Abstract

A fundamental organizing principle of auditory brain circuits is tonotopy, the orderly representation of the sound frequency to which neurons are most sensitive. Tonotopy arises from the coding of frequency along the cochlea and the topographic organization of auditory pathways. The mechanisms that underlie the establishment of tonotopy are poorly understood. In auditory brainstem pathways, topographic precision is present at very early stages in development, which may suggest that synaptic reorganization contributes little to the construction of precise tonotopic maps. Accumulating evidence from several brainstem nuclei, however, is now changing this view by demonstrating that developing auditory brainstem circuits undergo a marked degree of refinement on both a subcellular and circuit level.

Increasing the topographic organization of synaptic connections via activity-dependent refinement is a major milestone in the maturation of neuronal circuits1. In the developing auditory system, experience-dependent refinement of tonotopic maps has been well demonstrated in the auditory cortex and in multimodal-integration brain areas2-5. In contrast, primary auditory circuits in the brainstem are assembled with high topographic (tonotopic) precision early in development and show little evidence of subsequent refinement. This picture is based on a wealth of anatomical tracing studies in both birds and mammals that have shown that growing axons innervate their topographically correct target areas from the outset and do not establish aberrant, transient connections to incorrect nuclei6-9. Likewise, physiological studies indicate that a precise tonotopic organization is present as soon as central auditory pathways can be activated by sound10-12. Even if the formation of a projection is induced by embryonic otocyst (an ectodermal invagination that constitutes the primordium of the internal ear) removal, the projection is tonotopically organized13.

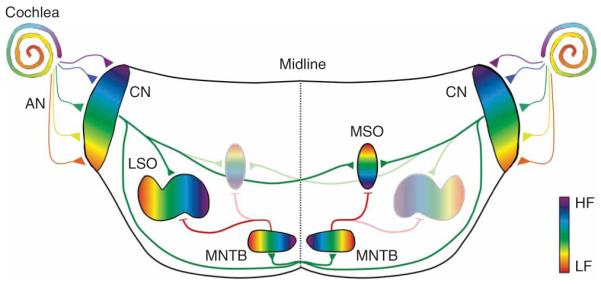

Recently, however, this traditional picture of a developmentally predetermined and ‘hard-wired’ auditory brainstem has undergone a substantial revision. It is becoming increasingly apparent that auditory synapses in the brainstem can express activity-dependent synaptic plasticity14-16 and that auditory brainstem circuits undergo an unexpected degree of synaptic reorganization. Here we summarize recent evidence from the cochlear nucleus and primary sound localization circuits (Fig. 1) that support the view that the emergence of precise tonotopy depends on circuit refinement, and discuss potential underlying mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of primary auditory sound localization circuits in the mammalian brainstem. For clarity, only the LSO or MSO are shown on each side. Except for the auditory nerve, excitatory connections are shown in green and inhibitory connections are shown in red. AN, auditory nerve; CN, cochlear nucleus; HF, high frequency; LF, low frequency.

Auditory nerve projections to the cochlear nucleus

Cochlear hair cells, the sensory cells that transform sound energy into electrical signals, are connected to the brain by spiral ganglion neurons whose centrally directed axons form the auditory nerve. After entering the brain, each auditory nerve fiber branches to innervate the three subdivisions of the cochlear nucleus complex: the anteroventral (AVCN), posteroventral (PVCN) and dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN). Each of these subdivisions is tonotopically organized, with DCN regions being innervated by auditory nerve fibers that arise from apical parts of the cochlea, tuned to high sound frequencies, and ventral cochlear nucleus regions being innervated by auditory nerve fibers arising from the basal (low frequency) part of the cochlea (Fig. 1). In the developing cochlear nucleus of both mammals and birds, this tonotopic (or cochleotopic) organization is present long before activity in the auditory nerve can be driven by sound stimuli and even before the onset of synaptic activity17,18. This indicates that the cochleotopic organization in the cochlear nucleus is set up by molecular guidance cues that probably include tyrosine kinase receptors and members of the ephrin receptor family19-21.

It has been difficult to demonstrate that these early cochleotopic maps are further sharpened by pruning of auditory nerve branches, although it has been known for 25 years that functional synapse elimination and axonal pruning takes place in the nucleus magnocellularis, the avian analog of the ventral cochlear nucleus22. In mature animals, nucleus magnocellularis neurons are innervated by only one or two auditory nerve fibers, which form large and powerful synaptic terminals, the endbulbs of Held, onto the soma of nucleus magnocellularis neurons. This distinct innervation pattern emerges gradually between embryonic day 12 (E12) and E17 by the pruning of auditory nerve fiber branches and the retraction of transient nucleus magnocellularis dendrites23. Electrophysiological studies have shown that endbulb synapse elimination is preceded by synaptic weakening and a decrease in the AMPA receptor-mediated quantal size24. Conversely, maintained endbulb inputs become stronger by an increase in AMPA receptor-mediated quantal size and the addition of synaptic release sites24,25. The molecular signals or synaptic activity patterns that initiate and maintain weakening or strengthening of endbulbs await further investigation. It is also unknown whether endbulb elimination actually increases the precision of the cochleotopic map, as the frequency tuning of converging fibers is unknown6.

