Abstract

Background & Aims

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection may reactivate in the setting of immune suppression, although the frequency and consequences of HBV reactivation are not well known. We report six patients who experienced loss of serologic markers of hepatitis B immunity and reappearance of Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the serum due to a variety of acquired immune deficiencies.

Methods

Between 2000 and 2005, six patients with reactivation of hepatitis B were seen in consultation by the Liver Diseases Branch at the Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health. The course and outcome of these six patients were reviewed.

Results

All six patients developed reappearance of HBsAg and evidence of active liver disease after stem cell transplantation (n=4), immunosuppressive therapy (n=1) or change in HIV antiretroviral regimen (n=1) despite having antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs) or antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) without HBsAg before. All six patients developed chronic hepatitis B, two patients transmitted hepatitis B to their spouses, and one patient developed cirrhosis. The diagnosis of hepatitis B reactivation was frequently missed or delayed and often required interruption of the therapy for the underlying condition. None of the patients received antiviral prophylaxis against HBV reactivation.

Conclusions

Serologic evidence of recovery from hepatitis B infection does not preclude its reactivation after immunosuppression. Screening for serologic evidence of hepatitis B and prophylaxis of those with positive results using nucleoside analogue antiviral therapy should be provided to individuals in whom immunosuppressive therapy is planned.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, hepatitis B surface antigen, antibody to hepatitis B core antigen, immunocompromise, complications of chemotherapy, stem cell transplantation, reverse seroconversion

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B is one of the most common viral infections, affecting an estimated 6% of the world population.1 Each year, an estimated one million persons die of complications of chronic HBV infection, including cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma.2 Chronic infection with HBV is usually defined by the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) detected on at least two occasions spaced no fewer than six months apart, with variable amounts of HBV DNA in serum; recovery and immunity to hepatitis B are marked by antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) with or without antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs), in the absence of HBsAg. The course and outcome of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is modulated by the host immune response, and the loss of immune surveillance can cause reactivation of viral replication and exacerbations of disease activity.3-6 In the profoundly immunocompromised individual, HBV may reactivate even in the presence of serologic evidence of resolved infection.7 The loss of anti-HBs followed by reactivation with development of HBsAg is known as reverse seroconversion.

Some immunosuppressive therapies may enhance HBV viral replication in hepatocytes6, 8, 9 at the same time as they curb host immune responses, resulting in detectable viremia followed by clinical hepatitis.3 In such a vulnerable host, HBV can result in fulminant hepatitis and death.10

Anticipation of these events is the key to protecting patients from the sequelae of HBV reactivation. To this end, we present cases of six immunocompromised patients referred to and followed by the NIH Clinical Center's hepatology consultation service. Each case, described below and summarized in Table 1, illustrates the need to preempt the re-establishment of active HBV infection.

Table 1. Summary of Clinical Data from Cases in this Series.

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case # | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | HBsAg | anti HBs | anti HBc | HBV DNA | Intervention | Time to Reactivation | HBsAg | anti HBs | anti HBc | HBV DNA | Outcome |

| 1 | 45 | M | CML | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Stem cell transplantation | 6-20 months | Pos | Neg | Neg | Detected | Chronic hepatitis, possible cirrhosis, death from sepsis |

| 2 | 56 | F | CML | Not done | Pos | Not done | Not done | Stem cell transplantation | < 2 years | Pos | Neg | Detected | Chronic hepatitis | |

| 3 | 49 | M | CML | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Stem cell transplantation | < 29 months | Pos | Neg | Neg | Detected | Serologic resolution |

| 4 | 46 | M | HIV | Neg | Neg | Pos | Negative | Lamivudine withdrawal | 5 months | Pos | Neg | Not done | Detected | Unknown |

| 5 | 45 | M | SAA | Neg | Pos | Neg | Not done | anti-thymocyte globulin | Uncertain | Pos | Neg | Pos | Not done | Serologic resolution |

| 6 | 54 | F | Multiple myeloma | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Stem cell transplantation | 4 years | Pos | Neg | Not done | Detected | Chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, death from variceal bleeding |

CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkins lymphoma; PCKD, polycystic kidney disease

Case Reports

Case 1

A 45-year-old Ethiopian-born physician with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) for 12 years was evaluated for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. His serum was HBsAg negative, but positive for both anti-HBs and anti-HBc. He denied a history of jaundice or hepatitis, blood transfusions, alcohol or drug use. He had received hepatitis B vaccine during medical school.

He underwent a T-cell-depleted, myeloablative stem cell transplantation in June 2001 from his sister, a 6/6 HLA match who tested negative for all markers of HBV infection. The immediate post-transplantation period was complicated by a brief episode of neutropenic fever and giardiasis. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were mildly and transiently elevated (40-50 U/L: normal <41 U/L).

