Abstract

The effectiveness of a language-training procedure that emphasized reinforcing vocal “reasonable attempts” (any response directed at an interventionist and within a broader class of correct responses) was compared with a procedure that emphasized shaping (reinforcing successive approximations that more closely resembled the target vocalization). Three preschoolers who had been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders participated in the study. Data indicated that the children mastered vocal skills more rapidly when they learned through shaping than in the reasonable attempts condition. Implications for teaching children with autism spectrum disorders are discussed.

Keywords: shaping, reinforcement, verbal attempts

It is generally acknowledged that difficulty in acquiring language skills is a core deficit associated with the autism spectrum disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000); thus, this has been an area of considerable focus for clinicians (Rappaport, 2001). One approach that has been empirically verified as effective is a shaping-based model (Lovaas, 1977), often conducted within the teaching system known as discrete-trial teaching (DTT; Leaf & McEachin, 1999).

In the shaping model, vocal instructions and teaching stimuli are presented. Vocal responses that meet a previously established standard are reinforced. Traditionally, only responses as good as or better than those previously emitted are reinforced as the clinician attempts to shape more exact speech and functional language on the part of the student.

This procedure, although effective, is extremely labor intensive, may take many trials, and may use arbitrary stimuli that are not meaningful to the student. Students may not always be motivated by the teaching stimuli or situation, and avoidance behavior is sometimes observed. In addition, generalization does not usually occur without intensive programming. In view of these shortcomings, an alternate strategy of teaching language has been proposed. This strategy, often referred to as natural environment teaching, capitalizes on capturing motivating operations in the context of naturally occurring teaching opportunities. For example, teaching is conducted when the student leads the instructor to, approaches, or reaches for certain stimuli (e.g., Sundberg & Partington, 1998).

R. L. Koegel, O'Dell, and Dunlap (1988) have also suggested that traditional shaping methodologies associated with DTT should be modified so that the student's verbal attempts are also reinforced. R. L. Koegel et al. presented data that suggest that it is more efficient to reinforce approximations rather than to use a specific shaping method (what they call the motor speech condition, reinforcing only those speech topographies that are as good as or better than previous attempts). Schreibman, Stahmer, and Pierce (1996) describe how data obtained by R. L. Koegel et al. have influenced the approach to teaching:

In contrast to earlier training programs … the child is reinforced for “trying,” so that efforts to continue in the learning situation are increased. However, to be reinforced a response has to be “reasonable” in terms of being directed at the interventionist or training materials and within the broader class of correct responses. (p. 356)

R. L. Koegel et al. provided a set number of sessions of either motor speech shaping or reinforcing reasonable attempts. Their data indicated better affect on the part of students during the verbal attempts condition, as well as faster acquisition of speech. In fact, the researchers note that the subjects “either showed smaller improvements, no change, or deterioration in speech production in every instance when the motor speech condition was implemented” (p. 535). Other studies and reviews of the literature, however, have shown the effectiveness of shaping procedures. These are generally considered to be effective approaches (Anderson, Taras, & O'Malley-Cannon, 1996; Fleece et al., 1981), particularly when staff have been established as sources of reinforcement prior to the implementation of intensive teaching efforts (Leaf & McEachin, 1999).

In the current study, we attempted to determine which of the two teaching procedures (i.e., shaping or reinforcing reasonable attempts) is more effective. We implemented and compared these approaches by approximating existing teaching procedures in a preschool for children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. It should be noted that in so doing, we made the following substantial departures from the procedures employed by R. L. Koegel et al. (1988): (a) We conducted shaping sessions until a criterion of understandable speech was met, rather than for a preset number of sessions, and then yoked reasonable attempts to this value. (b) We examined a wider variety of vocal responses, including those that were more conversational and therefore did not necessarily include a naturally occurring tangible reinforcer. (c) Speech improvement was analyzed in terms of intelligibility rather than phonetic targets mastered, and was analyzed on a session-by-session basis. (d) We used 90% accuracy across three sessions and across two interventionists as the mastery criterion. This was the general mastery criterion in use at the preschool and would therefore closely approximate everyday teaching conditions.

METHOD

Participants

Three boys participated in the study. Max, James, and Al were all between the ages of 3 and 4.5 years old. All scored in the mild to moderate range of mental retardation as assessed by the Peabody Picture Vocabulary and Stanford-Binet intelligence tests. All students were described as “emerging verbal”; that is, they were capable of some vocal imitation or rote one- to three-word utterances.

