Abstract

Objectives

To develop and implement a new course on public health into the bachelor of pharmacy (BPharm) curriculum in Malaysia.

Design

A required 2-credit-hour course was designed to provide an overview of public health pharmacy roles and the behavioral aspects of human healthcare issues. Graded activities included nursing home visits, in-class quizzes, mini-projects, and poster sessions, and a comprehensive final examination.

Assessment

The majority of the students performed well on the class activities and 93 (71.5%) of the 130 students enrolled received a grade of B or higher. A Web-based survey was administered at the end of the semester and 90% of students indicated that they had benefited from the course and were glad that it was offered. The majority of students agreed that the course made an impact in preparing them for their future role as pharmacists and expanded their understanding of the public health roles of a pharmacist.

Conclusions

A public health pharmacy course was successfully designed and implemented in the BPharm curriculum. This study highlighted the feasibilities of introducing courses that are of global relevance into a Malaysian pharmacy curriculum. The findings from the students' evaluation suggest the needs to incorporate a similar course in all pharmacy schools in the country and will be used as a guide to improve the contents and methods of delivery of the course at our school.

Keywords: public health, curriculum, Malaysia

INTRODUCTION

Throughout modern history, pharmacists have played a role in promoting, maintaining, and improving the health of the communities they serve. The role of the pharmacist has expanded from the traditional role of dispensing medications to that of an integral part of the health care team, with an expertise in patient drug therapy management.1-3 In response to the growing demand for pharmacists who are knowledgeable in both pharmacy and population-based healthcare, there is a pressing need for future pharmacists to understand the broader concept of public health, which focuses on improving health at a population level.2, 4-6 Public health was defined by Sir Donald Acheson in 1988, as “the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting, protecting and improving health through organized efforts of society.”7 A population approach does not detract from individual needs, but adds another dimension, because individuals benefit from the information derived from the populations to which they belong.8 Pharmacy-related health improvement services are already well recognized and should be continuously expanded in the context of health promotion.9-12

A review of the published evidence from 1990-2001 relating to pharmacists' attitudes and perceptions towards their role in improving public health showed that they were more comfortable with activities related to medicines and needed additional training to extend their range of health-care activities.13 The findings of this review have important implications for educators and trainers of pharmacists at undergraduate and postgraduate levels.13 In most developed nations of the world, many pharmacy schools have integrated public health pharmacy courses as one of the core subjects to be taught in their undergraduate curriculums.14,15 In Malaysia, improving public health is firmly on the national healthcare agenda and the government's health policy offers an unparalleled opportunity for pharmacists to be recognized as part of the public health workforce. In order to practice effectively in the area of public health, there is a corresponding need for Malaysian pharmacy students to be adequately trained and exposed to the contemporary issues and challenges of public health delivery.

An experience in designing and implementing a public health pharmacy course for an undergraduate curriculum from the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) is described in this paper. The article also describes the pharmacy students' perceptions of the new course. The course was intended to introduce public health components of care at an early stage of the pharmacy curriculum and provide students with the knowledge of social and behavioral aspects of health care, such as the socio-epidemiological patterns of chronic diseases in the country and insight into healthcare-seeking behaviors among multicultural ethnic groups in Malaysia. This in return would further enhance the students' ability to understand the magnitude of public health issues which might affect the delivery of effective health care services in Malaysia. The key learning outcome of the course was for pharmacy students to be able to integrate and apply the concepts of public health gained from the didactic components into real-life situations in the community.