In the 18 months following transplantation, he underwent two donor lymphocyte infusions, was admitted to the hospital six times for infections, and was given aggressive immunosuppressive therapy, including prednisone, sirolimus, tacrolimus, cyclosporine A, and dacluzimab, for severe graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) involving the skin and intestine. He had local relapses of CML in the knee (March 2002) and shoulder (October 2002) and was retreated with imatinib, a chemotherapeutic agent which inhibits tyrosine kinase.

Six months after transplantation, serum ALT levels rose to the mid-400s and then returned to normal over several weeks. The abnormalities were attributed to liver involvement by GVHD. In February 2003, the patient's 40-year-old wife, also Ethiopian born, presented to her physician with fevers, chills, nausea, and abdominal pain. Serum testing revealed an ALT of 376 U/L as well as HBsAg and IgM anti-HBc. She subsequently recovered and had normal ALT levels with anti-HBs and no detectable HBsAg in serum. At this point, her husband was tested and found to be reactive for HBsAg, HBeAg and HBV DNA (1.96 × 108/ml) despite normal serum aminotransferase levels and absence of anti-HBc. The patient developed clinical features of cirrhosis and died three years later of bacterial sepsis. The patient developed clinical features of cirrhosis and died three years later of bacterial sepsis.

Case 2

A 56 year-old woman underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation for CML in 1998. She tested positive for anti-HBs before transplantation, but was not tested for HBsAg, HBV DNA or anti-HBc. The stem cell donor was HBsAg negative but was not tested for anti-HBs or anti-HBc. After transplantation, the patient had intermittent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and ALT. Two years later she was tested for markers of HBV infection and was persistently positive for HBsAg and HBeAg although serum ALT levels gradually fell to normal. In 2003, her 65 year-old husband developed acute hepatitis B with serum bilirubin rising to 4.8 mg/dL. He had detectable HBsAg and IgM anti-HBc. Because of persistent ALT elevations and HBV DNA, he was started on lamivudine (100 mg daily) and slowly improved. Serum ALT levels ultimately fell into the normal range and HBsAg became undetectable. After the episode of acute hepatitis in her husband, further testing was done on the transplant recipient, which showed intermittently elevated ALT levels with persistence of HBsAg and HBV DNA level of 4.2 × 107 IU/ml. The patient was started on entecavir 0.5 mg once daily. She responded well and had normalization of serum ALT and undetectable HBV DNA levels over a period of one year.

Case 3

A 49-year-old man from Pakistan was diagnosed with CML in August 1999 and received a stem cell transplant from his sister in October 2000. Before transplantation, serological testing showed the absence of HBsAg but presence of anti-HBs and anti-HBc. The donor possessed a similar serologic profile.

After transplantation, the patient had multiple complications including CMV colitis, radiation pneumonitis, and GVHD involving the skin and gut for which he received prednisone and cyclosporine A. One year after transplantation, while receiving immunosuppressive therapy with prednisone and cyclosporine A for chronic GVHD, he tested negative for HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc. At two years, he developed elevations in serum ALT that were attributed to GVHD involvement of the liver, and was treated empirically with tacrolimus for eight months. Five months into this therapy, evaluation revealed a newly detectable HBsAg, undetectable anti-HBs and anti-HBc, and a high level of HBV DNA (6.8 × 105 IU/ml).

