Abstract

Statement of Translational Relevance

Although benzodiazepines have been used clinically for over 50 years, their application as a form of cancer therapy is largely unexplored. Here we show that lorazepam, a benzodiazepine commonly prescribed to treat anxiety disorders and acts on both central and peripheral receptors, inhibits prostate cancer cell growth and survival. Our studies further elucidate the mechanism by which Translocator Protein (TSPO) antagonists alter cancer cell function. Antagonists for TSPO are already used in the clinic for other indications and demonstrate very minor side effects. Because lorazepam is a commonly prescribed FDA-approved drug, the translation of our preclinical results to the prostate cancer patient population could be readily achieved. Our studies could lead to a significant change in the management of prostate cancer by providing a treatment option with minimal toxicity for use after failure of androgen-deprivation therapy and could ultimately prevent prostate cancer deaths.

Purpose

The transmembrane molecule, Translocator Protein (TSPO) has been implicated in the progression of epithelial tumors. TSPO gene expression is high in tissues involved in steroid biosynthesis, neurodegenerative disease and in cancer and overexpression has been shown to contribute to pathologic conditions including cancer progression in several different models. The goal of our study was to examine the expression and biological relevance of TSPO in prostate cancer and demonstrate that the commonly prescribed benzodiazepine lorazepam, a ligand for TSPO, exhibits anti-cancer properties.

Experimental Design

Immunohistochemical analysis using tissue microarrays was used to determine the expression profile of TSPO in human prostate cancer tissues. To demonstrate the effect of benzodiazepines (lorazepam and PK11195) in prostate cancer, we utilized cell proliferation assays, apoptosis ELISA, prostate cancer xenograft study, and immunohistochemistry.

Results

TSPO expression is increased in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, primary prostate cancer, and metastases compared to normal prostate tissue and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Furthermore, TSPO expression correlates with disease progression, as TSPO levels increased with increasing Gleason sum and stage with prostate cancer metastases demonstrating the highest level of expression among all tissues examined. Functionally, we have demonstrated that lorazepam has anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic properties in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, we have shown that TSPO overexpression in nontumorigenic cells conferred susceptibility to lorazepam-induced growth inhibition.

Conclusion

These data suggest that blocking TSPO function in tumor cells induces cell death and denotes a survival role for TSPO in prostate cancer and provide the first evidence for the use of benzodiazepines in prostate cancer therapeutics.

Keywords: TSPO, Prostate Cancer, PBR, benzodiazepine, lorazepam, PK11195

Introduction

Translocator Protein (TSPO), previously known as the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor, is a transmembrane molecule that is best known for transporting cholesterol across the mitochondrial membrane for cell signaling and steroid biosynthesis (1, 2). TSPO has been shown to be overexpressed in numerous malignancies, including those of the breast, prostate, colon, ovary, and endometrium (3–7). Furthermore, a correlation has been shown between TSPO overexpression and the progression of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers (8). Functionally, TSPO has been shown to take part in the regulation of apoptosis through its interactions with the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (9, 10). TSPO also plays a role in cell proliferation, as a correlation between TSPO expression and cancer cell proliferation has been observed in human astrocytomas (11) and breast cancer (12) while TSPO antagonism inhibits cell proliferation (13–16).

As its former name suggests, the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor, now called TSPO, has the ability to bind benzodiazepines with relatively high affinity (17). Benzodiazepine receptors are found in both the central and peripheral nervous system, but unlike its central-type counterpart, TSPO has no anxiolytic or anticonvulsant effects and has distinct mechanistic and pharmacologic properties (18, 19). Binding studies have shown that lorazepam and PK11195, the benzodiazepines used in this study, can inhibit binding of the high affinity TSPO ligand Ro5-4864 (20). Although lorazepam is classically considered a ligand of the central-benzodiazepine receptor, the study by Park et al suggests that it can also bind TSPO. The effects of lorazepam in peripheral tissue, such as the prostate, have yet to be explored.

Initial reports identified elevated expression of TSPO in rat R-3327 Dunning AT-1 prostate tumors (4). Follow-up studies demonstrated that orchiectomized Dunning G rats also had increased TSPO density in prostate tumors, however treatment with testosterone repressed TSPO ligand binding, suggesting a role for testosterone in TSPO expression levels in these hormone-sensitive prostatic tumors (21). TSPO density is decreased in the male genital tract but not the heart after castration, indicating TSPO levels are affected in organs regulated by the trophic influence of testosterone (22). While downregulation of TSPO during androgen depletion occurs in normal male rat urogenital tissues, the receptor is upregulated in genitourinary cancer cells with androgen withdrawal. Immunohistochemical studies found significantly increased TSPO expression in human prostate cancer tissues when compared with benign prostatic hyperplasia and normal tissues (8). However, despite these promising findings, few studies have investigated the role of TSPO in prostate cancer further.

