Abstract

Background

For understanding epidemiological transition, Health and Demographic Surveillance System plays an important role in developing and resource-constraint setup where accurate information on vital events (e.g. births, deaths) and cause of death is not available.

Methods

This study aimed to assess existing level and trend of causes of 18,917 deaths in Matlab, a rural area of Bangladesh, during 1986–2006 and to project future scenarios for selected major causes of death.

Results

The results demonstrated that Matlab experienced a massive change in the mortality profile from acute, infectious, and parasitic diseases to non-communicable, degenerative, and chronic diseases during the last 20 years. It also showed that over the period 1986–2006, age-standardized mortality rate (for both sexes) due to diarrhea and dysentery reduced by 86%, respiratory infections by 79%, except for tuberculosis which increased by 173%. On the other hand, during the same period, mortality due to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases increased by a massive 3,527% and malignant neoplasms by 495%, whereas mortality due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and injury remained in the similar level (12–13% increase).

Conclusion

The trend of selected causes of death demonstrates that in next two decades, deaths due to communicable diseases will decline substantially and the mortality due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) will increase at massive proportions. Despite Matlab's significant advances in socio-demographic indicators, emergence of NCDs and mortality associated with it would be the major cause for concern in the coming years.

Keywords: epidemiological transition, mortality, verbal autopsy, cause of death, Matlab, Bangladesh

Health transition has been one of the most important features of demographic changes in the twentieth century. It is a complex process comprising demographic, epidemiological, and health care transitions that manifested in rising life expectancy at birth due to changes in the fertility, mortality, and morbidity profile of a population (1, 2). The general shift from acute infectious and deficiency diseases to chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is usually referred to as the epidemiological transition, which reflects changes in the pattern of mortality, particularly in relation to the cause of death (COD), as well as changes in morbidity (3). Over five decades or so from 1950, Asia has witnessed a dramatic demographic and epidemiological transition, affecting the population growth rate, expectation of life, and health systems (4). It has significant implications for the environmental, economic, social, and health consequences in national level, especially for the developing countries.

The World Health Organization (WHO) forecasts that in the next two decades there will be dramatic changes and transitions in the world's health needs, as a result of epidemiological transition. At present, lifestyle and behavior are linked to 20–25% of the global burden of disease, which would be increasing rapidly in poorer countries (5). Moreover, NCDs are expected to account for seven out of every 10 deaths in the developing regions by 2020, compared with less than half today. Injuries, both unintentional and intentional, are also growing in importance and by 2020 could rival infectious diseases as a source of ill-health (5).

For understanding demographic and epidemiological transitions, Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) plays an important role in developing and resource-constraint setups where accurate information on vital events (e.g. births, deaths) and COD is not available. The primary objective of this study was to assess existing level and trend of mortality by causes of deaths for people living in rural Bangladesh. In this paper, the authors analyzed COD data from a rural demographic and health surveillance area, collected through standard verbal autopsy (VA) tools, for the period 1986–2006. The standardized VA tool was developed by INDEPTH Network according to ICD-10 COD list, which facilitates comparison of results from different countries (6) to effectively capture the epidemiological transition that took place over last two decades in rural Bangladesh. On the available mortality data, the authors also fitted trends for specific causes of death and projected future scenarios in terms of mortality burden.

Methods

Study area

The data used in this study came from a rural area in Matlab, where ICDDR,B maintains the HDSS since 1966. Matlab is located 55 km in the southwest of the capital city Dhaka. Area under HDSS was divided into halves in late 1977. One half gets government health services like any other rural areas of Bangladesh (called the government services area) and another half gets high-quality ICDDR,B primary health care services in addition to the government health services (7, 8). Analysis of COD includes data of the government services area only, in order to examine the epidemiological transition in last two decades in a typical setup of rural Bangladesh.

