Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) fulfils vital signalling roles in an array of cellular processes, yet until recently it has not been possible selectively to visualize real-time changes in PIP2 levels within living cells. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labelled Tubby protein (GFP-Tubby) enriches to the plasma membrane at rest and translocates to the cytosol following activation of endogenous Gαq/11-coupled muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in both SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells and primary rat hippocampal neurons. GFP-Tubby translocation is independent of changes in cytosolic inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and instead reports dynamic changes in levels of plasma membrane PIP2. In contrast, enhanced GFP (eGFP)-tagged pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C (PLCδ1) (eGFP-PH) translocation reports increases in cytosolic inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Comparison of GFP-Tubby, eGFP-PH and the eGFP-tagged C12 domain of protein kinase C-γ [eGFP-C1(2); to detect diacylglycerol] allowed a selective and comprehensive analysis of PLC-initiated signalling in living cells. Manipulating intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in the nanomolar range established that GFP-Tubby responses to a muscarinic agonist were sensitive to intracellular Ca2+ up to 100–200 nM in SH-SY5Y cells, demonstrating the exquisite sensitivity of agonist-mediated PLC activity within the range of physiological resting Ca2+ concentrations. We have also exploited GFP-Tubby selectively to visualize, for the first time, real-time changes in PIP2 in hippocampal neurons.

Keywords: phospholipase C; phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; Tubby protein; SH-SY5Y; hippocampal neuron

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is the primary substrate for cellular phospholipase C (PLC) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) activities, generating the second messengers inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate respectively (Berridge 1993; Toker and Cantley 1997). As well as being a key substrate for second messenger-generating enzymes and providing a target for the membrane-association of a variety of protein domains, PIP2 is also an important signalling molecule in its own right and is implicated in membrane trafficking, actin cytoskeleton remodelling and the regulation of ion channels and transporters (Cremona and De Camilli 2001; McLaughlin and Murray 2005; Suh and Hille 2005; Ling et al. 2006). For example, in the CNS a number of Gαq/11-coupled receptors modulate membrane excitability by inhibiting the KCNQ2/3 current (see Delmas and Brown 2005) via distinct receptor-dependent mechanisms. Angiotensin and muscarinic acetylcholine (mACh) receptors inhibit KCNQ2/3 channels by depleting PIP2 (Suh and Hille 2002; Zaika et al. 2006), whereas activation of Gαq/11-coupled bradykinin and ATP receptors suppress current through IP3- and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent, PIP2-independent mechanisms (Gamper and Shapiro 2003; Zaika et al. 2007). As both the substrate and products of PLC can independently influence neuronal activity via distinct mechanisms, the ability selectively to visualize real-time changes in PIP2, IP3 and DAG is highly desirable for the further study of PLC signalling in vivo.

The development of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-labelled pleckstrin homology domain of PLCδ1 (eGFP-PH; Stauffer et al. 1998; Varnai and Balla 1998) has provided a means of visualizing real-time changes in PLC activity, by exploiting the high affinity and selectivity of this eGFP-PH domain for PIP2 (Hirose et al. 1999). The eGFP-PH probe enriches to the plasma membrane and on activation of PLC, translocates to the cytosol (Stauffer et al. 1998; Varnai and Balla 1998). The relative causal contributions of PIP2 depletion at the plasma membrane and elevation of IP3 in the cytoplasm to eGFP-PH translocation have been widely debated (see Varnai and Balla 2006). A number of studies have suggested a predominant role for changes in PIP2 in the dynamics of eGFP-PH translocation (Varnai and Balla 1998; van der Wal et al. 2001; Winks et al. 2005), however, the eGFP-PH domain of PLCδ1 exhibits (at least in vitro) a higher affinity for IP3 than for PIP2 (Hirose et al. 1999), and theoretical (Xu et al. 2003) and empirical evidence (Hirose et al. 1999; Okubo et al. 2001; Nash et al. 2002, 2004) has accrued indicating that eGFP-PH translocation in live cells may primarily reflect changes in cytosolic IP3. Clearly, these data indicate that eGFP-PH does not represent a truly selective tool for the study of dynamic changes in PIP2 levels in cells and a more PIP2-selective biosensor is needed.

The observation that Tubby protein is localized to the plasma membrane via a novel PIP2-binding domain (Santagata et al. 2001) raises the possibility that this might be an alternative candidate for a PIP2 biosensor. A GFP-labelled version of the full-length Tubby protein was found to enrich to the plasma membrane when recombinantly expressed in a variety of cell backgrounds (Santagata et al. 2001). Intriguingly, on activation of Gαq/11-coupled receptors GFP-Tubby rapidly translocated from membrane to cytosol and ultimately (within 2 h) to the nucleus, where it has been proposed to act as a transcriptional regulator (Boggon et al. 1999; Santagata et al. 2001). Recent reports describe the use of a fluorescently labelled, modified form of the C-terminal domain (amino acids 248–505) of Tubby [R332H-Tubby (248–505)-yellow fluorescent protein] to visualize changes in PIP2 levels in human embryonic kidney 293 cells (Quinn et al. 2008) and to assess bradykinin-stimulated PIP2 synthesis in sympathetic neurons (Hughes et al. 2007), suggesting that probes based on the Tubby protein might provide specific biosensors for PIP2.

Therefore, we set out to investigate further the acute translocation of (full-length) GFP-Tubby on Gαq/11-coupled receptor activation to establish whether this can be utilized as an index of real-time changes in plasma membrane PIP2 levels in live cells. Initially, we investigated the translocation of GFP-Tubby, in comparison with eGFP-PH and the established biosensor for DAG [eGFP-C1(2); Oancea et al. 1998] in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. We have extensive quantitative knowledge of phosphoinositide turnover in these cells from earlier studies from our laboratory (e.g. Willars et al. 1998), making them an ideal model system in which to assess a potential PIP2 biosensor. We have established that GFP-Tubby translocation on PLC activation reflects dynamic changes in plasma membrane PIP2, in both neuroblastoma cells and cultured rat hippocampal neurons. In contrast, the translocation of eGFP-PH predominantly reports changes in cytosolic IP3, at least in the cell systems investigated in this study. GFP-Tubby is therefore a potential real-time fluorescent biosensor, suitable for the visualization of changes in PIP2 levels in live cells and we have used it here to evaluate the Ca2+-sensitivity of agonist-mediated PLC activity in SH-SY5Y cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Cell culture supplies and lipofection reagents were obtained from Invitrogen (Paisley, UK). Thermolysin, pronase, Dnase I, poly-d-lysine, cytosine arabinoside and methacholine (MCh) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK). Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK) supplied wortmannin (Wort) and LY294002, while Fluo-4 AM and Fura-Red-AM were obtained from Molecular Probes (Leiden, The Netherlands).

Neuroblastoma cell culture and transfections

SH-SY5Y cells were maintained in minimum essential medium supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B, 2 mM l-glutamine and 10% newborn calf serum. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of O2/CO2 (19 : 1) and were routinely split 1 : 5 every 3–4 days, using trypsin–EDTA. For experiments, cells were seeded onto 25 mm glass coverslips for 24 h prior to transient transfection (where appropriate) with 0.5 μg of eGFP-PH, full-length GFP-Tubby or eGFP-C1(2) plasmid DNA, using Lipofectamine2000 (1 : 3 ratio). For co-expression experiments, cells were transfected as above, but with 1.0 μg of dsRed-IP3 3-kinase plasmid DNA in addition to 0.5 μg of GFP-labelled biosensor plasmid DNA. Experiments were performed 24–48 h post-transfection.