Case 4

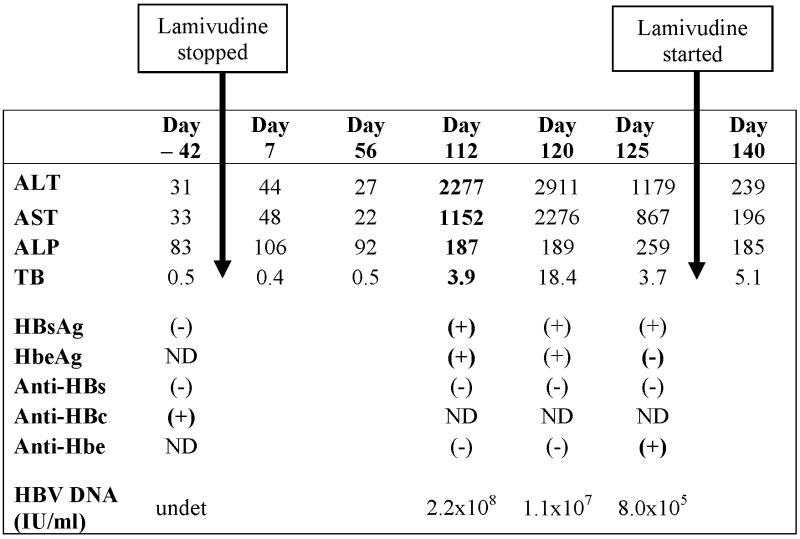

A 46-year-old man with HIV infection diagnosed in 1988 presented in August 1999 with a week of fever, nausea and vomiting, fatigue, generalized pruritus, abdominal discomfort, and tea-colored urine. His antiretroviral medications had been changed three months before from a lamivudine-containing regimen to abacavir, efavirenz, amprenavir, and ritonavir because of elevated HIV viral load and evidence of lamivudine-resistant HIV. His absolute CD4+ lymphocyte count was 770. He had a history of icteric hepatitis B in 1970. His serum ALT was 2277 U/L and bilirubin 3.9 mg/dL. He was positive for HBsAg and HBeAg and HBV DNA levels were 1.1 billion copies/mL. Five months previously, before lamivudine had been stopped, he had normal serum aminotransferase levels and tested positive for anti-HBc without detectable HBsAg or anti-HBs (Table 2). A stored serum specimen from that time was available and tested negative for HBV DNA. Lamivudine was restarted and he had rapid improvement in symptoms and serum aminotransferase and bilirubin elevations, and his HBV DNA became undetectable for the following two years, after which he was lost to followup.

Table 2. Hepatic chemistries and hepatitis B serologic studies from Case 4.

|

Case 5

A 42-year-old man from the Dominican Republic presented in 2003 with severe aplastic anemia. Serum aminotransferase levels were normal. He had detectable anti-HBs without HBsAg or anti-HBc, but no history of HBV vaccination. He was treated with antithymocyte globulin, followed by cyclosporine and mycophenolate for several months. He improved initially but redeveloped pancytopenia one year later. At this point, serum aminotransferase levels were elevated and repeat testing showed HBsAg, HBeAg and anti-HBc without anti-HBs.

Case 6

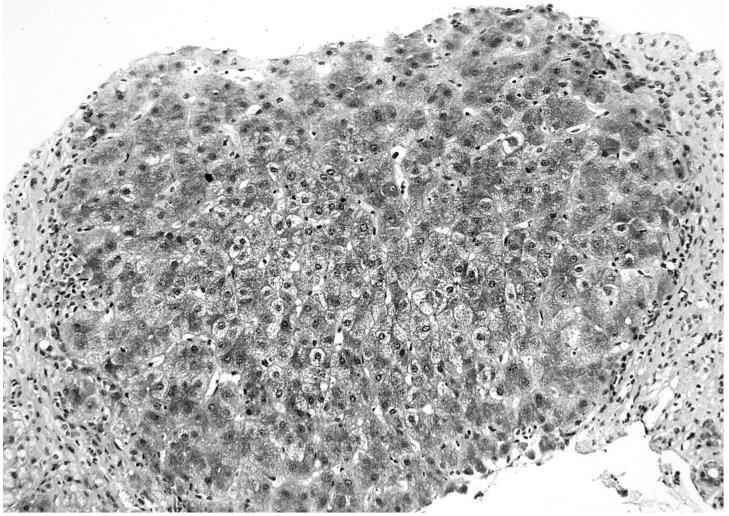

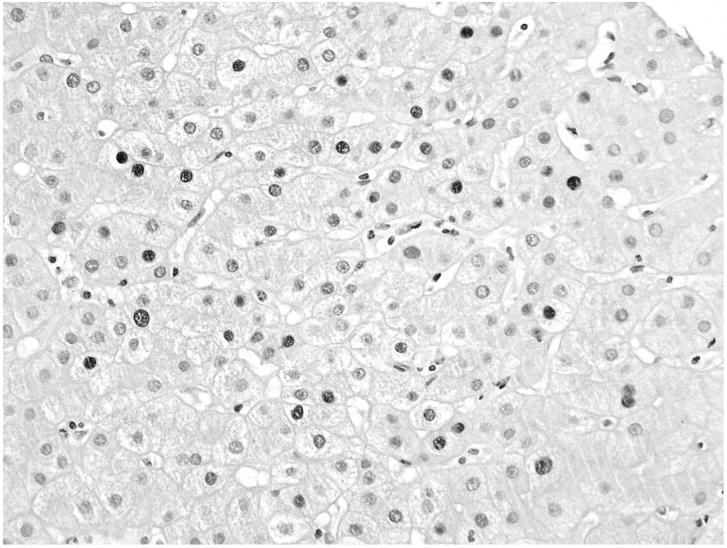

A 54-year-old Jamaican woman underwent an allogeneic stem cell transplant for multiple myeloma in November 2000. Her course was complicated by recurrent bouts of skin and gastrointestinal GVHD, for which she was treated with corticosteroids and tacrolimus. Before transplantation, she had anti-HBs and anti-HBc, without HBsAg in serum. Her sister, the donor, had no detectable HBsAg, anti-HBs or anti-HBc. After transplantation, the patient had intermittent elevations in serum ALT (peak 162 U/L) which were attributed to GVHD and managed with immunosuppressive therapy. Four years after transplantation, she developed ankle edema and ascites. Serum ALT was 70 U/L, total bilirubin 1.7 g/dL, albumin 2.9 g/L, and prothrombin time 15 seconds. At this point, she was found to have HBsAg and HBeAg in serum and an HBV DNA level of 2.2 × 108 IU/ml. A liver biopsy showed moderate portal and parenchymal inflammation with established cirrhosis and no evidence of GVHD (Figures 1 and 2). She subsequently died as a consequence of esophageal variceal hemorrhage.

