Abstract

Background

Maternal mortality remains unacceptably high in developing countries despite international advocacy, development targets, and simple, affordable and effective interventions. In recent years, regard for maternal mortality as a human rights issue as well as one that pertains to health, has emerged.

Objective

We study a case of maternal death using a theoretical framework derived from the right to health to examine access to and quality of maternal healthcare. Our objective was to explore the potential of rights-based frameworks to inform public health planning from a human rights perspective.

Design

Information was elicited as part of a verbal autopsy survey investigating maternal deaths in rural settings in Indonesia. The deceased's relatives were interviewed to collect information on medical signs, symptoms and the social, cultural and health systems circumstances surrounding the death.

Results

In this case, a prolonged, severe fever and a complicated series of referrals culminated in the death of a 19-year-old primagravida at 7 months gestation. The cause of death was acute infection. The woman encountered a range of barriers to access; behavioural, socio-cultural, geographic and economic. Several serious health system failures were also apparent. The theoretical framework derived from the right to health identified that none of the essential elements of the right were upheld.

Conclusion

The rights-based approach could identify how and where to improve services. However, there are fundamental and inherent conflicts between the public health tradition (collective and preventative) and the right to health (individualistic and curative). As a result, and in practice, the right to health is likely to be ineffective for public health planning from a human rights perspective. Collective rights such as the right to development may provide a more suitable means to achieve equity and social justice in health planning.

Keywords: human rights, maternal mortality, developing countries, Indonesia

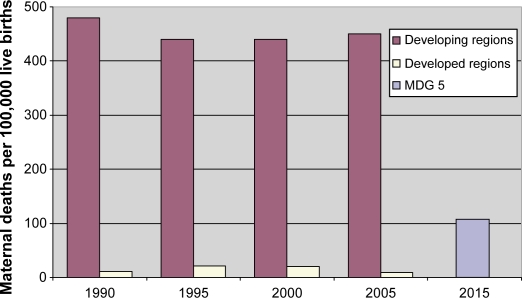

According to the latest estimates, 536,000 maternal deaths occurred worldwide in 2005 (1). Although there are large degrees of uncertainty, two discouraging facts are apparent from the figures. Firstly, 99% of maternal deaths occur in developing countries and secondly, levels of maternal mortality have remained unchanged for almost two decades (Fig. 1) (1–3).

Fig. 1.

Estimates of the maternal mortality ratio 1990–2005 for developed and developing regions and target level required to meet Millennium Development Goal 5. Sources (1–3).

The interventions to treat the life-threatening complications of pregnancy and childbirth are well known: ensuring that deliveries occur in the presence of a skilled health provider who functions with equipment, drugs, supplies and transport (skilled attendance) (4); and access to medical facilities that provide the package of life-saving interventions for the major direct obstetric complications (emergency obstetric care, EmOC) (5). With these interventions it is estimated that over 90% of maternal mortality could be prevented (6).

A target level of maternal mortality was set by the United Nations in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), a series of internationally ratified goals that aim to reduce poverty and improve education and health. The 5th goal aims to improve maternal health with: a 75% reduction in the 1990 levels of maternal mortality by 2015 (Fig. 1) (7, 8) and universal access to reproductive health (9). Given lack of progress to date, concerns exist over the likelihood of achieving the goal (10, 11).

Slow progress may be due, in part, to the complex nature of causality of maternal ill-health. In low income settings, poor maternal health is indicative of pervasive and systemic problems that relate to underlying social issues. These include “lack of education for girls, early marriage, lack of access to contraception, poor nutrition, and women's low social, economic and legal status” (12) which underscores maternal mortality as a social-economic and social-cultural phenomenon, as well as one that pertains to health and healthcare.

In recent years, regard for maternal mortality as a human rights issue has emerged (13–19), primarily by virtue of its preventability (15). Avoidable mortality (and morbidity) as a result of pregnancy and childbirth is connected to a number of human rights. These include the right to non-discrimination, the right to information and education, the right to life survival and development, and the right to the highest attainable standard of health (14).

The right to health was affirmed as part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), in 1948 as follows: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health or himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.” (20). The wording acknowledges that the right to health will not be realised without addressing the underlying determinants of health and without the fulfilment of other human rights such as the right to work, food, shelter, housing, information and education, reflecting the indivisibility and interdependency of human rights.