Dependent Measures

Accuracy of responding on DTT programs was assessed for each student. The specific skills taught were verbal requesting of desired items, answering simple “wh–” questions to assess listening comprehension, answering basic social questions regarding personal information, filling in missing words, reciprocal conversation of social information, expressive identification of common objects, and expressive identification of simple shapes.

Research Design

For each student, we selected four DTT programs that represented skill acquisition in the areas described above. Eight words or phrases that would serve as the correct response were selected, with one response from each program being assigned to the shaping condition and the other to the reasonable attempts condition. We began by teaching each student with one program (e.g., requesting), shaping the correct verbal response to criterion. After mastery was achieved, we yoked the reasonable attempts condition using a second word or phrase from the same program area. In other words, we taught a new word or phrase, for the same number of sessions as it took to shape the first word or phrase. Programs included requesting, object identification, verbal identification of attributes, social questions, and reciprocal conversation. Programs were based on those in Romanczyk, Lockshin, and Matey (1996).

We used a reversal design to compare the effects of the two teaching methods. To control for order effects, we counterbalanced conditions for each student, beginning with the reasonable attempts condition, either to mastery criterion or for the same number of sessions as shaping in the first phase. Programs were comparable in each phase, although different vocalizations were targeted across phases. More specifically, social questions might be targeted through both shaping and reasonable attempts, but different vocal topographies were taught from the same program in each phase. For example, the student might be taught to answer his own name in the shaping condition and to answer his mother's name in the reasonable attempts condition.

To the maximum extent possible, naturally occurring reinforcers were used (e.g., supplying requested items as a naturally occurring reinforcer). When this was not possible, reinforcers were chosen from a reinforcer inventory, assessed via periodic stimulus preference assessments. Concurrent-operants choice assessments were conducted with each student based on Fisher et al. (1992). These assessments were performed on a regular basis as part of participants' educational programming independent of this study.

Independent Variable

Shaping

Reinforcement was provided for only those responses that were as good as or better than previously emitted responses. Teachers trained in DTT and shaping procedures judged the quality of the response compared to previous responses and determined when the response was considered to match the target set. Mastery criterion was set at 90% accuracy across three sessions and across two interventionists.

Reasonable attempts

Reinforcement was provided if the student directed a response at the interventionist or training materials and the response was one that might have been reinforced at any point if shaping were used to teach this skill (i.e., responding within a broader class of correct responses). Therefore, reinforcement was not contingent on equivalent or successively more accurate responses.

Programs

The following programs were conducted using both the shaping and reasonable attempts procedures:

Requesting

Staff had several items that had been established as preferred prior to the start of the study. The student was required to initiate, using a minimum of two words (e.g., “want [item]”). This was done incidentally, and there was no specific prompt provided by the interventionist.

“Wh–” questions

Staff provided information to the student from a story and then asked a “wh–” question (e.g., “Who went to the store?”). A one-word answer was required at minimum.

Reciprocal conversation

The staff member made a statement regarding him- or herself, and the student was required to make a corresponding statement regarding himself (e.g., staff said “I have Grover,” and the student responded, “have Elmo”). A two-word answer was required at minimum.

Social questions

Staff asked the student a question regarding personal information (e.g., “What is your name?”). A one-word answer was required at minimum.

Object identification

Staff pointed to an item and said “What's that?” A one-word answer was required at minimum.

Fill-ins

Staff read a passage to a student from a preferred story. The interventionist then read it again, pausing at a key point to allow the student to fill in the missing word.

Shape identification

Staff pointed to individual shapes and asked the student to vocalize the label of the shape. A one-word answer was required at minimum.

Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement data were collected on approximately 40% of sessions. Agreements were defined as occurrences in which both observers recorded a response as correct or incorrect. Disagreements were defined as occurrences in which one observer recorded a response as correct, and the other recorded the same response as incorrect. Mean interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing agreements by agreements plus disagreements, then multiplying by 100%. Treatment integrity data were also collected by an independent observer on adherence to the reinforcement condition (i.e., shaping vs. reinforcement of reasonable responses) on every trial. Mean treatment integrity was 81%, and mean interobserver agreement was 89%. Of note, all disagreements pertained to the identification of reasonable attempts (see discussion).

