Abstract

Objective:

To report the magnitude of underreporting of road traffic injury (RTI) to the police from population-based and hospital-based data in the urban population of Hyderabad, India.

Methods:

In a cross-sectional population-based survey, 10,459 participants aged 5-49 years (94.3% participation) selected using a three-stage systematic cluster sampling recalled reporting of the non-fatal RTI to police in the last 12 months and fatal RTI in the last 3 years. In addition, 781 consecutive RTI cases that came to the emergency department of 5 hospitals provided information on RTI reporting to the police.

Results:

In the population-based study, of those who had non-fatal RTI and sought out-patient or in-patient services, 2.3% (95% 1.1% to 3.5%) and 17.2% (95% CI 3.5% to 30.9%) respectively, reported RTI to the police. Of the non-fatal consecutive RTI cases who came to the emergency department, 24.6% (95% CI 21.3% to 27.8%) reported RTI to the police. In the population-based study, 77.8% (95% CI 65.1% to 90.5%) of the fatal RTI were reported to the police, and among consecutive fatal RTI cases who came to the emergency department 98.1% (95% CI 95.5% to 100%) were reported to the police. Not necessary to report and hit-and-run case were cited as the major reasons for not reporting RTI to the police.

Conclusions:

As road safety policies are based on police data in India, these studies highlight serious limitations in estimating the true magnitude of RTI from these data, indicating the need for better methods for such estimation.

Keywords: India, road traffic injuries, underreporting

INTRODUCTION

Underreporting of deaths and injuries resulting from road traffic crashes (RTC) is a major global problem affecting many developing and developed countries around the world.[1-8] As road traffic injuries (RTI) are projected to be the third leading cause of disability-adjusted-life years lost globally by the year 2020,[9] a critical first step towards reducing the RTI burden is the availability of reliable, accurate and adequate data on RTC and the resulting fatalities and injuries.

Road safety in India is the responsibility of the Transport Ministry and the Police Department, with the role of the Health Ministry mostly being limited to provision of trauma care following road crashes.[10-11] The National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB) is the nodal agency responsible for the collection of data from police in each state/city, compilation, analysis and dissemination of injury-related information. According to NCRB, 105,725 people had died and 452,922 were injured in RTC in India in the year 2006.[12] There is a suggestion that these numbers are underreported, and some concerns have also been raised about the quality of these data.[13-16] Since policy makers utilize these data for identifying and prioritizing issues related to road safety intervention,[15] it is imperative to better understand the accuracy of these data.

We describe the magnitude and pattern of underreporting of RTI and the resulting fatalities to the police from two studies in the Indian city of Hyderabad. According to NCRB, 2,941 RTC had resulted in 532 people dead and 2,798 injured in Hyderabad in the year 2006.[12] Hyderabad has a population of 3.8 million excluding the surrounding areas that make up Hyderabad agglomeration,[17] and had 1.2 million registered motor-vehicles in 2001-2002 with the majority being motorized two-wheeled vehicles (77%).[18]

METHODS

These studies were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Administrative Staff College of India, Hyderabad, India.

Population-based study

The detailed methodology for population-based study is reported in the companion paper.[19] In brief, based on the census data for Hyderabad,[20] we selected the study population from 50 clusters using a three-stage random cluster sampling procedure and one cluster of 49 homeless persons to represent the 5-49 years age group in the population.[21] Trained interviewers obtained written informed consent from eligible people followed by confidential interview from October 2005 to December 2006. Of relevance to this paper, reporting of RTC to the police and type of treatment sought for the most recent RTI in the last 12 months were documented in addition to the vehicles involved, time of RTC and the number of people injured. Data on RTI related death of a household member in the last 3 years were documented by interviewing the head/lady of the household. RTI was defined as any injury resulting from RTC irrespective of the severity and outcome.[19]

Hospital-based study

Seven hundred and eighty one consecutive RTI cases reporting to the emergency department of two large public hospitals and three branches of a large private hospital in Hyderabad were recruited from November 2005 to June 2006. People of all ages with RTI (defined as in the population-based study) who either reported alive to the emergency department or were brought dead to these hospitals were included. Trained interviewers were posted round-the-clock in the emergency department and mortuary to capture all RTI cases. They documented the contact address of the RTI cases in detail to ensure that a follow-up was possible.