Instead, the strongest evidence for refinement of the cochleotopic map in the cochlear nucleus is provided by recent anatomical tracing studies in which small clusters of neighboring spiral ganglion cells were labeled in embryonic and neonatal cats26 (Fig. 2). In late embryonic cats, tonotopically similar auditory nerve fibers terminate in well-defined ‘isofrequency bands’ in all three cochlear nucleus subdivisions. With development, the width of these isofrequency bands increases, as does the size of the cochlear nucleus subdivisions. However, the expansion of isofrequency bands and cochlear nucleus areas was disproportional, as the cochlear nucleus expanded more than the isofrequency bands. As a consequence, the relative width of termination bands decreased, resulting in an increase of the resolution of the cochleotopic map. This refinement was completed by postnatal day 6 (P6), after which termination bands and cochlear nucleus areas expanded at the same rates27. Because the peripheral auditory system in cats is still very immature during the first postnatal week and is not capable of supporting hearing at physiological sound levels28, this cochleotopic sharpening does not depend on auditory experience. Before hearing onset, however, the auditory nerve discharges in the form of burst-like activity patterns29,30; these burst-like activity patterns may guide refinement before hearing onset, analogous to the function of spontaneous retinal ganglion cell bursts for the refinement of thalamic circuits1,31 (see below).

Figure 2.

Cochleotopic refinement of auditory nerve projections in the developing anteroventral cochlear nucleus in neonatal cats. (a) In adult cats, labeling of a population of neighboring spiral ganglion cells (SG) in the cochlea gives rise to a frequency-specific termination band (blue) in the AVCN that runs perpendicular to the tonotopic axis (arrow). (b) In late embryonic and newborn kittens, a frequency-specific termination band is also present. Because cats are still deaf at this age, the emergence of precise topography between the cochlea and the AVCN is established without auditory experience. In newborn kittens, however, the observed width of this termination band (blue) is larger than the expected width (pink) predicted from normalizing termination band size to AVCN size at this age. This indicates that cochleotopic precision increases during development. (c) Population data indicate that isofrequency bands in kittens are about 50% wider than expected, suggesting that auditory nerve termination patterns are tonopically refined. Data are adapted from ref. 26. NS, not significant.

Synaptic reorganization in sound localization circuits

The major acoustic cues for determining the horizontal direction of incoming sound are interaural sound level differences (ILDs) and interaural time differences (ITDs). The primary binaural nuclei specialized to extract ILDs and ITDs are the lateral superior olive (LSO) and the medial superior olive (MSO), respectively. Similar to the cochlear nucleus, afferent pathways to these nuclei are topographically organized from the earliest stages on8,32 (Fig. 1). In contrast to the cochlear nucleus, however, the developing LSO and MSO show a remarkable degree of synaptic reorganization, a fact that may reflect the challenge of tonotopically aligning the inputs from both cochleae.

Synaptic refinement of a topographic inhibitory map in the lateral superior olive

Neurons in the LSO encode ILDs by integrating excitatory (glutamatergic) inputs from the ipsilateral cochlear nucleus with inhibitory (glycinergic) inputs from the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), which, in turn, is driven by sound at the contralateral ear33 (Fig. 1). Both inputs are tonotopically organized and are precisely aligned so that single LSO neurons are excited and inhibited by the same sound frequency. During development, this alignment is accomplished to a large degree without auditory experience because excitatory and inhibitory frequency tuning curves of most LSO neurons in gerbils are already matched at hearing onset (P13-14)34. At this age, however, inhibition from the contralateral ear is more effective (that is, has lower thresholds) than in adult animals, and excitatory and inhibitory best frequencies of individual LSO neurons are less precisely matched than in adults. Immaturity of cochlear mechanisms cannot fully account for these differences because an adult-like alignment is present in at least some neurons. Instead, it is likely that reorganization of central pathways contributes to the maturation of binaural responses in LSO neurons. This idea is supported by the pruning of MNTB axon terminals in the LSO and a decrease in the spread of LSO dendrites along the tonotopic axis32,35,36 (Fig. 3a). This pruning occurs after hearing onset and depends on auditory experience, as cochlear ablation interferes with the pruning process and with the maintenance of a pruned state37,38. In contrast with axonal pruning, on a function level, topographic sharpening of the MNTB-LSO pathway via synaptic silencing occurs long before the onset of hearing39 and is thus independent of auditory experience. Mapping functional MNTB-LSO connectivity by focal glutamate uncaging demonstrated that the area of the MNTB that provides synaptic input to single LSO neurons (MNTB-LSO areas) shrinks by about 75% during the first postnatal week (Fig. 3b). This decrease accounts for a twofold narrowing of functional MNTB-LSO maps along the tonotopic axis and is completed around P7, days before hearing onset (in rats P12-14).

Figure 3.

