Abstract

Proteasome plays fundamental roles in the removal of oxidized proteins and in the normal degradation of short-lived proteins. Previously we have provided evidences that the impairment in proteasome observed during the replicative senescence of human fibroblasts has significant effects on MAPK signaling, proliferation, life span, senescent phenotype and protein oxidative status. These studies have demonstrated that proteasome inhibition and replicative senescence caused accumulation of intracellular protein carbonyl content. In this study, we have investigated the mechanisms by which proteasome dysfunction modulates protein oxidation during cellular senescence. The results indicate that proteasome inhibition during replicative senescence have significant effects on the intra and extracellular ROS production in vitro. The data also show that ROS impaired the proteasome function, which is partially reversible by antioxidants. Increases in ROS after proteasome inhibition correlated with a significant negative effect on the activity of most mitochondrial electron transporters. We propose that failures in proteasome during cellular senescence lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS production and oxidative stress. Furthermore, it is likely that changes in proteasome dynamics could generate a pro-oxidative condition at the immediate extracellular microenvironment that could cause tissue injury during aging, in vivo.

Keywords: Proteasome inhibition, ROS, oxidative stress, cellular senescence, mitochondria

INTRODUCTION

Replicative senescence of human diploid fibroblasts is characterized by important alterations in gene expression and structural phenotype, loss in the responsiveness to mitogens and failures in proliferative capacity [1, 2]. Failures in proliferative capacity in senescent fibroblasts has been associated with a decrease in the expression of the early response genes c-fos, Id-related genes [3, 4], reduced DNA binding activity of SRF and AP-1 transcription factors to the c-fos promoter [5]. In addition, upstream regulation at the level of the ERK/MAP kinase pathway plays an important role in the decline in c-fos expression and control of proliferation. Indeed, we have shown that senescent cells display significantly reduced levels of nuclear p-ERK [6], which correspond with increased activity of the nuclear ERK phosphatase MKP2 [7]. Recently we have proposed a critical role for MKP-2 in the control of nuclear ERK activity and modulation of the senescent phenotype [8]. The control of ERK activity is probably due to loss of degradation of MKP2 by the proteasome since its activity is significantly decreased during fibroblast senescence [7]. These studies suggest that the decreased activity of the proteasome may lead to increased levels of nuclear MKP-2 resulting in decreased ERK activity. This could play a pivotal role in the decreased binding of SRF to the c-fos promoter leading to impaired cell proliferation in response to external stimuli.

The proteasome is a large multicatalytic protease that constitutes the major non-lysosomal proteolytic activity in the cell. It is located in the nucleus and the cytoplasm, where it associates primarily with the endoplasmic reticulum [9]. Proteasome is mainly associated with the elimination of abnormal, oxidized and misfolded proteins [10, 11]. Recently, it has been suggested that it may be part of cellular defense mechanism by controlling protein oxidative damage [12], [13], [14, 15]. Proteasome function is also necessary for the normal turnover of short-lived proteins involved in cell cycle progression [16], gene expression [17], apoptosis [18, 19], antigen presentation [20] and signal transduction [7, 21, 22].

Several studies have also demonstrated an age-dependent decline in proteasome function. Proteasome activity declines with age in human epidermis [23], in CD45RA/CD45RO subsets of human T lymphocytes [24] and in rat heart [25], muscle [26], retina [27], lung, kidney, liver and spinal cord [28]. Decline in proteasome activity has been observed during replicative senescence, in keratinocytes [29], human MRC-5 [30] and WI-38 fibroblasts [7, 31]. The functional impairment in proteasome may have severe consequences on cellular homeostasis and survival during the senescence of human fibroblasts. A critical role for proteasome as mediator of cellular aging and oxidative stress has been proposed in human fibroblasts [7, 31]. We have demonstrated that hat partial and non-toxic inhibition of proteasome in early-passage fibroblasts leads to a significant impairment in cell proliferation, shortening in the replicative life span and generation of a premature senescence-like phenotype [32].

Mitochondria are a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The increased levels in mitochondrial ROS production also may lead to loss of mitochondrial function and decreased energy production causing aging [33, 34]. In mitochondria, the electron transport chain (ETC) is the main source of ROS [35]. Impairment in ETC is associated with increase in ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction. Interestingly, many diseases involving mitochondrial dysfunction are also known to have significant level of proteasome inhibition. For example, proteasome inhibition reduced dramatically the activities of complex I and II in neural mitochondria [36].

In this report, we have studied the mechanisms by which proteasome dysfunction modulates protein oxidation during cellular senescence of human fibroblasts. The results indicate that alterations in proteasome function increase the intracellular and extracellular production of reactive oxygen species and protein carbonyl content. This correlates with a decreased activity of mitochondrial electron transporters similar to that observed in senescent cells. These results suggest that proteasome inhibition observed during replicative senescence may have detrimental effects on mitochondrial homeostasis and oxidative stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Media and serum were purchased from Life Technologies Inc (Herndon, VA). Epoxomicin, MG115, and N-succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC (Suc-LLVY-AMC), were purchased from Biomol Research Laboratories Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Amplex® Red assay kit was from Molecular Probes Inc. (Eugene, OR). Oxyblot™ kit was purchased from Chemicon Int. (Serologicals Corporation, Norcross, GA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma.

Cell Culture

WI-38 fetal human diploid fibroblasts were grown at 37°C in MEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.2% Na-bicarbonate and 10% FBS as previously described [37]. Cells were seeded at 1×104 cells/cm2 and grown for three days. Cells were considered to be early passage (young cells) when less than 50% of their replicative lifespan was completed. Cultures at the end of the replicative lifespan (senescent cells) were those unable to complete one population doubling during a four-week period with weekly re-feeding. Proteasome inhibitors were prepared in DMSO (0.0025% DMSO final concentration in the cultures).