Hippocampal neuron culture and transfection

Hippocampal neurons were prepared from 1-day-old Lister Hooded rats as described previously (Nash et al. 2004; Willets et al. 2004). Briefly, isolated hippocampi were chopped and treated with pronase E (0.5 mg/mL) and thermolysin (0.5 mg/mL) in a HEPES-buffered salt solution [Hank’s balanced salt solution (in mM): NaCl 130, HEPES 10, KCl 5.4, MgSO4 1.0, glucose 25 and CaCl2 1.8, pH 7.2) for 30 min. The tissue was re-suspended in Hank’s balanced salt solution supplemented with 40 μg/mL Dnase I and triturated through a fire-polished glass pipette. Following centrifugation (400 g, 3 min) and further trituration, cells were re-suspended in Neurobasal medium containing B27 supplement, 10% heat-inactivated foetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), l-glutamine (0.5 mM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM) and l-serine (1 mM) and plated onto poly-d-lysine-coated 25 mm glass coverslips. After 24 h, cytosine arabinoside (5 μM) was added to inhibit glial cell proliferation and a further 48 h later, cells were transferred to serum-free Neurobasal medium. Cells were transfected after 11 days in vitro (DIV) using Lipofectamine2000, as described above. Neurons were routinely imaged at 12–15 DIV.

Calcium imaging

Cells were loaded with Fluo-4 AM (2 μM, 40–60 min) before mounting on the stage of an Olympus IX70 inverted epifluorescence microscope. Cells were incubated at 37°C using a temperature controller and microincubator (PDMI-2 and TC202A; Burleigh, Harpenden, UK) and were continuously perfused with Krebs–Henseleit buffer (composition in mM: NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 1.3, KH2PO4 1.2, MgSO4 1.2, Na HCO3 25, HEPES 5 and glucose 10). Cells were imaged at a rate of 1–2 Hz using an Olympus FV500 confocal microscope (Olympus Europa, Hamburg, Germany) fitted with a 60× oil immersion objective lens. Fluo-4 was excited using the 488 nm line of an argon ion laser, and emissions over 505 nm were collected. Increases in intracellular Ca2+ were defined as F/F0 where F was the fluorescence at any given time, and F0 was the initial basal level of Ca2+.

Confocal imaging of fluorescent biosensors

Cells expressing GFP-labelled biosensors [eGFP-PH, GFP-Tubby and eGFP-C1(2)] were imaged using an Olympus FV500 laser scanning confocal IX70 inverted microscope and continuously perfused with Krebs–Henseleit buffer at 37°C. Cells were excited via the 488 nm line of the argon laser and GFP emissions were collected at 505–560 nm. Increases in signal were calculated as the F/F0 increase in cytosolic GFP levels. In co-imaging experiments, GFP and dsRed were sequentially excited via the 488 nm line of the argon laser and a 543 nm helium–neon laser respectively. GFP and dsRed emissions were collected at 505–560 and > 660 nm respectively. In experiments requiring the co-imaging of Ca2+ and GFP-labelled biosensors, transfected cells were loaded with Fura-Red (3 μM, 1 h) and excited by the 488 nm line of an argon ion laser. Emissions from GFP-labelled biosensors and Fura-Red were collected at 505–560 and > 660 nm respectively.

Data analysis and statistics

Data were analysed using graphpad Prism 4.0 (San Diego, CA, USA). Data were presented throughout as mean ± SEM from three or more coverslips and statistical comparisons were made using Student’s unpaired t-test or one way anova followed by Bonferroni’s or Dunnett’s post-test (statistical significance is indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01 or ***p<0.001, throughout).

Results

Expressing GFP-Tubby, eGFP-PH and eGFP-C1(2) in SH-SY5Y cells

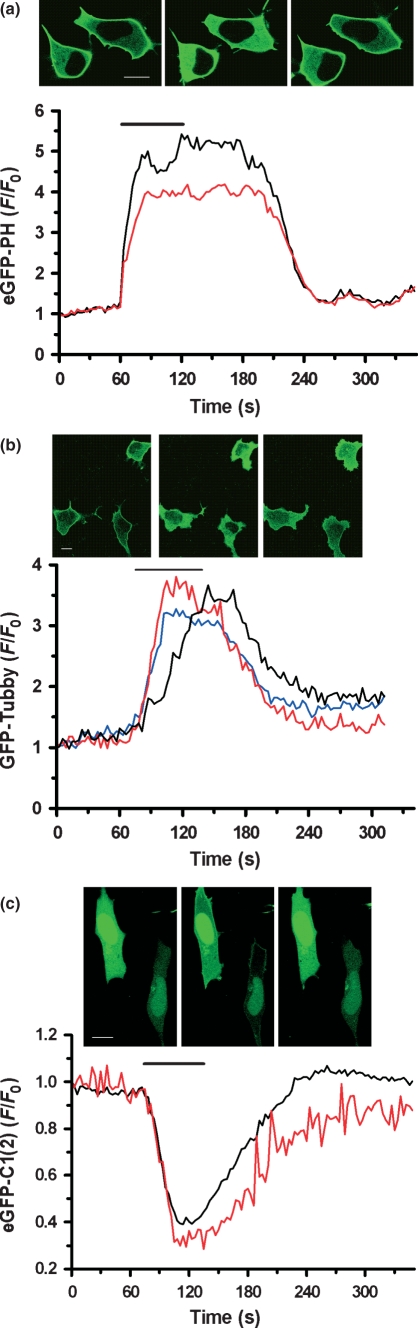

To investigate the potential of the GFP-Tubby construct to act as a single cell fluorescent biosensor for PIP2, we transiently expressed GFP-Tubby (Fig. 1b) [and for comparison, eGFP-PH (Fig. 1a) and eGFP-C1(2) (Fig. 1c)] in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Under basal conditions, eGFP-PH predominantly localized to the plasma membrane, with a lower level of fluorescence in the cytoplasm, as has been reported previously in SH-SY5Y cells (Nash et al. 2001). GFP-Tubby exhibited a similar distribution to eGFP-PH, with the exception of a significant nuclear localization of this probe in some cells, as has been observed in other cell-types (Santagata et al. 2001). Consistent with previous reports (Oancea and Meyer 1998; Bartlett et al. 2005) eGFP-C1(2) fluorescence was observed in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments under basal conditions.

Fig. 1.

Translocation of GFP-labelled biosensors in response to mACh receptor activation in SH-SY5Y cells. Representative traces and confocal images of SH-SY5Y cells expressing eGFP-PH (a), GFP-Tubby (b) or eGFP-C1(2) (c) in response to MCh (100 μM; black horizontal bars). Data were expressed as a ratio change in cytosolic fluorescence emission (F) relative to the initial basal fluorescence (F0). Data were represented as (F/F0) − 1 (for eGFP-PH and GFP-Tubby) or 1 − (F/F0) [for eGFP-C1(2)]. Scale bars, 10 μm.

On stimulation of the endogenous M3 mACh receptor population expressed in SH-SY5Y cells (Lambert et al. 1989) with MCh (100 μM), a robust translocation of eGFP-PH and GFP-Tubby from plasma membrane to cytosol was observed (Fig. 1a and b). No obvious change in nuclear localization of GFP-Tubby was observed over the time-course of our experiments (data not shown). Stimulation of SH-SY5Y cells expressing eGFP-C1(2) with MCh (100 μM) elicited a decrease in cytosolic fluorescence (Fig. 1c). Translocation of all three probes to MCh occurred in a concentration-dependent manner, allowing concentration–response curves to be constructed (see Fig. S1) and pEC50 values to be determined (Table S1). Mean pEC50 estimates for MCh-mediated translocation of eGFP-PH (5.19 ± 0.11) and eGFP-C1(2) (4.89 ± 0.23) were not significantly different to one another, but MCh was significantly less potent in translocating GFP-Tubby (pEC50 = 4.53 ± 0.21) than eGFP-PH (p<0.05; Table S1). Comparison of the time-courses of translocation of each probe revealed that eGFP-C1(2) translocated most rapidly, with a mean t10–90 of 31 s, significantly faster than that of eGFP-PH (p<0.05; Table S1). GFP-Tubby translocation occurred substantially slower (p<0.001) than either of the other two probes, with a mean t10–90 of 59 s (Table S1).

