Abstract

Objectives

To develop and establish the validity and reliability of a conflict management scale specific to pharmacy practice and education.

Methods

A multistage inventory-item development process was undertaken involving 93 pharmacists and using a previously described explanatory model for conflict in pharmacy practice. A 19-item inventory was developed, field tested, and validated.

Results

The conflict management scale (CMS) demonstrated an acceptable degree of reliability and validity for use in educational or practice settings to promote self-reflection and self-awareness regarding individuals' conflict management styles.

Conclusions

The CMS provides a unique, pharmacy-specific method for individuals to determine and reflect upon their own conflict management styles. As part of an educational program to facilitate self-reflection and heighten self-awareness, the CMS may be a useful tool to promote discussions related to an important part of pharmacy practice.

Keywords: conflict management, pharmacy education, self-reflection, interprofessional

As pharmacists collaborate with physicians, nurses, patients, and others on a more frequent basis, the possibility of interpersonal conflicts developing increases.1-5 Consequently, understanding the nature of conflict in pharmacy practice and providing pharmacists with skills for managing interpersonal conflict are important from a quality of working life perspective,6,7 as well as from a human resources (recruitment/retention)8 perspective. Herzog's definition of conflict is widely accepted: interpersonal conflicts may exist whenever 2 or more individuals interact and disagree.9 Importantly, interpersonal conflict is frequently identified as an intellectual and/or moral disagreement, coupled with an emotional response from at least 1 of the parties involved.10

Much of the literature examining conflict in health care focused on interprofessional conflict (particularly between physicians and nurses). Gerardi noted that unaddressed conflict is a frequent cause of unhealthy nursing workplaces, and suggested educational strategies should be employed to empower nurses to understand and manage conflict rather than simply avoid it,11 a finding echoed by Fujiwara et al.12 Among nurses, there were important correlations between conflict management skills and staff morale, burnout, and job satisfaction. An individual's ability to cope with and manage conflict was essential to fostering successful workplace interprofessional and interpersonal interactions.13 There were similar findings in a study of surgeons.14

Skjorshammer described the polarizing nature of most physician-nurse conflicts and the role of professional cultures and stereotypes in exacerbating this polarization.15 Successful conflict management appears to be built on a foundation of self-reflection, self-awareness, and flexibility. In one study, nurses and physicians actually differed in their perception of when a difference of opinion actually became a conflict, and consequently, what appropriate action was required.16 In another study of health care practitioners, conflict avoidant behaviors were significant and a major managerial challenge to advancement of interprofessional collaboration.17

Individual conflict management styles exist and are relied upon by individuals in managing day-to-day conflict. The Thomas-Kilman Instrument has been widely used as a management training tool to assist individuals in identifying their own conflict style and learning new tactics for managing conflict that may be more successful in different situations.18 This instrument is built upon a model conceptualizing 5 different conflict management behaviors: avoidance, competition, compromise, accommodation, and collaboration. This model suggests that the collaborative style is superior to the other 4 and focuses on providing individuals who have one of the other styles with strategies to assist them in becoming more collaborative. Herzog used this instrument to examine conflict management styles of nurses, and provided specific behavioral guidelines for managing both patient-nurse and physician-nurse conflicts.9 In another study, the majority of nurses avoided conflict, with less than 10% actively adopting collaborative conflict resolution behaviors.19

Conceptualizing conflict management in terms of individual “styles” (or preferences for use of specific strategies) has provided researchers with unique opportunities to develop models and programs to facilitate practitioner development. A variety of strategies are utilized by community mental health workers, and individual preferences for use of specific strategies appears to be linked to individual conflict management styles.4,10

The role of self-reflection in conflict management has also gained prominence. Reflective practice was found to raise self-awareness, and self-awareness provides opportunities for conflict de-escalation.20 In examining conflicts between patients and physicians, lack of self-awareness on the part of the physician as to the impact of his/her words on the patient was a significant cause of conflict or the escalation of a disagreement into conflict.21 A conflict management checklist was developed for physicians to assist them in self-reflection and identification of behavioral patterns that may exacerbate conflict.22