In this study, we observed increased expression of TSPO in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer tissue compared to normal, noncancerous tissue. We show that PK11195 and lorazepam, a benzodiazepine commonly prescribed to treat anxiety disorders, exhibits anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic actions in prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Our studies suggest that TSPO may be an excellent therapeutic target for prostate cancer and demonstrates that benzodiazepines may provide a treatment option with minimal toxicity for use after failure of androgen-deprivation therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Human prostate cancer cell lines PPC-1, LNCaP and DU145 were maintained in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen; Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). LNCaP and DU145 cells were purchased from ATCC and the PPC-1 cell lines is a subline of PC3 prostate cancer cell line (23). LN05, an androgen-deprived LNCaP cell line, was maintained in RPMI without phenol red with 10% charcoal stripped FBS and 1% P/S. The human prostate cancer cell line LAPC4 was maintained in IMDM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. The androgen-deprived LAPC4 cell line, LA98, was maintained in IMDM without phenol red (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% charcoal stripped FBS and 1% P/S. Human embryonic kidney cells, HEK293, and human cervical cancer cells, HeLa, were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S.

Tissue Microarrays and TSPO Immunocytochemistry

For these studies we used prostate tissue arrays (progression array, metastasis array and PSA failure array) from the in-house Western Pennsylvania Tumor Bank to directly compare TSPO staining intensity in the tissue specimens. Samples from benign kidney, breast, colon, testis and adrenal are included as positive and negative tissue controls for TSPO and are sampled in duplicate with sections at diagonally opposite ends of the block to eliminate positional staining artifacts.

There were 16 cases of normal donor prostates, 24 of non-neoplastic prostatic tissues adjacent to malignant glands (NAT), 24 of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), 22 prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), 86 prostatic adenocarcinoma (PCa), and 86 metastatic prostate carcinoma specimens (Met) from 35 patients with 25 separate sites of metastasis. Samples of benign testis and adrenal were also included on each TMA as positive controls for TSPO expression (n=2 each).

Immunohistochemical stains were performed on five-micron sections of TMA blocks. The sections of all the groups were deparaffinized and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol incubations. Heat induced epitope retrieval was performed using decloaker, followed by rinsing in TBS buffer for 5 minutes. Slides were then loaded on Dako Autostainer. The primary anti-TSPO (working dilution 1:350) was a polyclonal rabbit antibody (Trevigen; Gaithersburg, MD). The immunolabeling procedures were carried out according to manufacturers' instruction using Dako Envision Labeled Polymer-HRP anti rabbit (Dako; Glostrup, Denmark). Slides were then counterstained in hematoxylin, step dehydrated and coverslipped. A prostate optimization MRA block was used as positive control for each antibody. Both the extent and intensity of immunopositivity were considered when scoring the expression of TSPO. Briefly, the intensity of positivity was scored from 0 to 3 as follows: 0 as non-stained, 1 as weak, 2 as moderate, and 3 as strong as positive control. The extent of positively stained cells was estimated using the same 0–3 scale. Semiquantitative analysis of TSPO expression in the human tissues were carried out in a blinded fashion by a board certified GU pathologist (AP) using a 4-tier scoring method for intensity (0,1,2,3) added to percent expression in epithelia [intensity + (% × 3)]. The final composite score (0–6) was determined after adding the intensity and extent of positivity in the respective lesions.

Western Blot Analysis

Human prostate cancer cells (PPC-1, DU145, LAPC4, LA98, LNCaP, LN05), HEK293, and HeLa cells were lysed in lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, 135mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1% Triton-X). Human hepatocyte lysate was obtained from Dr. Steven Strom, University of Pittsburgh and Jurkat cell lysate was obtained from Upstate (now Millipore; Billerica, MA). Protein concentration was determined and an equal amount of protein (10 μg) was separated on 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Proteins were electrotransferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore; Billerica, MA) and blocked in 4% milk in PBST (PBS supplemented with 0.2% Tween20) for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunodetection of TSPO was carried out using the goat anti-TSPO polyclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals; Littleton, CO) at a dilution of 1:1000 at 4°C overnight. The membrane was washed in PBST and incubated with a donkey anti-goat secondary HRP-linked antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) at a dilution of 1:2000 for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was visualized using ECL (Amersham Life Sciences; Piscataway, NJ). Membranes were blotted for β-actin (Sigma Aldrich; St Louis, MO) at a dilution of 1:4000 as a control for protein loading.

Cell Viability Assay

PPC-1 human prostate cancer cells were plated at 5 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates (Falcon-BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) and adhered overnight at 37°C. The next day cells were treated with TSPO antagonists PK11195 (Sigma-Aldrich; St Louis, MO), lorazepam (Sigma-Aldrich) at varying concentrations (0.1μuM-100μM) or vehicle (0.1% ethanol or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), respectively) for 48 hours at 37°C. The cells were then incubated for 4 hours with 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrasodium bromide (MTT) (Chemicon; Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The optical density was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm using the SpectraMax M2e absorption spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA). MTT assays were repeated in three independent experiments.