One limitation of the use of protein domains with high affinity for inositol phospholipids (such as the PH domain of PLCδ1) is that their over-expression might bind to and thereby preclude hydrolysis (in this case, of PIP2), as has previously been suggested for eGFP-PH (Varnai and Balla 1998). We therefore investigated intracellular Ca2+ release in response to MCh (using Fura-Red as a Ca2+ indicator) in cells expressing each of the GFP-labelled biosensors, compared with untransfected control cells. Ca2+ responses to 1 μM MCh (given as 1 − F/F0 self-ratios) were significantly lower in cells expressing eGFP-PH (0.26 ± 0.02; 20 cells from three coverslips) compared with untransfected control cells (0.32 ± 0.01; 27 cells from three coverslips) (P<0.01). In contrast, neither GFP-Tubby [0.33 ± 0.03 (+ GFP−Tubby) vs. 0.39 ± 0.02 (control)] nor eGFP-C1(2) [0.32 ± 0.02 (+ eGFP−C1(2)) vs. 0.32 ± 0.03 (control)] significantly affected agonist-induced intracellular Ca2+ responses in SH-SY5Y cells. These data indicate that expression of eGFP-PH, but not GFP-Tubby, can attenuate agonist-mediated PLC activity.

The effect of over-expression of dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase on intracellular Ca2+ release and translocation of eGFP-PH, eGFP-C1(2) and GFP-Tubby

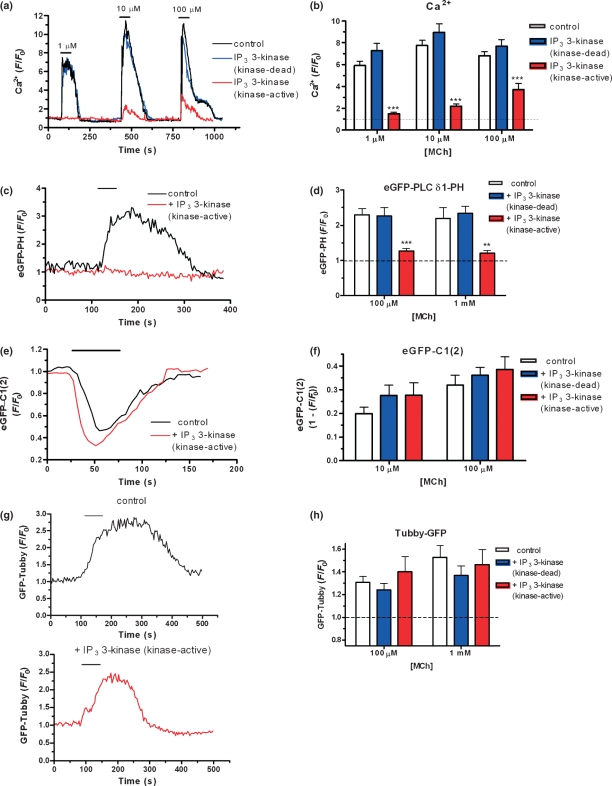

To investigate the role of IP3 production in the translocation of eGFP-PH and GFP-Tubby, we have examined the effect of over-expressing dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase on the translocation profile of each probe, as we have previously performed for eGFP-PH in other cell systems (Nash et al. 2002, 2004). Over-expression of the ‘kinase-active’ dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase significantly reduced the Ca2+ response to 1, 10 and 100 μM MCh, while expression of a ‘kinase-dead’ mutant of dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase had no effect (Fig. 2a and b), indicating an enhanced metabolism of IP3 in the subpopulation of cells over-expressing the ‘kinase-active’ 3-kinase construct.

Fig. 2.

IP3 3-kinase over-expression attenuates Ca2+ and eGFP-PH, but not eGFP-C1(2) or GFP-Tubby, responses to MCh in SH-SY5Y cells. (a) Representative traces illustrating changes in intracellular Ca2+ in SH-SY5Y cells in response to MCh (indicated by black horizontal bars), as measured by increases in the fluorescence of Fluo-4 AM. Data were expressed as a ratio change in cytosolic fluorescence emission (F) relative to the initial basal fluorescence (F0). Data were shown for un-transfected cells (control; black trace), cells expressing dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase (kinase-dead; blue trace), and cells expressing dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase (kinase-active; red trace). (b) Cumulative data showing increases in intracellular Ca2+ in SH-SY5Y cells in response to MCh for untransfected cells (control; open bars), cells expressing dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase (kinase-dead; blue shaded bars), and cells expressing dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase (kinase-active; red shaded bars). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM for 12–104 cells from at least three separate coverslips. Representative traces of eGFP-PH (c), eGFP-C1(2) (e) and GFP-Tubby (g) translocation in response to MCh (100 μM; black horizontal bar) in SH-SY5Y cells expressing biosensor alone (black trace) or co-expressed with dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase (kinase-active) (red trace). Cumulative data representing eGFP-PH (d), eGFP-C1(2) (f) and GFP-Tubby (h) translocation in response to MCh (10 μM–1 mM, as indicated) in SH-SY5Y cells expressing biosensor alone (open bars), or co-expressing biosensor with either dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase (kinase-dead; blue shaded bars), or dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase (kinase-active; red shaded bars). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM for five or more cells from at least three separate coverslips. Differences between cell populations were determined by one-way anova and Dunnett’s post hoc test (**p<0.01; ***p<0.001). Scale bars, 10 μm.

Figure 2c illustrates a representative trace from a pair of SH-SY5Y cells, each expressing eGFP-PH, but only one co-expressing dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase. On addition of MCh (100 μM), the cell expressing eGFP-PH alone exhibited a robust elevation in cytosolic fluorescence (Fig. 2c). In contrast, in the cell co-expressing eGFP-PH and dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase, no response was observed. Similar results were obtained in a number of experiments using both 100 μM and 1 mM MCh, with highly significantly lower responses observed in cells expressing dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase than in cells expressing either eGFP-PH alone or eGFP-PH in combination with the ‘kinase-dead’ 3-kinase construct (summarized in Fig. 2d). In contrast, co-expression of dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase with eGFP-C1(2) had no influence on the translocation of the DAG sensor to either 10 or 100 μM MCh (Fig. 2a and b), suggesting that the loss of Ca2+-mediated positive feedback on to PLC does not account for the reduced translocation of eGFP-PH on co-expression of dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase. These data therefore suggest that in SH-SY5Y cells, eGFP-PH translocation in response to mACh receptor stimulation is largely dependent on IP3 generation. In addition, GFP-Tubby responses to MCh (100 μM or 1 mM) were similar in SH-SY5Y cells regardless of whether the probe was expressed alone or co-expressed with either ‘kinase-active’ or ‘kinase-dead’ dsRed2-IP3 3-kinase (Fig. 2c and d). Translocation of GFP-Tubby in response to mACh receptor stimulation therefore does not reflect dynamic changes in cytosolic IP3.