Data sources

HDSS used the one-page Death Form for all age groups, with particular emphasis on child and maternal deaths since 1966. In 1986, the Death Form was revised, consisting of three parts; identification of the deceased, large space for writing signs, and symptoms that led to death and medical consultation prior to death, and space for medical assistant (MA) for writing possible COD and ICD-9 code for it. Experienced field research assistants (FRAs) with at least 10 grade education, but no formal training in medicine were trained in two sessions followed by a refresher session after one year later to record precisely timing, duration, and gradation of each of the symptoms preceding death, particularly of children and women of reproductive age in Bangla. FRAs conducted interview in colloquial Bangla, and wrote descriptive statements in Bangla, preserving local idioms and refraining from approximate translations. They interviewed the caretakers of the deceased; usually mothers in cases of child death and spouses (or close relatives; sons and daughters, brothers or sisters in absence of spouses) in cases of adult and elderly deaths. The interview with caretakers lasted for 10–20 minutes depending on emotional state of the caretakers and duration of the last illnesses and medication. The interview took place on an average of 22 days after the date of death. This VA tool continued till 2003 parallel to the WHO standard VA questionnaires (for neonatal, child, and adult deaths). For this new VA procedure, selected FRAs were given extensive training on WHO VA tools to collect additional VA data, which include modular questions on injury, chronic disease, last disease symptoms, life style factors, medication, and hospitalization, apart from the open death history. The differences in VA methods used before and after 2003 are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Major features of verbal autopsy methods used in Matlab surveillance area

| Indicators | VA used during 1986–2003 | VA used from 2003 and onwards |

|---|---|---|

| VA tool | One page death form with space to write signs and symptoms of diseases or conditions that led to death (open death history) | Three VA tools (for neonates, children, and adults) with open death history and modular questions on injury, chronic disease, last disease symptoms, life style factors, medication, and hospitalization |

| Interviewers | All field research assistants (FRAs) with education 10 grade or more grade | Selected FRAs were trained on VA; all FRAs were promoted to the supervisor position in 2004 |

| Recall period | Four weeks | 6–12 weeks |

| Coder | Medical assistant (MA) with three years training in medicine and long experience in VA | Same MA |

| Cause of death (COD) assessment | MA reviews the open history of death to assign COD | MA reviews the open death history, modular questions, and medical records to assign COD |

Assessment of cause of death (COD)

In order to restrict the number of persons assigning COD, the responsibility of assigning COD of all ages lies with a full-time medically trained person (i.e. MA). The MA, with three-year training in medicine, was trained to review descriptions of signs and symptoms leading to death and health records, and to assign possible underlying COD and visit deceased family to collect additional information when required to assign COD. The MA uses his own judgment evolved from his experience and training to assign main (or underlying) COD (9, 10).

The MA had to select a single three-digit code from a list of 97 possible codes, derived from the ‘basic tabulation list’ of the WHO International Statistical Classification of Disease (ICD-9), Injuries and Causes of death (11). Many of the codes proposed by the WHO basic tabulation list were not retained because they would be irrelevant in the context of Matlab area and lay reporting. New codes were introduced to account for frequent combination of primary and underlying causes. Only one code is used for COD. This modified procedure is expected to ensure greater consistency in coding, and ease supervision and offer a greater choice of codes, minimize forced compliance, and allows greater flexibility in classification. The MA also reviews the new VA forms and assign COD ICD-10 codes.

Supervision and quality control

Matlab HDSS has in-built data quality control checks at every stage of the field data collection procedures since 1966. For example, field supervisors during their visits, review record of the Family Visit Card; inquire about all past events; and record any missing events onto standard forms (9). Supervisors and FRAs meet fortnightly to review activities and to discuss problems for finding feasible solutions. Apart from the surveillance team, a quality control team of two female FRAs, check independently completeness of recording vital events in the field. Both the physician and the principal investigator of the HDSS project supervised the MA's work. At regular intervals, death forms are randomly drawn and checked, and difficult cases are reviewed and provided feedback. The same MA was responsible for assigning causes of death for whole period of 1986–2006, and using a single, trained coder is regarded as effective as two (or multiple) coders that is currently widely accepted (12). Though the VA coder in Matlab HDSS is not a physician, despite extensive training and experience in this field, the inter-coder variation found in Matlab to be substantially high. This makes comparison of COD difficult across time within the area and hence the use of the same MA throughout the period eliminates inter-coder variation and produce consistent and comparable (not necessarily accurate) COD. However, ‘learning by doing’ over time may incur some inconsistency in COD, which cannot be controlled.