Tonotopic refinement of an inhibitory map in the LSO. (a) Before hearing onset, MNTB axons (red) terminate in topographically restricted areas of the LSO. In the 2 weeks following hearing onset, the spread of MNTB axons along the tonotopic axis becomes increasingly restricted. Figure is modified from ref. 32. (b) Before hearing onset, the area in the MNTB that contains neurons that are synaptically connected to single LSO neurons (MNTB input areas) decreases by about 75% (corresponding to a 50% increase in functional tonotopic precision). This indicates that LSO neurons become functionally disconnected from the majority of their presynaptic partners in the MNTB before sound-evoked neuronal activity is present. Figure is modified from ref. 39. (c) Schematic diagram of MNTB-LSO refinement. Before hearing onset, MNTB-LSO connections become silenced (black-dotted axon branches) without being pruned. After hearing onset, pruning of MNTB axons and LSO dendrites occurs, increasing the anatomical tonotopic precision. (d) Schematic illustration of synaptic transmission at MNTB-LSO synapses before (left) and after (right) hearing onset. Figure is based on data from refs. 43,48,53,55. AMPAR, AMPA receptor; GABAR, GABA receptor; Glut, glutamate; Gly, glycine; GlyR, glycine receptor; NMDAR, NMDA receptor; VGCC, voltage-gated calcium channel.

The long delay between pre-hearing synaptic silencing and post-hearing axonal pruning in the MNTB-LSO pathway is unexpected, considering that synaptic weakening in excitatory pathways is very rapidly followed by structural pruning24,40,41. Distinct periods of synapse silencing and axonal pruning may reflect the fact that both processes are guided by distinct sets of mechanisms that are available only at specific developmental stages (Fig. 3c). In support of this idea, synaptic transmission at MNTB-LSO connections differs fundamentally and qualitatively between the periods of silencing and pruning (Fig. 3d). Most noticeably, during the period of synaptic silencing, GABA and glycine, the inhibitory neurotransmitters released from immature MNTB-LSO synapses, are depolarizing instead of hyperpolarizing42,43. This is a result of a high intracellular chloride concentration in immature LSO neurons that leads to a chloride reversal potential that is more positive than the resting membrane potential44,45. In the LSO, depolarizing GABA/glycinergic terminals can trigger action potentials46 and activate voltage-gated calcium channels47. These calcium responses can be locally restricted in aspiny LSO dendrites48, raising the possibility that depolarizing MNTB terminals activate calcium-dependent intracellular cascades involved in changing the strength of GABA or glycinergic synapses49-52 in a synapse-specific manner.

In addition to this depolarizing-hyperpolarizing shift, developing MNTB terminals also undergo a transition in their neurotransmitter phenotype from being primarily GABAergic to being glycinergic43,53. This transition in neurotransmitter phenotype occurs gradually and is largely complete around hearing onset. Because GABA, but not glycine, can induce long-term depression of MNTB-LSO synapse50,54, which in many systems is thought to precede synapse elimination, this transient GABAergic phenotype may be crucial for the functional refinement of the MNTB-LSO pathway.

Perhaps the most intriguing property of immature MNTB neurons is the transient release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate55. Similar to a variety of other neurons that are thought to release neurotransmitters other than glutamate, immature MNTB neurons express vesicular glutamate transporter 3 (refs. 55-57). At MNTB-LSO synapses, glutamate can activate postsynaptic NMDA receptors, the type of glutamate receptor that has been closely linked to synaptic plasticity and circuit refinement58, including the plasticity of inhibitory connections59. Notably, glutamatergic co-transmission is most prevalent during the first postnatal week, the period of synaptic silencing when GABA and glycine are depolarizing and when MNTB-terminals co-release glutamate, a combination that enables the activation of NMDA receptors.

Refinement of excitatory inputs to the LSO and emergence of tonotopic alignment

In contrast with the inhibitory MNTB-LSO pathway, much less is known about the development and refinement of the glutamatergic pathway from the cochlear nucleus to the LSO. Anatomical and physiological studies suggest that excitatory and inhibitory inputs to the LSO mature roughly in parallel8,34,42,60, although the development of cochlear nucleus-LSO topography has not been investigated in any detail. In light of the profound reorganization in the MNTB-LSO pathway, one would expect that the cochlear nucleus-LSO pathway is also refined, so that both pathways remain tonotopically aligned. Alternatively, the cochlear nucleus-LSO pathway could form with final precision and act as a template to which MNTB-LSO connections are topographically matched. Determining which of these two strategies is employed is important for establishing a mechanistic framework for tonotopic matching of binaural inputs in the LSO.

Regardless of the exact strategy that underlies tonotopic alignment, the process of alignment predicts the presence of heterosynaptic interactions between both inputs. Few studies have addressed this important question, although several candidate mechanisms exist in the LSO. For example, a possible route by which GABA/glycinergic MNTB-LSO synapses could influence the strength of cochlear nucleus-LSO synapses is via presynaptic activation of GABAB receptors that are located on glutamatergic cochlear nucleus-LSO synapses43. Although it remains to be shown whether GABA release from MNTB terminals can indeed activate these GABAB receptors, the reverse scenario, heterosynaptic inhibition of MNTB-LSO synapses by cochlear nucleus-LSO synapses, was recently demonstrated61. High-frequency stimulation of glutamatergic cochlear nucleus axons leads to the ‘spillover’ of glutamate to MNTB terminals and activates presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors 2 and 3. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors 2 and 3 decreases the strength of MNTB-LSO synapses via a decrease in the probability of GABA/glycine release. Notably, this heterosynaptic inhibition of MNTB-LSO synapses is most pronounced during the first postnatal week, when silencing of MNTB-LSO synapses is most prominent and when adjustments of functional excitatory-inhibitory maps are expected to be at their peak.