The literature on interpersonal conflict in pharmacy practice is somewhat scant compared to that on other professions. Much of what has been reported focuses on workplace satisfaction or the impact of extrinsic motivating factors on employment choices.6,7 Few reports on pharmacy curricula have explicitly addressed the importance of teaching conflict management skills to pharmacy students. One study identified interpersonal conflict as one of the most significant problems that pharmacists face, one of the major reasons why pharmacists choose to leave the profession, and one of the major predictors of pharmacist dissatisfaction in the workplace.8 With expansion of interprofessional collaborative practice, interactions between pharmacists and other health professionals have increased and this has introduced new challenges into the day-to-day practice of pharmacy.23

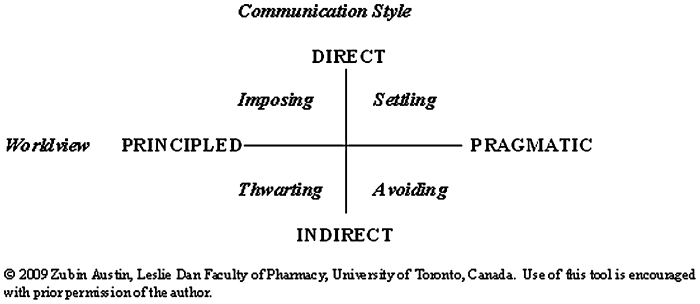

We have reported on the nature of conflict in community pharmacy practice, and identified diverse triggers for interpersonal conflict between pharmacists and others (including pharmacy technicians, physicians, and patients).24 Based on this work, an explanatory model for interpersonal conflict in community pharmacy practice was generated. This model proposed that conflict is based on 2 individual processes: worldview and communication style. Worldview exists upon a continuum ranging from highly pragmatic (flexible, open to compromise, “shades-of-gray” thinking) to highly principled (clear distinction between right and wrong, strong belief in one's own convictions, a tendency toward “black-and-white” thinking). Communication style exists upon a continuum ranging from direct (forceful, focused, with little attention to nuance and little regard for the response of others) to indirect (circuitous with high regard for nuance and considerable attention paid to the response of others). The intersection of these 2 processes gives rise to 4 independent conflict management styles or stances (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conflict Management Model for Pharmacists.

Conflict style inventories have been utilized since the 1960s, to prompt self-reflection and promote self-awareness related to conflict management. The Thomas-Kilmann instrument (TKI) is among the most widely utilized and accepted of these types of self-assessment instruments.18 The TKI has many advantages, including a rigorous development/validation process, ease of use, and significant support provided to users and test administrators. However, commercially available inventories such as the TKI are frequently costly to administer and score, and in many cases, educators simply do not have financial or other resources available to use them. Second, the design and structure of such inventories (in particular the TKI) tends to be prescriptive. For example, the TKI suggests that the “collaborative” style is superior to all other styles, instead of taking a more nuanced approach which recognizes that specific styles may have specific advantages in particular circumstances. Finally, commercial inventories were generally developed within a managerial rather than an educational or health care context. While there are significant similarities between corporations/organizations, educational settings, and health care, there are also important differences that may not be adequately emphasized by these commercial instruments.

In order to address some of these disadvantages and limitations (particularly those related to cost of using commercially available inventories), and to construct an inventory that is based upon a model of conflict specific to pharmacy practice, we undertook to develop, validate, and pilot test a conflict style inventory for pharmacists.

METHODS

A multi-stage development process was used, based on previously published work in developing a pharmacy-specific learning-styles inventory.25 This development process included the following stages: (1) identification of core constructs associated with conflict in pharmacy practice; (2) development and validation of an explanatory model for conflict in pharmacy practice; (3) development and validation of an instrument based upon this explanatory model; (4) field testing of the instrument and revisions; and (5) reliability and validity assessment of the instrument. Steps 1 and 2 have been reported previously and resulted in the conflict management model outlined in Figure 1.

Development and Validation of an Instrument

For this study, a group of 20 pharmacists were recruited to participate in development and validation of the instrument. These pharmacists (from a variety of settings, including community, hospital, and primary care/ambulatory practices) were recruited from continuing education events held for pharmacists, and provided informed consent (pursuant to an ethics protocol approved by the University of Toronto's research ethics board). Participants were all volunteers; no compensation was provided for participation in this study (although refreshments were provided at focus group meetings and individuals who required parking subsidies for these meetings were able to receive them).

