Abstract

Cell proliferation requires the coordinated activity of cytosolic and mitochondrial metabolic pathways to provide ATP and building blocks for DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis. Many metabolic pathway genes are targets of the c-myc oncogene and cell cycle regulator. However, the contribution of c-Myc to the activation of cytosolic and mitochondrial metabolic networks during cell cycle entry is unknown. Here, we report the metabolic fates of [U-13C] glucose in serum-stimulated myc−/− and myc+/+ fibroblasts by 13C isotopomer NMR analysis. We demonstrate that endogenous c-myc increased 13C-labeling of ribose sugars, purines, and amino acids, indicating partitioning of glucose carbons into C1/folate and pentose phosphate pathways, and increased tricarboxylic acid cycle turnover at the expense of anaplerotic flux. Myc expression also increased global O-linked GlcNAc protein modification, and inhibition of hexosamine biosynthesis selectively reduced growth of Myc-expressing cells, suggesting its importance in Myc-induced proliferation. These data reveal a central organizing role for the Myc oncogene in the metabolism of cycling cells. The pervasive deregulation of this oncogene in human cancers may be explained by its role in directing metabolic networks required for cell proliferation.

Introduction

Cell proliferation is an essential component of normal growth and development, and as such, is highly regulated by hormonal and environmental factors. While our knowledge of cell cycle regulatory genes is advanced, the links between the cell cycle machinery and supply of metabolic intermediates required for cell division is less well understood. Of the known transcription factors exerting cell cycle control, a likely candidate for this regulatory role is the c-myc oncogene, due to the diversity of known target genes involved in both cell cycle and metabolic pathways (Zeller et al., 2006). Induction of Myc occurs rapidly in response to growth factors stimulating cell cycle entry, with mRNA levels increasing 20 fold within the first 2 h after serum addition (Dean et al., 1986). Global analysis of downstream targets reveals that Myc potentially regulates up to 15% of human genes through direct binding to target gene sequences (Zeller et al., 2006), and may have even broader effects on gene expression through global chromatin remodeling (Knoepfler et al., 2006).

Notably, Myc regulates key genes in glycolysis, C1/folate, purine, pyrimidine and lipid metabolism (Dang et al., 2006; Zeller et al., 2006). In addition, Myc targets genes required for mitochondrial DNA replication and transcription (Li et al., 2005). Hence, Myc supports the bi-genomic transcriptional regulation necessary for mitochondrial biogenesis, a key event during cell cycle entry (Mandal et al., 2005; Morrish et al., 2008). In summary, the network of known Myc gene targets suggests that Myc is involved in orchestrating the changes in cell metabolism necessary for cell cycle entry. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies of central carbon metabolic flux or carbon partitioning associated with physiologic Myc expression. Our goal in this study was to address this question.

Results and Discussion

Myc increases oxidative metabolism of glucose during cell cycle entry

Rat1A fibroblasts with myc−/− and myc+/+ genotypes were incubated with [U-13C] labeled glucose starting at 12 h after serum addition to quiescent cells. The metabolic fates of 13C atoms can be assessed in a wide range of metabolites based on the resonant absorption signals of 13C nuclei when placed in an external magnetic field. The positions of 13C tracer in the carbon backbone of metabolites vary according to the proportional fluxes of alternate metabolic pathways, which can be derived by measurements of the relative abundance of the different labeling patterns. NMR spectroscopy was performed on cell extracts after 4 h of labeling to approximate steady state for analysis of 13C-labeled metabolites. This allowed us to compare the metabolic profiles during the G0 to S phase transition of myc+/+ cells, which enter S phase at 16 h, and myc−/− cells, which have delayed S phase entry (Schorl and Sedivy, 2003; Tollefsbol et al., 1990).