Ethical issues

HDSS longitudinally records all vital events including VA, respecting people's sentiment and maintaining strict confidentiality of the recorded information. HDSS is a project approved by the Ethical Review Committee of ICDDR,B. HDSS information is used for carrying out research leading to policy issues and interventions.

Data analysis

HDSS recorded 18,917 deaths and their cause in the Government services area during 1986–2006. HDSS annual reports present WHO age-standardized cause specific mortality fraction (CSMF) (13) for this period. For trend analysis, major causes of deaths were grouped into broad causes as follows:

Communicable diseases (CDs): diarrhea, dysentery, tuberculosis (TB), and respiratory diseases; other communicable includes Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) related diseases, jaundice, meningitis, hepatitis, skin, and veneral diseases.

NCDs: malignant neoplasm; diseases of circulatory diseases (cardiovascular diseases and stroke); digestive diseases including liver diseases; and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) including chronic bronchitis and asthma.

Accident/injury: accident, drowning, suicide, murder, and homicide.

In this study, above broad causes of death were focused and for further analyses, other causes like maternal and perinatal condition (including nutritional cause), miscellaneous, and unknown causes were not used. Exponential models were fitted on the mortality data available for 1986–2003 and future scenarios upto 2025 were forecasted on the basis of exponential models.

The exponential regression model used for analyzing trends of major causes of death is:

In order to estimate the parameters of above exponential model, the following linear regression model is fitted using the available age-standardized mortality rates for selected causes of death over 1986–2006:

The parameter estimates, including respective standard errors and test of significance, were obtained using Microsoft Excel's Data Analysis and Solver tool packs (14, 15).

Findings

The pattern of cause of mortality experienced a massive change from acute, infectious, and parasitic diseases to non-communicable, degenerative, and chronic diseases during the last 20 years. It may be mentioned that proportion of miscellaneous decreased gradually from 20% in 1986 to 5% in 2006.

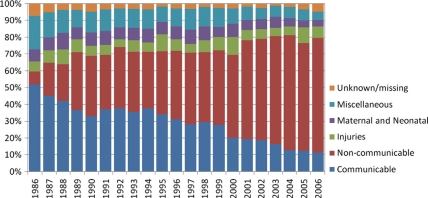

NCDs (viz. malignant neoplasm, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (CVD), digestive diseases, and COPD, etc.) comprised only 8% of total deaths in 1986 (Fig. 1), compared to 52% deaths due to CDs (viz. diarrhea, dysentery, TB, and respiratory infections, etc.). In 1996, proportion of deaths due to NCDs increased to 41% and deaths due to CDs declined to 31%. Later in 2006, NCDs comprised of a massive 68% of all deaths, whereas deaths due to CDs decreased to 11% of total deaths. Matlab HDSS data suggested that over 1986–2006, proportion of deaths due to NCDs increased by nearly nine-fold, whereas during this period, deaths due to injuries (including suicide and homicide) remained stable around 7%, maternal and neonatal (including nutritional) deaths declined from 7 to 4%, and deaths due to unknown/unspecified causes declined from 7 to 5%.

Fig. 1. .

Change in broad causes of death for both sexes in Matlab Government service area, 1986–2006.

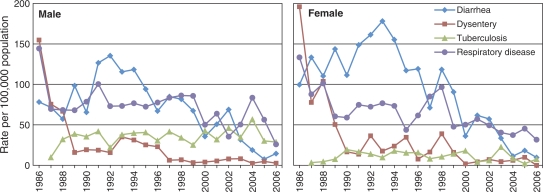

Trend analysis of specific causes of CDs (Fig. 2) demonstrates that in 1986, death rates due to dysentery and respiratory diseases among males was around 150 deaths per 100,000 population. Dysentery fell substantially just after 1988 and now remained under three deaths per 100,000 population in 2006, while deaths due to respiratory infections among males remained stable around 80 deaths per 100,000 population till 2000, and declined to 26 deaths per 100,000 in 2006. Diarrheal deaths increased from 78 deaths per 100,000 population to 135 deaths per 100,000 in 1992, and then dramatically declined by 89% to reach the level under 15 deaths per 100,000 in 2006. Among the CDs among males, only TB remained at the same level (around 30 deaths per 100,000) over the period 1988–2006 and showed a slight upward trend over time.