Interviews were conducted using a questionnaire designed for this study after obtaining written informed consent from the injured person or the care-taker or a responsible adult family member incase of death. Data were collected from the injured person where possible or from the care-taker or a responsible adult family member. Of relevance to this paper, detailed data on RTC that resulted in RTI were documented including reporting of RTC to the police. All recruited RTI cases (families in case of death) were followed up for a period of 6 months from the date of discharge/death. Reporting of RTC to the police was documented at follow-up for those who had not reported RTC to police during the first interview. The reasons for not reporting of RTC to police were also documented.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were entered in an MS Access database and SPSS was used for statistical analysis. The main outcome variable assessed was reporting of RTC resulting in RTI to the police which is done in India by registering of a First Information Report (FIR).[22] Data on the most recent non-fatal RTI in the last 12 months for participants aged 5-49 years and fatal RTI for all ages in the last 3 years from the population-based study, and non-fatal and fatal RTI cases from the hospital-based study for all ages were analysed. RTI resulting in death irrespective of the time gap between RTC and death was considered as fatal RTI. Follow-up could not be done for 24 (3.1%) non-fatal RTI cases in the hospital-based study. For these cases, the information provided in the first interview during the hospital admission was considered for analysis. Type of road user categories included pedestrian, cycle, motorised two-wheeled vehicle (MTV), motorised three-wheeled vehicle (commercial passenger vehicles: auto-rickshaw and seven-seater), car/jeep, and other vehicles (bus/tempo/truck/lorry).

Univariate and multivariate analyses were done separately for the two studies to understand the association of reporting the RTC resulting in RTI to the police with various characteristics to identify those that may play a significant role in determining this reporting. In the multiple logistic regression models, the effect of each category of a multi-categorical variable was assessed by keeping the first or the last category as reference, and all the variables were introduced simultaneously in the models. The reasons for not reporting RTC to police are reported for both studies. The 95% confidence intervals of estimates for the population-based study were calculated taking into account the design effect of the cluster sampling strategy,[23] and chi-square test for significance is reported where appropriate.

RESULTS

Participation

A total of 10,459 (94.3%) of the 11,097 eligible participants aged 5-49 years in the population-based sample were interviewed. 2,809 (26.9%) were 5-14 years of age, 1,372 (13.1%) were 15-19 years of age, 6,278 (60%) were 20-49 years of age and 5,376 (51.4%) were males.

Of the 781 prospective RTI cases in the hospital-based study, 610 (78.1%) were recruited from the two public hospitals and 171 (21.9%) from the three branches of the private hospital. Among these, 640 (81.9%) were males and 106 (13.6%) were fatal RTI cases of whom 40 (37.7%) were dead on arrival at the hospital.

Non-fatal RTI

In the population-based study, of the 1,032 (9.9%) most recent non-fatal RTI in the last 12 months, 336 (32.6%) were as a pedestrian and 367 (35.6%), 226 (21.9%), 35 (3.4%), 15 (1.5%) and 52 (5%) as a user of MTV, cycle, motorised three-wheeled vehicle, car/jeep, and other vehicle, respectively. Only 20 of the 1,032 most recent non-fatal RTI (1.9%, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.7) were reported to the police. Among 571 (55.4%) and 29 (2.8%) participants who had sought treatment as out-patient or as in-patient, 13 (2.3%, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.5) and 5 (17.2%, 95% CI 3.5 to 30.9) had reported RTC resulting in RTI to the police, respectively.