In summary, past research provides a detailed picture of the processes by which the MNTB-LSO pathway becomes refined and has identified a palette of possible synaptic mechanisms that may mediate specific steps in this topographic refinement. The major challenge now is to test whether and to what degree these mechanisms are also involved in refining and aligning bilateral inputs to the LSO in the intact brain.

Subcellular and tonotopic reorganization of inhibition in the MSO

Neurons in the MSO are sensitive to submillisecond differences in the arrival time of synaptic inputs from the two ears. MSO neurons receive converging excitatory inputs from both cochlear nuclei and also receive inhibitory, glycinergic inputs from the MNTB62 (Fig. 1). In animals that rely heavily on ITDs for sound localization (gerbil, cat and chinchilla), glycinergic synapses are located primarily on the soma and apical dendrites of MSO neurons. This subcellular organization is thought to increase the precise timing of inhibition, which is important for processing small ITDs62. The somatic bias of glycinergic synapses is not present before hearing onset but emerges gradually after hearing onset through the selective elimination of synapses located on distal dendrites63 (Fig. 4a). The specific elimination of dendritic MNTB inputs depends on normal auditory experience, as it is impaired by unilateral cochlear ablation or by rearing animals in omnidirectional noise that reduces binaural cues. Omnidirectional noise rearing also impairs ITD tuning of neurons in the dorsal lateral lemniscus, a major target of MSO neurons, indicating that the subcellular refinement of glycinergic synapses in the MSO is highly relevant for normal auditory processing of MSO neurons64. In parallel with the elimination of dendritic glycinergic synapses, there is an increase in the tonotopic precision of MNTB axon terminals by axonal pruning65 (Fig. 4b). Similar to the elimination of dendritic synapses, pruning of MNTB axon branches is impaired by omnidirectional noise rearing. Thus, if increased tonotopic precision of MNTB axon terminals occurs primarily through the elimination of synapses on distal dendrites, then the pruning of tonotopically incorrect axons and the elimination of dendritic synapses may represent two facets of the same refinement process.

Figure 4.

Soma-dendritic and tonotopic refinement of inhibitory inputs to the gerbil MSO. (a) Elimination of dendritic glycinergic synapses occurs after hearing onset and depends on normal hearing experience. Before hearing onset, glycine-positive puncta (pink) are found both on the soma and dendrites (blue) of MSO neurons. In adult animals, glycine labeling is restricted to somatic areas. In animals that received unilateral cochlear ablation (UCA), the density of glycinergic synapses on dendrites is increased. Figure is modified from ref. 63. (b) At hearing onset, MNTB axons (red) in the MSO (blue) spread widely along the dorsoventral tonotopic axis. After one week of hearing (3 weeks old), axonal arbors are pruned, resulting in increased tonotopic precision. Rearing animals in omnidirectional noise (NRA) impairs axonal pruning and tonotopic refinement. Figure is modified from ref.65.

Because many MNTB neurons send axon collaterals to both the LSO and the MSO66, the question arises of whether MNTB axon collaterals in both nuclei are refined by the same rules and synaptic mechanisms. It will be interesting to know whether pruning of MNTB projections to the MSO after hearing onset is preceded by synaptic silencing before hearing onset, as is the case in the LSO39, and whether pruning of MNTB axons in the LSO results in a somatic concentration of MNTB-LSO synapses, as suggested by an apparent concentration of glycine receptors to LSO cell bodies67.

In contrast with the pronounced subcellular reorganization of inhibitory inputs to the MSO, much less, if any, subcellular reorganization seems to occur in the glutamatergic afferent pathways. In mature MSO neurons, axon terminals from each cochlear nucleus terminate on opposing dendritic trees of bipolar MSO neurons. Axons from the ipsilateral cochlear nucleus contact laterally directed dendrites, whereas axons from the contralateral cochlear nucleus contact medially directed dendrites, an organization that optimizes coincidence detection68. This subcellular organization is obvious as soon as developing cochlear nucleus axons invade the MSO and no evidence exists that cochlear nucleus axons transiently contact MSO dendrites on the ‘wrong’ side8,69, unless degeneration of the pathway is induced by neonatal cochlear ablation and associated neuronal death in the VCN70,71. These results suggest that MSO neurons express molecular markers that prevent cochlear nucleus axons from crossing over to the wrong dendritic tree. In the chicken nucleus laminaris (the avian analog of the MSO), one of these guidance molecules is the EphA4 receptor. EphA4 receptors are differentially expressed in the neuropil that receives ipsilateral inputs and disruption of EphA4 signaling increases the number of cochlear nucleus axons that terminate in the inappropriate neuropil72. EphA4 receptor and its ligand, ephrin-B2, may also guide dendritic afferent segregation in the MSO, as both molecules are expressed in the mammalian auditory brainstem, where they are involved in the initial formation of tonotopy73.

