Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether eradication of Helicobacter pylori relieves the symptoms of functional dyspepsia.

Design

Multicentre randomised double blind placebo controlled trial.

Subjects

278 patients infected with H pylori who had functional dyspepsia.

Setting

Predominantly secondary care centres in Australia, New Zealand, and Europe.

Intervention

Patients randomised to receive omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, amoxicillin 1000 mg twice daily, and clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 7 days. Patients were followed up for 12 months.

Main outcome measures

Symptom status (assessed by diary cards) and presence of H pylori (assessed by gastric biopsies and 13C-urea breath testing using urea labelled with carbon-13).

Results

H pylori was eradicated in 113 patients (85%) in the treatment group and 6 patients (4%) in the placebo group. At 12 months follow up there was no significant difference between the proportion of patients treated successfully by intention to treat in the eradication arm (24%, 95% confidence interval 17% to 32%) and the proportion of patients treated successfully by intention to treat in the placebo group (22%, 15% to 30%). Changes in symptom scores and quality of life did not significantly differ between the treatment and placebo groups. When the groups were combined, there was a significant association between treatment success and chronic gastritis score at 12 months; 41/127 (32%) patients with no or mild gastritis were successfully treated compared with 21/123 (17%) patients with persistent gastritis (P=0.008).

Conclusion

No convincing evidence was found that eradication of H pylori relieves the symptoms of functional dyspepsia 12 months after treatment.

Key messages

Dyspepsia (pain or discomfort centred in the upper abdomen) is frequently unexplained; such patients are classed as having functional (or non-ulcer) dyspepsia

H pylori gastritis is common in patients with functional dyspepsia but the benefits of treatment are controversial

No significant benefit in relief of symptoms was found between patients successfully treated for H pylori infection and those with persistent infection

Eradication of H pylori does not relieve the symptoms of functional dyspepsia

Introduction

Most patients with dyspepsia do not have any peptic ulceration or other disease1–4; they are classed as having functional dyspepsia. About 50% of patients with functional dyspepsia have co-existent Helicobacter pylori gastritis,3,5–7 but it is unclear whether H pylori causes symptoms in the absence of peptic ulceration.8–10

Carefully conducted trials should be able to determine whether or not H pylori is a cause of functional dyspepsia, as symptoms would be expected to abate when H pylori was eradicated.11 Previous trials, however, have been conflicting and the methods have been generally suboptimal.8,9 Moreover, few studies have tested whether eradication of H pylori improves dyspepsia long term. As it may take at least 12 months for gastritis, as confirmed by histology, to return to normal, prolonged follow up may be required to observe resolution of symptoms in functional dyspepsia.12,13

We postulated that H pylori is a direct cause of around 20% of cases of functional dyspepsia. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a controlled trial. The study protocol was approved by the appropriate ethics committees, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Subjects and methods

Overall, 278 consecutive patients were recruited from 40 centres in Australia, New Zealand, and nine European countries; 244 patients (89%) were from secondary care. The remaining 31 patients (11%) were from primary care and were recruited only from the United Kingdom. Twenty centres recruited six or more patients.

Protocol

Study population—

Dyspepsia was defined as pain or discomfort centred in the upper abdomen.1 We enrolled adult patients with dyspepsia for at least 3 months, normal endoscopic findings, and a positive result for H pylori on a screening test (Helisal, Cortecs Diagnostics, UK). Patients with oesophagitis (any mucosal break), Barrett’s oesophagus, gastric or duodenal ulceration, duodenal erosions, malignancy, more than five gastric erosions, or alarm symptoms were excluded. H2 receptor antagonists, prostaglandins, or prokinetics during the 7 days before enrolment, or proton-pump inhibitors, antibiotics, or bismuth during the 30 days before enrolment, were not permitted. Patients with documented peptic ulcer disease or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease were excluded.

Run-in period—

After endoscopy, patients were required to fill out a diary card with scores for their symptoms during a 7 day run-in period. Only patients who had at least 3 days of at least moderate dyspepsia symptoms were randomised. No study drug was dispensed during the run-in.

Treatment period—

Patients underwent a breath test using urea labelled with carbon-13 at the randomisation visit. They were randomised to receive either omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, amoxicillin 1000 mg twice daily, and clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 1 week. If patients had taken at least 12 out of 14 doses of drug or placebo they were considered to be compliant; no patients were withdrawn from the study because of poor compliance.