Figure 1.

A needle liver biopsy from patient 6 showing established cirrhosis with a regenerative nodule surrounded by fibrosis. Masson stain 20×.

Figure 2.

Liver biopsy from patient 6 showing hepatic parenchyma stained with anti-HBc. Affected nuclei are positively stained and appear darker. 40×.

Discussion

The host immune response plays a major role in the course and outcome of acute HBV infection. Thus, most adults with acute HBV infection recover uneventfully, and probably fewer than 5% fail to clear HBsAg and develop chronic hepatitis B.11 In contrast, newborns and immunocompromised adults usually do not recover, but develop chronic infection with variable degrees of chronic inflammation and injury.12 Persons with acute HBV infection who recover often have symptomatic and icteric disease, while those with acute infection who evolve into chronic hepatitis typically have subclinical, anicteric disease and may not be aware of having acquired the infection.12

Although patients who clear HBsAg and HBV DNA from serum are often referred to as having ‘recovered’ from HBV infection, this is a misnomer. In such cases the immune system has successfully suppressed viral replication, however HBV persists in the liver, and possibly in other tissues. Small quantities of HBV remain in infected cells in a form known as covalently closed circular or cccDNA. This is an episomal form of the viral genome, which intermittently can become transcriptionally active. With normal immune function, viral replication is immediately suppressed by circulating HBV-specific immune cells. However if immune surveillance is lost, due to either natural or treatment-induced immunosuppression, HBV can once again replicate with the potential for chronic liver damage and, as shown here, disease transmission. Indeed, molecular analysis of liver tissue from patients who have recovered from acute or chronic hepatitis B has revealed the presence of low levels of HBV DNA in liver.13-17 Most convincing for the persistence of HBV despite recovery, however, have been the “experiments in nature,” including liver and stem cell transplantation. Patients without hepatitis B who receive a donor liver from a person with serological markers of recovery from hepatitis B (anti-HBc with or without anti-HBs but with no detectable HBsAg or HBV DNA in serum) almost invariably develop hepatitis B after transplantation.18-21 The source of the hepatitis B appears to be the donor liver graft rather than a pre-existing “occult” hepatitis B in the recipient. For these reasons, donors with anti-HBc are generally excluded from use, although studies have shown that these livers can be used if prophylaxis is given against reactivation of hepatitis B or if the liver is given to a patient who has pre-existing hepatitis B infection.22-26

HBV reactivation can also occur due to “escape” mutants, which can cause clinical hepatitis in the presence of anti-HBs because of a mutation in the major antigenic determinant of the HBsAg.27 None of our cases suggested this phenomenon.

Stem cell transplantation represents the converse of liver transplantation in regards to reactivation of hepatitis B. In stem cell transplantation, the source of the hepatitis B is not the donor graft but rather the liver of the stem cell transplant recipient.4, 6, 28-32 In this situation, the profound immunosuppression and loss of pre-existing HBV-specific immunity allows for HBV reactivation in the recovered liver and return of active viral replication. Because stem cell and liver transplant patients receive long-term immunosuppressive therapy, they are prone to develop chronic infection once the virus is reactivated.18, 20, 33 Reactivation after stem cell transplantation is actually an extreme example of reactivation that can occur with any form of severe immunosuppression, such as with chemotherapy for leukemia or solid tumors,3, 10, 34-36 immunomodulation in autoimmune disease,37-39 and spontaneously with progression of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome5, 7, 40-43 (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of Clinical Data from Published Case Reports of HBV Reverse Seroconversiona.