Certain freedoms and entitlements arise from the right to health. Freedoms include freedom from discrimination, harmful traditional practices and violence (21). Entitlements refer to “a system of health protection” which encompasses “health, goods, services and facilities which are available in adequate numbers, accessible, acceptable and of good medical quality” (22).

Human rights are powerful advocacy tools, which have become prominent in health and development in recent years. In 2002, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights appointed an independent expert, the ‘Special Rapporteur’, to support countries in the application of the right to health (21, 23). In 2005, the Department for International Development (DFID) commissioned a review of rights-based approaches to reducing maternal mortality (24, 25). Most recently, the British government called for frameworks based on the right to health to monitor maternal healthcare in developing countries (26). Policy responses based on rights include: prioritising life-saving interventions; definitions of minimum packages of care and essential medicines; incorporating principles of accountability, participation, dignity, privacy and confidentiality into service delivery; and, the targeted provision of services for the poor and marginalised (23, 27).

In this article, we present a single case of maternal death encountered as part of a verbal autopsy (VA) survey. VA is an established method of assigning a medical cause of death for people who die outside hospitals and health facilities. VA is widely used in developing countries where vital registration systems are missing or inadequate and is used routinely in over 35 sites in Africa and Asia (28–32). The results of VA surveys, quantified cause-specific mortality profiles, are used for surveillance, monitoring and public health planning.

The study was undertaken in Banten Province, Indonesia in January 2008. Indonesia ranks seventh highest in the world for absolute numbers of maternal deaths (19,000 in 2005) (1). Recent estimates of the maternal mortality ratio for Indonesia vary between 307 (33) and 420 (1) maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

The Government of Indonesia (GOI) has made intensive efforts to support the MDGs and to improve maternal health through the expansion and improvement of access to skilled attendance at delivery. The village midwife (Bidan di Desa) programme was launched in 1989 to post a qualified midwife in every non-metropolitan village (34). Village midwives live in and form part of the community, provide a range of integrated maternal and child health services (35) and perform life-saving functions in the event of delivery complications (36). However, despite significant and sustained investment, difficulties of ensuring equitable access to quality care have been empirically demonstrated (37)–(40).

Objective

Our objective was to explore the potential of a rights-based framework to: identify exclusion from access to maternal healthcare services; and foster accountability towards the promotion and protection of women's health during pregnancy and childbirth in public health planning. This was done by applying the circumstances and events in a case of maternal death to a theoretical framework derived from the right to health.

Design

Overall design

The case study method was adopted for the purposes of reporting and analysing information from a single case (41–43). The method is a “distinctive form of empirical enquiry” (42), appropriate when complex relationships exist between context and phenomenon under investigation. The contextual conditions in this case (the individual, behavioural, socio-cultural and health systems processes) are highly relevant and influential to the phenomenon (accessibility and quality of maternal healthcare), making the case study method appropriate for our purposes.

Data collection

Traditionally, VAs are structured interviews with family member(s) on medical signs and symptoms of the deceased. Interview data are then interpreted to conclude a medical cause of death. In the interview, in addition to information on medical signs and symptoms, we collected supplementary information on non-medical circumstances and events that surrounded the death. These data were collected in order to obtain information on avoidable and remediable factors, reflecting the social, cultural and health systems contexts, which may have had a causal link with mortality.

The interview contained two elements. Firstly, a structured series of 75 closed questions on medical signs and symptoms. Secondly, to examine non-medical circumstances and events, we posed open-ended questions in a semi-structured format, with free dialogue. In terms of the latter, we asked respondents: who made the decision to seek care in the emergency; whether there were problems getting to health facilities; whether there were problems when care had been accessed; their opinions on the events; whether they thought the situations could have been improved and how; and whether they felt that the death was preventable. The full interview guide is available from the authors.

The interview was conducted with the deceased's mother and sister. It was conducted by an interviewer recruited for the purposes of the study who had general medical and public health training. The authors also participated in the overall series of interviews, SNQ being present at this particular interview.

The interview was approximately 90 min long. Salient points were recorded on paper. The interview was also audio-recorded for transcription, translation and general reference. Informed consent was obtained from both respondents. We informed the respondents of the purpose of the research, that information given would be treated in confidence and that participating would pose no risk to health services available to them. Since the interview was concerned with events that were potentially painful or distressing to recall, the respondents were able to skip questions or stop the interview at any time if they found it to be upsetting or difficult, or for any other reason.