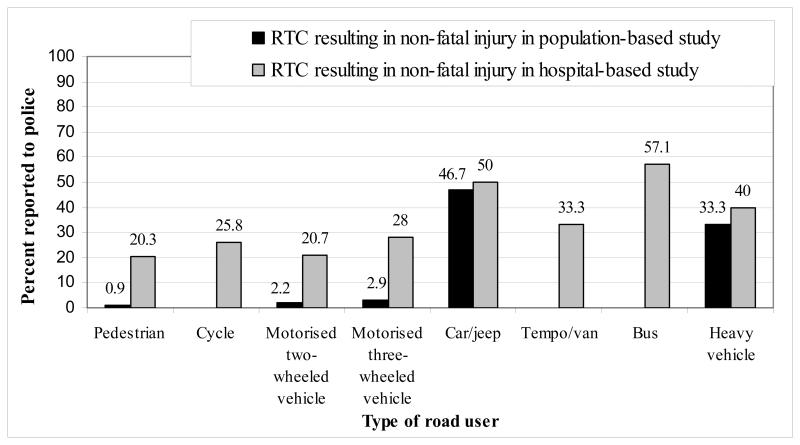

Among the 675 non-fatal RTI in the hospital-based study, 166 (24.6%, 95% CI 21.3 to 27.8) patients reported RTC resulting in RTI to the police. Significantly less reporting of RTI as a pedestrian (p<0.001), cyclist (p<0.001), MTV (p<0.001) or motorised three-wheeled vehicle (p<0.003) user was done to the police in the population-based study as compared with the hospital-based study (Figure 1). RTC involving car, jeep, and heavy vehicles as the other vehicle involved in RTC and those with >1 person injured had significantly higher odds of being reported to the police in both studies (Table 1). RTC involving the participants as occupant of car/jeep/tempo/van/heavy vehicle and those occurring between 2200 and 0600 hours reported in the population-based study were significantly more likely to be reported to the police but this was not significant in the hospital-based study. The RTI cases recruited from public hospitals were over twice more likely to report RTI to the police as compared with those recruited from private hospitals (Table 1). The results of multiple logistic regression analysis on considering only people who sought out-patient or in-patient services for RTI in the population-based study were similar.

Figure 1.

Percent of road traffic crashes (RTC) resulting in non-fatal injuries reported to police for the type of road user in the population-based and hospital-based studies in Hyderabad. Motorised two-wheeled vehicle includes moped, luna, scooter, scooterette and motorcycle; Motorised three-wheeled vehicle are commercial passenger vehicles and include auto-rickshaw and seven-seater.

Table 1.

Association of select variables with having reported road traffic crash (RTC) to the police that had resulted in non-fatal road traffic injury, using multiple logistic regression in the population-based and hospital-based studies in Hyderabad. Population-based study participants were aged 5-49 years and hospital-based study was of all ages. Data missing for 1 person in the population-based study.

| Variable | Population-based study | Hospital-based study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total RTC (1,031) |

RTC reported to police (% of total) |

Odds of reporting RTC to police (95% CI) |

Total (675) |

RTC reported to police (% of total) |

Odds of reporting RTC to police (95% CI) |

|

| Age group (years)* | ||||||

| 0-29 | 740 | 11 (1.5) | 1.00 | 333 | 95 (28.5) | 1.00 |

| >= 30 | 291 | 9 (3.1) | 1.72 (0.61-4.85) | 342 | 71 (20.8) | 0.73 (0.50-1.08) |

| Sex † | ||||||

| Male | 725 | 14 (1.9) | 1.91 (0.35-4.06) | 555 | 137 (24.7) | 0.78 (0.47-1.31) |

| Female | 306 | 6 (2.0) | 1.00 | 120 | 29 (24.2) | 1.00 |

| Type of road user ‡ | ||||||

| Motorised two/three wheeled vehicle |

402 | 9 (2.2) | 0.90 (0.20-4.05) | 416 | 90 (21.6) | 0.69 (0.43-1.12) |

| Car/jeep/tempo/van/heavy vehicles |

67 | 8 (11.9) | 11.27 (2.11-60.11) | 62 | 31 (50.0) | 1.26 (0.59-2.68) |

| Pedestrian/cycle | 562 | 3 (0.5) | 1.00 | 197 | 45 (22.8) | 1.00 |

|

Other vehicle involved in RTC§ |

||||||

| Car/jeep | 83 | 7 (8.4) | 10.75 (3.11-37.07) | 84 | 46 (54.8) | 4.28 (2.56-7.17) |

| Heavy vehicles | 15 | 2 (13.3) | 9.01 (1.22-53.67) | 99 | 32 (32.3) | 2.39 (1.44-3.98) |

| Others | 933 | 11 (1.2) | 1.00 | 492 | 88 (17.9) | 1.00 |

| Time of RTC (hours) # | ||||||

| 0600-1800 | 748 | 7 (0.9) | 1.00 | 357 | 98 (27.5) | 1.00 |

| 1801-2200 | 243 | 6 (2.5) | 2.40 (0.71-8.14) | 176 | 32 (18.2) | 0.63 (0.39-1.02) |

| 2201-0559 | 40 | 7 (17.5) | 11.90 (2.98-47.51) | 142 | 36 (25.4) | 0.79 (0.48-1.29) |

|

Number of people injured in RTC** |

||||||

| 1 | 787 | 5 (0.6) | 1.00 | 375 | 64 (17.1) | 1.00 |

| >1 | 244 | 15 (6.1) | 6.42 (1.99-20.73) | 299 | 101 (33.8) | 2.14 (1.40-3.29) |

| Type of hospital †† | ||||||

| Public | 164 | 23 (14.0) | 2.42 (1.42-4.14) | |||

| Private | 511 | 143 (28.0) | 1.00 | |||

5-29 years and 30-49 years for population-based sample; Chi-square test for significance: p=0.092 and 0.019 for population- and hospital-based sample, respectively.