Follow up period—

The patients were followed up 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after cessation of treatment. Diary cards (filled out the week before each visit) were collected at each visit, quality of life forms were filled out by the patients at the 6 and 12 month visit, and a urea breath test and upper endoscopy were performed at the 3 and 12 month visits. A weak antacid (with a neutralising capacity of around 13 mmol of hydrochloric acid per tablet) was dispensed at each visit and its consumption was recorded. During follow up, patients could receive treatment for dyspeptic symptoms from their doctor but all drugs used were recorded.

Primary outcome measures

Patients recorded the severity of their dyspepsia symptoms on diary cards using a validated Likert scale comprising 7 grades: none, minimal, mild, moderate, moderately severe, severe, very severe.14

At each endoscopic evaluation, two antral and two corpus biopsy specimens were obtained. Specimens were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and with the Steiner silver method.

The biopsies were histologically graded.15 All specimens were reviewed by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist blinded to the treatment group. Urea breath testing was performed using a standard validated European protocol.16

At pre-entry, two test results for H pylori had to be positive; by screening test (Helisal rapid blood test or a rapid urease test) and by either urea breath testing or histological assessment.

After treatment, H pylori status was assessed at 3 and 12 months. If any of the gold standard assessments (urea breath test or histology) were positive, patients were considered to be positive for H pylori. If only one test result was available, the outcome of that test determined the H pylori status.

Secondary outcome measures

The gastrointestinal symptom rating scale was used to score dyspepsia symptoms. This validated instrument measures symptoms including abdominal pain.17,18 The psychological general well being index was used to score the patients’ quality of life. This validated instrument measures subjective well being.18–20

Patients were subdivided into symptom subgroups on the basis of their responses to the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale. Ulcer-like dyspepsia was defined as at least moderate stomach pain and hunger pain in the week before follow up. Dysmotility-like dyspepsia was defined by two or more of at least moderate bloating, nausea, stomach rumblings, or belching in the week before follow up. The subgroups were not mutually exclusive.

Statistical analyses

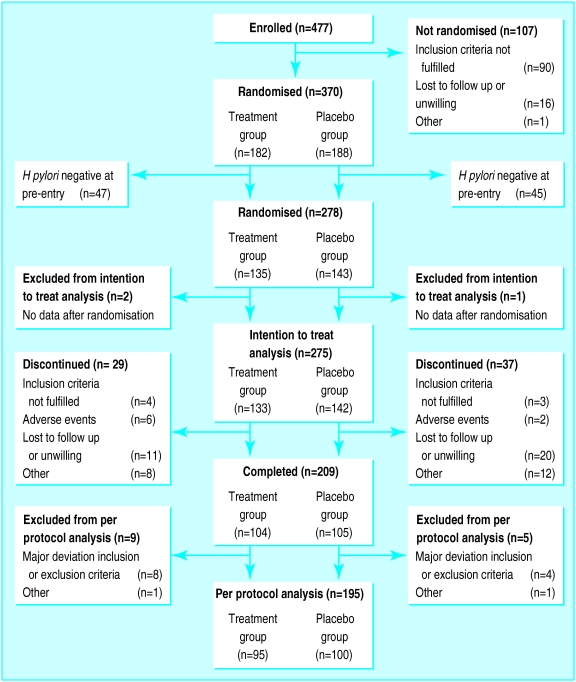

Patients were excluded from the intention to treat analysis who were negative for H pylori at pre-entry or who were without any assessment of treatment efficacy after randomisation (fig 1). The treatment groups were compared for symptom relief with a Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by country and for healing of gastritis with a Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by baseline gastritis.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through trial

Patients who reported on the diary card no more than minimal dyspepsia symptoms during any of the 7 days before the 12 month visit were considered a priori to be a treatment success.

Chronic gastritis was considered healed when both antrum and corpus specimens had an inflammation score of zero.15

The treatment groups were compared for change in the total score of the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale and psychological general well being index from the first visit to the last visit in the study, using the baseline value as a covariate in an analysis of covariance model.

With 275 patients, the power of the study was 94% provided the true proportions of responders was 20% and 40% in the two groups (assuming an α level of 0.05 based on a two sided χ2 test). The placebo response was based on data for symptom turnover.21

Randomisation was in blocks of four in proportions of 1:1 according to a computer generated list.

Identical placebos were used. Investigators and patients were blinded to all data, including H pylori assessments after randomisation, until the study was fully completed.

