Abstract

Background

Sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss is an acute dysfunction of the inner ear whose cause cannot be determined with the currently available methods of clinical diagnosis.

Methods

This continuous medical education article is based on a selective review of the literature and on the revised S2 guidelines for acute sensorineural hearing loss of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF), which were issued on 28 January 2009.

Results

Recent surveys in Germany suggest that the incidence of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss may be as high as 300 per 100 000 persons per year. To distinguish this entity from acute hearing loss of other causes, special tests are necessary, including ear microscopy, pure-tone audiometry, and acoustic evoked response audiometry. No clinical trial of the highest evidence level has yet been published to document the efficacy of any type of treatment for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Nonetheless, there is evidence from trials with lower levels of evidence, post-hoc analyses, and assessments of secondary endpoints of clinical trials indicating that plasma-expander therapy, the systemic and local (intratympanic) administration of cortisone, and the reduction of acutely elevated plasma fibrinogen levels may be beneficial.

Conclusion

Further clinical trials are needed to validate these preliminary results. Until clear data are available, the predicted benefit and risk of any proposed treatment for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss should be discussed in detail with the patient before the treatment is begun.

Keywords: sudden idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, treatment, hearing damage, guideline

Sudden hearing loss usually arises unilaterally and reflects acute dysfunction of the inner ear. Tinnitus is simultaneously present in about 85% of cases, and vertigo of a peripheral vestibular type in up to 30%. Unilateral hearing loss impairs the localization of sound, the comprehension of spoken language in a noisy environment, and the enjoyment of music. These primary symptoms are often accompanied by oversensitivity to noise and by a pressure sensation in the affected ear. Secondary symptoms may ensue, such as anxiety, inadequate coping with illness, various types of psychosomatic disturbance, and, finally, an impaired quality of life.

The learning aims of this article for the reader are

to understand the pathophysiological considerations relating to sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss,

to become acquainted with the localizing diagnosis of hearing disorders and the diagnostic tests used for it,

and to know the usual treatments for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss and the state of the evidence for their effectiveness.

Methods

The literature was selectively searched for this article. The results discussed here are based on the updated version of the S2 guideline entitled “Hörsturz” (sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss), issued by the Working Group of the Scientific Medical Specialty Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF). Levels of evidence were graded according to the Oxford scheme. The latest update is that of 28 January 2009. The German Society for Otorhinolaryngology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde) is expected to grant authorization for online publication (AWMF online) in November 2009. Review articles in the Cochrane Library on acute, idiopathic hearing loss due to inner ear disturbances were also taken into account. In view of the limited space available for this article, the author provides only selected references to the literature on the disorder (which is very extensive), and has chosen the particular topics to be discussed on the basis of his own subjective judgment and clinical experience.

Definition.

Sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss reflects acute dysfunction of the inner ear. Its main symptom is sudden, usually unilateral hearing loss.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology.

Epidemiological studies in Germany indicate an incidence of up to 300 cases per 100 000 persons per year.

Every human being depends on information and communication, both at home and at work, and a hearing disturbance is thus a significant impairment. More and more patients with acute hearing disturbances consult otorhinolaryngologists. A recent epidemiological study in Germany indicates an incidence as high as 300 per 100 000 persons per year (1, 2); it follows that more than 200 000 persons have sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss in Germany each year. Women and men are about equally affected. The peak age-related incidence is between the ages of 50 and 60.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The etiology and pathogenesis of this problem are unclear, which is why it is referred to as acute, idiopathic hearing loss originating from the inner ear. Acute inner ear dysfunction of known cause is, by definition, excluded from the syndrome under discussion. Acute acoustic trauma resulting from a loud noise is thus a different disorder, even though its clinical manifestations and course may be identical.

The inner ear is only 3 to 4 mm in size; it is embedded in solid bone, the petrous portion of the temporal bone. Currently available methods of clinical diagnosis are inadequate to reveal the cause of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Experimental and epidemiological studies, as well as pathophysiological considerations, suggest that this syndrome can be induced by multiple different processes. The potential causes that are most commonly postulated are listed in Box 1.

Box 1. Postulated causes of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss *1.

Hypoperfusion (microemboli, venous stasis, vascular dysregulation)

Infection (e.g., by neurotropic viruses)

Immunological processes (e.g., autoantibodies)

Ion channel disturbances (e.g., endolymphatic hydrops)

Hereditary causes

*1 consensus conference on the guideline for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss, 28 January 2009

Uncertain cause.