Fig. 2. .

Deaths due to major communicable diseases, Matlab Government service area, 1986–2006.

Initially, deaths among females due to diarrhea and dysentery were higher than that of males – the age-standardized mortality rates for the aforementioned causes started from a level of 100 and 200 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively, in 1986. In the later years, the mortality rates declines following a similar pattern of males and by 2006, reached similar level in 2006. The deaths due to TB among females were considerably lower than males, which remained stable over the period 1990–2006.

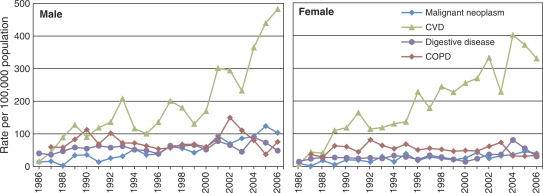

The mortality rates by specific NCDs (Fig. 3) demonstrate an opposite scenario compared with the CDs. Among males, cardiovascular diseases (including diseases of circulatory system, viz. hypertension, ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, and other cardiovascular) increased by 30-folds (from 16 deaths per 100,000 population in 1986 to 483 deaths per 100,000 in 2006). Deaths due to malignant neoplasm (viz. cancer) also increased massively by 640% (14 – 103 deaths per 100,000 population) over the period 1986–2006. Compared with CVD and malignant neoplasms, deaths due to digestive diseases and COPD among males remained somewhat stable (increased by 21 and 27%, respectively) over the aforementioned period.

Fig. 3. .

Deaths due to major non-communicable diseases, Matlab Government service area, 1986–2006.

Among females, the age-standardized mortality rates due to CVD (and diseases of circulatory system) also increased massively from seven deaths to 330 deaths per 100,000 population during 1986–2006. Deaths due to COPD among females remained flat around 50 deaths per 100,000 population during 1994–2001 and reduced to a level of 34 deaths per 100,000 population since 2003, whereas deaths due to digestive diseases among females doubled and malignant neoplasms quadrupled (from 10 to 40 deaths per 100,000) during last 20 years. In contrast to males, mortality levels due to selected NCDs among females remain considerably lower throughout the period 1986–2006.

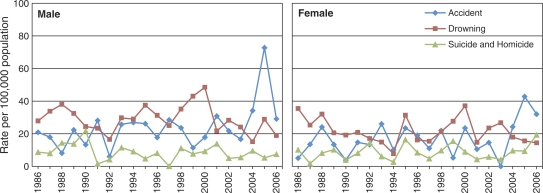

Deaths due to accidents and injuries (including homicide and suicide) among males and females remained similar over the period 1986–2006. Drowning remained a major COD under this category for both males and females, which considerably declined from a level around 40 deaths per 100,000 in 2000 to under 20 deaths per 100,000 in 2006. Mortality due to accidents among males is slightly higher than that of females and accidental deaths among males show an upward trend since 1999. In 2005, a marine vessel accident in nearby Gomti river was the reason for peaks (Fig. 4) in mortality rates due to accident among males and females. The current level of mortality due to suicide and murder/homicide is higher among females in Matlab Government service area.

Fig. 4. .

Deaths due to accident/injury, Matlab Government service area, 1986–2006.

In order fit trends to existing causes of death data from 1986–2003 period and project future scenarios, exponential models were used. Analysis of existing trends using exponential models (see Table 1) demonstrates that in next 20 years, the Government service area under Matlab surveillance will witness statistically significant decline in deaths due to CDs except TB. On the contrary, Matlab will experience a significantly massive increase in deaths due to NCDs like CVD, malignant neoplasm, and digestive diseases over next two decades. The trend analysis also demonstrates that except accidental deaths, mortality due to drowning and suicides will also gradually, though not significantly, decline in the next 20 years.

