Abstract

Objective

To study the implications of policy changes on the demand for antenatal care (ANC), HIV testing and hospital delivery among pregnant women in rural Malawi.

Design

Retrospective analysis of monthly reports.

Setting

Malamulo SDA hospital in Thyolo district, Makwasa, Malawi.

Methods

Three hospital-based registers were analysed from 2005 to 2007. These were general ANC, delivery and Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) registers. Observations were documented regarding the introduction of specific policies and when changes were effected. Descriptive analytical methods were used.

Results

The ANC programme reached 4,528 pregnant mothers during the study period. HIV testing among the ANC attendees increased from 52.6 to 98.8% after the introduction of routine (opt-out) HIV testing and 15.6% of them tested positive. After the introduction of free maternity services, ANC attendance increased by 42% and the ratio of hospital deliveries to ANC attendees increased from 0.50:1 to 0.66:1. Of the HIV-tested ANC attendees, 52.6% who tested positive delivered in the hospital and got nevirapine at the time of delivery.

Conclusions

Increasing maternity service availability and uptake can increase the coverage of PMTCT programmes. Barriers such as economic constraints that prevent women in poor communities from accessing services can be removed by making maternity services free. However, it is likely, particularly in resource-poor settings, that significant increases in PMTCT coverage among those at risk can only be achieved by substantially increasing uptake of general ANC and delivery services.

Keywords: health service demand, antenatal care, PMTCT, health policy, Malawi

Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) as part of HIV programmes was introduced in 2001 and has since then been adopted by various countries in Africa and elsewhere (1). Mother to child transmission of HIV (MTCT) can occur during pregnancy, labour, delivery and breastfeeding. Without treatment, around 15–30% of babies born to HIV-positive women will become infected with HIV during pregnancy and delivery. A further 5–20% will become infected through breastfeeding (2–4).

To optimise the effectiveness of PMTCT, WHO promotes a four-pronged comprehensive approach, aimed at improving maternal and child health in the context of an HIV epidemic. This approach promotes routine HIV testing and counselling for pregnant women. If a woman found to be HIV positive wants to continue her pregnancy, she should receive clinical management and Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) for herself, if eligible, or at least antiretroviral (ARV) prophylaxis during labour. For those who want to terminate their pregnancy, safe abortion should be offered where available. Pregnant women should also receive counselling on safe infant feeding choices and appropriately referred for continued care for themselves and their children after delivery (5, 6).

When PMTCT was first introduced, the ‘opt-in’ strategy for HIV testing was generally the way counselling and testing was offered. The ‘opt-in’ strategy is an approach whereby all antenatal care (ANC) clients are encouraged to undergo counselling and testing if they so wish (7). Later, an ‘opt-out’ strategy was adopted by many countries in sub-Saharan Africa (8). The aim was to enable all pregnant women to be screened for HIV infection. Testing should be conducted after a woman is notified that HIV screening is recommended for all pregnant women and that she will receive an HIV test as part of the routine panel of prenatal tests unless she declines (9).

The overall coverage of PMTCT services in sub-Saharan Africa according to WHO (10) is 11% with a range of 8–54%, reflecting varying levels of implementation within each country. The numbers of HIV-infected children in sub-Saharan Africa continue to grow though at different levels (11). This is because of the many challenges that are faced during the implementation of the PMTCT programmes. The challenges include large proportions of home deliveries, shortages of personnel, inadequate supplies of test kits, varying distribution and availability of PMTCT service delivery points, lack of supplementary feeds for women who may opt for non-breast feeding for their infants, and logistical and social implications after testing HIV positive, such as a lack of spousal support and sometimes violence (7, 12–16).

Malawi has an estimated 900,000 people living with HIV/AIDS and the prevalence rate is 14%, almost twice as high as the overall prevalence rate in the sub-Saharan African region (17–20). Life expectancy at birth in Malawi has fallen below 40 years as a consequence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. HIV/AIDS is now the leading cause of death among people aged 20–49 in Malawi (19). HIV prevalence among pregnant women in Malawi ranges from 15 to 19% and PMTCT was initiated in 2003 (21, 22). Furthermore, in 2006, WHO (10) estimated Malawi's PMTCT coverage to be 27%.