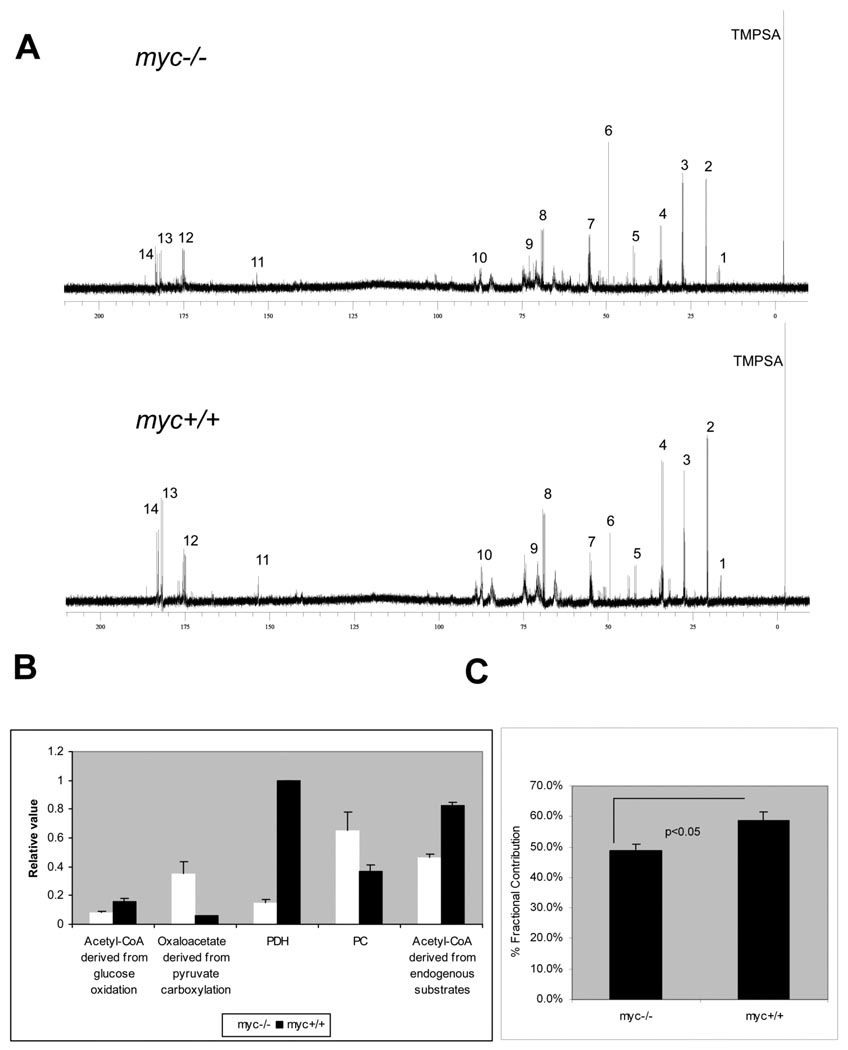

Fig. 1A shows representative 1H-decoupled, 13C NMR spectra from cell extracts. 13C-incorporation was observed for multiple metabolites, with the most prominent peaks corresponding to glutamate and lactate resonance signals. Inspection of the glutamate spectra indicated higher levels of 13C-labeled glutamate and glutamine in myc+/+ compared to myc−/− cells (Supplemental Fig. S1). This was confirmed by quantitative mass isotopomer analysis using LC/MS/MS. We detected a 20% increase in the fractional contribution of 13C-labeled glutamate to the total glutamate pool in myc+/+ cells, compared to myc−/− cells (Fig. 1C). Glutamate is in equilibrium with alpha-ketoglutarate and can be used to assess TCA cycle flux using the program tcaCALC (Malloy et al., 1990). In our experiments, the multiplet resonances of glutamate were well resolved (Supplemental Fig. S1), and the areas of the glutamate C2, C3 and C4 resonances were used to calculate relative flux of glucose carbons into the TCA cycle via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and pyruvate carboxylase (PC). Results of this analysis, illustrated in Fig. 1B, demonstrate a ~7 fold greater PDH flux in myc+/+ cells compared to myc−/− cells. We also evaluated the contributions of [U-13C] glucose and endogenous substrates to acetyl CoA entering the TCA cycle (Fig 1B). Analysis by tcaCALC indicated that both [U-13C] pyruvate and endogenous unlabelled substrates each supplied approximately twice as much acetyl CoA in myc+/+ cells compared to myc−/− cells.