Proteasome activity

WI-38 fibroblasts were washed twice with cold PBS, collected with a rubber policeman and resuspended in ice-cold proteasome buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT). After 10 min on ice, cells were lysed by 30 strokes in a glass-teflon Dounce homogenizer. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 1 hour at 10,000 × g at 4°C and the supernatant was used for the assay. Chymotrypsin-like (CT-like) proteasome activity was assayed at 37°C using 10 μg of protein extracts in proteasome buffer in the presence of 100 μM Suc-LLVY-AMC. The reaction was monitored by fluorimetric measurements every 10 min for 1 h (excitation 350 nm, emission 460 nm) in a Synergy HT Multi-Detection microplate reader and software KC4 v.3.0 (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc). Proteasome activity corresponds to the remaining activity after subtraction of the activity determined in the presence of 20 μM of epoxomicin.

SA β-gal staining

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-gal) positive cells were detected as previously described [38]. The cells were washed with PBS and fixed for 5 min with 2% formaldehyde-0.2 % glutaraldehyde. The cells were washed and incubated overnight at 37 °C in staining solution containing 1 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-inolyl-β-D-galactoside, 40 mM citric acid/phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM sodium ferricyanide, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2. Finally, the cells were washed with PBS and counted. SA β-gal positive cells were expressed as a percentage of the total.

Protein carbonyl content

Protein carbonyl groups were quantified by using Oxyblot™ a commercially available kit from Chemicon Int. (Serologicals Corporation, Norcross, GA). Young WI-38 fibroblasts both control or after different treatments were washed twice with cold PBS, collected with a rubber policeman and lysed by using a glass-teflon Dounce homogenizer. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 1 hour at 10,000 × g at 4°C. Fifteen μg of total proteins were derivatized at room temperature with 2,4 dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) for 15 min in the presence of 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and 6% SDS. Protein carbonyl groups were analyzed by Western blot using an anti-DNP antibody.

Mitochondria isolation

WI-38 fibroblasts cultured in P150 plates were washed twice with cold PBS, collected with a rubber policeman and resuspended in a solution containing 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1mM MgCl2. Cells were centrifuged 5 min at 250 g, resuspended in 1 volume of the same solution and 10 volumes of 10 mM Tris (pH 6.7), 10 mM KCl, 0.15 mM MgCl2 and lysed manually by 30 strokes in a glass-teflon Dounce homogenizer. The homogenates were resuspended in 0.25 M sucrose, 10mM Tris (pH 6.7), 10 mM KCl, 0.15 mM MgCl2, and centrifuged at 700 g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,500 g for 30 minutes and mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 0.25M sucrose, 10mM Tris, 1mM EDTA. Mitochondrial pellet was washed in 0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris, 0.15 mM MgCl2, centrifuged at 12,500 g for 30 minutes, and resuspended in a 50 μL of Tris 10 mM, Sucrose 0.25 M.

Determination of enzymatic activity of respiratory chain complexes I–V

The mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 750 mM 6-aminocaproic acid/50 mM Bis Tris pH 7.0, 1% protease cocktail inhibitor I (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) and 1% final concentration of n-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The activities of the electron transport complexes were measured using two different methods: Blue Native Gel (BN-PAGE) [39] and spectrophotometric assay [40] (Darley-Usmar V). Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) assay was measured as previously described in Mansouri et al. [41]. Briefly, the mitochondrial extracts (50 μg protein plus 2 μL 5% Serva Blue G in 750 mM aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl), were separated using a 5–13% gradient BN-PAGE with 4% stacking gel. After electrophoresis, the protein banding pattern was scanned and quantified by densitometry. The enzymatic colorimetric reactions were performed on the BN-PAGE gel slices. Complex I (NADH-oxidoreductase) activity was determined by incubating the gel slices with 2 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1 mg/mL NADH, and 2.5 mg/mL Nitro Blue Tetrazolium. Complex IV (COX) activity was estimated by incubation of the BN-PAGE gels with 5 mg 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB), 0.1 mL catalase (20 μg/mL), 10 mg cytochrome c, and 750 mg sucrose. Complex V (ATPase) activity was estimated by incubating the BN-PAGE gel slices in 35 mM Tris, 270 mM glycine, 14 mM MgSO4, 0.2% Pb(NO3)2 and 8 mM ATP. Violet colored complex I, red-stained complex IV or white-black complex V were scanned using Alpha Imager densitometer (Alpha Innotech). The relative activities of the complexes were expressed as colored band intensity/coomassie blue band intensity ratios. For spectrophotometric assay, 10 μg of mitochondrial proteins in respiration buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10mM KH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EGTA) were used to measure complexes activities for complex I to IV. The activity for complex I was determined by monitoring the oxidation of NADH at 340 nm at 30°C, using ubiquinone-2 as an electron acceptor [42]. Complex II activity was measured by the succinate-dependent reduction of 2, 6–Diclorophenolindophenol at 600 nm and 30°C using ubiquinone-2 as an electron acceptor [43]. Complex III activity was measured by reduction of cytochrome c Fe+3 at 550 nm using Decylubiquinol-2 as an electron donor. KCN was added to inhibit Complex IV activity during the measurements of the complexes I to III. The Complex IV activity was determined by monitoring the oxidation of cytochrome c Fe+2 at 550 nm. The data are expressed in μmol/min/mg protein.

Determination of the protein levels in ETC complexes

The protein levels for ETC subunits for complex I, complex II, complex III, complex IV and complex V were determined by Western blotting of the mitochondrial fraction purified from cells cultured in the absence or presence of proteasome inhibitors. Equal amounts of total proteins (30μg) were separated by 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. ETC subunits protein levels for each complex were determined by specific monoclonal antibodies obtained from Invitrogen-Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA), (Complex I: 20 kDa subunit; Complex II: 30 kDa subunit; Complex III: Core II subunit; Complex IV: IV subunit; Complex V: ATPase β subunit). Protein bands were visualized using the ECL-Plus Kit (Amersham-Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ).

ROS determination

Intracellular ROS production was determined by using 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) as previously described [44] with the following modifications. Early and late-passage WI-38 fibroblasts were seeded at 1×104 cells/cm2 into 96-well μClear® Bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One, Inc., Longwood, FL) one day before the experiment. After 24 hr of incubation with proteasome inhibitors, the cells were washed twice with KRPG and incubated with 1 μM DCFH-DA in MEM 1% FBS for 30 min, at 37 °C in the incubator. The cells were washed twice with KRPG and the plates were observed under fluorescent microscope using FITC filter. For quantitative determinations, cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with DCFH-DA. After two washes with KRPG, the cells were harvested with a Teflon scrapper and sonicated. An aliquot of the homogenates were placed in 96-well μClear® Bottom plates and the fluorescence at 530 nm was measured after excitation at 485 nm. Fluorometric determinations were performed in a Synergy HT Multi-Detection microplate reader, using the software KC4 v.3.0 (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT).