Development of MNTB circuitry is largely predetermined

The MNTB is the major source of inhibition for both the MSO and LSO. MNTB neurons receive glutamatergic inputs from globular bushy cells in the contralateral cochlear nucleus, which form a giant synapse, the calyx of Held, onto the soma of MNTB neurons. The calyx of Held provides highly secure synaptic transmission with extreme temporal fidelity and is thought to be important for the precise detection of ITDs and ILDs. A wealth of studies indicate that the major steps in the maturation of anatomical and physiological properties of the calyx of Held and of postsynaptic MNTB neurons occur before hearing onset8,74 and without spontaneous auditory nerve activity75,76. However, spontaneous auditory nerve activity is required for the establishment of a tonotopic gradient in the expression of voltage-gated conductances in MNTB neurons76.

A notable feature of the MNTB is that the vast majority of MNTB neurons are contacted by a single calyx of Held. This one-to-one connectivity is present as soon as calyces form77, in stark contrast with other single-fiber innervation patterns, such as the neuromuscular junction78 or climbing fiber innervation of cerebellar Purkinje79 cells, for which a single-fiber innervation is achieved by the elimination of supernumerous inputs. Therefore, if elimination or competition between calyceal axons for MNTB targets occurs, this competition takes place when growth cones first target and explore MNTB cells and before the formation of the first discernible proto-calyx.

Role of neuronal activity in tonotopic refinement

Two major questions for understanding the mechanisms that govern the tonotopic refinement of auditory brainstem maps are to what degree and how synaptic activity contributes to this reorganization. Tonotopic refinement of auditory brainstem circuits occurs both before and after hearing onset and evidence exists that both spontaneously generated and sound-evoked neuronal activity patterns are important.

Role of spontaneous activity before hearing onset

Spontaneous patterns of neuronal activity, generated endogenously before the onset of sensory experience, can provide an important instructive signal for the refinement of sensory circuits1,31. In the pre-hearing auditory system, spontaneous bursts of spike activity have been described for the auditory nerve and several brainstem nuclei29,30,80,81. These spontaneous action potential bursts originate in the pre-hearing cochlea. Non-neuronal support cells in Kölliker’s organ release ATP, which activates purinergic P2X and P2Y receptors on adjacent inner hair cells (IHCs)82. Activation of ATP receptors on IHCs leads to depolarizations and the generation of bursts of calcium action potentials, glutamate release onto postsynaptic spiral ganglion processes, and bursts of action potentials in the auditory nerve. Notably, ATP release from support cells synchronized the activity of about 5–10 neighboring (tonotopically similar) IHCs, whereas the activity with more distant (tonotopically different) IHCs is uncorrelated. The synchronized discharge of tonotopically similar auditory nerve fibers and central neurons is perfectly suited to act as a signal for the activity-dependent refinement of topographic maps.

Traditionally, the role of spontaneous activity on auditory brainstem development has been addressed by eliminating spontaneous activity with unilateral or bilateral cochlear ablation. However, denervation of the cochlear nucleus before hearing onset induces a number of pathological changes, including pronounced neuronal cell death in the cochlear nucleus and induction of previously unknown auditory pathways6,70,71, which makes it difficult to ascribe ablation-induced effects to the sole absence of spike activity. To circumvent this problem, researchers are now increasingly using congenitally deaf mice with defined hair cell defects83,84. However, the consequences of hereditary deafness in auditory brainstem neurons can differ between mouse strains and different mutations probably affect auditory nerve activity in different ways. It will therefore be necessary to characterize auditory nerve activity patterns in vivo at early neonatal ages, which in small mice is technically difficult. Consequently, although available results are consistent with a role for cochlea-generated spontaneous activity patterns in topographic sharpening before hearing onset, experimental proof will rely on the development of new experimental or genetic animal models with defined changes in the level or patterns of spontaneous activity.

Role of sound-evoked activity

The most commonly used approach to investigate the role of auditory experience on auditory brainstem development is abolishing hearing by deafening. A common finding of these studies is that deafening does not abolish the overall topographic organization of auditory brainstem pathways but decreases tonotopic resolution and precision37,84,85. The magnitude of observed effects varies between pathways and nuclei, which probably also depends on variations in the type of deafening used (cochlear ablation, ototoxic drugs and mutant animals), resolution of analysis (bulk labeling and single-fiber analysis) and species. In addition, deafening in most studies affected both pre-hearing and post-hearing activity, making it difficult to assign the observed effects to impairments in spontaneous versus sound-evoked activity.

Few studies have investigated whether the quality of early auditory experience is important for refining auditory brainstem maps. Rearing gerbils in pulsed broadband noise, a condition that is expected to produce spiking synchronicity across differently tuned auditory nerve fibers, reduces the frequency tuning of neurons in the inferior colliculus86. This result is consistent with the idea that precise frequency tuning may depend on competition-based segregation of inputs that are tuned to different frequencies and that, in a natural environment, are not activated synchronously. Another example comes from the MSO, where the subcellular and tonotopic refinement of inhibitory inputs is impaired after early exposure to continuous omnidirectional noise63,65. These findings raise a number of important questions that wait to be addressed. For example, is auditory-experience dependence a property of only binaural nuclei or is it also a property of monaural pathways? What is the exact extent of the critical period during which auditory experience exerts its effect? Are impairments resulting from abnormal experience permanent or can they be reversed?