Analytical approach

Three analytical steps were taken: firstly, a descriptive account of the case is provided with a chronological description of medical signs, symptoms, circumstances and events with supporting quotes from the interview. Secondly, the barriers to access of healthcare services are characterised and categorised to test the proposition that the case illustrates exclusion from access to services. Thirdly, the details of the case are applied to the theoretical framework derived from the right to health to determine whether the right was upheld. The framework is set out in a General Comment, published in 2000 by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). This substantive document sets out four inter-related and essential criteria to assess whether health services and programmes promote and protect the right to health as follows: “health services, goods and facilities … shall be available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality” (22).

Results

Bearing witness: The story of Ibu Rahmi*

Ibu Rahmi was a 19-year-old Indonesian primagravida, who lived in a rural village. She had been educated to junior high school level but did not work. Ibu Rahmi's husband was a public transport driver, to whom she had a forced marriage at age 16. The couple lived with her parents and the family could be classed as poor (they had no toilet in the house; their water-source was an open well; and they had no television, radio or car).

During a seemingly normal pregnancy, in which antenatal care was sought routinely, at approximately 7 months gestation, Ibu Rahmi developed a sudden and severe fever. After several days, the family sought medical advice from the village midwife. The midwife examined Ibu Rahmi and referred her to a military hospital (hospital A), approximately 20 km, or a 1-hour journey, from the village. The woman travelled to the hospital in a rented car, accompanied by family members. On arrival at the facility, Ibu Rahmi was admitted, given fluids, unspecified drugs and bed-rest. After 3 days, Ibu Rahmi discharged herself and returned home to her village. She had not recovered but wanted to avoid further costs of hospital care.

Some days later, the symptoms of severe fever recurred and Ibu Rahmi was taken back to the village midwife. The midwife referred Ibu Rahmi to a second hospital (hospital B), again about 20 km away. The woman and her family travelled to this hospital in rented transport. At the hospital, Rahmi was admitted, given fluids and unspecified drugs. Ibu Rahmi was hospitalised for 2 days but discharged herself again because (to quote from the interview transcript): Sister: “…she wasn't getting better…” which could be interpreted as continuing concerns over the costs of care.

On returning to the village, Ibu Rahmi's symptoms of fever continued. After a further week, she was taken to the village midwife once again. This time the village midwife was not available and the family had to wait (for an unspecified period of time) at her house. When she returned, the midwife referred Ibu Rahmi to a third hospital (hospital C), again approximately 20 km from the village. The family travelled to this hospital in a rented pick-up truck. Sister: “it was difficult to find the vehicle…and it was difficult to find money to pay the cost”.

When the family arrived at hospital C, and after what was described as a “long wait” while payments for care were made, Ibu Rahmi was examined and informed that she had suffered an intrauterine death. Rahmi was then left unattended, for what was described as a long period of time, without consultation, examination or treatment. Sister: “She was not even treated, they just left her, without doing anything…we were panicking…we knew that her child [had] already died.”

Ibu Rahmi and her family were then informed that the hospital was full and that she could not be admitted. At this point in the interview, Ibu Rahmi's mother made a statement to suggest that the family's economic status may have had a bearing on the quality of care received. Mother: “I do not know for sure whether the hospital was full or not. If you have the money, you will immediately get the services. She did not have money.”

Eventually, Ibu Rahmi was referred from hospital C to a fourth hospital (D), 70 km away (a 2–3 hour journey). An ambulance was provided – the first time that emergency transport was mentioned in the interview. However, no health professional accompanied the woman and her family in the ambulance. During the journey to hospital D, the relatives described Ibu Rahmi becoming pale and very weak. Rahmi died in the ambulance en-route to the fourth hospital, unattended and undelivered, calling for her husband.

When asked to identify specific difficulties and delays in the course of events, the family referred to the following: delays in Ibu Rahmi's husband's decision to seek care; the village midwife's unavailability; the cost and unavailability of transport; the distance to hospitals; that they did not know where to go; and that there was no health worker in the ambulance during the final journey. The family felt that the difficulties and delays could have been avoided.