The implementation of PMTCT services in Malawi began in a few pilot projects where individual projects used different models, which became difficult to monitor and evaluate in terms of effectiveness of interventions. Subsequently national and local PMTCT guidelines and policies were developed and introduced into the health care system to guide health workers in planning, implementing and evaluating PMTCT services.

This paper describes the experiences of a PMTCT programme during 2005–2007 in rural Malawi and explores how the demand for ANC, HIV testing and hospital delivery was influenced by policy changes during the period.

Methods

Study area

Malamulo mission hospital belongs to the Seventh Day Adventist (SDA) Church located in southern region, in rural Malawi, 65 km south east of Blantyre City in Thyolo District. It was established in 1902 and remains the headquarters of the SDA Church in Malawi. The hospital has 15 mobile sites with two health centres and collaborates with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the district as well as Thyolo District Hospital. The Government and NGOs deliver health care services in Malawi. Among the NGOs, there are health facilities run by Missions but subsidised by the Government and others are privately owned. Health facilities run by faith-based institutions are members of the Christian Health Association of Malawi (CHAM). Malamulo hospital is a member of this organisation. There are 54 health facilities in the district of which 18 belong to the Government and the rest to the NGOs.

Malamulo with a bed capacity of 300, serves as a teaching hospital for allied health workers namely: nurses, medical auxiliaries and laboratory technicians. The hospital serves an estimated population of over 70,000. On average, mothers in this area have 5–8 children, slightly higher than the national fertility rate of 6.2 and HIV prevalence rate among pregnant mothers has been estimated to be 18% (17).

PMTCT in the study area

To complement the efforts of the Government of Malawi, through the Ministry of Health and Population, in fighting against poverty, disease and ignorance, Malamulo implements a comprehensive HIV/AIDS Prevention Programme. Public and faith-based health facilities co-ordinated by the District Health Office (DHO) through Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF) are the PMTCT implementing agencies in the area.

Introduction of PMTCT

PMTCT with an opt-in policy and ART at Malamulo hospital were introduced in July and October 2004, respectively. In 2004, PMTCT was not widely available. Service providers in both public and faith-based health facilities were trained in PMTCT with support from MSF, the Ministry of Health and various NGOs. Following capacity building, all the health centres were upgraded to offer a minimal PMTCT package. The minimal package in this context comprised HIV testing, counselling on feeding options and psychosocial support for HIV-positive mothers. Additionally, women are encouraged to come for HIV testing with their partners. Malamulo hospital remains the referral centre for full-fledged delivery of PMTCT services in the area. The full-fledged services include the minimal package, provision of ART prophylaxis to mothers and their babies, follow-ups and long-term ART. HIV-infected mothers in the health centres are referred to the full-fledged PMTCT services.

Integration of voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) in the ANC unit

Malamulo hospital offered ANC long before HIV testing and counselling services were started. When voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) services were introduced, the services were offered through one central point, the out-patient department (OPD), with the VCT unit using an opt-in approach. In many cases, mothers were lost to follow-up between the ANC unit and the VCT unit. As a local initiative, in March 2005, HIV testing and counselling services were integrated within ANC. In June 2005, management of Sexually Transmission Infections (STIs) was also integrated into ANC.

Opt-out strategy in PMTCT

The opt-out strategy was introduced in January 2006 in Malamulo SDA Hospital PMTCT Programme. This was a Malawi Government initiative and was adopted by public and faith-based health facilities such as Malamulo. The purpose was to minimise the number of HIV-infected women who might transmit HIV infection to their babies. When the opt-in policy was used in PMTCT services, counsellors did one-to-one pre- and post-test counselling, since the client uptake was low. With the introduction of the opt-out strategy, the counsellors’ work load increased. Therefore, the counsellors now conduct the pre-test phase using group counselling, to cope with the growing demand for HIV testing. However, post-test counselling continues to be provided on a one-to-one basis.

