated that individuals with lower levels of regulatory skills tend to become overly aroused and display inappropriate emotional responses that are likely to cause significant difficulties in social interactions (Cicchetti, Ackerman, & Izard, 1995; Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992). Starting in early childhood, children with poor emotion regulation skills react more negatively and aggressively in social interactions than do their peers with better regulatory skills (e.g., Shultz et al., 2005). Although empirical findings on developmental continuities in emotion regulation skills are limited, emotion regulation patterns developed during early childhood are likely to continue throughout several developmental phases (Campbell, 1995). Children who have underdeveloped emotion regulation skills are more likely to continue to engage in conflictual and aggressive tactics in peer interactions in later childhood and adolescence (Calkins, Gill, Johnson, & Smith, 1999) and in adult relationships (Cupach & Olson, 2006). Thus, individuals who have demonstrated higher levels of emotion dysregulation in childhood and adolescence are likely to have difficulties in managing distress and conflict in interpersonal relationships in adulthood, particularly in romantic relationships. Such a conceptualization is also in line with the attachment literature which posits that the ability to regulate negative affect is one of the core tenets of the attachment system, which continues to influence emotional experiences in adult romantic relationships (e.g., Simpson, Collins, Tran, & Haydon, 2007).

Emotion Dysregulation in the Intergenerational Transmission of Romantic Relationship Conflict

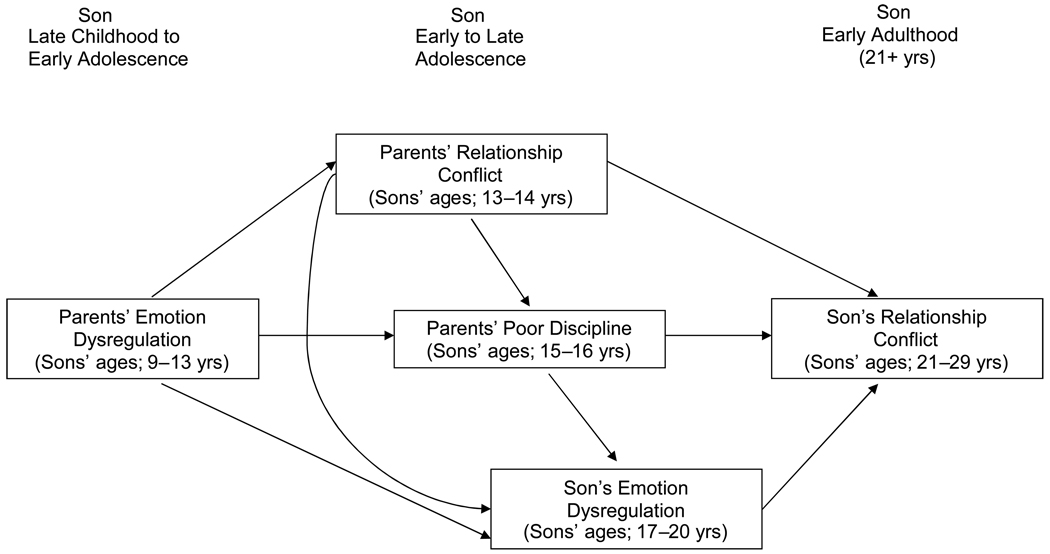

The studies mentioned above collectively indicate that emotion dysregulation might be a critical component in understanding relationship conflict across an individual’s lifespan. It also might be a critical mechanism in the transmission of relationship conflict across generations (e.g., Shultz et al., 2005). In the current study, we propose a model (Figure 1) to examine the role of emotion dysregulation in the intergenerational transmission of romantic relationship conflict. Given the importance of emotion dysregulation in interpersonal relationships, the model for the current study highlights the role of parents’ emotion dysregulation as one of the developmental origins of relationship conflict across generations. The model also posits three potential pathways through which parents’ emotion dysregulation may influence their son’s relationship conflict in adulthood.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model.

First, a potential direct link is posited between parents’ and sons’ emotion dysregulation patterns. Albeit limited, there is some evidence for such a link (e.g., Caspi, Bem, & Elder, 1989), suggesting that regulatory skills, in general, and emotional dysregulation, in particular, may be genetically transmitted to the next generation (e.g., Ganiban, Spotts, Lichtenstein, Khera, Reiss, & Neiderhiser, 2007). Such a direct link can also be explained by emotion contagion or spillover processes (Erel & Burman, 1995), thus serving as a mechanism by which romantic relationship conflict might be perpetuated across generations. As the current study design is not directly genetically informative, it would be difficult to disentangle genetic effects from other processes in such a direct link. However, if this path should prove to be significant, this would support to the idea that intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict is partially attributable to direct associations of emotion dysregulation across generations, in addition to those acquired through social interactions.

Parents’ emotion dysregulation may also influence offspring’s emotion dysregulation and relationship conflict indirectly through parental conflict. Interparental interactions serve as a salient social environment through which various aspects of emotion regulation, such as emotional expressiveness and management of emotional arousal are learned (Maughan & Cicchetti, 2002). Exposure to interparental conflict and the resulting emotionally charged environment may jeopardize the development of effective emotion processing and management abilities, increasing the risk for a generalized tendency toward emotion dysregulation (Davies & Cummings, 1994). The association of negative family-of-origin experiences with the development of children’s emotion systems and subsequent adaptation in childhood and adolescence has been well documented (Cummings et al., 2000; Maughan & Cicchetti, 2002; Murphy, Shepard, Eisenberg, & Fabes, 2004). For example, Kinsfogel and Grych (2004) found that interparental conflict was related to boys’ poor anger regulation, which was subsequently associated with the level of conflict in their own dating relationships. However, much of this research has not considered critical alternate pathways, in particular that emotion dysregulation in parents may be predictive of both their own relationship conflict and their poor discipline practices, and that it is the poor discipline practices rather than parental relationship conflict that partially mediate intergenerational associations in emotion dysregulation and relationship conflict.