The etiology and pathogenesis of this problem are unclear, which is why it is referred to as an acute, idiopathic hearing loss originating from the inner ear.

Multiple pathophysiological mechanisms cause damage to the inner ear producing similar clinical manifestations and course. Inner ear damage has been well studied experimentally with the paradigm of acoustically induced inner-ear hearing loss. Inner ear damage causes increased secretion of the neurotransmitter glutamate (3) in the synapse between the inner hair cell and the first neuron of the auditory pathway. The first consequence of this may be a loss of synapses between the inner hair cell and the afferent neuron. This impairs mechano-electrical transduction, i.e., the conversion of the acoustic stimulus into a neural signal. The result is hearing loss. The affected frequencies and the extent of hearing loss are a function of the number and location of the hair cells that are lost. Hearing loss of this type is, in principle, reversible, especially when the mechanism of injury (e.g., regional hypoperfusion) can be eliminated. On the other hand, persistent hair cell dysfunction can also lead to persistently excessive glutamate secretion into the synaptic cleft that leads to the afferent neuron. In consequence, the cytoplasmic and intramitochondrial Ca2+ concentration in the afferent neuron rises, whereupon the mitochondria depolarize, and apoptosis ensues. Activated proteases also damage the afferent neuron (4).

A vascular cause for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss has long been presumed because of its abrupt clinical course and the accompanying circumstances. As early as 1887, Politzer gave one of the first detailed descriptions of this disorder, calling it “angioneurotische Oktavuskrise” (angioneurotic eighth-nerve crisis) (5). Many clinical-scientific studies have provided evidence for regional hyperperfusion of the cochlea as a cause. Lin et al. (6), for example, recently found that a group of 1423 patients with sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss had a risk of stroke in the ensuing five years that was 1.64 times as high as that of a control group. It follows that patients with sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss should have a general medical and neurological examination, so that potential vascular risk factors can be recognized early and treated if necessary.

Although all these pathophysiological considerations suggest that sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss should be treated as soon as possible after it arises, the need for urgent treatment has not been documented by clinical data. Thus, sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss is no longer considered a therapeutic emergency or a disorder that must be rapidly treated.

Clinical aspects of sudden, unilateral hearing loss

In both inpatient and outpatient settings, physicians are often confronted with the problem of sudden, unilateral hearing loss. This is not necessarily to be equated with sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss, as the list of differential diagnoses is long. All of the essential tests for the diagnosis of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss are listed in Box 2, and the differential diagnoses are listed in Box 3.

Box 2. Necessary tests when sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss is suspected *1.

Otorhinolaryngological examination

Ear microscopy

Auditory testing (tuning fork, tone audiogram)

Tympanometry

Measurement of otoacoustic emissions (OAE) or two recruitment tests

Acoustic evoked potentials (6 weeks after the acute episode of hearing loss)

Vestibular nerve testing

Blood pressure measurement

*1 consensus conference on the guideline for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss, 28 January 2009

Box 3. Differential diagnoses of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss*1.

Viral infection (e.g., adenoviruses, herpes zoster, mumps, HIV)

Multiple sclerosis

Autoimmune vasculitis (e.g., Cogan syndrome)

Intoxication (e.g., medications, illicit drugs, industrial poisons)

Dialysis-dependent renal failure

Tumors (e.g., acoustic neuroma, tumors of the brainstem and petrous bone)

Perilymph fistula (internal and external)

Barotrauma

Acute acoustic trauma

Cervical spine disorders (e.g., trauma, postural deformity)

Bacterial labyrinthitis (e.g. otitis media, syphilis, borreliosis)

CSF loss syndrome (e.g., after lumbar puncture)

Meningitis

Hereditary (genetic) deafness originating in the inner ear

Genetic syndromes (e.g., Usher syndrome, Pendred syndrome)

Hematological diseases (e.g., polycythemia, leukemia, dehydration, sickle-cell anemia)

Psychogenic auditory disturbances

Tubal ventilation disorder

*1 modified in accordance with the consensus conference on the guidline for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss, 28 January 2009

Higher risk of stroke.

A study has shown that patients with sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss have a risk of stroke in the next five years that is 1.64 times higher than that of persons in the control group.

