Abstract

In recent years, intense research efforts have been dedicated to elucidating the pathogenic mechanisms of HIV-associated disease progression. In addition to the progressive depletion and dysfunction of CD4+ T cells, HIV infection also leads to extensive defects in the humoral arm of the immune system. The lack of immune control of the virus in almost all infected individuals is a great impediment to the treatment of HIV-associated disease and to the development of a successful HIV vaccine. This Review focuses on advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of B-cell dysfunction in HIV-associated disease and discusses similarities with other diseases that are associated with B-cell dysfunction.

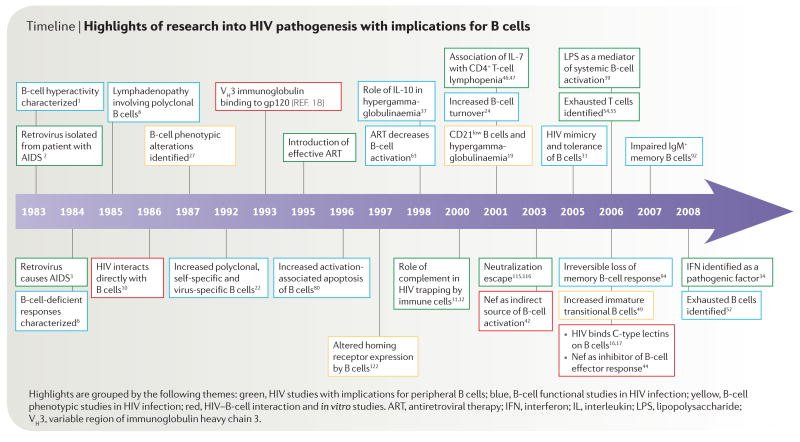

In 1983, a study was published describing B-cell hyper-activation and dysfunction in individuals with AIDS1. Just months before, a T-cell lymphotropic virus had been isolated from the lymph node of a patient ‘at risk’ of AIDS2. The following year, the aetiological connection between this virus and AIDS was firmly established3. The observation of hyperactivation of immune cells1 in a disease that is characterized by immune deficiency captured the essence of the aberrant immune activation that has come to define HIV-induced immunopathogenesis, not only related to B cells but also to other components of the immune system. Over the course of its history, HIV-associated disease has been the subject of intense research and debate, in particular regarding the underlying causes of progressive CD4+ T-cell depletion and loss of immune function (TIMELINE). One prevailing hypothesis is that in most untreated individuals, HIV infection leads to chronic immune activation through mechanisms that are largely related to the systemic indirect effects (generally referred to as bystander effects) of ongoing HIV replication4,5. Such bystander effects have been described for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as for natural killer (NK) cells and B cells. This Review focuses mainly on the B-cell dysregulation that arises during HIV infection and describes how changes in B-cell physiology and function are affected by the suppression of plasma viraemia through combination antiretroviral therapy (ART). Recent interest in refocusing efforts on antibody-based HIV vaccines provides a timely opportunity to review our current understanding of the mechanisms of B-cell pathogenesis in HIV-associated disease. Although a comprehensive analysis of the antibody response to HIV is beyond the scope of this Review, salient features of B-cell responses against HIV in infected individuals are discussed in BOX 1 and potential reasons to explain the poorly effective antibody responses against the virus are listed in TABLE 1.

Timeline.

Highlights of research into HIV pathogenesis with implications for B cells

Box 1. B-cell responses against HIV.

An effective antibody response against HIV is likely to be thwarted by the numerous B-cell abnormalities that arise during HIV-associated disease. In addition, impediments to HIV-specific antibody responses that relate to the virus itself probably contribute to the defect (TABLE 1). It is currently unclear which, if any, of these antibody-related factors contribute to the lack of control of HIV replication, and conflicting results from B-cell-depleting experiments in SIV infection have not clarified whether antibodies can restrict virus replication113,114. It is also unclear whether fully functional B cells can restrict the virus in spite of the antibody escape and other evasion mechanisms of HIV. As several reports have shown, the antibody response to HIV following infection is clearly ineffective, with the early response being largely directed against non-neutralizing epitopes of the HIV envelope and later B-cell responses lagging behind a rapidly diversifying virus115,116. In addition, the HIV-specific IgA response at mucosal sites, where HIV transmission mainly occurs and where HIV preferentially replicates40, is low when compared with other classes of immunoglobulin117,118. Although there is no clear explanation for the paucity of HIV-specific IgA responses during HIV infection, the early destruction of organized lymphoid tissues in the intestinal mucosa and the inhibition of class switching by the HIV protein Nef have been proposed as potential reasons44. Furthermore, there is renewed interest in exploring the innate immune responses to HIV infection as a way of preventing systemic dissemination of the virus while the adaptive arm of the immune response is generated119. In terms of humoral immunity, the innate immune response mainly consists of natural antibodies that are produced by marginal zone B cells120. If the suggestion that IgM+ memory B cells in the peripheral blood are related to marginal zone B cells in the spleen is correct (see main text), then this presents another impediment to mounting a successful innate immune response to HIV given the recently described defects of IgM+ memory B cells in HIV-infected individuals83,89,92.

Table 1.

Factors contributing to the ineffective antibody response against HIV in infected individuals

| Impediment | Consequence | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| High degree of HIV diversity | Challenge for vaccine-induced immunity | 121 |

| Poor immunological access to conserved HIV Env regions | Few broadly reactive neutralizing antibodies | 121 |

| Delay in neutralizing antibody response | Virus dissemination | 115,116 |

| Rapid viral mutation rate and selection pressure | Virus escape | 115,116 |

| Paucity of virus-specific IgAs at mucosal sites | Virus dissemination | 117,118 |

| Polyclonal activation | Few specific antibodies of low specificity; few memory B cells | 1,22,23,63 |

| Natural antibodies cross-react with self antigens | Tolerance | 31 |

| Functional exhaustion of B cells | Few specific antibodies of low specificity | 52 |

| Paucity of IgM+ memory B cells | Decreased natural immunity | 92 |

| Interference by Nef | Suppressed class switching | 44 |

Env, envelope protein.

As with many other areas of the immunopathogenesis of HIV-associated disease, insights into B-cell dysfunction have progressed rapidly since the availability of combination ART, which has been extremely effective in decreasing HIV viraemia to below detectable levels in a high percentage of properly treated individuals. Before the era of effective ART, B-cell hyperactivation and poorly inducible antibody responses were widely reported in HIV-infected individuals1,6–9. Since the introduction of effective combination ART in the mid 1990s, it has become possible to delineate the immune defects associated with HIV infection that are related to ongoing viral replication as opposed to the defects that remain despite the suppression of detectable viraemia. In addition, combination ART has allowed us to examine more clearly the potential mechanisms of immune dysfunction and immunopathogenesis in individuals who are infected with HIV.

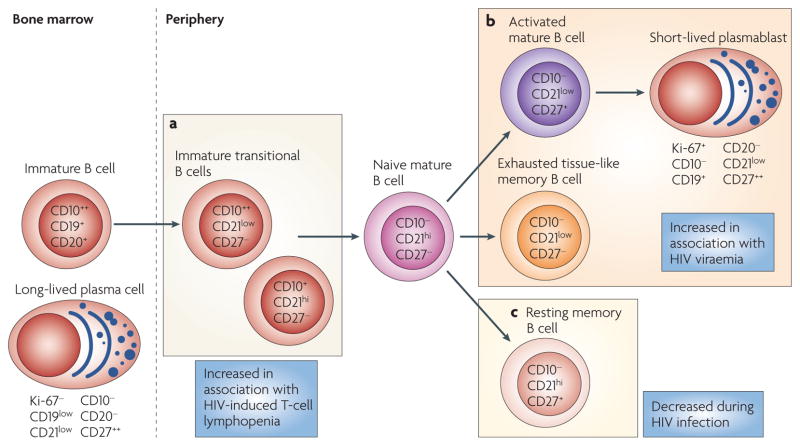

The scope of HIV-induced B-cell defects can be best appreciated by first considering the various human B-cell subpopulations that circulate in the peripheral blood, from which most observations of HIV-induced defects have been made. In healthy individuals, most B cells in the peripheral blood are either resting naive B cells or memory B cells that express either switched or unswitched antibody isotypes (IgG, IgE and IgA, or IgM and IgD, respectively). In HIV-infected individuals, several additional B-cell subpopulations (which are not normally present to any substantial degree in the peripheral blood of uninfected individuals) can make up considerable fractions of the total B-cell population in the peripheral blood. These include immature transitional B cells, exhausted B cells, activated mature B cells and plasmablasts (FIG. 1). As discussed in this Review, many of the B-cell defects that have been described in HIV-associated disease can be attributed to the expansion or contraction of one or several of these B-cell subpopulations. Such alterations, together with the immune evasion mechanisms of the virus, help to explain the deficiencies in antibody responses against HIV and other pathogens in HIV-infected individuals.