Results

One hundred and thirty five patients (52 men) were randomised to treatment and 143 patients (48 men) were randomised to placebo (fig 1). Three patients (two in the treatment group and one in the placebo group) were withdrawn from the analysis because of unavailability of data after randomisation.

The two groups were well balanced for demographic and clinical features (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline data of patients allocated omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin or placebo. Values are number (percentage) of patients, unless stated otherwise

| Baseline characteristic | Treatment group (n=133) | Placebo group (n=142) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 51 (14) | 49 (13) |

| Male | 51 (38) | 47 (33) |

| Ethnic origin: | ||

| White | 130 (98) | 140 (99) |

| Smoker | 26 (20) | 39 (27.5) |

| Alcohol use | 50 (38) | 51 (36) |

| Duration of dyspepsia >1 year | 104 (78) | 106 (75) |

Analysis

Eradication of H pylori and healing of gastritis

Both urea breath testing and histology results were available for 237 patients (86%). At 12 months, 113 patients (85%) in the treatment arm had been successfully cured of H pylori infection compared with 6 patients (4%) in the placebo group. However, 108 patients (81%) in the treatment group had no or mild chronic gastritis at 12 months compared with 18 patients (13%) in the placebo group (table 2). Overall, 98% of patients consumed at least 12 of 14 doses in both groups.

Table 2.

Main study outcomes 12 months after treatment with omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin or placebo. Values are number (percentage) unless stated otherwise

| Variable | Type of analysis | Treatment group | Placebo group | % difference (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment success* | Intention to treat | 32 (24) | 31 (22) | 2 (−8 to 12) | 0.7 |

| n=133 | n=142 | ||||

| Treatment success* | Per protocol | 27 (28) | 29 (29) | −1 (−13 to 12) | 0.9 |

| n=95 | n=100 | ||||

| Active chronic gastritis grade 0† | Intention to treat | 94 (71) | 4 (3) | 69 (61 to 77) | <0.001 |

| Chronic gastritis grade 0‡ | Intention to treat | 25 (19) | 1 (1) | 18 (12 to 25) | <0.001 |

| Chronic gastritis grades 0 and 1‡ | Intention to treat | 108 (81) | 18 (13) | 68 (59 to 76) | <0.001 |

| n=133 | n=142 |

No or only minimal pain or discomfort centred in upper abdomen over 7 days before 12 month visit.

Presence of polymorphonuclear cells.

Presence of mononuclear cells.

Symptom relief

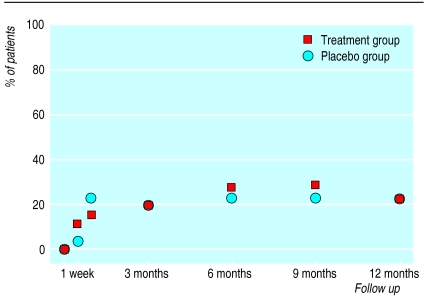

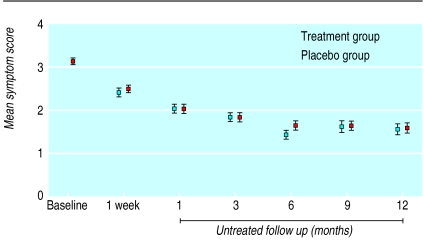

By an intention to treat analysis, 32 patients (24%) in the treatment group and 31 patients (22%) in the placebo group were successfully treated (minimal or no dyspepsia) at 12 months (table 2). There was no significant difference in treatment success among those who were negative for H pylori (35, 29%) and those who remained positive for H pylori (28, 21%). At the 12 month follow up, no dyspepsia symptoms were reported by 20 patients (15%) in the treatment group and 16 patients (11%) in the placebo group. A similar proportion of patients in each treatment arm had no or minimal dyspepsia symptoms at each follow up (fig 2). The mean symptom score was not significantly different at each time point (fig 3). There was no inhomogeneity among countries (Breslow-Day test, P>0.20).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with no more than minimal dyspepsia symptoms on basis of diary card data (per protocol analysis)

Figure 3.

Mean symptom score and SEM on diary cards at follow up visits

Mean antacid consumption over 12 months did not differ significantly between treatment (0.53 tablets per day) and placebo groups (0.65). Five patients (one in the treatment group and four in the placebo group) had treatment success according to the diary cards but were considered treatment failures in the analysis because they took a gastrointestinal drug other than antacid within 2 weeks of the 12 month visit.