Cell Proliferation Assay

PPC-1 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in 6-well plates. Cells adhered overnight and were then treated with TSPO antagonists PK11195 or lorazepam at 10μM, 50μM or 100μM or vehicle for 72 hours. Cells were trypsinized and cell proliferation was measured by direct cell counting using a Coulter Counter (Beckman-Coulter; Fullerton, CA). Cell proliferation assays were repeated in 3 independent experiments.

Apoptosis ELISA

PPC-1 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in 6-well plates. Cells adhered overnight and were then treated with TSPO antagonists PK11195 or lorazepam at 10μM, 50μM or 100μM or vehicle for 18 hours. A spectrophotometric apoptosis ELISA was used to quantify histone-associated DNA fragments present in the cell lysates according to manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics; Indianapolis, IN). Briefly, the standard solution and samples were added to the wells of a 96-well plate coated with a monoclonal antibody. After incubation, the plate was washed, and an enzyme-labeled antibody was added. After further incubation, the plate was washed again and treated with the substrate and the optical density was determined at 405 nm using the SpectraMax M2e absorption spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices). Apoptosis assays were repeated in 3 independent experiments.

Annexin V Staining and Flow Cytometry

Human LNCaP and PPC-1 prostate cancer cells were plated in 100 mm plates and once cells reached approximately 70% confluence, cells were treated with 50μM or 100μM PK11195 TSPO antagonist or vehicle for 18 hours. For flow cytometry using the Annexin V assay, cells were collected and double-stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated Annexin V (PharMingen; San Diego, CA) and propidium iodide (PI). Cells were counted and Annexin V was added according to the manufacturer's recommendations to 1 × 105 cells for each condition (in 100 μl of Annexin V binding buffer) in duplicate with PI used at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Annexin V positive cells were considered apoptotic and their percentage of the total number of cells was calculated. Cells taking up vital dye PI were considered dead. Samples of 10,000 cells were analyzed by FACScan flow cytometer with LYSIS II software package (Becton Dickinson).

Transfection

A vector containing TSPO cDNA (pCMV6-TSPO) was purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD) and the empty vector was used as a negative control for all experiments. HEK293 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA), stable clones selected by neomycin resistance and TSPO expression levels were analyzed by immunoblot analysis as described above. The HEK293 cells overexpressing TSPO will be referred to as HEK293 TSPO.

HEK293 TSPO Susceptibility to Lorazepam

HEK293 and HEK293 TSPO cells were plated at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates. Cells adhered overnight and were then treated with 50μM lorazepam for 48 hours. Following treatment, cells were trypsinized and counted using a Coulter Counter. These experiments were repeated in 3 independent experiments.

TSPO Antagonism in Human Prostate Cancer Xenografts

PPC-1 cells were grown to 80% confluence in growth media. Cells were dissociated with trypsin, washed twice in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) and 20 male athymic nu/nu mice (Charles River Laboratories; Wilmington, MA) received subcutaneous flank injections of 1 × 106 cells per 100 μl of HBSS. Mice were weighed and tumors were measured with calipers twice a week and tumor volumes were calculated (tumor volume = length × width × height × 0.5236). When the average tumor size reached 100-200 mm3 the mice were stratified into 2 groups (10 mice per arm) and given either lorazepam or vehicle (DMSO). Treatments were administered intraperitoneally at 40mg/kg lorazepam or vehicle 7 days a week for ~35 days. Once a mouse's tumor burden reached 2 cm the mouse was sacrificed and the tumor was removed, weighed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin for analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Five-micron sections of paraffin-embedded tumors were quenched in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 minutes and stained following citrate-steam antigen retrieval with TEC-3 Ki-67 (M7249; Dako, Caripinteria, CA) or PECAM (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) primary antibodies. A biotinylated secondary antibody was used, followed by streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogen (K0690; Dako). For labeling apoptotic nuclei, tissues were deparaffinized and treated with 0.3% H2O2 for 30 minutes to eliminate endogenous peroxidases. The DNA nick labeling reaction was carried out using 50U/ml Klenow (Roche Diagnostics), 2mM dNTP (Promega: Madison, WI) with 0.5nM biotin-16-dUTP (Roche Diagnostics) in buffer A (0.05M Tris, pH 7.5; 5mM MgCl2; 0.058mM MESNA; and 0.05% bovine serum albumin) for 60 min at 37C. The sections were then rinsed in PBS and incubated with 50mg/ml Peroxidase-Z-Avidin (Zymed Laboratories; San Francisco, CA) in PBS with 0.5% BSA for 30 min at 37°C. After rinsing, the labeling was visualized using a diaminobenzidine solution (90mg DAB (Sigma) in 150ml PBS, 600ul NiCl, + 60ul H2O2 30%). As a positive control, adjacent tissue sections were treated with DNaseI (0.1 mg/ml). All of the tissues were scored in a blinded fashion.

