Abstract

Objective

Despite the increased emphasis on obesity and diet-related diseases, nutrition education remains lacking in many internal medicine training programs. We evaluated the attitudes, self-perceived proficiency, and knowledge related to clinical nutrition among a cohort of internal medicine interns.

Methods

Nutrition attitudes and self-perceived proficiency were measured using previously validated questionnaires. Knowledge was assessed with a multiple-choice quiz. Subjects were asked whether they had prior nutrition training.

Results

Of the 114 participants, 61 (54%) completed the survey. Although 77% agreed that nutrition assessment should be included in routine primary care visits, and 94% agreed that it was their obligation to discuss nutrition with patients, only 14% felt physicians were adequately trained to provide nutrition counseling. There was no correlation among attitudes, self-perceived proficiency, or knowledge. Interns previously exposed to nutrition education reported more negative attitudes toward physician self-efficacy (p = 0.03).

Conclusions

Internal medicine interns’ perceive nutrition counseling as a priority, but lack the confidence and knowledge to effectively provide adequate nutrition education.

INTRODUCTION

The most recent NHANES data released in April 2006 revealed that approximately two-thirds of US adults are over-weight or obese, with significant increases in the prevalence of obesity among men, children and adolescents [1]. Obesity-related diseases including diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, hypertension, and certain cancers are among the leading causes of death in the US [2,3]. Given its’ epidemic proportions, obesity has emerged as one of our nation’s most important public health challenges. More and more, the primary care provider is expected to be a key player in tackling this battle, especially given data suggesting that patients consider physicians to be one of the most credible sources of nutrition information [4]. However, less than half of primary care physicians routinely discuss weight loss with obese patients or provide dietary counseling [4,5]. Why? Although lack of time and lack of patient compliance are the most commonly perceived barriers, 67% of physicians report lack of training in counseling skills and 62% report deficits of knowledge about nutrition as major barriers [4]. Physicians do, however, hold positive views about the importance of nutrition [4,6]. The need for nutrition education for physicians, therefore, has never been more urgent.

Within recent years, nutrition has emerged as an important topic in medical education. In 1997, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute created the Nutrition Academic Award (NAA) in an effort to develop innovative strategies for nutrition education for medical students. Twenty-one medical schools have been recipients of the award since that time [7]. Although more material on nutrition has been integrated into medical school curricula since the inception of the NAA, 51.1% of US medical school graduates in 2005 (compared to 64.4% in 1998) still reported that they received inadequate nutrition education during their undergraduate medical training [8]. Although fewer studies are available, it appears that training in nutrition during residency is even more deficient [9]. This trend is concerning, as medical students’ interest and enthusiasm in nutrition education has been found to wane rapidly in the absence of reinforcement from their clinical house staff and faculty mentors, who also feel inadequate in their own nutrition knowledge and counseling skills [4,10].

To guide the design of an effective nutrition curriculum for residents, we performed a targeted needs assessment to determine the attitudes, self-perceived proficiency, and knowledge related to nutrition and obesity among internal medicine interns. Although prior studies have reported on the relationship between nutrition attitudes and knowledge [11-13], results have been equivocal and there are no studies examining the correlations among attitudes, self-perceived proficiency, and knowledge. This study seeks to further elucidate these relationships.

METHODS

Subjects

We anonymously surveyed 114 internal medicine interns (64 incoming interns and 50 current interns) from a university-based internal medicine training program to evaluate their attitudes, self-perceived proficiency, and knowledge about clinical nutrition.

