Abstract

Background

Accurate estimates of the number of maternal deaths in both the community and facility are important, in order to allocate adequate resources to address such deaths. On the other hand, current studies show that routine methods of identifying maternal deaths in facilities underestimate the number by more than one-half.

Objective

To assess the utility of a new approach to identifying maternal deaths in hospitals.

Method

Deaths of women of reproductive age were retrospectively identified from registers in two district hospitals in Indonesia over a 24-month period. Based on information retrieved, deaths were classified as ‘maternal’ or ‘non-maternal’ where possible. For deaths that remained unclassified, a detailed case note review was undertaken and the extracted data were used to facilitate classification.

Results

One hundred and fifty-five maternal deaths were identified, mainly from the register review. Only 67 maternal deaths were recorded in the hospitals’ routine reports over the same period. This underestimation of maternal deaths was partly due to the incomplete coverage of the routine reporting system; however, even in the wards where routine reports were made, the study identified twice as many deaths.

Conclusion

The RAPID method is a practical method that provides a more complete estimate of hospital maternal mortality than routine reporting systems.

Keywords: maternal death, health information system, hospital mortality, missing reports

The under-reporting of maternal deaths is common in both developing and developed countries. Even in countries where all or most deaths are medically certified, institutional maternal mortality can still be grossly underestimated. Hospital studies have shown that routine methods of identifying maternal deaths underestimate the number by one-half to two-thirds (1–4), with the main problem being the misclassification of indirect maternal deaths as non-maternal.

Accurate estimates are important for several reasons: it is necessary to define the scale of the problem of maternal mortality so that adequate resources can be allocated to address it; complete reporting allows all maternal deaths to be audited, thus facilitating relevant changes in policy and practice; and in the context of evaluation, it is essential that any changes attributable to an intervention can be quantified precisely.

The Initiative for Maternal Mortality Programme Assessment (Immpact) project is an international research initiative to strengthen the evidence base on cost-effective and sustainable safe motherhood interventions (http://www.immpact-international.org/). As part of this project, enhanced methods and tools have been developed to measure processes of care as well as health outcomes, including maternal mortality. The objectives of the subcomponent of Immpact reported here was to document the completeness of reporting of institutional maternal deaths in two districts of Indonesia and to assess the usefulness of a new approach developed by Immpact, called Rapid Ascertainment Process of Institutional Deaths (RAPID), in identifying missing deaths.

RAPID is a method designed to identify unreported maternal deaths within health facilities, and to highlight areas for improvement in the reporting of routine institutional deaths. RAPID involves reviewing all the health facility records relating to deaths among women of reproductive age and subsequently identifying pregnancy-related deaths. This process differs from the method routinely used in health facilities to identify pregnancy-related deaths because the death of all women of reproductive age are examined, so the search is not limited to obstetric wards, but includes all wards in the hospital where women may be patients. This minimizes the possibility of missing pregnancy-related deaths that occur outside the obstetric area. RAPID also differs from previous research methods that have examined under-reporting, by taking information from registers to identify pregnancy-related deaths, and only investigating the case notes for deaths that cannot be classified using readily available routine sources.

We also looked at whether it was possible to improve the reporting using existing sources of data, and if so, where such an improvement should be targeted.

Methods

The data collection was conducted during April and May 2005 in the district hospitals of Pandeglang and Serang, in Banten Province, Indonesia. The hospital records of all women aged 15–49 years who had died during 2003 and 2004 were checked for evidence of their pregnancy-related status. Information was extracted from registers and case notes onto pretested forms. Before the study commenced, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Indonesia. Each institution also gave written consent before data collection began.

The definition used to classify deaths as maternal was that the death occurred while a woman was pregnant or within 42 days following the end of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes (5).