Tumor Growth Model

A nonlinear mixed effects approach to examine tumor growth longitudinally was implemented to describe the growth characteristics of the PPC-1 cells under vehicle and lorazepam treated arms. This was done using the NONMEM V 1.1 (Icon development solutions, Ellicott City MD USA). Specifically, the nonlinear mixed effects approach allowed the data to be probed with respect to both the shape of the growth curves, with exponential, gompertz and logistic models tested and compared using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The mean PPC-1 cell volume was used for the calculations (3.43 ± 0.03 μm3). The Gompertz Model provided the best fit:

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using a two-tailed Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA unless otherwise specified. Results were considered to be statistically significant when P values were determined to be <0.05.

Results

TSPO Expression is Increased in Prostate Cancer

To determine relative expression levels of TSPO in human tissue, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of prostate cancer tissue microarrays (TMA). As shown in Figure 1A & B-G, we observe significantly increased expression of TSPO in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (average score: 3.0/6), primary prostate cancer (4.1/6), and prostate cancer metastases (4.8/6) compared to normal donor (2.0/6), normal tissue adjacent to tumor (2.1/6), and benign prostatic hyperplasia (1.8/6). Furthermore, TSPO expression increases with progression, as prostate cancer metastases have the highest expression levels. Testes and adrenals are steroidogenic tissues documented as having relatively high TSPO expression and were therefore used as positive controls.

Figure 1. Increased TSPO expression in prostate cancer.

(A) relative expression of TSPO by IHC in normal donor prostate, normal prostate tissue adjacent to tumor (NAT), benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), primary prostate cancer (PCa), and prostate cancer metastases (met) by scoring of TMA cores. TSPO expression is significantly (p<0.05) increased in PIN, PCa, and PCa metastases, compared to normal prostate tissue and BPH. (B-G) representative results of IHC staining of TSPO in normal donor prostate (B) NAT (C), BPH (D), PIN (E), PCa (F), and PCa metastasis (G). (H) total cell lysates (10ug) were used for Western blot analysis to determine expression levels of TSPO in human prostate cancer cell lines PPC-1, DU145, LAPC4, LA98, and LNCaP, LN05, compared to human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293), human T lymphocytes (Jurkat), human cervical cancer cells (HeLa), and human liver hepatocytes (Hep). * indicates p<0.05

Increased expression of TSPO is also observed in vitro with elevated expression in prostate cancer cell lines PPC-1, DU145, LAPC4, LA98, and LNCaP, LN05, compared to a nontumorigenic, human embryonic kidney cell line (HEK293), T lymphocytes (Jurkat), a tumorigenic cervical cancer cell line (HeLa), and human hepatocytes (Hep), (Figure 1H). It is important to note that the 36kDa band observed is not unique to our studies, as higher molecular weight bands have previously been reported in western blots using antibodies against TSPO (24, 25).

Analyses of prostate tumor Gleason sum and stage were carried out to identify whether TSPO is altered with disease progression. TSPO levels were high in all tumor specimens compared to normal adjacent glands and TSPO expression increased with increasing grade and stage in the TMA specimens (Table 1). TSPO levels in adenocarcinoma were significantly higher than PIN or NAT when matched for stage except in stage II specimens in which PIN regions demonstrated TSPO levels equivalent to regions of NAT. There was also a significant change in TSPO levels in patients with high Gleason sum (Table 1).

Table 1.

TSPO immunostaining in human prostate tissue by Gleason, stage and PSA failure.

| Gleason | <6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.02 ±0.93 (n=39) | 4.16 ±0.95 (n=81) | 4.48 ±0.90 (n=42) | 4.58 ±1.11* (n=25) | |

| Stage | PCa | PIN | NAT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | 3.97 ±0.86 (n=19) | 3.01 ±1.06 (n=15) | 2.85 ±0.92 (n=18) | |

| III | 4.14 ± 1.04 (n=59) | 3.52 ±0.95 (n=19) | 2.58 ±0.93 (n = 32) | |

| IV | 4.46 ±0.88* (n = 23) | 3.63 ±0.51 (n = 3) | 2.65 ±0.79 (n=19) | |

| PSA failure | 4.17 ±0.97 (n=50) | 3.34 ±0.98 (n=19) | 2.66 ±0.88* (n=35) | |

| disease free | 4.02 ±1.13 (n=78) | 2.91 ±0.75) (n=17) | 2.07±0.82 (n=23) | |

indicates statistical significance <0.05. Gleason 9 specimens showed higher TSPO levels than Gleason sum 6 and 7 but not Gleason 8. Stage IV PCa had higher TSPO than both stage II and III tumors.

There were 25 separate organ sites for prostatic tumor metastasis analyzed from 35 patients. All sites of PCa metastases demonstrated high TSPO levels compared to primary PCa, PIN or NAT (data not shown). The highest TSPO levels were found in prostate metastatic lesions to the bladder (5.7 ± 0.65) and seminal vesicles (5.5 ± 0.21) while slightly lower levels were present in metastases to the soft tissue next to bone (3.7 ± 0.52) as well as the thyroid (4.3 ± 1.3) and scapula (4.4 ± 0.48) but all PCa metastases had higher TSPO levels than NAT (2.0±0.82), PIN (3.0 ± 0.85) and all metastatic sites but one had higher TSPO (soft tissue next to bone) than organ confined PCa (4.0 ±1.11).