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | HBsAg | anti HBs | anti HBc | HBV DNA | Intervention | Time to Reactivation | HBsAg | anti HBs | anti HBc | HBV DNA | Outcome |

| Wands et al.52 | 21 | M | AML | Neg | Pos | Not done | Not done | Cytotoxic chemo | 2 mos | Pos | Neg | Not done | Not done | Serologic resolution |

| Chen et al.55 | 35 | F | SAA | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 12 mos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Not done | Active/N.S.b |

| Lok35 | N.S. | M | NHL | Neg | Pos | Pos | Negative | Cytotoxic chemoc | N/A | Pos | Neg | N.S.b | Detected | Carrier state |

| Dhedin et al.56 | 38 | M | CML | Neg | Pos | Not done | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 12 mos | Pos | Neg | pos | Detected | Serologic resolution |

| Dhedin et al.56 | 44 | M | AML | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 10 mos | Pos | Neg | pos | Detected | Hepatitis/N.S. b |

| Dhedin et al.56 | 44 | M | SAA | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 6 mos | Pos | Neg | pos | Detected | Serologic resolution |

| Dhedin et al.56 | 46 | M | ALL | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 18 mos | Pos | Neg | pos | Detected | Serologic resolution |

| Goyama60 | 59 | M | Acute Leukemia | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 6 mos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Detected | Serologic resolution |

| Goyama60 | 52 | M | CML | Neg | Pos | Pos | Negative | Bone Marrow Transp | 11 mos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Detected | Serologic resolution |

| Knoll et al.59 | 41 | M | ALL | Neg | Pos | Pos | Detected | Bone Marrow Transp | 14 mos | Pos | Neg | pos | Detected | Serologic resolution |

| Knoll et al.59 | 55 | M | CML | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 22 mos | Pos | Neg | pos | Detected | Carrier state |

| Knoll et al.59 | 51 | M | CML | Neg | Pos | Not done | Detected | Bone Marrow Transp | 12 mos | Pos | Neg | Not done | Detected | Carrier state |

| Iannitto et al.61 | 60 | F | CLL | Neg | Pos | Pos | Detected | Alemtuzumab | 4 weeks | Pos | Neg | Pos | Detected | Serologic resolution |

| Berger et al.62 | 75 | M | PCKD | Neg | Pos | Pos | Negative | Renal transplant | 5 yrs | Pos | Neg | Pos | Detected | N.S. b |

| Kempinska63 | 47 | M | AML | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 17 months | Pos | Neg | Pos | Detected | Chronic hepatitis |

| Gwak et al.37 | 66 | F | Rheum Arthritis | Neg | Pos | Not done | Negative | Methotrexate | 7 yrs | Pos | Neg | Neg | Detected | Fulminant liver failure, death |

| Awerkiew et al.64 | 36 | M | NHL | Neg | Pos | Neg | Not done | Cytotoxic Chemo | 5 yrs | Pos | Pos | Neg | Detected | Death |

| Giudice et al.65 | 13 | M | AML | Neg | Pos | Pos | Detected | Bone Marrow Transp | 6 mos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Detected | Chronic hepatitis |

| Oshima et al.66 | 42 | F | ALL | Neg | Pos | Pos | Not done | Bone Marrow Transp | 23 mos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Detected | Serologic resolution |

Published case series not included because they do not present individual-level clinical data57: Seth et al.,57 Onozawa et al.,58 Uhm et al.54

N.S., not specified

Reverse seroconversion occurred prior to chemotherapy

CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkins lymphoma; PCKD, polycystic kidney disease

The six cases presented in this report represent the spectrum of manifestations, underlying conditions and outcomes of reactivation with reappearance of HBsAg. The risk of reactivation probably relates both to the degree of immune suppression (being profound after stem cell transplantation and of mild to moderate severity with chemotherapy and use of immunomodulatory agents) as well as the state of HBV replication in the liver. Thus, reactivation or at least an increase in viral replication can be expected in most persons who are HBsAg positive and have low levels of HBV DNA in serum.10, 35, 44 Several studies have shown that patients with HBsAg and inactive liver disease can suffer severe clinical reactivation of hepatitis B after cancer chemotherapy and many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of prophylaxis with nucleoside analogue anti-HBV therapy against such reactivation.44-51 Reactivation with reappearance of HBsAg is less common after standard chemotherapy for cancer, but can occur35, 52, 53 and is probably even more frequent with more rigorous forms of immune suppression such as stem cell transplantation (in which the immune system that has successfully held HBV replication under control is ablated and a donor immune system is substituted).54-59

Four cases, #1,#2,#3 & #6, were examples of reactivation with reappearance of HBsAg in recipients of stem cell transplants. In each case, the recipient had serological markers of previous HBV infection before transplant; whereas only one of the donors had such serological markers. The onset of the reactivation was minimally or not symptomatic and all four patients were found to have become HBsAg and HBV DNA positive almost incidentally, either from routine testing or, in two instances, after spouses developed acute, self-limited hepatitis B infection. In all four cases, the recurrent hepatitis B became chronic and in one instance the recurrent disease was severe and progressive, leading to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease and death within 4 years of the stem cell transplant. In all four, HBV DNA levels were high and sustained, even though immunosuppression was given only intermittently in most cases.