Conclusions

Although is has become clear that synaptic reorganization is a major step in normal auditory brainstem development, the extent to which this reorganization contributes to the development of auditory processing and ultimately auditory guided behavior is less clear. Initial attempts to link specific deficits in the organization of inhibitory inputs in the MSO to the animal sound localization performance have so far been unsuccessful87, but more needs to be done before this issue can be resolved. In light of recent results from human studies that auditory learning and experience can induce changes already on the brainstem level88,89 and that specific language impairment or autism disorders frequently are accompanied by deficits in auditory brainstem processing90,91, insight into the mechanisms underlying brainstem plasticity and reorganization will probably have important clinical implications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Goldring for editorial support and B. Cornell for insightful discussions. Our work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the Alfred R. Sloan Foundation and the Pennsylvania Lions Hearing Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggermont JJ. The role of sound in adult and developmental auditory cortical plasticity. Ear Hear. 2008;29:819–829. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181853030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keuroghlian AS, Knudsen EI. Adaptive auditory plasticity in developing and adult animals. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007;82:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang EF, Merzenich MM. Environmental noise retards auditory cortical development. Science. 2003;300:498–502. doi: 10.1126/science.1082163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahmen JC, King AJ. Learning to hear: plasticity of auditory cortical processing. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007;17:456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubel EW, Fritzsch B. Auditory system development: primary auditory neurons and their targets. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;25:51–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurung B, Fritzsch B. Time course of embryonic midbrain and thalamic auditory connection development in mice as revealed by carbocyanine dye tracing. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;479:309–327. doi: 10.1002/cne.20328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandler K, Friauf E. Pre- and postnatal development of efferent connections of the cochlear nucleus in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;328:161–184. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friauf E, Kandler K. Auditory projections to the inferior colliculus of the rat are present by birth. Neurosci. Lett. 1990;120:58–61. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lippe W, Rubel EW. Ontogeny of tonotopic organization of brain stem auditory nuclei in the chicken: implications for development of the place principle. J. Comp. Neurol. 1985;237:273–289. doi: 10.1002/cne.902370211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friauf E. Tonotopic order in the adult and developing auditory system of the rat as shown by c-fos immunocytochemistry. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1992;4:798–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanes DH, Merickel M, Rubel EW. Evidence for an alteration of the tonotopic map in the gerbil cochlea during development. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;279:436–444. doi: 10.1002/cne.902790308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lippe WR, Fuhrmann DS, Yang W, Rubel EW. Aberrant projection induced by otocyst removal maintains normal tonotopic organization in the chick cochlear nucleus. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:962–969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-00962.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tzounopoulos T, Kim Y, Oertel D, Trussell LO. Cell-specific, spike timing-dependent plasticities in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:719–725. doi: 10.1038/nn1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujino K, Oertel D. Bidirectional synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum-like mammalian dorsal cochlear nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:265–270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135345100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Gain adjustment of inhibitory synapses in the auditory system. Biol. Cybern. 2003;89:363–370. doi: 10.1007/s00422-003-0441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molea D, Rubel EW. Timing and topography of nucleus magnocellularis innervation by the cochlear ganglion. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;466:577–591. doi: 10.1002/cne.10896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koundakjian EJ, Appler JL, Goodrich LV. Auditory neurons make stereotyped wiring decisions before maturation of their targets. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14078–14088. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3765-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huffman KJ, Cramer KS. EphA4 misexpression alters tonotopic projections in the auditory brainstem. Dev. Neurobiol. 2007;67:1655–1668. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cramer KS. Eph proteins and the assembly of auditory circuits. Hear. Res. 2005;206:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fariňas I, et al. Spatial shaping of cochlear innervation by temporally regulated neurotrophin expression. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:6170–6180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06170.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson H, Parks TN. Functional synapse elimination in the developing avian cochlear nucleus with simultaneous reduction in cochlear nerve axon branching. J. Neurosci. 1982;2:1736–1743. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-12-01736.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhaveri S, Morest DK. Sequential alterations of neuronal architecture in nucleus magnocellularis of the developing chicken: a Golgi study. Neuroscience. 1982;7:837–853. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu T, Trussell LO. Development and elimination of endbulb synapses in the chick cochlear nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:808–817. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4871-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Y, Harris JA, Rubel EW. Development of spontaneous miniature EPSCs in mouse AVCN neurons during a critical period of afferent-dependent neuron survival. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;97:635–646. doi: 10.1152/jn.00915.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leake PA, Snyder RL, Hradek GT. Postnatal refinement of auditory nerve projections to the cochlear nucleus in cats. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002;448:6–27. doi: 10.1002/cne.10176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snyder RL, Leake PA. Topography of spiral ganglion projections to cochlear nucleus during postnatal development in cats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;384:293–311. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970728)384:2<293::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh EJ, Romand R. Functional development of the cochlea and the cochlear nerve. In: Romand R, editor. Development of Auditory and Vestibular Systems. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1992. pp. 161–220. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones TA, Leake PA, Snyder RL, Stakhovskaya O, Bonham B. Spontaneous discharge patterns in cochlear spiral ganglion cells before the onset of hearing in cats. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;98:1898–1908. doi: 10.1152/jn.00472.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh EJ, McGee J. Rhythmic discharge properties of caudal cochlear nucleus neurons during postnatal development in cats. Hear. Res. 1988;36:233–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stellwagen D, Shatz CJ. An instructive role for retinal waves in the development of retinogeniculate connectivity. Neuron. 2002;33:357–367. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanes DH, Siverls V. Development and specificity of inhibitory terminal arborizations in the central nervous system. J. Neurobiol. 1991;22:837–854. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tollin DJ. The lateral superior olive: a functional role in sound source localization. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:127–143. doi: 10.1177/1073858403252228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanes DH, Rubel EW. The ontogeny of inhibition and excitation in the gerbil lateral superior olive. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:682–700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-02-00682.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanes DH, Song J, Tyson J. Refinement of dendritic arbors along the tonotopic axis of the gerbil lateral superior olive. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1992;67:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90024-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rietzel HJ, Friauf E. Neuron types in the rat lateral superior olive and developmental changes in the complexity of their dendritic arbors. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;390:20–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanes DH, Takacs C. Activity-dependent refinement of inhibitory connections. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1993;5:570–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanes DH, Markowitz S, Bernstein J, Wardlow J. The influence of inhibitory afferents on the development of postsynaptic dendritic arbors. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;321:637–644. doi: 10.1002/cne.903210410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim G, Kandler K. Elimination and strengthening of glycinergic/GABAergic connections during tonotopic map formation. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:282–290. doi: 10.1038/nn1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonini A, Stryker MP. Rapid remodeling of axonal arbors in the visual cortex. Science. 1993;260:1819–1821. doi: 10.1126/science.8511592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colman H, Nabekura J, Lichtman JW. Alterations in synaptic strength preceding axon withdrawal. Science. 1997;275:356–361. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kandler K, Friauf E. Development of glycinergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the auditory brainstem of perinatal rats. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:6890–6904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06890.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kotak VC, Korada S, Schwartz IR, Sanes DH. A developmental shift from GABAergic to glycinergic transmission in the central auditory system. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:4646–4655. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04646.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ehrlich I, Lohrke S, Friauf E. Shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing glycine action in rat auditory neurones is due to age-dependent Cl- regulation. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1999;520:121–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kakazu Y, Akaike N, Komiyama S, Nabekura J. Regulation of intracellular chloride by cotransporters in developing lateral superior olive neurons. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:2843–2851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-02843.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kullmann PH, Kandler K. Glycinergic/GABAergic synapses in the lateral superior olive are excitatory in neonatal C57Bl/6J mice. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2001;131:143–147. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00271-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kullmann PH, Ene FA, Kandler K. Glycinergic and GABAergic calcium responses in the developing lateral superior olive. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;15:1093–1104. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kullmann PH, Kandler K. Dendritic Ca2+ responses in neonatal lateral superior olive neurons elicited by glycinergic/GABAergic synapses and action potentials. Neuroscience. 2008;154:338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luscher B, Keller CA. Regulation of GABAA receptor trafficking, channel activity and functional plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;102:195–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Long-lasting inhibitory synaptic depression is age- and calcium-dependent. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:5820–5826. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05820.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meier J. The enigma of transmitter-selective receptor accumulation at developing inhibitory synapses. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0694-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magnusson AK, Park TJ, Pecka M, Grothe B, Koch U. Retrograde GABA signaling adjusts sound localization by balancing excitation and inhibition in the brainstem. Neuron. 2008;59:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nabekura J, et al. Developmental switch from GABA to glycine release in single central synaptic terminals. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:17–23. doi: 10.1038/nn1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang EH, Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Long-term depression of synaptic inhibition is expressed postsynaptically in the developing auditory system. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1479–1488. doi: 10.1152/jn.00386.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gillespie DC, Kim G, Kandler K. Inhibitory synapses in the developing auditory system are glutamatergic. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:332–338. doi: 10.1038/nn1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blaesse P, Ehrhardt S, Friauf E, Nothwang HG. Developmental pattern of three vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat superior olivary complex. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;320:33–50. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seal RP, Edwards RH. Functional implications of neurotransmitter co-release: glutamate and GABA share the load. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006;6:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kullmann DM, Asztely F, Walker MC. The role of mammalian ionotropic receptors in synaptic plasticity: LTP, LTD and epilepsy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000;57:1551–1561. doi: 10.1007/PL00000640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaiarsa JL, Caillard O, Ben Ari Y. Long-term plasticity at GABAergic and glycinergic synapses: mechanisms and functional significance. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:564–570. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanes DH. The development of synaptic function and integration in the central auditory system. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:2627–2637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02627.