Sirs: In 1996, a new variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) linked to the cattle bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) epidemic was described in the United Kingdom (UK) [8, 2]. Up until now, 191 cases have been reported worldwide. Most of these cases have occurred in the UK (159), but in recent years vCJD has been identified in a number European countries with indigenous outbreaks of BSE, including 18 cases in France, four in Ireland, two in the Netherlands and single cases in Portugal, Italy and Spain. However, a growing number of cases of vCJD have also been identified in countries outside Europe including Japan (n = 1), the United States (n = 2) and Canada (n = 1) and also in Saudi Arabia (n = 1), in which BSE has not been identified. A number of the non-UK cases, including two Irish, the Canadian, the two US cases, and possibly the Japanese case, may well have been infected during periods of residence in the UK, but the majority of cases (n = 25) occurring outside the UK, like the two cases that developed in the Netherlands, had never visited the UK [1]. In this study we describe the first patient identified with vCJD in the Netherlands [3].

The patient was a 26-year-old woman with previous medical history of two abortions in 1996 and in 1998 and a psychiatric history of anxiety and a phobic disorder since 1999. However, one year previous to the vCJD disease onset, she had completely recovered from her psychiatric problems and was able to function normally. She worked in a catering and food-processing business for 6 years, from 1998 to the disease onset. She consumed all types of meat frequently, including raw meat, and particularly processed meat products. She had no history of neurosurgical procedures, hormonal treatments, or tissue or organ grafts, and she had never received or donated blood. She never traveled to the UK. She had no family history of dementia or any other neurodegenerative disorder.

From November 2003, the patient developed new psychiatric symptoms, particularly anxiety and aggressive behavior. In spring 2004, the family also noticed some forgetfulness. A few months later, the psychiatric symptoms worsened. She suffered from panic attacks, became very dependent and apathetic, and showed regressive behavior. She also had visual hallucinations in which she saw animals. In July 2004, two weeks after a dental extraction, she started complaining of severe facial pain in her upper jaw. Her dentist examined her but no organic cause was found. At that point she was seen by a psychiatrist who suspected that she was suffering from anxiety and a conversion disorder.

In September 2004, the patient developed involuntary movements of her right foot, with dystonic eversion-inversion posturing and occasionally some jerking movements. She also developed paresthesiae in the lower limbs and gait difficulties, especially when walking in the dark. In November, the family also noticed dysarthria and problems in the motor coordination of the upper limbs. She had several episodes of blurring of vision. During this period, she was twice hospitalized in a psychiatric ward because of increasing anxiety, regressive behavior and facial pain.

From January to March 2005 the involuntary movements worsened significantly, accompanied by generalized stiffness, now involving all extremities. In March the patient was again hospitalized in a psychiatric ward with the clinical diagnosis of a conversion disorder, and treatment with Haloperidol was started. Two days later she suffered a tonic-clonic seizure followed by hyperthermia that required admission to an intensive care department. No cause was found for the persistent high temperature, and the neuroleptic medication was withdrawn. The patient was treated for malignant neuroleptic syndrome without success. The neurological state of the patient worsened rapidly.