Extracellular levels of H2O2 were determined by incubating cells with N-acetyl-3, 7-dihydroxyphenoxazine (Amplex® Red), as described in the Molecular Probes kit with the following modifications. Early and late-passage WI-38 fibroblasts were seeded at 1.5 ×104 cells/cm2 into 96-well μClear® Bottom plates. After 24 hr, the cells were washed twice with KRPG, and incubated with 100 μL of reaction mixture containing 50 μM Amplex® Red and 0.1 U/mL HRP (Horseradish peroxidase in KRPG) for 2 hr at 37 °C in the presence or absence of proteasome inhibitors. The controls included catalase, which was added into the reaction mixture at 1,000 U/mL final concentration, or HPR control where HRP was replaced with KRPG buffer. The plates were read at 590 nm (Ex: 530, Em: 590nm) in a Synergy HT Multi-Detection microplate reader.

Statistics

Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were done at least in triplicate. Data are expressed as mean +/− SEM and were analyzed by two samples Student t test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Proteasome inhibition, protein oxidation and antioxidants

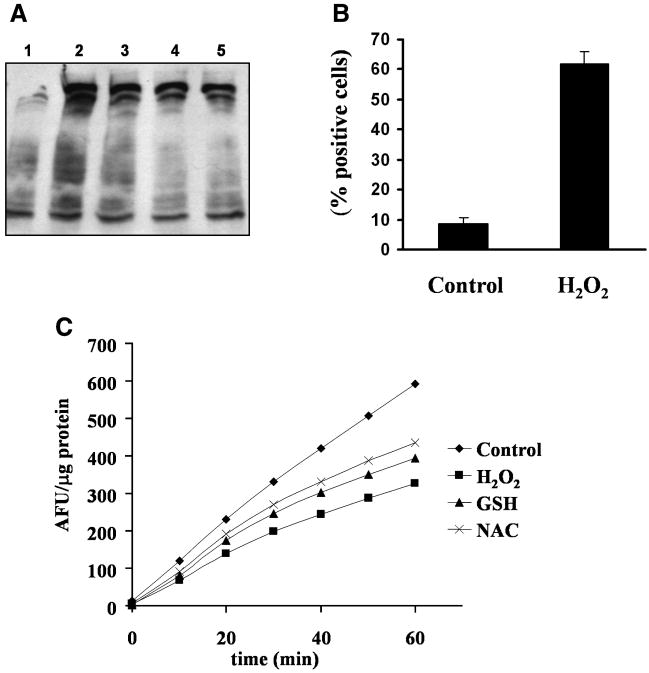

We [7], and others [31] have reported partial inhibition in proteasome activity during replicative senescence of human WI-38 fibroblasts. Impairment in proteasome function is a common pattern observed in several organs and tissues during in vivo aging. By using non-toxic and partially inhibitory doses of proteasome inhibitors that recapitulate the inhibition observed in senescent cells, recently we have reported that inhibition of proteasome leads to increase in protein carbonyl content, at comparable levels to that observed in senescent cells [45]. Here, we investigated whether the increase in protein oxidation in response to proteasome inhibition was due to impairment in proteasome activity by itself or due to an increased production of reactive oxygen species. Figure 1A shows that the proteasome inhibitor MG115-induced protein carbonyl content was partially decreased by pre-incubation with antioxidants GSH and NAC. This result suggests that failures in proteasome function could be associated with the induction of ROS production. However, the effects of these antioxidants may also be due to direct effect on proteasome function. To elucidate the role of the oxidative stress on proteasome activity under conditions relevant to cellular senescence, we treated young WI-38 fibroblasts with 150 μM H2O2 for 2 hr, followed by 3 days of incubation in MEM 10% FBS. Figure 1B shows that H2O2 induced premature generation of a senescent phenotype as indicated by a dramatic increase in cells with senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity, a biomarker of cellular aging [38]. Interestingly, the generation of this pre-mature senescent condition also caused a parallel decrease in 20S chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity, which was partially prevented by the presence of the antioxidants NAC and GSH (Figure 1C). These results suggest that the increase in protein carbonyl content observed after proteasome inhibition is associated with impairments in proteasome function and increase in ROS production.

Fig. 1. Effect of oxidative stress on proteasome, protein oxidation and cellular senescence.

(A). Effects on protein oxidation. Early passage cells were pre-incubated 24 hours in the presence or absence of glutathione (GSH) or N-acetylcysteine (NAC) followed by 24 h of treatment with o without 1 μM MG115. Cells were lysed and fifteen μg of total proteins were DNPH-derivatized, and analyzed by Western blot using an anti-DNP antibody. Figure shows in a representative blot: 1. Control (DMSO); 2. 1 μM MG115; 3. 100 μM GSH/1 μM MG115; 4. 200 μM GSH/1 μM MG115; 5. 100 μM NAC/1 μM MG115. (B). Effects on cellular senescence. Early passage cells were incubated 2 hours with 150 μM H2O2 and cultured in MEM 10% FBS by 3 days. Cells were stained for β-gal as indicated in Materials and Methods. At least four hundred cells were counted, and positive cells were expressed as a percentage of the total. Control: cells without H2O2 treatment. (C). Effects on proteasome activity. Young cells after H2O2 treatment were cultured in MEM 10% FBS by 3 days in the absence or presence of 100 μM GSH (GSH) or 100 μM NAC (NAC). Control: cells without H2O2 treatment; H2O2: cells with H2O2 treatment without antioxidants. The graph shows a representative time course experiment. CT-like 20S proteasome activity was assayed as indicated in Materials and Methods.