The family referred to the costs of care as the most significant difficulty. Ibu Rahmi was severely ill for approximately 1 month. During this time, the family spent 5 million Indonesian Rupiah (over 250 GBP) on Ibu Rahmi's care, which they had to borrow in part. Despite their poor status, the family made out-of-pocket payments for care, travel and all associated costs.

Barriers to access

This case illustrates the abundance of tertiary level care available in this setting; four referral hospitals feature in the account of events. However, despite its availability, care was still woefully inaccessible. Barriers to access were identified and categorised as follows:

Social and cultural barriers. Ibu Rahmi had a forced marriage at age 16. In addition she suffered severe symptoms for several days before decisions, made by others, were made to seek care. These facts reflect a lack of autonomy and the low social status of Ibu Rahmi, which may have prevented her from accessing healthcare as early as she may have done otherwise.

Geographical barriers. The lack of good quality care in the community made long journeys to treat her illness necessary. Inaccessible and difficult roads are typical terrain in this setting (Fig. 2). These factors are likely to have introduced additional delays in reaching hospitals and put stress on a pregnant woman in the third trimester in a poor health state. It can also be said, therefore, that access to services was constrained on account of Rahmi's geographical location.

Economic barriers. Despite being poor, the family did not have health insurance, a scheme in Indonesia which reduces or waives costs of care for the poor (37). This may have been due to village health workers failing to inform the family of their eligibility for the scheme, or for reasons related to the scheme's complexity and/or acceptability. Concerns over the costs of care resulted in Ibu Rahmi discharging herself from care before she had recovered on two separate occasions. Relatives also indicated a suspicion that their economic status may have negatively affected the quality of care received. Rahmi was quite clearly excluded from access to care on account of her economic status.

Health systems failures. Several, serious health systems failures were apparent, primarily an unmet need for effective community-based maternity services. Access to simple but effective health services in the community would have ensured that Ibu Rahmi's fever was treated, she would have been informed about health insurance, and referred effectively, to a facility where her unborn baby could have been monitored. The hospital receiving her should also have been informed of the referral. The referral hospital(s) should have been adequately staffed and equipped, with procedures for admitting patients who were in the process of arranging health insurance that did not introduce additional delays to their receiving treatment. Finally, the ambulance provided by hospital C should have been staffed and equipped.

Fig. 2.

Geographical barriers to healthcare; typical terrain in the study district.

Medical cause of death

The VA interpretation concluded that the medical cause of death was acute infection. What is not clear is whether the intrauterine death was the cause or result of the infection as there was no information, for example, on the last time that the foetal heart rate was checked. It is important to note that almost any acute condition, infectious or otherwise, would have been worsened, possibly critically, given the multiple barriers described above.

Was the right to health upheld?

The case details are applied to the framework derived from the right to health in Table 1. From this table, it is clear that none of the essential elements of the right to health were upheld. This analysis illustrates that rights-based approaches can identify how and where services can be improved from a human rights perspective. There now follows a discussion on the use of rights-based approaches in practice.

Table 1.

Did health services protect Ibu Rahmi's right to health?

| Criteria for protection of the right to health (22) | Description (adapted, 22) | Comment related to the case of Ibu Rahmi | Protected? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | Functioning facilities, goods and services, as well as programmes, have to be available in sufficient quantity. | Despite the abundance of tertiary level healthcare, it was not functioning, e.g. Ibu Rahmi was left unattended in a poor state of health in hospital C. | No |

| Accessibility | |||

| Non-discrimination | Facilities, goods and services must be accessible to all, especially the most vulnerable or marginalized sections of the population. | Ibu Rahmi's economic and geographical situations, her gender and social status clearly constrained her access to healthcare. | No |

| Physical accessibility | Facilities, goods and services must be within safe physical reach for all sections of the population, especially vulnerable or marginalized groups. | Due to the unavailability of effective community based services, Ibu Rahmi and her family had to undertake long journeys to reach care. | No |

| Economic accessibility (affordability) | Facilities, goods and services must be affordable for all. Payment for healthcare services has to be based on equity, ensuring that services, whether privately or publicly provided, are affordable for all, including socially disadvantaged groups. | Healthcare was clearly unaffordable for the family, e.g. Ibu Rahmi discharged herself from hospital on two separate occasions due to concerns over the costs of care. There was also an expressed suspicion that quality of care was lacking on account of the family's poor status. | No |