One case (5) represented reactivation caused by marked immune suppression from therapy (antithymocyte globulin, cyclosporine and mycophenolate) for aplastic anemia. He was found to have chronic hepatitis B when serum aminotransferase levels were persistently elevated approximately two years after initial immunosuppressive therapy. Notably this patient was initially positive only for anti-HBs, having presumably lost anti-HBc over time. This highlights the importance of considering ‘recovered’ HBV infection in patients who are positive for only anti-HBs but have no history of HBV vaccination. This is particularly relevant in patients from areas with high HBV prevalence.

Finally, in one case, #4, reactivation with reappearance of HBsAg occurred in a patient with HIV infection and progressive immunodeficiency. In this patient, hepatitis B was not suspected and the disease arose when lamivudine therapy was withdrawn as a part of the routine modification of drug regimens in managing chronic HIV infection. This instance reinforces the need to provide anti-HBV activity in the antiretroviral regimen in patients with anti-HBc even in the absence of HBsAg. Alternatives to lamivudine in this situation include tenofovir and emtracitabine. Other antiretroviral agents have little or no activity against HBV.

These six examples of reactivation and reappearance of HBsAg in patients with serological evidence of previous infection underscore the need to screen patients routinely for markers of HBV infection before embarking upon chemotherapy or immune suppression as in stem cell or even solid organ transplantation. Because the onset of recurrent hepatitis B can be subclinical and insidious, this problem may not always be apparent and the consequences of the reactivation may not appear until long after the patient is no longer followed for the treatment of cancer or autoimmune disease. Routine testing should include anti-HBc, HBsAg and anti-HBs, as patients with immune deficiencies may lose antibody reactivity to HBV antigens. Patients with markers of previous HBV infection should receive prophylaxis using either lamivudine or other anti-HBV nucleoside analogues (adefovir, tenofovir, emtracitabine, telbivudine, or entecavir). The duration of such antiviral prophylaxis has not been defined, but therapy may be needed life long in the situation of sustained immune alteration such as stem cell transplantation. Prospective studies of prophylaxis in these situations are needed, not to demonstrate so much the need for prophylaxis as the optimal antiviral regimen and whether prophylaxis can safely be stopped. Sex partners and close household contacts of patients with markers of previous HBV infection who are at risk for reverse seroconversion should be screened and preemptively vaccinated against HBV.

Conclusion

We present six cases of HBV reactivation in patients at a single institution seen over a five-year period. Five patients experienced reverse seroconversion after immunosuppressive therapy, and one experienced reactivation after withdrawal of nucleoside analogue therapy. These cases exemplify the need to provide prophylaxis against hepatitis B reactivation in immunocompromised patients. They illustrate the importance of proper screening of transplant recipients and donors, and others who face a period of immunosuppression. Patients with antibodies to HBV not as a result of vaccination should be regarded as harboring HBV in liver and monitored for reactivation. Immunocompromised patients stopping effective nucleoside analogs should be monitored closely for withdrawal flares even if they do not have detectable HBsAg. Finally, it is reasonable to suggest that stem cell donors without detectable anti-HBs be vaccinated, when possible, prior to harvesting of the transplant.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patients for their ability to teach and humble us. In memory of patients 1 and 6.

Financial support: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the NIDDK (Z01 DK054514-02), NIAID, NHLBI, and NCI, NIH.