Proteasome inhibition and ROS production

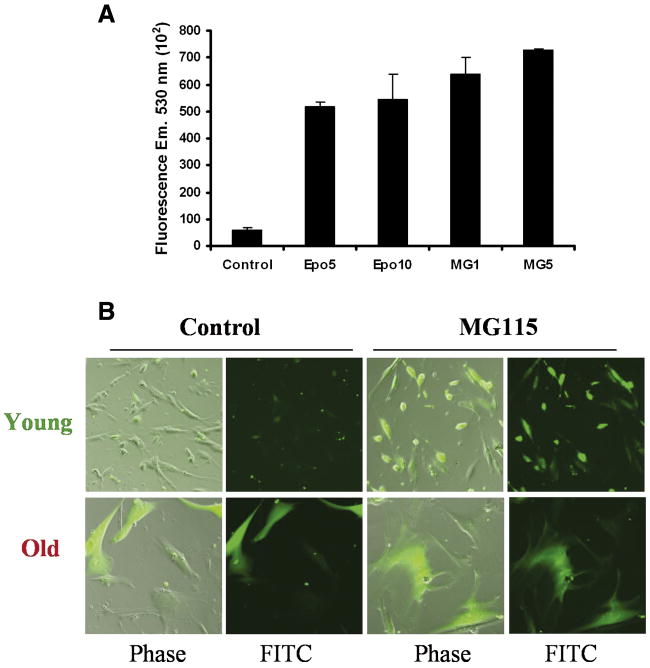

To investigate the role of proteasome inhibition on ROS production we determined ROS and H2O2 levels after proteasome inhibition and during replicative senescence. Intracellular ROS production was evaluated by using 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), a non-fluorescent and non-polar probe that crosses cell membranes. DCFH-DA is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases to non-fluorescent DCFH, which is oxidized to dichlorofluorescein (DCF) by ROS. A previous report has indicated that the fluorescence emitted by DCF at 530 nm varies linearly in respond to increases in concentration of H2O2 (between 0.1 and 1 mM) [44]. Figure 2A shows that incubation of fibroblasts with the proteasome inhibitors epoxomicin or MG115 induces a dramatic increase in intracellular ROS compared to untreated controls, even at the lowest concentration of both inhibitors. Similarly, increase in ROS was also observed in live cells after proteasome inhibition. Figure 2B (top panels) shows increase in fluorescence in early passage cells after 24 hr treatment with 1 μM MG115 compared to untreated controls. Late-passage cells showed a significant increase in fluorescence even in the absence of the inhibitor, suggesting a dysregulation of the pathways that modulate ROS production during cellular senescence. Interestingly, the treatment with MG115 did not generate a significant additional increase in fluorescence, indicating that proteasome inhibition plays an important role in ROS generation during replicative senescence (Figure 2B, bottom panels).

Fig. 2. Effect of proteasome inhibition and replicative senescence on intracellular ROS levels.

(A). Quantitation of ROS production (DCF fluorescence). Fluorescence at 530 nm was determined in cells lysates from young fibroblasts cultured 24 h in the absence (control) or the presence of 5 and 10 nM epoxomicin (Epo) or 1 and 5 μM MG115 (MG). Fluorescence was determined as indicated in Materials and Methods by incubating cells with DCFH-DA. (B). Detection of ROS production in life cells. Young and old cells were incubated by 24 hours in the absence (control) or presence of 1 μM MG115. Cells were incubated with DCFH-DA as indicated in Materials and Methods, and finally observed under fluorescent microscope using FITC filter, or under light microscopy (phase) to show total cells.

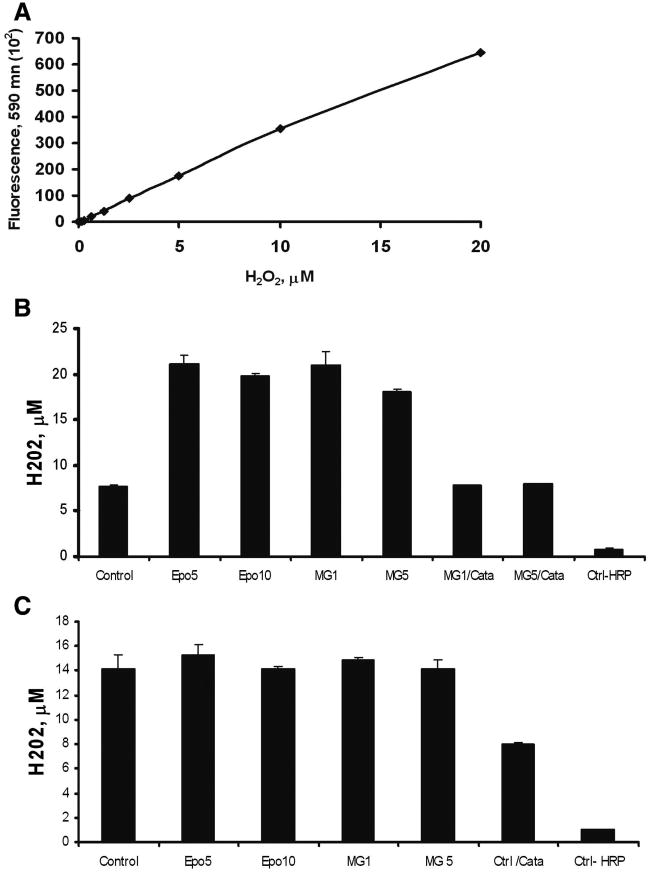

To evaluate the role of proteasome inhibition and replicative senescence on the oxidative status of the extracellular milieu we measured the levels of H2O2. Since H2O2 is membrane-diffusible and more stable than other oxidants, it is possible determining its secreted levels. Extracellular H2O2 was determined by using N-acetyl-3, 7-dihydroxyphenoxazine (Amplex® Red) a sensitive and chemically stable fluorogenic compound that upon HRP-catalyzed oxidation by H2O2 becomes 7-hydroxy-3H-phenoxazine-3-one (resorufin) a highly fluorescent probe that can be detected fluorometrically at 590 nm [46]. The results in figure 3A indicate that fluorescence emitted by resorufin at 590 nm varies linearly in respond to the concentration of H2O2 (range 0–20 μM). Treatment of early-passage fibroblasts with epoxomicin or MG115 induced a significant increase (p< 0.0019) in fluorescence at 590 nm that appears to be due specifically to the presence of extracellular H2O2 since it was drastically inhibited by the presence of catalase in the reaction media (Figure 3B). In addition, the reaction was completely inhibited in the absence of HRP indicating that HRP in the medium is most likely the main peroxidase involved in the reaction without the interference of endogenous peroxidases in the assay. Similar determinations in late-passage cells indicated that at difference of young cells, old fibroblasts have significant increase in basal levels of secreted H2O2, which do not show further increase after proteasome inhibition (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3. Effect of proteasome inhibition and replicative senescence on H2O2 secretion.