| Information accessibility | The right to seek receive and impart information and ideas concerning health issues. | Ibu Rahmi and her family may have made different decisions about healthcare had they been informed about their (apparent) eligibility for health insurance. | No |

| Acceptability | Facilities, goods and services must be respectful of medical ethics and culturally appropriate, sensitive to gender and life-cycle requirements, as well as being designed to respect confidentiality and improve the health status of those concerned. | The final journey in the complicated referral chain demonstrates a grave lack of dignity expressed by hospital D towards Ibu Rahmi, to refer a woman in a critical condition unattended in an unstaffed ambulance. | No |

| Quality | Health facilities, goods and services must be scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality | Several, serious instances of poor quality care were apparent, primarily an unmet need for effective community-based services and effective referral. The referral hospital(s) should have been adequately staffed and equipped, with procedures for admitting patients who were in the process of arranging health insurance that did not delay their care in an emergency. Possibly the most serious health system failures were Ibu Rahmi's rejection from hospital C and the unequipped, unstaffed and unsafe ambulance that she died in. | No |

Discussion

Methodological issues

The case study method allows us to investigate a “contemporary phenomenon within its real life context” (42). The context, for our purposes, is the exclusory processes of the socio-cultural and health system environments with the phenomenon being access to and quality of healthcare. The case study method is often criticised, mainly in terms of its limited capacity for generalisability. The results are intended to be generalisable to “expand and generalise theory” (42). Here, the theory relevant to health planning is enriched and expanded upon.

The right to health in public health planning

The case of Ibu Rhami clearly represents exclusion from access to maternal health services. These barriers, health systems failures and avoidable deaths are typical of maternity in low income settings (44–49). The theoretical framework derived from the right to health was able to identify how and where the right to health was not upheld. It is thus capable of informing health planning. However, whether the right to health can do so in practice is not so clear. We now consider two examples in which human rights have been used to inform health systems and services, and how these mechanisms could be expanded, developed, and used more effectively in future.

Example 1: Policy inputs towards progressive realization

GOI has made significant commitments to human rights, ratifying six of the seven international human rights treaties† derived from the UDHR (50). A National Commission on Human Rights was established in 1993 and a National Action Plan on Human Rights developed for 1998–2003, with a second plan developed for 2004–2009, which includes human rights education and training for government agencies (51). National laws protecting basic human rights also exist (50). However, despite the political commitments, Amnesty International recently reported that “Indonesia has fallen behind in its reporting obligations with respect to many human rights treaties” (52).

In addition, systemic inequity and exclusion were revealed in a recent comprehensive analysis of human rights commitments and their expression in reproductive health services and policies, laws and regulatory frameworks in Indonesia (50). The analysis was undertaken by the World Health Organization and the Indonesian Ministry of Health in 2007. Findings included: irregular provision of EmOC in health facilities; unavailability of drugs, supplies, equipment and blood; fewer facility-deliveries for women with little or no education; low rates of skilled attendance for poor and rural women; impaired access to emergency services in rural areas; high levels of traditional birth attendant-attended delivery in rural areas; and poor or non-existent referral systems in rural areas. Costs were also found to be a “major deterrent for people, especially the poor, to use services” (50).

The findings of the analysis, strikingly similar to those presented here, suggest that despite commitment to the right to health in international treaties, national laws and policies, health inequity and social injustice remain embedded in health systems and services in this context.

Example 2: Enforced accountability

In a recent comprehensive review of the legal enforcement of the right to health, Hogerzeil et al. identify 71 cases from low and middle-income countries where the right to health (in terms of access to essential medicines) was successfully enforced through law courts (53). “In these cases careful litigation … has forced the government to implement its constitutional and human rights treaty obligations and has served the public health cause of improving equitable access … ”. This may seem like a triumph. However, a point of critical importance made by the authors is that when the provision of a good or service is enforced through a law court, when that good or service was previously unavailable for valid reason (e.g. due to high cost or at the expense of other services), can and should law courts over-rule and make these enforcements?

This represents a fundamental discordance in the human rights and public health traditions. Human rights are concerned with the protection and progressive realisation of the rights of the individual, whereas public health is concerned with the collective provision of health services for societies. Configuring health services in response to litigation may, ironically, give rise to further inequity, resulting in services based on the needs of individuals or minority groups rather than populations.