Survey Instrument and Administration

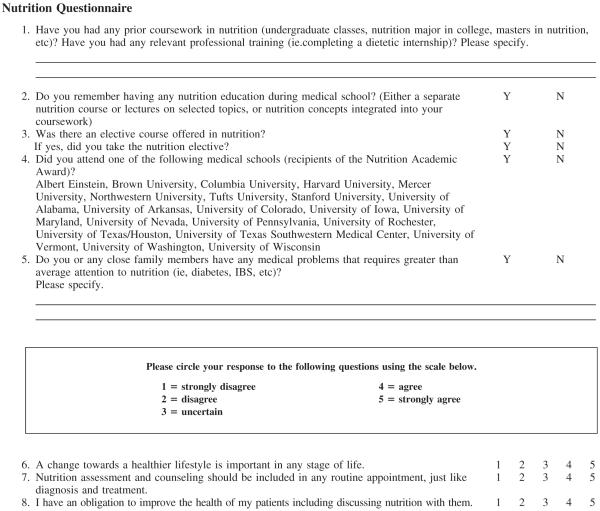

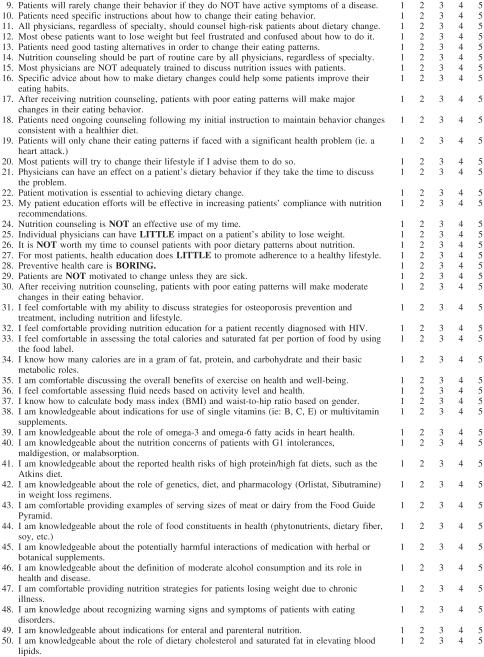

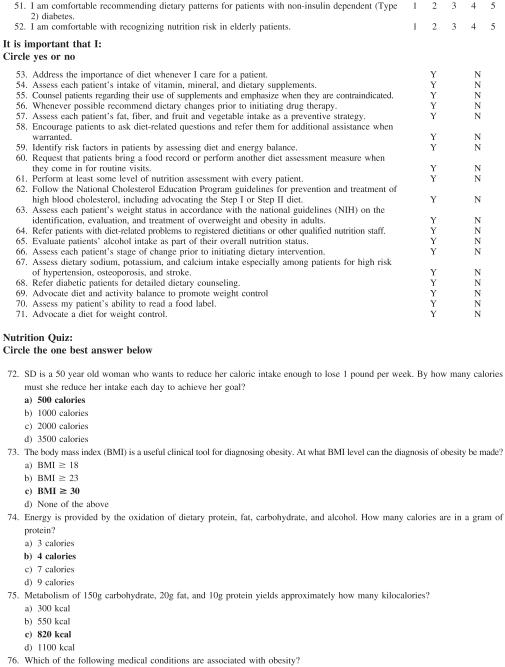

The survey instrument was a 111-item close-ended questionnaire (see online Appendix at www.jacn.org). Nutritional attitudes were assessed using the previously validated Nutrition In Patient care Survey (NIPS) [14]. A validated survey developed by Mihalynuk [15] was used to evaluate self-perceived proficiency in nutrition. Possible responses ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” on a five-point Likert scale. Previous factor analysis by the above authors identified ten attitudinal and self-perceived proficiency subscales, including 1) nutrition in routine patient care, 2) clinical behavior, 3) physician-patient relationship, 4) patient behavior/motivation, 5) physician efficacy, 6) nutrition and prevention/wellness, 7) macronutrients and health, 8) women, infants and children, 9) micronutrients in health, and 10) nutrition and disease management. As no previously validated nutrition knowledge tests have been developed, questions selected from a standardized nutrition textbook were used on the basis of face validity [16]. Nutrition knowledge was assessed by calculating the percentage of correct responses to 40 multiple-choice questions.