(A) H2O2 calibration curve. Early (B) and late-passage (C) cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated 2 hr with 100 μL of reaction mixture containing 50 μM Amplex® Red and 0.1 U/mL HRP in absence or presence of 5 and 10 nM epoxomicin (Epo) or 1 and 5 μM MG115 (MG). The plates were read at 590 nm (Ex: 530, Em: 590nm) in a Synergy HT Multi-Detection microplate reader. MG1/Cata; MG5/Cata: controls with 1,000 U/mL catalase final in the reaction mixture, containing 1 μM or 5 μM MG115 respectively. Ctrl-HRP: control with no HPR in the reaction mixture. Ctrl/Cata: control with 1,000 U/mL catalase final in the reaction mixture containing no proteasome inhibitors.

These results indicate that both proteasome inhibition and cell senescence trigger intracellular ROS and extracellular secretion of H2O2. The results also suggest that proteasome inhibition is responsible for intra and extracellular ROS production during replicative senescence.

Proteasome and the control of mitochondrial function

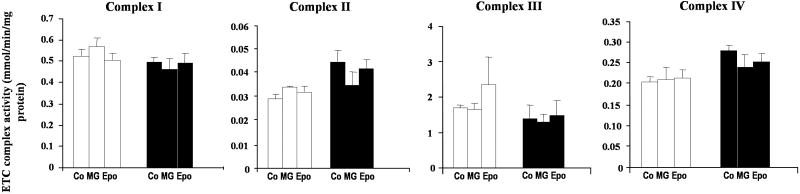

To determine if the increased level of ROS observed as a consequence of proteasome inhibition or replicative senescence alters mitochondrial function, we measured the activity of mitochondrial complexes in purified mitochondria from early-passage cells cultured in the absence or after 24 h incubation of proteasome inhibitors MG115 and epoxomicin. In addition, we also measured the activities of mitochondrial complexes IV (cytochrome c oxidase), and V (ATPase) during replicative senescence. The data indicate that proteasome inhibition induces a general functional impairment in mitochondrial complexes with the exception of complex IV where Epoxomicin showed a modest effect (Figure 4A). Complexes I and III showed approximately 50% of inhibition in response to both concentrations of epoxomicin, and comparatively a higher and dose-dependent effect of MG115. Complexes II, and V, showed a dose-dependent effect by both inhibitors.

Fig. 4. Effect of proteasome inhibition on electron transport chain complexes.

Mitochondria were purified from early-passage cells previously cultured 24 h in the absence (control) or the presence of 5 and 10 nM epoxomicin (Epo) or 1 and 5 μM MG115 (MG). (A) Effects on activity. The activities of the electron transport complexes were measured in purified mitochondria as indicated in Materials and Methods. (B) Effects on protein levels. Protein levels of ETC subunits for complexes I–V were determined by Western blotting of the mitochondrial fraction. Thirty μg of total proteins were analyzed by using specific monoclonal antibodies against: Complex I: 20 kDa subunit; Complex II: 30 kDa subunit; Complex III: Core II subunit; Complex IV: IV subunit; Complex V: ATPase β subunit.

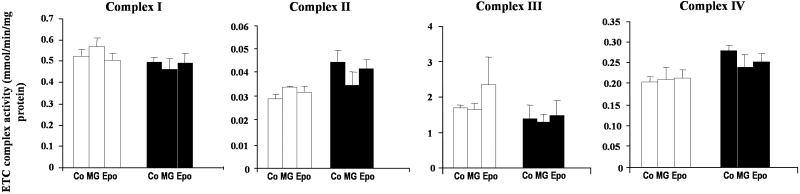

To asses if the inhibition of the proteasome has any affect on the protein levels of each of the complexes, we measured the protein levels of ETC complexes by Western blot using specific antibodies against representative subunits of each complex. In Figure 4B, we showed that the treatment with proteasome inhibitors epoxomicin and MG115 have no effect on the ETC protein levels, including mitochondrial encoded subunits (20 kDa subunit for complex I) or nuclear encoded subunits (30 kDa subunit for complex II; Core II subunit for complex III; subunit IV for complex IV; and ATPase β subunit for complex V). To investigate whether the effect of proteasome inhibitors on ETC complexes activity was due to a direct effect on the mitochondria, we measured the ETC complexes activities in isolated mitochondria treated with 10 nM epoxomicin or 5 μM MG115 for 2 hr at 4 °C or 37 °C. The data in Figure 5 show that proteasome inhibitors do not affect the mitochondrial ETC complexes activities at neither 4 °C nor at 37°C, suggesting that proteasome inhibitors act via proteasome inhibition more than via side effects acting on mitochondria.

Fig. 5. Effect of proteasome inhibition on the activity of electron transport chain in purified mitochondria.

Mitochondria were purified from early-passage cells, and incubated 2 h in the absence (control, Co) or presence of 10 nM epoxomicin (Epo) or 5 μM MG115 (MG). The activities of the electron transport complexes were measured as indicated in Materials and Methods

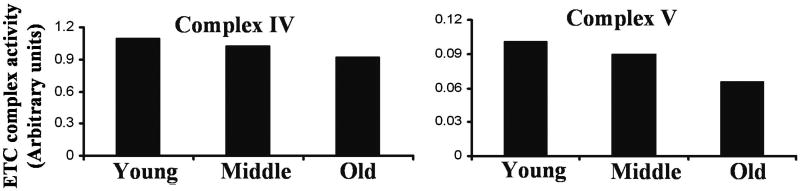

Mitochondrial activity for complexes IV and V showed a similar pattern of inhibition in response to proteasome inhibition during replicative senescence (Figure 6). While Complex IV was slightly decreased in old cells compared to their younger cells, the activity of complex V was inhibited approximately 50% in old cells. These results suggest that proteasome dysfunction during aging alters mitochondrial function which causes up-regulation in ROS levels.