Our assessment of TSPO expression in the PSA failure array, shows a significant difference in the NAT glands of patients with PSA failure compared with the NAT of patients who remain disease free (Table 1). However there was no difference in the PIN or adenocarcinoma expression of TSPO in the primary tumors of patients with PSA failure compared to disease free patients. There was also no change in TSPO levels with age in prostate tumor specimens (data not shown). The PSA failure array did not contain specimens from patients that have remained disease free, so the samples on the progression array were used for this comparison and matching control tissue was used as comparison between TMAs to assure IHC scoring remained the same across separate arrays.

TSPO Antagonism has Anti-Proliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects In Vitro

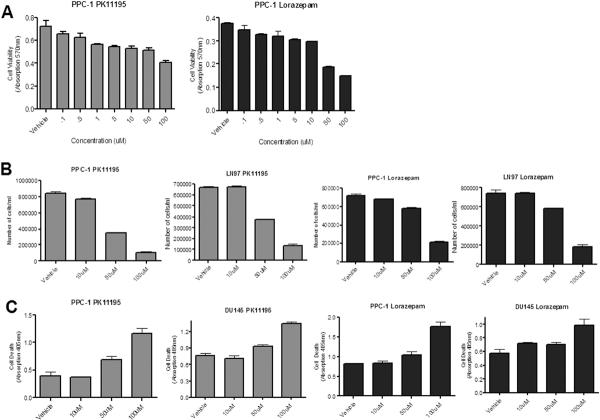

We began our preliminary functional studies to identify cancer cell sensitivity to TSPO receptor blockade by screening a series of potential TSPO antagonists, including benzodiazepines temazepam, lorazepam, estazolam, and Ro5-4864, and the isoquinoline carboxamide PK11195. Among all of the compounds examined, the benzodiazepine lorazepam and PK11195 demonstrated the most significant antagonistic properties based on cell proliferation assays. To further examine the antagonistic effects of these compounds, PPC-1 human prostate cancer cells were treated with varying concentrations of PK11195 or lorazepam (0.01-100μM) for 48 hours and cell viability was analyzed using an MTT assay. Figure 2A demonstrates that treatment with PK11195 or lorazepam significantly decreases cell viability at micromolar concentrations. Additionally, we observe a decrease in cell number following treatment with either PK11195 or lorazepam (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. TSPO antagonism decreases cell proliferation and increases apoptosis in prostate cancer cells in vitro.

(A) MTT assay following 48 hour treatment of human prostate cancer cells, PPC-1 with PK11195 or Lorazepam (0.1uM-100uM) or vehicle (EtOH or DMSO, respectively). (B) direct cell counting of PPC-1 and LN97 cells treated with varying concentrations of PK11195 or Lorazepam or vehicle for 48 hours. (C) Cell death ELISA following 18 hour treatment of PPC-1 and DU145 cells with varying concentrations of PK11195 or Lorazepam or vehicle. * indicates p<0.05

In other cancer in vitro models, TSPO antagonists have been shown to reduce cell survival through apoptosis and we assessed whether the decrease in cell proliferation with treatment with PK11195 or lorazepam is through induction of an apoptotic pathway. Prostate cancer cells were treated with PK11195, lorazepam or vehicle for 18 hours. An apoptosis ELISA was used to quantify histone-associated DNA fragments present in the cell lysates. Figure 2C shows a dose- dependent increase in apoptosis following treatment with PK11195 or lorazepam. Using annexin V staining and flow cytometry, we also observed a significant dose-dependent increase in apoptosis in the PPC-1 and LNCaP cells treated with PK11195 (data not shown).

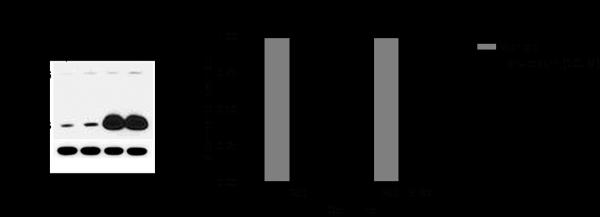

Overexpression of TSPO Receptor Modulates Effect of TSPO Antagonism

Overexpression of TSPO in HEK293 cells (Figure 3A) did not significantly alter growth rate (data not shown) but significantly increased susceptibility of the cells to TSPO antagonism (Figure 3B). HEK293-TSPO cells, vector only controls and wildtype HEK293 cells were treated with 50 μM lorazepam or PK11195 and cell counts analyzed after 48 hrs. Lorazepam (Figure 3B) and PK11195 (not shown) significantly reduced cell numbers in HEK293-TSPO cells but not in the controls. However, PK11195 also induced significant cell death in wildtype and vector control cells indicating potential off-target effects.

Figure 3. Increased Susceptibility to Lorazepam in 293 Cells Overexpressing TSPO.