Current interns were asked to complete the survey during a seminar at the end of their first year of residency, while incoming interns completed the survey during orientation. Administration occurred in June 2005. The survey was anonymous and all data was de-identified. The study was approved by the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects Research.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System software (version 9.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Missing data were excluded and all data entries were double-checked for errors. The χ2 test was used to assess differences in baseline categorical characteristics between incoming and current interns. The 2-sample t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test was carried out to compare mean attitudes, self-perceived proficiency, and knowledge scores among different training years and prior exposure to nutrition education. We also computed Pearson’s correlation coefficient to assess the association of interns’ attitudes, self-perceived proficiencies, and knowledge. All statistics were performed using a 2-sided test and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 64 incoming interns and 50 current interns, 61 (54%) completed the survey. The characteristics of the sample are provided in Table 1. Because no differences in responses (to attitudinal, self-perceived proficiency, and knowledge questions) were found by training level, all surveyed variables are reported for the group overall. Sixty-two percent of interns had prior nutrition exposure, defined as either having completed undergraduate or graduate coursework in nutrition, reported nutrition education in medical school, or attended a Nutrition Academic Award medical school (16%). Although most medical schools offered a nutrition elective, only 3% of our subjects participated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents

| Personal Characteristics | Current Interns (n = 37) | Incoming Interns (n = 24) | Combined Data (n = 61) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior coursework in nutrition (undergraduate classes, nutrition major in college, masters in nutrition) | 7 (19%) | 2 (8%) | 9 (15%) |

| Nutrition education in medical school* | 19 (51%) | 19 (79%) | 38 (62%) |

| Nutrition elective offered at your medical school? | 10 (27%) | 9 (38%) | 19 (31%) |

| • If yes, did you take it? | 1 (3%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (3%) |

| Attended Nutrition Academic Award medical school? | 4 (11%) | 6 (25%) | 10 (16%) |

| Personal health problems related to nutrition (diabetes, IBS, etc) | 15 (41%) | 9 (38%) | 24 (39%) |

Denotes p < 0.05 (calculated using the χ2 test).

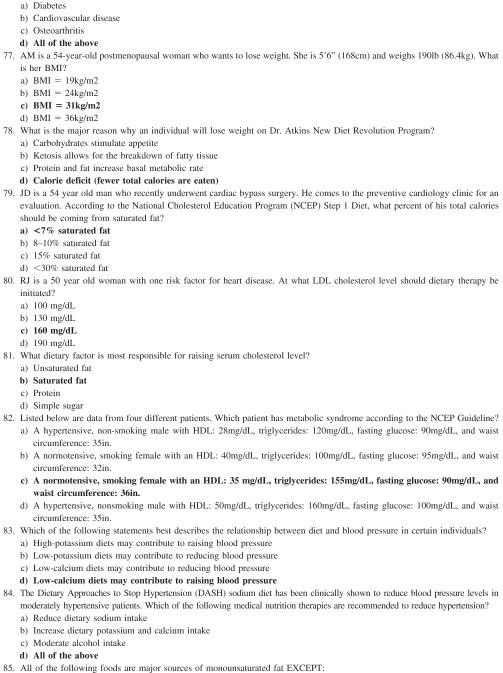

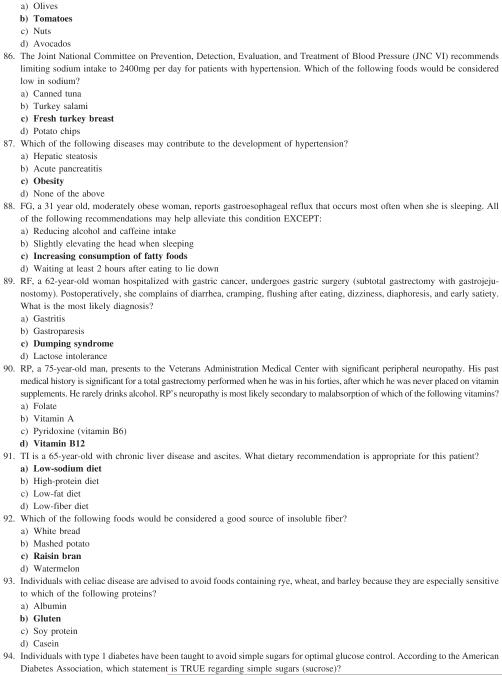

Nutrition Knowledge Test

The average correct score on the knowledge quiz was 66%. Mean knowledge scores for individual topics are provided in Table 2. Knowledge was particularly lacking in the areas of nutrition assessment and obesity, endocrine disease, and cardiovascular nutrition. For example, only half (54%) knew the correct answer to the question “How many calories are in a gram of protein?”