The parameter estimates for exponential models on mortality due to selected causes of death in Table 1 showed that the exponential regression models for selected causes of death fitted well, in terms of R 2 value and significance of the exponential coefficient, except for TB, COPD, accident, drowning, and suicide and homicide. Year-to-year variation and ‘flat’ nature of progression for aforementioned causes of death could be the main reason for not fitting the models well.

Assuming that there will be no major change or disruption in the existing mortality trends in the future, the parameter estimates for the fitted exponential models on mortality from Table 2 were used for projecting scenarios for selected causes of deaths and are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Parameter estimate of fitted exponential regression models on age-standardized mortality rates of selected causes of death, Matlab Government service area, 1986–2003

| Causes of death | Intercept (a) | Beta (b) | SE (b) | p-Value | R2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicable diseases | |||||

| Diarrhea | 272.7 | –0.053 | 0.02 | 0.004 | 41 |

| Dysentery | 164.1 | –0.169 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 76 |

| Tuberculosis | 35.2 | 0.030 | 0.02 | 0.095 | 17 |

| Respiratory disease | 191.5 | –0.036 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 49 |

| Other communicable | 76.9 | –0.067 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 63 |

| Non-communicable diseases | |||||

| Malignant neoplasm | 23.9 | 0.099 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 82 |

| CVD | 92.8 | 0.120 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 68 |

| Digestive disease | 69.6 | 0.017 | 0.01 | 0.036 | 25 |

| COPD | 114.3 | 0.016 | 0.01 | 0.188 | 11 |

| Accident/injuries | |||||

| Accident | 31.5 | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.885 | <1 |

| Drowning | 51.9 | –0.001 | 0.01 | 0.925 | <1 |

| Suicide and homicide | 18.0 | –0.018 | 0.02 | 0.377 | 5 |

Table 3.

Current and forecasted mortality rates due to selected causes of death, Matlab Government service area, 2006–2025

| Age-standardized mortality rate (per 100,000 population) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes of death | 2003 | 2006 (current) | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2025 |

| Communicable diseases | ||||||

| Diarrhea | 65.25 | 24.3 | 77.2 | 59.3 | 45.6 | 35.1 |

| Dysentery | 12.8 | 2.75 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Tuberculosis | 57.08 | 36.37 | 71.5 | 82.9 | 96.0 | 111.3 |

| Respiratory disease | 91.04 | 57.71 | 80.4 | 67.2 | 56.0 | 46.8 |

| Other communicable | 17.62 | 81.88 | 15.5 | 11.1 | 8.0 | 5.7 |

| Non-communicable diseases | ||||||

| Malignant neoplasm | 118.43 | 143.11 | 259.2 | 425.9 | 699.7 | 1149.5 |

| CVD | 460.26 | 812.75 | 1660.4 | 3028.6 | 5523.9 | 10075.3 |

| Digestive disease | 81.48 | 79.27 | 104.4 | 113.6 | 123.7 | 134.6 |

| COPD | 184.11 | 109.64 | 169.2 | 183.6 | 199.3 | 216.2 |

| Accident/injuries | ||||||

| Accident | 16.65 | 61.06 | 33.6 | 34.0 | 34.5 | 34.9 |

| Drowning | 50.79 | 33.29 | 53.5 | 53.8 | 54.1 | 54.4 |

| Suicide and homicide | 9.54 | 26.74 | 11.6 | 10.6 | 9.6 | 8.8 |

By using the parameter estimates from Table 1, age-standardized mortality rates for selected causes of death were projected up to 2025 in Table 3. The fitted exponential trends demonstrated that dysentery (R 2=76%), followed by diarrhea (R 2=41%), will decrease considerably in the coming years. The models forecasted that by 2015, deaths due to dysentery and diarrhea would come down to 1 and 59 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively, and by 2025, 0 and 35 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively. The exponential model fitted (R 2=49%) for deaths due to respiratory diseases forecasts that age-standard mortality rate due to respiratory diseases will be 67 per 100,000 population in 2015 and 47 deaths per 100,000 population by 2025. Exponential model to TB mortality, with low goodness of fit (R 2=17%) and loosely significant exponential coefficient (p=0.10), projected that mortality level due to TB would gradually increase to 83 deaths per 100,000 population in 2015 and to 111 deaths per 100,000 population in 2025.