RESULTS

Figures 1 through 3 depict the participants' performances under both the shaping and the reasonable attempts conditions. In the majority of phases, mastery criteria were reached more quickly during the shaping conditions.

Figure 1.

Percentage of correct verbal responses across shaping (S) and reasonable attempts (RA) conditions for James.

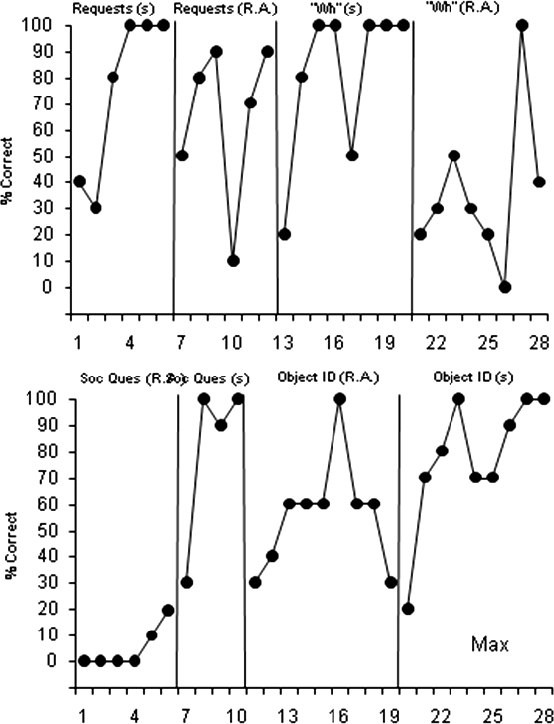

Figure 2.

Percentage of correct verbal responses across shaping (S) and reasonable attempts (RA) conditions for Max.

Figure 3.

Percentage of correct verbal responses across shaping (S) and reasonable attempts (RA) conditions for Al.

Only Al reached mastery during the reasonable attempts condition (see reciprocal conversation). To achieve mastery, however, the phase had to be extended beyond the yoking procedure for two additional sessions. Although Al's performance was better than that of James and Max in the reasonable attempts conditions, he did not achieve mastery in any other phase of the reasonable attempts condition. In contrast, he failed to achieve mastery in the allotted number of sessions in only one shaping phase (social questions).

James's and Max's data show that neither student achieved mastery in any reasonable attempts condition, although they never failed to do so in any shaping phase. James did make noticeable progress with fill ins, and Max's requesting, question answering, and object identification improved. However, neither participant achieved mastery during the reasonable attempts conditions.

DISCUSSION

Students in the current study acquired vocal responses more rapidly when shaping was used as opposed to reinforcing reasonable attempts. Such a result could be predicted from the shaping literature and supports the use of shaping methodologies when teaching language to children with autism spectrum disorders. These data do not support those collected by prior investigators. Differences may be the result of differing procedures (i.e., conducting a greater number of sessions, using intelligibility as a criterion for reinforcement rather than examining phonetic targets, using a more stringent mastery criterion, working on a wider variety of vocal responses).

Part of this discrepancy may lie with the definition of reasonable attempts. As characterized by Schreibman et al. (1996), “reinforcers are contingent upon attempts that may not be completely correct and may not be quite as good as previous attempts, but within the broader range of correct responses” (p. 356). This broader range of correct responses requires that the attempt “be ‘reasonable’ in terms of being directed at the interventionist or training materials and being within the broader class of correct responses” (p. 356). This definition, however, may lead to some confusion and difficulty in standardizing procedures. Consider the example Schreibman et al. provide: “Thus, a child who has demonstrated the ability to say ‘ball’ clearly will not receive reinforcement for a muffled ‘ba’ sound on a later occasion because it is not a reasonable attempt” (pp. 356–357). This example seems in conflict with the definition the authors provided in terms of the response not having to be “as good” as prior responses. This failure to reinforce is presumably due to the response not being directed at the interventionist or not being within the broader definition of correct responses, but this would also be consistent with shaping.