There is evidence that parents’ emotion dysregulation may indirectly influence their offspring’s emotion dysregulation and relationship conflict through poor discipline skills. Research from the field of attachment suggests that from the very earliest interactions, caregivers help children to regulate emotion, first by physically soothing in infancy and later through negotiations about how to handle emotions in toddlerhood and preschool (Sroufe, 1996). Children continue to learn to modulate their emotional experiences and expressions through ongoing parent-child interactions in which parents provide guidance in understanding and coping with emotions (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Gottman et al., 1997). When parents use inconsistent (e.g., failure to follow through) and harsh (e.g., shouting and overly negative comments) discipline, the child’s development of effective emotion management strategies is likely to be hampered (Gottman et al., 1997). Parents who exhibit high levels of conflict in their relationships are particularly likely to show less consistent, less sensitive, and poorer discipline skills, compared with parents from happily married couples (e.g., Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Davies, Sturge-Apple, & Cummings, 2004; Fauchier & Margolin, 2004). Such ineffective, inconsistent parenting practices are likely to contribute to patterns of emotion dysregulation in their offspring which, in turn, could serve as a factor in the intergenerational transmission of romantic relationship conflict. Thus, poor discipline skills might serve as a link in an indirect path from interparental conflict to subsequent romantic relationship conflict in offspring.

Overview of the Study

Despite a growing interest in the developmental origins and processes of the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict, few attempts have been made to study emotion dysregulation in the context of intimate relationships in adulthood, particularly with nonclinical samples. The current study sought to explore the role of parents’ emotion dysregulation in interpersonal relationships, and its direct and indirect link to their children’s emotion dysregulation and romantic relationship conflict.

As indicated in Figure 1, we hypothesized that several different processes might explain the association between parents’ and offspring’s relationship adjustment, and the role of indirect effects through poor discipline were examined against the indirect effects through parental relationship conflict. We hypothesized that parents’ emotion dysregulation assessed when their sons were ages 9 to 13 would directly affect that of sons’ in adolescence. In addition, parents’ emotion dysregulation was predicted to be positively related to the parents’ own relationship conflict and poor (i.e., ineffective and inconsistent) discipline, and the latter would affect their sons’ relationship adjustment through the sons’ own emotion dysregulation.

For the purpose of the current study, emotion dysregulation is conceptualized in terms of mood lability, dysregulated negative affect, and situationally inappropriate affective displays (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). Note that emotion regulation is often conceptualized as encompassing two components: arousal (experiencing the emotion) and regulation (what is done with the emotion; Cole, Martin & Dennis, 2004). However, often both components are considered at once because they can be hard to measure separately (Cole et al., 2004). In this paper, both components were combined with a focus on the inability to regulate emotions. The measures of emotion dysregulation in the current study included symptoms of one's inability to regulate mood, affect, and emotion related behavior, including behavioral regulation and excessive expression of anger‥ ‥

Method

Participants

The current study was conducted using two prospective data sets: (1) the Oregon Youth Study (OYS), a community sample of youths who were at risk for the development of antisocial behavior and their parents; and (2) the OYS Couples Study, a later companion study of the youths and their intimate partners. The youths were originally recruited from fourth-grade classrooms of schools in areas with the highest rates of juvenile delinquency. All of the youths in all of the fourth-grade classrooms in the selected schools were eligible for participation in the study. Of 277 eligible families, 206 youths and their parents (74%) agreed to participate in the study. Ninety percent of the families were European American and they were predominantly from lower-class and working-class families (Hollingshead, 1975). Multimethod and multiagent assessments were conducted yearly, and retention rates were 94% or higher for the surviving youths during each of the study years (four young men died during the study period) in the past 2 decades. At the first assessment (Wave 1; W1), the average age of the youth was 10 years, and their mothers and fathers had a mean age of 33 years and 36 years, respectively. Single-parent families accounted for 35% of the sample (30% single mothers and 5% single fathers)1, whereas 65% were two-parent families (in 94%, the parents were married). The median family income was $10,000 to $14,999 per year (range = < $4,999 to > $40,000) at W1. Data for parents’ emotion dysregulation, interparental conflict, poor discipline, and their sons’ emotion dysregulation were taken from the OYS.

The Couples Study began when the youth were 17–18 years old in order to examine aspects of their romantic relationships. The youth and their intimate partners were assessed at six time points: ages 17–20 years (T1); ages 20–23 years (T2); ages 23–25 years (T3); ages 25–27 years (T4); ages 27–29 years (T5); and ages 29–31 years (T6). For the current study, the Couples Study T1 data were not included to avoid chronological overlap with measurement of predictor variables (i.e., youths’ emotion dysregulation). Couples Study T6 data were not included as the data were not ready for the present analysis. A total of 190 men (92% of the original OYS sample) participated in the Couples Study at least once across T2-T5. Sons’ relationship conflict data were taken from the first Couples Study assessment that the men participated in with their intimate partner. As the majority of the men participated at Couples Study T2 (n = 158), only 32 men’s data were taken from the subsequent waves. In order to take into account potential effects due to men’s differential ages at the time of the Couples assessment, age of the sons was controlled in the model. At the Couples Study time from which data were taken, 17% of the 206 young men were married, 37% were cohabiting, and 46% were dating2 and the young men had a median annual personal income of $17,000. Approximately 50% of the men had juvenile arrest records and only 52% graduated from high school with their class. Both the OYS and the Couples Study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Oregon Social Learning Center.