Focus group meetings consisting of 4-7 pharmacists were arranged (total of 4 meetings). At each meetings, participants were informed of the purpose of the study (to develop and validate a conflict management inventory), and were presented with the explanatory model which had been previously developed and validated. At these focus group meetings, participants were asked to reflect upon and share their own experiences with interpersonal conflict in the workplace, and to develop descriptions of how pharmacists with each of the different conflict stances described in the model would behave in practice. Based on these descriptions, a series of statements were developed by the investigators to illustrate how a pharmacist with a specific conflict stance would behave in practice.

As a result of these focus group discussions, 37 statements were developed. All participants in the study were then sent a survey (via SurveyMonkey (Portland, OR, www.surveymonkey.com)). The purpose of the online survey was to confirm the readability and understandability of each of these statements. For each of the 37 statements, participants were asked to (1) rephrase (summarize, encapsulate, or re-state) the essence of the statement; (2) provide feedback on the clarity of the statement; (3) indicate how other pharmacists may interpret (or misinterpret) the statement; and (4) provide suggestions for rewording the statement.

Based on results from this survey, the original 37 statements were modified; some statements were deemed to be sufficiently unclear and therefore dropped, while other statements were seen to be repetitive and consequently unnecessary. Other statements were modified based on participants' feedback. The 22 statements that emerged from this process were deemed to be sufficiently readable and understandable to continue through the development process.

The 22 refined statements were then re-circulated (again via SurveyMonkey) to the participants. Based on feedback from the second round of the survey, 3 of the statements were dropped because the majority of participants felt that the statements were redundant and/or unclear. Thus, out of an original bank of 37 statements, 19 were identified as being sufficiently robust (clear, comprehensible, and relevant) to be included in the inventory.