Figure 1. HIV-induced alterations of human B-cell subpopulations.

As immature CD19+CD20+ B cells exit the bone marrow, a small fraction can be identified in the peripheral blood by the expression of CD10 in the absence of CD27. The frequency of these immature transitional B cells, which can be further divided into CD21low and CD21hi subsets, is increased in the peripheral blood of HIV-infected individuals, probably as a result of the increased serum levels of interleukin-7 (IL-7) that are associated with HIV-induced CD4+ T-cell lymphopenia (a). Chronic HIV viraemia is associated with the expansion of several B-cell subpopulations, including activated mature B cells that have downregulated their expression of CD21 and express CD27, short-lived Ki-67+ plasmablasts that have downregulated their expression of CD20 and CD21 and express high levels of CD27, and tissue-like memory B cells that have downregulated their expression of CD21, do not express CD27 and have several features of virus-induced exhaustion (listed in FIG. 3) (b). HIV infection is associated with a loss of resting memory B cells (defined by the expression of CD21 and CD27) that is not reversed by antiretroviral therapy (c).

Direct effects of HIV viraemia on B cells

HIV infection results in persistent viral replication, leading to variable levels of detectable plasma viraemia in most individuals who do not receive effective ART. The effects of ongoing HIV replication on B cells are thought to reflect a combination of direct interactions of B cells with the virus, as discussed in this section, and indirect interactions that are associated with a wide range of systemic alterations, which are discussed in the following section.

Direct interactions between HIV and B cells were first reported several years ago10, although there is little evidence that HIV can productively replicate in B cells in vivo. There is, however, strong evidence that HIV binds to B cells in vivo through interactions between the complement receptor CD21 (also known as CR2), which is expressed on most mature B cells, and complement proteins bound to HIV virions that are circulating in vivo11,12 (FIG. 2). Such immune-complex-based interactions might provide stimulatory signals to B cells, although the low frequency of B cells directly interacting with HIV virions would predict that this is a minor activating pathway12. It is more probable that through this interaction, B cells facilitate cell-to-cell transmission of HIV13. A similar mechanism of HIV interaction has been suggested for follicular dendritic cells (FDCs)14, which also express CD21 and might function as a long-lived extracellular reservoir for HIV even in the presence of effective ART15.

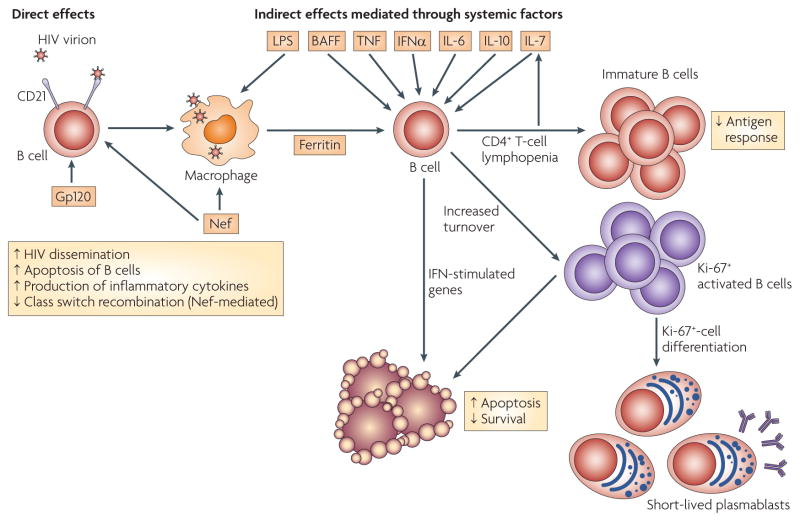

Figure 2. Direct and indirect effects of HIV replication on B cells.

Direct effects of HIV virions or viral proteins on B cells include the binding of complement-bound HIV virions to B cells through the complement receptor CD21, which can enhance virus dissemination and increase B-cell depletion by apoptosis. Binding of HIV virions or gp120 can also induce B cells to secrete inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin -6 (IL-6). In addition, secreted Nef from sites of HIV replication can diffuse into B cells and suppress B-cell class switch recombination. Moreover, HIV-infected macrophages release factors, some of which are secreted in a Nef-dependent mechanism (such as ferritin), that stimulate B cells. Indirect effects of ongoing HIV replication in infected individuals are the result of HIV-induced immune-cell activation and CD4+ T-cell depletion. Increased serum levels of IL-7 are associated with CD4+ T-cell lymphopenia, increased B-cell immaturity and decreased responses to antigen. Various systemic mediators of immune-cell activation and increased cell turnover have been proposed, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), B-cell-activating factor (BAFF), TNF, interferon-α (IFNα), IL-6 and IL-10. IFN-stimulated genes are strongly induced in B cells of HIV-viraemic individuals, probably as a result of chronic immune-cell activation. LPS is released as a result of microbial leakage from HIV-induced intestinal tissue damage (not shown). Serum levels of BAFF are increased in HIV infection, although the source of increased secretion is unknown.

Additional potential HIV-binding receptors have been identified on B cells, including DC-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN), other C-type lectin receptors16,17 and surface immunoglobulins of the variable heavy chain 3 (VH3) family18. Although evidence from in vitro models16,17 and from analyses of VH3-family immunoglobulin-expressing B cells18 suggests that these interactions directly mediate the effects of HIV on B cells, direct in vivo evidence for such effects is lacking. Furthermore, the low frequency of B cells carrying HIV virions on their cell surface compared with the magnitude of B-cell dys-regulation in HIV-viraemic individuals indicates that other indirect mechanisms of B-cell immunopathogenesis exist (FIG. 2). In this regard, similar arguments have been made for CD4+ T cells, as the frequency of infected CD4+ T cells is insufficient to account for their progressive loss and dysfunction4.

Indirect effects of HIV viraemia on B cells

HIV-induced B-cell hyperactivity

HIV-induced immune-cell activation is one of the few widely accepted hallmarks of HIV pathogenesis and disease progression. The hyperactivation of B cells by HIV is characterized by several features: hypergammaglobulinaemia1,19–21; increased polyclonal B-cell activation1,19,22; increased cell turnover23,24; increased expression of activation markers, including CD70, CD71 (also known as TFRC), CD80 and CD86 (REFS 25–28); an increase in the differentiation of B cells to plasmablasts as measured by phenotypical (FIG. 1), functional and morphological measures19,23,29,30; increased production of autoantibodies22,31,32; and an increase in the frequency of B-cell malignancies33.

The factors that contribute to HIV-viraemia-induced immune-cell hyperactivation in vivo remain largely unknown, but are a matter of intense research and debate. Several cytokines and growth factors have been suggested to directly or indirectly trigger the activation of B cells in HIV-viraemic individuals, including interferon-α (IFNα)34, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)35, interleukin-6 (IL-6)36, IL-10 (REF. 37), CD40 ligand37 and B-cell-activating factor (BAFF; also known as TNFSF13B)17 (FIG. 2). Many of these factors are thought to be associated with B-cell hyperactivation in HIV-viraemic individuals because of their increased serum levels during HIV infection. In the case of IFNα, plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) might be responsible for increased production in chronically HIV-viraemic individuals34,38. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), possibly released into the circulation following intestinal tissue damage owing to large-scale HIV-induced T-cell depletion in the gut, has also been proposed to activate B cells39. However, the mechanism of activation is probably indirect, possibly through the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IFNα40, because human B cells do not express LPS receptors41.

