Abstract

Cancer metastasis is the life-threatening aspect of cancer and is usually resistant to standard treatment. We report here a targeted therapy strategy for cancer metastasis using a modified strain of Salmonella typhimurium. The genetically modified strain of S. typhimurium is auxotrophic for the amino acids arginine and leucine. These mutations preclude growth in normal tissue but do not reduce bacterial virulence in tumor cells. The tumor-targeting strain of S. typhimurium, termed A1-R and expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP), was administered to both axillary lymph and popliteal lymph node metastasis of human pancreatic cancer and fibrosarcoma, respectively, as well as lung metastasis of the fibrosarcoma in nude mice. The bacteria were delivered via a lymphatic channel to target the lymph-node metastases and systemically via the tail vein to target the lung metastasis. The cancer cells expressed red fluorescent protein (RFP) in the cytoplasm and GFP in the nucleus linked to histone H2B, enabling color-coded real-time imaging of the bacteria targeting the metastatic tumors. After 7–21 days of treatment, the metastases were eradicated without the need of chemotherapy or any other treatment. No adverse effects were observed. This new strategy demonstrates the clinical potential of targeting and curing cancer metastasis with engineered bacteria without the need of toxic chemotherapy.

Keywords: Salmonella typhimurium, green fluorescent protein, lymph node metastasis, red fluorescent protein

INTRODUCTION

It has been known for approximately 60 years that anaerobic bacteria can selectively grow in tumors [Coley, 1906; Malmgren and Flanigan, 1955; Moese and Moese, 1964; Gericke and Engelbart, 1964; Thiele et al., 1964; Kohwi et al., 1978; Brown and Giaccia, 1998; Fox et al., 1996; Lemmon et al, 1997; Sznol et al., 2000; Low et al., 1999; Clairmont et al., 2000; Yazawa et al., 2000; Yazawa et al., 2001; Kimura, et al., 1980]. The conditions that permit anaerobic bacterial growth (i.e., impaired circulation and extensive necrosis) are found in many tumors. Several approaches to developing tumor-therapeutic anaerobic bacteria have been described. Yazawa et al. [2000; 2001] showed that the anaerobic bacterium Bifidobacterium longum could selectively grow in the hypoxic regions of solid tumors. Dang et al. [2001] created a strain of Clostridium novyi depleted of its lethal toxin (C. novyi-NT). C. novyi spores germinated within the avascular regions of tumors in mice and destroyed surrounding viable tumor cells [Dang et al., 2001]. The main efficacy of these anaerobic bacteria was in combination with chemotherapy [Dang et al., 2001]. Eradication of tumors was also achieved in mice by combining C. novyi-NT with radiation [Bettegowda et al., 2003]. It was recently shown that treatment of mice bearing large, established tumors with C. novyi-NT plus a single dose of liposomal doxorubicin could lead to eradication of the tumors. The bacterial factor responsible for the enhanced drug release was identified as a protein termed liposomase [Cheong et al., 2006; Juliano, 2007].

The facultative anaerobe Salmonella typhimurium was first attenuated by purine and other auxotrophic mutations to be used for cancer therapy [Low et al., 1999; Hoiseth and Stocker, 1981; Pawelek et al., 1997]. These bacteria replicated in the tumor to >1,000-fold compared with normal tissues [Low et al., 1999]. Salmonella lipid A was also genetically modified by disrupting the msbB gene to reduce septic shock [Low et al., 1999]. Melanomas in mice treated with the Salmonella msbB mutant were 6% the size of tumors in untreated controls [Low et al., 1999]. However, these Salmonella variants did not cause tumor regression or eradication, only growth inhibition. S. typhimurium with attenuated lipid A has been evaluated in a Phase I clinical trial [Toso, et al., 2002].

We have previously developed [Zhao et al., 2005] a genetically modified bacterial strain of S. typhimurium, auxotrophic for leucine and arginine, which also expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP), termed S. typhimurium A1. When introduced i.v. or intratumorally, A1 invaded and replicated intracellularly in various cancer cells in vivo as well as in vitro. When A1 was injected intratumorally, the tumor completely regressed by day 20. There were no obvious adverse effects on the host when the bacteria were injected i.v. or intratumorally. The S. typhimurium A1 strain grew throughout the tumor, including viable malignant tissue, but could not sustain growth in normal tissue. This result is in marked contrast to the anaerobic bacteria evaluated previously for cancer therapy that were confined to necrotic areas of the tumor as discussed above. The ability to grow in viable tumor tissue may account, in part, for the unique antitumor efficacy of the A1 strain [Zhao et al., 2005].