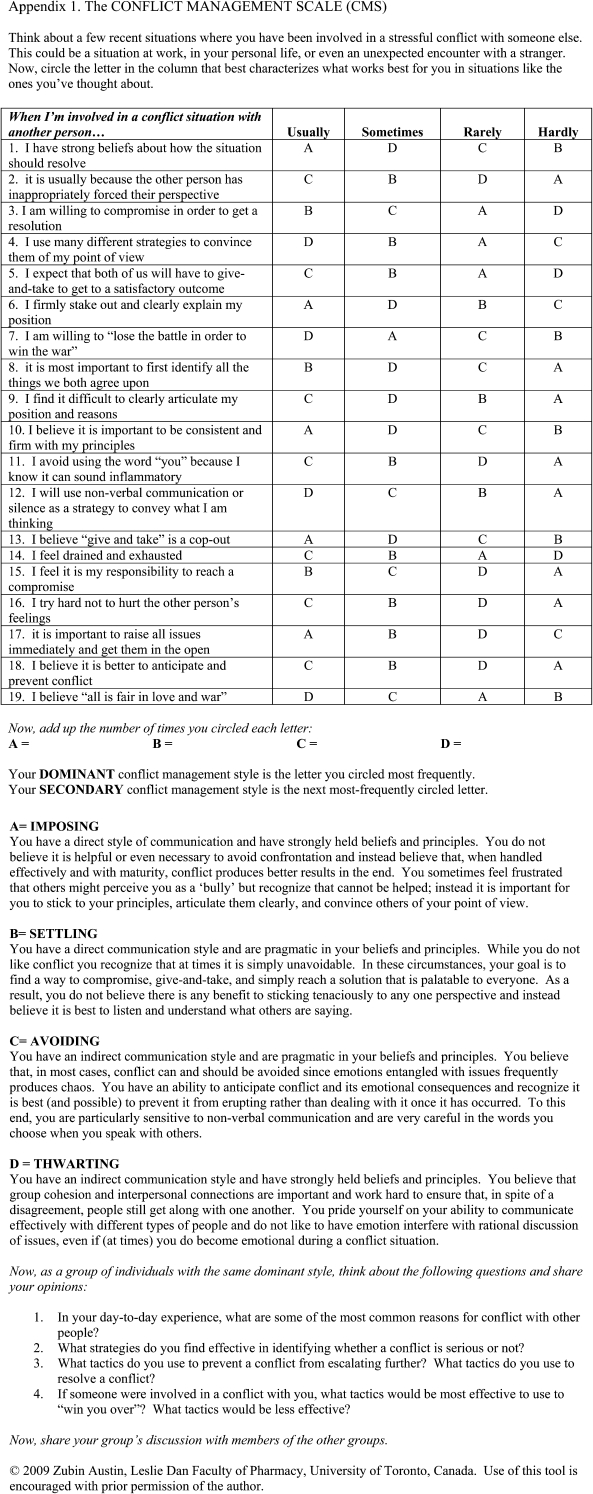

Scaling for this inventory was based on a 4-point scale. Since question items were developed that were behaviorally oriented (rather than requiring individuals to speculate on internal motivations), point-scaling was similarly behaviorally oriented: the terms “usually,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” and “hardly” were selected to avoid a middle-of-the-road response.

Field Testing of the Instrument and Revisions

Following assembly of the final 19-item inventory and accompanying descriptors (which were based on focus group findings), field testing of the instrument was undertaken with a purposeful sample of 22 senior-level pharmacy students, all of whom were volunteers. Once again, specific attention was paid to the readability and understandability of the instrument, as well as the participants' feedback regarding the ease of use and self-administration of the inventory. During field testing, groups of 4 to 6 students were gathered in focused groups and were presented the explanatory model and descriptors contained in the inventory. Students were then asked to self-assess their own dominant and secondary conflict management styles. Following completion of the inventory, students were asked once again to self-assess their dominant and secondary conflict management styles and indicate (on a 10-point scale) their degree of agreement with the results of the inventory.

Based on this field-testing, minor rewording and reformatting of the inventory were undertaken. No questions/items were dropped or significantly modified during this process. Participants required an average of 5.0 minutes (± 2.5 minutes) to complete the inventory. Participants were asked to rate the degree to which the inventory's categorization of their conflict management style correlated with their own self-perception; overall agreement with this categorization was 8.45/10.

Reliability and Validity Assessment of the Instrument

The psychometric properties of this inventory were evaluated in 3 different settings at 3 different times. Three sample frames of community pharmacists (n1 = 10, n2 = 21, and n3 = 20) were recruited from local continuing education events. Face validity and comprehensibility were measured through postinventory feedback provided by participants. Homogeneity of items was measured by calculating Pearson's correlation coefficients between each item, and a final score was calculated by removal of that specific item from the total summary score and ranking. Items with correlation coefficients < 0.2 were defined as outliers.

Reliability of the inventory was calculated using Cronbach's alpha (in the first instance for each of the 3 sample frames separately, then for the total n1 + n2 + n3 = 51). Determination of construct validity was undertaken through use of Spearman's correlation coefficients between the final score (ie, determination of dominant conflict style) and 2 postinventory satisfaction items. These items were based on work by Merritt and Marshall, and asked participants to (1) rank the accuracy of the statements regarding dominant and secondary conflict style; and (2) rank the degree to which the nondominant and nonsecondary styles were accurate reflections of their self-assessed conflict style.26 An ordinal scale (1-7) was used to rank these items.

RESULTS

Ninety-three pharmacists and pharmacy students participated in different stages of the development, piloting, and validation of this instrument. The resulting conflict management scale (CMS) is presented in Appendix 1. A high degree of reliability was demonstrated for the scale through Cronbach's alpha (between 0.811 and 0.865); mean alpha calculated across all samples was 0.845 (95% CI = 0.82 to 0.87). Spearman's correlations coefficients were calculated and indicated a moderate to high degree of construct validity. For item 1, correlations were moderately strong and positive (ranging from 0.64 to 0.68 for the 3 subgroups, and 0.66 for the combined sample).

There was a moderately strong and negative correlation for item 2 (ranging from -0.54 to -0.59 for the 3 subgroups, and -0.57 for the combined sample).