GFP-Tubby translocation reports dynamic changes in PIP2

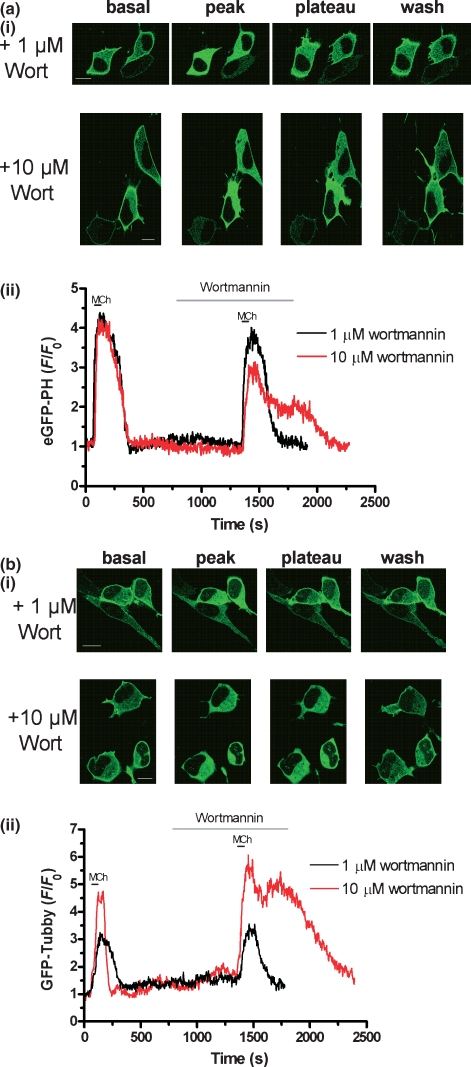

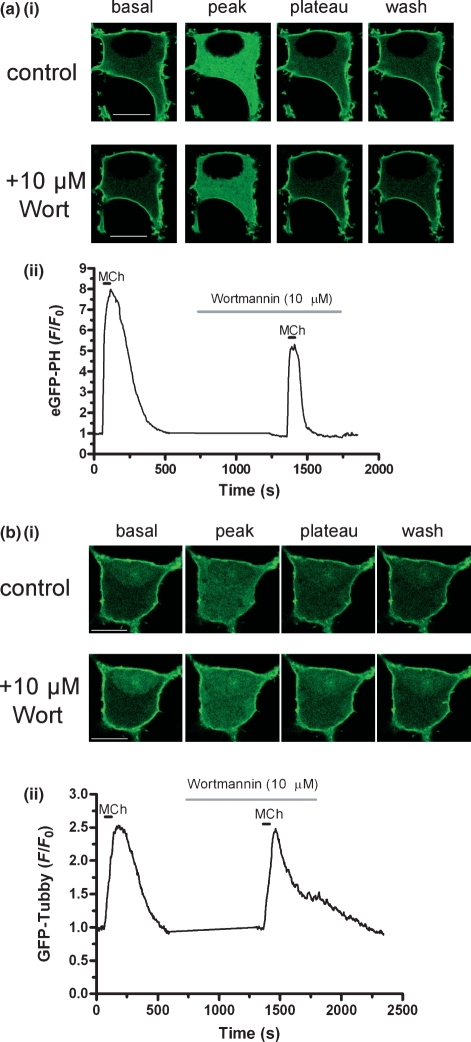

To investigate the extent to which eGFP-PH and GFP-Tubby translocation in response to MCh in SH-SY5Y cells depends on dynamic changes in plasma membrane PIP2, we investigated the effect of PI4-kinase inhibition on the temporal profile of translocation of these probes. Cells were stimulated initially with MCh (1 mM) alone and then again following incubation with Wort, either at 1 μM (which should fully inhibit PI3-kinase activity, but not PI4-kinases; Balla 2001), or 10 μM (a concentration known to inhibit both PI3- and 4-kinase activities; Nakanishi et al. 1995; Willars et al. 1998). Wort treatment alone had no significant effect on either eGFP-PH or GFP-Tubby localization (data not shown), but peak eGFP-PH responses in the presence of 10 μM (but not 1 μM) Wort were significantly lower (by ∼22%) than in cells not exposed to Wort (Fig. S3a and Table S2), consistent with an attenuated IP3 response in the presence of Wort (Willars et al. 1998). The most striking difference was that in the presence of 10 μM (but not 1 μM) Wort, the eGFP-PH response to 1 mM MCh was maintained at a plateau level (44 ± 6% of peak response remaining 240 s after peak) for as long as Wort was perfused on to the cells (Fig. 3a and Table S2). On washout of Wort the response fully returned to baseline levels [Fig. 3a(ii)], suggesting that PI4-kinase activity is necessary for complete re-association of eGFP-PH with the plasma membrane, consistent with its membrane localization being because of an interaction with PIP2.

Fig. 3.

The effect of PI4-kinase inhibition on translocation of GFP-labelled biosensors in response to MCh in SH-SY5Y cells. Representative images (i) and traces (ii) of eGFP-PH (a) and GFP-Tubby (b) translocation in response to MCh (1 mM; black horizontal bar) in cells in the presence of pre-incubated 1 μM (black trace) or 10 μM (red trace) wortmannin (as indicated by grey horizontal bar). Data were expressed as a ratio change in cytosolic fluorescence emission (F) relative to the initial basal fluorescence (F0) and are representative of at least eight cells from three or more coverslips. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Similar experiments were performed on SH-SY5Y cells expressing GFP-Tubby (Fig. 3b). Pre-incubation with 1 μM Wort had no effect on GFP-Tubby translocation in response to MCh (1 mM). However, in the presence of 10 μM Wort, peak GFP-Tubby responses were significantly enhanced (by ∼66%) in comparison with the same cells prior to Wort treatment (Fig. S3b and Table S2). Similar to eGFP-PH, GFP-Tubby responses to MCh were maintained at a plateau level in the presence of 10 μM (but not 1 μM) Wort, until washout of Wort when the response returned to baseline levels (Fig. S3b and Table S2). However, a more substantial proportion of the peak GFP-Tubby response was maintained in the presence of 10 μM Wort (79 ± 6% of peak response remaining 240 s after peak), suggesting that PI4-kinase activity is essential for the re-localization of GFP-Tubby to the plasma membrane. These data therefore suggest that PIP2 re-synthesis is essential for the re-association of GFP-Tubby with the plasma membrane.

Similar data were obtained using the PI kinase inhibitor LY294002, which at high concentrations has been reported to inhibit PI4-kinase activity (Downing et al. 1996; Willars et al. 1998). These data are summarized in Table S2. Overall, LY294002 had qualitatively similar effects on eGFP-PH and GFP-Tubby translocation in response to MCh as 10 μM Wort, providing strong support for the notion that the activity of PI4-kinases is essential for the re-localization of GFP-Tubby and (to a lesser extent) eGFP-PH following agonist removal.

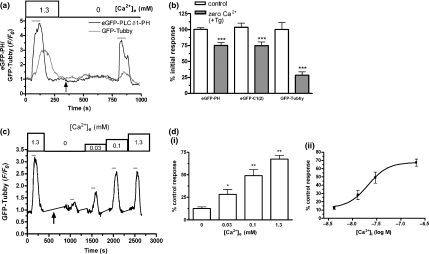

GFP-tagged biosensors can be used to determine the Ca2+-dependency of PLC activation by Gαq/11-coupled receptors

To investigate the Ca2+-dependence of MCh-stimulated PLC activity in SH-SY5Y cells, we examined the effects of manipulating intracellular Ca2+ levels on the magnitude of translocations of eGFP-PH, eGFP-C1(2) and GFP-Tubby in response to MCh. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ and depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin (5 μM) completely abolished Ca2+ responses, measured using Fluo-4 AM, to MCh (100 μM) (data not shown). MCh-mediated GFP-Tubby translocation was substantially reduced under Ca2+-depletion conditions, while eGFP-PH translocation in response to MCh was significantly, but much less markedly attenuated (Fig. 4a). Across a number of experiments, similar profiles were observed with both eGFP-PH and eGFP-C1(2), where depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ attenuated the response observed with both probes by ∼25% (Fig 4b). In contrast, under similar conditions the magnitude of GFP-Tubby translocation in response to MCh (100 μM) was reduced by around 70% (Fig. 4b). The greater sensitivity of GFP-Tubby translocation to Ca2+ availability was exploited in experiments to assess the concentration range over which M3 mACh receptor-stimulated PLC activity is sensitive to [Ca2+]i. Following an initial control response to MCh (100 μM), cells were perfused with Ca2+-free buffer and treated with thapsigargin (5 μM) to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores. A second MCh, response was obtained and on washout, extracellular [Ca2+] was subsequently raised to 0.03, 0.1 and finally 1.3 mM, with further responses to MCh (100 μM) assessed by GFP-Tubby translocation under each condition (Fig. 4c). Raising [Ca2+]e from 0 to just 0.03 mM was sufficient significantly to enhance the GFP-Tubby response to MCh, while approximately two-thirds of the response was recovered in the presence of 1.3 mM [Ca2+]e (Fig. 4d). Thapsigargin treatment and subsequent changes in [Ca2+]e alone had no direct effect on GFP-Tubby localization.

Fig. 4.