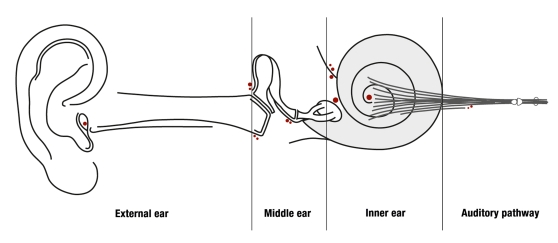

When taking the patient’s history and performing the physical examination, it is best for the physician to use the anatomy of the ear as an orienting guide. The ear is divided into the external ear, the middle ear, the inner ear, and the auditory pathway (figure).

Figure.

Schematic diagram of the external, middle, and inner ear and the auditory pathway

No need for urgent treatment.

Clinical data do not document the need for urgent treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss.

Sudden hearing loss originating in the external ear is usually due to blockage of the external auditory canal. This may be of infectious origin (otitis externa) or simply a result of obstruction of the canal by earwax (cerumen) or a foreign body. In such cases, ear microscopy establishes the diagnosis clearly and reliably. If the canal is not blocked, processes in the middle ear should be considered next. Fluid in the middle ear (so-called sero- or mucotympanon) very often impairs sound conduction in children and can do so in adults as well in the aftermath of rhinitis. By measuring the pressure and volume in the external auditory canal (tympanometry), the examiner can determine the capacity of the eardrum to vibrate and thereby establish the diagnosis. If there is an effusion in the middle ear and the patient has severe pain, the diagnosis is acute otitis media. Sometimes, a lack of ventilation of the middle ear with low pressure will alone suffice to impair the patient’s hearing, even if there is no effusion. A tubal ventilation disturbance of this type is often hard to distinguish from sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. These middle ear disorders can usually be diagnosed without difficulty by an experienced examiner using ear microscopy. Disturbances of sound conduction in the external and middle ear (so-called conductive hearing loss) can be simply tested for with the Rinne and Weber tuning-fork maneuvers, but these are not reliable in themselves, as only a single frequency (448 Hz) is tested. One must also use pure tone audiometry to determine the auditory threshold over a wider range of frequencies (from 250 Hz to 8 kHz). In this test, tones are played through a headset either into the patient’s ears (air conduction) or onto the bone. If the tones are heard less well by air conduction, but normally by bone conduction, then the patient is suffering from conductive hearing loss. The cause must be sought in the middle or external ear.

Topological pathology.

Clinical history-taking based on the anatomy of the ear leads the way to the diagnosis.

On the other hand, if the tones are heard equally poorly regardless of whether they are conducted through air or through bone, then sensorineural hearing loss is present. The responsible pathology must then be sought in the cochlea. This type of hearing loss originating in the inner ear is characteristic of the disorder under discussion (sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss). It can be further characterized as high-, low-, or intermediate-frequency hearing loss, if a particular range of frequencies is affected, or else as pancochlear hearing loss if all frequencies are affected. If pancochlear hearing loss is present and so severe that the patient can no longer understand speech, then the patient is said to be deaf in the affected ear. Sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss is the most common type of acute hearing loss originating in the inner ear; a cause can be identified only in a small minority of cases. The potential causes include acoustic trauma, ototoxic medications, toxic inner-ear hearing loss secondary to otitis media, barotrauma, infection, and others.

Clinical aspects.

Sudden hearing loss originating in the external ear is usually due to blockage of the external auditory canal.

Sensorineural hearing loss due to a disturbance of the auditory pathway is very rare. One possible cause, for example, is acoustic neuroma, which is actually a schwannoma of the vestibular nerve that also compresses the auditory nerve as it grows. Other diseases, such as multiple sclerosis or ischemic stroke, can affect the auditory pathway. The tone audiogram usually shows sensorineural hearing loss. The patient’s ability to understand speech is markedly worse than the tone audiogram would lead one to expect if the hearing loss were due to inner ear dysfunction. A characteristic finding in hearing loss originating in the inner ear is a rapid rise of loudness perception in the affected range of frequencies, so that loud tones are perceived as equally loud in the normal and abnormal ears. This so-called recruitment is absent in hearing loss originating in the auditory pathway. Special suprathreshold hearing tests are now only rarely used to demonstrate retrocochlear hearing loss, as this can now be unequivocally demonstrated with the aid of auditory evoked potentials (AEP), particularly when the otoacoustic emissions generated by the inner ear are intact.

The treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss

A wide variety of medications and other treatments are currently used for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Box 4 gives an overview of the more common ones. The many clinical trials performed on this subject to date are of variable quality; none unequivocally document the effectiveness of any medication or combination of medications. The best are roughly comparable to phase II clinical trials. There has been as yet no clinical study conforming to Good Clinical Practice that has demonstrated as a primary endpoint, with statistical significance and in an adequate number of cases, the superiority of any type of treatment over any other type of treatment, or over placebo. Significant differences do appear, however, in secondary endpoints, subgroup analyses, and post hoc analyses. Trials of this nature provide initial evidence for effective modes of treatment. No company or independently financed research group has yet performed a phase III therapeutic trial for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Thus, none of the highly diverse treatments currently used for this disorder have been shown to be either effective or ineffective.

Box 4. Common treatments of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss*1.

Rheological agents

Glucocorticoids

Reduction of endolymph volume

Antioxidants

Platelet aggregation inhibitors

Fibrinogen reduction by apheresis

Hyperbaric oxygenation

*1 consensus conference on the guideline for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss, 28 January 2009

Proof of efficacy.

No studies are yet available that unequivocally document the efficacy of medications for the treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss.

For this reason, the German Association of Otorhinolaryngologists (Deutscher Berufsverband der Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Fachärzte), with the support of the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung), currently directs that the treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss is to be billed as an individual, rather than insurance-covered, service. It is not clear whether this situation will remain unchanged, or whether this development might even be extended to other types of treatment that have not been shown to be effective at the highest level of evidence.

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids.

In Germany, glucocorticoids have not been approved for the treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss.

Glucocorticoids are considered around the world to be the gold standard of treatment for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss, because it is thought the disorder might be due to an infectious/inflammatory or autoimmune process. The data, however, are inconsistent. Hardly any of the more than 20 clinical trials published to date meet the quality requirements of the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). Furthermore, their results with respect to steroid efficacy are divergent. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that a current meta-analysis (7) concludes there is no evidence that glucocorticoids are better than placebo in the treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Despite this, the disorder is usually treated with prednisolone or dexamethasone. The recommended dosages are highly variable, ranging from 1 to 10 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. Glucocorticoids have not been approved in Germany for the treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Their use for this indication in Germany is off-label.

Plasma expanders

Plasma expanders (so-called infusion therapy) are more commonly used in the German-speaking countries than elsewhere. They raise the cardiac output and improve the microcirculation. They are considered to be of potential therapeutic benefit in acute inner ear hearing loss due to ischemia. The use of a new type of hydroxyethyl starch solution has been studied in a clinical trial with 210 patients (8). Three different doses were tested against placebo. This was a classic phase II trial for dose-finding and determination of efficacy. The treatment, however, was found not to have any significantly different effect than a placebo, with respect to either the primary endpoint (hearing gained in a tone audiogram one week later) or the secondary endpoints. Post-hoc analysis suggests possible efficacy in patients with sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss who also have hypertension, and in those who began treatment more than 48 hours after the onset of hearing loss. Even if these subgroup analyses make clinical sense, efficacy still has not been demonstrated in a comprehensive phase III trial. In other countries around the world, plasma expanders play a rather minor role in the treatment of this disorder. Different types of hydroxyethyl starch solution are used; in Germany, some of them have been approved for the indication “ischemic disease of the inner ear.”

Fibrinogen reduction

The blood coagulation system plays an important role both as a vascular risk factor and as a therapeutic target in the treatment of myocardial infarction and stroke. As clot lysis has a relatively high risk of complications, there is now more clinical interest in fibrinogen reduction as a treatment for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Batroxobin, a fibrinogen-reducing drug, was found to be significantly more effective than glucocorticoids in a clinical trial involving 162 patients (9), yet the difference could not be confirmed when it was evaluated a second time (10). In another trial, heparin-induced, extracorporeal LDL precipitation (HELP) apheresis was used for fibrinogen reduction and was found to be more effective than glucocorticoids and plasma expanders (11), but the significant differences were found only in secondary endpoints and in fibrinogen-dependent post hoc analyses. Nor has there yet been any comprehensive phase III trial to confirm the suggestive trial results for either batroxobin or HELP apheresis.

Local therapy

Local application.

Vestibulotoxic aminoglycosides have long been instilled into the middle ear through the tympanic membrane as an alternative treatment for Ménière’s disease.