Figure 1. 13C NMR analysis of 13C glucose metabolism in myc−/− and myc+/+ cells during cell cycle entry.

(A) 1H decoupled 13C spectra. Key. (1) C3 alanine, (2) C3 lactate, (3) C3 glutamate, (4) C4 glutamate, (5) C2 glycine, (6) C5 proline, (7) C2 glutamate, (8) C2 lactate, (9) ribose and sugar moieties, (10) C4‘ NXP, (11) C2 Adenine, (12) C1 glutamate, (13) C5 glutamate, (14) C1 lactate. TMPSA is internal standard. NXP refers to the mono- di- or triphosphate form of any nucleotide. (B) tcaCALC-derived relative fluxes. (C) Percentage contribution of 13C labeled glutamate to total glutamate by LC/MS/MS mass isotopomer analysis.

In contrast, there is higher relative metabolism of pyruvate by the anaplerotic enzyme PC for the myc−/− cells, resulting in a substantially higher PC/PDH flux ratio (4.3 compared to 0.37 for myc+/+ cells). In keeping with their higher relative PC flux, myc−/− cells had a 6-fold greater contribution of 13C pyruvate to the total oxaloacetate pool via pyruvate carboxylation. These results identify significant qualitative differences between myc+/+ and myc−/− cells in substrate partitioning and pathway flux into the TCA cycle during preparation for S phase entry, consistent with observed differences in serum-induced changes in mitochondrial mass and respiration (Morrish et al., 2008).

The Myc-dependent alterations in TCA cycle and related fluxes can be explained by changes in Myc-regulated gene expression. Induction of Myc (MycER) in myc−/− cells results in temporal repression of PDK2 and PDK4 (Morrish et al., 2008), which would lead to increased pyruvate oxidation by decreasing inhibitory phosphorylation of PDH. Expression of PC is also temporally decreased by Myc induction, reinforcing the allocation of pyruvate to supply the mitochondrial acetyl-CoA pool. These results, together with the effects of Myc on mitochondrial bioenergetics during cell cycle entry, point to a key role for Myc in augmenting mitochondrial capacity and directing substrates to mitochondria during the transition from maintenance energy requirements of quiescent cells to the active biosynthesis of cycling cells (Morrish et al., 2008).