Measures

To maximize the advantage of the multiagent and multimethod approach, to avoid inflation of the Type I error rate secondary to multiple comparisons, and to ensure internal consistency and validity of scores, a composite score was computed for each construct with several indicators, on the basis of general construct-building guidelines that have been used with the OYS (Patterson & Bank, 1986). We first identified several variables a priori that were potential indicators of a given construct. Items within each scale had to show an acceptable level of internal consistency (an item-to-total correlation greater than .20 and α of .60 or higher) to be included. Then, each scale was examined for convergence with other scales designed to assess the same construct (i.e., the factor loading for a one-factor solution had to be .30 or higher, unless otherwise indicated). Once scales met these reliability criteria, they were combined to form a composite score. Observer ratings of fathers’ emotion regulation and one indicator for fathers’ conflict with partner were retained although the internal reliabilities of the measure was slightly lower than our criteria (both had a Chronbach’s α= .59) as the same items met the reliability criteria for mothers. When available, multiple waves of data were combined to increase the reliability of the data. Table 1 represents major constructs and indicators included in the study along with psychometric information.

Table 1.

Constructs Used in the Study

| Measure | OYS wave | Son’s age at assessment (years) | Respondent | # of items | Alpha or correlation | Sample item |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Emotional Dysregulation | 1–4 | 9–13 | Multiple | 2 | 0.50 | Mean of Mother and Father dysregulation. |

| Father Emotional Dysregulation | 1–4 | 9–13 | Multiple | 4 | 0.62 | |

| Father Emotional Dysregulation (W1) | 1 | 9–10 | Multiple | 2 | 0.21 | |

| Father Self Report | 1 | 9–10 | Self | 9 | 0.80 | Sometimes I shout, hit to let off steam. |

| Observer Report | 1 | 9–10 | Observer | 3 | 0.63 | Dad indicated anger. |

| Father Emotional Dysregulation (W2) | 2 | 10–11 | Self | 14 | 0.83 | I have restless periods where I can’t sit long in a chair. |

| Father Emotional Dysregulation (W3) | 3 | 11–12 | Multiple | 2 | 0.28 | |

| Child Report Phone Interview | 3 | 11–12 | Son | 1 | – | Was Dad angry or in bad mood the last 24 hrs? |

| Observer Report | 3 | 11–12 | Observer | 3 | 0.73 | Rate Dad angry to pleasant. |

| Father Emotional Dysregulation (W4) | 4 | 12–13 | Son | 1 | – | Was Dad angry or in bad mood the last 24 hrs? |

| Mother Emotional Dysregulation | 1–4 | 9–13 | Multiple | 4 | 0.67 | |

| Mother Emotional Dysregulation(W1) | 1 | 9–10 | Multiple | 2 | 0.26 | |

| Mother Self Report | 1 | 9–10 | Parents | 9 | 0.81 | I am a hotheaded person. |

| Observer Report | 1 | 9–10 | Observer | 3 | 0.59 | Mom indicated anger. |

| Mother Emotional Dysregulation(W2) | 2 | 10–11 | Parents | 14 | 0.90 | I get mad easily then get over it soon. |

| Mother Emotional Dysregulation(W3) | 3 | 11–12 | Multiple | 2 | 0.13 | |

| Child Report Phone Interview | 3 | 11–12 | Son | 1 | – | Was Mom angry or in bad mood the last 24 hrs? |

| Observer Report | 3 | 11–12 | Observer | 3 | 0.72 | Mom clearly indicated anger/irritability. |

| Mother Emotional Dysregulation(W4) | 4 | 12–13 | Son | 1 | – | Was Mom angry or in bad mood the last 24 hrs? |

| Parental Relationship Conflict | 5 | 13–14 | Multiple | 2 | 0.89 | Mean of Mother and Father scores. |

| Father Conflict with Partner | 5 | 13–14 | Multiple | 3 | 0.59 | |

| Interaction Task Coder ratings | 5 | 13–14 | Parents | 2 | 0.32 | Dad was verbally affectionate to spouse (reversed). |

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale(father) | 5 | 13–14 | Parents | 8 | 0.84 | How often do you and your partner quarrel? |

| Father Verbal Aggression | 5 | 13–14 | Multiple | 2 | 0.46 | |

| Father Report | 5 | 13–14 | Parents | 4 | 0.83 | Me to partner; Sulked and/or refused to talk about it. |

| Partner Report | 5 | 13–14 | Partner | 4 | 0.78 | Partner to me; Yelled and/or insulted. |

| Mother Conflict with Partner | 5 | 13–14 | Multiple | 3 | 0.68 | |

| Interaction Task Coder Ratings | 5 | 13–14 | Parents/Self | 2 | 0.31 | Mom was friendly to spouse (reversed). |