Vestibulotoxic aminoglycosides have long been instilled into the middle ear through the tympanic membrane as an alternative treatment for Ménière’s disease. In the future, the local application of medications may become an interesting alternative to the systemic treatments now used for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Puncturing the tympanic membrane under local anesthesia is nearly painless. Local complications, such as a persistent tympanic perforation or transient dizziness, can occur. The intratympanic instillation of medications through the eardrum into the middle ear has the advantage of yielding a high concentration of the active substance in the inner ear. Thus, only a small amount of medication need be given, systemic resorption is kept to a minimum, and there are hardly any systemic side effects. Clinical trials to date have mostly involved the instillation of glucocorticoids after conventional treatment has failed (12– 14). Although the data are not yet fully clear, intratympanic glucocorticoid instillation can now be considered a type of therapy to be held in reserve in case the conventional treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss fails.

Research needed.

The treatments that have been used to date still need to be evaluated in industry-independent research studies.

The otorhinolaryngologist treating sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss is in a difficult position. There have been many clinical trials of diverse types of therapy, but none of them provide level 1 evidence, because of inadequate case numbers, endpoints, or study performance (15– 17). As this disorder is relatively mild, and its incidence in earlier estimates was fairly low (5 to 20 cases per 100 000 persons per year [18]), the pharmaceutical industry has shown little interest in it to date, for economic reasons. This situation may change, as the incidence is now reported to be considerably higher (1, 2). Industry-independent research support for large clinical trials has only become available in Germany in the last few years through the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft). Sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss is in the same situation as many other rare diseases: it has, in fact, been recognized as an “orphan disease” by both the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) and the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This means that the treating physician must carefully weigh the risks and benefits of treating this disorder. Side effects, if they arise at all, should be very rare and very mild (21). Moreover, patients should be informed at length about the treatment to be provided, and their informed consent should be documented in writing.

Further Information On Cme.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education.

Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquired only through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire within 6 weeks of publication of the article, i.e., by 20 November 2009. See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de.

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit „uniform CME number“ (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under „meine Daten“ („my data“), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

The solutions to the following questions will be published in Issue 49/2009. The CME unit “The Medical and Surgical Treatment of Glaucoma” (Issue 37/2009) can be accessed until 23 October 2009.

For Issue 45/2009, we plan to offer the topic „Principles of Pediatric Emergency Care.“

Solutions to the CME questionnaire in Issue 33/2009:

Koletzko S, Osterrieder S: Acute Infectious Diarrhea in Children.

Solutions: 1b, 2d, 3b, 4e, 5b, 6c, 7b, 8e, 9c, 10a

Please answer the following questions to participate in our certified Continuing Medical Education program. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which of the following is a primary manifestation of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss?

Blast trauma

Acute inner ear dysfunction

Acoustic trauma

Inadequate disease coping

Cerumen

Question 2

Persons of what age are most commonly affected by sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss?

Under age 29

Age 30 to 39

Age 40 to 49

Age 50 to 60

Over age 70

Question 3

Which diagnostic techniques provide an unequivocal diagnosis of hearing loss due to inner ear dysfunction?

Acoustic evoked potentials (AEP) + tone audiometry

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography + EEG

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) + ear microscopy

Computerized tomography (CT) + vestibular testing

Positron-emission tomography (PET) + x-ray

Question 4

What treatment is usually given for sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss in the German-speaking countries?

Antihistamine bolus

Infusion therapy with plasma expanders

Infusion therapy with diclofenac

Infusion therapy with sedatives

Antihypertensive agent bolus

Question 5

Which disease of the external ear often causes sudden hearing loss and pain?

Apostasis otum

Basal-cell carcinoma of the antitragus

Otitis externa

Otosclerosis

Acoustic neuroma

Question 6

According to the recommendation of the German Society for Otorhinolaryngology, within what period of time should sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss be treated?

The time to treatment is not important (not an emergency, does not require rapid treatment)

Within 3 hours (emergency)

Within 6 hours (emergency)

Within 24 hours (needs rapid treatment)

Within 3 days (needs rapid treatment)

Question 7

What medication has been definitively shown in clinical trials to be an effective treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss?

Prednisolone

Hydroxyethyl starch solution

Pentoxifylline

Gingko biloba

None

Question 8

For what disease have patients with sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss been shown to have an elevated risk?

Stroke

Myocardial infarction

Retinal infarction

Renal infarction

Intestinal infarction

Question 9

What is the advantage of the local administration of medications in the middle ear?

The instillation is painless.

The organ of balance cannot be affected.

The concentration of active substance in the inner ear is higher.

The amount of active substance is higher.

Effectiveness has been demonstrated in clinical trials.

Question 10

A number of clinical trials on the treatment of sudden, idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss have been published to date. Which of the following best characterizes the highest-quality trials now available?