The A1-R strain was reisolated from A1-targeted tumor tissue in vivo. The idea was to increase the tumor targeting capability of the bacteria. As a consequence of this selective step, the tumor-cell targeting of the reisolated A1 increased in vivo as well as in vitro. The reisolated A1 bacteria, termed A1-R, administered i.v., resulted in human breast cancer [Zhao et al., 2006] and prostate cancer [Zhao et al., 2007] regression, including tumor eradication in orthotopic nude-mouse models.

Cancer metastasis is the life threatening aspect of cancer. Importantly, metastasis is most often treatment-resistant. In the present study, we demonstrate that S. typhimurium A1-R can directly target and eradicate cancer metastases demonstrating the potential of bacterial therapy to treat otherwise incurable disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. typhimurium A1-R therapy of cancer cells in vitro

XPA1 and HT-1080 cells labeled with RFP in the cytoplasm and GFP in the nucleus were grown in 24-well tissue culture plates to a density of 104 cells per well. Bacteria were grown in LB and harvested at late-logarithmic phase, diluted in cell culture medium and added to the tumor cells (1 × 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per well). After 1 h incubation at 37°C, the cells were rinsed and cultured in medium containing gentamycin sulfate (20 μg/ml) to kill external but not internal bacteria. Interaction between bacteria and tumor cells was observed at the indicated time points. An Olympus BH 2-RFCA fluorescence microscope equipped with a mercury 100-W lamp power supply and GFP filter set (Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT) was used for fluorescence microscopy.

S. typhimurium A1-R therapy of experimental lymph node metastasis

To obtain metastasis in the axillary lymph node, XPA1-RFP cells were injected into the inguinal lymph node (afferent lymph node to the axillary) in nude mice. Nudemice were anesthetized with a ketamine mixture (10 μLketamine HCL, 7.6 μL xylazine, 2.4 μL acepromazine maleate, and 10 μL H2O) via s.c. injection. A one-cm incision was made in the abdominal skin to expose the inguinal lymph node. The inguinal lymph node was exposed without injuring the lymphatic. The skin was fixed on a flat stand. A total of 10 μL medium containing 5 × 105 cancer cells was injected into the center of the inguinal lymph node. Just after injection, cancer cells were observed trafficking in the efferent lymph duct toward the axillary lymph node. Seven days later (day 0), mice were anesthetized, and the axillary lymph node was observed for metastasis. A two-cm incision was made at the center of the chest wall. The greater pectoral muscle was released from the sternum to expose the axillary lymph node. The connective tissue on the axillary lymph node was separated. The lymph node was imaged for metastasis. Lymph nodes which had less than a one-mm tumor were included in this study. Five mice were treated with A1-R, and 5 were used as controls for each cell line. A1-R bacteria (108 CFU) were injected in the inguinal lymph node. After injection, the axillary lymph node was observed repeatedly at different time points with the Olympus OV100 Small-Animal Imaging System (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The size of metastasis (fluorescent area [mm2]) was measured at each imaging time point.

S. typhimurium A1-R therapy therapy of spontaneous lymph node metastasis

To obtain spontaneous lymph node metastasis, 5 × 106 HT-1080-GFP-RFP cells in 20 μl of Matrigel basement membrane matrix (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) were injected into the foot pad in nude mice. The presence of popliteal lymph node metastasis was determined by fluorescence imaging every week after tumor injection. Mice were given the ketamine mixture for anesthesia and laid out in the prone position. The entire limb was observed with the OV100 imaging system without any traumatic procedures. Once metastasis was confirmed in the popliteal region, bacteria therapy was started targeting the metastasis (day 0). A1-R bacteria (108 CFU) were injected subcutaneously in the foot pad. The size of metastasis and primary tumor, and body weight was measured every week. Six mice were treated with A1-R, and 6 were used as controls. Another two mice were used for imaging immediately and at day-7 after bacteria injection. The experiment was terminated when the control primary tumor invaded the popliteal region or the mouse died. The experimental data are expressed as the mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was done using the two-tailed Student’s t-test.

S. typhimurium A1-R therapy of experimental lung metastasis

Four week old, female nude mice were used. To obtain lung metastasis, HT-1080-GFP-RFP cells (1 × 106 in 100μl PBS) were injected into the tail vein of the nude mice (day 0). On day 4 and day 11, 5 × 107 CFU bacteria per mouse were injected into the tail vein. Five mice were treated with bacteria and five mice were used as untreated control. On day16, all animals were sacrificed and the lungs were imaged to determine the efficacy of bacteria therapy for lung metastasis. To observe the lung metastasis at lower magnification, an RFP filter was used (excitation 545 nm, emission 570–625 nm).

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under assurance no. A3873-1.