Let us consider a second example (Schreibman et al., p. 357). On one occasion, a student was asked whether she would like to play with a toy elephant or toy bear. The child tried to grab the elephant, and the interventionist placed the toy out of the child's reach and repeated the question. Following the child's verbalization of “ell-ee,” the child was given the toy. This is cited as an example of reinforcing the reasonable attempt. We could argue, however, that this is also an example of shaping, unless we have previously established that the child has previously emitted a closer approximation to “elephant.” Such background information, unfortunately, is not provided. We can only deduce that silent grabbing was not reinforced. Again, this is consistent with a shaping approach.

Despite these procedural variations, there may be a simple explanation for the differences observed. The children who participated in this study were enrolled in a preschool that emphasized shaping. Students, therefore, were familiar with this particular teaching procedure, and the ambiguity of the reasonable attempts condition may have been so unfamiliar that it caused the resulting dramatic differences. In other words, reinforcement provided during the reasonable attempts conditions appeared to confuse the students. On one occasion, for example, 1 student responded “good trying” to a question prompt after receiving reinforcement for a reasonable attempt. This was novel phrasing not used in the study, and suggested that the student was equating the reasonable attempts condition with earlier shaping experiences. Anecdotally, other observations seemed to confirm this. The speech therapist who conducted some of the sessions noted that pronoun reversal was more pronounced for 1 student during reasonable attempts conditions. A 2nd student's perseverative behavior increased during reasonable attempts conditions as well as immediately following these sessions.

L. K. Koegel, Koegel, and Dunlap (1996) propose “learned helplessness” as a possible reason why students in their study did not perform as well in the shaping condition. It is possible that in the current study, we might have seen the opposite effect. Students included in our study may have been feeling “helpless” insofar as they did not know what was expected in the reasonable attempts condition. Replicating these procedures with completely naive students may clear up these difficulties.

Perhaps for some students who are particularly averse to the DTT arrangement, reinforcing reasonable attempts would be less aversive and therefore a more effective teaching strategy. In this direction, it should be noted that the current study was begun during the second half of the school year, when staff had been established as reinforcers. Any competing or noncompliant behaviors had been previously extinguished, and students worked well and showed no signs of unpleasant affect.

Interestingly, for the current participants, the shaping condition seemed to be more motivating. Another reason for this may be that reinforcement delivered on a more intermittent schedule slowed the decrease in reinforcer effectiveness that occurs due to satiation. As is so often the case in applied behavior analysis, the question is not “Which system works best?” but rather “Which system works best, for which students, under what conditions?” We would likely not start with strict shaping procedures for students who are just beginning a program for fear of rendering teaching sessions aversive. Early on in intervention, when the push must be on making sessions and staff reinforcing, the reinforcement of reasonable attempts may be an excellent strategy.

Future research will have to address issues of interobserver agreement and treatment integrity for reasonable attempts conditions. By their very nature, it is difficult to state with precision exactly what responses meet criteria for reinforcement.

Contributor Information

Bobby Newman, Room to Grow.

Dana Reinecke, Room to Grow.

Marissa Ramos, Room to Grow.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.) Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S.R, Taras M, O'Malley-Cannon B. Teaching new skills to young children with autism. In: Maurice C, Green G, Luce S.C, editors. Behavioral intervention for young children with autism. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1996. pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleece L, Gross A, O'Brien T, Kistner J, Rothblum E, Drabman R. Elevation of voice volume in young developmentally delayed children via an operant shaping procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:351–355. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel L.K, Koegel R.L, Dunlap G, editors. Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community. Toronto: Brookes; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel R.L, O'Dell M, Dunlap G. Producing speech use in nonverbal autistic children by reinforcing attempts. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 1988;18:525–538. doi: 10.1007/BF02211871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf R, McEachin J. A work in progress: Behavior management strategies and a curriculum for intensive behavioral treatment of autism. New York: DRL Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas O.I. The autistic child: Language development through behavior modification. New York: Irvington; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport M.F. Notes from the speech pathologist's office. In: Maurice C, Green G, Foxx R.M, editors. Making a difference: Behavioral intervention for autism. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2001. pp. 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Romanczyk R.G, Lockshin S, Matey L. Individualized goal selection curriculum. Apalachin, NY: Clinical Behavior Therapy Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L, Stahmer A.C, Pierce K.L. Alternative applications of pivotal response training. In: Koegel L.K, Koegel R.L, Dunlap G, editors. Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community. Toronto: Brookes; 1996. pp. 353–371. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M.L, Partington J.W. Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Pleasant Hill, CA: Behavior Analysts, Inc; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]