Chi-square test for significance: p=0.975 and 0.905 for population- and hospital-based sample, respectively.

Motorised two-wheeled vehicles include moped, luna, scooter, scooterette and motorcycle; Motorised three-wheeled vehicle are commercial passenger vehicles and include auto-rickshaw and seven-seater; Heavy vehicles include truck, bus and lorry; Chi-square test for significance: p<0.001 for population- and hospital-based samples.

Heavy vehicles include truck, bus and lorry; Others include cycle, pedestrians, motorised two-wheeled ad three-wheeled vehicles; Chi-square test for significance: p<0.001 for population- and hospital-based samples.

Chi-square test for significance: p<0.001 and 0.063 for population- and hospital-based sample, respectively.

Chi-square test for significance: p<0.001 for population- and hospital-based samples; data missing on 1 person in hospital-based sample.

Not assessed for population-based sample; Chi-square test for significance: p<0.001 for hospital-based sample.

RTI resulting in expenditure of more than Indian Rupees 5,000 (US$ 124.4) were significantly more likely (p<0.001) to be reported to the police in both the population-based (18.6%) and hospital-based (46%) studies as compared with those that resulted in a lower expenditure (0.9% and 25.1% for population- and hospital-based studies, respectively). This variable was not included in the multiple logistic regression model, as the cost is a consequence of the RTI and we limited the model to the variables related directly to the RTC.

Fatal RTI

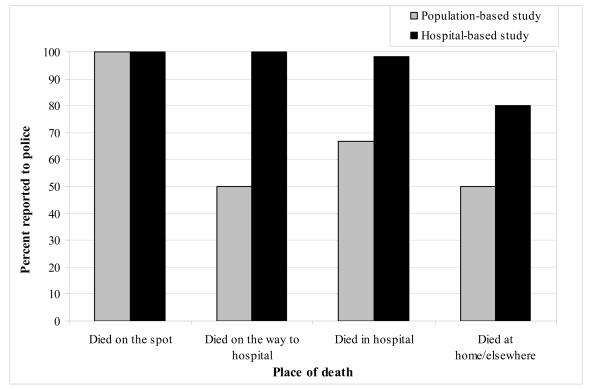

Eighteen deaths of all ages due to RTI in the last 3 years were reported in the population-based study. Among these, 8 (44.4%) had died on the spot, 2 (11.1%) on the way to hospital, 6 (33.3%) in a health facility and 2 (11.1%) at home. Fourteen (77.8%, 95% CI 65.1 to 90.5) fatal RTI were reported to the police. All RTC resulted in death on the spot were reported to the police (Figure 2). Of the 4 fatal RTI not reported to the police, 3 (75%) were males, 2 (50%) each were pedestrian and motorised three-wheeled vehicle user, and 3 (75%) were 50 years of age or more. In three of these cases, mistake of the deceased was thought to have resulted in RTC, 2 (66.7%) died within 6-12 hours of RTC and one on the way to hospital. The remaining one person had died >7 days post RTC.

Figure 2.

Percent of road traffic crashes (RTC) resulting in fatal road traffic injuries reported to police in the population-based and hospital-based studies in Hyderabad.

Of the 781 RTI cases in the hospital-based study, 106 (13.6%) were fatal. Among these fatal RTI, 17 (16%) had died on the spot, 22 (20.8%) on the way to hospital, 62 (58.5%) in the hospital, and 5 (4.7%) at home/elsewhere. All but 2 of these cases (98.1%; 95% CI 95.5 to 100) were reported to the police (Figure 2). The 2 cases that were not reported had died after >30 days since RTC, 1 each died at health facility and home/elsewhere (Figure 2).