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nishimaki T, Jang IS, Ishibashi H, Yamaguchi J, Nabekura J. Reduction of metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated heterosynaptic inhibition of developing MNTB-LSO inhibitory synapses. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26:323–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grothe B. New roles for synaptic inhibition in sound localization. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrn1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kapfer C, Seidl AH, Schweizer H, Grothe B. Experience-dependent refinement of inhibitory inputs to auditory coincidence-detector neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:247–253. doi: 10.1038/nn810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seidl AH, Grothe B. Development of sound localization mechanisms in the mongolian gerbil is shaped by early acoustic experience. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:1028–1036. doi: 10.1152/jn.01143.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Werthat F, Alexandrova O, Grothe B, Koch U. Experience-dependent refinement of the inhibitory axons projecting to the medial superior olive. Dev. Neurobiol. 2008;68:1454–1462. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Banks MI, Smith PH. Intracellular recordings from neurobiotin-labeled cells in brain slices of the rat medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:2819–2837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02819.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friauf E, Hammerschmidt B, Kirsch J. Development of adult-type inhibitory glycine receptors in the central auditory system of rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;385:117–134. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970818)385:1<117::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agmon-Snir H, Carr CE, Rinzel J. The role of dendrites in auditory coincidence detection. Nature. 1998;393:268–272. doi: 10.1038/30505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kil J, Kageyama GH, Semple MN, Kitzes LM. Development of ventral cochlear nucleus projections to the superior olivary complex in gerbil. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;353:317–340. doi: 10.1002/cne.903530302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kitzes LM, Kageyama GH, Semple MN, Kil J. Development of ectopic projections from the ventral cochlear nucleus to the superior olivary complex induced by neonatal ablation of the contralateral cochlea. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;353:341–363. doi: 10.1002/cne.903530303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Russell FA, Moore DR. Afferent reorganization within the superior olivary complex of the gerbil: development and induction by neonatal, unilateral cochlear removal. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;352:607–625. doi: 10.1002/cne.903520409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cramer KS, Bermingham-McDonogh O, Krull CE, Rubel EW. EphA4 signaling promotes axon segregation in the developing auditory system. Dev. Biol. 2004;269:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miko IJ, Nakamura PA, Henkemeyer M, Cramer KS. Auditory brainstem neural activation patterns are altered in EphA4- and ephrin-B2-deficient mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;505:669–681. doi: 10.1002/cne.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taschenberger H, Leao RM, Rowland KC, Spirou GA, von Gersdorff H. Optimizing synaptic architecture and efficiency for high-frequency transmission. Neuron. 2002;36:1127–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Youssoufian M, Oleskevich S, Walmsley B. Development of a robust central auditory synapse in congenital deafness. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3168–3180. doi: 10.1152/jn.00342.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leao RN, et al. Topographic organization in the auditory brainstem of juvenile mice is disrupted in congenital deafness. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2006;571:563–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoffpauir BK, Grimes JL, Mathers PH, Spirou GA. Synaptogenesis of the calyx of Held: rapid onset of function and one-to-one morphological innervation. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:5511–5523. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5525-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lichtman JW, Colman H. Synapse elimination and indelible memory. Neuron. 2000;25:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hashimoto K, Kano M. Postnatal development and synapse elimination of climbing fiber to Purkinje cell projection in the cerebellum. Neurosci. Res. 2005;53:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lippe WR. Rhythmic spontaneous activity in the developing avian auditory system. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:1486–1495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01486.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Synaptically evoked prolonged depolarizations in the developing auditory system. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1611–1620. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.4.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tritsch NX, Yi E, Gale JE, Glowatzki E, Bergles DE. The origin of spontaneous activity in the developing auditory system. Nature. 2007;450:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Walmsley B, Berntson A, Leao RN, Fyffe RE. Activity-dependent regulation of synaptic strength and neuronal excitability in central auditory pathways. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2006;572:313–321. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.104851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cao XJ, McGinley MJ, Oertel D. Connections and synaptic function in the posteroventral cochlear nucleus of deaf jerker mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008;510:297–308. doi: 10.1002/cne.21788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leake PA, Hradek GT, Chair L, Snyder RL. Neonatal deafness results in degraded topographic specificity of auditory nerve projections to the cochlear nucleus in cats. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006;497:13–31. doi: 10.1002/cne.20968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sanes DH, Constantine-Paton M. Altered activity patterns during development reduce neural tuning. Science. 1983;221:1183–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.6612332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maier JK, Kindermann T, Grothe B, Klump GM. Effects of omni-directional noise-exposure during hearing onset and age on auditory spatial resolution in the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus)—a behavioral approach. Brain Res. 2008;1220:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Russo NM, Nicol TG, Zecker SG, Hayes EA, Kraus N. Auditory training improves neural timing in the human brainstem. Behav. Brain Res. 2005;156:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wong PC, Skoe E, Russo NM, Dees T, Kraus N. Musical experience shapes human brainstem encoding of linguistic pitch patterns. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:420–422. doi: 10.1038/nn1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wible B, Nicol T, Kraus N. Atypical brainstem representation of onset and formant structure of speech sounds in children with language-based learning problems. Biol. Psychol. 2004;67:299–317. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Russo NM, et al. Deficient brainstem encoding of pitch in children with autism spectrum disorders. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008;119:1720–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.01.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]