DISCUSSION

There are significant advantages to having a pharmacy-specific instrument such as this to identify conflict management styles. First, traditional instruments (such as the Thomas-Kilman Inventory) are generic, and validation studies were frequently used broad and heterogenous cohorts of individuals. Consequently, the constructs defined within such instruments, while generally applicable to all people, may lack the specificity of an instrument such as this. The methodical developmental process utilized in this study to develop and validate core constructs of relevance to pharmacists increases both the face utility of this tool within the pharmacy community and its applicability to professional practice. Second, the Thomas-Kilman Inventory, in particular, is constructed around the assumption that 1 conflict style (collaboration) is considered superior to others, without taking into account specific contexts or situations. This instrument utilizes a dominant/secondary conflict style approach without suggesting 1 style is superior to another. This approach appeared to be particularly important to participants in the validation process, who noted discomfort with the somewhat more prescriptive approach to conflict management dictated by the Thomas-Kilman Inventory. Since the purpose of this tool is not to make summary judgments regarding the adequacy of one's conflict management style, but instead to provide an opportunity for pharmacists to self-reflect upon their own experiences with conflict management (both positive and negative), it may be better suited for educational (rather than managerial) settings. In particular, the use of this tool by pharmacists and pharmacy students to reflect upon their own conflict management experiences for the purposes of self-improvement should be explored further. The value of such self-reflection in personal and professional development in health sciences education has been previously described by Plaza et al27; this instrument provides a concrete tool to facilitate and guide such reflective practice. Third, the approach used to develop, pilot, and validate this instrument may be broadly applicable to other situations where educational scholars wish to develop tools to measure certain constructs. Finally, it is the authors' intention that this scale be utilized freely and widely within the professional community. While traditional inventories may require users to pay fees for their use (or fees to have data analyzed and interpreted), this instrument was specifically designed to be self-administered and self-scored by those interested in learning more about their own conflict management style. Readers of the Journal are encouraged to use this instrument but to inform the authors' of its use so they may be aware of its application within the professional community.

Limitations

The developmental process described for this instrument follows traditional psychometric principles for reliability and validity assessment. The nature of such instruments and the data generated in this study suggests the conflict management scale may be a useful tool for self-reflection and for heightening self-awareness, but caution should be used in strictly interpreting its results. The tool was not intended to be used for stereotyping or diagnostic purposes, and time-series reliability testing was not undertaken as part of this study. The purpose of this instrument is more educational and consequently this additional psychometric analysis was deemed to be neither necessary nor appropriate.

Using the Conflict Management Scale

Since its development, the conflict management scale has been utilized in a variety of settings, including training programs for pharmacist and physician mentors/preceptors, as continuing professional education for pharmacists and physicians working in primary care settings, and with undergraduate pharmacy students prior to commencement of structured practical experience placements (ie, clerkships or internships). Thus far, the most significant role for the tool appears to be in its ability to prompt self-reflection, self-awareness, and discussion related to one's conflict management style. In some workshop settings, participants have been encouraged to apply their knowledge and understanding of conflict management styles, and their own self-awareness related to their personal style, in the context of role-playing exercises involving simulated patients and/or simulated health professionals. Further work in validation and assessment of the properties of this instrument within such educational settings is being undertaken. Educators who use this instrument are encouraged to disseminate their results and report on modifications or innovations they have incorporated.

CONCLUSIONS

As professional practice evolves, the extent of conflict will continue to grow. Conflict management is a core skill for health care providers, including pharmacists. The development of this conflict-management tool addressed a need for a reliable, valid, and cost-effective method for promoting self-reflection and self-awareness related to conflict management in pharmacy practice. Free use of this tool within the pharmacy education and practice community is encouraged, provided appropriate acknowledgement of the source and authors is made.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dower C, Christian S, O'Neill E. San Francisco: Centre for the Health Professions, University of California at San Francisco; 2007. Promising scope of practice models for the health professions; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beales J, Austin Z. The pursuit of legitimacy and professionalism: the evolution of pharmacy in Ontario (Canada) Pharm Historian. 2006;36(2):222–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Health Canada, Health Human Resources Strategy. Pan-Canadian Health Human Resources Planning. Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/hhr-rhs/strateg/plan/index-eng.php. Accessed October 19 2009.