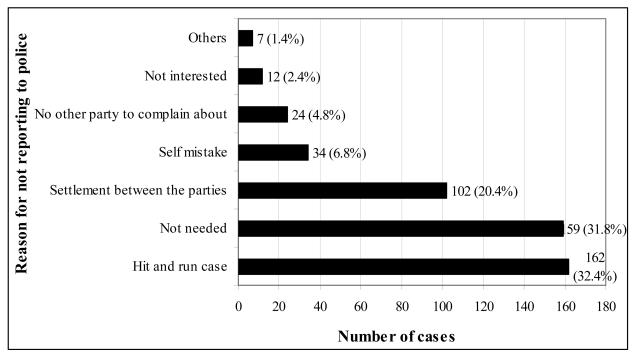

Reasons for not reporting to police

In the population-based study, among all the non-fatal RTI cases (1,032), those who had sought out-patient treatment (571) and in-patient treatment (29), 843 (81.4%), 440 (77.1%) and 7 (24.1%) mentioned that it was not necessary to report RTC to the police, respectively.

Of the 511 RTI cases in the hospital-based study who did not report RTC to police, 500 (97.8%) provided a reason for not reporting (Figure 3). Nearly similar proportions reported hit and run case (the other party ran away after RTC; 32.4%) and not needed (31.8%) followed by settlement between the parties (20.4%) as the reasons for not reporting to the police. Hit and run was cited as the reason for not reporting the 2 fatal RTI cases to the police.

Figure 3.

Reasons for not reporting road traffic crash resulting in road traffic injury to the police in the hospital-based study in Hyderabad.

DISCUSSION

Underreporting of deaths and injuries resulting from RTC is a major issue globally. We found gross underreporting and selective reporting of non-fatal RTI to the police in this urban Indian population. Only 17.2% and 2.3% of non-fatal RTI requiring treatment as in-patient and out-patient, respectively, in the population-based study were reported to the police, and 24.6% of the non-fatal RTI cases admitted in the hospital-based study were reported to the police. Even fatal RTI were under-reported, with 22% fatalities in the population-based study not reported to the police.

Police records are the main source of RTI related deaths and injuries information in India.[12] The police is required to file an FIR when RTC is reported to them so that the legal proceedings, if necessary, can be initiated. FIR can be filed by any person irrespective of whether he/she has first hand knowledge about the RTC.[22] Our data suggest that a large proportion of the people involved with RTC failed to report it to the police. Irrespective of the type of study, many people thought that it was not necessary to report RTC to the police and that they needed to have information on the other party to report to RTC to the police. Settlement between the two parties involved in RTC was also a common reason for not reporting to police. These data highlight the practical issues that need to be addressed in order to improve the reporting to police. Though mechanisms are in place to register FIR in India, it is not considered, in general, easy by people to interact with the police. It is widely known that the long drawn out administrative process including attendance in the court of law is a major deterrent for people to report RTC to police, therefore, not reporting it or settlement between those involved are the preferred options for the majority. We found selective reporting of RTC as RTC involving care/jeep and heavy vehicles, night time RTC and those with >1 person injured were reported in higher numbers in the population-based study which was more or less similar in the hospital-based study. In addition, RTC resulting in death and severe injuries were more likely to be reported to the police in the hospital-based study. The reporting to police also increased with increase in RTI related expenditure. These data highlight that people do not feel the need to report RTC to police unless the RTI is serious or compensation is needed, in which case also only less than one-fourth are reported to the police. RTI reporting to the police has been previously reported to be worse in less developed countries, with 70% of in-patient and 25% of out-patient RTI reported in the Netherlands [8] and 82% of RTI in Australia [6] as compared with 48% of hospital patients in India [24] and 4% of serious injuries in Pakistan.[7]

Police also gets information on RTC injuries and fatalities through hospitals. For the people injured or dead in RTC who report or are brought to a doctor, such cases are required by law to be documented in the Medico-legal case Register maintained by the doctor/hospital. The information from this is then expected to be given to the police on regular basis for further action. We reviewed this register and the process at one of the study hospitals. The register included information on the - name, age, sex, caste, occupation, address, identification marks, who brought the injured/dead to hospital, whether police has been notified, whether declaration to police is required, and nature of injury and treatment provided. No information was documented on the type of road user or RTC per se. The medical officer completing the register decided if the case should be reported to the police based on what he heard from the injured or any other person who provided the information. We also attempted to understand what happens in cases where information from the Medico-legal case Register was provided to the police. Interactions with a number of police officials at different levels revealed that there was an ambiguity about how this information was utilized or further documented by the police. Some suggested that the police attempts to contact the injured/family to seek details about RTC. Based on the level of information that they are able to gather from them and by enquiries at the RTC location, a decision is made whether or not a FIR is to be registered by police. On exploring this conditional FIR registration further, lack of human resources to deal with the RTC investigation and administrative work were elucidated as the main reasons for doing so. This lack of human resources has been documented previously.[13, 25] This suggests that the other reasons for underreporting are hospitals not presenting all cases to police, and police not recording all cases reported to them. These issues with reporting system are well acknowledged in India though the reporting system practice varies widely in India.[24]