Determining the Ca2+-sensitivity of PLC activity using GFP-labelled biosensors. (a) Representative traces demonstrating eGFP-PH (black line) and GFP-Tubby (grey line) responses to MCh (100 μM; grey horizontal bars) in SH-SY5Y cells in Krebs–Henseleit buffer (KHB) containing 1.3 mM Ca2+, and under Ca2+-free (0 Ca2+) conditions and addition of thapsigargin (5 μM; black arrow) to deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores. Data were expressed as a ratio change in cytosolic fluorescence emission (F) relative to the initial basal fluorescence (F0). (b) Cumulative data representing eGFP-PH, GFP-Tubby and eGFP-C1(2) translocation in response to MCh (100 μM) in KHB containing 1.3 mM Ca2+ (control) and in nominally Ca2+-free following the addition of thapsigargin (5 μM) (0 Ca2+ + Tg). Data were presented as a mean percent of an initial control response achieved in the presence of 1.3 mM Ca2+. Differences between control and Ca2+-free responses were determined by one way anova and Bonferroni’s post hoc test (***p<0.001). (c) Representative trace illustrating GFP-Tubby responses to MCh (100 μM; grey horizontal bars) in SH-SY5Y cells in KHB containing 1.3 mM Ca2+ and in 0 (nominally Ca2+-free), 0.03, 0.1 or 1.3 mM Ca2+ following addition of thapsigargin (5 μM; black arrow). Data were expressed as a ratio change in cytosolic fluorescence emission (F) relative to the initial basal fluorescence (F0). [d(i)] Cumulative data representing GFP-Tubby translocation in SH-SY5Y cells following thapsigargin (5 μM) treatment in nominally free extracellular Ca2+ and subsequent stimulation with MCh (100 μM) in the presence of KHB containing 0, 0.03, 0.1 and 1.3 mM Ca2+. Responses were normalized to the initial control response achieved in 1.3 mM Ca2+ prior to thapsigargin treatment and are expressed as mean percent of control response. Differences between responses in nominally Ca2+-free KHB (0 Ca2+) and those in the presence of increasing concentrations of extracellular Ca2+ were determined by one-way anova and Dunnett’s post hoc test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01). [d(ii)] Concentration–response curve representing GFP-Tubby responses to MCh (100 μM) as a function of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (determined from Fluo-4 emissions) after thapsigargin (5 μM) treatment and the establishment of a steady state level of [Ca2+]i. Responses were normalized to the initial control response achieved in 1.3 mM Ca2+ prior to thapsigargin treatment and are expressed as mean percent of this control response. Where appropriate, data were expressed as mean ± SEM for four or more cells from at least three separate coverslips.

To equate the changes in extracellular [Ca2+] with intracellular Ca2+ levels (and therefore the [Ca2+] experienced by PLC), Fluo-4 AM-loaded SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to the protocol described above (without the MCh treatments). A typical trace is shown in Fig. S2. Estimates of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration under these conditions were obtained using the method described by Maravall et al. (2000) for estimating intracellular Ca2+ concentrations from single excitation Ca2+-indicators such as Fluo-4. Mean resting [Ca2+]i levels in SH-SY5Y cells were ∼53 nM, while following treatment with thapsigargin in the presence of Ca2+-free buffer, intracellular Ca2+ levels fell to as low as 4 nM. Mean [Ca2+]i following ‘add-back’ of different levels of extracellular Ca2+ were determined and plotted against % control response, to generate an estimated mean [Ca2+]i concentration–response curve for MCh-stimulated GFP-Tubby translocation [Fig. 4d(ii)]. From this curve, the [Ca2+]i required for half-maximal rescue of MCh-stimulated PLC activation can be estimated to be around 20 nM, indicating that low levels of intracellular Ca2+ are sufficient to facilitate the activation of PLC by Gαq/11-coupled receptor systems in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. These data were consistent with the observation that IP3 3-kinase over-expression had no effect on GFP-Tubby/eGFP-C1(2) responses (Fig. 2), as the residual Ca2+ responses to 100 μM MCh in cells over-expressing the 3-kinase (see Fig. 2b) would be sufficient to permit maximal agonist-mediated PLC activity.

Visualizing PIP2 in cultured rat hippocampal neurons using GFP-Tubby

We have previously used the eGFP-PH biosensor to investigate a variety of aspects of PLC signalling in cultured hippocampal neurons (see Nahorski et al. 2003) and have provided evidence that in this system, eGFP-PH translocation largely reflects changes in IP3 levels (Nash et al. 2004). Indeed, stimulation (with 1 mM MCh) of the endogenous mACh receptor population expressed in rat hippocampal neurons, cultured for 15 DIV, elicited a robust translocation of eGFP-PH from plasma membrane to cytosol. Following agonist washout, eGFP-PH re-localized to the plasma membrane [Fig. 5a(i)]. In cells pre-treated with either 1 μM (data not shown) or 10 μM Wort (Fig. 5a), similar temporal response profiles were observed, with no significant effect on either the peak height or plateau level of response relative to control cells (Table S3). These data were consistent with eGFP-PH translocation reporting changes in intracellular IP3 rather than depletion of plasma membrane PIP2 in cultured hippocampal neurons (Nash et al. 2004).

Fig. 5.

The effect of PI4-kinase inhibition on translocation of GFP-labelled biosensors in response to MCh in cultured neonatal rat hippocampal neurons. Representative images (i) and traces (ii) of eGFP-PH (a) and GFP-Tubby (b) translocation, in response to MCh (1 mM; black horizontal bar), in cultured rat hippocampal neurons (15 DIV) in the absence and presence of pre-incubated wortmannin (10 μM; grey horizontal bar). Data were expressed as a ratio change in cytosolic fluorescence emission (F) relative to the initial basal fluorescence (F0) and are representative of at least 11 cells from three or more coverslips. Scale bars, 10 μm.

However, until now, the ability selectively to image PIP2 in neurons has been lacking. We therefore expressed GFP-Tubby in cultured hippocampal neurons, where it exhibited a predominantly plasma membrane localization at rest and a substantial membrane-to-cytosol translocation on activation of the PLC pathway (Fig. 5b), similar to that observed in other cell backgrounds (Santagata et al. 2001 and this study). In control cells (and in those pre-treated with 1 μM Wort), GFP-Tubby re-localized to the plasma membrane on agonist washout, but in the presence of 10 μM Wort, the re-association of the probe to the plasma membrane was significantly slowed, with a plateau phase of response (∼35% of peak response) maintained until washout of Wort (Fig. S5b and Table S3). However, no significant differences in peak height were observed between control cells and those pre-incubated with either 1 or 10 μM Wort (Table S3).

Although the above data were qualitatively consistent with our findings in SH-SY5Y cells (see Table S2), the effect of Wort (10 μM) on GFP-Tubby translocation in hippocampal neurons in response to MCh was modest (Fig. S5b and Table S3). We therefore investigated whether exposure to agonist (MCh) for longer periods would further deplete plasma membrane PIP2 and therefore reveal a more pronounced effect of PI4-kinase inhibition on the re-localization of GFP-Tubby following agonist washout. In cells exposed to MCh (1 mM) for 3 min, GFP-Tubby cytosolic fluorescence decreased to baseline following agonist washout in control cells, while in cells pre-incubated with Wort (10 μM), the response was maintained at a plateau level until Wort was washed out (see Fig. S3). Over a number of experiments, plateau values (derived as % of peak response 240 s after peak) in control cells were only 6 ± 3% (n = 5), while those in cells pre-treated with Wort (10 μM) were significantly higher [61 ± 13% (n = 6); p<0.01; anova and Bonferroni’s post hoc test]. In contrast, GFP-Tubby responses in cells pre-treated with 1 μM Wort exhibited plateau values not significantly different to control [20 ± 8% (n = 5)]. Overall, these data suggest that, as in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, the translocation of GFP-Tubby reports dynamic changes in plasma membrane PIP2 in hippocampal neurons.