DESIGN

Description of the Public Health Pharmacy Course

The Public Health Pharmacy course was introduced during the academic year 2006-2007. The course was offered during the first semester for first-year students enrolled in the bachelor of pharmacy (BPharm) degree program. The course is a 2-credit-hour required (core) course, with a total of 24 contact hours: 14 contact hours (14 lectures × 1 hour) for didactic lectures; 4 contact hours (4 visits × 3 hours) for nursing home attachment; 1 contact hour (1 session × 3 hours) for training on cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and first aid; and 5 contact hours (5 sessions × 1 hour) for consultation with respective lecturers regarding public health pharmacy research mini-projects. Emphasis was placed on the role of pharmacists in health promotion and disease prevention by giving examples of pharmacists' involvement in public health issues such as smoking cessation, weight management, and cardiovascular health. Students also were expected to understand the socio-behavioral aspects of health and wellness, as well as the social responsibilities of pharmacist to the healthcare system and society. This was assessed through students' group project presentations and short quizzes. Faculty members in the Department of Social and Administrative Pharmacy taught and precepted the course.

Course Delivery Methods

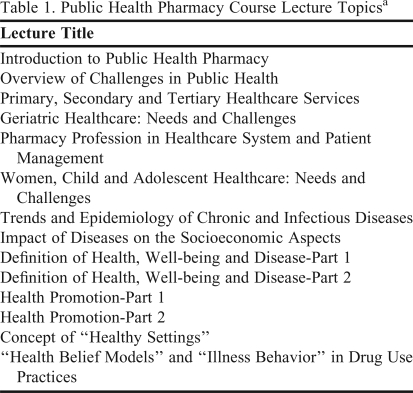

The main instructional strategies for the course include didactic lectures and group visit to nursing home in order to expose students to nursing home care in general. Beside this, during the visit, the students were expected to learn skills on medication review and counseling. A 3-hour training session on administering CPR and first aid were also incorporated into the course. The didactic lecture topics are provided in Table 1. A wide range of health promotion and disease prevention activities such as smoking cessation intervention, cholesterol and blood pressure screening, and diabetes education are widely available in community pharmacy settings in Malaysia, which entails an unprecedented opportunity for students' attachments and learning. In this course, however, nursing home care was chosen in lieu of community pharmacy settings to avoid duplication of experience gained in other pharmacy practice-based courses.

Table 1.

Public Health Pharmacy Course Lecture Topicsa

All lectures were approximately 1 hour in length.

Students' performance in the course was evaluated based on short quizzes and weekly nursing home visit reports (30% of course grade), group mini-project and poster presentation (20%), and CPR and first aid competency (10%). Students' performance on a comprehensive final semester examination covering the didactic components of the course accounted for the remaining 40% of their grade.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

One hundred thirty students completed the Public Health Pharmacy course in 2006-2007. The overall performance of the students was satisfactory with nearly half (49.6%) attaining a minimum grade of A- for the quizzes, mini-project, and CPR competency. Analysis of students' performance on final semester examination, which accounted for the remaining 40% of the final grade revealed that 15% of the students obtained a grade of B and above.

Students' Evaluation of the Course

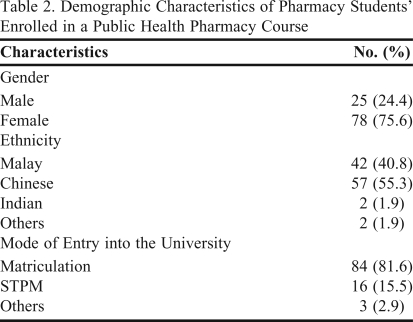

A 17-item Web-based questionnaire was administered to assess students' perceptions of the course. The link to this Web-based questionnaire was sent to the e-mail addresses of all first-year pharmacy students who took the course. Thirteen of the items used a 4-point Likert-type scale for responses (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree). One hundred three (79%) students completed the online survey instrument. The mean age of participants was 19.5 ± 3.1 years and approximately 76% were female (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Pharmacy Students' Enrolled in a Public Health Pharmacy Course