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale(father) | 5 | 13–14 | Parents | 8 | 0.85 | How often do you and your partner get on each other’s nerves? |

| Mother Verbal Aggression | 5 | 13–14 | Multiple | 2 | 0.50 | |

| Mother Report | 5 | 13–14 | Parents | 4 | 0.79 | Me to partner; Argued heatedly but short of yelling. |

| Partner Report | 5 | 13–14 | Partner | 4 | 0.79 | Partner to me; Stomped out of the room. |

| Parents’ Poor Discipline | 7 | 15–16 | Multiple | 2 | 0.72 | |

| Father′s Poor Discipline | 7 | 15–16 | Multiple | 2 | 0.53 | |

| Staff Ratings, Father Poor Discipline | 7 | 15–16 | Staff | 2 | 0.40 | |

| Interviewer Ratings | 7 | 15–16 | Interviewer | 1 | – | (This parent) seemed to discipline the child well (reversed). |

| Specific Affect Coder Impressions | 7 | 15–16 | Coder | 9 | 0.84 | Father seems to discipline child well (reversed). |

| Father Self-report Poor Discipline | 7 | 15–16 | Parents | 2 | 0.49 | |

| Poor Discipline Implementation | 7 | 15–16 | Parents | 6 | 0.70 | How often are you angry when you punish (child)? |

| Poor Discipline Results | 7 | 15–16 | Parents | 4 | 0.78 | How often when you discipline your son does he ignore it? |

| Mother′s Poor Discipline | 7 | 15–16 | Multiple | 2 | 0.50 | |

| Staff Ratings, Mother Poor Discipline | 7 | 15–16 | Staff | 2 | 0.38 | |

| Interviewer Ratings | 7 | 15–16 | Interviewer | 1 | – | (This parent) seemed to discipline the child well (reversed). |

| Specific Affect Coder Impressions | 7 | 15–16 | Coder | 9 | 0.85 | Seems to be a lack of mother discipline. |

| Mother Self-report Poor Discipline | 7 | 15–16 | Parents | 2 | 0.44 | |

| Poor Discipline Implementation | 7 | 15–16 | Parents | 6 | 0.64 | How often do you think that the kind of punishment you give your son depends on your mood? |

| Poor Discipline Results | 7 | 15–16 | Parents | 4 | 0.77 | How often do you have to discipline your son? |

| Son’s Emotional Dysregulation | 9–11 | 17–20 | Multiple | 3 | 0.74 | |

| Son’s Emotional Dysregulation (W9) | 9 | 17–18 | Multiple | 2 | 0.17 | |

| Self Report | 9 | 17–18 | Son | 11 | 0.83 | In the past 24 hrs, did you get in a fight? |

| Parent Report | 9 | 17–18 | Parents | 2 | 0.69 | |

| Mother Report | 9 | 17–18 | Mother | 14 | 0.80 | (Your child) is impulsive or acts without thinking. |

| Father Report | 9 | 17–18 | Father | 14 | 0.83 | (Your child) is stubborn, sullen, or irritable. |

| Son’s Emotional Dysregulation(W10) | 10 | 18–19 | Multiple | 2 | 0.20 | |

| Self Report | 10 | 18–19 | Son | 17 | 0.89 | I got in a fight in the last week. |

| Parent Report | 10 | 18–19 | Son/Parent | 1 | – | Your son seems depressed. |

| Son’s Emotional Dysregulation(W11) | 11 | 19–20 | Multiple | 2 | 0.30 | |

| Self Report | 11 | 19–20 | Son | 30 | 0.91 | I have a hot temper. |

| Parent Report | 11 | 19–20 | Son | 14 | 0.88 | My son repeats certain acts over and over. |

| Son’s Relationship Conflict | 12–20 | 20–29 | Parents | 3 | 0.68 | |

| Female Partner Report | 12–20 | 20–29 | Partner | 2 | 0.61 | |

| Conflict Tactics Scale | 12–20 | 20–29 | Partner | 4 | .83–.88 | Partner yelled at/insulted me. |

| Adjustment with Partner | 12–20 | 20–29 | Partner | 5 | .77–.85 | How often does your partner argue with you? |

| Son Conflict Tactics Scale | 12–20 | 20–29 | Self | 4 | .87–.91 | I argued heatedly, but short of yelling, with my partner. |

| Coder Ratings | 12–20 | 20–29 | Staff | 11 | .92–.95 | Male seemed unpleasant, mean, or cold to partner. |

Parental emotion dysregulation

Emotion dysregulation for mothers and fathers was assessed at OYS Waves 1, 2, 3 and 4, when their sons were 9–13 years old. As described above, we took advantage of the multimethod, multiagent approach; parents’ emotion dysregulation across different contexts was assessed via scales created from reports by parents, sons, and observers. Items were carefully chosen to capture the aspects of emotion dysregulation, including intense negative affect, and mood lability. The parents’ self-reports included scales from the Caprara Irritability Scale (Caprara et al., 1985), State-Trait Anxiety Scale (Spielberger et al., 1983), the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Hathaway & McKinley, 1951), and the Activity Survey (Jenkins, 1972). The observer report consisted of items from interviewer and coder ratings. The scale for the son’s reports on their parents’ emotion dysregulation was developed with items from a telephone interview asking about behaviors and experiences in the past day (Dishion et al., 1984), which was administered up to six times. For all of the individual scales, internal reliability values ranged from .59 to .90 across waves. The parents’ self-report, son’s reports, and observer reports were combined across waves for mothers and fathers separately (α (father) = .62; α (mother) = .67). Because emotion dysregulation scores for mothers and fathers were strongly associated (r = .50, p <.000), these were averaged to produce the parental emotion dysregulation composite score.

Parental relationship conflict

Relationship conflict for the fathers and mothers was the mean of three composites derived from instruments administered at OYS W5, when the sons were 13–14 years old. To differentiate effects of relationship conflict from those of intimate partner violence, items measuring physical or psychological aggression toward the partner were not included for the current study. The parents’ self report included items from the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976) and the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979) measuring dyadic verbal argument (e.g., “yelled at/or insulted”). The partner reports included the same items from the CTS that were included in the self-report. Observer reports included items from coder ratings of a home observation (OSLC, 1984). All of the individual scales from the DAS, CTS, and observer ratings exhibited good internal reliability (standardized α = .78 to .85). The three sets of scales from different reporters were combined for mothers and fathers, separately, (standardized α of .59 and .68, respectively). The father and mother composite scores were strongly associated (r = .89, p < .001), and were averaged for the parental relationship conflict score.