Discussion

We have used GFP-labelled biosensors to study, in real-time, dynamic changes in the levels of PIP2 and the products of PLC-mediated PIP2 hydrolysis, in intact living cells. Use of eGFP-PH, eGFP-C1(2) and GFP-Tubby has also allowed us to clarify the specificity of these probes and to address questions regarding the regulation of PLC activity in human neuroblastoma cells and primary neurons.

eGFP-PH detects IP3

A key finding of the present investigation is that translocation of eGFP-PH in response to mACh receptor stimulation in SH-SY5Y cells was dependent on changes in the cytosolic levels of IP3. Over-expression of IP3 3-kinase, to attenuate the IP3 response to MCh, substantially reduced eGFP-PH translocation, indicating a predominant role for IP3 in facilitating translocation of this biosensor. This is in agreement with the findings of previous studies in a variety of cell backgrounds, including Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (Hirose et al. 1999), Purkinje neurons (Okubo et al. 2001), Chinese hamster ovary cells (Nash et al. 2002) and hippocampal neurons (Nash et al. 2004). The over-expression of enzymes involved in the metabolism of IP3 to investigate the role of changes in IP3 levels in eGFP-PH translocation has been criticized, as this intervention also removes the IP3-mediated Ca2+ release which can potentiate PLC activity in some systems (Horowitz et al. 2005; Varnai and Balla 2006; Quinn et al. 2008). However, in this study, IP3 3-kinase over-expression had no effect on DAG production [determined using the DAG sensor eGFP-C1(2)], indicating that PLC activity was not compromised by IP3 3-kinase over-expression. This strongly suggests that the diminished eGFP-PH responses observed under these conditions reflect the IP3-dependence of the translocation. However, it should be noted that if DAG metabolism is also Ca2+-dependent (e.g. DAG kinase activity may be regulated by Ca2+; Yamada et al. 1997), IP3 3-kinase over-expression could decrease DAG metabolism, masking any decrease in DAG production resulting from reduced PLC activity.

Other reports have suggested the predominant role of PIP2 in mediating eGFP-PH translocation, so how can these divergent findings be reconciled? van der Wal et al. (2001) reported that inhibition of PIP2 re-synthesis with the PI4-kinase inhibitor phenylarsine oxide inhibited the re-localization of eGFP-PH to the plasma membrane. Indeed, our own experiments using inhibitors of PI4-kinase (Wort and LY294002) suggest that PIP2 re-synthesis is essential for the full re-association of eGFP-PH with the plasma membrane. However, as the eGFP-PH domain of PLCδ1 associates with PIP2 at the membrane, inhibition of PIP2 re-synthesis would be expected to impair the re-localization of the probe. Similarly, eGFP-PH translocation may be initiated by a rapid and profound depletion of PIP2 following the activation of a PIP2 5-phosphatase, in the absence of a rise in [IP3] (Suh et al. 2006; Quinn et al. 2008). However, our data and that of others (see earlier) indicate that the rapid initial translocation of the probe away from the membrane in response to agonist stimulation is more likely to be driven by the increase in IP3. This is further supported by our own calculations (see Fig. S4) and by the modelling simulations (based on empirically derived parameters) of Xu et al. (2003), who found that although changes in either PIP2 or IP3 were capable of translocating eGFP-PH, experimental data were better modelled by simulations in which IP3 levels changed, while the PIP2 concentration remained constant.

The observation that only very high (≥ 10 μM) levels of IP3 are able to initiate the translocation of eGFP-PH (van der Wal et al. 2001) provides another argument against the predominant role of IP3 in driving the translocation, as such levels of IP3 might not be achieved physiologically, even in response to maximal agonist stimulation. However, the higher IP3 concentrations are only required to translocate eGFP-PH because under those experimental conditions, [PIP2] remained at a constant (high) level, competing with IP3 for binding to eGFP-PH. In addition, Hirose et al. (1999) found that 1 μM IP3 was sufficient to induce a marked eGFP-PH translocation in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Xu et al. (2003) addressed these contrasting findings with further modelling work and found that the eGFP-PH response to a 1 μM bolus of IP3 was predicted to be highly sensitive to eGFP-PH expression levels, over only a 10-fold range, suggesting that such conflicting results might be because of differences in the expression levels of eGFP-PH biosensor. The relative contribution of PIP2 to the translocation of eGFP-PH may be greater in some cell types than others and may be influenced by a variety of experimental conditions (Varnai and Balla 2006), but it is clear that eGFP-PH does not provide a selective means of measuring dynamic changes in cellular PIP2.

GFP-Tubby detects PIP2

Tubby protein has previously been shown to bind with high affinity and selectivity to PIP2 in live cells, leading to the plasma membrane localization of a GFP-labelled form of the protein (Santagata et al. 2001). When expressed in SH-SY5Y cells, GFP-Tubby translocated in an agonist concentration-dependent manner in response to mACh receptor stimulation and this translocation was independent of changes in intracellular IP3, in agreement with a recent study using a modified version of the Tubby domain (Quinn et al. 2008). Crucially, in the presence of PI4-kinase inhibition, peak GFP-Tubby responses were significantly enhanced and were maintained beyond agonist washout. It was only on the removal of PI4-kinase inhibition (allowing PIP2 re-synthesis to resume) that GFP-Tubby was able to re-associate with the plasma membrane. Although the inhibitors used in these experiments (Wort and LY294002) are not specific for PI4-kinase, the consistency between the data obtained with each inhibitor (and the lack of effect of a lower, PI3-kinase-inhibiting concentration of Wort) strongly supports the notion that PI4-kinase activity is crucial for the re-association of GFP-Tubby to the plasma membrane. We therefore believe that GFP-Tubby translocation provides a selective means of visualizing changes in cellular PIP2, without the confounding influence of changes in IP3 concentration.

PLC signalling in living cells

The availability of selective fluorescent biosensors for IP3, DAG and PIP2, allowed us to perform a comprehensive investigation of PLC signalling in SH-SY5Y cells. Comparison of the kinetics and potencies of translocation for each biosensor highlighted some interesting differences. First, in response to the same agonist stimulus, GFP-Tubby translocated substantially more slowly than eGFP-PH, which in turn was marginally slower than eGFP-C1(2). Earlier biochemical measurements in SH-SY5Y cells indicate that the decrease in PIP2 observed on MCh stimulation reaches a peak at around 60 s (Willars et al. 1998), consistent with the time-course of GFP-Tubby translocation (t10–90 = 59 s), while IP3 mass responses peak more quickly (∼10–15 s; Willars et al. 1998). However, as GFP-Tubby consists of the full-length Tubby protein labelled with GFP, it is substantially larger (molecular mass ∼83 kDa) than either eGFP-PH (∼41 kDa) or eGFP-C1(2) (∼34 kDa). This raises the possibility that differences in the kinetics of the translocation of the three biosensors may reflect differences in their respective rates of diffusion. The second notable difference was the approximately fivefold lower potency of MCh for inducing translocation of GFP-Tubby, relative to eGFP-PH. If both probes are reporting the activation of the PLC pathway, it might be anticipated that a given agonist should elicit translocation of each biosensor with equal potency. However, while both eGFP-PH and GFP-Tubby localize to the plasma membrane under basal conditions, translocation of the former is primarily triggered by an increase in IP3, whereas that of GFP-Tubby relies purely on hydrolysis of PIP2. As the concentration of PIP2 is high at rest (360 pmol/mg protein in SH-SY5Y cells; Willars et al. 1998) it is possible that GFP-Tubby migration (between PIP2 molecules) competes with translocation of the probe into the cytosol, causing a rightward shift in the concentration–response curve relative to that reported by eGFP-PH (which, unlike GFP-Tubby, benefits from the ‘pull’ of the elevated cytosolic IP3 concentration). In addition, the translocation of GFP-Tubby reports the net change in concentration of its target molecule and will therefore reflect the influence of both synthesis and metabolism of this target. Given that PIP2 synthesis may be stimulated alongside PLC activation in some cases (e.g. Xu et al. 2003; Winks et al. 2005), it is conceivable that changes in PIP2 and IP3 levels might become uncoupled because of differences in their relative rates of synthesis/metabolism, despite the equivalent level of PLC activity resulting from mACh receptor activation. Although Gamper et al. (2004) found that M1 mACh receptor activation did not stimulate PIP2 synthesis (while bradykinin B2 receptor stimulation did) in rat superior cervical ganglion cells, this was considered to be because of the absence of a Ca2+ response to M1 mACh receptor activation in ganglion cells. As we observed robust Ca2+ responses to MCh in SH-SY5Y cells, it is possible that in this system mACh receptor activation could stimulate PIP2 synthesis and this requires further investigation.