Fig. 6. Effect of replicative senescence on the activity of electron transport chain complexes IV and V.

The activities of electron transport complexes IV and V were determined in purified mitochondria from young, middle and late passage cells. The activities of the electron transport complexes were measured the Blue Native Gel (BN-PAGE) as indicated in Material and Methods.

DISCUSSION

Proteasome inhibition is emerging as a common event in several models of in vitro and in vivo aging and age-related diseases. Since proteasome is involved in a broad range of cellular process, its functional impairment may have severe consequences on cellular homeostasis and survival during aging. Recent reports have suggested a critical role for proteasome in cell viability, cellular senescence and protein oxidative status [31, 47]. A role for proteasome in the control oxidative stress has been confirmed by experiments where the increase in levels of assembled proteasome by overexpression of either the 5 catalytic subunit or the hUMP1/POMP proteasome accessory protein, enhances proteasome-mediated antioxidant defense against several oxidative stressors [48], [49]. In this report, we have studied the mechanisms by which proteasome dysfunction modulates protein oxidation during cellular senescence of human fibroblasts. We have previously suggested that increase in oxidative status of proteins during aging of human fibroblasts may be due to the direct consequence of severe proteasome dysfunction observed in senescent cells [45]. The results presented here suggest that decrease in proteasome function can effectively influence ROS production, and indirectly contribute to increase in protein carbonyl content. Moreover, our data indicate that ROS directly affects proteasome function as indicated by the negative effect on proteasome activity in a process partially reversible by antioxidants (Figure 1). Our results show effects on 20S proteasome after treatment with 200 μM H2O2, however in a lower range of concentrations we have also observed (data not shown) that compared to 20S complex, 26S proteasome is the main complex affected, which agree with previous reports by Grune et al. [50].

Previous studies have shown an inconsistent relation between rate of oxidant generation and pattern of changes in antioxidants defenses in cell cultures established from young and old tissues or during replicative senescence [51], [52] and [53]. Although a small decrease to an insignificant change has been observed in mRNA abundances of gluthathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutases SOD1, SOD2 respectively, their activities were stable during the replicative senescence of WI-38 fibroblasts [53]. However, catalase activity has been reported threefold higher in senescent cells compared to early passage cells which is consistent with the hypothesis that senescence-associated increase in oxidant production stimulate cell to increase their catalase activity. Young cultures increase their GSH concentration in response to oxygen tension however only at ambient oxygen tensions that exceed 35% oxygen this capacity decrease in senescent cells [53]. Consequently, proteasome dysfunction appears as one consistent mechanism linking oxidative stress during replicative senescence of human cells.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is central to aging and studies on structural deterioration, mitochondrial DNA mutations, decreases in the activities of ETC complexes and ATP production, increases in O2 .− and H2O2 generation suggest that mitochondria is highly vulnerable during aging [54, 55, 56, 57]. Our results indicate that partial proteasome inhibition by non-toxic concentrations of inhibitors; significantly affect most mitochondrial complexes activity with the exception of complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) which shows only a modest change even at the highest concentration of epoxomicin or MG115 (Figure 4A). A comparable inhibition pattern is observed for complexes IV and V (ATPase) during replicative senescence (Figure 6) suggesting that proteasome dysfunction in old cells may affect the rate of electron flow through the electron transport chain. The effect of proteasome inhibitors on the activities of ETC complexes and ATP production seems not to be associated with alterations in the protein abundance of representative proteins constituent of the complexes, as indicated by our data showing that proteasome inhibition does not affect the steady state levels of both mitochondrial encoded subunits (20 kDa subunit for complex I) or nuclear encoded subunits (30 kDa subunit for complex II; Core II subunit for complex III; subunit IV for complex IV; and ATPase β subunit for complex V) (Fig. 4B). In addition, although reports have shown in some cancer cells that proteasome inhibitors may cause mitochondrial membrane depolarization, Bax translocation, release of cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO [60, 61, 62, 63, 64]; our results suggest that in human fibroblasts proteasome inhibitors act via proteasome inhibition more than via side effects on mitochondria, since we have observed no effects on the activities of the ETC complexes after the treatment of isolated mitochondria (Figure 5).

In an interesting work Keller et al., have shown that chronic inhibition of proteasome affects the homeostasis of neural mitochondria in a way that resembles age-associated changes, such as increase in production of mitochondrial ROS, dramatic reduction in activity of mitochondrial complexes I and II, increased lipofucsin levels, impaired macroautophagy-induced mitochondrial turnover, and reduced intramitochondrial protein translation [36]. Further studies have shown that proteasome inhibition impaired neuronal protein synthesis, in a process reversible during the first 6 h of treatment, with the neurotoxicity of proteasome inhibition reversible during the first 12 h of treatment [58]. Interestingly this event precedes the increase in ROS and oxidative stress, suggesting that inhibition in protein synthesis by proteasome inhibition may play a role in generating oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. The interaction between proteasome and protein synthesis could have important implications in the differential toxic effects of proteasome inhibitors on different cell types. As proposed in a recent model [58], a short-term proteasome inhibition could induce a consequent short-term decline in protein synthesis, that in some cells could be beneficial to prevent the accumulation of deleterious proteins. In contrast, a long-term proteasome inhibition could lead to an extended inhibition in protein synthesis that could lead to deficient levels of proteins such as heat shock proteins, transcription factors, and other cellular components essentials to maintain cellular homeostasis. The effects of proteasome inhibitors on mitochondrial function could be mediated in part by effects on cytoplasmic/mitochondrial protein synthesis and the time-dependent effects of a short versus long-term exposure. Similarly, this could affect mitochondria homeostasis contributing to the differential toxicity sensitivity to proteasome inhibition. Thus, short-term protein synthesis inhibition could be beneficial to prevent the accumulation of deleterious proteins in the mitochondria. In turn, a long-term effect of proteasome of proteasome inhibition on protein synthesis could affect mitochondria function increasing ROS levels and decreasing ATP production. Depletion in ATP could represent an additional negative feed back factor on energy-dependent process such as chromatin remodeling, transcription, RNA metabolism and ribosome biogenesis; described aspects influenced by the ubiquitin proteasome system [59]. These studies suggest that the interplay between proteasome and protein synthesis could mediate the effects of the progressive age-dependent and long-term proteasome dysfunction on mitochondrial homeostasis observed during cellular senescence, aging in vivo and age-related diseases.