Table 2.

Mean Knowledge Scores for Each Topic*

| Nutrition Knowledge Topic | Mean % Correct n = 61 |

|---|---|

| Nutrition Assessment/Obesity (9 items) | 62% |

| Endocrine Disease (6 items) | 64% |

| Cardiovascular Disease (9 items) | 58% |

| Gastrointestinal Disease (6 items) | 83% |

| Renal Disease (7 items) | 58% |

| Pulmonary Disease (3 items) | 87% |

| All Topics (40 items) | 66% |

Nutritional Attitudes and Self-Perceived Proficiency

Seventy-seven percent of interns agreed or strongly agreed that nutrition assessment should be included in routine primary care visits and 94% agreed or strongly agreed that it was their obligation to discuss nutrition with patients. Most (92%) agreed or strongly agreed that specific advice about how to make dietary changes could help some patients improve their eating habits. However, 86% agreed or strongly agreed that most physicians are not trained to discuss nutritional issues with patients.

Despite having positive attitudes about nutritional assessment and counseling, interns did not feel proficient in their ability to provide adequate counseling. Even when stratified by prior nutrition education, no significant differences were noted between groups. Most respondents felt particularly inadequate in their ability to counsel patients on serving sizes and food labels, vitamin/mineral supplementation, and HIV nutrition. Only 35% of interns agreed or strongly agreed that they felt knowledgeable about the role of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in heart health. Less than half (46%) of respondents felt comfortable calculating BMI and waist-to-hip ratio. Slightly more (58%) interns felt knowledgeable about the role of dietary cholesterol and saturated fat in elevating blood lipids. In contrast, 89% of respondents expressed proficiency in discussing the benefits of exercise with patients.

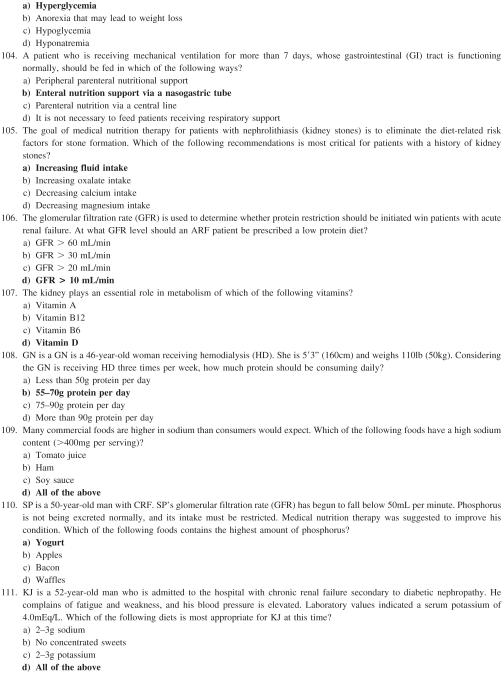

Associations between Measures

There was no correlation among knowledge, attitudes, and self-perceived proficiency in nutrition. Prior training in nutrition was not associated with a difference in knowledge or attitude items. However, interns who had prior exposure to nutrition education reported more negative attitudes overall about physician self-efficacy (p = 0.03). In particular, interns with prior nutrition education were more negative about the utility of counseling on increasing patients’ compliance with nutritional recommendations. Questions relating to physician efficacy are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Physician Efficacy Items

| Question | Interns WITH Prior Nutrition Exposure | Interns WITHOUT Prior Nutrition Exposure | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Agree | % Agree | ||