Statistical analysis

The total number of metastases on the surface of the lung was counted using the Olympus OV100 Small Animal Imaging System (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The pictures were taken in same setting (exposure time 1000 msec, 0.56×lens). The number of metastases in each group was expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was done using the two-tailed Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

S. typhimurium A1-R therapy of cancer cells in vitro

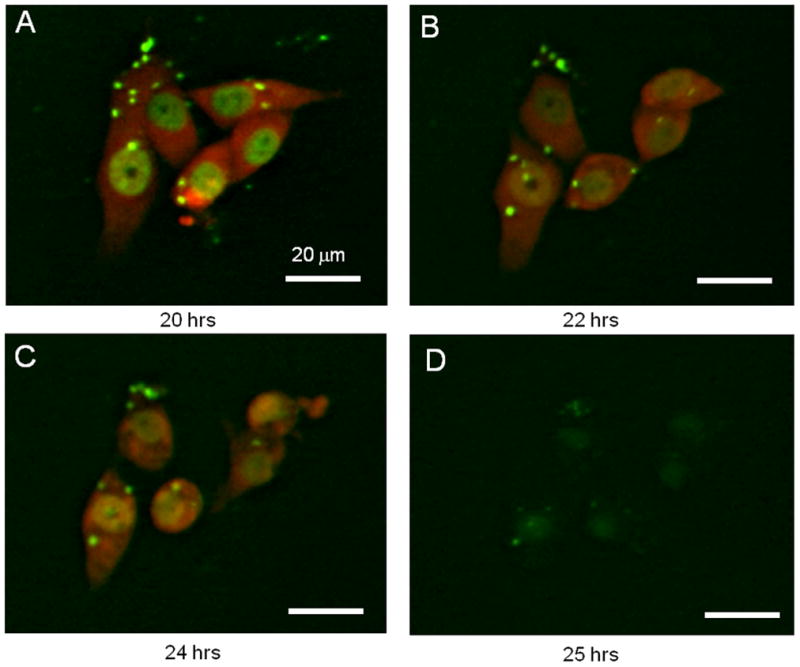

We first tested the ability of S. typhimurium A1-R to kill human pancreatic cancer and fibrosarcoma cells in vitro. A1-R expressing GFP was observed to invade and replicate intracellularly in the XPA1 human pancreatic cancer and HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cell lines expressing GFP in the nucleus and RFP in the cytoplasm. Intracellular bacterial infection led to cell fragmentation and rapid cell death (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Targeting of tumor cells by S. typhimurium A1-R in vitro.

XPA1 human pancreatic cancer cells labeled with RFP in the cytoplasm and GFP in the nucleus [Yamamoto et al., 2004] were grown in 24-well tissue culture plates. Bacteria were added to the tumor cells (1 × 105 CFU per well). After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, the cells were rinsed and cultured in medium containing gentamycin sulfate (20 μg/ml) to kill external but not internal bacteria. Interaction between bacteria and tumor cells was observed at the indicated time points under fluorescence microscopy. (A to D) GFP-expressing S. typhimurium A1-R was able to invade and replicate intracellularly in the dual-color XPA1 cell line in vitro. The cytopathic effects of A1-R on XPA1 cells after infection were visible using dual-color fluorescence. Intracellular bacterial infection leading to eventual cell fragmentation and cell death was observed. Bars, 20 μm.