Introduction of free maternity services

In October 2006, free maternity services were introduced at Malamulo hospital to cater for its surrounding 15 villages. The move was part of a strategy aimed at reducing maternal and infant mortality rates in Malawi. The Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP), through respective DHOs in the country, is responsible for supporting the strategy. The approach has been extended to faith-based health facilities, as well as public hospitals. International agencies such as UNICEF, UNDP, MSF and others positively support the strategy. The Government of Malawi, through MOHP, is using funds from the UK Department for International Development (DFID) together with tax revenue to manage the continuity of this strategy.

Data collection tools

Three hospital registers were used for data collection from 2005 to 2007. These were general ANC, delivery and PMTCT registers. Policy changes made during the period were also documented.

Data analysis

Data were analysed descriptively based on the three-year period covered by the study. The uptake of ANC, HIV testing and hospital delivery was compared between the different policies introduced during the study period (HIV testing integrated in ANC, opt-out testing and free maternity services). The proportions of HIV-positive tests and HIV-positive women delivering at the hospital and their uptake of nevirapine were also calculated.

Ethical clearance

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from National Health Sciences Research Committee in the Ministry of Health, Malawi. Further, consent was obtained from Malamulo Hospital Administrative Council.

Results

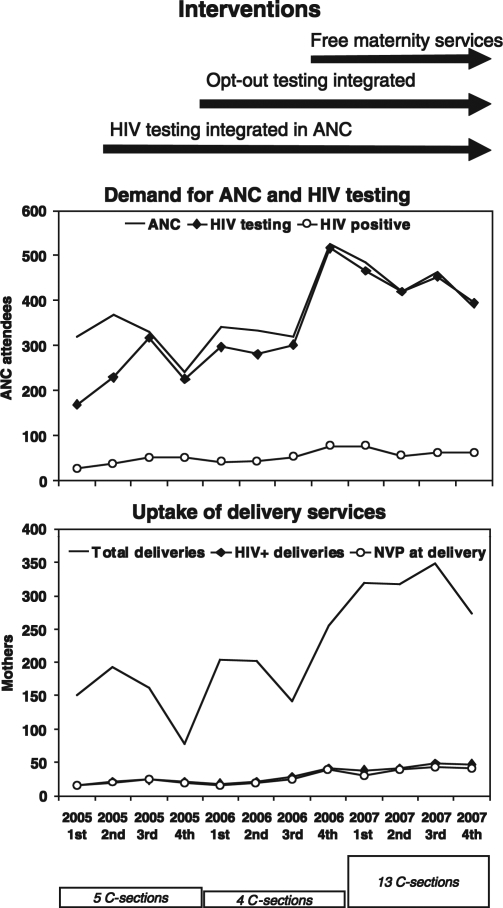

Fig. 1 illustrates women's increasing uptake of maternity services as policy changes to increase access were introduced. A total of 4,528 pregnant women accessed ANC at Malamulo hospital from January 2005 to December 2007.

Fig. 1. .

Time line of interventions introduced in maternity services at Malamulo Hospital, Malawi, 2005–2007, and changes in service uptake.

Before the integration of HIV testing within ANC in March 2005, 196 pregnant mothers accessed ANC, 103 (52.6%) of them underwent HIV testing and 17 (16.5%) tested positive. After March 2005, when HIV testing was integrated within ANC, ANC attendance and the proportion accessing HIV testing generally increased. In this period, 1,063 pregnant mothers accessed ANC, 837 (78.7%) took an HIV test and 148 (17.7%) tested positive. In January 2006, routine (opt-out) HIV testing was introduced within ANC and this again increased both ANC attendance and uptake of HIV testing. A total of 992 women attended ANC, of whom 879 (88.6%) took an HIV test and 137 (15.6%) tested positive. In October 2006, free maternity services were introduced. In this period, 2,277 pregnant mothers accessed ANC, 2,249 (98.8%) took an HIV test and 333 (14.8%) tested positive. The average monthly rates of ANC attendance, HIV testing and HIV-positive results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Average monthly rates of ANC attendance, HIV testing and positivity, hospital deliveries, Caesarean sections, deliveries to HIV+ women and NVP treatment, Malamulo Hospital, Malawi, 2005–2007