Abbreviations

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- CML

chronic myelogenous leukemia

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- anti-HBs

antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen

- anti-HBc

antibody to hepatitis B core antigen

- GVHD

graft-versus-host disease

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McMahon BJ. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25 1:3–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. 2004:2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xunrong L, Yan AW, Liang R, Lau GK. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation after cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy--pathogenesis and management. Rev Med Virol. 2001;11:287–99. doi: 10.1002/rmv.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen PM, Fan S, Liu JH, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus in two chronic GVHD patients after transplant. Int J Hematol. 1993;58:183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laukamm-Josten U, Muller O, Bienzle U, Feldmeier H, Uy A, Guggenmoos-Holzmann I. Decline of naturally acquired antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen in HIV-1 infected homosexual men. AIDS. 1988;2:400–1. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198810000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romand F, Michallet M, Pichoud C, Trepo C, Zoulim F. Hepatitis B virus reactivation after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in a patient previously cured of hepatitis B. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:770–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waite J, Gilson RJ, Weller IV, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation or reinfection associated with HIV-1 infection. Aids. 1988;2:443–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198812000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMillan JS, Shaw T, Angus PW, Locarnini SA. Effect of immunosuppressive and antiviral agents on hepatitis B virus replication in vitro. Hepatology. 1995;22:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tur-Kaspa R, Laub O. Corticosteroids stimulate hepatitis B virus DNA, mRNA and protein production in a stable expression system. J Hepatol. 1990;11:34–6. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90268-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoofnagle JH, Dusheiko GM, Schafer DF, et al. Reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection by cancer chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:447–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-4-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B virus infection--natural history and clinical consequences. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1118–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perillo R, Nair S. Hepatitis B and D. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors. Sleisenger & Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 8th. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 1647–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehermann B, Ferrari C, Pasquinelli C, Chisari FV. The hepatitis B virus persists for decades after patients' recovery from acute viral hepatitis despite active maintenance of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response. Nat Med. 1996;2:1104–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brechot C, Degos F, Lugassy C, et al. Hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with chronic liver disease and negative tests for hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:270–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501313120503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iizuka H, Ohmura K, Ishijima A, et al. Correlation between anti-HBc titers and HBV DNA in blood units without detectable HBsAg. Vox Sang. 1992;63:107–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1992.tb02495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoofnagle JH, Gerety RJ, Ni LY, Barker LF. Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. A sensitive indicator of hepatitis B virus replication N Engl J Med. 1974;290:1336–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197406132902402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang TJ, Baruch Y, Ben-Porath E, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in patients with idiopathic liver disease. Hepatology. 1991;13:1044–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roche B, Samuel D, Gigou M, et al. De novo and apparent de novo hepatitis B virus infection after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 1997;26:517–26. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chazouilleres O, Mamish D, Kim M, et al. “Occult” hepatitis B virus as source of infection in liver transplant recipients. Lancet. 1994;343:142–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90934-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickson RC, Everhart JE, Lake JR, et al. Transmission of hepatitis B by transplantation of livers from donors positive for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Liver Transplantation Database. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1668–74. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wachs ME, Amend WJ, Ascher NL, et al. The risk of transmission of hepatitis B from HBsAg(-), HBcAb(+), HBIgM(-) organ donors. Transplantation. 1995;59:230–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loss GE, Mason AL, Blazek J, et al. Transplantation of livers from hbc Ab positive donors into HBc Ab negative recipients: a strategy and preliminary results. Clin Transplant. 2001;15 6:55–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2001.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holt D, Thomas R, Van Thiel D, Brems JJ. Use of hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors in orthotopic liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 2002;137:572–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.5.572. discussion 5-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prakoso E, Strasser SI, Koorey DJ, Verran D, McCaughan GW. Long-term lamivudine monotherapy prevents development of hepatitis B virus infection in hepatitis B surface-antigen negative liver transplant recipients from hepatitis B core-antibody-positive donors. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:369–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nery JR, Nery-Avila C, Reddy KR, et al. Use of liver grafts from donors positive for antihepatitis B-core antibody (anti-HBc) in the era of prophylaxis with hepatitis-B immunoglobulin and lamivudine. Transplantation. 2003;75:1179–86. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000065283.98275.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joya-Vazquez PP, Dodson FS, Dvorchik I, et al. Impact of anti-hepatitis Bc-positive grafts on the outcome of liver transplantation for HBV-related cirrhosis. Transplantation. 2002;73:1598–602. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kajiwara E, Tanaka Y, Ohashi T, et al. Hepatitis B caused by a hepatitis B surface antigen escape mutant. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:243–7. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwai K, Tashima M, Itoh M, et al. Fulminant hepatitis B following bone marrow transplantation in an HBsAg-negative, HBsAb-positive recipient; reactivation of dormant virus during the immunosuppressive period. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:105–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senecal D, Pichon E, Dubois F, Delain M, Linassier C, Colombat P. Acute hepatitis B after autologous stem cell transplantation in a man previously infected by hepatitis B virus. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:1243–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin BA, Rowe JM, Kouides PA, DiPersio JF. Hepatitis B reactivation following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webster A, Brenner MK, Prentice HG, Griffiths PD. Fatal hepatitis B reactivation after autologous bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1989;4:207–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aubourg A, d'Alteroche L, Senecal D, Gaudy C, Bacq Y. Autoimmune thrombopenia associated with hepatitis B reactivation (reverse seroconversion) after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31:97–9. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(07)89335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanpain C, Knoop C, Delforge ML, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B after transplantation in patients with pre-existing anti-hepatitis B surface antigen antibodies: report on three cases and review of the literature. Transplantation. 