S. typhimurium A1-R therapy of experimental lymph-node metastasis

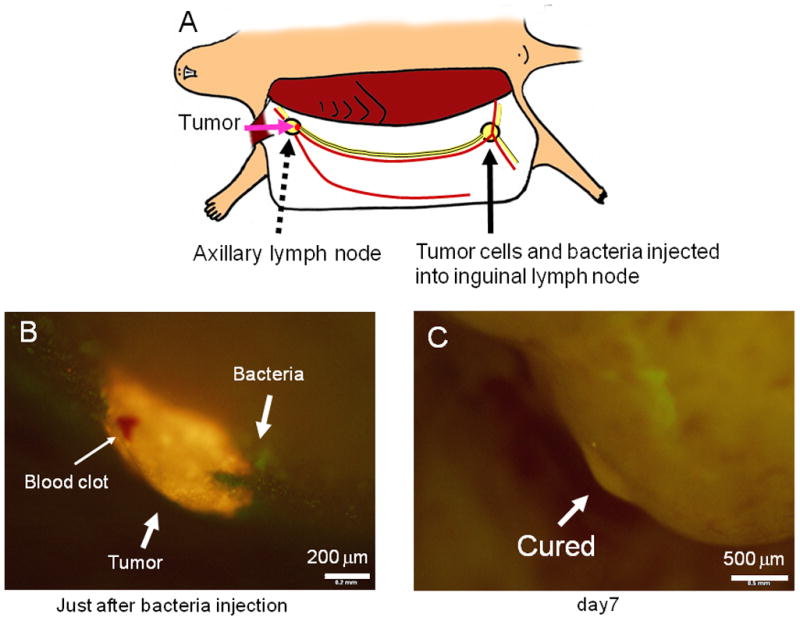

A new experimental model of lymph node metastasis was developed for this study. To obtain an experimental metastasis in the axillary lymph node, XPA1-RFP human pancreatic cancer cells were injected into the inguinal lymph node in the nude mice (Fig. 2A). Just after injection, cancer cells were imaged trafficking in the efferent lymph duct to the axillary lymph node [Hayashi et al., 2007]. Metastasis in the axillary lymph node was subsequently formed. A1-R bacteria were then injected into the inguinal lymph node to target the axillary lymph node metastasis. Just after bacterial injection, a large amount of bacteria were visualized around the axillary lymph node metastasis (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Movie-1). By day 7, all lymph node metastases had been eradicated in contrast to growing metastases in the control group (Figs. 2C and 3). There were very few bacteria in the lymph node by day 7, and no bacteria were detected after day 10. This route of administration was therefore able to deliver sufficient bacteria to eradicate the lymph node metastasis after which the bacteria became undetectable.

Fig. 2. Targeted therapy of experimental lymph node metastasis with S. typhimurium A1-R.

(A) Scheme for experimental lymph node metastasis model. Cancer cells were injected into the inguinal lymph node. After injection, the cells trafficked to the axillary lymph node and formed metastases. Small skin incisions were made around both the inguinal lymph node and axillary lymph node for purposes of imaging. (B) Seven days after XPA1-RFP human pancreas cancer cell injection in the inguinal lymph node, an experimental metastasis was observed in axillary lymph node. After A1-R was injected in the inguinal lymph node, bacteria were imaged around the tumor in the axillary lymph node. (C) Seven days after bacteria injection, the metastasis has been eradicated.

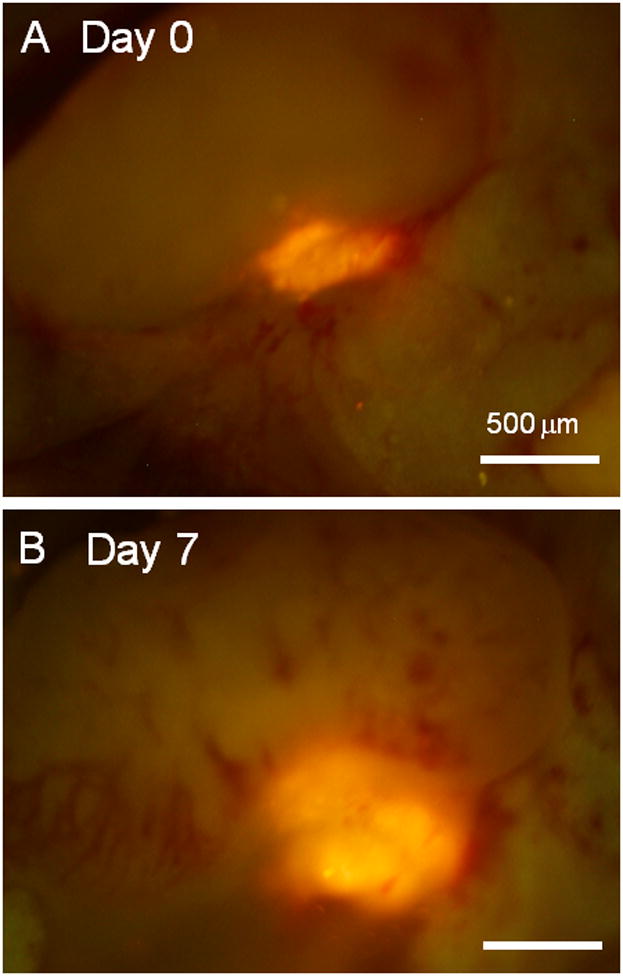

Fig. 3. Growth of axillary-lymph-node metastasis in untreated animals.

(A) Seven days after XPA1-RFP human-pancreas-cancer cell injection in the inguinal lymph node (day 0), metastasis was observed in the axillary lymph node. (B) On day 7, the metastasis was growing in contrast to the treatment group where the metastases were eradicated.

The average tumor size (fluorescent area) in the axillary lymph nodes on day 0 was 0.4 ± 0.19 mm2 in the treatment group and 0.46 ± 0.08 in the untreated group, respectively. On day 7, it was 0 mm2 in the treatment group and 0.98 ± 0.17 in the untreated group.

S. typhimurium A1-R therapy of spontaneous lymph node metastasis

We then tested bacterial therapy strategy for spontaneous lymph node metastasis from a tumor growing in the footpad. At first, only A1-R bacteria were injected in the foot pad in nude mice in order to determine any adverse effects. No infection, skin necrosis, or body weight loss or fatality was detected (data not shown). Then HT1080-GFP-RFP human fibrosarcoma cells were injected into the footpad of additional nude mice. Before treatment, the presence of popliteal lymph node metastasis was determined by weekly imaging. Once the metastasis was detected, A1-R bacteria were injected subcutaneously in the footpad.