- 4.O'Mara K. Communication and conflict resolution in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clinics North America. 1999;17:451–9. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worley-Louis MM, Schomer JC, Finnegan JR. Construct identification and measure development for investigating pharmacist-patient relationships. Pat Educ Counseling. 2003;51:229–38. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mott DA. Pharmacist job turnover, length of service, and reasons for leaving. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2000;57:975–84. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.10.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maio V, Goldfarb NI, Hartmann CW. Pharmacists' job satisfaction, variation by practice setting. Pharm Ther. 2004;29(3):184–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canadian Pharmacists' Association – Management Committee (2008). Moving Forward: Human Resources for the Future. Final Report. Ottawa (ON). Canadian Pharmacists' Association. Available at: http://www.pharmacygateway.ca/microsite/expandyourscope/pdfs/moving-forward.pdf Accessed: October 19 2009.

- 9.Herzog AC. Conflict resolution in a nutshell: tips for everyday nursing. Spinal Cord Injury Nurs. 2000;17:162–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagan M. Interpersonal conflict among staff of community mental health centres. Admin Pol Mental Health, Mental Health Serv Res. 1985;12(3):192–204. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerardi D. Using mediation techniques to manage conflict and create healthy work environments. American Assoc Crit Care Nurses Clini Issues. 2004;15:182–195. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujiwara K, Tsukishima E, Tsutsumi A, Kawakami N, Kishi R. Interpersonal conflict, social support, and burnout among home care workers in Japan. J Occup Health. 2003;45(5):313–20. doi: 10.1539/joh.45.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montoro-Rodriguez J, Small J. The role of conflict resolution styles on nursing staff morale, burnout, and job satisfaction in long-term care. J Aging Health. 2006;18(3):385–406. doi: 10.1177/0898264306286196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee L, Berger D, Awad S, Bradt M, Martinez G, Brunicardi F. Conflict resolution: practical principles for surgeons. World J Surg. 2008;Sept 12:187–96. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9702-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skjorshammer M. Understanding conflicts between health professionals: a narrative approach. Qual Health Res. 2002;7:915–31. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skjorshammer M. Cooperation and conflict in a hospital: interprofessional differences in perception and management of conflicts. J Interprofessional Care. 2001;15(1):7–18. doi: 10.1080/13561820020022837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skjorshammer M. Anger behaviour among professionals in a Norwegian hospital: antecedents and consequences for interprofessional collaboration. J Interprofessional Care. 2003;17(4):377–88. doi: 10.1080/13561820310001608203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahaim MA, Mager NR. Confirmatory factor analysis of the styles of handling interpersonal conflict: first-order factor model and its invariance across groups. J Appl Psych. 1995;80(1):122–32. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sportsman S, Hamilton P. Conflict management styles in the health professions. J Prof Nursing. 2002;23(3):157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross A, King N, Firth J. Relationships and collaborations: interpersonal relationships and collaborative working: encouraging reflective practice. Am Nursing Assoc Periodicals. 2005;10:95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharf BF. Physician-patient communication as interpersonal rhetoric: a narrative approach. Health Commun. 1990;2(4):217–31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siders CT, Aschenbrener CA. Conflict management: conflict management checklist – a diagnostic tool for assessing conflict in organizations. Phys Exec. 1999;25(5):51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Worley MM, Schommer JC. Pharmacists' therapeutic relationships with older adults: the impact of participative behaviour and patient centredness on relationship quality and commitment. J Soc Admin Pharm. 2002;19:180–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin Z, Gregory PAM, Martin JC. Pharmacists' management of conflict in community practice. Res Soc Admin Pharm. Accepted for publication: May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin Z. Development and validation of the pharmacists' inventory of learning styles (PILS) Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(2) Article 37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merritt SL, Marshall JC. Reliability and construct validity of alternate forms of the CLS inventory. Adv Nurs Sci. 1984;7:78–85. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198410000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plaza CM, Draugalis JR, Slack MK, Skrepnek GH, Sauer KA. Use of reflective portfolios in health sciences education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2) doi: 10.5688/aj710234. Article 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]