Register review

Each team, consisting of one medical doctor and a research assistant, identified all the possible register sources of information on the death of women aged 15–49 years at each of the participating hospitals. In total, there were 12 wards in the two district hospitals where women may have died, and in each ward there were various sources of information about the cases (e.g. ward registers, nurses’ daily reports and death registers). These sources were listed and then searched for deaths, until all deaths of women aged 15–49 years were recorded with details of the diagnosis and cause of death. As deaths could be recorded in more than one register, it was essential that the information obtained was cross-checked between the different registers. Using the information from the registers, as many deaths as possible were classified as likely ‘maternal’ or ‘non-maternal.’ All deaths that could not be classified as either maternal or non-maternal progressed to the next stage of investigation: case note review.

Case note review

Case notes were sought for all the women whose pregnancy-related status at time of death remained unclear following register review. Information on diagnosis, cause of death, treatments, procedures, obstetric history and demographics were extracted with the intention of reclassifying these as maternal or non-maternal deaths. The purpose of this extraction was not to review clinical management or procedures, but simply to gauge the likelihood that a woman was pregnant or recently pregnant when she died. Based on the information extracted from the case notes above, data collectors classified the pregnancy-related status of each woman.

Comparison with other data sources

The total number of maternal deaths reported by the hospitals for the two-year period was collected from the district health offices (DHOs). Informal discussions with both hospital staff and DHO staff were also conducted to obtain a description of the routine reporting practices from the hospitals to the DHOs.

Results

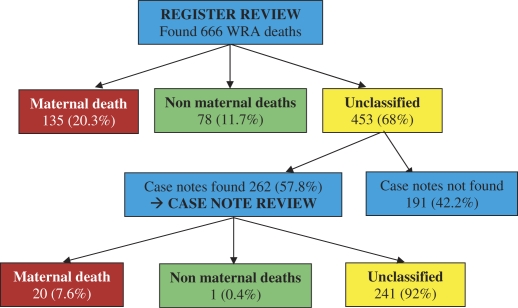

The register review identified 666 adult female deaths, of which 135 were initially classified as maternal deaths (Fig. 1). A further 20 maternal deaths were identified following case note review, giving a total of 155 maternal deaths identified in the two district hospitals using RAPID. Classification for the non-maternal deaths from the register reviews was mostly based on the cases diagnosis, such as ‘severe head injury caused by car accident’ and ‘burns’. Of the 453 cases that remained unclassified after register review, 191 (42.2%) had missing case notes and, therefore, could not be subjected to further examination. Of the 262 case notes that were examined, the vast majority (241 (92%)) could not be classified into maternal or non-maternal, following the review, due to incomplete information.

Fig. 1. .

RAPID process flow and result.

When attempts were made to collect routine figures for maternal deaths, it was found that hospitals were not, in fact, routinely reporting deaths to the DHOs. In practice, the Maternal Child Health unit staff of the DHOs irregularly collected information on maternal deaths directly from the obstetric areas and intensive care unit (ICU); this was not a routine process, occurring once every 1–3 months. From the DHOs annual record, there were a total of 67 maternal deaths reported by the two hospitals’ routine statistics. This number is less than half the number identified by RAPID. The routine reports only include deaths from the obstetric wards, delivery room and ICU. In this study, 86% of the maternal deaths were found in these three clinical areas, with the majority (67.1%) either in the delivery rooms or the obstetric wards (Table 1).

Table 1.

Numbers of maternal deaths by clinical area

| Wards | No. of cases | % |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery room | 61 | 39.4 |

| Obstetric wards | 43 | 27.7 |

| ICU/ICCU | 29 | 18.7 |

| Emergency room | 9 | 5.8 |

| Internal medicine wards | 8 | 5.2 |

| General | 4 | 2.6 |

| Surgery wards | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 155 | 100 |

Table 2 shows how direct and indirect obstetric causes of death are distributed between the clinical areas. Nearly all of the deaths identified from the obstetric wards and ICU were due to direct obstetric causes, while in contrast most of the deaths found on other wards were due to indirect causes (73%).

Table 2.