In addition, HIV proteins, including gp120 (REFS 17, 35) and Nef42,43, have been proposed to act as direct or indirect activators of B cells through mechanisms that remain mostly speculative. In the case of gp120, its binding to C-type lectins that are expressed on B cells has been shown to induce immunoglobulin class switching and increased expression of the immunoglobulin class-switching enzyme activation-induced cytidine deaminase17. In the case of Nef, the effects on B cells might be divergent. On the one hand, Nef has been shown to accumulate in B cells and to inhibit immunoglobulin class switching by interfering with CD40-ligand-mediated signalling44. On the other hand, Nef can indirectly promote polyclonal B-cell activation and increase CD4+ T-cell permissiveness to infection with HIV by inducing macrophages to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines42 (FIG. 2). However, these initial studies were largely based on in vitro observations, and further investigation is required to determine their in vivo relevance. In this regard, the polyclonal B-cell-activating properties of Nef were recently correlated with HIV-induced B-cell alterations in infected individuals43. Specifically, HIV-infected macrophages were shown to secrete the acute phase protein ferritin through a Nef-dependent mechanism, and direct correlations were found between the extent of hypergammaglobulinaemia, levels of ferritin in the plasma and HIV viral load. As is discussed in detail below, there is also growing evidence to suggest that IFNα and type I IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) might have a role in the HIV-viraemia-induced immune-cell hyperactivation23,34,45.

Taken together, these studies have identified several potential modulators of B-cell hyperactivation that are induced by ongoing HIV replication. In addition, B cells activated by HIV viraemia can themselves potentiate immune activation of other cells, either by cell–cell interactions (which are favoured by the increased expression of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86 by B cells)25–28 or by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF35.

HIV-induced lymphopenia

In most untreated individuals, HIV infection leads to the progressive loss of CD4+ T cells. Several years ago, expression of the T-cell homeostatic cytokine IL-7 was shown to be dys-regulated in HIV-infected individuals with advancing HIV-associated disease; increased serum levels of IL-7 were linked to decreased numbers of CD4+ T cells46,47. Although IL-7 is not absolutely essential for human B-cell development, it can induce the proliferation of human B-cell precursors48. Indeed, we have shown that high serum levels of IL-7 directly correlated with increased frequencies of immature transitional B cells in the peripheral blood of HIV-infected individuals (FIG. 1). These, in turn, directly correlated with HIV plasma viraemia and inversely correlated with CD4+ T-cell numbers49. High viral load and low CD4+ T-cell counts are thus associated with increased serum levels of IL-7 and increased numbers of immature transitional B cells (FIG. 2). A similar association between increased serum levels of IL-7, B-cell immaturity and decreased CD4+ T-cell counts was observed in patients with non-HIV-related idiopathic CD4+ T-cell lymphocytopenia (ICL), which suggests that HIV-induced CD4+ T-cell lymphopenia (and not HIV viraemia itself) drives the expansion of immature transitional B cells in HIV-infected individuals50. So, as first reported several years ago27, there is evidence of an increase both in B-cell activation and in the frequency of immature B cells in HIV-infected individuals.

HIV-associated B-cell exhaustion

The loss of CD21 expression on peripheral blood B cells is a reliable marker of ongoing HIV replication and disease progression51. CD21low B cells constitute a heterogeneous population of cells in HIV-infected individuals (FIG. 1); one fraction of the CD21low B-cell compartment is made up of CD27+ B cells that have undergone HIV-induced activation and differentiation to plasmablasts19 and another fraction is made up of immature transitional CD10+ B cells that are over-represented as a result of HIV-induced T-cell lymphopenia49. However, a large proportion of CD21low B cells in HIV-viraemic individuals does not fit into either of these fractions, and we now believe that these B cells constitute an exhausted B-cell subpopulation52 (FIG. 3). The term exhaustion — which was first used to describe T cells in the rodent model of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection53 and later in HIV infection in humans54,55 — refers to virus-specific immune cells that have lost function because of the chronic nature of the viral infection. Phenotypically, these cells express high levels of inhibitory receptors such as programmed cell death 1 (PD1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4)54–56. The discovery of a subpopulation of memory B cells in human tonsils57 that expresses the putative inhibitory receptor Fc-receptor-like 4 (FCRL4), high levels of CD20, low levels of CD21 and the classic marker of B-cell memory, CD27, provided us with a starting point to characterize the previously unidentified CD21low B cells that are present in the peripheral blood of HIV-viraemic individuals, which we reasoned might be related to this FCRL4+ memory B-cell population in the tonsils. In support of this possibility, increased expression of FCRL4 by peripheral-blood-derived mature B cells of HIV-viraemic, but not HIV-aviraemic or HIV-negative, individuals has been observed52. Furthermore, the expression of FCRL4 was enriched on a subpopulation of B cells in HIV-viraemic individuals that also expressed decreased levels of CD21 and CD27 and increased levels of CD20, when compared with CD27+ B cells and CD21hiCD27− naive B cells52. Of note, the tonsil-tissue-derived memory B cells were defined by the expression of FCRL4 and were not necessarily negative for CD21 and CD27 (REFS 57,58), whereas their counterparts in the peripheral blood of HIV-viraemic individuals were more precisely defined as CD21lowCD27−; accordingly, we named them tissue-like memory B cells52.

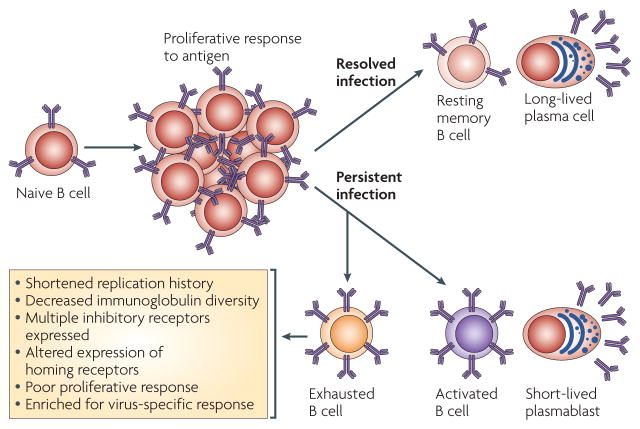

Figure 3. B-cell exhaustion induced by persistent HIV infection and ongoing viral replication.

In the context of self-limiting viral infections, naive B cells respond to exogenous antigen by migrating to T-cell-rich areas of lymphoid tissues, becoming activated, initiating a germinal centre reaction that selects for B cells with improved antigen binding and finally exiting the germinal centre as either long-lived resting memory B cells or plasma cells. In the context of a persistent viral infection such as HIV, chronic immune activation increases the frequency of antigen-experienced B cells that are short-lived and have undergone several cell divisions. The chronic immune activation induced by HIV also gives rise to exhausted B cells that have a shortened replication history and decreased immunoglobulin diversity, consistent with the increased expression of multiple inhibitory receptors and altered expression of homing receptors that favour migration to sites of inflammation and away from sites of cognate B-cell–T-cell interactions. The exhausted B cells have poor proliferative responses, but are enriched for virus-specific responses.

FCRL4 was not the only putative inhibitory receptor that was associated with these tissue-like memory B cells in peripheral blood. High levels of many B-cell inhibitory receptors, including CD22, CD72, leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 1, CD85j (also known as LILRB1 and ILT2) and CD85k (also known as LILRB4 and ILT3), were expressed by tissue-like memory B cells from HIV-viraemic individuals52. A similar increase in the expression of many inhibitory receptors is a signature feature of persistent-virus-induced T-cell exhaustion, which provides further indication that tissue-like memory B cells could be an exhausted B-cell counterpart59.