Myc increases glucose carbon flux into branch metabolic pathways of glycolysis

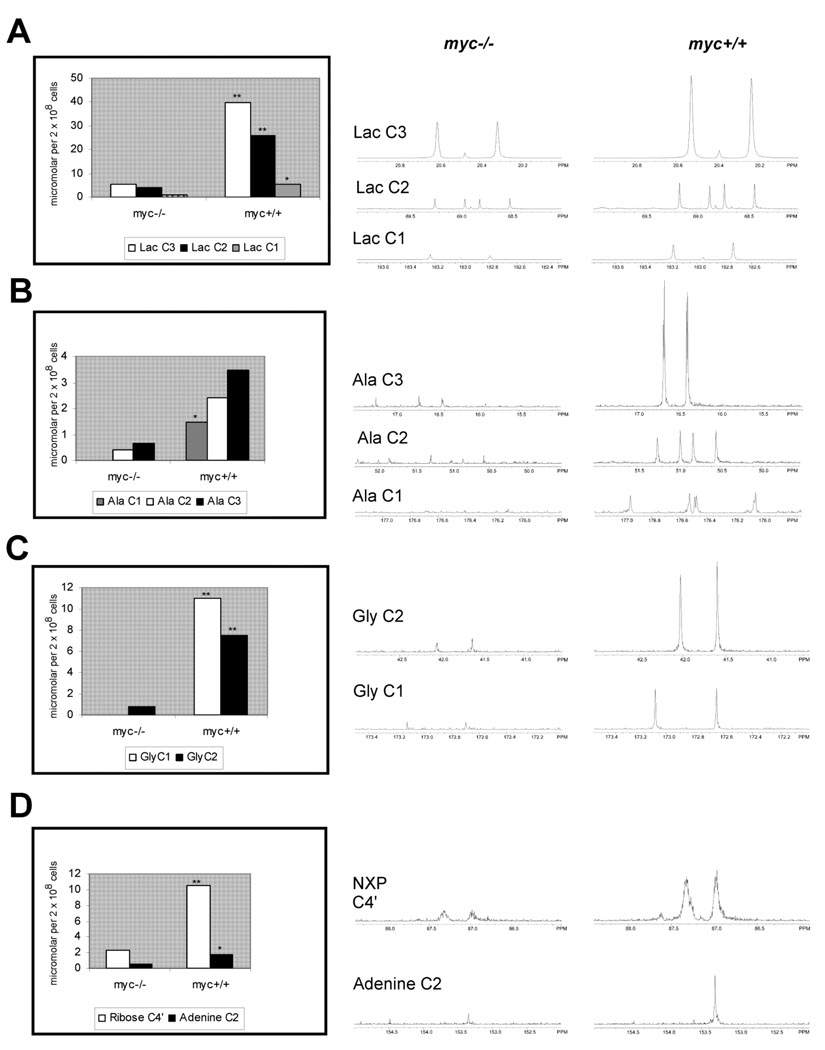

Metabolism of glucose supplies intermediates for amino acid synthesis, C1/folate metabolism, and pentose phosphate and hexosamine biosynthetic pathways, in addition to lactate generation. We found evidence for increased glycolytic flux as 13C-labeling of lactate was greater in myc+/+ cells compared to myc−/− cells (Fig. 2A). This result was expected, as multiple glycolytic genes are targets of Myc (Osthus et al. 2000), and we have previously shown increased conversion of glucose to pyruvate and lactate in Rat1A myc+/+ cells compared to myc−/− cells (Morrish et al. 2008). When we evaluated the spectra for additional 13C-enriched intermediary metabolites, we found increased levels of 13C-labeled alanine and glycine, derived from pyruvate and the glycolytic intermediate 3-phosphoglycerate, respectively (Fig. 2B,C). Glycine is a precursor for de novo purine synthesis as well as a carbon donor for C1/folate metabolism required for nucleotide biosynthesis. We observed 13C labeling of the C2 position in the adenine base, originating from N10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate, as well as increased incorporation of 13C into the ribose moiety of nucleotides, demonstrated by a 3-fold increase in ribose C4’ labeling (Fig 2D). Folate is required for one-carbon transfer reactions in purine and thymidylate biosynthesis, as well as epigenetic modification of DNA and proteins. Expression of ~50% of genes involved in folate metabolism are increased following Myc induction (Morrish et al. 2008), and SHMT2 is one of only two Myc target genes results shown to complement growth defects in myc−/− cells (Nikiforov et al., 2002). Treatment with the dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, methotrexate, inhibited growth of myc+/+ cells more effectively than myc−/− cells (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained using myc−/− cells transfected with inducible Myc (myc−/− MycER) (Fig. 3C). These results provide additional evidence of the close relationship between nucleotide synthesis and Myc-dependent cell proliferation (Mannava et al., 2008), and establish direct links between increased glucose metabolism and nucleotide synthesis in Myc-expressing cells.

Figure 2. 13C labeling of selected metabolites in myc−/− and myc+/+ cells.

13C enrichment at individual carbons (left). Data is calculated from integrated peak areas relative to internal standard. Mean of 3 experiments. Significant differences (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.001) assessed by Student’s t test. Corresponding NMR spectra (right) for (A) lactate, (B) alanine, (C) glycine, (D) NXP ribose C4’ and adenine C2.