Parents’ poor discipline of sons in adolescence

Poor discipline of sons by parents was assessed at OYS Wave 7 (when sons were 15–16 years old) using observer and parent self-report scales. Two parent self-report scales from a structured in-person interview were used: a poor discipline implementation scale and a poor discipline results scale. These were combined within each parent to form an overall parent-report scale. The observer measure was developed with items from the parent interviewer ratings (OSLC, 1984–1987) and coder ratings of home observation (OSLC, 1984). Standardized alphas for parents’ self-report and observer ratings scales ranged from .64 to .85. The observer rating scale was combined with the parent self report for fathers (r = .53, p < .001) and mothers (r = .50, p < .001), separately. Mother and father scores were strongly associated (r = .72, p < .001) and, thus, were averaged to create the composite score for the parents’ poor discipline of their sons.

Sons’ emotion dysregulation

Emotion dysregulation in the young men was measured across Waves 9 (W9), 10 (W10), and 11 (W11) when they were 17 to 20 years old using self- and parent-reports. Items for the sons were similar to those for the parents, capturing the major aspects of emotion dysregulation. At W9, the OYS men’s self-report included scales from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, 1983), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), and the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck & Mermelstein, 1983). The parent report scales were developed from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). All of the individual scales from W9 showed good internal reliabilities and ranged from .80 to .83. Mother (α = .80) and father (α = .83) scales were strongly associated (r = .69, p < .001) and, thus, were averaged. Parent- and self-report scales were significantly associated (r = .17, p = .02) and, thus, were averaged to form the W9 composite for son’s emotion dysregulation. The W10 and W11 scales consisted of similar items, with a few exceptions. For instance, instead of the CBCL, items from the Young Adult Adjustment Scale (Capaldi, King & Wilson, 1992), the Young Adult Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1993a), and the Young Adult Self-Report (Achenbach, 1993b) were used as they were more developmentally appropriate. In addition, the parent scales at W10 and W11 were completed by the father or the mother rather than both parents (only the parent who had the most contact with the son participated in OYS after W9). The parent and son report scales were significantly associated at W10 and W11, r = .20 (p < .01) and r = .30 (p < .001), respectively. The overall emotion dysregulation composites from each of the three waves were averaged to form the son’s emotion dysregulation composite (α = .74).

Son’s relationship conflict

As is noted above, relationship conflict for the sons in adulthood was measured using data from the sons’ first assessments as participants in the Couples Study. As with the parents’ relationship conflict composite score, none of the items included indexed physical or psychological aggression toward the partner. The composite score for the sons included self- and partner-report scales using the same four items from the CTS as were used to assess parents’ relationship conflict, a partner-report scale from the Adjustment with Partner questionnaire (Kessler, 1990), and an observer report scale from ratings of a problem-solving session between the son and his partner. All items for each scale were identical across Couples Study assessment points. Standardized alphas for the scales ranged from .77 to .95. Both partners’ reports on the CTS were significantly associated (r = .61, p < .001) and, thus, were averaged. This scale was then combined with the partner and observer-report scales to produce the son’s relationship conflict variable (α = .68).

Data Analytic Strategies

Because of the relatively small sample size, observed variable path modeling was conducted using Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2008). To retain the maximum number of cases in the analyses and thus maximize statistical power, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used, which has been shown to provide unbiased estimates when data are missing at random (Arbuckle, 1996). Variables were examined for nonnormal distributions and outliers; all variables exhibited significant skewness and were transformed to more closely resemble a normal distribution. The significance of indirect effects was also tested using Mplus.

Results

Correlations

Table 2 shows correlations among the study variables. Parents’ emotion dysregulation was significantly and positively associated with their reports of relationship conflict, their use of poor discipline, and the sons’ emotion dysregulation in late adolescence. Parents’ relationship conflict was positively related to their poor discipline skills. Parents’ poor discipline was significantly and positively associated with the sons’ emotion dysregulation as well as with the sons’ relationship conflict in young adulthood. As expected, the sons’ emotion dysregulation during late adolescence was positively related to their relationship conflict in young adulthood. Age at the time of the son’s first Couples participation was significantly and negatively associated with his relationship conflict.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Study Variables (N = 190)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parental dysregulation | |||||