In addition to the expression of inhibitory receptors, tissue-like memory B cells and virus-exhausted T cells have similar alterations in their expression of homing receptors and adhesion molecules. Specifically, tissue-like memory B cells upregulate their expression of CXC-chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) and CD11c, which are required for migration to sites of inflammation, and downregulate their expression of CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) and CD62L, which are required for migration to lymph nodes52,59. Tissue-like memory B cells also express decreased levels of CXCR4 and CXCR5, two chemokine receptors that are crucial for B-cell trafficking to germinal centres, where the maturation of T-cell-dependent B-cell responses occurs60. The decreased surface expression of CXCR5 by B cells from HIV-viraemic individuals might be due to ligand-mediated internalization of CXCR5 resulting from overexpression of its ligand, CXC-chemokine ligand 13 (CXCL13), as measured in the serum61.

Virus-specific T-cell exhaustion is characterized by functional defects that are manifested by the incremental loss of proliferative and effector properties62. Similarly, tissue-like memory B cells have decreased proliferative capacity and effector function, as measured by decreased immunoglobulin diversification, when compared with CD27+ B cells52. Furthermore, tissue-like memory B cells have also undergone fewer cell divisions in vivo compared with CD27+ B cells, possibly as a result of the overexpression of inhibitory receptors that halt further cell division. Finally, although tissue-like memory B cells also have a decreased response to recall antigens ex vivo, this population of cells is enriched for HIV-specific responses, similarly to their exhausted virus-specific T-cell counterparts54–56,59. Taken together, there is strong evidence suggesting that tissue-like memory B cells are an exhausted B-cell subpopulation in the peripheral blood of HIV-viraemic individuals (FIG. 3). As HIV-specific responses are enriched in B cells that show signs of functional exhaustion, such dysregulation might contribute to the inefficiency of the antibody response against HIV in infected individuals. So, chronic HIV viraemia is associated with the expansion of several aberrant B-cell subpopulations, including immature transitional, hyperactivated and exhausted B cells, which collectively are likely to contribute to various facets of B-cell dysfunction.

Impact of effective ART on B-cell abnormalities

The mechanisms of B-cell and generalized immune dysfunction in HIV-infected individuals were difficult to address before the availability of effective ART. The effective decrease of HIV viraemia by ART has not only led to substantial reductions in the morbidity and mortality of individuals infected with HIV, but has also provided opportunities to investigate the causes of HIV-induced immune dysfunction. Since 1996, when combination ART was first used widely in the developed world to effectively suppress HIV viraemia, it has become clear that many of the B-cell abnormalities that are associated with HIV-replication-induced immune-cell activation can be reversed by ART, whereas some deficiencies, particularly in memory B cells, persist even after several years of effective ART.

B-cell defects that are reversed by ART

One of the first studies to address the effects of decreasing HIV viraemia by ART on B-cell responses showed a reversal of several B-cell abnormalities in both acutely and chronically infected individuals after treatment63. The B-cell abnormalities that were decreased by ART included hypergammaglobulinaemia and HIV-specific and HIV-non-specific B-cell responses, as measured by the number of B cells that spontaneously secrete high levels of immunoglobulins. Several studies have since confirmed and extended these findings19,20,64–67. The increased frequency of B cells secreting high levels of immunoglobulins during viraemia was attributed to the expansion of the CD21low B-cell subpopulation in the peripheral blood of HIV-viraemic individuals19. Plasmacytoid morphology and low proliferative potential, both of which are features of B-cell differentiation to plasmablasts, were observed in the CD21low, but not the CD21hi, B-cell fraction of HIV-viraemic individuals. Decreased proliferation of B cells in response to various B-cell stimuli during HIV viraemia has been described in numerous studies and is largely attributed to the over-representation of the aberrant B-cell subpopulations that are associated with ongoing HIV replication (described above)68,69. Finally, the increased expression of CD38, B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) and CD27 on CD21low B cells, which are additional features of terminal B-cell differentiation, was associated with HIV viraemia in genotypic and phenotypic analyses23. Thus, several B-cell manifestations of HIV infection in untreated individuals are reversed by effective ART.

B cells of HIV-viraemic individuals also express high levels of activation markers, including CD70, CD71, CD80 and CD86 (REFS 25–28). Several studies have shown that the expression of these activation markers is normalized by the ART-mediated decrease in HIV plasma viraemia23,25. HIV-induced B-cell activation in vivo has been shown to result in impaired function ex vivo, as measured either by the B-cell response to specific stimuli or by the ability of B cells to provide co-stimulatory signals to CD4+ T cells25,30,70. These findings indicate that HIV-induced hyperactivation of B cells inhibits their capacity to engage in effective cognate B-cell–T-cell interactions following encounter with antigen, a defect that could be exacerbated by Nef-induced inhibitory effects on the CD40 signalling pathway44.

One of the consequences of HIV-induced chronic immune-cell activation is increased cell turnover — that is, an increase in both proliferation and cell death. Several in vivo studies have shown increased turnover of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as of NK cells and B cells, during viraemic HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infections compared with the rate of cell turnover in the absence of infection; this increased turnover is reversed by ART24,71. In addition, expression of the cell cycle marker Ki-67 is increased in B cells from HIV-viraemic individuals compared with HIV-aviraemic and HIV-negative individuals23, and most of this increase in Ki-67 expression is by CD21low plasmablasts52 (FIG. 1). Furthermore, during non- pathogenic SIV infection in natural hosts, in which high viraemia persists in the absence of CD4+ T-cell depletion and progression to AIDS72, the turnover of B cells and other lymphocytes is similar to that of uninfected animals73. These differences between pathogenic and non-pathogenic SIV infection indicate that immune-cell activation, as reflected by increased cell turnover, is a key feature of HIV pathogenesis72.

In more recent comparisons between pathogenic and non-pathogenic SIV infections, a direct link was proposed between chronic immune-cell activation that is induced during pathogenic SIV infection and the expression of IFNα and ISGs34. By comparing several components of the innate immune response, this study showed that the absence of pathogenesis was associated with a low cell turnover and muted responses of pDCs, which are the main producers of IFNα. Low pDC responses have also been reported in another non-pathogenic SIV setting38. Several ISGs that are upregulated in B cells (and other lymphocyte populations) of HIV-viraemic individuals compared with HIV-aviraemic and HIV-negative individuals have been identified23, indicating that HIV viraemia is associated with the general induction of ISGs (reviewed in REF. 45). The data from pathogenic and non-pathogenic SIV infections suggest that during pathogenic HIV infection and ongoing viral replication, chronic immune-cell activation (of B cells and other immune cells) might be related to the ability of the virus to induce pDCs to secrete high and sustained levels of IFNα, although further studies are required to clarify this issue.

During chronic immune-cell activation induced by ongoing HIV replication, both cell proliferation and cell death are increased, with the net effect determining, at least in part, whether the total number of cells increases or decreases over time4. During the clinically asymptomatic phase of HIV infection, ongoing viral replication causes progressive CD4+ T-cell depletion, whereas the number of CD8+ T cells remains increased. In most HIV-infected individuals, the initiation of ART leads to a gradual increase in CD4+ T-cell counts and a decrease in CD8+ T-cell counts74. Although less is known about the effects of HIV infection on B-cell numbers, several studies have shown that B-cell numbers are decreased in HIV-infected individuals21,75–77. Furthermore, following ART, B-cell numbers increase and B-cell dynamics in response to infection and ART are more closely related to those of CD4+ rather than CD8+ T cells76,78. Although the redistribution of cells from tissues to peripheral blood might contribute to changes in B- and T-cell numbers before and after ART79, there are also many indications that an increased rate of B-cell death during ongoing viral replication contributes to a net loss of B cells23,80,81.