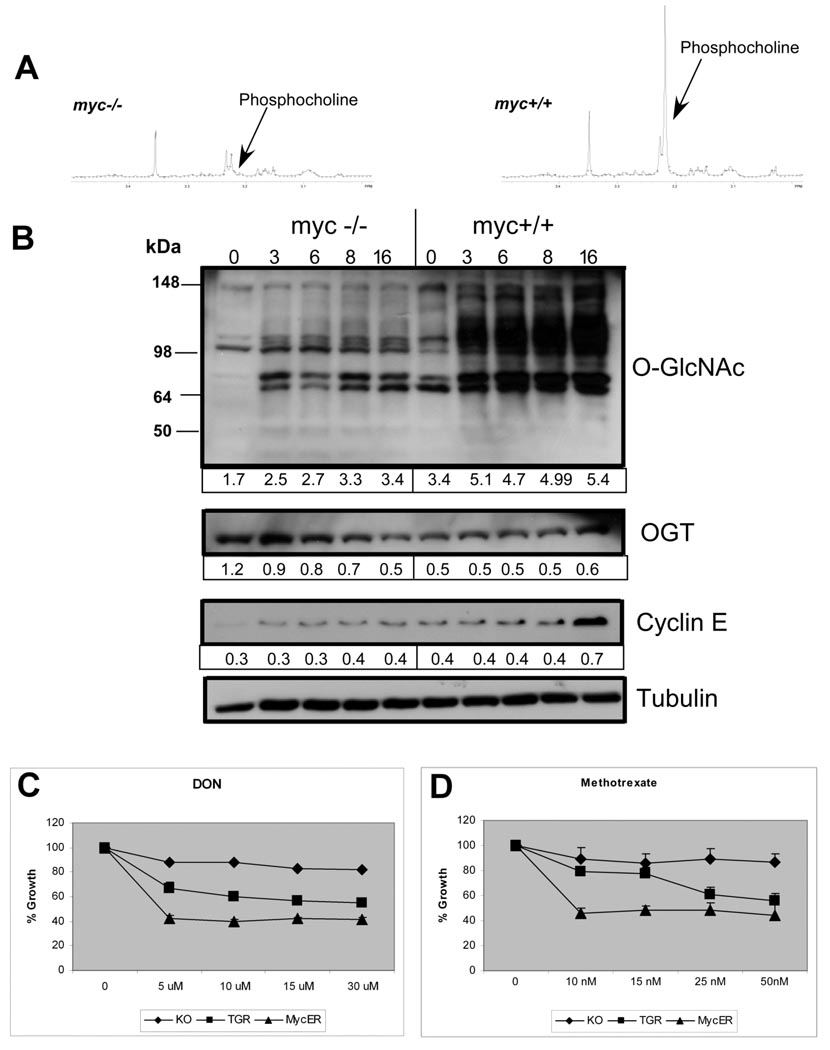

Figure 3. Metabolic pathways required for cell cycle progression in myc+/+ cells.

(A) Proton spectra for phosphocholine (3.2 ppm). (B) Immunoblots showing O-GlcNAcylated proteins and OGT expression with serum stimulation. Cyclin E and tubulin are positive and loading controls. Densitometry values indicated below each lane (ImageQuant). (C) Dose-response assay of cell growth by HO33342 staining for methotrexate and DON. TGR represents myc+/+ cells. Relative growth rates of untreated cell lines: myc−/− 0.69, mycER 0.83. Representative of 3 experiments in triplicate.