| Period | January–February 2005 | March–December 2005 | January–September 2006 | October 2006–December 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy interventions | Pre-intervention | HIV testing integrated in ANC | Opt-out HIV testing in ANC | Free maternity services |

| Duration (months) | 2 | 10 | 9 | 15 |

| ANC attendance/month | 98 | 106.3 | 110.2 | 151.8 |

| ANC HIV tests/month | 51.5 | 83.7 | 97.7 | 149.9 |

| ANC HIV test positives/month | 8.5 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 22.2 |

| Hospital deliveries/month | 58.5 | 46.8 | 61.0 | 100.7 |

| HIV+ hospital deliveries/month | 6.5 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 14.6 |

| HIV+ Caesarean sections/month | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| HIV+ nevirapine treatment/month | 6.0 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 12.9 |

A steady increase in hospital deliveries, including those among HIV-infected mothers and associated with acceptance of nevirapine, together with increasing numbers of delivery by Caesarean section were also observed as these various policy changes were made, as also shown in Fig. 1. A total of 2,645 ANC attendees had hospital deliveries during the study period. Among the HIV positive women, there were Caesarean sections that were carried out in a relatively small proportion (<1%).

In the pre-intervention period, 117 mothers delivered in the hospital of whom 13 (11.1%) were HIV positive and 12 (92.3%) accepted nevirapine. After the integration of opt-in HIV testing within ANC, 468 deliveries occurred in the hospital of whom 70 (15%) were HIV positive and 68 (97.1%) took nevirapine. After routine (opt-out) HIV testing was introduced, 549 mothers had hospital deliveries of whom 67 (12.2%) were HIV positive and 59 (88.1%) took nevirapine. Finally, free maternal services resulted in 1,511 hospital deliveries of whom 219 (14.5%) were HIV positive and 194 (88.6%) mothers took nevirapine. The corresponding average monthly rates for these figures are also shown in Table 1. The overall ratio of hospital deliveries to ANC attendees was 0.50:1 before free delivery was introduced, increasing to 0.66:1 with free delivery. Similarly, in the earlier period, the ratio of HIV-positive hospital deliveries to ANC HIV test positives was 0.50:1, rising to 0.58:1 with free delivery. However, the ratios of HIV-negative hospital deliveries to ANC HIV test negatives were 0.65:1 and 0.67:1, respectively.

Discussion

This study was designed as a descriptive analysis of programme-based activities. It would neither have been feasible nor ethical to incorporate any kind of randomisation to the introduction of the various, potentially life-saving, policy changes implemented within this PMTCT programme, and consequently it is not possible in absolute terms to attribute effects on service utilisation to those policy changes. Nevertheless, the increasing availability and correspondingly larger uptake of services provided within this period are likely to be linked. Since similar interventions were also implemented elsewhere in Malawi, it is not likely that our findings reflect artefacts such as movement of women across catchment areas.

Our study suggests first that integrating HIV testing within ANC increased HIV test acceptance from 52.6 to 78.7%. A similar finding was shown in a study from Barbados, West Indies. In that study, after integrating HIV testing in ANC, HIV test acceptance among ANC attendees increased to 95.8% (23). This may reflect issues such as the integrated approach being convenient, time-saving and hence cost-effective for women, as well as possibly reducing stigma and discrimination since women are not singled out as they access separate HIV services. This implies that comprehensive services in resource-poor settings are necessary to facilitate proper utilisation of the resources and prevent knock-on effects on other public programmes.