| Most patients will try to change their lifestyle if I advise them to do so | 19% | 26% | 0.51 |

| Physicians can have an effect on a patient’s dietary behavior if they take the time to discuss the problem. | 78% | 87% | 0.40 |

| For most patients, health education does little to promote adherence to a healthy lifestyle.† | 62% | 65% | 0.81 |

| After receiving nutrition counseling, patient with poor habits will make major changes in their eating behavior. | 16% | 35% | 0.09 |

| My patient-education efforts will be effective in increasing patients’ compliance with nutritional recommendations. | 58% | 87% | 0.02 |

| After receiving nutritional counseling, patients with poor eating habits will make moderate changes in their eating behavior. | 49% | 70% | 0.11 |

| Average percent agree for entire physician efficacy subscale | 48% | 62% | 0.03 |

Response scale to each item: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = uncertain, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree.

Reverse scored, 5 = 1, 4 = 2, 2 = 4, 1 = 5.

“Percent agree” was calculated by adding the number of respondents who answered 4 or 5.

P values were calculated using the χ2 test.

DISCUSSION

We used previously validated questionnaires and a multiplechoice quiz to examine the attitudes, self-perceived proficiency, and nutrition knowledge of internal medicine interns. Consistent with prior studies [11,12,17], interns answered only 66% of knowledge questions correctly overall. They performed best on general nutrition knowledge and worse on specific nutrition interventions. There were notable deficits in knowledge of nutrition assessment and obesity, endocrine nutrition, and cardiovascular nutrition.

Self-perceived proficiency was also low; fewer than one-third of participants were confident in their ability to assess the nutritional status of patients or to discuss general nutritional issues. However, they did feel proficient in more general lifestyle topics, such as counseling patients on the benefits of exercise and the impact of alcohol consumption on health and disease. Similar findings were reported by Mihalnyuk [15]. Proficiency scores were significantly lower for specific topics as opposed to general nutrition. For example, only 46% of interns felt proficient in calculating BMI and waist-hip ratios and 33% were confident in their ability to analyze food labels.

We found that prior nutrition education was associated with more negative attitudes about the utility of nutrition interventions among residents who are likely several years removed from their nutrition coursework, given that nutrition is typically integrated into the pre-clinical curriculum of medical education [18]. Similarly negative views about physician efficacy were reported in a study by Tobin et al., in which the Nutrition In Patient care Survey (NIPS) was administered to all medical students at Mercer University School as a baseline measure prior to the development of a horizontal and vertical nutrition curriculum. Prior exposure to nutrition was presumably minimal [19]. And while multiple studies of the immediate impact of nutrition interventions among medical students found improvements in knowledge, confidence, and self efficacy [20,21], our work, similar to others [22], suggests there may be a deterioration of these gains and raises questions about the optimal timing of nutrition education and its’ integration into the medical education curriculum.

Medical students may not grasp the clinical relevance of nutrition when it is placed within the preclinical years. As an alternative, nutrition education has been incorporated into all four years of medical education at a number of institutions [23,24]. Preliminary evaluation of this approach suggests that students became knowledgeable about nutrition and were better able to address the nutritional needs of their patients than their counterparts in a traditional curriculum [24]. Further study is needed to determine whether restructuring nutrition education will be associated with a more positive attitude toward its clinical utility.

We suggest that resident physicians’ knowledge and counseling skills can be enhanced by a shift in the timing of nutrition education, with an emphasis during the clinical clerk-ships in medical school and throughout postgraduate training. Given the trend towards office-based nutrition intervention [25], the ambulatory care rotation may be a particularly opportune time to integrate nutrition into curricula. Medical students and residents have significantly more contact with patients during these times, maximizing opportunities to practice and further develop nutrition skills. In an effort to standardize nutrition education for residency programs, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s Group on Nutrition (GON) created The Physicians’ Curriculum in Clinical Nutrition [26]. This monograph, most recently updated in 2005, emphasizes the integration of nutrition education into patient care activities in both the inpatient and outpatient settings and provides specific strategies for incorporating nutrition education into residency curricula. Core educational guidelines applicable to primary care providers are also included.