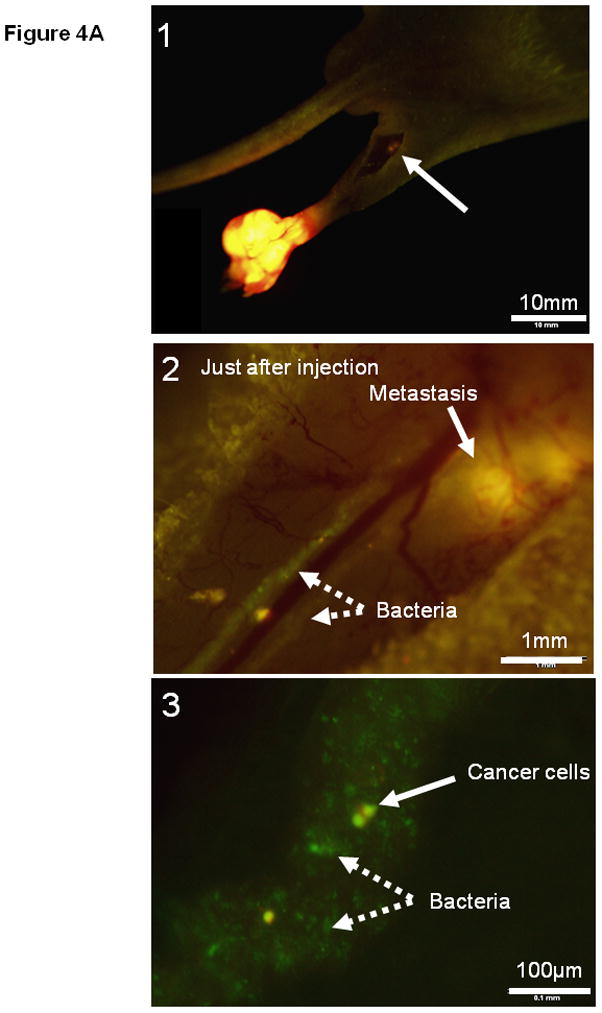

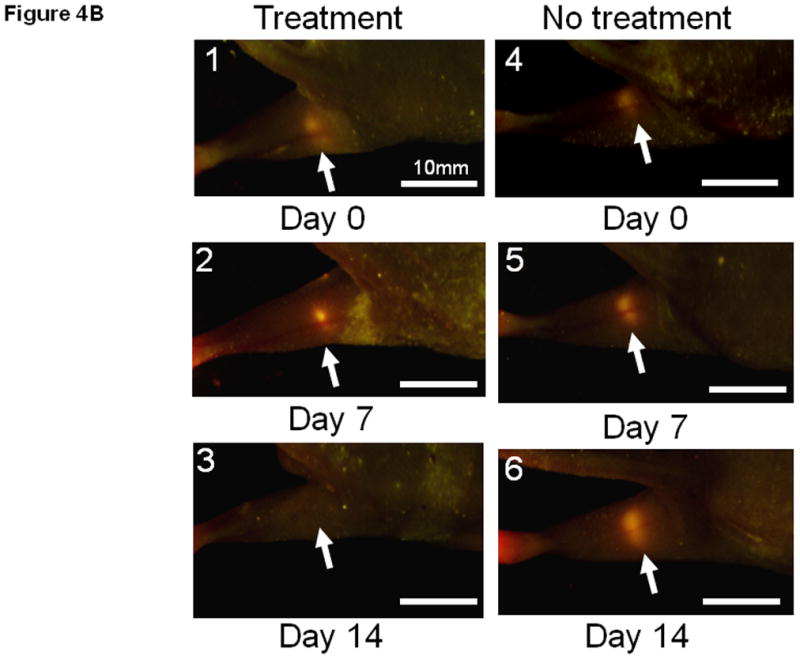

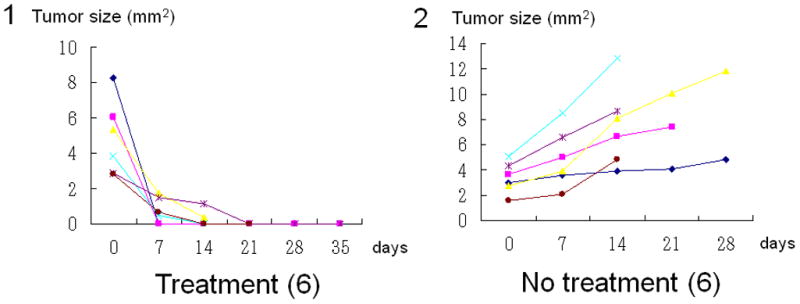

Bacteria are small particles and when injected subcutaneously, the lymph system immediately collects them from the site of injection. The lymph system is well known as a drainage route for bacterial infection. One mouse was used to observe the injected bacteria trafficking in the lymphatic channel. The popliteal region was exposed just after bacteria injection and a large amount of GFP bacteria targeting the popliteal lymph node metastasis was observed by fluorescence imaging (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Movie-2). Dual-color labeling of the cancer cells distinguished them from the GFP bacteria. After treatment, the popliteal lymph node was observed every week by fluorescence imaging. One mouse was used to image the bacteria by exposing the popliteal lymph node on day 7. All lymph node metastases shrank and 5 out of 6 were eradicated within 7 to 21 days after treatment in contrast to growing metastases in the control group (Fig. 4B and C).

Fig. 4. Targeted therapy of spontaneous popliteal lymph node metastasis with S. typhimurium A1-R.

(A1) Dual color HT-1080 human fibrosarcoma cells were injected into the foot pad in nude mice. The popliteal lymph node metastasis was imaged every week after cancer-cell injection. Once metastasis was visualized in the popliteal region (arrow), bacterial therapy was started to target the metastasis. (A2) Bacteria were injected subcutaneously in the foot pad. The popliteal lymph node was exposed to image bacteria trafficking. GFP bacteria were observed in lymphatic channels connecting the popliteal lymph node. (A3) Higher magnification of lymphatic channel. GFP bacteria and dual color cancer cells are readily distinguished. (B1–B6) Representative weekly images of the popliteal lymph node metastasis after bacteria injection. (B1–B3) 0, 7 and 14 days after bacteria