In the ulcer-like dyspepsia group, treatment success was reported by 17/68 patients (25%) in the treatment group and 12/58 patients (21%) in the placebo group. The corresponding results for dysmotility-like dyspepsia were 14/78 patients (18%) in the treatment group and 13/73 patients (18%) in the placebo group.

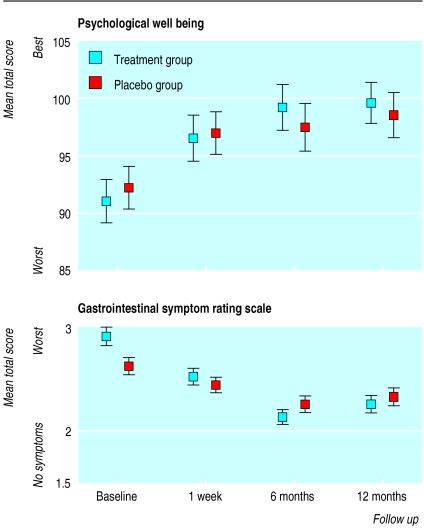

The change from baseline to last visit between the treatment groups was not significant for either the psychological general well being index or the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (fig 4).

Figure 4.

Intention to treat analysis showing mean (SEM) scores for quality of life and severity of symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia. Possible psychological well being index scores (top) ranged from 132 (best) to 22 (worst); possible gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (bottom) mean scores ranged from 1 (no symptoms) to 7 (worst symptoms)

Gastritis scores and symptom relief—

There was no association between the severity of symptoms at baseline and gastritis scores on initial biopsies. Patients at follow up were subdivided regardless of treatment into those with a chronic gastritis score of 0 or 1 (none or mild gastritis) and those with a score of 2 or 3 (moderate or severe gastritis) in a secondary analysis. At the 12 month follow up, 41/127 patients (32%) with no or mild gastritis were treatment successes (no or minimal dyspepsia) compared with 21/123 patients (17%) with moderate or severe gastritis (P=0.008). This association was not explained by age. Of the 41 patients with none or mild gastritis at follow up, only nine had received placebo (of whom only one had complete resolution of gastritis and eight had mild gastritis).

Discussion

Few large trials have rigorously evaluated the role of H pylori eradication in functional dyspepsia, and the results are conflicting.22,23 We found no convincing evidence that successful eradication of H pylori infection relieves or reduces symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia over 12 months.

Trial design issues

We aimed to overcome previous methodological limitations.8,9 In particular, the outcome measures were valid and responsive to change.14,17–20 Scrupulous attention was paid to blinding of patients and investigators. Prospective assessment of symptoms reduced the issue of recall bias.9

Predictors of symptom relief

A persistent inflammatory response could promote the development of dyspepsia.11 We observed an association between healing of chronic gastritis and symptom relief but this secondary analysis requires confirmation.

A few studies have observed that treatment response was limited to those patients with ulcer-like dyspepsia, but no link between dyspepsia subgroups and H pylori eradication was evident in the present study.13,24 Although our results may be generalisable to secondary care, we cannot exclude the possibility that such patients have more resistant symptoms than those in primary care where trials are needed.

Management implications—

A popular management strategy in otherwise healthy young patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia is to non-invasively test for H pylori and to treat all infected cases.25 Although controversial, such a strategy may have a number of potential benefits.26 On the basis of our results, however, only a minority who are treated would be likely to gain long term symptomatic relief, because most infected patients with dyspepsia have functional dyspepsia rather than peptic ulcer disease.25

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Optimal Regimen Cures Helicobacter Induced Dyspepsia Study Group: S Kiilerich, L Weywadt, U Tage-Jensen (Denmark); RJLF Loffeld, JA Beker, PWE Haeck (Netherlands); B Collins, J Karrasch, M Korman, R Watts (Australia); K Vetvik, K Hveem, J Østborg, S Wetterhus (Norway); GO Barbezat (New Zealand); A Obrador, J Viver, E Quintero, M Torres, J Hinojosa (Spain); M Rasmussen, R Grönfors, PE Wingren (Finland); J Hosie, S Rowlands, M Scott, C Stoddard, G Walker (United Kingdom); MA Bigard, D Goldfain, JY Begue, D Schmitz (France); Z Döbrönte, L Juhász, L Lakatos, Z Tulassay (Hungary). We also thank Ola Junghard, Niilo Havu, and Gudrun Sjögren from Astra Hässle, Sweden.

Footnotes

Funding: Astra Hässle (Molndal, Sweden).