Several studies have shown that the presence of a physician nutrition specialist (PNS) is another important factor for effective nutrition training for physicians [27-29]. Lazarus et al. studied the impact of a nutrition education program provided by a physician nutrition specialist in a family practice residency program and found significant increases in the nutrition knowledge of resident physicians. Patients were also found to be more knowledgeable and more compliant with nutrition recommendations [30,31]. Kirby similarly found improvements in nutrition knowledge after an intervention by a physician nutrition specialist in a family practice residency program [32]. Given these findings, a 1995 report by the American Society for Clinical Nutrition recommended that each major medical center employ a full time faculty member with expertise in nutrition who can serve as a role model in incorporating nutrition into patient can and can advocate for change in medical school and residency curricula [33]. Further study is needed to identify effective methods of incorporating nutrition into the medical curriculum.

Our study has several limitations. Our results may not be generalizible to other populations of interns or residents, as all participants in our study were internal medicine interns at a single institution, the majority of whom were from medical schools within the New York metropolitan area, and few had attended schools that were recipients of the Nutrition Academic Award. Just over half of the eligible study population completed our questionnaire, perhaps introducing selection bias. Most of the non-responders were from the incoming intern class, to whom surveys were handed out during their busy orientation. Many of the interns may not have had time or may have felt too overwhelmed to complete the questionnaire. However, because completion of the survey was voluntary, we believe that those interns with more positive attitudes and experiences in nutrition completed the questionnaire, thereby making our estimates conservative with regard to lack of confidence and knowledge toward clinical nutrition. The knowledge quiz came from a standard nutrition textbook but was not validated, and test fatigue due to the length of the questionnaire may have led to lower overall scores. Finally, we cannot determine whether the differences in attitudes, self-perceived proficiency, and knowledge were correlated with self-reported differences in clinical practice.

Despite these drawbacks, our survey corroborated previous findings of significant deficits in medical nutrition education, with low scores in knowledge and self-perceived proficiency regardless of prior coursework (and perhaps because of it), providing a guide for curriculum development. As our study shows, our current system of nutrition education falls short of its goals, and education efforts must address not only knowledge gaps and effective clinical skills, but perhaps more importantly must create a reason for residents to remain optimistic and empowered regarding the utility of addressing their patients’ nutritional issues in practice. Further study is needed to determine how to best accomplish this as we face our rising epidemic of poor nutrition and obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Christopher Vinnard, MD, MPH for his editorial work and Mr. Nishu Sood, BS, MBA for his contributions to database development.

There is no financial support or author involvement with organization(s) with financial interest in the subject matter. Dr. Herring is supported by an institutional national research service award #5 T32HP1101-19.

APPENDIX

Footnotes

Paper presented in poster form, entitled “Teaching Residents about Nutrition and Obesity: A Needs Assessment,” at the 2006 Society for General Internal Medicine Mid-Atlantic Regional Meeting in Hershey, PA and the 2006 Society for General Internal Medicine National Meeting in Los Angeles, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pi-Sunyer X. Medical hazards of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:657–660. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KF, Graubard BI, Willamson DF, Gail MH. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293:1861–1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushner R. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24:546–552. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galuska D, Will J, Serdula M, Ford E. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA. 1999;282:1576–1578. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glanz K. Review of nutritional attitudes and counseling practices of primary care physicians. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(Suppl):2106S–2119S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.6.2016S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson T, Stone E, Grundy S, McBride P, Van Horn L, Tobin BW, the NAA Collaborative Group Translation of nutritional sciences into medical education: the Nutrition Academic Award Program. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:164–170. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of American Medical Colleges [Accessed September 2006];Annual graduating medical student survey. Available at: www.aamc.org/meded/gfq/qu00.all.pdf.