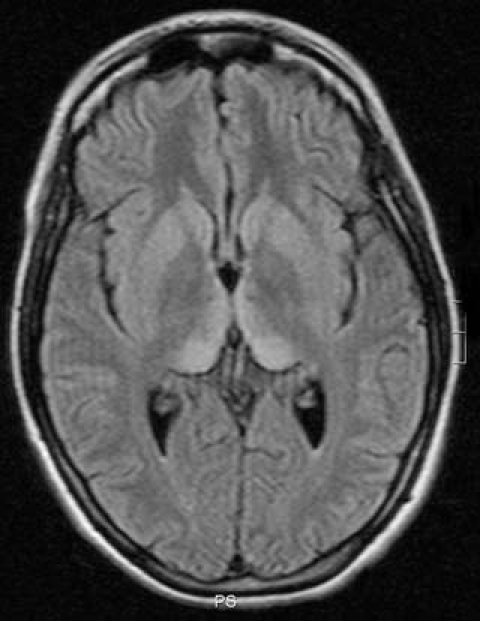

On neurological examination she was mute, opened her eyes to verbal stimuli but there was no visual fixation. She had variable extrapyramidal rigidity in the extremities with dystonic movements of the hands and feet, and she had a positive Babinski sign in her right foot. Routine laboratory examinations only revealed mild increases of the aspartate aminotranspherase (ASAT) and creatine phosphokinase (CPK), which later normalized. The cerebrospinal fluid was normal, and 14-3-3 protein was not detectable. Tau protein determination in CSF was performed after the referral of the patient to the CJD registry, and it showed abnormally high levels (1314 ng/l). The electroencephalogram showed generalized slowing, more evident in the left hemisphere, but without any periodic complexes. Brain MRI showed symmetrical hyperintensities in the pulvinar and the dorsomedial nuclei of the thalami on T2- and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)-weighted images (Figure 1). Genotyping of the prion protein gene (PRNP) identified no mutation and homozygosity for methionine at codon 129.

Fig. 1.

FLAIR-weighted images of the brain MRI study, showing bilateral symmetrical regions of hyperintensity in the pulvinar and the dorsomedial nuclei of the thalami (“hockey stick sign”)

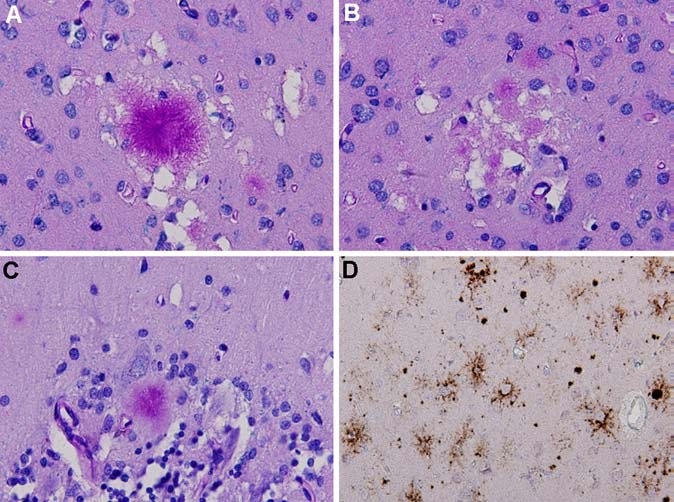

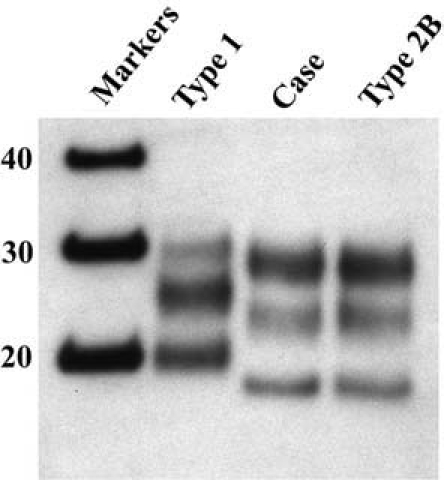

Following the current WHO criteria, the patient was diagnosed in life with probable vCJD based on the clinical features, laboratory findings, brain MRI findings and PRNP genotyping [7]. In May 2005 the patient died, and the diagnosis was confirmed by post mortem neuropathological examination of the brain, which showed typical features of vCJD, including florid plaques (Figure 2). Western blot analysis of unfixed brain tissue showed a characteristic type 2B PrPSc isoform (Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

Neuropathology of variant CJD: A. florid plaque surrounded by small areas of spongiform change in the occipital cortex (Luxol-PAS stain). B. Multiple small cluster plaques in the occipital cortex (Luxol-PAS stain). C. kuru-type plaque in the cerebellar cortex (Luxol-PAS stain). D. Immunohistochemistry for prion protein (using monoclonal antibody 3F4) shows strong staining of plaques in the occipital cortex, along with amorphous and pericellular deposits

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of protease-resistant prion protein in this patient (Case) shows an identical pattern of glycosylation and size of the unglycosylated fragment (lowest band ∼19Kd) to a control case of vCJD (Type 2B), which is markedly different from a case of sporadic CJD (Type 1). (Reproduced with permission of Prof. Dr. A.J.P.M. Overbeke editor of Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd [3])

Non-UK cases of vCJD may potentially have been infected during a period of residence in the UK in the 1980s and early 1990s (for example the US and Canadian cases). Our patient had never traveled to the UK, but may have been exposed through either indigenous BSE infected animals or BSE infected exports from the UK to the Netherlands during the 1980s and early 1990s. Thus far, all non-UK cases of vCJD who had never previously visited the UK show disease characteristics analogous to the UK cases. The clinical features, PRNP codon 129 genotype, neuropathological findings and western blot PrPSc isoform of our patient are indistinguishable from the United Kingdom vCJD cases, pointing towards a common etiological agent.