The philosophical roots of the right to health and public health reveal a further fundamental discordance. The right to health is rooted in the medical model of health and healthcare which is clinical and curative in nature (54, 55). This is discordant with the public health tradition; which adopts the social model of health and wellbeing, seeking to improve health by preventing disease (56). Interventions that stem from the right to health (and thus the medical model) will lean towards the provision of therapeutic healthcare services, such as EmOC, rather than social and political reform that are preventative in nature and the address underlying determinants of health, such as education, employment, housing, sanitation, food and nutrition etc.

In practice therefore, the right to health is likely to fail as a public health planning tool. However, human rights are powerful advocacy tools; regarded as the “dominant moral vocabulary of our time” (57). The apparent inability of health policy to express the right to health has led to the consideration of alternative human rights mechanisms to facilitate equitable provision of health services.

The right to development

Contemporary scholars argue that the right to development transcends the individualistic right to health, and has considerable potential to inform the provision of public healthcare from a human rights perspective (55). The Declaration of the Right to Development was adopted by the United Nations in 1986. It states that the right to development is a “comprehensive economic, social cultural and political process which aims at the constant improvement of the well-being of the entire population and of all individuals on the basis of their active, free and meaningful participation in development and in the fair distribution in the benefits resulting therefrom” (58).

The right to development conceives of health as socially constructed and determined and emphasises collective responsibilities of the individual, state and (crucially) the international community “to co-operate with each other in ensuring development…to promote a new international economic order based on sovereign equality, interdependence [and] mutual interest” (58). The right to development advocates for “creating legally enforceable prescriptions for international development policy” and “state responsibility for universal access to primary healthcare, including food education, sanitation etc” (55). Key principles, concepts and modes of operation of the right to development are in their infancy. Despite this, it may be an avenue to inform public health planning from a human rights perspective that addresses the limitations of the right to health.

Conclusion

The pervasive inequities that characterise maternal mortality are reflected at all levels, from individual behaviours, as seen in this case, to the global distribution of mortality between continents. These inequities lead to women experiencing social, economic, cultural and health system barriers to access of healthcare in pregnancy and childbirth, and in the worst scenarios, dying unnecessary deaths as a result. This exclusion represents violations of women's rights to non-discrimination, equity, life and health.

The right to health is likely to be ineffective for public health planning from a human rights perspective. Despite this, human rights are powerful tools that have a potential for equitable health planning and the promotion of social justice. Collective rights, such as the right to development, may provide more suitable frameworks, addressing the underlying determinants of health as well as the immediate medical causes. Indeed, the right to development may provide a means by which to achieve the ethical obligations of the international community to poorer countries, through legally-binding commitments and enforcements where necessary.

We recommend that policies for women's health in pregnancy and childbirth think beyond technical solutions and conceive of health systems as “core social institutions” (59, 60), configured to address deep-seated structural hierarchies and the social determinants of health, foster participation and inclusion and address avoidable mortality, the existing extent of which is nothing short of a moral outrage.

Conflict of interest and funding

All authors state no conflicts of interest. This work was undertaken as part of Immpact, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Department for International Development, the European Commission and United States Agency for International Development. Immpact is an international research programme which also provides technical assistance through its affiliate organisation, Ipact. The funders have no responsibility for the information provided or views expressed in this paper. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Endang Achadi and her team at the University of Indonesia, including Trisari Anggondowati, Kamaluddin Latief and Eko Pambudi for co-ordinating the research, Lupthi Tri Utari for conducting the interview and to Suzanne Cross at the University of Aberdeen who gave comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

LD devised the study design, contributed to data collection, led the analysis and interpretation and drafted the manuscript. PB conceived of the study, devised the study design, supervised the data collection, analysis and interpretation and contributed to versions of the manuscript. SNQ SNQ led the fieldwork and data collection, contributed to data analysis and interpretation and to versions of the manuscript.

Ethics and consent

Written consent was obtained from the next of kin of the deceased for publication of this case report. The research was approved by the Faculty of Public Health Research Ethics Committee at the University of Indonesia (Jakarta, Indonesia) and by the University of Aberdeen (Aberdeen, United Kingdom).

*Pseudonym.