(A) Western blot analysis of 293 cells overexpressing TSPO (293-TSPO A/B) compared to the parental cell line (293) and empty vector control cells (293-C). (B) Percent of 293 and 293-TSPO cells treated with 50uM lorazepam (black bars) compared to vehicle treated cells (grey bars). * indicates p<0.05

TSPO Antagonism has Anti-Proliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects In Vivo

To examine the in vivo efficacy of TSPO inhibition, 20 athymic male mice received subcutaneous flank injections of prostate cancer cells. When tumors reached ~100-200 mm3, the mice were randomized into two treatment groups (10 mice per arm) such that each mouse received a daily dose of either 40 mg/kg lorazepam or vehicle (1% DMSO). The tumor measurements demonstrate a divergence in tumor growth between lorazepam and vehicle treated mice: by week nine, lorazepam treated mice exhibited a significantly smaller average tumor volume (2682 ± 539 mm3) when compared to vehicle treated mice (7392 ± 346 mm3) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. TSPO antagonism decreases cell proliferation and increases apoptosis in prostate cancer cells in vivo.

(A) Average tumor volume over time of athymic nude mice bearing PPC-1 xenograft tumors treated daily with Lorazepam (40mg/kg) or DMSO. Tumor volume was measured twice weekly as described in the Materials and Methods section. Data are shown as means + the standard error. (B) immunohistochemical staining of lorazepam or vehicle treated PPC-1 xenograft tumors for cell proliferation (ki67), microvascular density (CD31), and apoptosis (TUNEL). Bars graphs represent average values of positive signal counted in four random fields (40X magnification) * indicates p<0.05

A nonlinear mixed effects approach to examine tumor growth longitudinally was implemented to describe the growth characteristics of the PPC-1 cells under vehicle and lorazepam treated arms. The gompertz model resulted in the lowest AIC and objective function values by approximately 25 points under the FOCE Interaction estimation method (p<0.001 for the objective function with 2df). Individually, treatment groups were distinguishable with a covariate representing lorazepam treatment for the kappa (growth rate), gamma (time of maximum growth) and alpha (maximum tumor size) terms (p<0.001) individually. However, once multiple factors were added, the effect of treatment on the alpha term (i.e., the projected maximum size asymptote for the tumor) was greatest, and the effect on the other two terms were no longer significant. Specifically, the objective function changed from 1791.3 to 1728.8 with the addition of lorazepam treatment as a covariate on the alpha term. This represents a statistically significant change with p<0.0001 for 1 degree of freedom. In addition, the presence of lorazepam resulted in a predicted maximum tumor size approximately ½ as large as that predicted in the presence of vehicle (14900 vs 28400um3).

Once the tumor burden reached 2 cm, the mice were sacrificed 2 hours after the last dose of vehicle or lorazepam, and tumors were removed and processed for analysis. Tissue sections were stained for TSPO to determine if lorazepam treatment altered TSPO density (26, 27). Based on immunohistochemical analysis, we did not observe a significant difference in TSPO expression between the lorazepam treated and vehicle groups (data not shown). Lorazepam did have an effect on cell proliferation, as there is a significant decrease in expression of the proliferation-associated protein Ki67 in mice treated with lorazepam compared to the vehicle group (Figure 4B). Furthermore, lorazepam treatment did not affect vascularization, as the number of vessels per field is not significantly different between the two groups (Figure 4B). TUNEL analysis reveals that lorazepam has pro-apoptotic actions in vivo, with the lorazepam treated group having significantly more apoptotic cells compared to the vehicle group (Figure 4B).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to characterize TSPO expression in human prostate cancer samples and to determine its role as a potential therapeutic target for advanced disease. We have shown that TSPO expression is increased early in the neoplastic process, as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) has significantly increased levels of TSPO compared to normal prostate tissue and BPH. Moreover, we have demonstrated that TSPO expression increases with progression, as prostate cancer metastases have significantly more TSPO expression than all other tissues examined, including PIN and primary prostate cancer. Expression analysis in vitro suggests that TSPO is highly expressed in prostate cancer cell lines differing in their invasive abilities and androgen-sensitivity. Together our data support previous studies reporting that TSPO density is elevated in high-grade astrocytomas (11), glioblastomas (28), and highly aggressive breast cancer cell lines (29) compared to low-grade brain lesions and non-aggressive breast cancer cell lines. Similarly, Beinlich et al. reported that the TSPO ligand Ro5-4864 has the highest affinity binding capacity in highly aggressive, estrogen receptor (ER) negative, progesterone receptor (PR) negative breast cancer cell lines BT-20 and MDA-MB-435-5 but binds with low capacity in ER-positive, PR-positive nonaggressive MCF-7 and BT-474 breast cancer cell lines (30).