The Netherlands CJD surveillance system is part the EUROCJD group, a EU-funded network established in 1993 with the aim of monitoring the disease incidence and detecting new vCJD cases [5]. In the Netherlands, only 80 BSE cases have been reported [4]. The first case of variant CJD diagnosed in the Netherlands highlights the importance of continuing multinational surveillance of human prion diseases, even in countries with a low BSE incidence, during the preparation of this manuscript a second probable vCJD case has been ascertained in our country [6].

The early detection of vCJD patients is crucial as there are major public health implications, including of tracing of blood products from patients who were blood donors and tracing of surgical instruments, in this case dental instruments. Despite of a long disease course (18 months) the diagnosis in this patient was particularly difficult owing to the past psychiatric history. The brain MRI findings played a crucial role in the diagnosis by the treating neurologist (J.I.H.). This triggered the notification to the CJD registry in Rotterdam.

This case report underscores the value of the MRI in the diagnosis of vCJD and the need for an increased awareness of radiologists and neurologists of the MRI findings in vCJD, including in countries with a low incidence of BSE.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the relatives of the patient for their kind collaboration in collecting the clinical data. We thank Mark Head for performing the western blot analysis and providing figure 3. We thank Matthew Bishop and Alejandro Arias for performing the genetic analysis. We thank Prof. Berciano for his help in the edition of the figures. The national CJD surveillance is supported in the Netherlands by the Dutch Ministry of Health Welfare and Sports. Pascual Sanchez-Juan was supported by the postMIR grant Wenceslao Lopez Albo from the IFIMAV Institute of the Fundación Pública Marqués de Valdecilla.

References

- 1.The European and Allied Countries Collaborative Study Group of CJD (EUROCJD) plus the Extended European Collaborative study Group of CJD (NEUROCJD) web page. http://www. eurocjd.ed.ac.uk (consulted July 2006)

- 2.Hill AF, Desbruslais M, Joiner S, Sidle KC, Gowland I, Collinge J, Doey LJ, Lantos P (1997) The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature 389:448–526 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jansen C, Houben MPWA, Hoff JI, Sanchez- Juan P, Spliet WGM, Rozemuller AJM, van Duijn CM (2005) Eerste patie nte in Nederland met de nieuwe variant van de ziekte van Creutzfeldt-Jakob. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 149:2949–2954 [PubMed]

- 4.National cattleman’s beef association. New variant CJD (nvCJD). http:// www.bseinfo.org/resoCases.aspx (consulted July 2006)

- 5.Pocchiari M, Puopolo M, Croes EA, Budka H, Gelpi E, Collins S, Lewis V, Sutcliffe T, Guilivi A, Delasnerie-Laupretre N, Brandel JP, Alperovitch A, Zerr I, Poser S, Kretzschmar HA, Ladogana A, Rietvald I, Mitrova E, Martinez-Martin P, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Glatzel M, Aguzzi A, Cooper S, Mackenzie J, van Duijn CM, Will RG (2004) Predictors of survival in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and other human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Brain 127:2348–2359 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Van Duijn C, Ruijs H (2006) Timen Second probable case of vCJD in the Netherlands. A Euro Surveill 11:E060629.4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.WHO (1998) Human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Weekly Epidemiological Record 47:361–365 [PubMed]

- 8.Will RG, Ironside JW, Zeidler M, Cousens SN, Estibeiro K, Alperovitch A, Poser S, Pocchiari M, Hofman A, Smith PG. (1996) A new variant of Creutzfeldt- Jakob disease in the UK. Lancet 347:921 [DOI] [PubMed]