Number of maternal deaths by direct/indirect cause and by clinical area

| Direct maternal | Indirect maternal | Inconclusive | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wards | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Obstetric | 100 (96.2) | 4 (3.8%) | 0 (0) | 104 (67.1) |

| ICU | 25 (86.2) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (3.4) | 29 (18.7) |

| Other | 3 (13.6) | 16 (72.7) | 3 (13.6) | 22 (14.2) |

| Total | 128 (82.6) | 23 (14.8) | 4 (2.6) | 155 |

Discussion

Despite our limited ability to fairly compare the RAPID results with the hospitals’ routine data (due to incomplete reports from the hospitals), it is reasonable to say that the hospitals’ routine reports missed considerable numbers of maternal death cases. Furthermore, it is likely that the true number of maternal deaths was even higher than the number found in this study. We consider it likely that our method missed additional maternal deaths due to the lack of completeness in recorded information: missing registers, missing case notes or inadequate notes written by health providers. Most diagnoses could be coded, but some could not, as the health care providers only noted symptoms or conditions. Usually, there was inadequate information regarding pregnancy-related status for the cases outside the obstetric wards.

The under-reporting of maternal deaths in the current study was partly due to inadequacies in the coverage of the routine reporting system, which only collected maternal deaths from the delivery room, the obstetric and ICU wards. Approximately 14% of the cases missed from the routine report were identified on non-obstetric wards, and these were mostly indirect maternal deaths, although additional direct deaths were also found. There appeared to be poor understanding among hospital staff that indirect obstetric deaths should be regarded as maternal deaths, and it seems that the possibility of finding maternal deaths on other wards was not considered by the hospital authorities. However, failure to collect data from non-obstetric wards was not the main reason for under-reporting: even on the obstetric and ICU wards, the number of cases identified by RAPID was twice as high as the number in the routine hospital report.

Our findings are similar to those of other studies in both developing and developed countries. A study in Tanzania (6) assessing the completeness of various information sources and the related estimates of maternal mortality found that official statistics only reported two out of 22 maternal deaths occurring in one facility. Another study conducted in France in 1991 (2) found that nearly half of the maternal deaths had not been reported as such on the death certificate, and even those that had, may not have been subsequently registered correctly; as a result, maternal deaths were underestimated by nearly 50%. Another study conducted in Surinam (7) used a reproductive age mortality survey (RAMOS) in five hospitals to identify 85 cases of maternal death. This was 1.3 times higher than the officially reported 65 cases of maternal deaths.

The inadequate reporting of indirect obstetric deaths is also in concordance with other work. A study in Taiwan (8) found that factors contributing to the under-reporting and misclassification of maternal mortality included: care sought for non-obstetric reasons, death from non-obstetric causes, care received in private health facilities and death occurring at home with certification by a non-obstetrician-gynecologist. A World Health Organization (WHO) report (9) shows that out of 66 countries reporting vital registration figures for causes of maternal death over the period 1992–1993, over half (33 countries) reported no indirect deaths at all. Yet the 1997–1999 Confidential Enquiry in the UK found that indirect deaths now account for more maternal deaths than deaths due to direct causes (10).

One of the limitations of the study was that the register review process could not be implemented as simply as had been anticipated. The RAPID retrospective process revealed that there was no standard format for the registers in each ward, which meant that the type of information available varied between registers and the RAPID forms had to be revised. The most important consequence of this was that cases could exist in single or multiple registers, so there was a need to cross-check cases between registers. The identification of duplicate cases between registers had not been adequately considered by the method, as hospital identifiers alone proved insufficient (these were often missing). This meant a great deal of extra work was involved in going back to registers and case notes to check that extractions had not been duplicated. The absence of case note numbers in some registers also meant that cases only recorded in such a register could not be followed up.

The majority of the maternal deaths identified in this study were found at the register review stage; future similar studies in this context could consider removing the case note review element from the method. This would significantly reduce the resources needed to implement the review.