Several studies in the past decade have suggested that TSPO may play a role in carcinogenesis through its action as a modulator of cell proliferation. TSPO is highly expressed in steroidogenic cells, such as those of the testes and adrenals, of which TSPO ligands have been shown to regulate cell proliferation (31). TSPO ligands have also been shown to affect proliferation in various tumors, such as astrocytomas, breast, esophageal, and colorectal (11–14). For our studies, we utilized one of the most common TSPO ligands, PK11195, as well as the benzodiazepine lorazepam, which has not previously been considered a TSPO antagonist. We demonstrate that both PK11195 and lorazepam have anti-proliferative properties in prostate cancer cells in vitro. Because lorazepam is a clinically approved drug that could easily be translated from preclinical studies to the prostate cancer patient population, we wanted to determine if lorazepam also exhibits anti-proliferative actions in vivo. We observe a decrease in the length of time it took for the prostate cancer xenograft tumors to reach maximum size in the lorazepam treated mice compared to the vehicle group. Additionally, Ki67 expression, a protein marker for cell proliferation, is decreased in the lorazepam treated group compared to mice given vehicle only. In our tumor xenograft studies, the mice would become sedated for approximately 2 hrs post-injection with lorazepam but could still ambulate when stimulated and remained responsive during the entire time. There were no deaths associated with dosing once a day with lorazepam at 40 mg/kg for the entire study. The half-life of lorazepam in mice is 2 hours while in humans it is approximately 12 hours. The LD50 in mice for lorazepam is 3178 mg/kg (oral) and we have observed significant effects on induction of apoptosis at 40 mg/kg in mice. The concentration of lorazepam needed to induce apoptosis in tumor cells in patients would likely be achievable. This study further confirms that TSPO ligands modulate cell proliferation and provide continued evidence supporting the potential use of TSPO antagonists as anticancer drugs.

In all of our in vitro studies, PK11195 exhibited more potent anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects than lorazepam (Figure 2). This is likely due to the difference in binding affinity, as PK11195 binds TSPO at nanomolar concentrations (KD < 20nM) (32). Furthermore, it has been reported that lorazepam is significantly less potent than PK11195 at displacing various ligands from TSPO binding sites (20). However, lorazepam appears to have fewer off-target effects than PK11195 as the wildtype HEK293 cells with low TSPO expression had significant cell death with PK11195 but were minimally affected by lorazepam, while HEK293-TSPO overexpressing cells were susceptible to death by both compounds.

Although benzodiazepines have been used clinically for over 50 years, their application as a form of cancer therapy has not been explored. We have shown that lorazepam, a benzodiazepine commonly prescribed to treat anxiety disorders, inhibits prostate cancer cell growth and survival. TSPO expression is elevated as early as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and high expression continues in adenocarcinoma localized to the prostate while low TSPO levels are maintained in normal adjacent to tumor (NAT) and in benign disease (BPH). The in vitro experiments suggest that high TSPO levels confer susceptibility to antagonist-induced cell death and premalignant elevation of TSPO expression presents an opportunity for preventative treatment for prostate cancer. The immunohistochemical analyses of prostate tissue also demonstrated that the metastatic lesions had the highest TSPO levels and would suggest that benzodiazepine treatment for men with castrate-resistant disease may be a new potential therapeutic option. Lorazepam is currently administered most often at a dose range of 1-10 mg/day for anxiolytic effects. In patients treated for anxiety, the most frequent adverse reaction to lorazepam was sedation followed by dizziness, weakness, and unsteadiness (33), and benzodiazepine overdose in humans is uncommon except when taken with alcohol. We provide evidence that lorazepam has anti-tumor effects similar to those demonstrated by the well-known TSPO-specific antagonist, PK11195 and provide a potential treatment opportunity with minimal toxicity for use after failure of androgen-deprivation therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This publication was made possible by Grant Number 5 UL1 RR024153 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (BP, AP) and by Department of Defense Pre-Doctoral grant PC080062 (AF). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR, NIH or DoD. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp.