injection. The lymph node metastasis has been eradicated by 14 days. (B4–B6) 0, 7 and 14 days for control (no bacteria treatment). The lymph node metastasis continues to grow. (C1–C2) All lymph node metastases have regressed and 5 out of 6 are eradicated within 7 to 21 days after treatment in contrast to growing tumors in the control group.

S. typhimurium therapy for lung metastasis

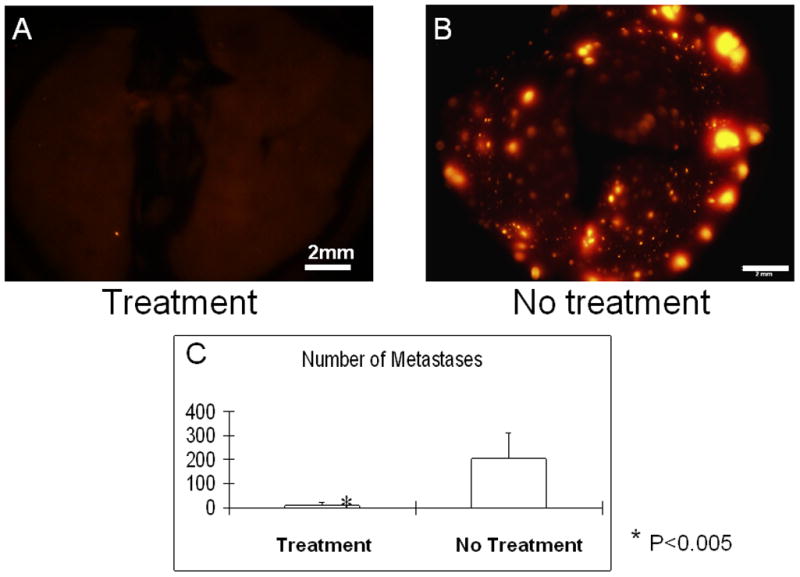

To obtain lung metastasis, dual-colored HT-1080 cells were injected into tail vein of the nude mice (day 0). On day 4 and day 11, bacteria were injected into the tail vein. On day 16, all animals were sacrificed and the lungs were imaged to determine the effect of bacteria therapy on lung metastasis. To observe the lung metastasis at lower magnification, an RFP filter was used (excitation 545 nm, emission 570–625 nm). In the bacterial-treatment group, only a few cancer cells were observed in contrast to multiple metastases in the control (untreated) group (Fig. 5A and B). The number of metastases on the surface of the lung was significantly lower in the treatment group than in the control group (P<0.005) (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. Targeted therapy of experimental lung metastasis with S. typhimurium A1-R.

To obtain lung metastasis, dual-colored HT-1080 cells were injected into the tail vein of nude mice (day 0). On day 4 and day 11, bacteria were injected into the tail vein. On day 16, all animals were sacrificed and the lungs were imaged to determine the effect of bacteria therapy on lung metastasis. To observe the lung metastasis at lower magnification, an RFP filter was used (excitation 545 nm, emission 570–625 nm). In the bacterial treatment group, only a few cells were observed (A) in contrast to multiple metastases in the control (non-treatment) group (B). The number of metastases on the surface of the lung was significantly lower in the treatment group than in the control group (P<0.005) (C).