Competing interests: NJT has been a consultant for Astra Hässle (Sweden) and Abbott Laboratories (USA). EB-S is an employee of Astra Hässle.

References

- 1.Talley NJ, Colin-Jones D, Koch KL, Koch M, Nyrén O, Stanghellini V. Functional dyspepsia. A classification with guidelines for diagnosis and management. Gastroenterol Int. 1991;4:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernersen B, Johnsen R, Bostad L, Straume B, Sommer AI, Burhol PG. Is Helicobacter pylori the cause of dyspepsia? BMJ. 1992;304:1276–1279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6837.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong D. Helicobacter pylori infection and dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(suppl 215):38–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bytzer P. Diagnosing dyspepsia—any controversies left? Gastroenterology. 1996;110:302–306. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.agast960302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss RM, Wang TC, Kelsey PB, Campton CC, Ferraro MT, Perez-Perez G, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with dyspeptic symptoms in patients undergoing gastroduodenoscopy. Am J Med. 1990;89:464–469. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90377-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schubert TT, Schubert AB, Ma CK. Symptoms, gastritis, and Helicobacter pylori in patients referred for endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:357–360. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70432-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nandurkar S, Talley NJ, Xia H, Mitchell H, Hazell S, Jones M. Dyspepsia in the community is linked to smoking and aspirin use but not to Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1427–1433. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.13.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talley NJ. A critique of therapeutic trials in Helicobacter pylori—positive functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJO, Cleary C, Talley NJ, Peterson TC, Nyren O, Bradley L, et al. Drug treatment of functional dyspepsia: a systematic analysis of trial methodology with recommendations for design of future trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:660–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laheij RJF, Jansen JBMJ, Vandelisdonk EH, Verbeek ALM. Symptom improvement through eradication of Helicobacter pylori with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Alimen Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:843–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.86258000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talley NJ, Hunt RH. What role does Helicobacter pylori play in non ulcer dyspepsia? Arguments for and against H. pylori being associated with dyspeptic symptoms. Gastroenterology. 1997;(suppl 6):67–77S. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy C, Patchett S, Collins RM, Beattie S, Keane C, O’Morain C. Long term prospective study of Helicobacter pylori in non-ulcer dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:114–119. doi: 10.1007/BF02063953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilvarry J, Buckley MJM, Beattie S, Hamilton H, O’Morain CA. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori affects symptoms in non-ulcer dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:535–540. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junghard O, Talley NJ, Wiklund I. Validation of seven graded diary cards for severity of dyspeptic symptoms in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Europ J Surg. 1998;583:106–111. doi: 10.1080/11024159850191355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. International workshop in the histology of gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dominguez-Munoz JE, Leodolter A, Sauerbruch T, Malfartheiner P. A citric acid solution is an optimal test drink in the 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1997;40:459–462. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.4.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:75–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1008841022998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goves J, Oldring JK, Kerr D, Dallara RG, Roffe EJ, Powell JA, et al. First line treatment with omeprazole provides an effective and superior alternative strategy in the management of dyspepsia compared to antacid/alginate liquid: a multicentre study in general practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:147–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.0284f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiklund I, Bardhan KD, Muller-Lisner S, Bigard MA, Bianchi-Porro G, Ponce J, et al. Quality of life during acute and intermittent treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease with omeprazole compared with ranitidine. Results from a multicentre study. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimenas E, Glise H, Hallerback B, Hernqvist H, Svedlund J, Wiklund I. Well-being and gastrointestinal symptoms among patients referred to endoscopy owing to suspected duodenal ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:1046–1052. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., III Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:165–177. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McColl K, Murray L, El-Omar E, Dickson A, El-Nujumi A, Wirz A, et al. Symptomatic benefit from eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1998;26:1869–1874. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blum A, Talley NJ, O’Morain C, Veldhuyzen Van Zanten S, Labenz J, Stolte M, et al. Lack of effect of treating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1998;26:1875–1881. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trespi E, Broglia F, Villani L, Luinetti O, Fiocca R, Solcia E. Distinct profiles of gastritis in dyspepsia subgroups. Their different clinical responses to gastritis healing after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:884–888. doi: 10.3109/00365529409094858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talley NJ, Silverstein MD, Agreus L, Nyren O, Sonnenberg A, Holtmann G. AGA technical review: evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1997;114:582–595. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Axon A, Forman D. Helicobacter gastroduodenitis: a serious infectious disease. BMJ. 1997;314:1430–1431. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7092.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.