Agonist-stimulated PLC activity is highly sensitive to [Ca2+]i

Agonist-stimulated PLC activity has been known for some time to be dependent on intracellular Ca2+ (Eberhard and Holz 1988) and the availability of fluorescently labelled biosensors for the substrate (PIP2) and both products (DAG and IP3) of PLC allowed us directly to visualize the Ca2+-sensitivity of PLC activity in neuroblastoma cells. Although direct activation of various PLC isoenzymes by Ca2+ in the micromolar range has been demonstrated (Allen et al. 1997; Hwang et al. 2005), we did not observe translocation of any of the three biosensors under investigation following treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with ionomycin (3 μM), even though this caused a substantial rise in intracellular Ca2+ (data not shown). In contrast, Varnai and Balla (1998) found that ionomycin treatment translocated eGFP-PH in NIH-3T3 cells, perhaps reflecting cell background-dependent differences in PLC sensitivity to Ca2+. However, removal of extracellular Ca2+ and depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores (reducing intracellular Ca2+ concentrations to the low nanomolar range) significantly attenuated MCh-stimulated translocation of eGFP-PH, GFP-Tubby and eGFP-C1(2). Although both eGFP-C1(2) and eGFP-PH responses were reduced by a similar amount following Ca2+ depletion/removal, GFP-Tubby responses were more substantially attenuated. This suggests that, in addition to inhibiting agonist-mediated PLC activity, lowering intracellular Ca2+ may have additional effects on the metabolism/synthesis of one or more of the signalling intermediates (PIP2/DAG/IP3) being detected by these biosensors. It is interesting to note that Quinn et al. (2008) found that translocation of R332H-Tubby (248–505)-yellow fluorescent protein was reduced under Ca2+-buffered conditions, while eGFP-PH was unaffected, providing further evidence that Tubby is more sensitive to the effects of Ca2+ on PLC activity.

We exploited the greater responsiveness of GFP-Tubby responses to changes in intracellular Ca2+ to demonstrate that agonist-mediated PLC activity appears to be highly sensitive to Ca2+ in SH-SY5Y cells. By adding Ca2+ back to the bath solution in a graded manner, we were able to demonstrate that maximal recovery was obtained by raising intracellular Ca2+ to between 100 and 200 nM, indicating the exquisite sensitivity of agonist-mediated PLC activity around the physiological resting Ca2+ concentration. Although this suggests a greater sensitivity than reported for carbachol-mediated stimulation of PLC-β1 in re-constituted vesicles (Biddlecome et al. 1996), our findings are in agreement with a number of earlier studies in a variety of other cell systems (Renard et al. 1987; del Rio et al. 1994; Young et al. 2003; Horowitz et al. 2005), indicating that agonist-stimulated PLC activity may be more sensitive to Ca2+ in its native environment. Our data also concur with earlier findings in SH-SY5Y cells, where carbachol-stimulated PLC activity (measured biochemically) was highly dependent on the free Ca2+ concentration in the range of 20–100 nM (Wojcikiewicz et al. 1994).

Although we have not identified the PLC isoenzyme(s) mediating agonist-stimulated PIP2 hydrolysis in the systems investigated in this study, PLC-β1 is the predominant isoform activated by mACh receptors in SH-SY5Y cells (Sorensen et al. 1998) and it is also highly expressed in the hippocampus (Rebecchi and Pentyala 2000). However, members of the novel PLC-η family are localized to neuronal cells and are also highly sensitive to Ca2+ (Cockcroft 2006). A direct physiological role for PLC-η enzymes in linking intracellular Ca2+ levels to PLC activity has yet to be established, but this remains an intriguing area for further study.

PIP2 and IP3 dynamics in primary neurons

Finally, we have shown that GFP-Tubby can be used to visualize dynamic changes in PIP2 in mature cultured hippocampal neurons. Stimulation of the endogenous mACh receptor population expressed in these cultures elicited a concentration-dependent translocation of GFP-Tubby. Inhibition of PI4-kinase activity with Wort led to a component of the GFP-Tubby response being maintained beyond agonist washout, although a longer agonist exposure (3 min) generated a more robust plateau in the response. This suggests that GFP-Tubby translocation reflects changes in plasma membrane PIP2, but that a more sustained stimulus may be required in this system sufficiently to deplete PIP2 (even in the presence of Wort) to prevent the probe re-associating with the membrane. In contrast, eGFP-PH translocation in response to MCh was unaffected by Wort, consistent with the probe detecting changes in IP3 levels in hippocampal neurons as reported by us earlier (Nash et al. 2004).

In summary, we have demonstrated the utility of GFP-Tubby as a fluorescent ‘biosensor’ for PIP2 and, in conjunction with well-characterized fluorescent probes for IP3 (eGFP-PH) and DAG [eGFP-C1(2)], have provided a comprehensive analysis of the Ca2+-sensitivity of PLC activity in live cells. Depolarization-induced Ca2+ entry has been shown to potentiate G protein-coupled receptor-driven PLC activity in neurons, with PLC-β1 acting as the ‘coincidence detector’ (Hashimotodani et al. 2005). In addition, we have previously reported that Gq/11-coupled receptor-mediated IP3 responses in single hippocampal neurons may be enhanced by coincident glutamate-mediated synaptic activity and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid receptor-activated Ca2+ entry (Nash et al. 2004, Willets et al. 2007). Given the important and distinct roles in neuronal physiology fulfilled by PLC substrate and products, the potential for this effector to provide the focal point for the integration of metabotropic and ionotropic signalling in neurons clearly merits further investigation. We anticipate that the use of selective biosensors for PIP2, IP3 and DAG will provide crucial new insights into the regulation of PLC activity at the single cell and subcellular level, facilitating the further study of this ubiquitous signalling pathway.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the following for making cDNA constructs available to us: Tobias Meyer, Stanford University [eGFP-PH and eGFP-C1(2)], Lawrence Shapiro, Columbia University (GFP-Tubby) and Mike Schell (Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, Bethesda (dsRed-IP3 3-kinase constructs). We also thank Prof. N. B. Standen (University of Leicester) for his comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain (Grant Number: 062495).

Glossary

Abbreviations used

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DIV

days in vitro

- eGFP

enhanced GFP

- eGFP-C1(2)

eGFP-protein kinase C-γ-C12

- eGFP-PH

eGFP-PH-PLCδ1

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- mACh

muscarinic acetylcholine

- MCh

methacholine

- PI3-kinase

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PLC

phospholipase C

- Wort

wortmannin

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Fig. S1 Concentration–response curves for eGFP-PLCδ1 PH (a), GFP-Tubby (b) or eGFP-PKCγ C1(2) (c) translocation in response to MCh in SH-SY5Y cells.

Fig. S2 Fluo-4 emission trace, illustrating relative changes in [Ca2+]i in a representative SH-SY5Y cell in response to changes in [Ca2+]e and thapsigargin treatment.

Fig. S3 Longer agonist treatment enhances PIP2 depletion in the presence of PI4-kinase inhibition in cultured neonatal rat hippocampal neurons.

Fig. S4 Simulation of the relationship between PIP2 concentration and eGFP-PH localization in SH-SY5Y cells.

Table S1 Concentration-dependence and kinetics of GFPlabelled biosensor translocations in response to MCh in SH-SY5Y cells.

Table S2 eGFP-PH and GFP-Tubby translocation in SH-SY5Y cells in response to MCh (1 mM), in the absence (control) and presence of wortmannin (Wort; 1 or 10 μM) or LY294002 (LY; 100 μM).

Table S3 eGFP-PH and GFP-Tubby translocation in cultured neonatal rat hippocampal neurons in response to MCh (1 mM), in the absence (control) and presence of wortmannin (Wort; 1 or 10 μM).