Effect of S. typhimurium on body weight

There were no significance differences between the treated and untreated groups in body weight and primary tumor size (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Effect of bacterial therapy on body weight

| Treatment | No Treatment | T-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up (days) | 27.3 ± 9.9 | 25.5 ± 8.8 | 0.74 |

| Body weight – day-0 (g) | 21.4 ± 4.6 | 20.3 ± 0.94 | 0.59 |

| Body weight – last day of treatment | 22.5 ± 21.7 | 21.7 ± 1.2 | 0.66 |

S. typhimurium A1-R was used to treat nude mice with metastatic cancer as described in the Materials and Methods. In the course of bacterial treatment of the spontaneous lymph-node metastasis, there were no significant differences between the treated and untreated groups in body weight or primary tumor size in the foot pad.

DISCUSSION

The strategy employed in our studies for bacterial therapy of cancer has significant advantages over that using obligate anaerobic bacteria such as Clostridium. Anaerobic bacteria only grow in the necrotic regions of tumors and therefore require additional cytotoxic chemotherapy in order to kill viable tumor tissue and effect eradication [Dang et al., 2001]. The facultative anaerobic S. typhimurium, in contrast, grows in viable as well as necrotic regions of tumors and therefore can eradicate tumors without additional chemotherapy. Thus, our method of bacterial treatment can target spontaneous metastasis and eradicate them without toxic chemotherapy, a major advance over other approaches to bacterial therapy which require combination with chemotherapy in order to effect eradication [Cheong et al., 2006; Juliano, 2007]. For lymph node metastasis, we used a lymphatic targeting approach that was highly effective. The lung metastases in our model were eradicated by systemic injection. However, no adverse effects were observed.

The lymphatic system is a critical route for both bacteria drainage and cancer spread. In humans, subcutaneous injection of tumor-targeting bacteria around the primary tumor should be an effective way to target lymphatic metastasis. Alternatively, the tumor-targeting bacteria can be injected directly in the lymph duct similar to lymphangiography. The bacteria could then reach regional lymph nodes and potentially eradicate the metastasis. The adverse effects should be much less than systemic administration. Intralymphatic administration of bacteria in humans should require only low doses of bacteria.

Supplementary Material

GFP-labeled S. typhimurium A1-R are seen trafficking in a lymphatic duct to the axillary lymph node metastasis of the XPA1-RFP pancreatic cancer cell line. The bacteria were injected in the inguinal lymph node. Real time images were obtained with the Olympus OV100 Small Animal Imaging System. The lymph duct was exposed with a skin-flap.

GFP-labeled S. typhimurium A1-R are seen trafficking in a lymphatic duct to the popliteal lymph node metastasis of the HT1080-GFP-RFP human fibrosarcoma cell line. The bacteria were injected in the foot pad. Real time images were obtained with the Olympus OV100 Small Animal Imaging System. The lymph duct was exposed with a skin-flap.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant CA119841 and U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program contract award W81XWH-06-1-0117.

References

- Bettegowda C, Dang LH, Abrams R, Huso DL, Dillehay L, Cheong I, Agrawal N, Borzillary S, McCaffery JM, Watson EL, Lin KS, Bunz F, Baidoo K, Pomper MG, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S. Overcoming the hypoxic barrier to radiation therapy with anaerobic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15083–15088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036598100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Giaccia AJ. The unique physiology of solid tumors: opportunities (and problems) for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1408–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong I, Huang X, Bettegowda C, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW, Zhou S, Vogelstein B. A bacterial protein enhances the release and efficacy of liposomal cancer drugs. Science. 2006;314:1308–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1130651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clairmont C, Lee KC, Pike J, Ittensohn M, Low KB, Pawelek J, Bermudes D, Brecher SM, Margitich D, Turnier J, Li Z, Luo X, King I, Zheng LM. Biodistribution and genetic stability of the novel antitumor agent VNP20009, a genetically modified strain of Salmonella typhimurium. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1996–2002. doi: 10.1086/315497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley WB. Late results of the treatment of inoperable sarcoma by the mixed toxins of Erysipelas and Bacillus prodigosus. Am J Med Sci. 1906;131:375–430. [Google Scholar]