The fitted exponential models to age-standardized mortality due to selected NCDs (see Table 3) forecasted that deaths due to digestive diseases (R 2=25%) would rise steadily over the next two decades, with levels of 114 deaths per 100,000 in 2015 and 134 deaths per 100,000 in 2025. The projected scenarios for the other major NCDs also projected that deaths due to CVD will increase (R 2=68%) up to 3,029 deaths per 100,000 by 2015 and to a massive 10,075 deaths by 2025 in Matlab Government service area, whereas deaths due to malignant neoplasm will also increase (R 2=82%) to 426 deaths per 100,000 by 2015 and 1,150 deaths per 100,000 by 2025. The fitted model showed that only death due to COPD (R 2=11%) will remain stable at the level of around 200 deaths per 100,000 over next two decades.

Exponential models on selected causes of deaths under accidents/injuries category projected that (see Table 3) accidental deaths (R 2<1%) and drowning (R 2<1%) will remain stable around 34 and 10 deaths per 100,000, respectively, over the next two decades. Deaths due to suicide and homicide (R 2=5%) will gradually decrease to 11 deaths per 100,000 by 2015 and nine deaths per 100,000 population by 2025. In general, the goodness of fit for the exponential models fitted to accident/injury data are relatively poor compared with other major communicable and NCDs, except TB and COPD.

Discussion

The study is based on COD derived from open-ended death history reported by lay respondents and recorded by lay (non-medically trained) field workers. The Center's emphasis on maternal and child-health issues may have resulted in inadequate information on adult and elderly deaths that led to a high proportion of deaths classified as ‘unspecified’ or ‘senility’ or misclassification in COD. However, uniformity in recording VA and assessment of COD during 1986–2003 is the strength to examine changes in the pattern of CSMFs over the years. Moreover, VA COD is reasonably accurate in broader cause categories in India, China, and South Africa (16–18). Results demonstrated a substantial change in CSMFs from CDs to NCDs. Earlier it was documented that physicians had the highest rates of disagreement between them in assigning causes of death from reported complications of premature or small-for-date neonates in Matlab (19). VA on less common disease symptoms could also be less accurate as both lay interviewers and lay respondents can be less aware of signs and symptoms of less common infectious diseases. While neoplasm and cardiovascular diseases were the leading causes of death of older adults (age 45–59 years), ‘senility’ was reported as a major COD of elderly (aged 60 years and over) people. Structured modular questionnaire and intensive training of lay field staff may improve assessment of COD and reduce percentage of deaths attributed to senility and other unspecified causes.

The demographic transition that took place over last 40 years in the Matlab surveillance area resulted in a stable low growth rate due to lowering of both births and deaths compared with 1966 level, and demographic data indicate that Matlab has apparently entered to third stage of demographic transition (20). Despite considerable decline in overall mortality in terms of crude death rate from 12.2 to 6.4 per 1,000 population in Matlab Government service area (7, 20), epidemiological transition is also well advanced in a typical rural setup like Matlab.

Historically Matlab was a cholera endemic area, a significant proportion of deaths, particularly infant and child deaths was due to diarrheal diseases followed by acute respiratory infections. Results show that over the period 1986–2006, mortality rate due to diarrhea and dysentery reduced by 86% and respiratory infections by 79%. On the other hand, mortality from TB increased by 173%. Improvement in primary health care services; wide use of oral rehydration solution, high EPI coverage and improvement in water and sanitation conditions, and maternal education may have contributed to the reductions of infant and child mortality in the study area (21). This paper demonstrated that over the period 1986–2006, age-standardized mortality rate (for both sexes) due to diarrhea and dysentery reduced by 86%, respiratory infections by 79%, except for TB which increased by 173%.