S

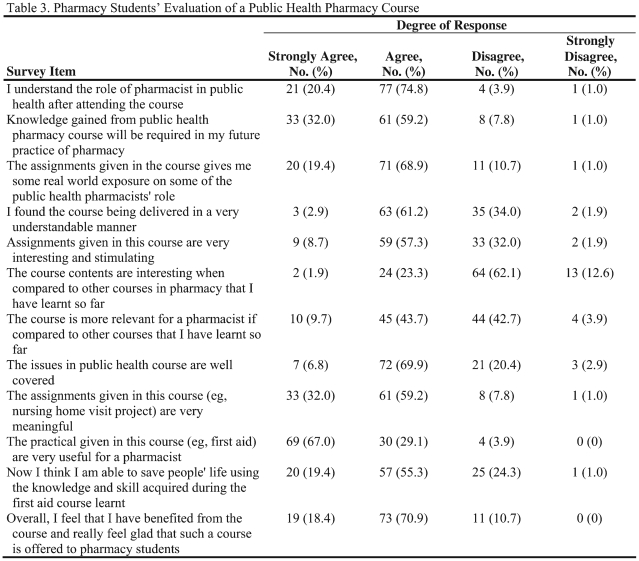

The students' overall perception of the new course was positive. The majority (over 80%) believed that: they understood the role of pharmacist in public health after attending the course (95.2%); the knowledge gained from the course would be required in their future practice of pharmacy (91.2%); and the assignments given in the course gave them some real-world exposure to the roles of pharmacists in public health (88.3%). However, more than half of the students disagreed that the content of the course was interesting compared to other courses in pharmacy, and a substantial proportion (47%) disagreed that the public health course was more relevant than other courses taught in the curriculum in the context of pharmacy practice. More than three-fourths of the students agreed that public health issues were well covered in the course and that they would be able to save lives using the knowledge and skills acquired from the first aid topics. Over 90% found that the assignments given, such as nursing home visit projects, and the skills acquired in the course, such as first aid techniques, were meaningful and useful for a pharmacist. Overall, the majority of the students (89%) felt they had benefited from the public health pharmacy course and were glad that such a course was offered to them. More information on the students' perception of the course is presented in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

An emphasis on health promotion and disease prevention within the health care delivery system is mandated by many health authorities and professional bodies around the world. For example, one of the key objectives stated in the United States' Healthy People 2010 agenda is to increase the proportion of schools of medicine, schools of nursing, and health professional training schools whose basic curriculum for healthcare providers includes the core competencies in health promotion and disease prevention.16 Similarly in Malaysia, health promotion and disease prevention strategies have been advocated by the Ministry of Health.17 Furthermore, calls have been made to collectively move health professions from the current treatment-oriented focus to a prevention-oriented focus.18 Within this context, there is a need for future health professionals to be well equipped with knowledge and skills in public health, and the pharmacy profession is not an exception. In order to address this challenge, the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the USM, which is the premier pharmacy school in the country, managed to introduce a required course on public health for its undergraduate students.

Furthermore, with introduction of any new course, there are almost always individual and contextual barriers to implementation, adoption, and acceptability.19,20 In order to assess the perceptions of the pharmacy students toward the introduction of this new public health pharmacy course in the BPharm curriculum, the Web-based survey was conducted. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the perceptions of students on a public health pharmacy course from the perspective of a developing country. The vast majority of participants believed that the public health pharmacy course helped to increase their understanding of the pharmacist's role in public health and would be useful in their future pharmacy practice. Nevertheless, there is always room for improvement in the offering and delivery of a new course. This is reflected in students' negative perceptions towards the course's usefulness and its attractiveness compared to other courses. The timing of the course introduction in relation to the BPharm curriculum may have affected students' perception of the course, since it was offered during the first semester of the first year of the degree program, and consequently, is the first pharmacy practice course taught. Most of the courses offered during this time are fundamental basic science courses such as physiology, medicinal chemistry, and pharmaceutical microbiology, so the students may have found their first experience in a community-based pharmacy course to be different and confusing. A better option may be to offer the course in the second or third year of the BPharm program when most of the other pharmacy practice courses are offered.