| 2. Parental relationship conflict | .17* | ||||

| 3. Parental poor discipline skill | .42*** | .37*** | |||

| 4. Son’s dysregulation | .34*** | .07 | .27*** | ||

| 5. Son’s relationship conflict | .10 | .04 | .20** | .32*** | |

| 6. Son’s age | .02 | −.04 | −.02 | −.06 | −.21** |

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Proposed Model

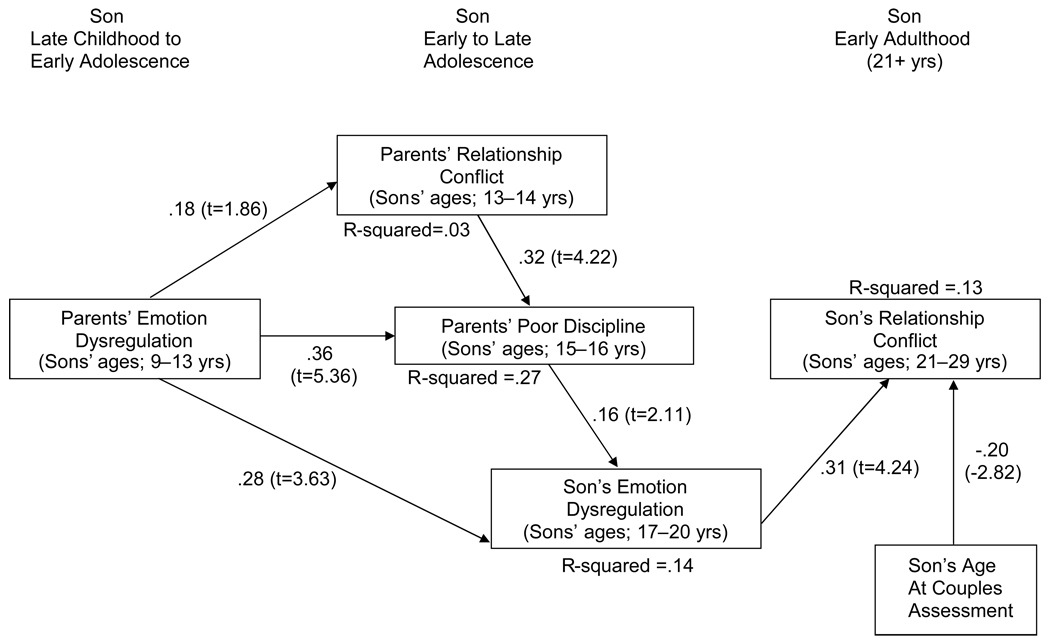

The full model depicted in Figure 1 was tested first with the son’s age added to control for its effects on his relationship conflict; then nonsignificant paths were trimmed. The trimming did not significantly diminish the model fit, nor did it influence the significance of the paths that were included in the final model. Therefore, the trimmed model was selected as most parsimonious (Figure 2). The model fit the data very well (χ2 [8] =6.17, p= .63, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.04, RMSEA = .000). As hypothesized, there was a direct link from parents’ emotion dysregulation to sons’ emotion dysregulation, which was, in turn, related to sons’ relationship conflict with their partners. Parents’ emotion dysregulation was only marginally significant in predicting their own relationship conflict. As predicted, parents’ emotion dysregulation was significantly and positively related to their poor discipline skills directly, though not indirectly through their relationship conflict. Parents’ poor discipline was positively related to their son’s emotion dysregulation, which, in turn, predicted his relationship conflict. Parents’ relationship conflict did not have significant direct effects on their son’s emotion dysregulation or his later relationship conflict.

Figure 2.

Trimmed model with structural parameter estimates.

Following recommendations from Preacher and Hayes (2008), we conducted significance tests on the indirect or mediating effects using bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993). The results indicated that parents’ emotion dysregulation influenced sons’ relationship conflict through the sons’ emotion dysregulation (.084 CI [.029, .139]). Parents’ emotional regulation also significantly affected sons’ emotional dysregulation through the parent’s use of poor discipline (.057, CI [.001, 112]). However, based on 95% confidence intervals, there were no other significant indirect effects.

Discussion

The current study used multimethod, multiagent prospective longitudinal data to examine the role of emotion dysregulation in the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict. As predicted and despite the long interval across the study years (approximately 2 decades), a significant association between parents’ and sons’ emotion dysregulation was evidenced. As hypothesized, sons’ emotion dysregulation was subsequently related to their own relationship conflict. Additionally, the paths leading to sons’ relationship conflict were more likely to involve their parents’ emotion dysregulation and poor discipline than parents’ relationship conflict. This supports the argument that the individual’s ability to regulate emotion and emotion-related behaviors (e.g., anger, hostility) plays a significant role in the cross-generational associations of relationship conflict as proposed in the model (Figure 1).

This finding is consistent with studies showing that poor emotion regulation skills may underlie a range of problematic behaviors, including delinquency (e.g., Giancola, 1995), substance abuse (Finn, Sharkansky, Brandt, & Turcotte, 2000; Martin, Lynch, Pollock, & Clark, 2000), and maladjustment in social relationships (e.g., Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992; Shultz et al., 2005). The current study adds to the literature by demonstrating that emotion dysregulation seems to be a major underlying mechanism shaping romantic relationships within generations. Individuals with poor emotion regulation skills are less likely to modulate and inhibit negative emotions and related behaviors and, thus, may display more inappropriate strategies when interacting with romantic partners. Furthermore, the findings also add to a growing number of studies suggesting that emotion regulation abilities play an important role in the transmission of behaviors across generations. A recent study examining the intergenerational transmission of substance use across three generations in the OYS sample showed that poor inhibitory control (a self-regulatory ability) was a key risk factor in the intergenerational transmission of both illicit drug use and poor discipline practices (Pears, Capaldi & Owen, 2007). The current study demonstrates that poor self-regulatory abilities play a crucial role in the transmission of romantic relationship conflict as well.

There was a significant direct association between parents’ and sons’ emotion dysregulation. This direct link may be due to a number of possible routes of transmission. First, it is in line with recent findings suggesting that deficits in emotion regulation abilities may be determined by areas of the brain subject to significant genetic influence (Beaver, Wright, & Delisi, 2007; Cauffman, Steinberg, & Piquero, 2005). The determination of such genetic linkage was beyond the scope of the current study. However, if parents’ tendencies toward emotion dysregulation were passed on to the next generation through common genetic risk factors, the developmental origins of conflictual interactions in romantic relationships might thus involve emotional or temperamental risk related to biological risk. Alternatively, this direct link may also reflect emotion contagion or spillover processes (Erel & Burman, 1995). To our knowledge, this study is the first long-term, prospective study to show that continuity in emotion dysregulation from parents to sons explains significant variation in the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict. As such, further replication is warranted.