While oxidative damage has been known to cause proteasome dysfunction during aging, our results support proteasome inhibition as mediator of oxidative stress and ROS production by affecting mitochondrial function. In consequence, we support that the proteasome-mitochondria axis could play a major role in mitochondrial dysfunction, increase in ROS production and oxidative stress during cellular senescence. We propose that progressive decrease in proteasome function during aging can promote mitochondrial damage and ROS accumulation, which could affect cellular components including proteasome and mitochondria exacerbating the oxidative stress. Impairments in proteasome function may also severely affect tissue physiology during aging and age-related disease since proteasome inhibition favors H2O2 secretion and the consequent generation of a pro-oxidative condition at the extracellular microenvironment.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Felipe Sierra and Iramoudi Ayene for critical reading of the manuscript, and for their helpful discussions and suggestions.

This study was supported by Grants AG20955-05 and AG20955-05S1, from National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DCFH-DA

2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate

- GSH

Glutathione

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- KRPG

Krebs Ringer Phosphate Glucose

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Suc-LLVY-AMC

N-succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Cristofalo VJ, Volker C, Francis MK, Tresini M. Age-dependent modifications of gene expression in human fibroblasts. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1998;8:43–80. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v8.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cristofalo VJ, Lorenzini A, Allen RG, Torres C, Tresini M. Replicative senescence: a critical review. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:827–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seshadri T, Campisi J. Repression of c-fos transcription and an altered genetic program in senescent human fibroblasts. Science. 1990;247:205–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2104680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara E, Uzman JA, Dimri GP, Nehlin JO, Testori A, Campisi J. The helix-loop-helix protein Id-1 and a retinoblastoma protein binding mutant of SV40 T antigen synergize to reactivate DNA synthesis in senescent human fibroblasts. Dev Genet. 1996;18:161–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)18:2<161::AID-DVG9>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheerin A, Thompson KS, Goyns MH. Altered composition and DNA binding activity of the AP-1 transcription factor during the ageing of human fibroblasts. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1813–24. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tresini M, Lorenzini A, Frisoni L, Allen RG, Cristofalo VJ. Lack of Elk-1 phosphorylation and dysregulation of the extracellular regulated kinase signaling pathway in senescent human fibroblast. Exp Cell Res. 2001;269:287–300. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres C, Francis MK, Lorenzini A, Tresini M, Cristofalo VJ. Metabolic stabilization of MAP kinase phosphatase-2 in senescence of human fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tresini M, Lorenzini A, Torres C, Cristofalo V. Modulation of replicative senescence of diploid human cells by nuclear ERK signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4136–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka K, Ii K, Ichihara A, Waxman L, Goldberg AL. A high molecular weight protease in the cytosol of rat liver. I. Purification, enzymological properties, and tissue distribution. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grune T, Reinheckel T, Davies KJ. Degradation of oxidized proteins in mammalian cells. Faseb J. 1997;11:526–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin, proteasomes, and the regulation of intracellular protein degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:215–23. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poppek D, Grune T. Proteasomal defense of oxidative protein modifications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:173–84. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding Q, Dimayuga E, Keller JN. Proteasome regulation of oxidative stress in aging and age-related diseases of the CNS. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:163–72. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Squier TC. Redox Modulation of Cellular Metabolism Through Targeted Degradation of Signaling Proteins by the Proteasome. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2006;8:217–228. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farout L, Friguet B. Proteasome Function in Aging and Oxidative Stress: Implications in Protein Maintenance Failure. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2006;8:205–216. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King RW, Deshaies RJ, Peters JM, Kirschner MW. How proteolysis drives the cell cycle. Science. 1996;274:1652–9. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muratani M, Tansey WP. How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrm1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naujokat C, Hoffmann S. Role and function of the 26S proteasome in proliferation and apoptosis. Lab Invest. 2002;82:965–80. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000022226.23741.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilt W, Wolf DH. Proteasomes: destruction as a programme. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehner PJ, Cresswell P. Processing and delivery of peptides presented by MHC class I molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulombe P, Rodier G, Pelletier S, Pellerin J, Meloche S. Rapid turnover of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 3 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway defines a novel paradigm of mitogen-activated protein kinase regulation during cellular differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4542–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.13.4542-4558.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu Z, Xu S, Joazeiro C, Cobb MH, Hunter T. The PHD domain of MEKK1 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and mediates ubiquitination and degradation of ERK1/2. Mol Cell. 2002;9:945–56. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulteau AL, Petropoulos I, Friguet B. Age-related alterations of proteasome structure and function in aging epidermis. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:767–77. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponnappan U. Ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is compromised in CD45RO+ and CD45RA+ T lymphocyte subsets during aging. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:359–67. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulteau AL, Szweda LI, Friguet B. Age-dependent declines in proteasome activity in the heart. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;397:298–304. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husom AD, Peters EA, Kolling EA, Fugere NA, Thompson LV, Ferrington DA. Altered proteasome function and subunit composition in aged muscle. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;421:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louie JL, Kapphahn RJ, Ferrington DA. Proteasome function and protein oxidation in the aged retina. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75:271–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller JN, Hanni KB, Markesbery WR. Possible involvement of proteasome inhibition in aging: implications for oxidative stress. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;113:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(99)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petropoulos I, Conconi M, Wang X, Hoenel B, Bregegere F, Milner Y, Friguet B. Increase of oxidatively modified protein is associated with a decrease of proteasome activity and content in aging epidermal cells. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:B220–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.5.b220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sitte N, Merker K, von Zglinicki T, Grune T. Protein oxidation and degradation during proliferative senescence of human MRC-5 fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:701–8. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chondrogianni N, Stratford FL, Trougakos IP, Friguet B, Rivett AJ, Gonos ES. Central role of the proteasome in senescence and survival of human fibroblasts: induction of a senescence-like phenotype upon its inhibition and resistance to stress upon its activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28026–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres C, Lewis L, Cristofalo VJ. Proteasome inhibitors shorten replicative life span and induce a senescent-like phenotype of human fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:845–53. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanz A, Pamplona R, Barja G. Is the mitochondrial free radical theory of aging intact? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:582–99. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shigenaga M, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10771–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan PG, Dragicevic NB, Deng JH, Bai Y, Dimayuga E, Ding Q, Chen Q, Bruce-Keller AJ, Keller JN. Proteasome inhibition alters neural mitochondrial homeostasis and mitochondria turnover. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20699–707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cristofalo VJ, Charpentier R. A standard procedure for cultivating human diploid fibroblast like cells to study cellular aging. J Tissue Cult Methods. 1980;6:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9363–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schagger H vJG. Blue native electrophoresis for isolation of membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form. Anal Biochem. 1991;199:223–31. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90094-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwong LK, Sohal RS. Age-related changes in activities of mitochondrial electron transport complexes in various tissues of the mouse. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;373:16–22. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansouri A, Muller FL, Liu Y, Ng R, Faulkner J, Hamilton M, Richardson A, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Van Remmen H. Alterations in mitochondrial function, hydrogen peroxide release and oxidative damage in mouse hind-limb skeletal muscle during aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birch-Machin MA TD. Assaying mitochondrial respiratory complex activity in mitochondria isolated from human cells and tissues. Methods Cell Biol. 2001;65:97–117. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(01)65006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boveris A, Cadenas E. Mitochondrial production of superoxide anions and its relationship to the antimycin insensitive respiration. FEBS Lett. 1975;54:311–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80928-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:612–6. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torres C, Lewis L, Cristofalo VJ. Proteasome inhibitors shorten replicative life span and induce a senescent-like phenotype of human fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:845–53. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohanty JG, Jaffe JS, Schulman ES, Raible DG. A highly sensitive fluorescent micro-assay of H2O2 release from activated human leukocytes using a dihydroxyphenoxazine derivative. J Immunol Methods. 1997;202:133–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chondrogianni N, Gonos ES. Proteasome inhibition induces a senescence-like phenotype in primary human fibroblasts cultures. Biogerontology. 2004;5:55–61. doi: 10.1023/b:bgen.0000017687.55667.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chondrogianni N, Tzavelas C, Pemberton AJ, Nezis IP, Rivett AJ, Gonos ES. Overexpression of proteasome beta5 assembled subunit increases the amount of proteasome and confers ameliorated response to oxidative stress and higher survival rates. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11840–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chondrogianni N, Gonos ES. Overexpression of hUMP1/POMP proteasome accessory protein enhances proteasome-mediated antioxidant defence. Exp Gerontol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.01.012. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reinheckel T, Sitte N, Ullrich O, Kuckelkorn U, Davies KJ, Grune T. Comparative resistance of the 20S and 26S proteasome to oxidative stress. Biochem J. 1998;335:637–42. doi: 10.1042/bj3350637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allen RG, Keogh BP, Gerhard G, Pignolo R, Horton J, Cristofalo VJ. Expression and regulation of SOD activity in human skin fibroblasts from donors of different ages. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1995;165:576–587. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allen RG, Keogh BP, Tresini M, Gerhard GS, Volker C, Pignolo RJ, Horton J, Cristofalo VJ. Development and age-associated differences in electron transport potential and consequences for oxidant generation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24805–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allen RG, Tresini M, Keogh BP, Doggett DL, Cristofalo VJ. Differences in electron transport potential, antioxidant defenses, and oxidant generation in young and senescent fetal lung fibroblasts (WI- 38) J Cell Physiol. 1999;180:114–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199907)180:1<114::AID-JCP13>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Terman A, Dalen H, Eaton JW, Neuzil J, Brunk UT. Mitochondrial recycling and aging of cardiac myocytes: the role of autophagocytosis. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:863–76. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cadenas E, Davies KJ. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29 doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sohal RS, Sohal BH. Hydrogen peroxide release by mitochondria increases during aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 1991;57:187–202. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90034-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chomyn A, Attardi G. MtDNA mutations in aging and apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:519–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding Q, Dimayuga E, Markesbery WR, Keller JN. Proteasome inhibition induces reversible impairments in protein synthesis. FASEB J. 2006;20:1055–63. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5495com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ding Q, Cecarini V, Keller JN. Interplay between protein synthesis and degradation in the CNS: physiological and pathological implications. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Papa L, Gomes E, Rockwell P. Reactive oxygen species induced by proteasome inhibition in neuronal cells mediate mitochondrial dysfunction and a caspase-independent cell death. Apoptosis. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0069-5. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pérez-Galán P, Roué G, Villamor N, Montserrat E, Campo E, Colomer D. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib induces apoptosis in mantle-cell lymphoma through generation of ROS and Noxa activation independent of p53 status. Blood. 2006;107:257–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling YH, Liebes L, Zou Y, Perez-Soler R. Reactive oxygen species generation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the apoptotic response to Bortezomib, a novel proteasome inhibitor, in human H460 non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33714–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagy K, Székely-Szüts K, Izeradjene K, Douglas L, Tillman M, Barti-Juhász H, Dominici M, Spano C, Luca Cervo G, Conte P, Houghton JA, Mihalik R, Kopper L, Peták I. Proteasome inhibitors sensitize colon carcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via enhanced release of Smac/DIABLO from the mitochondria. Pathol Oncol Res. 2006;12:133–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02893359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saulle E, Petronelli A, Pasquini L, Petrucci E, Mariani G, Biffoni M, Ferretti G, Scambia G, Benedetti-Panici P, Cognetti F, Humphreys R, Peschle C, Testa U. Proteasome inhibitors sensitize ovarian cancer cells to TRAIL induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:635–55. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]