Myc increases phosphocholine levels

Phosphocholine is an intermediate in phosphatidylcholine synthesis and is required for membrane biosynthesis during cell cycle entry (Jackowski, 1994). Since phosphocholine is difficult to quantitate in 13C spectra due to spectral overlap, we used 1D-1H spectra to evaluate phosphocholine content. We found a 3-fold increase in phosphocholine levels in serum-stimulated myc+/+ cells compared to myc−/− cells (Fig. 3A). Myc induction increases choline kinase expression (Morrish et al., 2008), and elevated phosphocholine levels are associated in neuroblastomas with N-Myc amplification (Peet et al., 2007). The rate-limiting enzyme in phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) synthesis, CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT/PCYT1A), is also a Myc target gene (Li et al., 2003), suggesting Myc increases glycerophospholipid synthesis. The increased TCA cycle flux observed in myc+/+ cells may also play a role in increased glycerophospholipid synthesis by generating acetyl groups required for de novo fatty acid synthesis. In preliminary results, we observed that fatty acid synthesis from [U-13C] glucose is increased in myc+/+ cells (Morrish, unpublished). These results may be relevant to the delayed cell cycle entry of myc−/− cells, as net accumulation of PtdCho near the G1/S boundary is necessary for membrane synthesis (Jackowski, 1994). PtdCho is also a source of lipid second messengers involved in cell cycle progression (Hunt and Postle, 2004).

O-GlcNAc post-translational modification is regulated by Myc

Glycolytic (fructose-6-phosphate) and TCA cycle intermediates (glutamine, acetyl-CoA) are substrates for the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP). Since the 13C data demonstrated increased glycolytic and TCA cycle flux in serum-stimulated myc+/+ cells, we looked for global differences in serum-induced protein modification by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) in myc+/+ and myc−/− cells. Immunoblotting of cell extracts using an O-GlcNAc-specific antibody detected multiple bands, with an overall temporal increase after serum addition in myc+/+ cells. Several bands were detected at lower intensity in serum-starved cells, while others appeared with serum stimulation (Fig. 3B). The number of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins detected in myc−/− cells was reduced and the serum response significantly attenuated.

Increased O-GlcNAc protein modification may result from increased expression of modifying enzyme, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), and/or increased hexosamine synthesis. OGT protein expression was reduced as demonstrated by immunoblotting in myc+/+ cells compared to myc−/− cells under serum-deprived conditions and an early response to serum was not observed (Fig. 3C). Hence, early Myc-associated increases in protein O-GlcNAcylation are not explained by upregulation of OGT expression.

To examine the role of O-GlcNAcylation in Myc-dependent proliferation, we treated cells with 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON), an inhibitor of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFAT), the first and rate-limiting enzyme of the hexosamine pathway. Both myc+/+ and induced myc−/− MycER cells were more sensitive to growth inhibition at 48 h, suggesting an important role for the HBP during proliferation in myc+/+ cells (Fig. 3D). O-GlcNAc protein modification is a dynamic process analogous to phosphorylation (Hart et al., 2007). Interference with O-GlcNAc modification has been shown to disrupt cell cycle progression (Slawson et al., 2005). Several HBP genomic loci are bound by Myc, including GNS and NAGPA (Li et al., 2003) and HBP genes are enriched in expression profiling of Myc-induced pancreatic neoplasia (Lawlor et al., 2006). In addition to transcriptional regulation of the HBP, Myc may increase the supply of essential substrates for hexosamine biosynthesis as a consequence of the increased glycolytic and TCA cycle fluxes demonstrated by 13C isotopomer analysis.