As hypothesized, parents’ emotion dysregulation seems to influence their sons’ emotion dysregulation partially through poor discipline skills. Thus, parents’ poor emotion regulation skills significantly undermine parenting, which then disrupts the development of emotion regulation in offspring. This is consistent with previous findings suggesting that parents’ intrapersonal characteristics (e.g., meta-emotion structures) affect their parenting, which in turn influences the child’s adjustment (Embry & Dawson, 2002; Gottman et al., 1997). The mediating effects of poor discipline indicate that emotion dysregulation may be passed onto the next generation through several mechanisms, including both direct and indirect social processes. To fully understand the intergenerational links in relationship conflict, future research needs to consider these multiple processes.

The finding that relationship conflict in one generation did not directly predict relationship conflict in the next lends support to the hypothesis that intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict may not occur through direct learning (Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Conger, Cui, Bryant, & Elder, 2000). Relationship discord was not significantly associated with offspring’s emotion dysregulation according to bivariate correlational analysis. It is not clear why the indirect pathways from parents’ emotion dysregulation to sons’ relationship conflict through parents’ relationship conflict were not significant. It could be the case that the effects of parents’ relationship conflict on that of their sons were weak because the variable representing parents’ relationship conflict was taken from a single assessment point and, thus, somewhat more limited than other variables in the model. The significance of interparental conflict in the transmission of relationship conflict requires further exploration.

In general, our findings suggest that parent and offspring emotion dysregulation might be one of the major developmental pathways through which interparental conflict is transmitted from one generation to the next as implied in previous research on meta-emotion structure and offspring and family conflict and violence (Gottman et al., 1997). One clinical implication for marital intervention and parenting programs is that they should target not only specific behavioral patterns or skills but also personality characteristics in order to reduce relationship conflict and poor discipline behavior. In other words, programs that focus on learning specific strategies for managing issues pertaining to couples’ relationships may not be sufficient to modulate emotions that arise during other interactions (e.g., with children). If combined with problem-solving skills, components that facilitate emotional regulation and competence by increasing awareness of one’s own and others’ emotions, as well as the ability to regulate negative emotion will benefit families. Such efforts could ultimately reduce the transmission of relationship conflict to future generations.

Although the current study used multimethod, multiagent prospective data across two generations, a few limitations should be noted. First, when initially recruited, 30% of the families were headed by single mothers and thus there was no data on fathers. To reflect the ecology of the family, as well as to maximize sample size and instrument reliability, the current study combined mother and father data because mother and father reports were significantly related. However, it is possible that pathways could differ for mother-son and father-son dyads. This question has been a topic of a number of past studies. Although some have found that father-child relationships, compared with mother-child relationships, are more sensitive to the effects of marital conflict (Margolin, Christensen, & John, 1996), others have failed to find significant differences (Erel & Burman, 1995). Future studies should examine the contributions of maternal and paternal emotional dysregulation, relationship conflict, and discipline skills on intergenerational transmission separately. Also, no data were available on the sons’ partners’ emotion dysregulation; thus, the possible contribution of those partners to relationship conflict was not modeled in the current study. It is possible that intergenerational transmission may be moderated by partner characteristics. Recent findings from a three-generational study using this sample suggests that the sons’ use of poor and harsh discipline was predicted not only by the discipline practices of his parents but also by his partner’s characteristics and discipline practices (Capaldi, Pears, Kerr, & Owen, 2008). Future studies should examine the potential contribution of men’s partners in the intergenerational transmission of relationship conflict. In addition, before findings from the present study may be generalized to other populations, the dimensions of emotion dysregulation and the measures assessing this construct need to be further investigated. Finally, although the OYS men and their families were originally recruited through randomly selected schools in neighborhoods with higher rates of delinquency, the at-risk characteristics of the sample may limit the generalizability of the findings.

Despite these limitations, this study used prospective data across almost 2 decades and followed recent trends in relationship research by taking a developmental approach with a strong focus on the role of emotion dysregulation in interpersonal relationship quality (Conger et al., 2000). To date, only a few studies have used long-term prospective data to examine the intergenerational associations of romantic relationship conflict (e.g., Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Conger et al., 2000). The current study expanded on the existing literature by: (a) using a prospective longitudinal data that spanned the time from the son’s late childhood through young adulthood; (b) focusing on developmental origins of interpersonal functions, and (c) employing multiagent (e.g., self-report, parent report, teacher report, official records) and multimethod (e.g., interview, questionnaire, observation, ratings) data. By beginning to clarify the role of parents’ emotion dysregulation and poor discipline skills, this study helps to elucidate potential targets for preventive intervention in the transmission of relationship conflict. One of the most promising approaches may be to help parents experiencing relationship conflict to develop both stronger self-regulatory mechanisms and more effective parenting practices. Through this approach, it may be possible to break intergenerational cycles of relationship conflict and strengthen the behavioral and emotional regulatory abilities of future generations.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was provided by Grant HD 46364 from the Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and Division of Epidemiology, Services, and Prevention Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Public Health Service (PHS); Grant DA 051485 from the Division of Epidemiology, Services, and Prevention Branch, NIDA, and the Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development, NICHD, NIH, U.S. PHS; and Grant MH 37940 from the Psychosocial Stress and Related Disorders, National Institute of Mental Health, U.S. PHS.

Footnotes

At OYS wave 5 from which parents’ relationship conflict data were taken, 56% of the parents were married, 13% were cohabiting with a partner, and 31% were single. We conducted a mean comparison test by different marital status to examine whether parents’ relationship conflict varied depending on their marital status. Findings indicated that there was no significant group difference (F=.495 (df=2), p = .61).