In our studies, we documented RTI reporting to police by the respondent/care-taker. We did not attempt to link the information provided by the respondent/care-taker to the police records due to logistical issues in tracing records over the last 12 months in the background of poor and incomplete documentation by the police.[13] It is unlikely that we have overestimated the underreporting to police because in the event of someone else/hospital reporting RTC to the police, the respondent/care taker would have been contacted by police to seek further information to register FIR.

Underreporting of non-fatal RTI as MTV user, pedestrian and cyclists highlighted in the population-based study is a concern as these road users account for the majority of RTI in India.[16, 19] Since policy formulation and road safety interventions are based on the information available from the police records, it is clear that application of these data available with the police is seriously limited in projecting the true nature of RTI in India as it is unlikely to be focused on the road users that need attention. Pedestrian injuries have been underreported in linkage studies between hospital records/trauma registries with police crash data in Australia and UK,[6, 26-27] and cyclists injuries in the Netherlands.[8] Underreporting of RTI involving children has been documented from Japan, UK and the Netherlands.[4-5, 8] We did not find any significant association of age and sex with underreporting of RTI in this urban population.

On considering fatal RTI as died within 30 days since RTC, all fatal RTI in the hospital-based study were reported to the police, however, without limiting the definition, 2% fatal RTI were not reported. Underreporting of 5% deaths by police as compared with hospital records has been previously documented in Bangalore in India.[28] The population-based study suggested 22% underreporting of fatal RTI. All but one case was not reported because RTC was considered as the mistake of the deceased, thereby, highlighting the need for better information sharing with public about the importance of reporting fatal RTI to the police. This underreporting rate is lower than Pakistan wherein the death rate in Karachi was underestimated by 179% in the police records.[7]

The data from population- and hospital-based sample in the same population highlights the similarities and dissimilarities, and together provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex process of RTI reporting to the police. It also highlights the difference in the magnitude of underestimation when only hospital-based data are considered for comparison with the police data. The urgent need for improving the road safety information in India is recognized in the recent draft national road safety policy, which includes recommendations to improve reporting of crashes by the police and linkages between the police, vehicle and driver registration databases.[29] Our studies suggest that in addition improvements in the reporting system from the emergency departments and in-patient admission in hospitals for all fatal and non-fatal RTI to the police, increasing awareness in public about the need to report all fatal RTI to the police irrespective of the circumstances of RTC, are needed which will help improve the RTI estimates in India.

KEY MESSAGES.

What is already known?

Underreporting of road traffic injuries is a problem in India

Data mainly available from hospital records

What this study adds?

Only 17.2% and 2.3% of RTI requiring treatment as in-patient and out-patient, respectively were reported to the police in the population-based study

Only one-fourth of RTI coming to the emergency department in the hospitals were reported to the police

22% of the fatal RTI in the population-based study were not reported to the police

Not necessary to report RTI and no information on the other party were cited as major reasons for not reporting RTI to the police

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the contribution of GM Ahmed, Md Akbar, SP Ramgopal, N Balaji Rao, D Ram Babu and K Bhagawan Babu and YRK Satya Prasad in the implementation of this study.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the Wellcome Trust, UK (077002/Z/05/Z). R Dandona is supported in part by the National Health and Medical Research Council Capacity Building Grant in Injury Prevention and Trauma Care, Australia.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED

- CI

Confidence interval

- DE

Design effect

- MTV

Motorised two-wheeled vehicle

- RTC

Road traffic crash

- RTI

Road traffic injuries

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D, et al. World report on road traffic injury prevention. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameratunga S, Hijar M, Norton R. Road traffic injuries: confronting disparities to address a global-health problem. Lancet. 2006;367:1533–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68654-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odero W, Garner P, Zwi A. Road traffic injuries in developing countries: a comprehensive review of epidemiological studies. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:445–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakahara S, Wakai S. Underreporting of traffic injuries involving children in Japan. Inj Prev. 2001;7:242–4. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonard PA, Beattie TF, Gorman DR. Under representation of morbidity from pediatric bicycle accidents by official statistics--a need for data collection in the accident and emergency department. Inj Prev. 1999;5:303–4. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.4.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez DG, Rosman DL, Jelinek GA, et al. Complementing police road crash records with trauma registery data – an initial evaluation. Accid Anal & Prev. 2000;32:771–777. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razzak J, Luby SP. Estimating deaths and injuries due to road traffic accidents in Karachi, Pakistan, through capture-recapture method. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:86–870. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.5.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris S. The real number of road traffic accident casualties in the Netherlands: a year long survey. Accid Anal & Prev. 1990;22:371–378. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(90)90052-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray CJL, Lopez AD, Mathers CD, et al. Global Program on Evidence for Health Policy Discussion Paper No. 36. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. The Global Burden of Disease 2000 Project: aims, methods, and data sources (revised) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Transport Chapter in the 10th Five-year Plan. Planning Commission, Government of India; New Delhi: 2002. ( http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/10th/volume2/v2_ch8_3.pdf). Accessed 3 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Road Safety. Department of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India; New Delhi: ( http://morth.nic.in/index1.asp?linkid=77&langid=2). Accessed 9 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accidental deaths and suicides in India – 2006. National Crimes Record Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; New Delhi: 2005. ( http://ncrb.nic.in/ADSI2006/home.htm). Accessed 15 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dandona R, Mishra A. Deaths due to road traffic crashes in Hyderabad city in India: need for strengthening surveillance. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:74–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gururaj G. National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; New Delhi: Injuries in India: a national perspective. ( www.whoindia.org/LinkFiles/Commision_on_Macroeconomic_and_Health_Bg_P2__Injury_in_India.pdf). Accessed 3 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dandona R. Making road safety a public health concern with policy makers in India. Natl Med J India. 2006;19:126–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gururaj G. Road traffic deaths, injuries and disabilities in India: current scenario. Natl Med J India. 2008;21:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Registrar General of India . Population Totals: India, Census of India. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; New Delhi: 2001. ( http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/Census_Data_Online/Population/Total_Population.aspx). Accessed 20 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Category-wise vehicular strength in twin cities. Government of Andhra Pradesh; Hyderabad: ( http://www.aptransport.org/html/veh_strength.htm). Accessed 3 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dandona R, Kumar GA, Ahmed GM, et al. Incidence and burden of road traffic injuries in urban India. Inj Prev. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.019620. companion paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Registrar General of India . Andhra Pradesh, Census of India 2001, Primary Census Abstract. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; New Delhi: 2005. Data Product No. 00-63-2001-Cen-CD. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Director of Census Andhra Pradesh . Andhra Pradesh, Census of India 2001, Primary Census Abstract. Directorate of Census Operations, Government of Andhra Pradesh; Hyderabad: 2005. p. 671. [Google Scholar]

- 22.What is First Information Report? ( www.humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/police/fir.pdf). Accessed 10 April 2008.

- 23.Bennett S, Woods T, Liyanage WM, et al. A simplified general method of cluster-sample surveys of health in developing countries. World Health Stat Quart. 1991;44:98–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gururaj G. Road traffic injury prevention in India. National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro Sciences; Bangalore, India: 2006. (Publication No. 56). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dandona R, Kumar GA, Dandona L. Traffic law enforcement in Hyderabad, India. Int J Inj Control Saf Promot. 2005;12:167–76. doi: 10.1080/17457300500088840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teanby D. Underreporting of pedestrian road accidents. BMJ. 1992;304:422. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6824.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agran PF, Castillo DN, Winn DG. Limitations of data complied from police reports on pediatric pedestrian and bicycle motor vehicle events. Acc Anal & Prev. 1990;22:361–370. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(90)90051-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aeron-Thomas A, Jacobs GD, Sexton B, et al. The involvement and impact of road crashes on the poor: Bangladesh and India case studies. Transport Research Laboratory (TRL); Crowthrone: TRL Published Project Report. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Draft National Road Safety Policy as Recommended by Sundar Committee ( http://www.morth.nic.in/index2.asp?sublinkid=273&langid=2). Accessed 26 July 2008.