†Indonesia has ratified the following international treaties: the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 1984; the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2005; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 2005; the International Covenant on Torture in 1998; and the International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination in 1999. The remaining international treaty as yet not ratified by Indonesia is the International Convention of the Protection of the Rights of all Migrant Workers and Members of their Families.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: 2007. Maternal mortality in 2005: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank. http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/maternal_mortality_2005/index.html Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Geneva: 2004. Maternal mortality in 2000: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/maternal_mortality_2000/index.html Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Geneva: 2001. Maternal mortality in 1995: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/rhr_01_9_maternal_mortality_1995/index.html Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation. Geneva: 2004. Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant: a joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/2004/skilled_attendant.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paxton A, Maine D, Freedman L, Fry D, Lobis S. The evidence for emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88(2):181–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell O, Graham WJ. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1284–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Bank. Washington: 2004. The Millennium Development Goals for health: rising to the challenges. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/.../15/000009486_20040715130626/Rendered/PDF/296730PAPER0Mi1ent0goals0for0health.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachs JD, McArthur JW. The Millennium Project: a plan for meeting the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 2005;365(9456):347–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations. New York: 2008. UN Millennium Development Goals. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemens MA, Kenny CJ, Moss TJ. The trouble with the MDGs: confronting expectations of aid and development success. World Dev. 2007;35(5):735–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussein J, Braunholtz D, D'Ambruoso L. Maternal health in the year 2076. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):203–04. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starrs AM. Safe motherhood initiative: 20 years and counting. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1130–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook RJ, Dickens BM, Wilson OAF, Scarrow SE. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Advancing safe motherhood through human rights. http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/RHR_01_5_advancing_safe_motherhood/index.html Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook RJ, Dickens BM. Human rights to safe motherhood. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;76(2):225–31. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00568-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman LP. Using human rights in maternal mortality programs: from analysis to strategy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;75(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman LP. Shifting visions: “delegation” policies and the building of a “rights-based” approach to maternal mortality. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002;57(3):154–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedman LP. Human rights, constructive accountability and maternal mortality in the Dominican Republic: a commentary. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82(1):111–14. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fathalla MF. Human rights aspects of safe motherhood. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20(3):409–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruskin S. Rights-based approaches to health: something for everyone. Health Hum Rights. 2006;9(2):5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United Nations. Geneva: 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. General Assembly resolution 217 A (III) of 10 December 1948. http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt P. Geneva: 2005. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Paul Hunt. UN Doc. E/CN.4/2005/51. http://www2.essex.ac.uk/human_rights_centre/rth/docs/CHR%202005.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Geneva: 2000. The right to the highest attainable standard of health. General Comment UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4. http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(symbol)/E.C.12.2000.4.En Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunt P. Geneva: 2006. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Paul Hunt. UN Doc. A/61/338. http://www2.essex.ac.uk/human_rights_centre/rth/docs/GA%202006.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department for International Development. London: 2005. How to note: how to reduce maternal deaths: rights and responsibilities. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/maternal-how.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkins K, Newman K, Thomas D, Carlson C. London: DFID; 2005. Developing a human rights-based approach to addressing maternal mortality: desk review. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/maternal-desk.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.House of Commons International Development Committee. London: 2008. Maternal health fifth report of session 2007-08 Volume I. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmintdev/66/66i.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.UNICEF. Kathmandu: Regional Office for South Asia; 2003. A human rights-based approach to programming for maternal mortality reduction in a South Asian context, a review of the literature. http://www.unicef.org/rosa/HumanRights.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartlett LA, Jamieson DJ, Kahn T, Sultana M, Wilson HG, Duerr A. Maternal mortality among Afghan refugees in Pakistan, 1999–2000. Lancet. 2002;359(9307):643–49. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07808-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartlett LA, Mawji S, Whitehead S, Crouse C, Dalil S, Ionete D, Salama P. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan,1999–2002. Lancet. 2005;365(9462):864–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell O, Ronsmans C. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. Verbal autopsies for maternal deaths: a report of a WHO workshop, London 10–13 January 1994. http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/verbal_autopsies/verbal_autopsies_maternal_deaths.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fantahun M, Fottrell E, Berhane Y, Wall S, Hogberg U, Byass P. Assessing a new approach to verbal autopsy interpretation in a rural Ethiopian community: the InterVA model. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(3):204–10. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.028712. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/84/3/204.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walraven G, Telfer M, Rowley J, Ronsmans C. Maternal mortality in rural Gambia: levels, causes and contributing factors. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(5):603–613. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/bulletin/2000/Number%205/78(5)603-613.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badan Pusat Statistik-Statistics Indonesia (BPS), ORC Marco. Calverton, MD: 2003. Indonesia demographic and health survey 2002–2003. http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pub_details.cfm?ID=439&ctry_id=17&SrchTp=psummary#dfiles Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Government of Indonesia, Ministry of Health, Directorate of Community Health. 1989 429/Binkesmas/DJ/III/89. Jakarta.