A mean comparison test indicated a significant difference in son’s relationship conflict by their relationship status (married, cohabiting, and dating). Dating men reported lower levels of relationship conflict than married and cohabiting men. Married and cohabiting men reported similar levels of relationship conflict. Similarly, men’s length relationship was positively related to their relationship conflict (r=.18, p > .05). However, both relationship variables were not included in the model, as they were confounded with the sons’ ages which were included in the model.

References

- Achenbach TM. Young Adult Behavior Checklist. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1993a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Young Adult Self-Report. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1993b. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and the revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver KM, Wright JP, Delisi M. Self-Control as an Executive Function: Reformulating Gottfredson and Hirschi's Parental Socialization Thesis. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2007;34:1345–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen M. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Gill KL, Johnson MC, Smith CL. Emotional reactivity and emotional regulation strategies as predictors of social behavior with peers during toddlerhood. Social Development. 1999;8:310–334. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavioral problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:113–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1175–1188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, King J, Wilson J. Young Adult Adjustment Scale. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1992. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Pears KC, Kerr DCR, Owen LD. Intergenerational and partner influences on fathers′ negative discipline. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9182-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Cinanni V, D′Imperio G, Passerini S, Renzi P, Travaglia G. Indicators of impulsive aggression: Present status of research on irritability and emotional susceptibility scales. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Bem DJ, Elder GH., Jr Continuities and consequences of interactional styles across the life course. Journal of Personality. 1989;57:375–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Steinberg L, Piquero AR. Psychological, neuropsychological and physiological correlates of serious antisocial behavior in adolescence: The role of self-control. Criminology. 2005;43:133–175. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Ackerman B, Izard C. Emotions and emotion regulation in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Ganiban J, Barnett D. Contributions from the study of high-risk populations to understanding the development of emotion regulation. In: Garber J, Dodge K, editors. The Development of emotion regulation. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 15–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Cui M, Bryant CM, Elder GH., Jr Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM, Lekka SK. Pathways from marital aggression to infant emotion regulation: The development of withdrawal in infancy. Infant Behavior & Development. 2007;30:97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cupach WR, Olson LN. Emotion regulation theory: A lens for viewing family conflict and violence. In: Braithwaite DO, Baxte LA, editors. Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2006. pp. 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cummings M. Interdependencies among interparental discord and parenting practices: The role of adult vulnerability and relationship perturbations. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:773–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Reid JB, Capaldi DM, Forgatch MS, McCarthy S. Child Telephone Interview. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1984. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani TJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Emotion, regulation and the development of social competence. In: Clark MS, editor. Review of personality and social psychology: Vol. 14. Emotion and social behavior. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Embry L, Dawson G. Disruptions in parenting behavior related to maternal depression: Influences on children's behavioral and psychobiological development. In: Borkowski JG, Ramey SL, editors. Parenting and the child's world: Influences on academic, intellectual, and socio-emotional development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauchier A, Margolin G. Affection and conflict in marital and parent-child relationships. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2004;30:197–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Sharkansky EJ, Brandt KM, Turcotte N. The effects of familial risk, personality, and expectancies on alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:122–133. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganiban JM, Spotts EL, Lichtenstein P, Khera GS, Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM. Can genetic factors explain the spillover of warmth and negativity across family relationships? Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:299–313. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Evidence for dorsolateral and orbital prefrontal cortical involvement in the expression of aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior. 1995;21:431–450. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, D’Onofrio BM, Slutske WS, Heath AC, Martin NG. Marital conflict and conduct problems in children of twins. Child Development. 2007;78:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DM, Curry CJ, Bray JH. Individuation and intimacy in intergenerational relationships and health: Patterns across two generations. Journal of Family Psychology. 1991;5:204–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, revised. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Department of Sociology, Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins RL. Varieties of children's behavior problems and family dynamics. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1972;124:1440–1445. doi: 10.1176/ajp.124.10.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The national comorbidity survey. DIS Newsletter. 1990;7(12):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsfogel KM, Grych JH. Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationships: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and peer influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:505–515. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong MJ, Bartholomew K, Henderson AJZ, Trinke S. The intergenerational transmission of relationship violence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:288–301. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Christensen A, John RS. The continuance and spillover of everyday tensions in distressed and nondistressed families. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:304–321. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Lynch KG, Pollock NK, Clark DB. Gender differences and similarities in the personality correlates of adolescent alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:121–133. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan A, Cicchetti D. Impact of child maltreatment and interadult violence on children's emotion regulation abilities and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73:1525–1542. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BC, Shepard SA, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Concurrent and across time prediction of young adolescents’ social functioning: The role of emotionality and regulation. Social Development. 2004;13:56–86. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 5th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Smith Slep AM, O’Leary SG. Multivariate models of men's and women's partner aggression. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:752–764. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Social Learning Center. Family Interaction Task FPC Coder Ratings. Eugene: Author; 1984. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Social Learning Center. Interviewer Ratings. Eugene: Author; 1984–1987. Unpublished instruments. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Bank L. Bootstrapping your way in the nomological thicket. Behavioral Assessment. 1986;8:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Capaldi DM, Owen LD. Substance use risk across three generations: The roles of parent discipline practices and inhibitory control. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:373–386. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):87–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz MS, Waldinger RJ, Hauser ST, Allen JP. Adolescents’ behavior in the presence of interparental hostility: Developmental and emotion regulatory influence. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:489–507. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Collins WA, Tran S, Haydon KC. Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:355–367. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:906–916. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: STAI (Form Y) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Emotional development: The organization of emotional life in the early years. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Story LB, Karney BR, Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Interpersonal mediators in the intergenerational transmission of marital dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:519–529. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Waldinger RJ, Schultz MS, Allen JP, Crowell JA, Hauser ST. Prospective associations from family of origin interactions to adult marital interactions and relationship adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:274–286. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]