In this regard, several genes that are involved in the extrinsic apoptotic pathway are among the ISGs that are induced by HIV viraemia45,82. One such ISG encodes the death receptor CD95 (also known as FAS), the expression of which is increased by B cells from HIV-viraemic individuals83–85 and is largely confined to the expanded CD21low B-cell subpopulation23. The increased expression of CD95 has been associated with increased susceptibility of B cells to CD95-mediated apoptosis80, which in turn directly correlates with HIV viraemia23,81 (FIG. 2). Decreased B-cell survival in HIV-viraemic individuals has also been attributed to additional factors. These include the decreased responsiveness of B cells to the B-cell survival factor BAFF as a result of decreased expression of the BAFF receptor on CD21low B cells23 and the over-representation of immature transitional B cells, which are highly susceptible to intrinsic apoptosis as a result of decreased expression of pro-survival members of the B-cell lymphoma 2 family81. The increase in B-cell numbers with ART is accompanied by a decrease in the frequency and number of B cells that are prone to cell death, including activated mature CD21low B cells and immature transitional B cells76, thereby providing an explanation for why HIV viraemia is associated with a net loss of B cells.

In summary, the effects of ART on B cells are mainly attributed to the decrease in HIV viraemia, which leads to an overall decrease in B-cell turnover, hyperactivation and apoptosis. In addition, the increase in CD4+ T-cell counts following the reduction in HIV viraemia by ART is associated with a decrease in the frequency of immature transitional B cells.

B-cell defects that are not reversed by ART

Although most B-cell defects in HIV infection can be reversed by ART, one important exception is the loss of memory B cells and the decrease in memory B-cell function in chronically HIV-infected individuals (reviewed in REFS 86,87). However, the definition of what constitutes a memory B cell is an important consideration and a potential source of discordant interpretations of data, as HIV viraemia is associated with an increase in the number of short-lived B cells, including activated CD21low B cells and plasmablasts that express CD27 (FIG. 1), a marker that is often used to define memory B cells. Memory B cells are mostly regarded as long-lived, resting, antigen-experienced cells that are rapidly inducible after exposure to cognate antigen88. Based on this definition, studies have shown that although ART leads to decreased numbers of CD27+ activated B cells and plasmablasts29,76, the increase in the number of CD27+ resting memory B cells following treatment occurs slowly and remains incomplete76,85,89–91.

Numerous studies have shown that memory B-cell responses and serological memory against both T-cell-dependent and T-cell-independent antigens are decreased in HIV-infected individuals26,92–95. However, few studies have addressed the effect of decreasing HIV viraemia by ART on these responses. Initial findings from individuals who had received ART for a short time suggested that memory B-cell responses could be restored by ART96. By contrast, most of the more recent studies indicate that restoration of memory B-cell responses by ART is either absent or incomplete92–94. In many of the experiments, the B-cell responses that were measured were specific for T-cell-dependent antigens from influenza virus, measles virus and tetanus toxoid; in these cases, the persistence in the loss of CD4+ T-cell help could explain the lack of restoration of B-cell memory responses following the administration of ART. However, decreased memory B-cell responses against the polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine92,94, which is a T-cell-independent immunogen, indicate that HIV infection is also associated with intrinsic B-cell memory defects, and loss of responsiveness to pneumococcus was not reversed by ART. Recent findings indicate that this loss in memory function is associated with a decreased frequency of igm+ memory B cells92, a phenotype that is also seen in splenectomized individuals, who are also more susceptible to pneumococcal infection97. Given the proposed role of spleen-derived marginal zone B cells in responding to bacterial antigens98, these observations indicate that IgM+ memory B cells might be related to marginal zone B cells and might have a similar protective role against infection with encapsulated bacteria. The consequences of decreased B-cell responses to immunogens are particularly important in HIV-infected children, who are at a high risk of invasive pneumococcal infections99.

Effects of early initiation of ART on B cells

Few comprehensive studies have looked at B-cell numbers and function in HIV-infected individuals who initiate ART during the acute phase of infection. There are indications that B-cell functions, including memory B-cell responses, are impaired early after HIV infection63,83,94. Suggestions that the early initiation of ART might reverse immune defects remain anecdotal, although early initiation of ART does seem to reverse one defect of chronic HIV infection, the low frequency of IgM+ memory B cells83. Whether the restoration of normal numbers of IgM+ memory B cells translates into an improved responsiveness to T-cell-independent immunogens remains to be determined, as does the broader issue regarding the impact of early initiation of ART on the preservation of the immune system.

B-cell defects in other diseases

Advances in defining and characterizing the numerous B-cell subpopulations in humans are providing new insights into human immunology and new opportunities to understand the mechanisms of B-cell pathogenesis in various diseases that are characterized by immune dysfunction. During the delineation of B-cell dysfunctions in HIV, it became apparent that some of these abnormalities had been reported in other diseases in the absence of HIV infection. Common B-cell deficiencies are found across a broad range of infectious and non-infectious diseases of known and unknown origin. Although the complexities of each disease and the heterogeneity of any given condition can limit the number of clear associations, certain common pathways are worth considering (TABLE 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of HIV infection with other diseases that have B-cell defects

| Defect observed during HIV infection | Defect in other disease | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SlE | SS | SSc | CHC | malaria | ICl | CVID | WAS | CgD | |

| Activated CD21low B cells | Similar | ND* | ND | Similar (subset) | Similar | ND | Similar (subset) | Similar | Similar (subset) |

| Hypergammaglobulinaemia | Similar | Similar | Similar | Similar | Similar | ND | Opposite | ND | Conflicting reports |

| Increased B-cell apoptosis | Similar | Opposite | Similar | ND | Opposite | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Increased B-cell immaturity | Similar | ND | ND | Similar | ND | Similar | Similar (subset) | Similar (adults) | Similar‡ |

| Decreased number of memory B cells | Similar | Similar | Similar | Conflicting reports | ND | Similar | Similar (subset) | Similar | Similar |

| Presence of CD27− memory B cells | Similar | Similar | ND | ND | Similar | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Autoimmunity | Similar | Similar | Similar | Similar (subset) | Similar | Similar | Similar | Similar | Similar |

| B-cell malignancies | Similar | Similar | ND | Similar | Similar | ND | Similar | Similar | Similar |

| B-cell lymphopenia | Conflicting reports | Conflicting reports | Opposite | ND | ND | Similar (subset) | ND | Similar | ND |

| CD4+ T-cell lymphopenia | Similar | ND | ND | ND | ND | Similar | ND | Similar | ND |

ND in all instances indicates not determined or not notable.

S.M. and S.S. De Ravin, unpublished observations. CHC, chronic hepatitis C; CGD, chronic granulomatous disease; CVID, common variable immunodeficiency; ICL, idiopathic CD4+ T-cell lymphocytopenia; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SS, Sjögren’s syndrome; SSc, systemic sclerosis; WAS, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome.

Immature transitional B cells

Immature transitional B cells in the peripheral blood were first described as a transient subpopulation following bone marrow transplantation100 and were then shown to be an expanded population in the peripheral blood of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)101. The expansion of immature transitional B-cell populations has also been reported in several settings of immunodeficiency, including advancing HIV disease, common variable immunodeficiency and ICL49,50,92,102. Furthermore, immature transitional B cells can persist for several years at the expense of memory B cells in a subset of patients with SLE who were treated with the B-cell-depleting antibody rituximab103. Whether the clonal expansion and sustained high frequency of immature transitional B cells in various disease settings reflect a common driving factor in these diseases is not clear, although the presence of immature transitional B cells in these diseases is frequently associated with depleted memory B cells (TABLE 2). It is conceivable that immature transitional B cells arise from homeostatic pressures that are induced by lymphopenia and/or from conditions that increase the expression levels of early B-cell stimulatory factors such as BAFF and IL-7 (REFS 49,50,104). The consequences of increased numbers of immature transitional B cells in the peripheral blood are also not well understood, but further investigation is warranted given that this stage of development is characterized by high autoreactivity105, which is another manifestation of many diseases of B-cell dysregulation (TABLE 2).