- 35.Shankar A, Sebayang S, Guarenti L, Utomo B, Islam M, Fauveau V, Jalal F. The village-based midwife programme in Indonesia. Lancet. 2008;371(9620):1226–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadjimin DT. Assessment of clinical skills of village midwives in ASUH program districts. Jakarta: PATH; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ensor T, Nadjib M, Quayyum Z, Megraini A. Public funding for community-based skilled delivery care in Indonesia: to what extent are the poor benefiting? Eur J Health Econ. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10198-007-0094-x. Published online: 12 January 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makowiecka K, Achadi E, Izati Y, Ronsmans C. Midwifery provision in two districts in Indonesia: how well are rural areas served? Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(1):67–75. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatt L, Stanton C, Makowiecka K, Adisasmita A, Achadi E, Ronsmans C. Did the strategy of skilled attendance at birth reach the poor in Indonesia? Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(10):774–82. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.033472. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/10/06.033472/en/index.html Accessed July 22, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ronsmans C, Endang A, Gunawan S, Zazri A, McDermott J, Koblinsky M, Marshall T. Evaluation of a comprehensive home-based midwifery programme in South Kalimantan, Indonesia. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6(10):799–810. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gillham B. Case study research methods. London: Continuum; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin RK. Case study research. London: SAGE Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keen J. Case studies. In: Pope C, Mays N, editors. Qualitative research in health care. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2006. pp. 112–20. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mavalankar DV, Rosenfield A. Maternal mortality in resource-poor settings: policy barriers to care. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):200–03. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.036715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCaw-Binns A. Safe motherhood in Jamaica: from slavery to self-determination. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19(4):254–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(2):69–79. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liljestrand J. Reducing perinatal and maternal mortality in the world: the major challenges. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(9):877–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–1110. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organization, Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. A report of Indonesia field test analysis. Jakarta: 2006. Using human rights for maternal and neonatal health: a tool for strengthening laws, policies and standards of care. http://www.ino.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/Reproductive_health_Using_Human_Rights_for_Maternal.pdf Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Government of Indonesia. Jakarta: 1998. Indonesia: National Plan of Action on Human Rights. http://huachen.org/english/issues/plan_actions/indonesia.htm Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amnesty International. Indonesia: recommendations to the Government of Indonesia on the occasion of the election of Ambassador Makarim Wibisono as Chair of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. 2005. ASA21/001/2005en. London. http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/ASA21/001/2005/en/dom-ASA210012005en.html Accessed July 22, 2008.

- 53.Hogerzeil HV, Samson M, Casanovas JV, Rahmani-Ocora L. Is access to essential medicines as part of the fulfilment of the right to health enforceable through the courts? Lancet. 2006;368(9532):305–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meier BM, Fox A. Development as health: Employing the collective right to development to achieve the goals of the individual right to health. Hum Rights Quart. 2008;30(2):259–355. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Cambridge: Cambridge Publishers Ltd.; 2007. Public health: ethical issues. http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/go/ourwork/publichealth/publication_451.html Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gready P. Review: The politics of human rights. Third World Q. 2003;24(4):745–57. [Google Scholar]

- 58.United Nations. Geneva: 1986. Declaration on the Right to Development. Adopted by General Assembly resolution 41/128 of 4 December 1986. http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/74.htm Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freedman L. Achieving the MDGs: Health systems as core social institutions. Development. 2005;48(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 60.UN Millennium Project. Task Force on Child and Maternal Health. New York: 2005. Who's got the power? Transforming health systems for women and children. http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/reports/tf_health.htm Accessed July 22, 2008. [Google Scholar]