The study further revealed that acceptance of HIV testing and counselling among the ANC attendees increased from 78.7 to 98.8% after changing from opt-in to opt-out testing. This increase corresponds with a Zimbabwean study in which 99.9% of ANC attendees accepted HIV testing offered on an opt-out basis (during an initial six-month period), compared with 65% women during the last six months of opt-in testing (24). Thus policies that favour inclusive approaches to testing may increase subsequent access to health services by disadvantaged groups, such as women in PMTCT programmes. Both in Zimbabwe and Botswana, women were satisfied with counselling services within opt-out testing and most (89%) stated that offering HIV testing routinely was helpful (7, 24).

However, it is important to remember that being tested may bring conflict to women whose partners have not consented to it, as found by previous studies (25, 26). This suggests a need to involve male partners and the wider family in PMTCT programmes to overcome barriers. The criticism of PMTCT services is that they are too female-focussed and this has greatly limited their effectiveness and progress. It is also important to remember that male involvement in various aspects of reproductive health care and couple counselling may reduce the challenges women face while accessing maternity services, as has been found in Burkina Faso and Côte d'Ivoire (27, 28).

It is also important to remember that HIV infection in pregnancy raises many difficult ethical, legal and human rights issues as interventions to limit MTCT move beyond delivery. This may leave women in difficult dilemmas or with little choice but to succumb to prevailing situations. It is not easy to conceive and implement standards for protecting reproductive autonomy, as established in the previous studies (29, 30). HIV-positive women experience difficult choices about whether to become pregnant, remain pregnant and manage pressures from partners in the presence of gender inequality. Additionally, families, communities, health care providers and the state may hold different views about the nature of the policies relating to HIV-positive women and their children, with the objective of maintaining health in the context of HIV/AIDS. On the other hand, individual women's rights have to be respected.

Our study also showed that the current response to women's needs in this era of AIDS remains inadequate. Although, ANC attendance rates and hospital delivery rates increased substantially over the period of the study, one-third of ANC attendees still did not deliver in hospital, even given the opportunity of free delivery care. However, it is possible that some women took up free delivery at other institutions. In addition, we cannot know from this study how many pregnant women in the Malamulo catchment area never sought ANC in the first place, nor what the HIV status of that group might be. The PMTCT strategy as the principal framework under which women are easily able to access HIV services reinforces and at times exacerbates the larger challenges they face in accessing much-needed sexual and reproductive health services, including maternal care. PMTCT frameworks require shifts towards ensuring that women's rights and needs, as defined by and enshrined in several global agreements, are more appropriately and adequately met.

Our study suggests that the introduction of free maternity services is of considerable benefit to resource-poor communities such as Malawi, where the majority of women are likely to experience economic difficulties, as also studied elsewhere (31–33). These studies showed that, after introducing free maternity services, more women accessed ANC as well as delivery services. ANC uptake doubled in a Nigerian study, in which women who knew that delivery care would be free of charge were 4.6 times more likely to use ANC services (34). Additionally, hospital deliveries increased from 42.9 to 57.1% after introducing free maternity services. Figures from our study show that, after free delivery was introduced, the ratio of HIV-positive hospital deliveries to ANC HIV-positive test results increased, although there were still large number of HIV-positive women who did not access free delivery in Malamulo hospital. This gap is a challenge and reflects remaining barriers faced by HIV-positive women to access hospital services such as lack of family support and transports (15). The nevirapine uptake during hospital delivery should reach 100%, this is not the case in our study. However, we observed that in 19 cases no information was given on nevirapine in the routine register and therefore conclude that we might underestimate the uptake.

The long-term sustainability of such free delivery policies has to be considered, as has been done in Ghana, where it was found that the main constraint was inadequate funding as a result of inter-sectoral haggling over resources (31, 35). This may be a difficult issue that has to be considered further by programme implementers and policy makers.