Activated B cells

The presence of plasmablasts in the peripheral blood of HIV-viraemic individuals is probably a consequence of HIV-induced immune-cell activation. Increased numbers of plasmablasts in the peripheral blood have also been reported in several other diseases that induce B-cell hyperactivity, including other infectious diseases, autoimmune diseases and primary immunodeficiencies106–110 (TABLE 2). Furthermore, several of the same genes are upregulated in B cells from HIV-viraemic individuals and individuals suffering from SLE; these include genes that are associated with the terminal differentiation of B cells and type I IFNs23,108. Most recently, the identification of subpopulations of CD27− memory B cells in healthy human tonsils and in the peripheral blood of individuals with various conditions that are characterized by B-cell dysregulation (TABLE 2) indicates that certain microenvironments and inflammatory conditions can give rise to unique memory B-cell subpopulations that do not express the classic markers of B-cell memory52,57,61,111. A more comprehensive analysis of the properties of these cells could provide important insights into B-cell responses and B-cell dysregulation in various disease settings.

Concluding remarks

Several B-cell defects arise in HIV-infected individuals, particularly in individuals with chronically increased viral loads. The pathogenic nature of HIV-associated disease is characterized by chronic immune-cell activation, which involves increased cell turnover (increased proliferation, differentiation and cell death), the induction of high and sustained levels of IFNα, ISGs and other inflammatory factors such as TNF and LPS, and the premature exhaustion of cells involved in the adaptive immune response. The increased turnover of B cells induced by HIV leads to an increased frequency of short-lived plasmablasts that are probably responsible for the hypergammaglobulinaemia observed in HIV-viraemic individuals. Other B-cell-related manifestations of ongoing HIV replication include increased numbers of activated and exhausted B cells, increased levels in the circulation of immature transitional B cells associated with CD4+ T-cell lymphopenia and a decreased frequency of memory B cells that is not reversed by ART. In most HIV-infected individuals who start ART during the chronic stage of HIV infection, the irreversible loss of memory B cells is associated with poor responsiveness to T-cell-dependent and -independent antigens after vaccination or natural infection by secondary pathogens. Whether the loss of B-cell function can be reversed by early initiation of ART remains an open question.

Other open questions with potential implications for B cells include whether immune-modulating agents can reverse the defects that are induced by chronic HIV disease and whether therapies aimed at decreasing immune-cell activation can help to prevent the loss of immune function. In this regard, recent findings from a pathogenic SIV infection model indicate that in vivo treatment with antibodies that block the inhibitory receptor PD1 can improve B-cell responses112. Whether similar effects can be expected in humans is uncertain given the low level of expression of PD1 on B cells of HIV-infected individuals (S. M., unpublished observations). Further investigation is required to compare all aspects of B-cell dysregulation during HIV and SIV infection to more clearly define how the pathogenic mechanisms of B cells relate in these two settings. Nonetheless, such considerations have implications not only for preserving immune responses against secondary pathogens but also for preserving or boosting HIV-specific immune responses, including antibody responses. Finally, given the pivotal role of B cells in many human diseases and the number of similarities in B-cell defects observed across these diseases, the search for common pathways of pathogenesis should lead to a better understanding of the underlying causes of B-cell defects and to therapies that can reverse these defects.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. W. Chun, J. Chen and A. Waldner for suggestions on the manuscript and help with the figures. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Glossary

- Combination antiretroviral therapy

multi-drug therapy used to suppress viral replication and minimize viral resistance

- Memory B cell

A quiescent antigen-experienced B cell that can rapidly differentiate into a plasma cell on re-exposure to antigen

- Switched or unswitched antibody isotypes

Class switching of the immunoglobulin heavy chain from igm and igD to igG or igA or ige allows the diversification of the antibody repertoire, generating antibody isotypes with the same antigen specificity but with different effector functions

- Plasmablast

An antibody-secreting precursor of the non-dividing plasma cell that has the capacity to divide and migrate

- Hypergammaglobulinaemia

increased levels of immunoglobulin in blood serum

- Idiopathic CD4+ T-cell lymphocytopenia

A disorder of unknown cause that is characterized by decreased CD4+ T-cell counts in the absence of evidence for HiV-1 or HiV-2 infection or any known immunodeficiency or therapy associated with decreased levels of CD4+ T cells

- IgM+ memory B cell

An unswitched CD27+ memory B cell circulating in the peripheral blood that might be related to marginal zone B cells

- Marginal zone B cell

A mature B cell that is enriched anatomically in the marginal zone of the spleen, which is the interface between red pulp and white pulp

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

An autoimmune disease that is characterized by the potential for multiorgan involvement and production of antibodies that are specific for components of the cell nucleus

- Common variable immunodeficiency

A primary immunodeficiency disease with a heterogeneous cause and phenotype that is characterized by hypogammaglobulinaemia

Footnotes

DATABASES

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene BAFF | CD21 | CD27 | CD70 | CD71 | CD80 | CD86 | CD95 |FCRL4 | IFNα | IL-7 | PD1

FURTHER INFORMATION

Susan Moir and Anthony S. Fauci's homepage:http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/labs/aboutlabs/lir/immunopathogenesisSection/fauci.htm