Conclusions and recommendations

The RAPID method found 155 cases of maternal death in the two hospitals for the period 2003–2004. This is more than twice the number of maternal deaths routinely reported by the hospitals. It is likely that the real number of maternal deaths is even higher, as some registers and case notes were missing, and because even where they were available, the information needed to identify a death as pregnancy-related was not always recorded.

RAPID highlights possible misunderstandings in what should be regarded as a maternal death, in particular the inclusion of deaths from indirect (non-obstetric) causes. In other contexts, RAPID has focused on all pregnancy-related deaths (11), and this may be preferable, considering the difficulty in determining whether particular causes of death are exacerbated by pregnancy (12, 13). However, identifying pregnancy-related deaths means that there is greater emphasis attached to the information obtained from case notes, which is a limitation given the incompleteness of data on pregnancy status obtained from this source.

We recommend that DHO and hospital staffs are formally orientated to the definition of maternal death, and that non-obstetric wards are included in the collection of data for routine reports on maternal mortality. The RAPID process is a practical method that can alert hospitals to the magnitude of under-reporting maternal deaths. It also draws attention to shortcomings in the quality and storage of case notes, and provides evidence to initiate improvements in all these areas. We suggest that regular implementation of RAPID, or its integration into the routine hospital information system, could help to monitor improvement in reporting, and call on hospitals to improve the quality and storage of registers and case notes to facilitate this process.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of an international research program – Immpact (http://www.immpact-international.org) funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Department for International Development, the European Commission and USAID. The funders have no responsibility for the information provided or views expressed in this paper. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors.

The authors acknowledge the support from the Banten Province Health Office, Serang and Pandeglang Districts Health Office, Serang and Pandeglang Districts Hospitals and the data collectors too numerous to mention all by name here.

References

- 1.Berg C, Atrash H, Koonin L, Tucker M. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1987–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:161–7. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouvier-Colle MHH, Varnoux N, Costes P, Hatton F. Reasons for the underreporting of maternal mortality in France, as indicated by a survey of all deaths among women of childbearing age. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:717–21. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.3.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atrash H, Alexander S, Berg C. Maternal mortality in developed countries: not just a concern of the past. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:700–5. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00200-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salanave B, Bouvier-Colle MH, Varnoux N, Alexander S, MacFarlane A. Classification differences and maternal mortality: a European Study. MOMS Group. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:64–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. Maternal mortality in 2000: Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/maternal_mortality_2000/challenge.html [cited 7 June 2007]

- 6.Olsen Bjorg E, Hinderaker SG, Lie RT, Bergsjo P, Gasheka P, Kvale G. Maternal mortality in northern rural Tanzania: assessing the completeness of various information sources. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:301–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mungra A, van Bokhoven SC, Florie J, van Kanten RW, van Roosmalen J, Kanhai HH. Reproductive age mortality survey to study under-reporting of maternal mortality in Surinam. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;77:37–9. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao S, Chen LM, Shi L, Weinrich MC. Underreporting and misclassification of maternal mortality in Taiwan. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:629–36. doi: 10.3109/00016349709024602. Available from: http://www.Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fgci?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=92 [cited 14 August 2006] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AbouZahr C. Global burden of maternal death and disability. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:1–11. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg015. Available from: http://bmb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/67/1 [cited 31 July 2006] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis G, Drife J. AbouZahr C, editor. Why mothers die: the confidential enquiries into maternal death in United Kingdom. Global burden of maternal death and disability. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:1–11. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg015. Available from: http://bmb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/67/1 [cited 31 July 2006] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosu WK, Bell J, Armar-Klemesu M, Tornui JA. Effect of the delivery care user fee exemption policy on institutional maternal deaths in the Central and Volta Regions of Ghana. Ghana Med J. 41:118–24. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v41i3.55278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham WJ, Hussein J. Universal reporting of maternal mortality: an achievable goal? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94:234–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006;368:1189–200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]