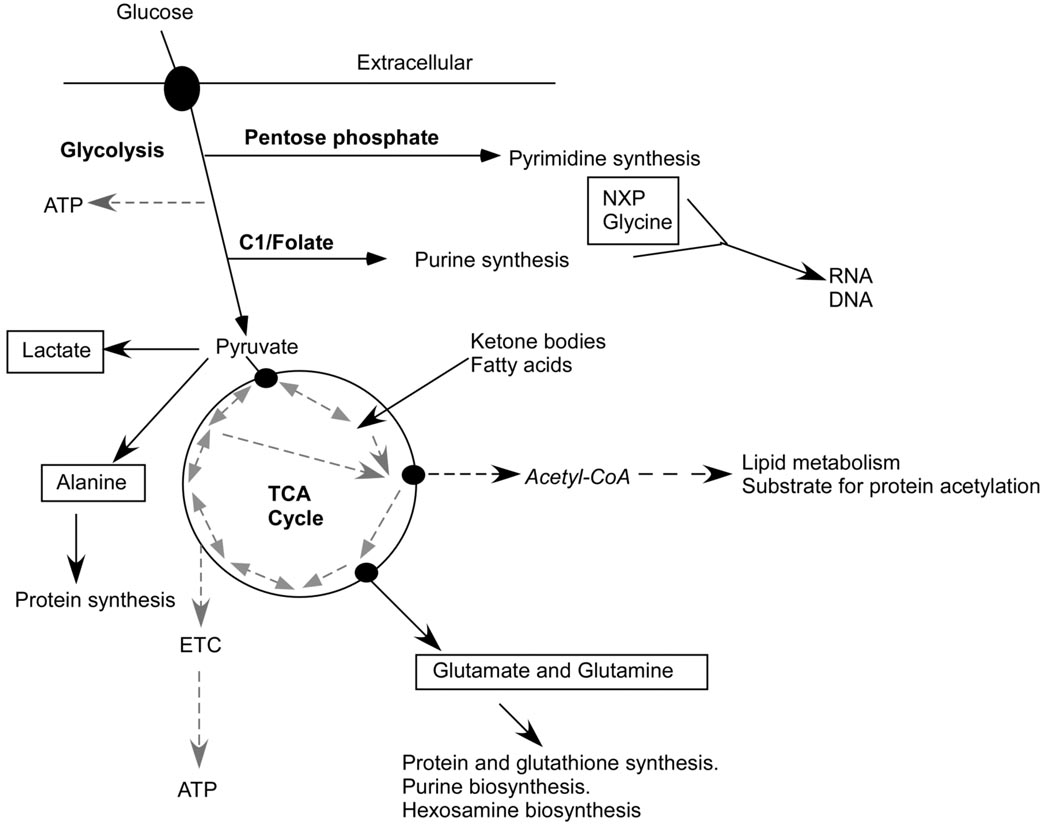

In conclusion, our results demonstrate the broad effects of endogenous Myc expression on glucose carbon flux in both catabolic and anabolic pathways, in response to serum stimulation, including glycolysis, the TCA cycle, the pentose phosphate pathway, and C1/folate metabolism (Fig. 4). The obligate role of mitochondria in C1/folate metabolism raises the possibility that Myc-induced mitochondrial biogenesis provides for biosynthesis of key intermediate metabolites in addition to bioenergetic requirements for cell cycle progression. This extensive programming of metabolism may be unique to Myc. For example, HIF-1 alpha directs increased glycolytic metabolism, but at the expense of anabolic synthesis and mitochondrial respiration (Lum et al., 2007). Finally, the observation of Myc effects on O-GlcNAc post-translational protein modification provides an interesting example of the potential intersection of metabolome and transcriptome networks for signal amplification and integration.

Figure 4.

Myc regulation of glucose metabolism may provide key intermediates, energy and reducing power for cell proliferation. 13C-labeled metabolites from this study are boxed. Dashed arrows link mitochondrial metabolites with reversible (double-ended arrows) or irreversible (single arrows) reactions. Both glycolysis and the mitochondrial TCA cycle generate metabolic intermediates, in addition to ATP, providing building blocks for protein, lipid and nucleic acid synthesis. Post-translational protein modification may be subject to substrate-level control, including extra-mitochondrial acetyl-CoA, derived from intra-mitochondrial pyruvate and fatty acid metabolism, and glucosamine-6-phosphate, derived from fructose-6-phosphate and glutamine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank John Sedivy for cell lines. This work utilized the MMC Database supported by NIH grants R21 DK070297 and P41 RR02301, the MDL database (www.mdl.imb.liu.se), and the Human Metabolome database (www.hmbd.ca). A portion of this research was performed at EMSL, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the Department of Energy's Office of Biological and Environmental Research at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. This work was funded by RO1CA106650-02 (DH). Development of the program tcaCALC (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) was supported by H47669-16, a Dept. of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award to C.R. Malloy, and RR02584.