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

References

- 1.Lane HC, et al. Abnormalities of B-cell activation and immunoregulation in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:453–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198308253090803. This study was the first to describe B-cell hyperactivity and dysfunction in individuals with AIDS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barre-Sinoussi F, et al. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popovic M, Sarngadharan MG, Read E, Gallo RC. Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science. 1984;224:497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.6200935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossman Z, Meier-Schellersheim M, Paul WE, Picker LJ. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nature Med. 2006;12:289–295. doi: 10.1038/nm1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sodora DL, Silvestri G. Immune activation and AIDS pathogenesis. AIDS. 2008;22:439–446. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2dbe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ammann AJ, et al. B-cell immunodeficiency in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. JAMA. 1984;251:1447–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pahwa SG, Quilop MT, Lange M, Pahwa RN, Grieco MH. Defective B-lymphocyte function in homosexual men in relation to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-6-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carbone A, et al. Lymph node immunohistology in intravenous drug abusers with persistent generalized lymphadenopathy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985;109:1007–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kekow J, Kern P, Schmitz H, Gross WL. Abnormal B-cell response to T-cell-independent polyclonal B-cell activators in homosexuals presenting persistent generalized lymph node enlargement and HTLV-III antibodies. Diagn Immunol. 1986;4:107–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnittman SM, Lane HC, Higgins SE, Folks T, Fauci AS. Direct polyclonal activation of human B lymphocytes by the acquired immune deficiency syndrome virus. Science. 1986;233:1084–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.3016902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kacani L, et al. Detachment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from germinal centers by blocking complement receptor type 2. J Virol. 2000;74:7997–8002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.7997-8002.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moir S, et al. B cells of HIV-1-infected patients bind virions through CD21-complement interactions and transmit infectious virus to activated T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:637–646. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malaspina A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 bound to B cells: relationship to virus replicating in CD4+ T cells and circulating in plasma. J Virol. 2002;76:8855–8863. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8855-8863.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thacker TC, et al. Follicular dendritic cells and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription in CD4+ T cells. J Virol. 2009;83:150–158. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01652-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen L, Siliciano RF. Viral reservoirs, residual viremia, and the potential of highly active antiretroviral therapy to eradicate HIV infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rappocciolo G, et al. DC-SIGN on B lymphocytes is required for transmission of HIV-1 to T lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e70. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He B, et al. HIV-1 envelope triggers polyclonal Ig class switch recombination through a CD40-independent mechanism involving BAFF and C-type lectin receptors. J Immunol. 2006;176:3931–3941. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berberian L, Goodglick L, Kipps TJ, Braun J. Immunoglobulin VH3 gene products: natural ligands for HIV gp120. Science. 1993;261:1588–1591. doi: 10.1126/science.7690497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moir S, et al. HIV-1 induces phenotypic and functional perturbations of B cells in chronically infected individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10362–10367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181347898. By identifying terminally differentiated CD21low B cells in HIV-viraemic individuals, the authors provide insight into the hypergammaglobulinaemia that is associated with HIV disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Notermans DW, et al. Potent antiretroviral therapy initiates normalization of hypergammaglobulinemia and a decline in HIV type 1-specific antibody responses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1003–1008. doi: 10.1089/088922201300343681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shearer WT, et al. Prospective 5-year study of peripheral blood CD4, CD8, and CD19/CD20 lymphocytes and serum Igs in children born to HIV-1 women. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:559–566. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirai A, Cosentino M, Leitman-Klinman SF, Klinman DM. Human immunodeficiency virus infection induces both polyclonal and virus-specific B cell activation. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:561–566. doi: 10.1172/JCI115621. This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of HIV-induced B-cell hyperactivity at the cellular level. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moir S, et al. Decreased survival of B cells of HIV-viremic patients mediated by altered expression of receptors of the TNF superfamily. J Exp Med. 2004;200:587–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs JA, et al. Identification of dynamically distinct subpopulations of T lymphocytes that are differentially affected by HIV. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1731–1741. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malaspina A, et al. Deleterious effect of HIV-1 plasma viremia on B cell costimulatory function. J Immunol. 2003;170:5965–5972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.5965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Milito A, et al. Mechanisms of hypergammaglobulinemia and impaired antigen-specific humoral immunity in HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2004;103:2180–2186. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Maza O, Crabb E, Mitsuyasu RT, Fahey JL, Giorgi JV. Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is associated with an in vivo increase in B lymphocyte activation and immaturity. J Immunol. 1987;138:3720–3724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Meijden M, et al. IL-6 receptor (CD126′IL-6R′) expression is increased on monocytes and B lymphocytes in HIV infection. Cell Immunol. 1998;190:156–166. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagase H, et al. Mechanism of hypergammaglobulinemia by HIV infection: circulating memory B-cell reduction with plasmacytosis. Clin Immunol. 2001;100:250–259. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conge AM, et al. Impairment of B-lymphocyte differentiation induced by dual triggering of the B-cell antigen receptor and CD40 in advanced HIV-1-disease. AIDS. 1998;12:1437–1449. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haynes BF, et al. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science. 2005;308:1906–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng VL. B-lymphocytes and autoantibody profiles in HIV disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 1996;14:367–384. doi: 10.1007/BF02771753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez-Maza O, Breen EC. B-cell activation and lymphoma in patients with HIV. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:528–532. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandl JN, et al. Divergent TLR7 and TLR9 signaling and type I interferon production distinguish pathogenic and nonpathogenic AIDS virus infections. Nature Med. 2008;14:1077–1087. doi: 10.1038/nm.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rieckmann P, Poli G, Fox CH, Kehrl JH, Fauci AS. Recombinant gp120 specifically enhances tumor necrosis factor-alpha production and Ig secretion in B lymphocytes from HIV-infected individuals but not from seronegative donors. J Immunol. 1991;147:2922–2927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weimer R, et al. HIV-induced IL-6/IL-10 dysregulation of CD4 cells is associated with defective B cell help and autoantibody formation against CD4 cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:20–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller F, Aukrust P, Nordoy I, Froland SS. Possible role of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and CD40 ligand expression in the pathogenesis of hypergammaglobulinemia in human immunodeficiency virus infection: modulation of IL-10 and Ig production after intravenous Ig infusion. Blood. 1998;92:3721–3729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diop OM, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell dynamics and α interferon production during Simian immunodeficiency virus infection with a nonpathogenic outcome. J Virol. 2008;82:5145–5152. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02433-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brenchley JM, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nature Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. References 37 and 39 indicate potential mediators of B-cell hyperactivity in HIV-infected individuals with chronic viraemia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Douek DC. HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nature Immunol. 2006;7:235–239. doi: 10.1038/ni1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner M, et al. IL-12p70-dependent Th1 induction by human B cells requires combined activation with CD40 ligand and CpG DNA. J Immunol. 2004;172:954–963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swingler S, et al. HIV-1 Nef intersects the macrophage CD40L signalling pathway to promote resting-cell infection. Nature. 2003;424:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nature01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swingler S, et al. Evidence for a pathogenic determinant in HIV-1 Nef involved in B cell dysfunction in HIV/AIDS. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiao X, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Nef suppresses CD40-dependent immunoglobulin class switching in bystander B cells. Nature Immunol. 2006;7:302–310. doi: 10.1038/ni1302. References 42–44 identify potential mechanisms of Nef-mediated B-cell hyperactivity and dysfunction in HIV-infected individuals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giri MS, Nebozhyn M, Showe L, Montaner LJ. Microarray data on gene modulation by HIV-1 in immune cells: 2000–2006. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1031–1043. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Napolitano LA, et al. Increased production of IL-7 accompanies HIV-1-mediated T-cell depletion: implications for T-cell homeostasis. Nature Med. 2001;7:73–79. doi: 10.1038/83381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fry TJ, et al. A potential role for interleukin-7 in T-cell homeostasis. Blood. 2001;97:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.LeBien TW, Tedder TF. B lymphocytes: how they develop and function. Blood. 2008;112:1570–1580. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-078071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malaspina A, et al. Appearance of immature/transitional B cells in HIV-infected individuals with advanced disease: correlation with increased IL-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2262–2267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511094103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malaspina A, et al. Idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia is associated with increases in immature/transitional B cells and serum levels of IL-7. Blood. 2007;109:2086–2088. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moir S, Fauci AS. Pathogenic mechanisms of B-lymphocyte dysfunction in HIV disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moir S, et al. Evidence for HIV-associated B cell exhaustion in a dysfunctional memory B cell compartment in HIV-infected viremic individuals. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1797–1805. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gallimore A, et al. Induction and exhaustion of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes visualized using soluble tetrameric major histocompatibility complex class I–peptide complexes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1383–1393. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Day CL, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trautmann L, et al. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nature Med. 2006;12:1198–1202. doi: 10.1038/nm1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaufmann DE, et al. Upregulation of CTLA-4 by HIV-specific CD4+ T cells correlates with disease progression and defines a reversible immune dysfunction. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:1246–1254. doi: 10.1038/ni1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ehrhardt GR, et al. Expression of the immunoregulatory molecule FcRH4 defines a distinctive tissue-based population of memory B cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:783–791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ehrhardt GR, et al. Discriminating gene expression profiles of memory B cell subpopulations. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1807–1817. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072682. References 52, 57 and 58 describe distinct memory B cells that might have immunoregulatory roles in health and disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wherry EJ, et al. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:670–684. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klein U, Dalla-Favera R. Germinal centres: role in B-cell physiology and malignancy. Nature Rev Immunol. 