On the other hand, during 1986–2006, mortality due to CVD increased by a massive 3,527% and malignant neoplasms by 495%, whereas mortality due to COPD and injury remained in the similar level (12–13% increase). Rate of increase was not uniform, male mortality due to CVD increased by nearly 30-folds and malignant neoplasm by 6.4 folds compared to female mortality due to CVD and malignant neoplasm increased by 46-folds and 3-folds, respectively. Mortality due to other major NCDs like digestive diseases stably increased by 1% each year among males and was doubled among females. COPD remained stable for both the sexes, with a much higher level among males than females. There may be some misclassification of COD, but most misclassification occurs within NCD category itself (22). In this study, VA coder could not assign specific cause (ill-defined) to 5–20% of the deaths. In China, VA misclassified a few deaths due to cerebrovascular disease, IHD, COPD, and diabetes as ill-defined causes (16). If this is true for this study, some of the deaths with ill-defined cause were due to NCD, and VA had underestimated, to an extent, incidence of NCD deaths, which bring catastrophic economic consequences for the family members. In this study very few deaths were attributed to the diabetes, which is believed to be a major non-communicable cause in elderly in Bangladesh.

Although very few studies were conducted on epidemiological transition in Bangladesh, the massive shift in mortality from CDs to non-communicable ones over the last 20 years demonstrated in this paper was in agreement with earlier studies. A recent study demonstrated that (23) over the period 1987–2002, the prevalence of morbidity due to communicable diseases (CDs) declined from 58 to 35%, while NCD morbidity increased from 33 to 57%. The study also found that the specific NCDs causing substantially high number of disability or death during this period were: asthma, rheumatic fever, chronic pulmonary disease, and strokes. The estimates of mortality levels for selected chronic and NCDs and their projections in Matlab surveillance area could be biased due to introduction of WHO standard VA in 2003. This COD assessment error, however, occurred more during the later part of the period. About 70% of all deaths in 2006 were attributed to NCDs.

The massive increase in mortality due to NCD, particularly CVD in the study period is a reality suggesting that some changes had happened in diet and lifestyle in this rural population. An earlier study found that intakes of carbohydrate, animal protein, and smoking were significantly positively associated with the prevalence of general hypertension, even after controlling for body-mass index and other nutrients (24). The study also found that the animal protein pattern was strongly positively associated with markers of socio-economic status and the prevalence of cigarette smoking, which indicated to the conception that an epidemic of hypertension leading to CVDs first affected members of the higher socio-economic status, then toward the general population, who are changing from a lower risk to a higher risk lifestyle characterized by diets rich in fat, a sedentary lifestyle, and smoking (24). Outside Bangladesh, several studies documented the on-going epidemiologic transition in a number of Asian countries – China and urban areas of India already found to be in advanced stage of transition with predominant NCDs, with the highest mortality caused by CVD at ages below 50 years (25, 26). Prevalence of diabetes was also found to be increased steeply over last two decades in south-Asian countries, including China, India, and Pakistan (27, 28). Studies found out that urbanization, high-calorie diet, higher socio-economic status, and sedentary lifestyle are the major determinants for increase in NCDs in the Asian communities (25–28).

Conclusion

The study area like any other rural parts of Bangladesh, experienced advanced epidemiologic transition and the health sector should be preparing itself to cater to the health need of the growing NCD patients. It can be possible through establishing proper diagnostic facilities and referral system by incorporating such provisions in the next Strategic Investment Plan and updating the health policy accordingly. Allocation of more budgets to the health sector and facilitation of the non-traditional financing mechanism like community health insurance scheme could play an important role in easing access to health services. The policy makers should also devise provisions of behavior change activities to prevent major NCDs (viz. diet, exercise, periodic screening of risk factors) and treatment of selected NCDs into the Essential Services Package (ESP), in addition to the existing services.

Acknowledgements

The Matlab Health and Demographic Surveillance System was funded by ICDDR,B and its donors which provide unrestricted support to the Centre for its operations and research. Current donors providing unrestricted support include: Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (EKN), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and Department for International Development, UK (DFID). We gratefully acknowledge these donors for their support and commitment to the Centre's research efforts.