Phase I clinical trials

Phase II clinical trials

Phase III clinical trials

Phase IV clinical trials

Phase V clinical trials

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The author serves as a consultant for the B. Braun Avitum AG company and has received lecture honoraria from Fresenius Kabi Deutschland AG.

References

- 1.Klemm E, Deutscher A, Mösges R. A Present Investigation of the Epidemiology in Idiopathic Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Laryngorhinootologie. 2009;88(8):524–527. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1128133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olzowy B, Osterkorn D, Suckfüll M. The incidence of sudden hearing loss is greater than previously assumed. MMW Fortschr Med. 2005;147(14):37–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puel JL, Ruel J, d’Aldin Gervais C, Pujol R. Excitotoxicity and repair of cochlear synapses after noise-trauma induced hearing loss. Neuroreport. 1998;9:2109–2114. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806220-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu BH, Henderson D, Nicotera TM. Involvement of apoptosis in progression of cochlear lesion following exposure to intense noise. Hear Res. 2002;166:62–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Politzer A. Lehrbuch der Ohrenheilkunde für practische Ärzte und Studierende. 1887 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin HC, Chao PZ, Lee HC. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss increases the risk of stroke: a 5-year follow-up study. Stroke. 2008;39(10):2744–2748. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.519090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlin AE, Parnes LS. Treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: II. A Meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(6):582–586. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klemm E, Bepperling F, Burschka AM, Mösges R and study group. Hemodilution therapy with hydroxyethyl starch solution (130/0.4) in unilateral idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: A dose-Finding, double-blind, placebo-controlled, international multi-center trial with 210 patients. Otology & Neurotology. 2007;28:157–170. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000231502.54157.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubo T, Matsunaga T, Asai H, Kawamoto K, Kusakari J, Nomura Y, Oda M, Yanagita N, Niwa H, Uemura T, et al. Efficacy of defibrin ogenation and steroid therapies on sudden deafness. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:649–652. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860180063031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiraishi T, Kubo T, Okumura S, Naramura H, Nishimura M, Okusa M, Matsunaga T. Hearing recovery in sudden deafness patients using a modified defibrinogenation therapy. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;501:46–50. doi: 10.3109/00016489309126213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suckfüll M Hearing Loss Study Group. Fibrinogen and LDL apheresis in treatment of sudden hearing loss: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1811–1817. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11768-5. Erratum in: Lancet 2002; 361: 1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battaglia A, Burchette R, Cueva R. Combination therapy (intratympanic dexamethasone + high-dose prednisone taper) for the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29(4):453–460. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318168da7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho HG, Lin HC, Shu MT, Yang CC, Tsai HT. Effectiveness of intratympanic dexamethasone injection in sudden-deafness patients as salvage treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(7):1184–1189. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plontke SK, Löwenheim H, Mertens J, et al. Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial on the safety and efficacy of continuous intratympanic dexamethasone delivered via a round window catheter for severe to profound sudden idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss after failure of systemic therapy. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(2):359–369. doi: 10.1002/lary.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett MH, Kertesz T, Yeung P. Hyperbaric oxygen for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss and tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;24(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004739.pub3. CD004739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei BP, Mubiru S, O’Leary S. Steroids for idiopathic sudden sensori-neural hearing loss. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;25(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003998.pub2. CD003998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong Y, Liang C, Li J, Tian A, Chen N. Vasodilators for sudden sensori neural hearing loss: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi. 2002;37(1):64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klemm E, Schaarschmidt W. Epidemiologische Erhebungen zu Hörsturz, Vestibularisstörungen und Morbus Meniere. HNO-Prax. 1989;14:295–299. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakashima T, Itoh A, Misawa H, Ohno Y. Clinicoepidemiologic features of sudden deafness diagnosed and treated at university hospitals in Japan. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:593–597. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.109486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byl FM. Seventy-six cases of presumed sudden hearing loss occuring in 1973; prognosis and incidence. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:817–820. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540870515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García-Berrocal JR, Ramírez-Camacho R, Lobo D, Trinidad A, Verdaguer JM. Adverse effects of glucocorticoid therapy for inner ear disorders. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2008;70(4):271–274. doi: 10.1159/000134381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desloovere C, Knecht R. Infusion therapy in sudden deafness. Reducing the risk of pruritus after hydroxyethyl starch and maintaining therapeutic success—a prospective randomized study. Laryngorhinootologie. 1995;74(8):468–472. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-997783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]