Please note: Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Allen V, Swigart P, Cheung R, Cockcroft S, Katan M. Regulation of inositol lipid-specific phospholipase Cδ by changes in Ca2+ ion concentrations. Biochem. J. 1997;327:545–552. doi: 10.1042/bj3270545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla T. Pharmacology of phosphoinositides, regulators of multiple cellular functions. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2001;7:475–507. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett PJ, Young KW, Nahorski SR, Challiss RAJ. Single cell analysis and temporal profiling of agonist-mediated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, Ca2+, diacylglycerol, and protein kinase C signaling using fluorescent biosensors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21837–21846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddlecome GH, Berstein G, Ross EM. Regulation of phospholipase C-β1 by Gq and m1 muscarinic cholinergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7999–8007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.7999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggon TJ, Shan WS, Santagata S, Myers SC, Shapiro L. Implication of Tubby proteins as transcription factors by structure-based functional analysis. Science. 1999;286:2119–2125. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft S. The latest phospholipase C, PLCη, is implicated in neuronal function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremona O, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in membrane traffic at the synapse. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:1041–1052. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P, Brown DA. Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:850–862. doi: 10.1038/nrn1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing GJ, Kim S, Nakanishi S, Catt KJ, Balla T. Characterization of a soluble adrenal phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase reveals wortmannin sensitivity of type III phosphatidylinositol kinases. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3587–3594. doi: 10.1021/bi9517493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard DA, Holz RW. Intracellular Ca2+ activates phospholipase C. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:517–520. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Calmodulin mediates Ca2+-dependent modulation of M-type K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003;122:17–31. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200208783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Reznikov V, Yamada Y, Yang J, Shapiro MS. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate signals underlie receptor-specific Gq/11-mediated modulation of N-type Ca2+ channels. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:10980–10992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3869-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimotodani Y, Ohno-Shosaku T, Tsubokawa H, Ogata H, Emoto K, Maejima T, Araishi K, Shin HS, Kano M. Phospholipase Cβ serves as a coincidence detector through its Ca2+ dependency for triggering retrograde endocannabinoid signal. Neuron. 2005;45:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Kadowaki S, Tanabe M, Takeshima H, Iino M. Spatiotemporal dynamics of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate that underlies complex Ca2+ mobilization patterns. Science. 1999;284:1527–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LF, Hirdes W, Suh BC, Hilgemann DW, Mackie K, Hille B. Phospholipase C in living cells: activation, inhibition, Ca2+ requirement, and regulation of M current. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;126:243–262. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S, Marsh SJ, Tinker A, Brown DA. PIP(2)-dependent inhibition of M-type (Kv7.2/7.3) potassium channels: direct on-line assessment of PIP2 depletion by Gq-coupled receptors in single living neurons. Pflügers Arch. 2007;455:115–124. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JI, Oh YS, Shin KJ, Kim H, Ryu SH, Suh PG. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel phospholipase C, PLC-η. Biochem. J. 2005;389:181–186. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert DG, Ghataorre AS, Nahorski SR. Muscarinic receptor binding characteristics of a human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH and its clones SH-SY5Y and SH-EP1. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;165:71–77. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90771-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling K, Schill NJ, Wagoner MP, Sun Y, Anderson RA. Movin’ on up: the role of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravall M, Mainen ZF, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Estimating intracellular calcium concentrations and buffering without wavelength ratioing. Biophys. J. 2000;78:2655–2667. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76809-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S, Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahorski SR, Young KW, Challiss RAJ, Nash MS. Visualizing phosphoinositide signaling in single neurons gets a green light. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:444–452. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi S, Catt KJ, Balla T. A wortmannin-sensitive phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase that regulates hormone-sensitive pools of inositol phospholipids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:5317–5321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash MS, Young KW, Willars GB, Challiss RAJ, Nahorski SR. Single-cell imaging of graded Ins(1,4,5)P3 production following G-protein-coupled-receptor activation. Biochem. J. 2001;356:137–142. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash MS, Schell MJ, Atkinson PJ, Johnston NR, Nahorski SR, Challiss RAJ. Determinants of metabotropic glutamate receptor-5-mediated Ca2+ and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate oscillation frequency. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:35947–35960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash MS, Willets JM, Billups B, Challiss RAJ, Nahorski SR. Synaptic activity augments muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-stimulated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production to facilitate Ca2+ release in hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49036–49044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oancea E, Meyer T. Protein kinase C as a molecular machine for decoding calcium and diacylglycerol signals. Cell. 1998;95:307–318. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81763-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oancea E, Teruel MN, Quest AF, Meyer T. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged cysteine-rich domains from protein kinase C as fluorescent indicators for diacylglycerol signaling in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:485–498. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo Y, Kakizawa S, Hirose K, Iino M. Visualization of IP3 dynamics reveals a novel AMPA receptor-triggered IP3 production pathway mediated by voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx in Purkinje cells. Neuron. 2001;32:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn KV, Behe P, Tinker A. Monitoring changes in membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in living cells using a domain from the transcription factor tubby. J. Physiol. 2008;586:2855–2871. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebecchi MJ, Pentyala SN. Structure, function, and control of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:1291–1335. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard D, Poggioli J, Berthon B, Claret M. How far does phospholipase C activity depend on the cell calcium concentration? Biochem. J. 1987;243:391–398. doi: 10.1042/bj2430391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio E, Nicholls DG, Downes CP. Involvement of calcium influx in muscarinic cholinergic regulation of phospholipase C in cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:535–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santagata S, Boggon TJ, Baird CL, Gomez CA, Zhao J, Shan WS, Myszka DG, Shapiro L. G-protein signaling through Tubby proteins. Science. 2001;292:2041–2050. doi: 10.1126/science.1061233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen SD, Linseman DA, Fisher SK. Down-regulation of phospholipase C-β1 following chronic muscarinic receptor activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;346:R1–R2. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer TP, Ahn S, Meyer T. Receptor-induced transient reduction in plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration monitored in living cells. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Hille B. Recovery from muscarinic modulation of M current channels requires phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate synthesis. Neuron. 2002;35:507–520. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Hille B. Regulation of ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Inoue T, Meyer T, Hille B. Rapid, chemically-induced changes of PtdIns(4,5)P2 gate KCNQ ion channels. Science. 2006;314:1454–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.1131163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker A, Cantley LC. Signalling through the lipid products of phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase. Nature. 1997;387:673–676. doi: 10.1038/42648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]-inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnai P, Balla T. Live cell imaging of phosphoinositide dynamics with fluorescent protein domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1761:957–967. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wal J, Habets R, Varnai P, Balla T, Jalink K. Monitoring agonist-induced phospholipase C activation in live cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15337–15344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willars GB, Nahorski SR, Challiss RAJ. Differential regulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-sensitive polyphosphoinositide pools and consequences for signaling in human neuroblastoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5037–5046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willets JM, Nash MS, Challiss RAJ, Nahorski SR. Imaging of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor signaling in hippocampal neurons: evidence for phosphorylation-dependent and -independent regulation by G-protein-coupled receptor kinases. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4157–4162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5506-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willets JM, Nelson CP, Nahorski SR, Challiss RAJ. The regulation of M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor desensitization by synaptic activity in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurochem. 2007;103:2268–2280. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winks JS, Hughes S, Filippov AK, Tatulian L, Abogadie FC, Brown DA, Marsh SJ. Relationship between membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and receptor-mediated inhibition of native neuronal M channels. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:3400–3413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3231-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcikiewicz RJ, Tobin AB, Nahorski SR. Muscarinic receptor-mediated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate formation in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells is regulated acutely by cytosolic Ca2+ and by rapid desensitization. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:177–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63010177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Watras J, Loew LM. Kinetic analysis of receptor-activated phosphoinositide turnover. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:779–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Sakane F, Matsushima N, Kanoh H. EF-hand motifs of alpha, beta and gamma isoforms of diacylglycerol kinase bind calcium with different affinities and conformational changes. Biochem. J. 1997;321:59–64. doi: 10.1042/bj3210059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KW, Nash MS, Challiss RAJ, Nahorski SR. Role of Ca2+ feedback on single cell inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate oscillations mediated by G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20753–20760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaika O, Lara LS, Gamper N, Hilgemann DW, Jaffe DB, Shapiro MS. Angiotensin II regulates neuronal excitability via phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-dependent modulation of Kv7 (M-type) K+ channels. J. Physiol. 2006;575:49–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaika O, Tolstykh GP, Jaffe DB, Shapiro MS. Inositol trisphosphate-mediated Ca2+ signals direct purinergic P2Y receptor regulation of neuronal ion channels. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:8914–8926. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1739-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.