- Dang LH, Bettegowda C, Huso DL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Combination bacteriolytic therapy for the treatment of experimental tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15155–15160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251543698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox ME, Lemmon MJ, Mauchline ML, Davis TO, Giaccia AJ, Minton NP, Brown JM. Anaerobic bacteria as a delivery system for cancer gene therapy: in vitro activation of 5-fluorocytosine by genetically engineered clostridia. Gene Ther. 1996;3:173–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gericke D, Engelbart K. Oncolysis by clostridia. II. Experiments on a tumor spectrum with a variety of clostridia in combination with heavy metal. Cancer Res. 1964;24:217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Jiang P, Yamauchi K, Yamamoto N, Tsuchiya H, Tomita K, Moossa AR, Bouvet M, Hoffman RM. Real-time imaging of tumor-cell shedding and trafficking in lymphatic channels. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8223–8228. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiseth SK, Stocker BA. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano R. Bugging tumors to put drugs on target. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:954–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr067638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura NT, Taniguchi S, Aoki K, Baba T. Selective localization and growth of Bifidobacterium bifidum in mouse tumors following intravenous administration. Cancer Res. 1980;40:2061–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohwi Y, Imai K, Tamura Z, Hashimoto Y. Antitumor effect of Bifidobacterium infantis in mice. Gann. 1978;69:613–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon MJ, van Zijl P, Fox ME, Mauchline ML, Giaccia AJ, Minton NP, Brown JM. Anaerobic bacteria as a gene delivery system that is controlled by the tumor microenvironment. Gene Ther. 1997;4:791–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low KB, Ittensohn M, Le T, Platt J, Sodi S, Amoss M, Ash O, Carmichael E, Chakraborty A, Fischer J, Lin SL, Luo X, Miller SI, Zheng L, King I, Pawelek JM, Bermudes D. Lipid A mutant Salmonella with suppressed virulence and TNFalpha induction retain tumor-targeting in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:37–41. doi: 10.1038/5205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmgren RA, Flanigan CC. Localization of the vegetative form of Clostridium tetani in mouse tumors following intravenous spore administration. Cancer Res. 1955;15:473–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moese JR, Moese G. Oncolysis by clostridia. I. Activity of Clostridium butyricum (M-55) and other nonpathogenic clostridia against the Ehrlich carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1964;24:212–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelek JM, Low KB, Bermudes D. Tumor-targeted Salmonella as a novel anticancer vector. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4537–4544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sznol M, Lin SL, Bermudes D, Zheng LM, King I. Use of preferentially replicating bacteria for the treatment of cancer. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1027–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI9818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele EH, Arison RN, Boxer GE. Oncolysis by clostridia. III. Effects of clostridia and chemotherapeutic agents on rodent tumors. Cancer Res. 1964;24:222–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toso JF, Gill VJ, Hwu P, Marincola FM, Restifo NP, Schwartzentruber DJ, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Yang JC, Stock F, Freezer LJ, Morton KE, Seipp C, Haworth L, Mavroukakis S, White D, MacDonald S, Mao J, Sznol M, Rosenberg SA. Phase I study of the intravenous administration of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium to patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:142–152. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Jiang P, Yang M, Xu M, Yamauchi K, Tsuchiya H, Tomita K, Wahl GM, Moossa AR, Hoffman RM. Cellular dynamics visualized in live cells in vitro and in vivo by differential dual-color nuclear-cytoplasmic fluorescent-protein expression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4251–4256. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazawa K, Fujimori M, Amano J, Kano Y, Taniguchi S. Bifidobacterium longum as a delivery system for cancer gene therapy: selective localization and growth in hypoxic tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:269–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazawa K, Fujimori M, Nakamura T, Sasaki T, Amano J, Kano Y, Taniguchi S. Bifidobacterium longum as a delivery system for gene therapy of chemically induced rat mammary tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;66:165–170. doi: 10.1023/a:1010644217648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Yang M, Li XM, Jiang P, Baranov E, Li S, Xu M, Penman S, Hoffman RM. Tumor-targeting bacterial therapy with amino acid auxotrophs of GFP-expressing Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:755–760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408422102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Yang M, Ma H, Li X, Tan X, Li S, Yang Z, Hoffman RM. Targeted therapy with a 2006. Salmonella typhimurium leucine-arginine auxotroph cures orthotopic human breast tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res. 66:7647–7652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Geller J, Ma H, Yang M, Penman S, Hoffman RM. Monotherapy with a tumor-targeting mutant of Salmonella typhimurium cures orthotopic metastatic mouse models of human prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10170–10174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703867104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

GFP-labeled S. typhimurium A1-R are seen trafficking in a lymphatic duct to the axillary lymph node metastasis of the XPA1-RFP pancreatic cancer cell line. The bacteria were injected in the inguinal lymph node. Real time images were obtained with the Olympus OV100 Small Animal Imaging System. The lymph duct was exposed with a skin-flap.

GFP-labeled S. typhimurium A1-R are seen trafficking in a lymphatic duct to the popliteal lymph node metastasis of the HT1080-GFP-RFP human fibrosarcoma cell line. The bacteria were injected in the foot pad. Real time images were obtained with the Olympus OV100 Small Animal Imaging System. The lymph duct was exposed with a skin-flap.