This study suggests that opt-out HIV testing, integrated with ANC, plus free maternity services, all led to greater number of HIV-positive pregnancies being delivered in hospital, more doses of antiretroviral prophylaxis being given and modest increase in Caesarean sections. However, these increases were achieved alongside similar increases in service uptake by HIV-negative women. This latter effect is likely to be beneficial to maternal health in general, but at the same time carries very considerable resource implications. If complete coverage of at-risk groups by PMTCT programmes implies, as a pre-requisite, a policy of universal ANC and free hospital delivery, then it is clear that many resource-poor settings will simply not have the capacity (in terms of hospitals, staff, and consumables) for implementation on this scale in the near future. Effective implementation of PMTCT may, therefore, become in effect an argument for a major expansion of health services, rather than developing PMTCT within dedicated, vertical programmes. Barriers to accessing PMTCT services are otherwise likely to be numerous (5, 15, 36).

We therefore conclude that PMTCT programmes need to be strengthened by investing more generally in maternal health services, as well as intensifying education on HIV/AIDS, safe delivery and infant feeding practices, as means of averting HIV/AIDS-related stigmas. Ways of reaching and supporting ANC attendees including HIV-positive women who continue to deliver at home may also be required to further increase coverage of PMTCT services, but in ways that preserve privacy. Involving families, communities and service providers in designing and maintaining appropriate PMTCT service delivery strategies will be essential.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Swedish Institute, Sweden for the financial support without which the study would have been a non-starter. We are also grateful for the support given by the unit of Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Umeå University. Furthermore, we thank the management and staff of Malamulo SDA Hospital, P/Bag 2, Makwasa, Malawi for their support throughout the entire period of carrying out the study. This work was undertaken within the Centre for Global Health at Umeå University with support from FAS, the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (grant no. 2006-1512).

References

- 1.Druce N, Nolan A. Seizing the big missed opportunity: linking HIV and maternity care services in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15:190–201. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Cock KL, Fowler MG, Mercier E, de Vincenzi I, Saba J, Hoff E, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource-poor countries: translating research into policy and practice. JAMA. 2000;283:1175–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newell ML. Current issues in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coovadia HM, Rollins NC, Bland RM. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 infection during exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life: an intervention cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:1107–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manzi M, Zachariah R, Teck R, Buhendwa L, Kazima J, Bakali E, et al. High acceptability of voluntary counseling and HIV-testing but unacceptable loss to follow up in a prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in rural Malawi: scaling-up requires a different way of acting. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1242–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants in resource-limited settings towards universal access. Recommendations for a public health approach; HIV/AIDS Programme. Strengthening health services to fight HIV/AIDS, 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/pmtct/en [cited 11 September 2008]

- 7.Perez F, Zvandaziva C, Engelsmann B, Dabis F. Acceptability of routine HIV testing (“opt-out”) in antenatal services in two rural districts of Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:514–20. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191285.70331.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. Introduction of routine HIV testing in prenatal care–Botswana. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1083–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajunirwe F, Muzoora M. Barriers to the implementation of programs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a cross-sectional survey in rural and urban Uganda. AIDS Res Ther. 2005. Available from: http://aidsrestherapy.com/content/2/1/10 [cited 12 September 2008] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.WHO. Towards universal access, scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector, Progress report 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/mediacentre/universal_access_progress_report_en.pdf [cited 12 September 2008].

- 11.ANECCA. HIV/AIDS overview. African network for care of children affected by HIV/AIDS (ANNECA) USAID. 2008