1998;66:883–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. Lamivudine therapy for chemotherapy-induced reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:249–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, Wong KL, Chan TK, Todd D. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. Report of a prospective study Gastroenterology. 1991;100:182–8. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90599-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Law JK, Ho JK, Hoskins PJ, Erb SR, Steinbrecher UP, Yoshida EM. Fatal reactivation of hepatitis B post-chemotherapy for lymphoma in a hepatitis B surface antigen-negative, hepatitis B core antibody-positive patient: potential implications for future prophylaxis recommendations. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1085–9. doi: 10.1080/10428190500062932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gwak GY, Koh KC, Kim HY. Fatal hepatic failure associated with hepatitis B virus reactivation in a hepatitis B surface antigen-negative patient with rheumatoid arthritis receiving low dose methotrexate. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:888–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostuni P, Botsios C, Punzi L, Sfriso P, Todesco S. Hepatitis B reactivation in a chronic hepatitis B surface antigen carrier with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab and low dose methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:686–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.7.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai FC, Hsieh SC, Chen DS, Sheu JC, Chen CH. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus in rheumatologic patients receiving immunosuppressive agents. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1627–32. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altfeld M, Rockstroh JK, Addo M, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B in a long-term anti-HBs-positive patient with AIDS following lamivudine withdrawal. J Hepatol. 1998;29:306–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chamorro AJ, Casado JL, Bellido D, Moreno S. Reactivation of hepatitis B in an HIV-infected patient with antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen as the only serological marker. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:492–4. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazizi Y, Grangeot-Keros L, Delfraissy JF, et al. Reappearance of hepatitis B virus in immune patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:666–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ, Hoofnagle J. Accelerated loss of antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen among immunodeficient homosexual men infected with HIV. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:630–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703053161015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau GK, Yiu HH, Fong DY, et al. Early is superior to deferred preemptive lamivudine therapy for hepatitis B patients undergoing chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1742–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeo W, Hui EP, Chan AT, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma with lamivudine. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:379–84. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000159554.97885.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rossi G. Prophylaxis with lamivudine of hepatitis B virus reactivation in chronic HbsAg carriers with hemato-oncological neoplasias treated with chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:759–66. doi: 10.1080/104281903100006351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dai MS, Wu PF, Shyu RY, Lu JJ, Chao TY. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in breast cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy and the role of preemptive lamivudine administration. Liver Int. 2004;24:540–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Idilman R, Arat M, Soydan E, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis for prevention of chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B virus carriers with malignancies. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:141–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shibolet O, Ilan Y, Gillis S, Hubert A, Shouval D, Safadi R. Lamivudine therapy for prevention of immunosuppressive-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B surface antigen carriers. Blood. 2002;100:391–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loomba R, Rowley A, Wesley R, et al. Systematic review: the effect of preventive lamivudine on hepatitis B reactivation during chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:519–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-7-200804010-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohrt HE, Ouyang DL, Keeffe EB. Systematic review: lamivudine prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1003–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wands JR, Chura CM, Roll FJ, Maddrey WC. Serial studies of hepatitis-associated antigen and antibody in patients receiving antitumor chemotherapy for myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mindikoglu AL, Regev A, Schiff ER. Hepatitis B virus reactivation after cytotoxic chemotherapy: the disease and its prevention. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1076–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uhm JE, Kim K, Lim TK, et al. Changes in serologic markers of hepatitis B following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:463–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen PM, Fan S, Liu CJ, et al. Changing of hepatitis B virus markers in patients with bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1990;49:708–13. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dhedin N, Douvin C, Kuentz M, et al. Reverse seroconversion of hepatitis B after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective study of 37 patients with pretransplant anti-HBs and anti-HBc. Transplantation. 1998;66:616–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199809150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seth P, Alrajhi AA, Kagevi I, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation with clinical flare in allogeneic stem cell transplants with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30:189–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Onozawa M, Hashino S, Izumiyama K, et al. Progressive disappearance of anti-hepatitis B surface antigen antibody and reverse seroconversion after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with previous hepatitis B virus infection. Transplantation. 2005;79:616–9. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000151661.52601.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knoll A, Boehm S, Hahn J, Holler E, Jilg W. Reactivation of resolved hepatitis B virus infection after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:925–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goyama S, Kanda Y, Nannya Y, et al. Reverse seroconversion of hepatitis B virus after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:2159–63. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000033042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iannitto E, Minardi V, Calvaruso G, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and alemtuzumab therapy. Eur J Haematol. 2005;74:254–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berger A, Preiser W, Kachel HG, Sturmer M, Doerr HW. HBV reactivation after kidney transplantation. J Clin Virol. 2005;32:162–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kempinska A, Kwak EJ, Angel JB. Reactivation of hepatitis B infection following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in a hepatitis B-immune patient: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1277–82. doi: 10.1086/496924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Awerkiew S, Daumer M, Reiser M, et al. Reactivation of an occult hepatitis B virus escape mutant in an anti-HBs positive, anti-HBc negative lymphoma patient. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:83–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giudice CL, Martinengo M, Pietrasanta P, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: a case of reactivation in a patient receiving immunosuppressive treatment for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood Transfus. 2008;6:46–50. doi: 10.2450/2008.0033-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oshima K, Sato M, Okuda S, et al. Reverse seroconversion of hepatitis B virus after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the absence of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Hematology. 2009;14:73–5. doi: 10.1179/102453309X385223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]