References

- 1.Anholt RR, Pedersen PL, De Souza EB, Snyder SH. The peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor. Localization to the mitochondrial outer membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:576–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papadopoulos V. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine/diazepam binding inhibitor receptor: biological role in steroidogenic cell function. Endocrine Reviews. 1993;14:222–40. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-2-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmel I, Fares FA, Leschiner S, Scherubl H, Weisinger G, Gavish M. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors in the regulation of proliferation of MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cell line. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1999;58:273–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batra S, Alenfall J. Characterization of peripheral benzodiazepine receptors in rat prostatic adenocarcinoma. Prostate. 1994;24:269–78. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990240509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz Y, Eitan A, Gavish M. Increase in peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites in colonic adenocarcinoma. Oncology. 1990;47:139–42. doi: 10.1159/000226806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz Y, Ben-Baruch G, Kloog Y, Menczer J, Gavish M. Increased density of peripheral benzodiazepine-binding sites in ovarian carcinomas as compared with benign ovarian tumours and normal ovaries. Clinical Science. 1990;78:155–8. doi: 10.1042/cs0780155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batra S, Iosif CS. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptor in human endometrium and endometrial carcinoma. Anticancer Research. 2000;20:463–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han Z, Slack RS, Li W, Papadopoulos V. Expression of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) in human tumors: relationship to breast, colorectal, and prostate tumor progression. Journal of Receptor & Signal Transduction Research. 2003;23:225–38. doi: 10.1081/rrs-120025210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner C, Grimm S. The permeability transition pore complex in cancer cell death. Oncogene. 2006;25:4744–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209609. erratum appears in Oncogene. 2006 Oct 26;25(50):6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch T, Decaudin D, Susin SA, et al. PK11195, a ligand of the mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor, facilitates the induction of apoptosis and reverses Bcl-2-mediated cytoprotection. Experimental Cell Research. 1998;241:426–34. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miettinen H, Kononen J, Haapasalo H, et al. Expression of peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor and diazepam binding inhibitor in human astrocytomas: relationship to cell proliferation. Cancer Research. 1995;55:2691–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papadopoulos V, Kapsis A, Li H, et al. Drug-induced inhibition of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor expression and cell proliferation in human breast cancer cells. Anticancer Research. 2000;20:2835–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutter AP, Maaser K, Hopfner M, Huether A, Schuppan D, Scherubl H. Cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Synergistic antiproliferative action with ligands of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor. Journal of Hepatology. 2005;43:808–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maaser K, Hopfner M, Jansen A, et al. Specific ligands of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human colorectal cancer cells. British Journal of Cancer. 2001;85:1771–80. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decaudin D, Castedo M, Nemati F, et al. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligands reverse apoptosis resistance of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Research. 2002;62:1388–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camins A, Diez-Fernandez C, Pujadas E, Camarasa J, Escubedo E. A new aspect of the antiproliferative action of peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor ligands. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;272:289–92. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00652-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braestrup C, Squires RF. Specific benzodiazepine receptors in rat brain characterized by high-affinity (3H)diazepam binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1977;74:3805–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JK, Morgan JI, Spector S. Benzodiazepines that bind at peripheral sites inhibit cell proliferation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:753–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JK, Taniguchi T, Spector S. Structural requirements for the binding of benzodiazepines to their peripheral-type sites. Molecular Pharmacology. 1984;25:349–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park CH, Carboni E, Wood PL, Gee KW. Characterization of peripheral benzodiazepine type sites in a cultured murine BV-2 microglial cell line. GLIA. 1996;16:65–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199601)16:1<65::AID-GLIA7>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alenfall J, Batra S. Modulation of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor density by testosterone in Dunning G prostatic adenocarcinoma. Life Sciences. 1995;56:1897–902. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz Y, Amiri Z, Weizman A, Gavish M. Identification and distribution of peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites in male rat genital tract. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1990;40:817–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90321-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Bokhoven A, Varella-Garcia M, Korch C, Hessels D, Miller GJ. Widely used prostate carcinoma cell lines share common origins. The Prostate. 2001;47:38–51. doi: 10.1002/pros.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delavoie F, Li H, Hardwick M, et al. In vivo and in vitro peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor polymerization: functional significance in drug ligand and cholesterol binding. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4506–19. doi: 10.1021/bi0267487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeliseev AA, Kaplan S. TspO of rhodobacter sphaeroides. A structural and functional model for the mammalian peripheral benzodiazepine receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:5657–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calvo DJ, Medina JH. Regulation of peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors following repeated benzodiazepine administration. Functional Neurology. 1992;7:227–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller LG, Greenblatt DJ, Barnhill JG, Shader RI. Chronic benzodiazepine administration. I. Tolerance is associated with benzodiazepine receptor downregulation and decreased gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor function. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 1988;246:170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cornu P, Benavides J, Scatton B, Hauw JJ, Philippon J. Increase in omega 3 (peripheral- type benzodiazepine) binding site densities in different types of human brain tumours. A quantitative autoradiography study. Acta Neurochirurgica. 1992;119:146–52. doi: 10.1007/BF01541799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardwick M, Fertikh D, Culty M, Li H, Vidic B, Papadopoulos V. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) in human breast cancer: correlation of breast cancer cell aggressive phenotype with PBR expression, nuclear localization, and PBR-mediated cell proliferation and nuclear transport of cholesterol. Cancer Research. 1999;59:831–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beinlich A, Strohmeier R, Kaufmann M, Kuhl H. Specific binding of benzodiazepines to human breast cancer cell lines. Life Sciences. 1999;65:2099–108. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garnier M, Dimchev AB, Boujrad N, Price JM, Musto NA, Papadopoulos V. In vitro reconstitution of a functional peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor from mouse Leydig tumor cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994;45:201–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Fur G, Vaucher N, Perrier ML, et al. Differentiation between two ligands for peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites, [3H]RO5-4864 and [3H]PK 11195, by thermodynamic studies. Life Sciences. 1983;33:449–57. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohn JB, Wilcox CS. Long term comparison of alprazolam, lorazepam and placebo in patients with an anxiety disorder. Pharmacotherapy. 1984;2:93–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1984.tb03327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]