References

- 1.Caldwell JC, Findley S, Caldwell P, Santow G, Cosford W, Braid J, et al., editors. Canberra: Health Transition Centre, Australian National University; 1990. What we know about health transition: the cultural, social and behavioural determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omran AR. Epidemiological transition: theory. In: Ross JA, editor. International encyclopedia of population. Vol. 1. New York: The Free Press; 1982. pp. 172–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahdan MH. The epidemiological transition. East Mediterr Health J. 1996;2:8–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escovitz GH. The health transition in developing countries: a role for internists from the developed world. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:499–504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Glossary of globalization, trade and health terms. Available from: www.who.int/trade/glossary/en/index.html [cited 20 July 2008] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baiden F, Bawah A, Biai S, Binka F, Boerma T, Byass P, et al. Setting international standards for verbal autopsy. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:569–648. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Ginneken J, Bairagi R, de Francisco A, Sarder AM, Vaughan P. Dhaka: ICDDR,B; 1988. Health and demographic surveillance in Matlab: past, present and future. Special Publication No. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.ICDDR,B. Dhaka: ICDDR,B; 2009. Health and demographic surveillance system–Matlab, Vol. 41. Registration of health and demographic events 2007. Scientific Report, No. 106. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimicki S, Nahar L, Sarder AM, D'Souza S. Dhaka: ICDDR,B; 1985. Demographic surveillance system – Matlab: cause of death reporting in Matlab, Bangladesh, Vol. 13. Scientific Report No. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Souza S. Dhaka: ICDDR,B; 1981. A population laboratory for studying disease process and mortality – the demographic surveillance system. Matlab, Bangladesh. Special Publication No. 13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1977. Manual of the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death, Ninth revision, Vol. 1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi R, Lopez AD, MacMahon S, Reddy S, Dandona R, Dandonaa L, et al. Verbal autopsy coding: are multiple coders better than one? Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:51–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.051250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inove M. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series No. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bissett BD. Automated data analysis using excel. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh S, Diamond D. Non-linear curve fitting using microsoft excel solver. Talanta. 1995;42:561–72. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(95)01446-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang G, Rao C, Ma J, Wang L, Wan X, Dubrovsky G, et al. Validation of verbal autopsy procedures for adult deaths in China. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:741–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gajalakshmi V, Peto R. Verbal autopsy procedure for adult deaths. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:748–50. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandramohan D, Rodrigues LC, Maude GH, Hayes RJ. The validity of verbal autopsies for assessing the causes of institutional maternal deaths. Stud Fam Plann. 1998;29:414–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fauveau V, Wojtyniak B, Chowdhury HR, Sarder AM. London: Centre for Population Studies, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1991. Assessment of cause of death in the Matlab Demographic Surveillance System, Vol. 26; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.ICDDR,B. Registration of health and demographic events 2006. Scientific Report No. 103. Dhaka: ICDDR,B; 2008. Health and demographic surveillance system-Matlab, Vol. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhuiya A, Streatfield K. Mother's education and survival of female children in a rural area of Bangladesh. Popul Stud. 1991;45:253–64. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and contribution of risk factors: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molla A. Epidemiological transition and its implications for financing of health care: a case study in Bangladesh; The annual meeting of the Economics of Population Health: Inaugural Conference of the American Society of Health Economists, Madison, 4 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Factor-Litvak P, Howe GR, Parvez F, Ahsan H. Nutritional influence on risk of high blood pressure in Bangladesh: a population-based cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1224–32. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.5.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy S, Yusuf S. Emerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Circulation. 1998;97:596–601. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ôunpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–53. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correa-Rotter R, Naicker S, Katz IJ, Agarwal SK, Valdes RH, Kaseje D, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic transition in the developing world: role of albuminuria in the early diagnosis and prevention of renal and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int. 2004;66:S32–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.09208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker KL, Buranapin S. Nutrition and aging in developing countries. J Nutr. 2001;131:2417S–23S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.9.2417S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]