References

- Dang CV, O'Donnell KA, Zeller KI, Nguyen T, Osthus RC, Li F. The c-Myc target gene network. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Levine RA, Ran W, Kindy MS, Sonenshein GE, Campisi J. Regulation of c-myc transcription and mRNA abundance by serum growth factors and cell contact. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:9161–9166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW, Housley MP, Slawson C. Cycling of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature. 2007;446:1017–1022. doi: 10.1038/nature05815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt AN, Postle AD. Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis inside the nucleus: is it involved in regulating cell proliferation? Adv Enzyme Regul. 2004;44:173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski S. Coordination of membrane phospholipid synthesis with the cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3858–3867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoepfler PS, Zhang XY, Cheng PF, Gafken PR, McMahon SB, Eisenman RN. Myc influences global chromatin structure. EMBO J. 2006;25:2723–2734. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor ER, Soucek L, Brown-Swigart L, Shchors K, Bialucha CU, Evan GI. Reversible kinetic analysis of Myc targets in vivo provides novel insights into Myc-mediated tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4591–4601. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Wang Y, Zeller KI, Potter JJ, Wonsey DR, O'Donnell KA, et al. Myc stimulates nuclearly encoded mitochondrial genes and mitochondrial biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6225–6234. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6225-6234.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Van Calcar S, Qu C, Cavenee WK, Zhang MQ, Ren B. A global transcriptional regulatory role for c-Myc in Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8164–8169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332764100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum JJ, Bui T, Gruber M, Gordan JD, DeBerardinis RJ, Covello KL, et al. The transcription facgtor HIF-1alpha plays a critical role in the growth factor-dependent regulation of both anaerobic and aerobic glycolysis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1037–1049. doi: 10.1101/gad.1529107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FM. Analysis of tricarboxylic acid cycle of the heart using 13C isotope isomers. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H987–H995. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S, Guptan P, Owusu-Ansah E, Banerjee U. Mitochondrial regulation of cell cycle progression during development as revealed by the tenured mutation in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2005;9:843–854. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannava S, Grachtchouk V, Wheeler LJ, Im M, Zhuang D, Slavina EG, et al. Direct role of nucleotide metabolism in C-MYC-dependent proliferation of melanoma cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2392–2400. doi: 10.4161/cc.6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrish FM, Neretti N, Sedivy JM, Hockenbery DM. The oncogene c-Myc coordinates regulation of metabolic networks to enable rapid cell cycle entry. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1054–1066. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.8.5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov MA, Chandriani S, O'Connell B, Petrenko O, Kotenko I, Beavis A, et al. A functional screen for Myc-responsive genes reveals serine hydroxymethyltransferase, a major source of the one-carbon unit for cell metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5793–5800. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5793-5800.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osthus RC, Shim H, Kim S, Li Q, Reddy R, Mukherjee M, et al. Deregulation of glucose transporter 1 and glycolytic gene expression by c-Myc. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21797–21800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet AC, McConville C, Wilson M, Levine BA, Reed M, Dyer SA, et al. 1H MRS identifies specific metabolite profiles associated with MYCN-amplified and non-amplified tumour subtypes of neuroblastoma cell lines. NMR Biomed. 2007;20:692–700. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorl C, Sedivy JM. Loss of protooncogene c-Myc function impedes G1 phase progression both before and after the restriction point. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:823–835. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawson C, Zachara NE, Vosseller K, Cheung WD, Lane MD, Hart GW. Perturbations in O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine protein modification cause severe defects in mitotic progression and cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32944–32956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefsbol TO, Cohen HJ. The protein synthetic surge in response to mitogen triggers high glycolytic enzyme levels in human lymphocytes and occurs prior to DNA synthesis. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1990;44:282–291. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(90)90073-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller KI, Zhao X, Lee CW, Chiu KP, Yao F, Yustein JT, et al. Global mapping of c-Myc binding sites and target gene networks in human B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17834–17839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604129103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.