The results of this survey reaffirm the importance of experiential components of learning in a public health course as tools to improve knowledge and skills. The use of stimulating tools such as exposure to real-life scenarios has been advocated to aid learning and attainment of higher cognitive levels among students.21 For instance, the socio-behavioral aspects of nursing home inhabitants are unique and increased pharmacist involvement will have an impact on their well-being as most of these inhabitants do not have contact with their families and feel isolated and depressed. Therefore, it is vital for students to have insight into this issue and to learn specific counseling skills. The challenge in designing a good practical assignment is providing enough depth while making it attractive for the students. Although most of the students found that the public health course was meaningful, a substantial proportion found it less interesting than other courses. However, the course is worth only 2 credits and the majority of the curriculum is still focused on basic and clinical sciences, with little focus on social and public health-related courses.

SUMMARY

There is a need to introduce a well-structured public health course in the undergraduate pharmacy curriculum. This is in line with the ever-expanding role of pharmacists, especially in the area of public health worldwide. A Web-based survey revealed that the majority of pharmacy students who took the public health pharmacy course recognized the importance of the course to their future practice. Based on student evaluations of the course, further enhancement of the content is needed to make it more relevant to pharmacy practice in Malaysia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson S. The state of the world's pharmacy: a portrait of the pharmacy profession. J Interprofessional Care. 2002;16(4):391–404. doi: 10.1080/1356182021000008337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rijk AD, Raak AV, Made JVD. A new theoretical model for cooperation in public health settings: the RDIC model. Quality Health Res. 2007;17(8):1103–16. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blenkinsopp A, Anderson C, Armstrong M. Community pharmacy's contribution to improving the public's health: the case of weight management. Int J Pharm Pract. 2008;16:123–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson JKS, Michelle, Spinks JM, Snell B, Duncan GJ. Public health - recognising the role of Australian pharmacists. J Pharm Pract Res. 2004;34(4):290–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jesson J, Bissell P. Public health and pharmacy: a critical review. Crit Pub Health. 2006;16(2):159–69. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones C, Armstrong M, King MJ, Pruce D. How pharmacy can help public health. Pharm J. 2004;272:672–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Acheson D. Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the future development of the public health functions. London: HMSO; 1988:289. http://www.archive.officialdocuments.co.uk/document/doh/ih/ih.htm.

- 8.Anderson C. Pharmacist advocates of public health. Pharm J. 2006;277 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farhan F. Give students a better deal for health. Pharm J. 2004;272:345. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce AW, Sunderland VB, Burrows S, McManus A, Howat P, Maycock B. Community pharmacy's role in promoting healthy behaviours. J Pharm Pract Res. 2007;37(1):42–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel HR. Is there a future for community pharmacy in public health? Pharm J. 2002;269:741. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pike H. Pharmaceutical program for public health- priorities for the next decade. Pharm J. 2005;274(April 9):417–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A, Armstrong M. Pharmacists' perceptions regarding their contribution to improving the public's health: a systematic review of the United Kingdom and international literature 1990–2001. Int J Pharm Pract. 2003;11(2):111–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford SY. Pharmacists' roles in health promotion and disease prevention. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(4):69. Article 73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fincham JE. Public health, pharmacy, and the Prevention Education Resource Center (PERC) Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5) doi: 10.5688/aj7105104. Article 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document/pdf/Volume2/17Medical.pdf Accessed October 20, 2009.

- 17.Merican MI, bin Yon R. Health care reform and changes: the Malaysian experience. Asia Pacific J Pub Health. 2002;14(1):17–22. doi: 10.1177/101053950201400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmona RH. Healthy people curriculum task force: a commentary by the surgeon general. Am J Prev Med. Dec 2004;27(5):478–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ab Rahman AF, Ibrahim MI, Bahari MB, Nik Mohamed MH, Awang R. Design and evaluation of the pharmacoinformatics course at a pharmacy school in Malaysia. Drug Inf J. 2002;36(4):783–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim MI, Awang R, Abdul Razak D. Introducing social pharmacy courses to pharmacy students in Malaysia. Med Teach. 1998;20(2):122–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark B. Growing Up Gifted: Developing the Potential of Children at Home and at School. Upper Saddle River: Merrille Prentice Hall; 2002. [Google Scholar]