- 12.Castethon K, Leroy V, Spira R. Preventing the transmission of HIV-1 from mother to child in Africa in the year 2000. Sante. 2000;10:103–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beauregard C, Solomon P. Understanding the experience of HIV/AIDS for women: implications for occupational therapists. Can J Occup Ther. 2005;72:113–20. doi: 10.1177/000841740507200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doherty T, Chopra M, Nkoki L, Jackson D, Greiner T. Effect of the HIV epidemic on infant feeding in South Africa: “when they see me coming with the teens they laugh at me”. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:90–6. doi: 10.2471/blt.04.019448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasenga F, Hurtig A-K, Emmelin M. Home deliveries: implications for adherence to nevirapine in a PMTCT programme in rural Malawi. AIDS Care. 2007;19:646–52. doi: 10.1080/09540120701235651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorsen VC, Sundby J, Martinson F. Potential initiators of HIV-related stigmatization: ethical and programmatic challenges for PMTCT programs. Dev World Bioethic. 2008;8:43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2008.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MDHS. HIV/AIDS prevalence. Zomba: Demography and Social Statistics Division, National Statistics Office; 2004. Malawi Demographic and Health surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarwireyi F. Implementation of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV programme in Zimbabwe: achievements and challenges. Cent Afr J Med. 2004;50:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UNAIDS/WHO. 2004. HIV/AIDS, prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) [Google Scholar]

- 20.MOHP. Facts on HIV/AIDS in Malawi. Ministry of Health and Population. 2005

- 21.MOHP. HIV/AIDS in Malawi. Sentinel Surveillance Report. Lilongwe, Malawi: National AIDS Commission of Malawi, Ministry of Health and Population. 2003

- 22.UNICEF. Children and HIV and AIDS, technical policy documents; cross cutting issues. 2008. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/aids/index_documents.html?=printme [cited 11 September 2008].

- 23.Kumar A, Rochester E, Gibson M. Antenatal voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in Barbados. Success and barriers to implementation. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2004;15:242–8. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892004000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandisarewa W, Stranix-Chibanda L, Chirapa E. Routine offer of antenatal HIV testing (“Opt-out” approach) to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in urban Zimbabwe. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:843–50. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.035188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandrasekaran V, Krupp K, George R. Determinants of domestic violence among women attending a human immunodeficiency virus voluntary counseling and testing centre in Bangalore, India. Indian J Med Sciences. 2007;61:253–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Chang M, Gomes C, Vinocur D, et al. Intimate partner violence prevalence and HIV risks among women receiving care in emergency departments: implications for IPV and HIV screening. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:255–9. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.041541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarker M, Sanou A, Snow R, Ganame J, Gondos A. Determinants of HIV counseling and testing participation in a prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme in rural Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1475–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desgrées du Loû A, Brou H, Djohan G, Becquet R, Ekouevi DK, Zanou B, et al. Refusal of prenatal HIV-testing: a case study in Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire) Sante. 2007;17:133–41. doi: 10.1684/san.2007.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh J, Kalipeni E. Women in Chinsapo, Malawi: vulnerability and risk to HIV/AIDS, Human Sciences Research Council. SAHARA. 2005;2:320–32. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2005.9724857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ngwena Charles G., Cook Rebecca J., guest editors. HIV/AIDS, pregnancy and reproductive autonomy: rights and duties. Dev World Bioethic. 2008;8:iii–vi. doi: 10.1111/J.1471-8847.2008.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witter S, Adjei S. Star–stop funding, its causes and consequences: a case study of the delivery exemptions policy in Ghana. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2007;22:133–43. doi: 10.1002/hpm.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witter S, Arhinful DK, Kusi A, Zachariah-Akoto S. The experience of Ghana in implementing a user fee exemption policy to provide free delivery care. Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15:61–71. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30325-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs B, Price NL, Oeuns S. Do exemptions from user fees mean free access to health services? A case study from a rural Cambodian hospital. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1391–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills S, Williams JE, Adjuik M, Hodgson A. Use of health professionals for delivery following the availability of free obstetric care in northern Ghana. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:509–18. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0288-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James CD, Hanson K, McPake B, Balabanova D, Gwatkin D, Hopwood I, et al. To retain or remove user fees? reflections on the current debate in low- and middle-income countries. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2006;5:137–53. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200605030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindgren T, Rankin SH, Rankin WW. Malawi women and HIV: socio-cultural factors and barriers to prevention. Women Health. 2005;41:69–86. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]