- 9.Deen D, Spencer E, Kolasa K. Nutrition education in family practice residency programs. Family Med. 2003;35:105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn RF. Continuing medical education in nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(Suppl):981S–984S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.981S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu SP, Wu MY, Liu JF. Nutrition knowledge, attitude, and practice among primary care physicians in Taiwan. J Am Coll Nutr. 1997;16:439–442. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1997.10718711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause TO, Fox HM. Nutritional knowledge and attitudes of physicians. J Am Diet Assoc. 1977;70:607–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Block JP, DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP. Are physicians equipped to address the obesity epidemic? Knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. Prev Med. 2003;36:669–675. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGaghie WC, Van Horn L, Fitzgibbon M, Telser A, Thompson JA, Kushner RF, Prystowsky JB. Development of a measure of attitude towards nutrition in patient care. A J Prev Med. 2001;20:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mihalynuk TV, Scott CS, Coombs J. Self-reported nutrition proficiency is positively correlated with perceived quality of nutrition training of family physicians in Washington State. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1330–1336. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hark L, Morrison G. Review questions. In: Hark L, Morrison, editors. Medical Nutrition and Disease: A Case-Based Approach. 3rd ed. Blackwell Publishing; Malden, MA: 2003. pp. A7–A42. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temple NJ. Survey of nutrition knowledge of Canadian physicians. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999;18:26–29. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams KM, Lindell KC, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH. Status of nutrition education in medical schools. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(Suppl):941S–944S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.941S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobin B, Welch K, Dent M, Smith C, Hooks B, Hash R. Longitudinal and horizontal integration of nutrition science into medical school curricula. J Nutr. 2003;133:567S–572S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.2.567S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conroy MB, Delichatsios HK, Hafler JP, Rigotti NA. Impact of preventive medicine and nutrition curriculum for medical students. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson JB, Gillham MB, Kirk LM, Reddy ST, Battles JB. Enhancing self-efficacy and patient care with cardiovascular nutrition education. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:296–302. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinsier RL, Boker JR, Morgan SL, Feldman EB, Moinuddin JF, Mamel JJ, DiGirolamo M, Borum PR, Read MS, Brooks CM. Cross-sectional study of nutrition knowledge and attitudes of medical students at three points in their medical training at 11 southeastern medical schools. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:1–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taren DL, Thomson CA, Koff NA, Gordon PR, Marian MJ, Bassford TL, Fulginiti JV, Ritenbaugh CK. Effect of an integrated nutrition curriculum on medical education, student clinical performance, and student perception of medical-nutrition training. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krebs NF, Primak LE. Comprehensive integration of nutrition into medical training. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(Suppl):945S–950S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.945S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eaton C, McBride P, Gans K, Underbakke G. Teaching nutrition skills to primary care providers. J Nutr. 2003;133:563S–566S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.2.563S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deen D, Kolasa K, editors. Physicians’ Curriculum in Clinical Nutrition. Society for Teachers of Family Medicine, 2001. 2005 June; updated. http:/www.stfm.org/pdfs/GroupOnNutrition.pdf.

- 27.Boker J, Weinsier R, Brooks C, Olson A. Components of effective clinica-nutrition training: a national survey of graduate medical education (residency) programs. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:568–571. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinsier RL. Medical-nutrition education-factors important for developing a successful program. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:837–840. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinsier RL, Boker JR, Brooks C, et al. Nutrition training in graduate medical (residency) education: a survey of selected training programs. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:957–962. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazarus K, Weinsier RL, Boker Nutrition knowledge and practices of physicians in a family-practice residency program: the effect of an education program provided by a physician nutrition specialist. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:319–325. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazarus K. Nutrition practices of family physicians after education by a physician nutrition specialist. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(Suppl):2007S–2009S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.6.2007S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirby R, Chauncey K, Jones B. The effectiveness of a nutrition education program for family practice residents conducted by a family practice resident-dietitian. Family Med. 1995;73:246–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halstead C. Clinical nutrition education-relevance and role models. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:192–196. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]