2008;8:22–33. doi: 10.1038/nri2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cagigi A, et al. Altered expression of the receptor-ligand pair CXCR5/CXCL13 in B-cells during chronic HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2008;112:4401–4410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shin H, Wherry EJ. CD8 T cell dysfunction during chronic viral infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morris L, et al. HIV-1 antigen-specific and -nonspecific B cell responses are sensitive to combination antiretroviral therapy. J Exp Med. 1998;188:233–245. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.233. This study was the first to describe changes in B-cell responses after effective ART. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nilssen DE, Oktedalen O, Brandtzaeg P. Intestinal B cell hyperactivity in AIDS is controlled by highly active antiretroviral therapy. Gut. 2004;53:487–493. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.027854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fournier AM, et al. Dynamics of spontaneous HIV-1 specific and non-specific B-cell responses in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2002;16:1755–1760. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jacobson MA, Khayam-Bashi H, Martin JN, Black D, Ng V. Effect of long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy in restoring HIV-induced abnormal B-lymphocyte function. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31:472–477. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Horvath A, et al. High level of anticholesterol antibodies (ACHA) in HIV patients. Normalization of serum ACHA concentration after introduction of HAART. Immunobiology. 2001;203:756–768. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(01)80004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malaspina A, et al. CpG oligonucleotides enhance proliferative and effector responses of B cells in HIV-infected individuals. J Immunol. 2008;181:1199–1206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jiang W, et al. Impaired naive and memory B-cell responsiveness to TLR9 stimulation in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:7837–7845. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00660-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moir S, et al. Perturbations in B cell responsiveness to CD4+ T cell help in HIV-infected individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6057–6062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730819100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Boer RJ, Mohri H, Ho DD, Perelson AS. Turnover rates of B cells, T cells, and NK cells in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected and uninfected rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 2003;170:2479–2487. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Silvestri G, Paiardini M, Pandrea I, Lederman MM, Sodora DL. Understanding the benign nature of SIV infection in natural hosts. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3148–3154. doi: 10.1172/JCI33034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaur A, et al. Dynamics of T- and B-lymphocyte turnover in a natural host of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2008;82:1084–1093. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02197-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ribeiro RM. Dynamics of CD4+ T cells in HIV-1 infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:287–294. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bekker V, et al. Epstein–Barr virus infects B and non-B lymphocytes in HIV-1-infected children and adolescents. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1323–1330. doi: 10.1086/508197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moir S, et al. Normalization of B cell counts and subpopulations following antiretroviral therapy in chronic HIV disease. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:572–579. doi: 10.1086/526789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meira DG, Lorand-Metze I, Toro AD, Silva MT, Vilela MM. Bone marrow features in children with HIV infection and peripheral blood cytopenias. J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51:114–119. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmh096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Le Guillou-Guillemette H, et al. Immune restoration under HAART in patients chronically infected with HIV-1: diversity of T, B, and NK immune responses. Viral Immunol. 2006;19:267–276. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lederman MM. Immune restoration and CD4+ T-cell function with antiretroviral therapies. AIDS. 2001;15:S11–S15. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gougeon ML, et al. Programmed cell death in peripheral lymphocytes from HIV-infected persons: increased susceptibility to apoptosis of CD4 and CD8 T cells correlates with lymphocyte activation and with disease progression. J Immunol. 1996;156:3509–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ho J, et al. Two overrepresented B cell populations in HIV-infected individuals undergo apoptosis by different mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19436–19441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609515103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herbeuval JP, Shearer GM. HIV-1 immunopathogenesis: how good interferon turns bad. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Titanji K, et al. Primary HIV-1 infection sets the stage for important B lymphocyte dysfunctions. AIDS. 2005;19:1947–1955. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191231.54170.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Titanji K, et al. Low frequency of plasma nerve-growth factor detection is associated with death of memory B lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;132:297–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chong Y, et al. Selective CD27+ (memory) B cell reduction and characteristic B cell alteration in drug-naive and HAART-treated HIV type 1-infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:219–226. doi: 10.1089/088922204773004941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Milito A. B lymphocyte dysfunctions in HIV infection. Curr HIV Res. 2004;2:11–21. doi: 10.2174/1570162043485068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cagigi A, Nilsson A, De Milito A, Chiodi F. B cell immunopathology during HIV-1 infection: lessons to learn for HIV-1 vaccine design. Vaccine. 2008;26:3016–3025. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tarlinton D. B-cell memory: are subsets necessary? Nature Rev Immunol. 2006;6:785–790. doi: 10.1038/nri1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.D’Orsogna LJ, Krueger RG, McKinnon EJ, French MA. Circulating memory B-cell subpopulations are affected differently by HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21:1747–1752. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32828642c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jacobsen MC, et al. Pediatric human immunodeficiency virus infection and circulating IgD+ memory B cells. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:481–485. doi: 10.1086/590215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.De Milito A, Morch C, Sonnerborg A, Chiodi F. Loss of memory (CD27) B lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2001;15:957–964. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105250-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hart M, et al. Loss of discrete memory B cell subsets is associated with impaired immunization responses in HIV-1 infection and may be a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease. J Immunol. 2007;178:8212–8220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Malaspina A, et al. Compromised B cell responses to influenza vaccination in HIV-infected individuals. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1442–1450. doi: 10.1086/429298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Titanji K, et al. Loss of memory B cells impairs maintenance of long-term serologic memory during HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2006;108:1580–1587. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-013383. This study shows the early and sustained impairment of memory B-cell responses in HIV-infected individuals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tejiokem MC, et al. HIV-infected children living in central Africa have low persistence of antibodies to vaccines used in the expanded program on immunization. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kroon FP, et al. Restored humoral immune response to influenza vaccination in HIV-infected adults treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1998;12:F217–F223. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199817000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kruetzmann S, et al. Human immunoglobulin M memory B cells controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are generated in the spleen. J Exp Med. 2003;197:939–945. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Martin F, Kearney JF. Marginal-zone B cells. Nature Rev Immunol. 2002;2:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nri799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bliss SJ, et al. The evidence for using conjugate vaccines to protect HIV-infected children against pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:67–80. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Meffre E, et al. Circulating human B cells that express surrogate light chains and edited receptors. Nature Immunol. 2000;1:207–213. doi: 10.1038/79739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sims GP, et al. Identification and characterization of circulating human transitional B cells. Blood. 2005;105:4390–4398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cuss AK, et al. Expansion of functionally immature transitional B cells is associated with human-immunodeficient states characterized by impaired humoral immunity. J Immunol. 2006;176:1506–1516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Anolik JH, et al. Delayed memory B cell recovery in peripheral blood and lymphoid tissue in systemic lupus erythematosus after B cell depletion therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3044–3056. doi: 10.1002/art.22810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stohl W. B lymphocyte stimulator protein levels in systemic lupus erythematosus and other diseases. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002;4:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s11926-002-0044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wardemann H, et al. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Charles ED, et al. Clonal expansion of immunoglobulin M+CD27+ B cells in HCV-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2008;111:1344–1356. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Potter KN, et al. Disturbances in peripheral blood B cell subpopulations in autoimmune patients. Lupus. 2002;11:872–877. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu309oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bennett L, et al. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. J Exp Med. 2003;197:711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Odendahl M, et al. Disturbed peripheral B lymphocyte homeostasis in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2000;165:5970–5979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wehr C, et al. The EUROclass trial: defining subgroups in common variable immunodeficiency. Blood. 2008;111:77–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-091744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wei C, et al. A new population of cells lacking expression of CD27 represents a notable component of the B cell memory compartment in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2007;178:6624–6633. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Velu V, et al. Enhancing SIV-specific immunity in vivo by PD-1 blockade. Nature. 2008 Dec 10; doi: 10.1038./nature07662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Miller CJ, et al. Antiviral antibodies are necessary for control of simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J Virol. 2007;81:5024–5035. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02444-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gaufin T, et al. Limited ability of humoral immune responses in control of viremia during infection with SIVsmmD215 strain. Blood. 2009 Jan 23; doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Richman DD, Wrin T, Little SJ, Petropoulos CJ. Rapid evolution of the neutralizing antibody response to HIV type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4144–4149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630530100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wei X, et al. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mestecky J, et al. Paucity of antigen-specific IgA responses in sera and external secretions of HIV-type 1-infected individuals. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:972–988. doi: 10.1089/aid.2004.20.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Scamurra RW, et al. Mucosal plasma cell repertoire during HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:4008–4016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shattock RJ, Haynes BF, Pulendran B, Flores J, Esparza J. Improving defences at the portal of HIV entry: mucosal and innate immunity. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e81. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lopes-Carvalho T, Kearney JF. Marginal zone B cell physiology and disease. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2005;8:91–123. doi: 10.1159/000082100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Karlsson Hedestam GB, et al. The challenges of eliciting neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1 and to influenza virus. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:143–155. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Forster R, et al. Abnormal expression of the B-cell homing chemokine receptor BLR1 during the progression of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Blood. 1997;90:520–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]